Elissa Altman's Blog, page 3

February 19, 2016

A Moral Imperative and a TEDx Talk

Click here to view the embedded video.

Some years ago, Susan and I went to visit one of her cousins, an older lady, at the assisted living facility she had moved into a year earlier. Unlike many seniors who have trouble keeping weight on, Susan’s cousin, who bore the faintest resemblance to Dick Butkus, had gained eighty pounds.

Eighty. EIGHT ZERO.

In a year.

Why? Because the facility where she was living fed her nothing but white carbs, three times a day, with snacks in between. Morning, noon, and night, she ate white bread, white potatoes, white pasta, white rice. Over and over again. Her processed food diet, which delighted her — who doesn’t like an endless intake of comfort food? — was ultimately nothing more than sugar, in varying forms, and nothing else, all day every day. When we went to see her, she could barely walk. I can’t recall whether or not she was a diabetic when she arrived, but by the time she left for the cemetery, I believe she was.

“At least I’m better off then she is,” this cousin said to us, pointing to a gaunt woman whose coloring could only be described as pearl gray. She sat alone, a surgical table pulled up to her chest, sipping Ensure — the first ten ingredients of which (barring water, which is number one) are sugar and fat — through a straw.

That day was a personal turning point for me; bells, lights, and whistles went off all at once. In this country — this great, proud, wonderful, modern, devout, deeply religious country — that is my home, we don’t care much for senior citizens. They’re not particularly cute and cuddly, like infants. They move more slowly, and sometimes can’t remember. They’re an afterthought, an annoyance, an inconvenience. They’re living longer — imagine the nerve — and thus they drain the system. (This is not my argument, but I have heard it repeatedly.) And so, we do everything we can to avoid them and the subject of them. By that, I don’t mean that seniors don’t show up in our political discourse; they do, in terms of social security and medicare. (These are not, as some folks like to say, entitlements; these are implementations of our human value system writ large. We take care of infants in need; if we are to call ourselves an ethical, moral society, we must take care of senior citizens. Period. WWJD, right?)

But I’m not talking about government responsibility. Where seniors don’t show up is in our culture, and at the table. Once that assisted living facility door closes, and once that apartment door shuts, seniors are effectively removed from the world around them. We feed them cheaply, as though what they eat is simply fuel, devoid of cultural connection and sustenance. They grow isolated; they grow ill; they die, often alone, the links to their families and their communities of origin, broken.

A few years after our visit to see Susan’s cousin, I was contracted to write a book on this subject, about which I have grown passionate; I called it Beyond the Schoolyard. For months, I researched and conducted interviews; I read statistics and cohort analyses until my eyes crossed. And somewhere along the line, I came to the realization that this book wouldn’t — or shouldn’t — be about numbers; it would have to be personal, and experiential. Because the way we feed seniors — the largest, actively growing demographic in this country, with almost 50 million among our population at this moment — is a deeply personal issue. The story doesn’t start in the assisted living facility or in the apartment; the story begins at the table, in the homes of our childhoods and in the homes of our parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles. The story of feeding our seniors — bringing them to the table and keeping them there for as long as possible — starts at the most humane, human of places: at what the late Marion Cunningham called The Modern Tribal Fire.

Over the last year, I have written a monthly column for the Washington Post food section, called Feeding My Mother, about the vagaries of feeding an older parent — nutritionally, emotionally — who has had a peculiar lifelong relationship with the table. A few weeks ago with the help of Edible Reno Tahoe publishers Amanda Burden and Jaci Goodman, and Dr. Bret Simmons of the University of Nevada Reno, I was honored to give my first TED talk on the subject, at TEDx UNR, alongside other speakers from every walk of life and (thrillingly) both sides of the aisle — Democrat, Republican, Liberal, Conservative — on every issue ranging from navigating the healthcare system from the point of view of a hospital CEO battling cancer, to fighting child sexual abuse, to being a football player and coach who happens to be gay. What bound us was not the fact of our seemingly disparate subjects; it was the intense humanity that plaited our subjects together. I’ll never, ever forget it (and not because I had to memorize my twelve minute talk and then deliver it in front of fourteen hundred people, without passing out).

Beyond the Schoolyard is on the shelf for the moment; I had to first finish my next memoir, Treyf, which is coming out in September 2016. But the issue of bringing seniors to the table is one that is not going away for me, nor for you. Beyond the Schoolyard will, I suspect, ultimately take a much different form, although the message will be the same: bring seniors to the table. Nurture them. Feed their souls and spirits, and you will not only nurture their hearts; you’ll nurture your own.

January 13, 2016

New Year, New Who?

The new year started with a detox, which didn’t go well.

Day one was like being shot out of a cannon: a high-fat green smoothie for breakfast that tasted, as my friend Lisa says, like lawn clippings.

I was hoping that our new Vitamix would do something spectacular to it, like turn it into poached eggs on toast.

We can make it better, I said to Susan, who managed to drink the whole thing; I choked down two gulps and poured the rest down the drain, praying that the chia seeds didn’t hold a convention and plug it up.

