Elissa Altman's Blog

June 13, 2022

Poor Man’s Feast has moved!

Please visit PoorMansFeast.substack.com to continue reading……

March 19, 2020

On Nurturing Your Heart in Uncertain Times

A note from the author of Poor Man’s Feast

Hello friends.

It’s been a very long time since I’ve written here, and a lot has happened over the last year: Motherland was published in both hardcover and audio by Ballantine Books and PRH Audio. I went on a book tour, and spoke with many people — sons of NPD fathers; daughters of NPD mothers — about what it means to become the inadvertent caregiver for a senior parent with whom one has had a traumatic relationship. I recently learned that Motherland was nominated for a 2020 Lambda Literary Award, which is thrilling. Last summer, I began teaching a memoir workshop for Fine Arts Work Center both on site in Provincetown, and online, during the rest of the year. I’ve also started work on some new and important projects, including stepping back into my longtime role as an editor, this time for the wonderful (literature-loving, author-supporting) Zibby Owens of Mom’s Don’t Have Time to Read Books. Susan is about to begin her sixteenth year as a senior book designer for Random House, designing interiors for authors ranging from Ruth Reichl to Jodi Picoult. People have moved in and out of our lives in breathtaking, often astonishing ways; we’ve experienced the premature death of our dear friend Kurt Michael Friese, withering illness among other friends, and ghosting where people we’ve opened our hearts and home to literally just up and left mid-sentence, as though friendships in the digital age are, as my grandmother would have said, easy come, easy go, and fleeting as a Tinder swipe.

Susan and I just celebrated our twentieth anniversary together. Our lives are, for the most part, good and safe and filled with love and the bizarre gift of clarity that is the B side to trial. And the sense that, perhaps, most of us don’t really grasp how fleeting time is, and how the stolid weight of true affection — unflappable and dare I say kind (that word is tossed around today like a tumbleweed in a windstorm) — cannot be measured in clicks and downloads and followers, but in how readily we are able to forgive the vagaries of our own humanity rather than just simply walk away. And how we help shore up each other’s hearts.

I am sitting in my office today. My little New England street is quiet, on an unofficial quarantine thanks to the coronavirus. As a child of the seventies, I grew up watching movies on big screens and small about viruses run amok. I was always certain that the powers that be would keep us ahead of the game. That was until the mid-1980s, when AIDS ravaged my group of friends and the industries in which I worked at the time (food and publishing); it took a full ten years from the time that my first friend died while I was in college to the time a cocktail was developed and released to the public. The medical world did not move fast enough; patients were expendable pariahs. And so it is personally very hard and complicated for me to put my head down and walk into the powerful wind that is the coronavirus, having been down the virus road before. But I have to.

Most of us, regardless of background, political stripe, or sensibility, are not MeFirsters. I believe that most people actively want to help others; the human condition is to reach out a hand. What can I do to help is a sentence I have heard in the last few weeks perhaps more than ever before. We are all exhausted from the politics that have plagued us, and while a deadly virus is certainly no way for a population to come together, it has had that impact in many places. As for the many heroes among us: they are neither loud nor self-aggrandizing, and their stories often go untold. And gone are the days when we will wait around for a cure; gone are the days where we will allow it to take a decade.

I’m a writer. It’s what I do; it’s who and what I am. I’m also a teacher, and a feeder. The first book I wrote, in the early 2000s, was a practical cookbook designed to help people who bought food in bulk not waste it. In the coming weeks — hopefully much sooner than later — I will be re-issuing it, and making it available digitally, for free, for anyone who wants it. Because waste is not an option: not for ourselves, our families, or our communities. We have to feed ourselves and the people around us.

These are uncertain, scary times, and we are now being called upon to do the right things. I believe we will.

Thanks so much for reading. Please come back soon.

March 6, 2019

Motherland is coming from Ballantine Books on 8/6!

Coming in August from Ballantine Books

Coming in August from Ballantine Books

All over my office: pictures.

Stacks, everywhere.

On a cold night in 2017, I carried out of my mother’s apartment an old brown and gold vinyl club bag — the kind one might bring to the gym in 1976 — filled with curling photos, papers, report cards, publicity clippings (hers), letters home from camp (mine). I don’t know when she had done this — methodically stuffed the bag full of the detritus of our life — but she had, and when it could hold nothing else, she zipped it closed and shoved it into the back of the closet in the den where after college graduation I had slept on a bad pullout sofa for two years until my doctor, alarmed by my blood pressure and the regularity of my burst ocular blood vessels, wrote me a prescription that said MOVE OUT.

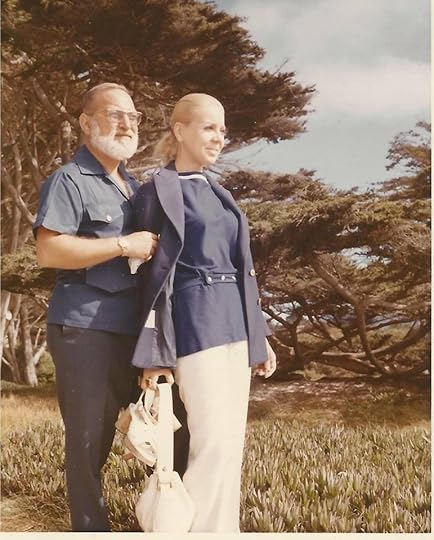

The bag had become a filing cabinet of sorts, and over the last few years, I spent hours and days pouring over its contents, trying to create some kind of order: photos from the sixties and seventies in one pile, crayon drawings in another, letters back and forth in another. I was trying to make sense of us through a taxonomy of our lives, mother and daughter, middle class, comfortable: the former, a professional television singer and model, so glamorous she nearly shimmered, addicted to makeup, suffering from Narcissistic Personality Disorder. The latter, different, reserved, the opposite in every manner of the woman who bore and raised her. The images were familiar: mother and daughter posed on the marble steps at Caesar’s Palace in 1970. The mother poured into a slender black sheath on a Saturday night in 1965. Mother and father amidst the scrub pine in Big Sur, in a stunning photo taken by their seven-year-old daughter with her father’s heavy medium format camera. 1970.

