Chris Hedges's Blog, page 377

December 29, 2018

Gene-Edit to Make Babies Smarter, Faster, Taller? Most Americans Say No.

WASHINGTON—Most Americans say it would be OK to use gene-editing technology to create babies protected against a variety of diseases—but a new poll finds they’d draw the line at changing DNA so children are born smarter, faster or taller.

A month after startling claims of the births of the world’s first gene-edited babies in China, the poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research finds people are torn between the medical promise of a technology powerful enough to alter human heredity and concerns over whether it will be used ethically.

Jaron Keener, a 31-year-old exhibit designer at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History, said he’s opposed to “rich people being able to create designer babies.”

But like the majority of Americans, Keener would support gene editing in embryos to prevent incurable diseases. His mother has lupus, an inflammatory disease that may have both environmental and genetic triggers.

Lupus has been “a looming presence my entire life. I’ve been around somebody with a chronic illness and I’ve seen the toll that has taken, not just on her life, but the life of my family,” he said.

Gene editing is like a biological cut-and-paste program, letting scientists snip out a section of DNA to delete, replace or repair a gene. Altering adult cells would affect only the patient being treated.

But editing genes in eggs, sperm or embryos would alter the resulting child in ways that can be passed to future generations — a step with such profound implications that international science guidelines say it shouldn’t be tested in human pregnancies until more lab-based research determines it’s safe to try.

The AP-NORC poll shows about 7 in 10 Americans favor one day using gene-editing technology to prevent an incurable or fatal disease a child otherwise would inherit, such as cystic fibrosis or Huntington’s disease.

Roughly two-thirds of Americans also favor using gene editing to prevent a child from inheriting a non-fatal condition such as blindness, and even to reduce the risk of diseases that might develop later in life, such as cancers.

Side effects are possible, such as a gene-editing attempt that accidentally alters the wrong DNA spot, and the poll finds 85 percent think that risk is at least somewhat likely.

But about 7 in 10 Americans oppose using gene editing to alter capabilities such as intelligence or athletic talent, and to alter physical features such as eye color or height.

The poll highlights that if gene editing of embryos ever moves into fertility clinics, there will be some hard choices about what non-fatal disorders should qualify, said Columbia University bioethicist Dr. Robert Klitzman. What if scientists could pinpoint genes involved with depression or autism or obesity — would they be OK to edit?

“It’s one thing to look at the extremes of fatal diseases versus cosmetic things, but in the middle are going to be these very different issues,” Klitzman said.

That reported gene editing in China was an attempt to create babies resistant to HIV infection, a target that many scientists in the U.S. and elsewhere decried because there are effective ways to prevent the AIDS virus.

The poll shows most people think it is at least somewhat likely that gene editing could wipe out certain inherited diseases and lead to other medical advances.

Yet despite the medical enthusiasm, more Americans oppose than favor government funding for testing on human embryos to develop gene-editing technology — 48 percent to 26 percent. About another quarter of the population takes no stand.

Without that research, how could gene editing ever become a choice for families hoping to avoid a disease?

“That’s a good question,” said Keener, the Pittsburgh museum worker, who opposes such funding for fear that research would lead to designer babies rather than fighting disease.

“If there would be a way to narrow the scope of research, I would be OK with government funding,” he said. “I just don’t have a lot of confidence people wouldn’t use it for their own gain.”

Indeed, the poll uncovers a lack of trust in science: About a third think this kind of gene editing will be used before it’s adequately tested, as many scientists say happened in China. Nearly 9 in 10 people think the technology will be used for unethical reasons, including 52 percent who say this is very likely to happen.

And roughly three-quarters of Americans say gene editing probably wouldn’t be affordable for the average person — raising the specter of certain genetic diseases becoming a problem only for the poor.

“People appear to realize there’s a major question of how we should oversee and monitor use of this technology if and when it becomes available,” said Columbia’s Klitzman. “What is safe enough? And who will determine that? The government? Or clinicians who say, ‘Look, we did it in Country X a few times and it seems to be effective.'”

___

The AP-NORC poll of 1,067 adults was conducted Dec. 13-16 using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 4.1 percentage points.

Respondents were first selected randomly using address-based sampling methods, and later interviewed online or by phone.

___

AP reporters Carla K. Johnson in Seattle and Hannah Fingerhut in Washington contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press Health & Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Immigrant Child Reunited With Family in El Salvador, but Life Is Different Now

Christmas wasn’t going to be much this year at the Maldonados’ tiny home in eastern El Salvador. Then 6-year-old Wilder arrived, lugging a duffel bag fat with the brightly colored remnants of his brief life in the United States — time he’d spent separated from his father by immigration authorities.

Suddenly, the two shabby rooms with dirt floors and drab adobe walls turned festive. As a pot of chicken stew simmered on a wood-burning stove, a group of barefoot children rummaged with glee through the big black bag, pulling out treasures.

Two-year-old Kevien claimed the Spider-Man pajamas and the talking Spider-Man mask that said things like, “Look out, it’s web-slinging time!” Darwin, a neighbor’s kid, posed in a pair of red Spider-Man glasses with silvery-white webs and blinking lights on the frames.

Yohana, 14 and wispy like a ballerina, picked up a glossy soccer ball that had “USA,” emblazoned on one side and called Darwin outside to play. Meanwhile, the baby, MiLeidi, 8 months old, squealed in delight at a stuffed Olaf, the snowman from “Frozen,” that was bigger than she was.

The only kid who didn’t seem to care much about the contents of the duffel bag was Wilder. He sat by himself on the only bed in the house, apart from the commotion, engrossed in games on his mother’s old cellphone. Kevien offered Wilder the talking mask, trying to entice him to come play. But, without looking up from the cellphone, Wilder shook his head and turned away.

The toys in the duffel bag were all he had left from a seven-month journey to the U.S. with his father, Hilario Maldonado, that had taken him a world away from El Salvador and his family’s impoverished existence, to a place with television sets and hot showers, where he’d slept in a bunk bed and ate as much pizza as he wanted. They’d traveled there in a succession of trucks so crowded with other immigrants that he’d nearly suffocated, and they had reached their goal only to be separated for months in a uniquely American limbo. When he and his father were finally reunited, it was only to be put on a government airplane and flown back to El Salvador, undoing an effort that cost months of hardship and thousands of dollars.

Wilder is one of the nearly 3,000 migrant children who were affected this year by the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy. His separation from his father first became public when he appeared alone in court in late November wearing a hat with googly eyes and a red yarn mohawk. Under the unprecedented crackdown, immigration officials were required to prosecute everyone they caught illegally crossing the border and to seize any children they brought with them.

Wilder’s father, a struggling 38-year-old farmer, was not aware of the policy when he set out from El Salvador, seeking decent work for himself and a brighter future for his son. He surrendered himself and his son to U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers as soon as he crossed the Rio Grande into Texas. But after five days in CBP custody, agents took Wilder away from Maldonado, sending the boy to a temporary foster home in San Antonio and his father to a detention center about an hour’s drive away.

The zero-tolerance crackdown ended — at least officially — a short time later, when a storm of international outrage forced the administration to rescind it. A federal judge ordered authorities to reunite all the affected children with their families, an effort that took months and tens of millions of dollars because immigration officials hadn’t kept complete records of which children belonged to which adults. Wilder, pudgy, with a buzz cut and missing most of his front teeth, was one of the last cases to be resolved.

Dec. 21 was Wilder’s first morning back home. And his mind seemed somewhere else.

When asked how he was doing, Wilder answered in English, without taking his eyes off the phone. “I’m fine.”

He didn’t respond at all when asked whether he was happy to be back. His mother, Maria Elida Cabrera, nudged him. “Wilder, you’re happy to be home with me, right?” she said in Spanish.

Wilder looked up for a couple of seconds and forced a smile. “Yes, I’m happy,” he said, again in English, then returned to his game.

Cabrera, 35, her straight black hair in a messy ponytail, walked out the backdoor of the house and lowered her voice so that Wilder couldn’t hear her. “This has to be hard for him,” she said. “It’s been hard for all of us.”