Day two began with trepidation: a high-fat fruit smoothie that was more palatable. Even throwing a whole quarter lemon — pith, peel, and all — into the Vitamix didn’t turn me off. The result was pleasant enough — fruity, a little bitter — even though the chia made the consistency more like drinking almost-set jello than a smoothie.

Day three started with the same thing, except that it actually began on the night of Day two, when Susan dutifully soaked the chia seeds and the nuts (almonds, Brazil nuts) to make them more digestible. Which they were, mostly. Susan gets up every morning at five a.m. for a very long daily commute into New York, and the first few days I got up with her as a show of solidarity while she stood in the kitchen, bleary-eyed, and turned on the Vitamix long before the break of day. She put it on the smoothie setting, dumped in the ingredients, flipped the switch, and woke the neighborhood.

Lunches and dinners were easier; there was always a lean protein (4-6 ounces; I weighed everything), salads, greens, non-starchy vegetables, no grains, no dairy, no gluten, no wine, no fruit, except for the tomato that was part of one of the dinner recipes. It’s January in New England: Go find a fresh, non-mealy tomato that doesn’t taste like you’re chewing on cotton balls. There’s a reason why we eat food that’s fresh and seasonal; this is just a very small part of it.

We made it into day four; Susan’s mild sugar cravings had in fact slowed. Mine were non-existent to begin with because I have no sweet tooth. Never have. At the end of the four days, I had gained a pound; Susan lost four ounces.

We were depressed; we’d had enough.

This particular detox is part of a diet that I hold — and I’m quite serious about this — in very high esteem; the folks who have developed it did so as a way to help people unravel severe sugar addiction and blood sugar issues which come as a natural by-product of the SAD (Standard American Diet). It’s brutal — it has to be; even though we don’t eat the SAD in my house by a long shot, I experienced a massive migraine by day two and some flu-like symptoms that go hand-in-hand with detox — and for the people who desperately need it, I believe it works and results, ultimately, in saner, less deadly eating habits and lower blood sugar, industrial food complex be damned.

But in our house, like many detoxing households, we don’t have deadly eating habits; we have good eating habits. To be clear, it was not a total flop for us: we came away from it — even just four days of it — with a better sense of portion control and the ability to acknowledge when we’re actually hungry versus bored, which helps us make better choices about what, and when, to eat. And that’s key.

So the reasons behind our doing the detox were murky. Sure: we wanted to feel clean, and a bit lighter after the onslaught of rich holiday foods. But again, we don’t have the standard American diet; the quality of the food we eat is very high because we are lucky enough to be able to afford it; our portions are never outlandish, even at the higher end of normal; we don’t need to detox from sugar or dairy — I’m not much for either and even when I eat cheese, it’s generally only goat or sheep, and almost always raw. I eat gluten free because bad things happen if I don’t, and they have since I was three years old — this is not something I need to prove to some self-anointed, self-appointed naysayer (and if you are GF, neither do you) — and I almost always feel better when I eat more fish, less meat, and I move my body: walking, light running, yoga. Being outside.

So, why the detox? Why the diet?

Because, like many women of a certain age — I’m 52, and a former serious athlete (tennis, squash, swimming, skiing) — I look in the mirror, and it appears that my bubbe from the old country is staring back at me, even though she’s been dead for years. I’m carrying fifteen extra pounds that, no matter what I do — detox, no detox; five-day-a-week workouts; small portions; less wine; on and on and on — I can’t drop.

How’s the gym going, my mother asks every day when I call to check in on her. This is her backhanded way of asking: lose any weight lately? My mother is five foot five (she’s dropped two inches in recent years), rail-thin, slender, an ectomorph. She wasn’t always; as a child, she was round and chubby, and carried her weight in her cheeks and her belly, the way I do. She became a singer and a model; she starved herself into size two thinness, which is where she remains, even now.

Dieting works, she says to me, apropos of nothing. Just look at me.

So I look at her. And I look at the magazines and blogs and books that dangle the promise of a different, more fabulous me over my parched, non-pouty, middle-aged lips like I was Tantalus himself.

Somewhere in the recesses of my brain, in the twisted part of my cerebral cortex that understands that skinny is better and beautiful is best and young is the prize that every woman wants, I have received and absorbed like a sponge the message that I am not thin enough; I am not pretty enough; I am not young enough. If I drop fifteen pounds, I’ll be thirty-five again. Almost certainly, my blood pressure will come down; I’ll get off my beta blocker and my statin, and that’s great. But that’s not why most women of a certain age, once a year, hit the reset button, and try again.

And it’s not why I do it.

This is the root of it; the gnarly spider’s web that catches us in its sticky threads and won’t let us go.

January 1st: we detox. We diet. We wipe the slate clean. We inhabit the promise of being someone else: the me without the fifteen extra pounds, the double chin, the aching joints, the graying hair, the dimming complexion.

We inhabit the promise of happiness, of acceptability.

We become the woman we used to be.

Would that we could simply take care of our bodies and souls as the years pass — eat well, be physically active, love, be loved, take time to breathe and slow down — and be who we are.

December 24, 2015

My Holiday Wish For You

I wish for you this holiday season…

A recipe that takes over your kitchen at least once a week

A closet clean-out (and donate everything else)

…and all the love your heart can muster.