Here, he said: Point the camera, and squeeze the trigger.

My father and mother, Big Sur, 1970.

My father and mother, Big Sur, 1970.In 1974, the pictures suddenly stop.

The letters back and forth stop.

The drawings and the postcards stop.

What happened to us?

What had I been looking for in the bag? What story was I trying to piece together? When did my life with my mother — my beautiful, tempestuous, addicted mother — begin to shred into pieces? Attempting to apply order to chaos is what storytellers do; it is why we are here. To make sense of the narrative of our lives and the lives of others. When my mother suffered a catastrophic fall in 2016 that required my return to her side — I had fled our codependent life nearly twenty years earlier — the roles reversed. With my mother, now in her eighties, and me faced with being her caregiver after more than half a century of enmity and fury, I wanted to understand exactly who we were. How we got to this place.

I wanted to know whether or not healing would ever be possible.

With more than 43 million Americans, most of them women, now in the role of inadvertent caregiver to a parent — half of those parents are mothers — a vast number of us are stumbling around in the dark, not only finding our way through the morass of caregiving bureaucracy for which there exists no instruction book and even less money, but also faced with the unthinkable yet karmically inevitable: taking care of an older parent with whom our relationship has been, as they say, complicated.

Motherland is my story and also the story of millions: the universal mother/daughter conundrum that defines who we are as women, as daughters, as mothers.

Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing, is now available for preorder wherever you buy your books:

Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Indiebound

June 11, 2018

Join me for Writing Your Story, Feeding Your Soul

Ten years ago, when I launched Poor Man’s Feast, I could not have dreamt the places it would take me; since 2008, there have been two memoirs with (mostly) food at their core and, coming in 2019, a third, the catalyst of which was a yearlong column I wrote for the Washington Post. I have traveled from the Balsamico Tradizionale cellars of Emilia Romagna to the salmon farms of Tromso, Norway, four hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle. I have ghostwritten a celebrity cookbook (not telling, then I wouldn’t be a ghost), acquired and edited scores of others, and become an adopted member of the Edible Communities consortium of hyperlocal food magazines. I have spoken about the language of food — its poetry, its magic, and its place in our culture — alongside some of my heroes, including Molly O’Neill and Carolyn Forche. I have taught the craft of narrative food writing in Ireland at Lens & Larder with my dear friend Diana Henry, and at the Loft Literary Center the day after an election that would push the world off its axis and send many of us scrambling for comfort. I have spent much of the last decade immersed in a rapidly changing food culture, one that is inextricably bound up with politics, war, celebrity, scandal, and heartbreak. It is a world that is simultaneously nurturing and utterly withering.

Over time, how I talk about the narrative of food and this mundane act of creating sustenance has taken a turn for the contemplative. I believe that feeding oneself and others is an inherently meditative and spiritual practice that extends far beyond the confines of the hottest new restaurants, the edgiest new chefs, the trendiest new techniques, the most stunning new kitchens. This is not a revelation: watch the opening scenes of Il Postino, and see Massimo Troisi slurp a bowl of soup with his father, and know that you are witnessing a true poor man’s feast. Read the story of La Cocina, a San Francisco not-for-profit food business incubator for low income, largely immigrant women and the impetus behind Refuge, a storytelling project focusing on the role of food during times of crisis, war, loneliness; this is an idea born of hope, history, and sustenance.

Wherever I’ve traveled and to whomever I’ve spoken over the last ten years has brought me to the understanding that humans are naturally drawn to what the late food writer Marion Cunningham called The Modern Tribal Fire. The quality of the food itself is important, but it’s not the focus here; that’s reserved for the sharing of table stories — the storytelling that goes on around the place of nurturing. Table stories bind us together in joy and sorrow. They are the human connective tissue possessed of the quiet power to transcend politics, war, religion, socioeconomics, family dynamic. Table stories can be meditative, therapeutic, heart-filling. They form the basis of our individual narratives of sustenance and nurturing that extend beyond the walls of our homes and deep into our communities. Table stories make us who we are: each one of us, regardless of our background, can write, share, contemplate them.

Many of you have reached out to ask me about upcoming writing programs that marry contemplative practice to the personal narrative of sustenance. I am delighted to announce that this November, after Thanksgiving, I will be launching my program, Writing Your Story, Feeding Your Soul, at the beautiful 1440 Multiversity, located in the Santa Cruz mountains amidst the majestic redwoods. Together, during a two-day post-holiday retreat, we will break bread, read, write, and examine the stories we tell around the table, and how our modern tribal fire connects our past to our present, to inform the way we think about nurturing and sustaining ourselves, our families, and our communities. While this will be a generative food-related writing workshop, it will require no prior experience beyond the willingness to recognize the healing nature of sustenance and storytelling. Yoga and meditation will be included, as will delicious meals created by the amazing Chef Kenny Woods of 1440. Some scholarships will be available.

Please join me. For more information, feel free to contact me at Elissa@Poormansfeast.com, and at

Writing Your Story, Feeding Your Soul

February 24, 2018

join me and Diana Henry at Glin Castle in Ireland, for a springtime writing retreat

“I’ve always associated the moment of writing with a moment of lift, of joy, of unexpected reward.”

Look at the image; inhale.

Smell the damp Irish springtime grass.