Back with his family, Wilder didn’t want to talk much about his experiences, not that he’s old enough to make sense of them. Except for the immigration officials who separated him from his dad, he’d been a victim of a lot of people’s good intentions. There was his father’s desperate attempt to lift his family out of misery; a Texas foster family’s eagerness to provide him a comfortable, and comforting, life; and a federal court’s decision to end zero tolerance and send Wilder back to his family in El Salvador.

For now, the best insight into what might be going on in Wilder’s young mind comes from the adults who shared his ordeal. They sound sad and whiplashed.

“I don’t know what it was about him, but it was hard to let him go,” said Erica Gallegos, the San Antonio woman who took care of Wilder during his time in the U.S. She cried for most of a 45-minute phone call. “In a very short time, he became a part of the family.”

To Cabrera, Wilder’s mother, his time away seemed an eternity. He had changed in so many ways that she described feeling dizzy just looking at him. None of his old clothes fit because he’d been much thinner when he left. And his smile was filled with gaps from all the baby teeth he’d lost. He’d also ridden on an airplane and a ferry, swam in the Gulf of Mexico, let a barber cut his hair, gotten vaccinations, had his first crush on a girl, gone to a movie theater, and learned to tie his shoes, write his name and ride a bike. His vocabulary had grown. He can count to 20 in English. And he doesn’t bark commands at her anymore, she said. He now says “please” and “thank you.”

“There are things he tells me, and I don’t know what he’s talking about,” Cabrera said. “What’s a Grinch?”

Migrating to the U.S. was not new to Wilder’s father. Maldonado had lived in the U.S. through the late 1990s and early 2000s, first immigrating illegally, then gaining temporary protected status in 2001. El Salvador had suffered a series of deadly earthquakes and the Bush administration agreed to let 150,000 Salvadoran immigrants stay and work in the U.S., hoping the money they’d send back to their families would help the Central American country recover.

Maldonado was a single man back then. He worked restaurant and construction jobs up and down the East Coast, from Tampa, Florida, to Long Island in New York, to help take care of his mother in El Salvador. But in 2003, Maldonado said, he returned home when his mother fell ill, using some of the money he’d made to get her medical attention. Shortly afterward, he met Cabrera — who is related to the wife of one of his brothers — started a family, bought a few head of cattle to breed and sell, and built their simple home with his own hands. It’s located on a patch of his wife’s family’s property outside a quaint Salvadoran town called Lislique.

“My intention was to stay in El Salvador,” Maldonado said. “I only left because I started to have problems.”

Cabrera and Maldonado said the cattle business began failing about four years ago. Maldonado had attempted an expansion, borrowing several thousand dollars to grow his herd. But the country’s violent street gangs began moving into Lislique and demanding a cut of Maldonado’s profits. Cabrera said her husband started looking for odd jobs to supplement his income to pay both his debts and the money the gangs demanded.

Each month, there was less money to cover the family’s needs, Cabrera said. And when Maldonado told the gangs he couldn’t afford to pay them anymore, she said, they beat him up and threatened to kill him.

In May, Cabrera said, her husband decided to gamble one more time. He borrowed $5,500 to pay smugglers, known as coyotes, to take him to the U.S. to seek asylum. The plan was to earn enough money to provide for her and the kids left behind, and then, once his status was secure, bring them to the U.S., too.

The coyotes, she said, warned Maldonado that crossing the border wasn’t as easy as it was the last time he migrated. Rather than sneaking into the country, they told him he should turn himself in immediately to border authorities. And they suggested that he bring along one of his kids because he’d spend less time in detention if he had a child with him.

“I didn’t want to let Wilder go,” Cabrera said. “But Hilario said it was the only way. He promised he would take good care of Wilder. He said Wilder would have opportunities that don’t exist here in El Salvador.”

Maldonado said the trip across Central America and Mexico, mostly in the back of pickup trucks and packed tractor-trailers that were not equipped for human cargo, was grueling for him and nearly fatal for Wilder. “I was trying to give him a better life,” Maldonado said of his son, “and he almost died, twice.”

One of the trailers, Maldonado said, was so overcrowded and tightly sealed that Wilder passed out. He scrambled to find an opening in the trailer’s hull, he said, shoving aside the men standing next to it and pushing Wilder’s mouth and nose against the hole until he opened his eyes.

On another leg of the trip, Wilder fainted again as he and his father rode in the back of a pickup truck in a driving rainstorm. When asked why he would take such risks with his son, Maldonado said: “I was desperate. I thought if I didn’t get out of El Salvador, my children would starve or become orphans.”

Maldonado said he thought the hardest part of the journey was over when he and Wilder arrived at the U.S. border on May 31. Then they ran head-on into the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy.

“The agents came to me and grabbed Wilder out of my arms,” said Maldonado, a brawny man with a square jaw and metal caps on his front teeth. “He was screaming for me: ‘Papa, papa!’ But I couldn’t do anything. I couldn’t run after him. I remember I just watched as they took him. I felt like my heart was going to stop.”

A few days later, the federal government placed Wilder in foster care with the Gallegos family in San Antonio. Erica Gallegos said there were four other foster children in her house during much of the time Wilder was there. One of them was a 5-year-old Central American boy who had also been separated from his parent.

Gallegos said the two separated boys slept in the same room, Wilder on the top bunk.

Wilder, confused and tired, didn’t speak much his first couple of days in her home, Gallegos said. She said she gave him his space, engaging when he wanted to do so and leaving him alone when he didn’t. By the end of the first week, however, she said she managed to win him over by making it clear that he hadn’t been taken away from his family for good. She was only taking care of him until his family was reunited.

“I told him he could call me tía,” Gallegos said, the Spanish word for aunt. She started to cry and sniffle, “I wanted him to feel at home, but I didn’t want him to think I was trying to be his mom.”

From then on, she said, Wilder settled happily into the Gallegos clan; mom, dad and four children, including three who are adults with families of their own. And the family warmed to him. Erica Gallegos enrolled him in first grade and took him to church on Sundays. They had regular pizza and movie nights. She took him home to visit her parents, in the border town of Del Rio. And Wilder joined the family on a beach vacation to Corpus Christi, where he ate s’mores, watched dolphins swim alongside a ferry and marveled at the size of the sea.

Unlike other children she’s cared for, Gallegos said Wilder seemed to crave rules and routine. She said she taught him once how to fold his clothes and put away his shoes and rarely had to remind him again. She said he made his own bed and asked her to inspect it to make sure he’d done it right. And at night, she said, Wilder wouldn’t fall asleep until she said prayers with him.

Gallegos said Wilder enjoyed going with her 13-year-old daughter to baseball and volleyball games. In fact, she said, he’d go with her just about anywhere. “He loved my daughter,” she said, laughing. “He would always stare at her. One time he asked my husband if she could be his girlfriend.”

Other than Spider-Man and pepperoni pizza, Gallegos said that Wilder’s favorite thing was a long, hot shower.

“Do you want me to tell you how long his showers were?” she said. “Thirty minutes. I’d go in to get him, and the room would be hot and steamy.”

Gallegos started to sniffle again. “I didn’t ever want him to go. I remember telling the social worker to let me call his mom and ask her to let me take care of him. My husband would tell me, ‘Remember, he’s not ours.’”

At the same time, Wilder’s family was in crisis. Maldonado was stuck in detention. He had failed to pass his credible fear interview, the first crucial step in the asylum process in which an officer affirms that an immigrant has a justifiable fear of harm in his home country. And it would be months before he’d get a hearing before a judge. Meanwhile, back in El Salvador, Cabrera struggled on her own to care for their other three children.

Kevien, the 2-year-old, developed parasites in October. He was vomiting, had diarrhea and, Cabrera said, his abdomen swelled like a basketball. She had no money for food and medicine, until an immigrant advocacy organization, established to help families affected by zero tolerance, learned about Cabrera’s troubles and sent money. “Without that help, who knows what would have happened,” Cabrera said. “I don’t even want to think about it.”