However and wherever you celebrate, may joy be yours.

December 16, 2015

Quiet in the Storm

Months ago, when the manuscript I’ve been working on was not yet finished, I signed up for a three-day silent meditation retreat at the Garrison Institute, a former Catholic monastery overlooking the Hudson River. I knew the retreat leaders well: Sylvia Boorstein and Sharon Salzberg have been among the foremost teachers and interpreters of the Metta Sutta for decades, and whenever I’m at a loss — whenever my heart cramps with fear and upset, whenever the tinge of angry bile threatens to choke me — I pick their books off my shelf and read them.

Back then, when I signed up and plunked down my shekels and convinced Susan to come with me, I had no idea where I would be once the retreat rolled around: I didn’t know whether my new book would be done, I didn’t know if I’d still be chained to my desk, I didn’t know whether I’d be fighting another in a long line of the lung infections that have plagued me now for three years, I didn’t know whether I’d be drowning under essay and article deadlines. I didn’t know whether I could disentangle myself from my mother’s gravitational orbit for three days without causing her major upset and tumult. (First stop meditation, she said. Next stop Moonies.) This is the quandary we face when we plan ahead: will we or won’t we? Can we or can’t we? Should we or shouldn’t we? Calendars are a leap of faith, a construct of optimism and whim: we will put one foot in front of the other, the clock will tick and time will pass; one hundred dinners will be eaten, one hundred dirty dishes washed, the sun will set, the sun will rise. Everything passes. Impermanence.

It has taken me longer than I expected to write Treyf (which is partly why my presence here has been so infrequent; I’m back, though); when I began making notes for it, a little while after Poor Man’s Feast came out, I was certain that I knew exactly what I wanted it to be: a story of forbidden foods in my life and the lives of my parents and grandparents; A walk through the Talmudic minefields of the culinarily taboo during my childhood in 1960s and 1970s Forest Hills, New York — the days of key parties and fondue and Manson and Son of Sam and the 1977 Yankees; children where I lived grew up very quickly — when my father made Spam and eggs for breakfast just a few hours before my grandmother lit our shabbos candles and we ordered pizza for dinner, half sausage and half not. It was meant to be about changing mores at the table, about the cultural shape-shifting that takes place as the old gives way to the new, and we look back at the past from the vantage point of the future. How much do we cling to; how much do we relinquish without forgetting who we are? The table is our anchor, our silent witness knitting together our stories like Madame DeFarge as the days and months unspool; the table watches us change and grow at the most visceral level.

This is what Treyf was meant to be, and it is. But it also took on a mind of its own. The act of writing, like the act of cooking, forces you to come face to face with fluidity and change. You cede control to the work itself. You stand back and trust that the wormhole your narrative is dragging you down (try and fight it; good luck with that) is lit from within by a force you are acquainted with only in the dead of night, in your deepest dreams; you might not wind up where you planned to be and insofar as the physical process of writing is controlled by you, you very often will end up in another country entirely, as though a total stranger was driving your bus across borders you’ve only ever known to be forbidden.

So Treyf became the story of rule-breaking well beyond the table, and how — if we are going to set our demons free and step into a future that is uniquely ours and that makes us who we are — we have to make a choice between what was, and what is. This, of course, is never easy, because change sucks and most of us hate it and fight it tooth and nail (I know I do). Also, people want you to be who they want you to be; you might have noticed that. They want you to remain who you always were; it’s tidier for everyone if you just stick to the script that they’re familiar with. When you step out of your own comfort zone — when you break the rules — you push other people out of their comfort zones, too. You risk disappointing them. And then, if love is really there, you wish each other well and you grow together into a new and different place. Or you don’t. So the writing of Treyf was complicated. As Faulkner (I’m pretty sure it was Faulkner) once said it whupped me but it ain’t killed me. Although, given the seven very serious lung infections I’ve had since 2013, it came close.

And then Treyf was finished and I looked up and the world had completely changed (again) while I was busy writing; there was Paris and Bataclan and refugees and San Bernardino. There was Trump, and astonishingly frightening, xenophobic threats the likes of which my grandmother used to reminisce about when I was growing up. There were close friends who were suddenly fighting various illnesses, and children of other friends who were undergoing scary surgeries. Everything suddenly seemed much louder and almost blinding with intensity; non-stop violence and the sort of patriotic rage that my great uncle watched unfold on the streets of Vienna in 1938 shrieked and shouted at me, and I could barely make out what it was all saying in the way that a vindaloo can be so incendiary, you can’t actually taste the lamb. To calm myself and turn down the screeching noise, I stepped into our kitchen the way I always do when I’m unsettled and sad, but I forgot to focus on my task: I immolated the chicken and carbonized the steak and turned the pasta into spackle. One night, I boiled my favorite saucepan dry and then black, and set off the smoke alarm; I knocked over three expensive Burgundy glasses that fell one by one like dominoes before shattering into a million shards.