This is stunning Glin Castle, where I’ll be teaching the art of narrative food writing, memoir, and essay alongside the legendary Diana Henry, one of my favorite writers of all time, food or otherwise. The retreat runs from April 13th through April 16th 2018, and includes Irish breakfasts, dinners, and of course, trips to the pub, which are actually not only on our agenda, but are mandatory. The location is breathtaking, and the accommodation is as spectacular as this picture would suggest (click over to the Glin Castle website for more images).

Diana and I will teach separately and together over the three days, and will engage with all attendees not only as a group, but individually. Please join us for what is sure to be a beautiful, memorable, creatively generative writing retreat.

For more details and to hold your spot, visit:

http://www.lensandlarder.com/home/

Join us. We look forward to seeing you in Ireland.

December 2, 2017

motherland 2.0

We were no longer cautious about our conversations. The rules about what a doctor can say to an adult daughter whose older mother is not taking care of herself can be bent when that mother is in danger.

She will fall, her doctor told me almost two years ago, and it will be bad.

I tried to believe that if only she ate what I fed her — she has a horrible relationship with food and always has; I wrote a years-worth of columns for the Washington Post and gave a TEDx talk about it— my mother would stay healthy and young and vital. She would be safe. Forget the laws of probability.

I tried to pretend that if she remained as remarkably beautiful as she is, as she has always been, my mother would never be at risk. Beauty, I was sure, would protect her from the inevitability of time.

One day a few months before the accident, I walked behind her on Madison Avenue to watch how the pose she has stood in her entire modeling life, coupled with atrocious nutrition, had taken a toll on her body: her left foot was pointed out so hard that her ankle was rolled to near-disjoint. She stopped to look in the window at Chopard; twenty years earlier, she owned one of their signature watches–the kind that has a few tiny diamonds free-floating beneath the crystal. Over the course of two months, she exchanged it five times, each time for a different color face and strap; I often accompanied her. Eventually, the clerks stopped buzzing her in, which enraged her to where she’d stand in front of the glass door, glare at them ignoring her on the other side, and not move.

I tried to explain why they wouldn’t let her in anymore — that she couldn’t keep returning the watches over and over again. It reflected her entitlement, and her addictive need to make her life better with things. But nothing was ever good enough — even with the watches she was still the same person with the same life and the same problems — so she returned them over and over again, as if each new color might make her happier and safer than the last one. They were expensive; she felt it was her prerogative; I tried to understand. Standing in front of the shop window more than twenty years later, she seemed wistful; she stared at the display and shook her head, her shoulders sunken with grief. I gazed down at her ankle. I was once romantically aligned with a modern dancer who didn’t make it into Twyla Tharpe‘s company because her turnout wasn’t good enough; my mother could have been Twyla’s principal. When the fall came, it would splinter all of those delicate ankle bones like wooden matchsticks. Even beauty and fashion and Chopard watches with the little diamonds floating on their faces couldn’t stop time.

A year ago tonight, I was finally home from a long book tour for Treyf, my memoir of growing up in 1970s New York, in an assimilated, deeply quirky family that was always on the outside looking in. My last stop had been an overnight in California and a reading at one of my favorite bookstores. I was home less than twenty-four hours later. I dropped my bags in the entry way of our house, and Susan and I sat on the couch, exhausted. We went out to buy our Christmas tree, and we set it up in its cheerful red cast iron stand. We reheated frozen beef stew. We opened up a bottle of decent Pinot Noir. We listened to the radio as we do every Saturday night, our dog curled up between us. The phone rang: two hours away, my mother had gotten up from watching television, her foot was asleep, and her ankle exploded beneath her. There would be no going back to the way life had been before, for either of us. No amount of fashion or makeup or diamond watches or herb-stuffed organic roast chickens made by me with love and tenderness could protect her.

Over this last year, there have been two surgeries, forty days in a rehab facility, one consultant, three caregivers, two attorneys, four longterm care managers. There was the fight about the grab bars, the fight about the walker, the fight about the money, the fight about the insurance, the fight about the cane (which she carries tucked under her arm, like Peter Boyle dancing to Puttin’ on the Ritz in Young Frankenstein), the fight about the proper medication prescribed by two different doctors for the osteoporosis she doesn’t believe she has, the fight about the personal emergency alert system because one of her man friends who is younger than my wife doesn’t like them. My mother’s filing system involves gigantic white plastic garment shopping bags strewn all over her apartment, so it took me weeks to find her personal documents, which were dog-earred and stuffed between the pages of a Playbill for the 1995 Broadway stage revival of Sunset Boulevard starring Glenn Close in her first role as Norma Desmond.

I live two hours away from her, so we speak on the phone at least once a day; my heart stops when I hear her voice, until I know that she’s safe, until I know that she isn’t raging about one thing or another. My hands shake when her name comes up on my caller ID, or when she calls my cell and if she can’t reach me, Susan’s. I haven’t been sleeping well this last week — no amount of Sleepytime Tea or meditation or booze will help. (As if.)

A year ago tonight.

I’m not a Christian woman, but I know that Advent begins tomorrow. I’m reminded of the great old Anne Lamott piece, which I first read in 1997 when it appeared in Salon, back around the time my mother was fighting with strangers about diamonds.

Broken things have been on my mind as the year lurches to an end, because

so much broke and broke down this year in my life, and in the lives of the people

I love. Lives broke, hearts broke, health broke, minds broke. On the first

Sunday of Advent our preacher, Veronica, said that this is life’s nature, that

lives and hearts get broken, those of people we love, those of people we’ll

never meet. She said the world sometimes feels like the waiting room of the

emergency ward, and that we, who are more or less OK for now, need to take

the tenderest possible care of the more wounded people in the waiting room,

until the healer comes. You sit with people, she said, you bring them juice

and graham crackers.