By December, Maldonado was tired of fighting. An immigration judge had ruled against his asylum petition, and while he could have appealed, that would have kept him in detention several more weeks. He felt the odds of winning asylum were against him, he said, and his family was falling apart. He agreed to plead guilty to illegally entering the country and be deported. He also asked to take Wilder home with him.

This time, the choice was Wilder’s. When authorities physically separated him from his father, they separated his asylum petition as well. Therefore it was up to him, not his father, to decide whether he would give up the claim and go home. Wilder initially appeared in an immigration court without a lawyer. Afterward, his father’s attorney, Thelma O. Garcia, stepped in to represent him. A transcript of the interview between Wilder and Garcia suggests that the gravity of the decision was lost on him.

Attorney: “Hello, Wilder, do you wish to return to your home?”

Wilder: “Yes.”

Attorney: “Do you understand what I’m asking you?”

Wilder: “Yes.”

Attorney: “Do you want to return to court?”

Wilder: “No.”

Attorney: “Do you want to return with your dad, and your mom and the rest of your family?”

Wilder: “Yes, I want to return to my family and see them.”

Attorney: “OK, we are going to help you return with them very soon.”

Wilder: “Spider-Man is my favorite superhero.”

Still, the statement was sufficient for an immigration judge to order that Wilder be reunited with his father and sent back to El Salvador.

Gallegos said that when Wilder realized he was going to be sent home, he began to withdraw again. She said there’s a Christian song they used to sing on their way to school every morning called “Tuyo Soy,” Spanish for “I Am Yours.” But when she put it on one morning, as his departure day approached, she said, Wilder began sobbing.

“I don’t want to go,” Gallegos said he told her. “I don’t want to leave you. I’m going to miss you so much.”

She said she tried to reassure Wilder that things would be OK, burying her own fears. “He had everything he wanted here,” she said, “and he knew that when he went home, he wasn’t going to have that.”

Before Wilder left, Gallegos and her husband rented “Rambo” and ordered pizza. They woke him before dawn and brought him downstairs to get dressed so that he didn’t disturb his bunkmate. Wilder noticed that Gallegos had packed all his things in a big black duffel bag and asked, “I’m not going to school today?”

“No, you’re going back to your family today,” she answered.

His face went blank, she said. And he stopped talking, barely saying a word throughout breakfast and the car ride to meet his social worker. “He was silent,” Gallegos said of Wilder. “I tried not to cry because I didn’t want him to feel bad.”

When he got out of the car, Wilder wrapped his arms around Gallegos’ waist. In the six months they had been together, she said she’d watched him grow from a size 4 to a size 8 and lose most of his baby teeth. She cried, too, as he walked away.

Wilder was reunited with his father at the airport in Laredo, Texas. They were loaded onto a government plane filled with about 100 other Salvadoran deportees. They landed in El Salvador before lunch. Wilder’s size was not the only thing that distinguished him from the rest of the bunch. The men, including Wilder’s dad, wore tattered T-shirts. But Wilder arrived dressed in black suede Timberlands, a red flannel shirt, a hat with Spider-Man eyes and a frown.

There was another 6-year-old boy on the flight with his mother. They had been separated from each other in September, months after a judge ordered the government to stop the practice, and were reunited that morning. The boy, named Esteven, was chattering away with his mom, as if filling her in on all she’d missed. But Maldonado said Wilder barely spoke to him as officials registered their return and advised them of the government programs available to provide assistance.

His face finally lit up when he saw his mother. She cried as he rushed into her arms. Cabrera said that Wilder told her he was glad to see her, telling her: “Mama, when I was away, I didn’t know when I’d ever see you again. I missed you, Mama.’”

But by the time they had gotten home, Wilder had shut down again. And it was Cabrera trying to win him over. He told her he had changed his name to Peter Parker, but she didn’t know that was Spider-Man’s alter ego. He wanted to watch television, but theirs had died. The tortillas weren’t prepared to Wilder’s liking, so he was feeding his to the cat. He wanted to show her that he could ride a bicycle. Cabrera said with her husband out of work and $5,500 in debt, a new bike was far beyond their means.

Wilder, she said, has told her he has a plan.

“He told me that when he gets older, he wants to go to the United States to work,” she said. “He says he’ll get a good job and send money to take care of me.”

Women in Military, Female Veterans Turning Away From GOP

WASHINGTON—It had been months since retired Lt. Cmdr. Michele Fitzpatrick paid attention to news coverage. She was turned off by President Donald Trump’s tweetstorms and attacks on critics such as the late Republican Sen. John McCain, a war hero. But as the November midterm elections approached, she fired up her laptop.

A member of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy’s Class of 1980, the first to include women, Fitzpatrick began researching candidates and poring over issues. On Election Day, she voted without hesitation: all Democrat.

“I just don’t think what’s happening now is helpful,” Fitzpatrick, of Groton, Connecticut, said in a telephone interview, pointing to the negative discourse in Washington. “It’s almost like watching kids and bullies on the playground instead of people actually doing something about helping this country to survive and to thrive.”

That’s hardly a startling view from a Democrat these days. But from a military vet?

Long seen as a bastion of support for Republicans, the face of the U.S. military and its veterans is changing — and perhaps too is their political bent.

Veterans by and large did vote for GOP candidates on Nov. 6, affirming Trump’s frequent claim that they stand among his strongest backers. But more women are joining the military, and they are bucking the pattern, according to data from AP VoteCast.

The 60-year-old Fitzpatrick recalls suppressing her opinions as a young “hardcore Democrat” in an overwhelmingly Republican military but finding other ways to promote change, such as supporting other female cadets.

Now, women in the military are helping elect new Democratic lawmakers and spur discussion on once little-mentioned topics such as sexual harassment and women in combat roles. As political candidates, female veterans also had a breakout performance in the midterms, sometimes campaigning as a foil to Trump: empathetic and competent on issues such as health care while also trustworthy on military and defense, typically a GOP strength.

“I see this as a beginning edge of a larger movement,” said Jeremy Teigen, professor of political science at Ramapo College and author of “Why Veterans Run: Military Service in American Presidential Elections, 1789-2016.”

Both current and former female service members were more likely to vote in the 2018 midterm elections for Democrats than Republicans, 60 percent to 36 percent, according to the data from VoteCast. Men with military backgrounds voted Republican by roughly the same margin, 58 percent to 39 percent.

A record number of female veterans — four — were elected to the House, all Democrats. Three won in political swing districts, helping give the party control of the chamber next year.

Democratic Rep.-elect Chrissy Houlahan, a former Air Force captain, said she was motivated to run after organizing a bus trip last year to the Women’s March in Washington. She felt her election would serve as a repudiation of Trump, but she avoided sharp rhetoric in favor of a message of service to country and getting things done.

She recalled Pennsylvania voters telling her they were exhausted by gridlock and partisan attacks and “would like our nation and our democracy and our values to stabilize to what we can recognize.”

All told, 55 percent of voters who had served in the military backed Republican candidates in the elections, compared to 42 percent who supported Democrats, according to VoteCast data.

Trump frequently embraces the U.S. military and veterans in speeches, referring to “my military,” though he has also insulted war heroes such as McCain and military families who criticize him. “I think the vets, maybe more than anybody else, appreciate what we are doing for them,” Trump said last month.

Not the female veterans, though. Their margin of support for Democrats was comparable to that of women overall, according to VoteCast data.

AP VoteCast is a nationwide survey of more than 115,000 midterm voters — including more than 4,000 current and former service members — conducted for The Associated Press by NORC at the University of Chicago.

Laura Cavallaro, 35, who served on active duty in the Marine Corps from 2001 to 2005 and on inactive duty until 2009, says she’s never voted but thinks she will in 2020. A recent graduate of Rhode Island College, she said she believes Trump has kept his promises about helping the economy and creating jobs. At the same time, “Who knows if he’s going to say something to the wrong person and start another war?” she said. That’s particularly concerning for military veterans who know what’s at stake in combat.

When Cavallaro joined the military, she considered herself a Republican because her parents were. Now, she sees herself more as an independent, saying she’s pro-gun rights and pro-gay rights.