This is what happens when you’re pitched off your center, when you’ve lost your balance, when you stop paying attention because if you don’t, the glare will be too bright, and the stimuli too stimulating. I looked at the calendar hanging on the fridge; months had passed since I signed up for the retreat at Garrison and suddenly, it was just days away. I had so much to do: revisions on Treyf, shopping for the holidays, filing my year-end articles, making donations to my favorite organizations. It would keep: Susan and I packed and went to Garrison and sat in silence for three days; we listened to Sharon and Sylvia and read the Metta Sutta.

We watched the sun rise and set and rise and set over the Hudson the way it has forever, and the way it always will; we put one foot in front of the other and moved forward with the calendar, into the end of the year.

October 21, 2015

Ghosts at My Table

In the fall of last year, Susan and I had a friend visit us for a few days; Simon, who is a remarkable line and watercolor artist specializing in, among other things, dig-side archeological academic renderings and sketches, was going through a challenging time, and we invited him to spend the weekend with us in Connecticut. On Sunday, before we put our friend back on the train for home, we visited the Yale Center for British Art, where, fortuitously, a show called Of Green Leaf, Bird, & Flower: Artists’ Books and the Natural World, which examine(d) the intersection of artistic and scientific interest in the natural world from the sixteenth century to the present day, was on exhibition. Many of the artists’ books were those belonging to amateur naturalists — women and men, mostly from the so-called leisure class, who, dating back to the late 1500s, took their pencils and nibs out into the fields and hills, and watched and looked and drew and clipped and tacked what they found into books. The books — leather-bound, small, like the modern-day Moleskines that many of us carry in our back pockets — were stained with time and sweat. They had a distinctly personal and almost illicit aura; looking at them made me feel both exhilarated and wary, like I was reading someone’s diary and being transported to their past.

There was an audio component to the exhibition: the curator, Elisabeth Fairman, included selections from The British Library’s Sonic Migrations, a massive collection of recorded environmental and wildlife sounds, which complemented the show: you could not only see amateur naturalist sketches of the European Robin, you could listen to it too. Among the audio selections was a birdsong — I don’t know whose it was — recorded in rural England in the early 1940s. As I stood there, headphones on and captivated by the sweet singing, I began to hear a distant low drone, a rumble I thought I was imagining until it grew louder and louder, disappearing for a moment and then returning only vaguely and remotely, until it was gone in a haze. According to the accompanying exhibit information, a squadron of RAF planes had flown over the recording site, maybe a field somewhere near Sussex — my geographical and admittedly romantic guess; Virgina Woolf’s Rodmell was in Sussex — on their way to Germany to execute a bombing mission.

Did they return? Was that inadvertent recording the last earthly trace of one, or two, or more of them?

I listened to it over and over again. I called Susan and Simon over to hear it. We passed the headphones back and forth and stared at each other, a little stunned and teary and wide-eyed, as though we had not only seen the past and heard it, we had somehow seen through it, from a different place in time and space. It was thrilling; it was terrifying. It made my stomach plunge and my throat tighten and the hair on my neck stand up. More than anything else, I found myself longing to know their fate: what were their names? Where were they from? What had they eaten that day?

Did they come home?

Lately, I’ve been turning a lot to the past, and considering its significant role in the present: I’m in the end-throes of writing my second memoir (an explanation for my infrequent appearance here), some of which takes place in a long-ago time that was not mine per se, but that led up to, influenced, and became mine. Discussions of craft aside, how is it possible to write memoir from a time so distant that one has not actually, physically, been there? Because we — all of us, to a number — exist in a world entombed by story and history; none of us is born in a vacuum. We are the sum of the people and the stories that came before us; their histories make us who we are, for better and worse. I know that my father, a night fighter pilot during World War II who knew how to fly a plane before he could drive a car, came home on leave and was picked up by my grandfather at Floyd Bennett Airfield in Brooklyn; I know that when a Marine guard saluted my father as he came through the civilian gate, my grandfather watched closely, and said to his son, Velcome home, Captain America. I know this not because I was there, which I was not, but because my father fed me this story over and over again, like pabulum. And because I was not there, I can only imagine the supper that my grandmother had prepared for his return, because on the one hand, he told me she did, but on the other, she fed it to many of us — myself included —repeatedly through the years, as though it were a sacrament, an edible talisman, an anchor: chicken soup strained and strained again until it shimmered like liquid gold in the early evening light that came through the window off the fire escape facing Coney Island; the soup chicken, its skin removed, eaten warm with a slice of challah; a piece of chocolate cake from Ebinger’s; a glass of Sweet-Touch-Nee tea.

(They were not so big on vegetables in my grandmother’s house.)

It’s inevitably at the table where what we came from and who we turned into gets spun like silk into stories. It’s why we cling to the table like the life preserver it is: this is not news. When I eat Hungarian goulash and spaetzle, my maternal grandmother, Clara, is feeding it to me, and like always, she’s forgotten to take off her Persian lamb hat and is sweating over the stove; I’ve missed her every single minute of every day since she died in 1982, when I was in college. I cook her food; I keep her alive. When I make chicken soup and I strain it and strain it and strain it again the way my father’s mother, Bertha, did, I can hear her padding around in her house coat and slippers — the scuffed pearl ones that looked like ballet shoes — behind me in her Brooklyn kitchen, heaving open the heavy door of her ancient, bulbous Frigidaire, its vast metal handle wrapped around its fat waist like a girdle.