Every day living with a senior person is like opening the little door on an Advent calendar; what will we be faced with? What is behind door number one? Love, grief, fear, anger, health? A good day? A bad day? My mother would hope for her old Chopard watch with the little diamonds floating beneath the crystal, now long gone (I can’t remember which one she finally settled on; ensnared in fury and rage, she rarely wore it).

All I’d like is peace, and maybe a cookie.

October 25, 2017

poor man’s feast at eight.

My office was in the windowless basement of an asbestos-lined, faux-Georgian building outside Manhattan when I first began thinking about launching Poor Man’s Feast. Skull-and-crossbone construction signs were taped to locked interior stairwell doors, and more than once I became trapped between floors on my way to or from a meeting and had to wait to be sprung by someone — a chair-throwing art director; a sales manager and mother of a three year old little girl with a voice like Al Pacino — so that I wouldn’t have to sleep there overnight. Our work area was commonly referred to as The Morgue, and not long after starting there, I began to resemble the Tom Hanks character in Joe Versus the Volcano.

Eventually, I began to look elsewhere for employment, and came close to being offered a job with a Manhattan cookbook publisher (I’ve moonlighted as a cookbook editor for years). But there was a problem. Actually, two.

The woman who got it, a colleague said, has a blog. And you don’t. Also, she has more, well— you know— energy.

So I went back to my little office-in-the-morgue, and, having discovered that I could finish a week’s worth of work in two days, closed my door and launched Poor Man’s Feast. Initially, it was meant to be a daily publication (see energy, above), and a place where readers could go to find a simple, easy, delicious recipe that would cost them very little. The food I wrote about would always have context — a story; some history; connection to place and person and time — but the focus of the writing would be primarily on the recipe. It sounded like a good idea.

It’ll never work, my colleague said. It’s the word POOR. Nobody likes the word POOR.

It was getting to be Thanksgiving, I had a few days off, and I gave the whole business some serious thought. And then I broke the rules: in my heart of hearts, I knew this colleague was wrong. Susan, who is a book designer, cobbled together the banner from a sixteenth century, public domain butcher’s advertisement, and added the type. My artist cousin Mishka Jaeger helped me set it up. We worried about offending some of my friends and family who don’t eat pork. Then there were the vegetarians and the vegans who would run screaming into the night when they saw the pig.

Just write the first post, Susan said, and we’ll go from there.

It was me or the asbestos.

After a few months, Poor Man’s Feast began to take on a life of its own; there were snarky, snappy, wink-wink/nod-nod posts about parsimony, pantry-stocking, the eating of squirrel, and a cooking smackdown between two New York Times food writers. 1970s porn star Ron Jeremy showed up in a post subtitled Member’s Only Dining. There were interviews with Maira Kalman, Deborah Madison, Andrew Zimmern, Joan Nathan, Tamar Adler, and Dorie Greenspan, who talked about burning down her parents’ Brooklyn kitchen as a child. I wrote about an addictive knoepfli dish produced by a Seattle woman of Swiss-Chinese lineage, who left us much too soon. There was the realization why Americans think of eating vegetables as a chore, and what to do about it. There was a wedding at Buvette, two James Beard Award finalist nominations and a win, an earthquake, a story of breakfast eaten in anger, an essay on the ghosts that reside at one’s table, a piece about losing family and the healing power of light, an imaginary letter to Elizabeth David, eggs and aging mothers, midnight cooking after a day of traveling, varying attempts at faddish diets, forgetting how to cook for a brief time, two memoirs (this and this) and a new one coming in 2019 from Ballantine Books, many externally-published articles and essays in places including The Guardian and The Washington Post, and the most-read piece on the blog since it’s inception: an admission that, like many [many] food writers, my off button sometimes gets stuck in the on position where wine is concerned.

Along the way, there has been, I hope, a growing up of sorts that has resulted in a shelving of culinary snark, replaced with a focus on balance and substance rather than trend; a dedication to the craft and practice of writing about what sustains us, whoever we are and wherever we live, both at the table and far beyond. Over these last eight years, I’ve met remarkable people — food producers and farmers, cookbook authors and bloggers, novelists and poets and memoirists and essayists, artists and editors, photographers and multi-job-holding single mothers who manage to get a meal on the table for their children every night without fail. It’s been a learning process for me, and it has been enlightening; I gravitate now to food as history, nurturing, economy, politics, and sustenance, rather than entertainment. My readers —- you — who found me eight years ago and have stuck with me have taught me more than anyone else: about the importance of humanity and kindness and authenticity, and I’m forever grateful to you.

My employment at Asbestos Central ended after about three years, when the company liquidated my department and the local branch of the EPA eventually showed up in hazmat suits and shut down the building. My colleagues weepily packed up their boxes and clogged the hallways, asking each other if they were surprised, and what was next for them. Thanks to Poor Man’s Feast — the blog that I was told would never fly because the word poor was in the title — I was leaving the next day for Emilia-Romagna, on a trip to meet old-school producers of Parmigiana Reggiano, balsamico tradizionale, and Proscuitto di Parma with writers Rowan Jacobsen and Kim Sunee. While we were there, we learned the process of making culatello — literally, the little ass of the pig — which is salted, stuffed into its own bladder, hung, and aged in humid, 500-year-old caves.

The poor of this area have been eating it since the time of Caesar, I was told. They saved everything they could and made beauty and flavor against the odds.

That is food, but it’s also life.

And if it’s the definition of poor, I’ll take it.

A note to readers:

PoorMansFeast.com is re-launching in the coming months at this URL. Until then, this version will remain live, and I will continue to engage with all commenters, as always.