“I think being in the military kind of opened my eyes to a lot more things,” she said. “If I had stayed in Rhode Island, I wouldn’t have met so many different personalities and people with other political views.”

In 2016, the Defense Department lifted all restrictions on the roles women can perform in the military, spurring broader debate about combat missions and even whether women should be eligible for the draft.

Currently, there are more than 20 million veterans of the U.S. armed forces, about 10 percent of them female, the fastest growing subgroup. In the U.S. military forces, 16.6 percent of those enlisted are women, up from about 2 percent in 1973.

Women now make up 20 percent of the Air Force, 19 percent of the Navy, 15 percent of the Army and 8.6 percent of the Marines, according to Defense Department figures. In the Coast Guard, a division of the Department of Homeland Security, women make up 22 percent of the officers and 13 percent of those enlisted. The Coast Guard Academy, where Fitzpatrick was among the first women to attend in 1976, enrolled a class this year that is 40 percent female, a new high.

Teigen, who studies military voting, said that in the context of the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment, female veterans running for office provided a contrast for voters, “someone who was willing to volunteer to take time out of their youth to serve their country and stand up for others,” compared to Trump, a New York billionaire with five wartime draft deferments and a fraught history with women. Of the military veterans who ran for the House, 12 were women, the highest number ever.

Houlahan will serve her first House term starting in January, along with former Navy pilot Mikie Sherrill, D-N.J., and Navy veteran Elaine Luria, D-Va., who defeated another veteran, Republican Rep. Scott Taylor, a former Navy SEAL. The women prevailed in tight races by tying their opponents to Trump and the GOP congressional majority while pledging to work on both sides of the aisle. All had stories about being among the only women working among men and used their platforms to speak out about abuses in the military.

Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, a frequent Trump critic, also won re-election. She is a member of her state’s National Guard.

In all, seven female veterans will serve in the next Congress, up from four. The veterans in the House will join Sens. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., a former U.S. Army helicopter pilot, and Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, a combat veteran in the Iowa Army National Guard. Rep. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., a retired Air Force colonel, lost her Senate bid but was later appointed by Arizona’s governor to replace Sen. Jon Kyl in the seat that belonged to McCain.

“I sure hope I get to make history,” Houlahan said cautiously, when asked about her candidacy and the influence female veterans could have on Washington. “That would be amazing. And I would be happy to serve everybody, not just the women and the Democrats.”

___

McDermott reported from Providence, Rhode Island. AP writers Lolita C. Baldor, Emily Swanson and Hannah Fingerhut in Washington contributed to this report.

Amid Shutdown, Trump Freezes Pay of 2 Million Federal Workers

With hundreds of thousands of federal employees currently furloughed or working without pay due to the ongoing government shutdown, President Donald Trump delivered another blow to struggling workers on Friday by signing an executive order that will freeze the pay of around two million public employees in 2019.

“This is just pouring salt into the wound,” declared Tony Reardon, president of the National Treasury Employees Union, which represents around 100,000 federal workers. “It is shocking that federal employees are taking yet another financial hit. As if missed paychecks and working without pay were not enough, now they have been told that they don’t even deserve a modest pay increase.”

— Chris Lu (@ChrisLu44) December 29, 2018

Furlough 400,000 federal workers

Require another 400,000 to work without pay

Freeze pay for entire federal civilian workforce

Justify pay freeze on “our nation’s fiscal situation” (which was caused by massive tax cuts)

Lie to troops about the military pay raise https://t.co/k9Htx7auO0

First the shutdown, now this. Adding insult to injury for a federal workforce that is already being held hostage by this President. https://t.co/jBnpTI0NuZ

— Mark Warner (@MarkWarner) December 29, 2018

Trump’s executive order—which largely flew under the radar of national news coverage—makes official his announcement earlier this year that he would cancel a scheduled 2.1 percent pay raise for 1.8 million non-military federal workers.

As justification for the widely denounced move, Trump cited the need to “put our nation on a fiscally sustainable course.”

The president’s sudden concern for the budget deficit came just months after he signed into law $1.5 trillion in tax cuts, which have disproportionately flowed to wealthy Americans and large corporations.

“President Trump pushed through a tax scam that gave unprecedented handouts to billionaires and corporations—but believes it’s too expensive to pay hardworking federal workers a reasonable wage,” wrote Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) following Trump’s August announcement.

The president’s move to freeze the pay of millions of federal workers comes as hundreds of thousands of public employees and government contractors are increasingly worried about being able to make rent and pay their bills, as the partial shutdown heads into January with no agreement in sight.

“We’re sort of being held hostage in the middle, and we have families and obligations,” Dena Ivey, a furloughed probate specialist in the Anchorage office of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, told the New York Times on Friday. “I don’t know if I’m going to be able to make rent. I’m basically living on credit now.”

The Trump administration sparked outrage on Thursday by suggesting that federal workers could do odd jobs for their landlords such as “painting” or “carpentry” to help cover rent as the shutdown continues.

As Vox reported on Thursday, while many federal workers could receive back pay after the government is reopened, thousands of government contractors aren’t “going to be paid at all.”

“As many as 2,000 subcontractors in federal buildings including janitors, security guards, and cafeteria servers are not only experiencing a sharp break in their work schedules, they also won’t be compensated for this pause,” Vox noted. “Government employees typically receive back pay after the shutdown is over, but contractors are paid directly by companies that can’t bill the government for services when it’s shut down. Because these companies won’t get paid, they, in turn, aren’t able to pay their workers.”

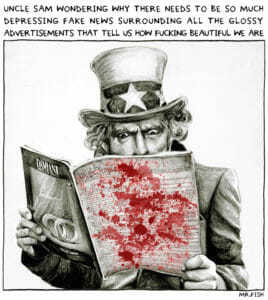

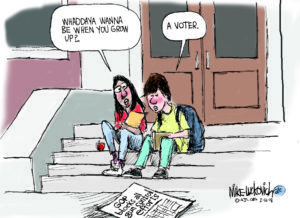

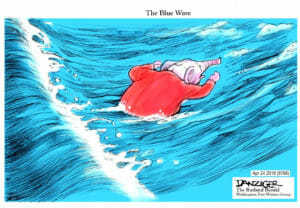

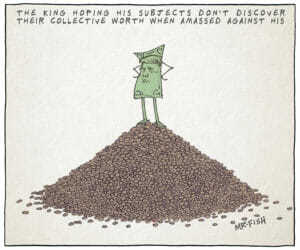

Truthdig’s Top 10 Cartoons of 2018

From a zero-tolerance immigration policy to “zero collusion” claims, 2018 teemed with the Trump administration’s never-ending turmoil and near daily scandals. With such a chaotic administration, it takes the satirical stylings of Mr. Fish, Mark Fiore, Mike Luckovich and Jeff Danziger to help make sense of it all. Take a look at 2018’s top 10 cartoons—and be prepared to smile through the pain until 2020.

10. The Customer is Always Right by Mr.Fish

9. Gina Haspel by Jeff Danziger

8. And This Little Piggy Went to Market by Mr. Fish

7. When I Grow Up by Mike Luckovich

6. Statue of… by Mike Luckovich

5. Blue Wave by Jeff Danziger

4. Power Drain by Mr. Fish

3. Justice is Blind Drunk by Mark Fiore

2. The Buck Stops Here by Mr. Fish

1. The Really Dangerous Caravan by Mark Fiore

December 28, 2018

Democrats Won’t Seat GOP Candidate in Contested Race, House Leader Says

RALEIGH, N.C.—The dissolution of North Carolina’s elections board Friday injected further uncertainty into a still-undecided congressional race as a U.S. House Democratic leader rejected the idea of filling the seat until an investigation of ballot fraud allegations is complete.

Gov. Roy Cooper was met with Republican resistance after announcing he would appoint an interim Board of Elections after a three-judge state court panel ruled Thursday that the current board should disband at noon Friday. The Democrat’s move would fill the gap — and allow the board to proceed with a Jan. 11 evidentiary hearing about the 9th District congressional race — until a new law governing the statewide elections panel can take effect Jan. 31.