When you make the meatballs and gravy or apple strudel or chicken and dumplings or sausage and peppers or fried chicken or potato pierogi or whatever it is you associate with a particular person who has long since departed our carnal world, you bring them back from the dead. You taste their food, you catch a whiff of their Aqua-Net, you hear the shuffling of their heels on the linoleum; you close the gap not only between then and now, but heaven and earth, like the unintended, ghostly hum of pilots flying to Germany seventy-five years ago, fate unknown.

July 22, 2015

This is the work of life.

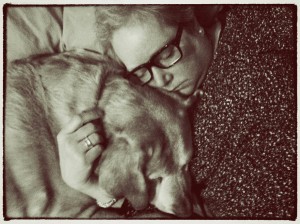

It was a gorgeous night — all peepers and frogs, and dry as a bone after two days hot and wet enough to melt glass — and I spent much of it sitting on our front porch with Addie, our [almost] fifteen-year-old Yellow Lab, who came to us at seven-years-old having been dumped by her people after a lifetime of churning out backyard puppies for sale. She moves slowly these days; she’s a quintessential velcro dog, attached to my hip by love and affection and the hope of additional kibble falling from the sky. On this particular night, Susan was on the train, on her way home from New York; Petey, our terrier, was on an overnight at doggie day camp to blow off some hysterical puppy steam. Addie and I sat together in the quiet, just looking; watching the sharp slant of the early evening summer sun on the garden. Older dogs do this: by their pace alone they force you to slow down, to pay attention, to lift your head to catch a brief cloud of honeysuckle and lilac passing by on the breeze.

When I got up to come into the house, Addie stood up with me and I held the storm door open for her; she waited for me to go in first, as if to say After you, but I ushered her in ahead of me. She and I are very formal that way, but she possesses both the age and the wisdom that, in my opinion, always goes first. I picked up her bowl, gave it a quick wash and added a cup of kibble, a dollop of mashed pumpkin to keep her ancient skids greased, and two pills: a square, brown anti-inflammatory for her hips, and a natural supplement which mimics the odious Prednisone she’s had to take from time to time. I mixed everything together and she stood watching me — she knows the stirring sound and the hand motion and what comes next — as I put the bowl down. She waited, looking me square in the eye and wagging, and I did what I always do right before she eats: I kissed her on the head and told her she’s a very good girl. She won’t eat unless I do this; I have no idea where the ritual comes from — perhaps her previous owners forced her to wait dutifully before she ate, as a way to wield some sort of power over her — but I’m glad to turn the act into something joyful and loving rather than controlling, and she’s glad to receive.

That night, after feeding Addie, I realized that I knew the exact size and shape of her pills, and that I could draw them in great detail if someone asked me to; I can tell you exactly how much pureed pumpkin attaches itself to the side of her bowl at every meal, and how it must be scrubbed out before I feed her again. I can describe the sound the kibble makes when it’s folded into the pumpkin (muffled, like pebbles on a trampoline), and the crinkle of the bag where her treats are kept. I can tell you about the face she makes after she’s eaten — the way her brown eyes change from inquisitive and hopeful to soft and loving — and that it’s exactly eight minutes from her taking a post-dinner biscuit to her hip-aching climb onto the sofa, where she spends half an hour licking a favorite pillow while she digests, keeping a watch on us for the rest of the evening until we all file down the hallway as a family, one-by-one, and get into our respective beds — humans in ours; dogs in theirs.

I can tell you all of this in exact and mind-numbing detail, but I cannot tell you the number of scoops of coffee I put into my Chemex every morning; I cannot tell you how differently the eggs from my neighbor’s Araucana chickens feel in my hand versus the ones that come from her Rhode Island Reds; I can’t tell you how long it takes ghee to melt in my late mother-in-law’s cast iron Griswold pan set over medium heat. I can’t tell you into which pepper mill I’ve put the Tellicherry peppercorns (my favorite) and in which pinch bowl the kosher salt is sitting. I make coffee and a hard-boiled egg for breakfast almost every morning; I saute something in hot ghee nearly every day, and I salt and pepper it. Which means that somewhere along the line, I’ve stopped paying attention to the most mundane activities — the daily work — of my life.

I could claim to be busy, so very busy, because, like most of us, I am, although probably no more than you. I’m writing a lot these days, finishing a manuscript and making notes for the one that will follow it. I just returned from a glorious week in Oregon at a writer’s workshop, and the loose ends and logistics I had to organize before leaving for the west coast nearly undid me: there were Uber apps to download and car services to arrange, manuscripts to be printed out, broken printers to curse at, keys and swipe cards that were not to be lost, and passwords to be remembered for my iCloud, my cell phone, my Skype account, my email accounts, my mother’s email account, my bank account, my Twitter feed, Instagram, and Facebook.

The last thing I could tell you is how one eggshell feels compared to another, or which pepper mill is holding which peppercorn. But I can tell you what Addie’s pills look like, and the sound her food makes when it hits the bowl, the softening of her eyes when the oxytocin starts to course through her body, and the rumbling, midnight snore that comes out of her like ujjayi breath.