Many grateful thanks for your continued support and readership.

July 22, 2017

on waking early in the summer

Deep in the summer, when Susan’s schedule changes — she works longer days but spends every other Friday at home — the alarm clock goes off earlier than usual. The dog is still asleep, the cats are still asleep, I’m still asleep. A splash of pre-dawn light filters through the window over my dresser. For a long time, I rolled over and went back to sleep, but lately, I’m getting up with her, which is not like me. It’s five in the morning and I hate five in the morning, especially if I’ve slept fitfully, which I often do when I’m in the throes of anxiety or the after-effects of excess. (This is usually an attempt to stave off the aforementioned anxiety and frankly never works. Fuel on fire.)

Lately, I find myself looking forward to these early mornings. Most days I lay in bed and read — actual books of the actual paper variety — until seven or so, and then I get up to feed the wild hordes and walk Petey around the block. I make myself a cup of coffee and sometimes a hard-boiled egg, I check my email and try not to get sucked down the wormhole that is Facebook, and then I get down to work: I re-read the previous days writing and pray that it propels me forward which, if the stars are aligned, it sometimes does.

I’ve been reading a lot of morning poetry lately, before I’m even upright, drawing from a stack next to my bed: Mary Oliver, Marie Howe, Hafiz, Jane Kenyon, Donald Hall, Jane Hirshfield, and always, Mark Doty, who many years ago showed me that the line between exquisite prose and poetry was gossamer. I picked up Heaven’s Coast after two of my best friends, a couple, died of AIDs within a year of each other in the early 1990s, leaving everyone who knew them staring into an abyss, broken and wordless. I watched Peter and Tim — kind men and practiced meditators who, every day at their country cottage rose before the sun to sip tea in their garden — shrink and fade into vague glimmers of themselves, aging before my eyes as their lives became a litany of cocktails and T-cell counts and hospital visits. One by one, their friends began to die, their beautiful upstate New York weekend houses in bucolic places like Saugerties and Mount Tremper sloughing off cherished possessions like skin. Couches, dressers, dining room tables were passed around until there was nobody left to pass them to; estate sales and auctions turned up familiar place settings, and first edition leatherbounds that might have been read three years earlier in front of a fireside dinner party. I have pictures of Tim in my first Manhattan walkup apartment from the years before he and Peter got sick, ebullient and beaming over a blue and white Conran’s planter that I bought for his birthday, which he used strictly to grow Genovese basil on his Chelsea windowsill. And I have his last Christmas gift to me: a small wall sculpture in the shape of an angel.

So I clung to Heaven’s Coast like a blanket, and I let its words and its sorrow fill my ears and knit my heart back together. This is what good writing does; it’s a balm for grief. And when Susan and I were still in the earliest phase of our relationship — she had just gone through a breakup and we were emailing but hadn’t yet met (although we had first set eyes on each other in Central Park in 1986 back when we were mere children in our twenties and thirties) — and she told me that she was spending a lot of time in the early mornings sitting in her kitchen reading Donald Hall’s Without, that was it for me. That was all it took.

It’s been a very noisy few months here, filled with the clatter of uncertainty, of not knowing: my mother’s accident and her sudden need for eldercare; my cancer scare; politics so loud and unhinging that steadying myself has become a full-time job; writing my next book, which actually is my full-time job. So the need for quiet, for an anchor, for psychic ballast, is ever-present in my home. Waking early before dawn to read poetry grounds me like almost nothing else except, perhaps, cooking. It’s a genetic thing: when my grandmother died and my mother cleaned her apartment out, she found Gaga’s Complete Poems of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, copyright 1915, its spine shattered and held in place with silver gaffing tape. When she couldn’t sleep, my grandmother paced her Queens living room from one end to the other while reciting Evangeline mostly from memory until the sky turned red, the book clutched in her hands.

Getting up before the day is what she used to call it. Waking before the noise, windows open, sweetness in the air, up before the din. It’s soothing and restorative to hear good sounds; like poetry, it’s music to my ears.

Tim’s Pesto

Admittedly, the world does not need another pesto recipe. This is the first one I ever made and it is good, if elemental. Tim and Peter were vegetarians and ate this tossed with pasta, as one does. When they weren’t looking, I often left out the cheese, thinned it out with a little water, and drizzled it over hard-cooked eggs or the freshest white fish I could find — Halibut or Black Sea Bass — which I still do today, all these years later.

1 large bunch (2 heaping cups) Genovese basil leaves, washed and patted dry

2 cloves garlic

1/3 cup pine nuts (or 1/4 cup walnut meats)

1/2 cup extra virgin olive oil, plus more for storing, if necessary

Salt and pepper, to taste

1/3 cup freshly grated Parmigiana Reggiano

In a food processor or blender, blitz together the basil leaves, garlic, and pine nuts until coarsely chopped. With the motor running, drizzle in the olive oil and continue to process until smooth. Taste and correct the seasoning, and add the cheese. Continue to pulse until smooth. To store, place in a lidded container and top with a slick of more oil.

June 19, 2017

cleaning the house, tending the weeds.

We have been living here for thirteen years. It sometimes seems like we just moved in; other times it feels like we’ve been here forever. Four books written by me, hundreds of books designed by Susan, roughly eighty books edited by me. Three dogs, seven cats, although thankfully not all at once. Over the years, we have lost all of Susan’s aunts (there were five when I joined the family in 2000, out of a total of eleven siblings), her Uncle Bob, her mother, my father, who passed two years before we arrived here from Litchfield, and my cousin Harris, who died in 2008. Between our younger cousins, nine babies have been born, four on my side; we have met all but one of them, a handsome blond boy who was named for my father. Early on in our time here, we considered having children of our own, and for reasons both biological and not, we didn’t.