Amid the turmoil, incoming U.S. House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer issued a statement saying House Democrats won’t allow Republican Mark Harris to be sworn in next week because of the ongoing investigation.

“Given the now well-documented election fraud that took place in NC-09, Democrats would object to any attempt by Mr. Harris to be seated on January 3,” Hoyer said, adding that “the integrity of our democratic process outweighs concerns about the seat being vacant at the start of the new Congress.”

The U.S. Constitution states that the House is the judge of the elections of its members and the final arbiter of contests.

The state Elections Board has refused to certify the race between Harris and Democrat Dan McCready while it investigates absentee ballot irregularities in the district in the south-central part of the state. Harris holds a slim lead in unofficial results, but election officials are looking into criminal allegations against an operative hired by the Harris campaign.

Friday’s standoff was set in motion by the latest ruling from a state court that previously had found the elections board’s makeup unconstitutional after the Republican-controlled legislature altered the board in 2016. The court had ruled earlier this year to allow the board to remain in place until Friday while it investigates the congressional race. The latest ruling came as lawmakers enacted a new law Thursday to largely restore the board to how it operated before 2016.

Cooper started the process of rebuilding the elections board Friday by informing the state Democratic and Republican parties that he plans to create an interim panel with five members of the current elections board, unless he receives different picks from the state parties. The interim board would last until the new law takes effect Jan. 31.

He said he would appoint both Democrats and Republicans to comply with pre-2016 state elections law he says is temporarily back in force.

“All of these members have election law experience and an awareness of the circumstances around the allegations involved in the Ninth Congressional District election,” Cooper said in his letter to state party heads.

But state GOP Chairman Robin Hayes said the dissolving board’s four GOP members “will not accept appointments to an unconstitutional, illegal sham Roy Cooper creation.” Republicans instead will withhold GOP nominees until the new law takes effect, he said.

The outgoing state board refused a last-minute formal request by Harris to certify him the winner.

The elections board reorganization threatens to delay the Jan. 11 hearing. Lawyers for Harris and McCready had a Monday deadline to submit requests to the elections board for people they wanted to have compelled to appear and testify at next month’s hearing. But if the current elections board is disbanded without a new one to replace it, the board chairman or vice chairman who could issue the requested subpoenas wouldn’t exist.

Last week, elections board chairman Josh Malcolm said in an affidavit to the three-judge panel that investigative staffers — who can continue working through any reorganization — had collected more than 182,000 pages of materials in response to 12 subpoenas.

Malcolm said Friday that the elections board issued “numerous additional subpoenas” before disbanding. In a letter to Harris’ attorney, Malcolm wrote that the GOP candidate had turned over only about 400 pages of subpoenaed documents and had yet to produce another 140,000 documents. Harris also had so far failed to arrange a requested interview with agency staffers, Malcolm said.

Harris’ campaign committee has pored through about 135,000 documents that needed review, the Republican’s attorney David Freedman said Friday. Harris “has cooperated and intends to continue cooperating with the investigation,” Freedman said.

If House Democrats refuse to seat Harris, it wouldn’t be the first time a chamber of Congress delayed or rejected seating a new member. In 2009, U.S. Senate leaders initially refused to seat Roland Burris as the replacement for President-elect Barack Obama’s Illinois seat. Burris had been named to succeed Obama by Gov. Rod Blagojevich, who was eventually convicted on corruption charges for trying to sell the Senate appointment.

Democrats and Neocons Are the Biggest Losers of Trump’s Syria Withdrawal

When power is balanced as delicately as it is in the Middle East, minor changes can have major consequences. So while 2,000 troops may not sound like much, Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw them from eastern Syria has generated a rich list of winners and losers. Here’s a rundown:

Winners

Russia: Nancy Pelosi’s Dec. 20 description of the pullout as “a Christmas present to Vladimir Putin” is not off the mark. Not only has the Russian president gained leverage in Syria, he’s now the chief arbiter across the entire Mashriq, the area from the Nile to the Tigris. But the pullout alters the balance of power in another arena as well: the Black Sea. The Nov. 26 fracas in the Kerch Strait, in which Russia captured three Ukrainian navy boats attempting to force their way through what Moscow regards as its territorial waters, ended in a clear Russian victory, because it showed that it could limit access to the Sea of Azov (and therefore to the Ukrainian ports of Mariupol and Berdyansk) without NATO able to do much in response.

It’s a far cry from the heady days of February 2014, when the U.S. thought it could use the “AutoMaidan” protests in Kiev to force Russia out of its historic naval base at Sevastopol in the southern Crimea, a move that, if successful, would have virtually closed off Russian access to the Black Sea. But now the shoe is on the other foot. If the Syria pullout is a sign that the American appetite for foreign adventures is on the wane, Russia will gain even more room to maneuver—not only in Syria but in the Black Sea as well.

Iran: The last time Iran opened a corridor from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean was in the early seventh century, when it overran Syria and captured Jerusalem. Then the Byzantines counterattacked in 628, and the Arab conquests began in 632. With the U.S. out of Syria, the path is once again open from Iraq to Lebanon. It’s a victory of historic proportions.

Turkey: Reportedly, Trump’s decision to withdraw from Syria was born of a Dec. 14 phone call with Recep Tayyip Erdogan. “OK, it’s all yours,” the American president said. “We are done.”

While the Turkish president can’t be very happy to see his old enemy, Bashar Assad, return to power in Syria, an end to U.S. support for Kurdish separatists is a Christmas present in its own right.

Syria: In August 2011, Barack Obama called on Assad “to step aside” while Secretary of State Clinton entered into talks with Saudi Arabia and other “friends of Syria” about launching an armed Sunni invasion. But with Obama writing his memoirs and Clinton still nursing her wounds from 2016, the British-trained ophthalmologist can finally set about reunifying his country.

As heir to a 30-year family dictatorship, Assad was arguably little more than a Levantine Michael Corleone when he took office in July 2000. After withstanding a brutal seven-year assault by U.S.- and Saudi-backed mujahedeen, however, he’s emerged as a hero of the Third World masses.

Losers

Democrats and neoconservatives: Rarely has a strategy backfired as roundly as the Dem-neocon approach has since 2011. In Libya, Clinton spent weeks persuading Qatar to join the anti-Gadhafi coalition, only to stand by and watch as the gas-rich sheikdom massively funded Islamist militias spreading anarchy from one end of the country to the other. Decades of social progress were erased, slavery was restored and Libya turned into a happy hunting ground for Islamic State and al-Qaida.

In Syria, the U.S. gave Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other oil monarchies the green light to flood the country with thousands of Wahhabi head-choppers, unleashing a sectarian war that may have cost upward of half a million lives. In the Ukraine, Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland, a Clinton protégée, encouraged an uprising spearheaded by the ultraright that sent a legally elected president packing and ushered in a regime heavily dependent on neo-Nazi militias. In Yemen, the Obama administration couldn’t say no to a Saudi-United Arab Emirates war of aggression that, after nearly four years, has killed as many as 80,000 people and brought up to 14 million more to the brink of starvation

The results have been every bit as destructive as the shock and awe that George W. Bush unleashed on Iraq in 2003. White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney may have exaggerated when he said that Syrian withdrawal is “very popular with ordinary American people,” but not by much. Certainly, no one is taking to the streets to keep the troops in place. Democrats have suffered a major rebuff, deservedly so.

Israel: The Jewish state had counted on U.S.- and Saudi-backed rebels to bring down Assad, even providing medical treatment to wounded al-Qaida fighters and all but formally backing an Islamic State. “If we have to choose between [Islamic State] and Assad, we’ll take [Islamic State],” former Israeli Ambassador to the U.S. Michael Oren explained. Israeli Minister of Defense Moshe Ya’alon echoed the sentiment, claiming: “[I]f the choice is between Iran and the Islamic State, I choose the Islamic State.”