It’s taken Addie to show me when I’m not paying attention to the routines of my life. And how, in a world that prizes exceptionalisim — the big, the fast, the overbooking and the overextension and the hyperconnection that short-circuits our analog human brain — it is the unremarkable and the quiet that we clandestinely crave, as if it were the most dangerous, threatening thing of all.

June 13, 2015

Little scraps of wisdom.

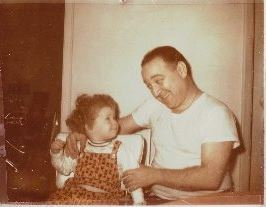

I believe that what we become depends on what our fathers teach us at odd moments, when they aren’t trying to teach us. We are formed by little scraps of wisdom. ~Umberto Eco

I have the metal strongbox, where he kept the hatband from his days as a Naval officer, that he let me play with as a child. I have two volumes of Slipstream, the books that he edited for the Navy. I have his wings; his flight diary documenting every nighttime run he made over the course of three years; his Naval aviator diploma from Corpus Christie dated 1944; his letters home from the Pacific; his fountain pen; his dog tags; his gold flight ring that he had turned into a charm for my mother’s bracelet. I have his leather-bound looseleaf notebook that he let me use in junior high school, and his Bar Mitzvah books from 1936 inscribed A Gift From Mr. & Mrs. M. Kastoff and Family that he gave to me when I moved out of his parents’ apartment, which he kept renting even though they’d been gone for years.

I have the ties I bought for him when I was studying at Cambridge; his gold Hamilton watch on its alligator band; his black plastic aviators from 1970; his English duffel coat that he had to have tailored because his arms were short; his leather flight jacket with his squadron patch and gold wings sewn onto the breast. I have his robin’s-egg blue metal home movie screen; his Super 8 editing viewer; his cans of home movies; his bags of birthday cards he sent to his mother from the time he was a boy; his clipping of a famous wayward cousin’s obituary, which he stored in a half-gallon zip lock bag.

I have his crates of albums from the 1950s: his modern jazz, his Moiseyev, his Mohammed El-Bakkar, his Moishe Oysher, his Chopin, his Mahler, his Lenny Bruce. I have his 1962 copy of Craig Claiborne’s New York Times Cookbook; his Dione Lucas; his 1958 Arabicaware; his Carol Stupell plates; his electric carving knife; his mother’s end table.

I have his picture of me just hours old; his picture of me the day of my cousin’s Bar Mitzvah; his picture of us having burgers at the Shalimar Diner in Forest Hills; his picture playing tennis with my stepmother, the love of his life. I have his picture on a horse at his dude ranch; his picture walking down the aisle at his own wedding; his picture at his ad agency. I have, sitting in my desk drawer, his brown leatherette wallet that he was carrying in his back pocket on the day of his accident; his dry-cleaning stub for clothes he would never pick up; his ticket for laundry he would never wear; his library books he would never read; his AARP membership he would never renew; his Amex card he would never use.

I have his sense of humor and his ferocious temper and his chuckle; his curly hair and his fair coloring, although not his blue eyes. I have his love of travel; dry gin Gibsons; radio storytelling; English history. I have his love of the American West; his hatred of Schoenberg; his appreciation of Danish Modern furniture, expensive German medium format cameras, good advertising, and Swiss fondue. I have his fondness for bluegrass; big dogs; San Francisco; northern New England; Iowa; Penobscot Bay; John Muir; Thoreau. I have his affection for roast pork; silvertip beef; fried chicken; remoulade; cold lobster; Schlitz; Mallomars.

I have his belief in the sanctity of cooking, and his love of feeding people.

I have his hands; his feet; his shoulders; his crooked smile; his easy teariness.

I hear his laugh; his cough; his snore; his shout. I hear him, always: over my shoulder in the kitchen; on the phone on a Sunday morning; next to me in the car; taking a practice swing while I’m teeing up.

My father’s been gone for thirteen years; he went out to run an errand, and he never came back. He lives now in my heart and my memory. In my house, I have the stuff of him, the scraps of him, but not him.

In my house, every day is Father’s Day.

April 21, 2015

On Earth Day Ennui

On April 22, 1970, I was seven years old. Mrs Kwartowitz, my first grade teacher, wore a brown suede poncho and hoop earrings big enough to shoot a basketball through. Her husband (Mr. Kwartowitz) looked a lot like Allen Ginsberg, and made it his job to tie-dye the jeans of every one of his wife’s students who provided him with a pair. (Gaga, my mother’s mother, thought it was a fabulous idea and ran to Alexander’s on Queens Boulevard, where she bought me a pair of Wrangler bell bottoms that were so stiff they stood up by themselves.) In preparation for the inaugural Earth Day celebration, which Mrs. Kwartowitz said was a very big deal, the entire first grade at P.S. 174 took up Save Mother Earth collections in little green UNESCO boxes; I have no recollection of where they were sent, only that mine was bursting at the seams like a small hippie Tzedekah box. Mrs. Watkins, a gorgeous Angela Davis-lookalike who taught the class next door to Mrs. Kwartowitz’s, showed us how to grow an avocado tree using an avocado pit and two toothpicks. But at home, my grandmother still used toxic Noxon on the silver; we drank Tab and Hawaiian Punch almost every day, and blithely tossed the empties out along with our voluminous industrial meat scraps down the incinerator shoot, which belched enormous black mushroom clouds of pollution into the sky above 98-05 67th Avenue. I begged my mother to get us some house plants — Mrs. Kwartowitz said they purified the air naturally — which she did: a Ficus tree that died when our Schnauzer repeatedly mistook it for a fire hydrant; and a Wandering Jew, which clung to life until the start of second grade, when my mother forgot to water it and it dried up like California.