In the evenings, we look across the table at each other; we have gotten a little heavier and a bit grayer. We earnestly, often frenetically, try different diets: Mediterranean, Whole 30, Paleo. We drink less: only on the weekend, or Saturday night, or Friday and Saturday night. Sometimes we succeed; sometimes we don’t. We have accumulated: too many pounds, too much stuff, too many things. We have skinny jeans, fat jeans, the hiking clothes we never wear because we never go hiking, six pair of golf shoes, two sets of clubs, (piles and piles of) books, small appliances (a soda maker, a spiralizer), half a dozen sets of wedding china for twelve from the aforementioned aunts, two sets of silver, thirty-two knives that used to hang off a magnetic strip under the pot rack that holds a dozen or so pans from my life as a professional food person (whatever that means), twenty-seven red-striped cotton Ikea towels that we have stockpiled over a decade, handmade patchouli goat-milk soaps that spawn like bunnies under the bathroom sink, a plastic crate of expired medications for long-healed illnesses, old computer equipment including three non-working printers, my father’s SX-70 cameras for which film is no longer available, my uncle’s pristine Yashica-Mat twin-lens reflex for which film is available, a 1927 Underwood typewriter originally belonging to Susan’s Uncle George, a 1939 Remington Noiseless that had been my Uncle Marvin’s high school graduation gift from his parents and passed along to me by one of his daughters, to whom I no longer speak.

There have been thousands of meals cooked in a kitchen that is still a work in progress. Hundreds of bottles of wine have been consumed, ranging from expensive Bordeaux opened for a birthday celebration to the cheap plonk that my grandmother would have Germanized as pishwasser. I remember only a handful of the good ones; they have retained their importance by connection to an event or to the people with whom we drank them. For years, we saved the corks in a massive green glass jar, as if someday, in our dotage, we might sit down of a quiet evening and review them the way one might look through a photo album: This was the Bandol that we had with Lisa. This was the Brunello that we drank with Porter. This was the Sauternes that we had with Gale. Recently, we discarded the jar and its contents when we realized that the memories were more important than the corks, which were just another thing to keep, although at one point, we did consider making a trivet from the better ones.

We have an issue with things in this house; I attribute it in part to being adult-only-children-without-children (AOCWC), and to the fact that over the last few years we have lost so many people that it sometimes feels incomprehensible.

A small, personal holocaust, a friend of mine once said. You woke up and they were suddenly gone, taken away in the middle of the night. And so, without siblings in whose faces we might see our pasts, and without children who reflect back to us ourselves and our future, we cling to the representational, the inanimate, the stuff to which we attach memory and meaning.

But there comes a point when this detritus of life begins to pile up; it becomes dangerous. The accretion of things makes it impossible to walk a straight line, to put anything away, to see anything else but history.

Did you just move in, a contractor asked me the other day when he had to check our water tank. When I told him how long we were here, he seemed alarmed.

To be clear: we do not have a Collyer Brothers problem. But when I went downstairs to our basement a few nights ago to get something out of our freezer and found myself face to face with a small, gray nylon sack — the sort a rock climber might use for chalk; I’d never seen it before — filled with ancient pottery chips purloined by Susan’s ex on a southwestern camping trip twenty-five years ago, my heart stopped. A familiar, cold clamp of anxiety seized the back of my neck: I could instantly recall how I felt when this woman threatened our relationship when it was in its infancy. I could actually feel my slightly nauseous response to the every-Saturday-night-at-eight phone calls from long ago; the moments when I’d see her name come up in my email with a coy Hello darlin’ in the subject line; the promise to me that she would never, ever leave us alone, even though she and Susan had broken up years earlier.

It’s just a thing, Susan said, when she saw my face. I’ll get rid of it.

By why do you even have it, I asked. Why is it still here?

Susan pointed around the basement.

Why is any of this stuff still here?

There was my father’s blue metal screen on which he last showed home movies at our house party in 1971, before he knew that his best friend, drinking Scotch in the kitchen with my mother and a neighbor, was driving me alone to an abandoned park every day after school; there was a dust-caked, roll-top cassette case, holding the Memorex tapes of upstate New York shamanic healings that my ex and I made for each other in the 80s; there was a Jack Kramer Pro Staff wooden tennis racquet with a peeling pink gauze grip that, when I picked it up and inhaled, smelled like sweat and Dentyne and the hot clay I kicked up on the courts at Milton Academy, where I played the summer I was sixteen.

Piles of shopping bags sit everywhere: here are framed photographs of my father’s family, that lined the entry way to my studio apartment in Manhattan, where I lived for nine years. When you walked into the foyer, they were the first things you saw: This is my family, the wall said. This is my blood. I am not alone. Stacks of Susan’s family photos are piled up on our old couch between the oil burner and the washing machine: the aunts are still alive in those pictures — Ethel in her white mink stole on the 1962 Atlantic cruise where Arthur Miller apparently made a play for her; Phyllis in her kitchen, a calendar in Polish hanging over her shoulder; devoutly religious Millie and George at the Connecticut shore in 1937, wildly, carnally, in love. If they are here with us, surely, then, they must still be alive. My college lacrosse stick rests alone on a shelf; I pick it up and cradle it in my arms and it’s 1982. I am nineteen and my father is not yet sixty, and Harris is eight years old. My cousins, alive, dead, no longer in communication, are here with me. Susan’s aunts are here with her.

As long as we have the stuff — the photographs, the tapes, the bits of ancient pottery, the corks — time is anchored in place. Or so it seems.