The result, to quote Talleyrand, is worse than a crime—it’s a blunder. U.S.-backed jihadis were always fighting an uphill battle. The more they tried to thrust Syria back into the Middle Ages, the more Christians, Shiites, Druze and women united behind the Assad government, which, despite its sins, is at least pluralist and secular. But now that Damascus has emerged victorious, the upshot is that Israel faces a battle-hardened Syrian army across its northern frontier, along with Hezbollah, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard and a sophisticated Russian air-defense system.

As for Israel’s two main allies, both are in disarray: Saudi Arabia remains on the ropes following the murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi and plunging oil prices (off 45 percent since early October), while the U.S. grapples with market instability and a wildly unpopular president. Israel is in its worst strategic position since the eve of the Six-Day War in 1967.

Saudi Arabia: The kingdom can’t be very happy now that archenemy Iran’s influence is expanding, while Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is persona non grata across the globe, thanks to his role in the Khashoggi killing. Collapsing oil prices, along with capital flight and deepening budget woes, have only added to its misery. Trump’s decision to abort Saudi-backed efforts to overthrow Assad shows just how alone and friendless the kingdom has become.

Islamic State and al-Qaida: The war against both groups was a farce under Obama and no less fraudulent under Trump. In Syria, the U.S. allowed Islamic State to fester and grow in the hope of using it as leverage against Assad. As John Kerry, Clinton’s successor as secretary of state, put it in September 2016: “We saw that Daesh [i.e., Islamic State] was growing in strength, and we thought Assad was threatened. We thought, however, we could probably manage, that Assad might then negotiate. Instead of negotiating, he got … Putin in to support him.” According to a December 2017 study by Conflict Armament Research, a London research group funded by Switzerland and the European Union, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia provided Islamic State with much of its arms and material support. Obama refused to bomb Islamic State oil fields in eastern Syria, a major revenue source, until Russia’s entry into the war finally forced his hand.

Trump, for his part, allowed a column of heavily armed Islamic State fighters, some 4,000 in all, including family members, to flee the pulverized city of Raqqa in October 2017 under circumstances that still haven’t been fully explained. Although U.S. warplanes supposedly monitor the area around its military outpost at al-Tanf in southern Syria, they did nothing to stop hundreds of Islamic State fighters from crossing in July on their way to the Druze province of Sweida some 70 miles to the west, where they killed at least 256 people and kidnapped dozens more. The U.S. says it has been unable to dismantle an Islamic State stronghold in the eastern province of Deir al-Zour because Islamic State has taken advantage of at least two sandstorms to launch major counterattacks. Sandstorms in the Syrian Desert? How could the military have known?

Now that such nonsense is drawing to a close, the one force with a clear and unambiguous reason to battle Islamic State and al-Qaida—i.e., the Syrian army, backed by Russia, Iran and Hezbollah—is finally taking the field without U.S. obstruction.

The Kurds: These are the most tragic losers of all, because they had counted on the U.S. to help carve out a homeland in northeastern Syria. While U.S. critic Noam Chomsky has called for their military protection to continue, arguing that they shouldn’t be “subjected to an attack by their bitter enemies the Turks, or by the murderous Assad regime,” such action would only further place the Kurds at the mercy of an erratic Trump administration. Their only hope is to reach an accord with Assad, and the sooner the better. If he’s smart, he’ll meet them at least halfway. (Editor’s note: The Kurds reached out to the Syrian government on Friday for protection from a possible Turkish attack.)

Wild Cards

Russian-Israeli rapprochement: Now that the U.S. is pulling out, Israel may have no choice but to attempt to reach an accord with Putin, the Middle East’s new kingmaker. It’s not so far-fetched. One Israeli in seven is of Russian extraction, and perhaps the only monument to the Red Army’s victory in World War II outside the old Soviet bloc lies in the Israeli seaside town of Netanya. Soviet-born Avigdor Lieberman, until recently Israel’s minister of defense, seems especially pro-Moscow.

As tough ethnarchs, Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu have much in common. Russia, meanwhile, would like access to Israeli technology, while Israel would like Russia to restrain Hezbollah, Syria and Iran. Hence, a Nixon-to-China moment is not out of the question.

An al-Qaida resurgence: This is not the first time al-Qaida has been down and out. During the Anbar Awakening of 2008, a U.S.-backed upsurge by Sunni tribal leaders drove it out of Iraq. While in Afghanistan, Taliban and al-Qaida leaders both lived in constant dread of Predator missiles. But then conditions shifted, and the group emerged stronger than ever.

The question now is whether another resurgence is in the works in Afghanistan, where the Taliban continue to advance; in northern Iraq, where Islamic State appears to be regrouping; and even in Saudi Arabia, where the country continues to destabilize under a vicious and isolated crown prince.

War with Iran: Open hostilities with the Islamic republic are the ultimate wild card. It may seem unlikely, given how much all sides stand to lose—not only Iran, but the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Israel, too. But its irrationality probably makes it a more rather than a less likely scenario.

Acclaimed Author Amos Oz Dies at 79

JERUSALEM — Israeli author Amoz Oz, one of the country’s most widely acclaimed writers and a pre-eminent voice in its embattled peace movement, died on Friday after a battle with cancer, his family announced. He was 79.

His daughter, Fania Oz-Salzberger, announced her father’s death on Twitter.

“My beloved father, Amos Oz, a wonderful family man, an author, a man of peace and moderation, died today peacefully after a short battle with cancer. He was surrounded by his lovers and knew it to the end. May his good legacy continue to amend the world,” she wrote.

Oz was known around the world for his dozens of novels, essays and prose about life in Israel, including a well-received memoir, “A Tale of Love and Darkness.” He won some of the literary world’s most prestigious honors, including the Goethe Prize and the French Knight’s Cross of the Legion D’Honneur, received honorary doctorates and was a perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature.

Oz was born in Jerusalem in 1939, the son of immigrants from eastern Europe. As a teen he rebelled against his upbringing, looking to put behind what he felt was his parents’ insular world of immigrants and drawn to the young pioneers who built the early state.

“I secretly dreamed that one day they would take me away with them and make me into a fighting nation too. That my life too would become a new song, a life as pure and straightforward and simple as a glass of water on a hot day,” he wrote in his 2002 memoir.

He would complete high school at Kibbutz Hulda in central Israel, and return to the kibbutz after completing his mandatory military service in 1961. While working in the farming community’s cotton fields, he published his first short stories.

After earning a degree in literature from Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, he would spend 25 years on the kibbutz, dividing his time between writing, farming and teaching at the community’s high school, according to his website.

As a reserve soldier in a tank unit, Oz fought in the 1967 and 1973 Mideast wars.

In a career spanning half a century, Oz published over 35 books, including 13 novels as well as children’s books and collections of short stories, and hundreds of articles on literary and political topics. His works were translated into more than 40 languages.

His works included “In the Land of Israel,” a work that chronicled his travels and interviews with people throughout Israel and the West Bank in the 1980s about the country’s past and future; “My Michael,” a novel about a troubled marriage in 1950s Jerusalem, and “A Tale of Love and Darkness.” That 2002 memoir, recounting his childhood in Jerusalem and the suicide of his mother when he was 12 years old, won him the Goethe Prize and other recognitions, and was adapted into a film starring Natalie Portman.

Oz was a leading voice in Israel’s peace movement and a friend of the late Shimon Peres, a former prime minister and legendary politician who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to reach a deal with the Palestinians. Oz frequently wrote essays and delivered lectures urging the country’s leaders to establish a Palestinian state as part of a peace agreement with Israel.

In a 1998 interview, he lamented the deep divisions in Israeli society — a prescient observation that remains true to today.

“We have not yet established the rules of the game in 50 years,” he said. “You could hardly get two Israelis to agree on the kind of Israel they want.”

In a 2001 interview with The Associated Press, Oz said Israel must wean itself from the view that the West Bank and Gaza were assets to be traded for peace and instead should just be given away.

“I think today that Israel should draw its own borders, withdraw to them, and if needed defend them,” Oz said. “If we’re going to fight, Israel without Nablus and Gaza is stronger than with Nablus and Gaza. Stronger, more unified, more just.”