Fast forward forty-five years and Earth Day (which seemed to be such a positive, tree-hugging thing to get people involved in back in 1970) sometimes feels depressing and aggravatingly futile, as if those of us who care about the planet are attempting to put out a forest fire with a thimble of water. I can’t quite remember who it was who first said that the planet is a living, breathing, sentient organism with a pulse and a temperature — like a hospital patient — and that if we essentially do to it what my Schnauzer did to my Ficus, it will die a protracted, painful death, which can be avoided (or at least slowed) by doing, among many, many others, two things: 1) Addressing in a serious way what appears to be the uniquely human propensity for entitlement on both the personal and public scale; and 2) Redirecting breathtakingly vast subsidies away from industrial monoculture and genetic modification geared to profit above all else, and pointing them instead toward food production and organic farming and permaculture practices that conserve resources, reduce water consumption, and ultimately, respect and heal the planet while feeding its inhabitants. This is an old, old story; point number 2 is self-evident. Point number 1 can best be described this way: We believe ourselves to be an entitled animal. We somehow feel a God-given right to manipulate everything and everyone around us, because we have thumbs and we have resources; if we don’t like it or it cramps our style or it doesn’t impact us directly, we change it or politicize it or kill it. Or, if we don’t want to discuss it at all, we simply pretend it doesn’t exist, like the elephant in the room: we’ll only talk about it if it serves our purpose, or if we want it for its tusks.

So, on the forty-fifth anniversary of my attempting to grow an avocado tree in a jar using toothpicks, I’m not feeling particularly sanguine about the health of the planet, or the inclination of its inhabitants to actually band together to do something about it. We’d rather argue and call each other names, which is often the most politically expedient thing to do, especially as we head into an election season here in the States.

My response has been decidedly more personal; over the last few months, I’ve taken to reading, listening to, and cooking from works that give me hope, energy, and no small amount of faith and stability when I find myself suffering from environmental ennui. To loosely paraphrase the great Terry Tempest Williams in her conversation with Krista Tippett, this is a time for people on opposite sides of the fence to sit down and figure out how to move forward together with the safety of the planet and our human community in mind.

Here are my greatest Earth Day inspirations:

To Listen

Terry Tempest Williams, On Being

Deborah Madison on Food Farmer Earth

Nikki Henderson at EdibleSchoolyard.org

Sharon Salzberg and Robert Thurman, On Being

To Read

Krista Tippett: Einstein’s God

Peter Matthiessen: The Snow Leopard

Wallace Stegner: Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs

Terry Tempest Williams: Finding Beauty in a Broken World

Terry Tempest Williams: When Women Were Birds

Gary Snyder: The Paris Review Interview

Gary Snyder: The Man in the Clearing

Mas Masumoto: Epitaph for a Peach

David Gessner: All That Remains

Barbara Kingsolver: High Tide in Tucson

Elizabeth Kolbert: Field Notes from a Catastrophe

Richard Payne: How Much Is Enough?

To Cook

Deborah Madison: Vegetable Literacy

Deborah Madison: Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone

Heidi Swanson: Super Natural Every Day

Viana La Place: The Unplugged Kitchen

Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall: The River Cottage Cookbook

Paul Bertolli: Cooking By Hand

Alice Waters: The Art of Simple Food

April 7, 2015

Infrequent Potatoes

I was a particularly tiny baby; my mother didn’t know that she was pregnant for six months (being unable to get her antique garnet ring off was a clue; she went to the doctor at her teenage niece’s suggestion) and the diagnosis sent her into a tailspin. In a shaky picture of my parents taken by my grandmother in Carl Schurz Park, the evidence is barely noticeable: there is my mother, the East River over her shoulder and Queens behind her in the distance, her wrists so slender and lithe even in her ninth month that her charm bracelet, heavy as Marley’s chain, would slide off her hand until she had a few links removed. There I am, the incontrovertible affirmation of her pregnancy, and nothing more than a minuscule bump under her pink and white cotton blouse. My mother carried me to term, almost to the day; I weighed four pounds at birth which, for scale, is more or less the size of an average supermarket chicken.

My mother at the Washington Square Park Art Fair, nine months pregnant. June, 1963.

The words my mother uses to describe me as an infant: spindly, delicate, tiny, petite, exquisite, dainty, fine-boned, wispy. Not being one to nurse — I would have wound up with a chest like your grandmother’s, she says — she fed me tiny amounts of formula, botching the instructions given to her by my first pediatrician at New York Hospital. I screamed all day and all night for my first three months, until our next door neighbor in Yorkville, a gorgeous German woman with a face like Marlene Dietrich, told my mother that I was probably hungry; she instructed her to fill my bottle with thinned-out oatmeal, cut an X in the nipple, and let me eat. She did, and at last, I stopped crying. I also ballooned up like a scaled-down version of The Michelin Man.