A few weeks ago, we had the entire interior of the house painted. Susan loves color. When I first moved to her house in the country, every room was a different shade of pastel: peach, green, yellow, like a basket of Easter eggs. When we moved in here, she painted individual rooms herself: butternut squash for the kitchen, the guest room a wrought iron gray, the bathroom a weird taupe that never worked with the pea green 1970s tile. After a decade, it felt busy and distracting, a background for the things in our lives that gathered dust in every corner of the house, but mostly in the basement, where no one could see them but us.

I wanted every room to be painted the same color. I wanted the trim the same color, the wall alongside the stairs down to the basement the same color. I wanted my office to be the same, the kitchen to be the same, the den with its brick fireplace: the same. We argued about it. And then we hired painters, who moved everything we owned — the things we carried into our life in this house and dropped like an anchor — into enormous piles in the middle of every room. The walls were painted a bright white, as though the entire house was dipped in promise. After two weeks, it looked clean and fresh and uncluttered, like the beginning of new lives belonging to other people. The things of our pasts, obscured with drop cloths, were suddenly invisible; our stuff was gone, and all we had was ourselves, our home, our name. A blank slate.

After the painters left, we began to put things away. We stopped. It was overwhelming. A week went by. We couldn’t face the task. What to keep; what to weed out.

What are the memory triggers that bend our hearts? What are the things that break them?

I unpacked my office, since it is where I work every day. We hung our entry way mirror and the massive 1929 Italian poster that we bought for the wall above our basement stairs. We put away our pots and pans, and Susan attached a single magnetic knife strip to the wall next to our stove, to hold just five knives, not thirty-two. Everything else is still in boxes. We’re almost afraid to reopen them, to be dragged back into the past and unable to see the future.

I spent yesterday in the garden, weeding around the raised beds and the four roses that are suffering under the strain of the Virginia Creeper that threatens to strangle and siphon away their nutrients.

Let the Creeper climb the fence, a master gardener friend once told me. It’s beautiful.

But it’ll overtake everything, I said.

You just have to pay attention to it, she said, and not let it get out of control.

We refuse to use garden poison for fear of tainting our vegetables and our ground water. It might kill something we need, something we love. It’s a balance: what to keep, what to pull, what to release. The living versus the dead, the past versus the future. A constant battle against chaos.

What we have, Jane Kenyon once said, is the present. It’s all we ever had, really, except for memory.

May 2, 2017

the things we never say.

I can pinpoint when it happened, when I realized that writing about the table could be a bonafide job: it was April 1984, in Boston. I was sitting alone in my suite on South Campus at Boston University, and I picked up a copy of Gourmet that someone left on the living room table. I read it from cover to cover. One article was about a young woman who had studied cooking in Paris and was spending some time in northern France. A photograph showed her dressed smartly — skinny jeans, a striped shirt, a slouchy cloth bucket hat — and standing in a field with a cow. She was nuzzling the cow; the cow was nuzzling her back. I vaguely remember the caption: The cows are very friendly in this part of France. I was mesmerized. There were a few recipes and a picture of a table laden with food — nothing fancy — and short, footed glasses of wine, of the romantic, rustic variety that a French farmhand might hoist after a morning in the field.

A few days later, one of my cousins asked me what I was planning on doing after graduation. I had been thinking about going into academia, which didn’t thrill my parents. I considered law school, which didn’t thrill my English professors. But when my cousin asked me this pointed question, it took me two seconds to answer: I wanted, I said, to write about food and wine.

My cousin was very kind, but my response baffled her. At that time, no one in my family read Gourmet. Who could possibly imagine holding down such an outlandish job (if it could be considered a job at all)? After I said it, the subject was changed, and I never brought it up again, to anyone.

It took a few years for me to nudge my way into the food world. There was a job layoff from a now-defunct publishing house, and a short spate of unemployment. There was the morning that I sat on my living room floor in my walkup apartment on East 93rd Street, with the New York Times job pages opened up, and the ad for book buyer at Dean & Deluca. I called and went down to Soho for an interview, and got the job. I started the next day. I was surrounded by books — all of the Elizabeth David volumes in imported Penguin paperbacks; M.F.K. Fisher, in the lovely, French-flapped reissued editions published by Jack Shoemaker at North Point Press; Auberge of the Flowering Hearth; Richard Olney; John Thorne; Alice Waters; Felipe Rojas Lombardi; Laurie Colwin — but also food of the most astonishing breadth and variety. Somehow (and it embarrasses me to say this: it’s such a weird word) it was discovered that I was what they horrifyingly used to call a supertaster: I would stand in the back of the store with a handful of other colleagues, taste samples that had been delivered by purveyors and producers from Tuscany to Tulum, and identify obscure ingredients in the most minute proportions. At days’ end, we would sometimes go out — sometimes to The Cupping Room, sometimes to Jerry’s or Raoul’s or Food — and talk about what we ate all day while we ate more, and drank insane, ridiculous quantities of wine until we could barely stand. This was in the late 1980s; there was also a fair amount of cocaine, which enabled everyone to stay out until three in the morning, sleep for a few hours, come back to work, and slice cold-smoked County Mayo salmon so thin that you could read the newspaper through it.

I wasn’t much for the drugs — cocaine terrified me, and like Woody Allen in Annie Hall, the last time I smoked pot I tried to take my pants off over my head — but man, the wine. I loved it, and it loved me right back. We became inseparable. My customers would ask for advice: Bandol, Beaune, or Zin? Chianti, Barbaresco, or Bordeaux? I would answer them in great detail, down to the year: ’83 was my favorite, especially for tannic Rhones, like Gigondas. I had educated myself: I actually knew what the hell I was doing because it was my job. A little while after I left the store, I found myself regularly invited to wine tasting dinners, sometimes twice a week: six courses, each place setting surrounded by a small army of Riedel glasses: Chablis, Sauternes, Gruner, Chianti, Bordeaux (Mature), Burgundy, Cognac, Water. We were all professionals to some degree and we all managed to hold it together, even though by the time the Burgundy was poured, most of us were so smashed that we couldn’t tell the difference between the seared foie gras and the lollipop lamb chops if you blindfolded us.