He was among the founders of Peace Now, a leftist organization that opposes Israeli settlements in the West Bank, and was a leading voice in the 2003 “Geneva Initiative,” an unofficial peace plan reached by leading Israeli and Palestinians. He also was a supporter and activist in Meretz, a dovish Israeli political party.

In recent years, he, along with fellow authors David Grossman and A.B. Yehoshua, became pillars of the country’s peace movement, which has grown increasingly marginalized over the past two decades.

Israel’s leading human rights group, B’tselem, called a “beacon in the struggle against the occupation.”

Tributes to Oz poured in from around the world.

“A story of love and light and now great darkness,” Israeli President Reuven Rivlin wrote on Twitter.

“We are mourning the passing of Amos Oz, a wonderful Israeli poet and novelist, a towering voice for peace,” wrote the European Union’s delegation to Israel. “May his memory be a blessing.”

Trump’s Environmental Rollbacks Are Already Taking a Steep Toll

A New York Times investigative report on President Donald Trump’s nearly two-year environmental record and how his industry-friendly policies are impacting communities nationwide, published in the Thursday paper, “reminds us that the Trump soap opera has dire real-world consequences.”

That’s according to 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben, who added on Twitter that “futures are foreclosed because he’s a tool of dirty energy.”

Good solid journalism reminds us that the Trump soap opera has dire real-world consequences. Futures are foreclosed because he’s a tool of dirty energy https://t.co/4Orohw97eM

— Bill McKibben (@billmckibben) December 27, 2018

The “must-read” report focuses on examples from California, North Dakota, Texas, and West Virginia, with special attention paid to policy changes at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Interior Department—which have both seen Trump-appointed agency heads resign amid numerous ethics probes.

Acknowledging a previous Times analysis of the 78 environmental rules—including many implemented under former President Barack Obama—that the Trump administration and Republican-controlled Congress have worked to eliminate, the report details how the EPA, at the behest of industry lobbyists, quashed a ban on the toxic pesticide chlorpyrifos, which has “sickened substantial numbers of farmworkers” in rural California, where more than a third of U.S. produce is grown.

While that move is being contested in federal court, it exemplifies how the administration has often defied scientific findings and warnings in favor of demands from pesticide producers, fossil fuel developers, and other polluting industries. As the Times put it:

Since taking office, Mr. Trump has consistently sided with powerful economic constituencies in setting policy toward the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the presence of chemicals in our communities.

In the process, he has frequently rejected or given short shrift to science, an instinct that has played out most visibly in his disdain for efforts to curb global warming but has also permeated federal policy in other ways.

The Times also examines Trump’s rollbacks—and the subsequent public health consequences—of air quality regulations that aimed to reduce dangerous levels of sulfur dioxide pollution from coal-burning power plants in Texas; policies crafted to clean up West Virginia waterways polluted with arsenic, mercury, and selenium by the coal industry in West Virginia; and limits targeting flaring and leaks of methane on federal or tribal lands, including the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota.

Considering the Interior Department’s September 2018 reversal of such limits after complaints from Big Oil, Walter DeVille, who lives on the reservation and whose wife has been diagnosed with a respiratory condition common among oil field workers, told the Times, “We are sort of powerless… This is our reality now.”

A Times summary highlighting five key takeaways from the report—which pointed out that while the consequences of Trump’s polluter-friendly policies “are starting to play out in noticeable ways in communities across the United States,” the full impact “of the Trump-era policies may not be fully apparent until years after Mr. Trump leaves office”—emphasized:

Trump has quickly undercut Obama’s legacy;

Environmental impacts span the country;

The rollbacks touch air, water, chemicals, and climate;

The decline of coal has not been stopped; and

Progress is slowing—but there’s still progress.

Although the “incredible” and “devastating” report—produced by Eric Lipton, Steve Eder, and John Branch—garnered significant praise, some more cautious language choices also elicited criticism. For example, the Times reads, “Beyond the glare of Washington, President Trump’s retreat on the environment is unfolding in consequential ways for the health and safety of Americans.”

While characterizing the report as “a great package on the real-world, human costs of Trump’s gutting of pollution regulations,” author and climate activist Alex Steffen noted, “Trump is not ‘retreating’ from environmental responsibility, he’s overtly attacking it.”

This is a great package on the real-world, human costs of Trump’s gutting of pollution regulations.

Important language point, though: Trump is not “retreating” from environmental responsibility, he’s overtly attacking it.https://t.co/xTzMP2va35

— Alex Steffen (@AlexSteffen) December 26, 2018

The ‘Highest Danger’ of the Cold War Isn’t Behind Us

The odds were stacked against the two authors of “The Kremlinologist: Llewellyn E. Thompson, America’s Man in Cold War Moscow” when it came to treating their subject with anything resembling journalistic precision or objectivity. That’s primarily because they resembled their subject a little too closely—in addition to being the book’s co-writers, Jenny and Sherry Thompson are also Llewelyn Thompson’s daughters.

No matter. As Robert Scheer puts it in this week’s episode of “Scheer Intelligence,” in which he interviews the Thompson sisters, the pair produced a “first-rate work of journalism” as they profiled their father.

Jenny and Sherry Thompson tell Scheer that their shared impulse in taking on the project was part intellectual and part emotional. The senior Thompson, who was stationed in Moscow as the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union during two crucial stretches of the Cold War, died more than four decades ago, so the sisters were invested in his memory as well as his legacy. “We started this whole project for our families … we wanted to discover who he was,” Sherry says. “It really needed to be a proper book.”

That it is, and then some. According to Scheer, who notes the book’s positive reception in the diplomatic community, “The Kreminologist” ranges far beyond a professional profile of Thompson himself. In fact, Scheer says, it’s “the indispensable book to understanding the trajectory of the Cold War.” Most important, it capably debunks the lingering “fundamental fallacy” about a conflict that remains dismayingly relevant to this day.

Listen in on their discussion to find out what that central misconception is, to hear the Thompsons’ take on whether communism is best seen as a nationalist or an internationalist phenomenon, and why they think the current moment is closer to the most dangerous point in the Cold War than many Americans realize. You can also read a transcript of the interview below:

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence. And I’ve got a remarkable book we’re going to talk about today. It’s called The Kremlinologist. It’s the story of maybe one of the most admirable figures we’ve had in the foreign service agency of the State Department, and foreign service officer, a man named Llewellyn E. Thompson. At one point he was our ambassador in Moscow, the most critical point in the history of the Cold War, threatened with nuclear disaster and everything else. And the thing that made me suspicious of this book at first, it happens to be written by his daughters, who also were there, Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson. And my first response was, OK, they’re going to have very nice things to say about their father. And, boy, was I wrong. This is the indispensable book to understanding the trajectory of the Cold War: what was it really all about? And in particular, about a fundamental fallacy in the Cold War. So let me bring you two in, Jenny Thompson and Sherry Thompson. We’re doing this by phone. But what you did–and I know from your introduction and so forth–you spent at least 13 years on this; you had access to your father’s papers; he wasn’t a person to write a lot about what he was doing. And you’ve come up with maybe the clearest insight into what I would consider to be the essential folly of the Cold War. That we could be virtuous at the same time as we were conniving. Can you comment on that, or bring us into how you came to write the book?

Sherry Thompson: Sure. This is Sherry. We really started this whole project for our families. Because our father died quite young, so we wanted to discover who he was, and what his career was about, and we wanted to share that with our families. And it wasn’t until we actually started interviewing people that we realized it really needed to be a proper book. And I think that’s how it became as much a history of the Cold War, with his life as a thread running through it.

Jenny Thompson: This is Jenny. We also had to meet in Washington and go to the archives, and do the research there. And when we started, we didn’t really think about footnotes and references, and then we realized–especially since we were his daughters–that we had to back up everything we said with some sort of citation or reference. So that’s another reason it took so long, and also because we were both working and raising families, and–not much time.