No longer the size of a chicken.

Eventually, the oatmeal weight fell off me: like most middle class American children of the Sixties and Seventies, I was fed a regular diet of meat, chicken, fish, lamb, and, because I was almost always anemic, beef liver, which looks surprisingly like beef liver. I shuddered at its jiggling, squidgy presence; my grandmother, who cooked most of our meals, broiled it until it took on the consistency of a stiff brown sponge, and my mother served it to me on our heavy burnt umber earthenware next to two flaccid spears of canned asparagus; there was no bread at our kitchen table, no rice, no pasta, and infrequent potatoes. My mother and I drank Tab by the bucketful, going through a six pack every two days. By the time I was four, I had become an unwitting adherent to something resembling The Atkins Diet; I was so skinny that my mother shook me into my school leotards like a pillow into a pillowcase. When I went into first grade, I carried damp tuna sandwiches made on Diet White bread, which disintegrated into a dense brick of bleached mush that curled itself around my red plaid thermos like the letter C by the time I arrived at school.

As I wrote in Poor Man’s Feast, when my mother went off to have her hair done every Saturday, my father — not someone I would call corpulent, but certainly not thin — secreted me away for fancy lunches that were as enlightening as they were forbidden: I learned what happens when you apply a coating of egg and flour to trout, saute it in hot butter and bathe it in wine and lemon juice. I learned what happens when you slice potatoes to a thin film, layer them in a shallow copper dish, and blanket them in cream. I learned what happens when you roll a crepe around warm apricot preserves and dust it with confectioner’s sugar and chopped hazelnuts. And I learned to keep my mouth shut once I got home, because food was the enemy of the body.

My mother went back to work when I was eleven; my grandmother stepped in after school and fed me regular grilled cheese and bacon sandwiches, potato latkes, pizza, and, because she loved him, Arthur Treacher’s fish and chips. All that food fueled my raging tennis addiction; I played it every day, for hours. My mother never noticed what I was eating because my grandmother chose not to tell her, but also because all that tennis turned my skin and bones into solid muscle. I became a swimmer and my shoulders broadened; I hit puberty and the chest that kept my mother from nursing me as an infant was suddenly mine. My mother’s desperate, hysterical need for thinness, achieved by starving her teenage self in order to be the model and television singer she eventually became, was a blip on my genetic screen. My body rebelled in the most profound of ways: I was no longer skinny. As a teenager, I began to resemble almost every woman on my father’s side of the family: thick-boned, solid, muscular, and zaftig enough to acquaint me with the bitter flavor of self-consciousness.

“You’ll lose that chest if you drop some weight,” my mother said when I started college, as though That Chest was a disembodied entity unto itself, with a mind and government all its own, like Texas. At school, the freshman fifteen worked the other way for me: with everyone gorging themselves on pizza and East West lasagna at the cafeteria, I ate nothing but taco-flavored Doritos and Diet Coke in my dorm room, but only when my roommate wasn’t around. I came home that October, fifteen pounds lighter.

My mother was confused and irate a few years later, when I went to work for Dean & Deluca, and attended cooking school at night: I wanted food in my life. I wanted to understand sustenance, and to find that almost spiritual connection that comes from feeding your self, and others, thoughtfully and well. I wanted to recreate a family table of goodness and peace, where food was not the devil, and it didn’t have to be hidden.

My body responded to the stress of her furious consternation with uncanny irony: surrounded as I was by masses of food every day and night, the pounds cascaded off me without my even trying to lose them. My nails went brittle and my hair thinned, and then fell out. My thyroid was off kilter and my heart rhythm wonky and I passed out twice — once in the walk-in, once on the loading dock while signing for a Sid Wainer delivery — but man, did my body look great: my fat jeans were a size two, my everyday pair, a zero.

“Okay,” she said, as though I was competitively orchestrating my weight loss, “you win. You can stop now.”

Over the years, my body has settled like a house; the Title Nine catalog invariably arrives when I’m feeling sluggish and thick. My knees and hips creak, and I have a bottle of Aleve in every bag. No matter what — no matter how many steps I take, no matter how dedicated to my FitBit I am, no matter how much yoga I do, no matter how often I go to the gym, no matter how much I cut out wine or sugar or infrequent potatoes — my weight travels along a five pound continuum: sometimes I’m up, sometimes I’m down. Like my mother when she was pregnant, I gauge change by how tight my rings are. On the days when I can’t get them off, I don’t go to see her; I don’t tell her why.

Recently, she came to stay for Passover and Easter; I saved my beloved matzo brei — the crack cocaine of my people, which I make once a year — for the breakfast after our seder. That morning, we sat at my dining room table while she drank a cup of hot water and watched me lift my fork to my mouth; she glared violently at it, and me, like we were the devil incarnate. I pushed myself away from the table and took my plate into the kitchen; I stood at the sink and ate with my back to her, hidden from view.