In my home kitchen, there was more wine: the Salice Salentinos I loved to sip while cooking for my family and friends. The cool, round Cakebread rose I’d open when the temperature climbed above sixty. The Barolos I’d pour when it snowed and everyone I knew showed up for the game birds I liked to roast and serve perched atop polenta and wild trumpet mushroom ragout. At family functions, I was the one who knew about food and wine, who could talk about Emilia Romagna and Languedoc like they were in my backyard. Wine and food made me funny and confident and smart, and pulled me out of my thick, protective shell: in my family, I went from being a dour, quiet, chronically-depressed teenager navigating the waters of my parents’ failing marriage to the bawdy, tipsy grown-up cousin pontificating about the provenance of the Alsatian muenster and dribbling her overpriced kosher Bordeaux onto the pages of her Passover Haggadah. The rituals of my life began to merge with the requirements of my profession like a Venn Diagram, and at its gray, overlapping center was excess. After years of this — the tasting events, the wee sips before/with/after dinner, the professional vodka samplings after which it was assumed I’d drive myself home, an hour away — my so-called supertaster palate was shot to hell, gone, adios, sayonara, along with my feet; that much alcohol … that much pure, unadulterated sugar … had effectively killed my supposedly nuanced tastebuds and slapped an extra twenty pounds around the center of my five foot one, sturdily-built, formerly size six frame. I looked in the mirror, and my bubbe from the old country stared back.

And this is the thing about the food world that no one ever seems to talk about: being a food professional — a writer, a chef, a caterer, a wine distributor, whatever — totally legitimizes excess, be it on the plate or in the glass or both. Comus, God of Excess, representing chaos, a wreath of flowers on his head and a torch in his hand always in the process of being dropped, is the son of Bacchus, God of Wine; it’s a very slippery slope. If you have just the tiniest smidge of a predisposition towards addiction in whatever form it comes (Instagram, Facebook, anger, Twinkies, whiskey, yoga, Blahniks) and even if you don’t, you will be fighting the worst ogre of all, and that little demon inside you — the one who promises that what you’re doing is for work, or for ritual, or for both — is going to convince you that getting stuffed and/or hammered in the name of all that is culinary on a regular basis is really okay. Because, after all, it comes with the gig. And then, as thirty-five becomes forty, and forty becomes fifty, your body will begin to break down: your blood pressure will soar, your thyroid will die, your weight will climb, your neck will sag like a child in a hammock, and your face will start to resemble a sort of pouch. Your liver will fatten up like a goose in Toulouse, and all those Bandols, Beaunes, Bordeaux, and Barolos that you swirled and savored and drank with the most perfect very French-style rosy-pink lamb or Umbrian wild boar braise will take their toll. If you’re lucky, you’ll know when to stop, or at least when to cut way back because you’ll begin to feel like you’re hauling around a sack of potatoes strapped to your ass. If you’re not lucky, you’ll have a nice come to Jesus moment right before they put the stents in, and you’ll know that food and wine are just as delicious when had in moderation. Maybe moreso. Or, in the case of the latter, maybe not at all.

I grew up in the 1970s, and back then, the d word that everyone — food and wine writers, magazine editors, health gurus — now loves to throw around meant one thing: a stay at Betty Ford or Hazelden. Today, detox has been usurped by everyone from Gwyneth Paltrow to Bon Appetit to the Pinterest food boards: we live in a binary world accepting of extremes, of feasting and fasting, where detoxing no longer means a month inpatient, but a delicate bowl of steamed green broccoli, a dollop of artisanal goat yogurt, and a sprinkling of dukkah, or a bright purple smoothie topped off with hemp seeds soaked overnight to make them more digestible, or a ten day juice fast.

So laden with the assumption of excess is the world we live in that the fact of too much is just something we take for granted, like clean air and fresh drinking water and guns. But what would happen if the food and booze community — those of us who glamorize the massive portions and the artisanalia and the out-all-nights-eating-ramen, the vintage cocktails and the whiskey parties — not only preached the moderation we love to snarkily laugh at every January when detoxing grabs the headlines, but actually practiced it? What would happen if moderation was romanticized in place of decadence? Detox is a word and a practice that is now glorified; something is seriously wrong. All of this yearning and hungering and gorging and drinking signifies a certain longing for nurturing, a need for sustenance in a world that, with every passing day, grows more and more enraged, and we, more disconnected from each other.

It’s been thirty-two years since the day I picked up Gourmet Magazine, and twenty-eight since I went to work for Dean & Deluca, did a stint in cooking school, and began to attend regular meat-a-paloozas, deep-fried vegan patty festivals, craft beer bashes, wine tours that poured four massive glasses with every course (at lunch and dinner), and whiskyfests that left me with great human interest stories, but otherwise staggering. In 2013, I was diagnosed with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, an aortic aneurysm, hypercholesterolemia, and high blood pressure. Since then, I’ve changed the way I eat and drink; I’ve had to. And I feel better. But I still struggle to think about food and wine in smaller portions and moderate pours. Excess is what I’ve known for so many years, and, as I’ve written here, my off-switch sometimes gets stuck in the on position.

Every day is no longer a feast; it shouldn’t be. I still take pleasure in feeding the people I love, but the joy and sustenance I used to associate with decadence I now find elsewhere: in doing good work, in my garden, in my yoga classes, in art, in the company of friends and family, in the mundane, quiet life I’m lucky enough to live with Susan.

And that’s enough.