RS: And let me just say at the outset, this book is being honored by professionals in this field, the American Academy of Diplomacy. And they generally honor an exemplary member of their own tribe, and you’re being honored days after we do this interview here in mid-November, in Washington. And again, I want to repeat–I’m not saying this in just an off-handed way. You know, I read this book right through, and I am enormously impressed with it. And what I’m impressed with–not that it gives us a great insight into your father, and you really did a first-rate job of journalism, is what this book is. It almost confuses it to mention that you’re talking about your father, because you’re actually quite objective about his limitations, his strengths, his–you know, as a human being. So, did you get a great deal of access and support in writing this?

JT: Not really. Not–I mean, we interviewed his colleagues, obviously, and we interviewed the people that worked with him. Chip Bohlen has passed away, but he wrote a book that we used, also. But we had the interviews, but nobody actually helped us to write the book or organize it.

RS: Well, OK, then–

ST: What we did have help with was, after we finished the draft, we sent chapters out to various people, including Chip Bohlen’s daughter, to read what we had written, to make sure that we weren’t saying something too outlandish.

RS: Well, I don’t think you say anything outlandish. But you do say things that are quite provocative. And it seems to me the basic issue raised by your father was that the whole construction of the Cold War was built on a fallacy. I don’t know that he would use that word, because he was witnessing it as it evolved. But was communism nationalist or internationalist? And speaking primarily about its fountainhead, the Soviet Union. And the assumption of the Cold War was there was this ideology of communism; the Soviet Union had adopted it, and this led inevitably to a universalist, expansionist position. But as the book moves along, we find that the Soviet Union was largely a nationalist phenomenon, and that inevitably got into conflict, first with Tito in Yugoslavia, another communist, but he had fought his own war against the Germans; and then of course the Sino-Soviet dispute. But then even when you get up to the Vietnam War, clearly the Vietnamese communists were Vietnamese first, and nationalists. And I think your father–and he says it in his writings and so forth–felt this was the great era we were making, that we underestimated the nationalist component. Is that not one of the important messages of your book?

ST: Yes, I think it is. I think that there was always this tension between the nationalist impulse and the internationalist impulse, if you will. And our father was very–well, he argued very strongly in favor of looking at our policies to make sure that we would encourage the more nationalist view. And of course nationalist has lots of connotations right now, but the nationalist view which was more benign than the ideological communist view, yeah.

JT: I would add that he was also very much aware of the tension between the Soviet Union and China. China was a much more revolutionary sort of communist country, and they were very much for exporting communism, often criticized the Soviet Union for not doing enough on the, you know, pushing it internationally. And this was the sort of tension between them, and our father also would advise that we had to do everything possible to encourage the Soviet Union to not go the Chinese way.

RS: Well, and let’s stick on that point, because it’s the key era of the last 50 years; maybe it’s an era we’re making now in our appraisal of Russia without communism. We have a hard time understanding anyone else’s nationalism. You have, even China–and there your father probably was incorrect, I think–the idea that somehow they were so slavishly involved with Marxist, Leninism, ideology and so forth; well, no. The main reason that they were hostile to Russia, they used that argument, but it turned out in fact they have Chinese nationalists. And one of the ironies of the whole Cold War history, as we fight this long war in Vietnam against Vietnamese communism, not because we think the Vietnamese have an army or a navy that can hurt us, but because we think they’re an extension of Chinese communist and Russian communist power. And we lose the most ignominious defeat that we’ve ever had in Vietnam. And what happens? Instead of the Vietnamese communists attacking San Diego, the Chinese and the Vietnamese communists go to war. They are fighting over their border, and they’re still fighting over islands that they both claim. So even in the case, or maybe particularly in the case of China, this argument your father was advancing, that nationalism in some sense supersedes communism or ideology, really was the important correction, and that the U.S. government did not heed, at least at the highest level.

JT: Yeah, I would say that you’re right. And I think, as you mentioned, Russia today, I think people don’t really realize that Russia today is not the Soviet Union. It doesn’t profess an ideology. Obviously it has nationalist interests. And because of the sort of Cold War mindset, it’s easy to whip up anti-Russian sentiment, simply because we’re ready to accept that. We were accepting, you know, we were anti-Soviet during the Cold War. I think what we need to do now is be very careful, because we’re getting into a position of another arms race with Russia today, and also the possibility of rising rhetoric and making the tensions higher will, could possibly lead to even nuclear war. And we’re kind of in the same position we were in at the highest danger of the Cold War.

RS: I think that’s an important observation, and it’s one your father would, I think, be making now. Because there was a wing of the State Department that certainly was naive, and even apologetic, about the Soviet Union. That was not your father; he was tough-minded, independent, saw the failings quite clearly. But the key operative thing–and this is, amazingly enough, it was Richard Nixon who kind of embraced this, both for Russia and China–we could do business with them. We could live with them, if we understood their nationalism. And where we got into trouble, I think, in the mind of your father, was when people like Paul Nitze, and the neocons later, and everything, put their ideology and then assumed the other side’s ideology, and boom, we’re off to, on the road to World War III. And your father’s wisdom was, you know–and reinforced as he learned more and more, and rose higher and higher in the government; he got to be quite high under Lyndon Johnson, knew a lot about the covert operations and everything. And he came to two conclusions. One–and this was a very important observation in your book, I think–he understood about the Soviet Union, that there was an enormous contradiction between their appearance, their illusions, what they presented themselves as, and what they really were. And it’s by the end of your book, when you’re discussing Vietnam and covert operations–your father comes to this really depressing conclusion that, you know what, we do the same thing. Again, I don’t want to put my own interpretation here, but it was quite clear at the end of the book that he was shocked that there’s that same kind of genre of deception, self-deception, on the part of the elites of both of these societies.

ST: Well, I think that he did have some disillusion when he became part of the 303 Committee, which is the covert operations, committee that oversaw, OK’d covert operations. And so he was [in] a much larger role than when he was just dealing specifically with Soviet affairs. But it also, it’s a speculation on our part, but he complained a lot about having to do that job. And I think that part of that was because of that. And he saw his role as constantly being the guy in the middle who was trying to explain the Soviets to the Americans, and the Americans to the Soviets.

RS: But not just that. I mean, he–he–look, there’s a subtext in your book. There are these foreign service officers, like your father, Llewellyn Thompson, a defender of historical accuracy, of scholarship, getting it right, and respecting other people’s history. And that is not the dominant, or it’s not the ever-present, caution in the pursuit of foreign policy, to put it mildly. And I think that was the struggle he was having. And when the Lyndon Johnson administration, when they said look, let’s put this guy in with the–tell us about the 303 Committee, and how it developed, and what it was doing. And he was really cautioning against the dangers of that approach.

JT: The 303 Committee was a committee in the State Department that was supposed to oversee CIA operations, so the CIA would have some oversight. All the things in the 303 Committee are still top-secret; it’s impossible to get ahold of them. Some of this came out during the Church investigations, but it’s still impossible to know exactly what they discussed in, you know, in all of those meetings. One of the things that we learned in doing this biography was the necessity to have empathy for the other. And I think this is, this is a major lesson that we learned from the book: you have to try to understand the other, and to anticipate what the consequences might be of any particular action that you contemplate. Long-term consequences are really overlooked these days; everybody goes for the short-term gain, and they don’t look at the long, long picture. And this is one of the things that Thompson did quite well; he would always look at where this would lead, and therefore, his advice was based on that.

RS: Your father was–understood bad things happen, and there are bad people. He was quite aggressive in confronting them; he was quite brave. He’s the one who stayed in Moscow when the rest of the embassy and everybody else went off to safer quarters. He’s a guy who went through the war, saw the horror; he also saw the horror of Stalinism and, you know, the torture of people and so forth. So this is a tough cookie, your father. On the other hand he said, wait a minute, let’s not get such a superiority complex here that we are the center of virtue and these people have no claim on anything. I mean, that was really his wisdom. We had others like him, but he might be the person, if we had listened to–it wasn’t just we would have had a more sensible policy towards the Soviet Union; we would probably not have gone into Vietnam. We would not have overthrown Mossadegh in Iran; we would not have done a lot of the serious mischief we’ve done in the world, because he knew that derring-do, undercover stuff had consequence.