Elissa Altman's Blog, page 2

April 10, 2017

because I wanted it.

A few weeks ago, I attended a writer’s retreat in Bridgehampton led by my friend and teacher extraordinaire, Dani Shapiro, whose new (remarkable) book, Hourglass, is about to be released tomorrow. We were a small group of women writers at the beautiful Topping Rose House; the workshop was an immersive, intensive experience capped off each day by Nancy Alder’s great restorative yoga, which was held in a small barn on the property. The cool, calming, monochromatic accommodations were luxurious in their simplicity; they let the mind rest at the end of each day. The surroundings, Dani’s teaching, the yoga, the sea air in early spring — they all conspired to quiet my brain, making the place ideal for the generative writing experience it was.

After four months living in a state of high anxiety, the few days at the workshop affected me in the same way that Marie Kondo’s life organization book did; I could finally focus. I could see the promise of the serene on the horizon of my frenetic, hysterical life. As a rule, I believe that things would be better if I wrote more, owned less, ate less, drank less, weighed less, had fewer chins, and lived a hygge-ish life in reassuring, subtle shades of gray and white. I arrived at the workshop with the plan to use it as a creative reset after the last few very trying months when everything — my work, my home, but most of all, self-care — has gone by the wayside. The night after our first group dinner boded well: without the stimulation of the brash and loud, I fell asleep in my soaking tub while reading the new Joan Didion.

Jean-Georges Vongerichten is responsible for the food at The Topping Rose House, and it is stellar. The restaurant staff turns themselves inside out to make sure that every diner with every permutation of dietary restriction is accommodated, and so, on the first morning of my stay, when I ordered gluten free toast (from the menu) with my eggs and house-made spicy maple-chile sausage and my server asked if I had a gluten allergy — not a sensitivity, but an allergy, which I took to mean like the one my friend in LA has; she has to give herself a shot of adrenalin to keep from going into anaphylactic shock if she accidentally ingests a breadcrumb — I, with self-care in mind, said Yes. Because I’ve learned that gluten, in many cases — not all, but many — can make me unwell, and I didn’t want to run the risk of eating something that was going to make me ill to any degree. My truthful answer to the server’s question — that I have a sensitivity and a thyroid condition worsened by gluten, but not a potentially fatal allergy — would, I decided, possibly result in my situation being taken less seriously. So I answered the way I did even though a sensitivity is not the same as an allergy, and feeling drunk and drugged and euphemistically undone is just not the same as dropping dead.

My breakfast arrived along with everyone else’s; we were all gabbing and drinking our very dark coffee and eating our very crispy smashed potatoes sprinkled with flakey sea salt along with our local eggs. Everyone had ordered simply, and without any fuss or special requirements. I spread sweet butter on the slice of pale beige gluten free toast that came with my dish and it was fine. It wasn’t stretchy and pliable because it couldn’t be. Being gluten free, it was not the same as the other bread that had arrived for my friends — the bread I secretly lusted after in my heart — and that I couldn’t take even a teeny bite of because I had just announced to the entire universe that I am unlike everyone else. I am different. And this made me feel very badly, and covetous, and a little enraged. And when I get enraged, I tend to take my fury out on one person: Myself. And I engage in activities that might be considered the complete opposite of self-care.

That night at dinner, more baskets of warm bread arrived on the table. One of my friends ordered crispy calamari as an appetizer, and like a misbehaving child, so did I. Because I wanted the crunch, the crumble, the salt, the bite. I wanted the batter without the squid. I didn’t want to think about what I was eating, and instead, to just enjoy it like everyone else. I didn’t ask the server if it was dredged in corn meal (gluten free) or einkorn flour (not gluten free but tolerated by many gluten sensitive people) or gluten free flour (not likely) or locally-milled flour (likely) in order to gauge exactly how unwell I might be at the end of the night. I said fuck it, and just ate it, and I followed it up with a piece of warm bread, which I blithely dunked into the (flour-thickened) jus on my pastured roast chicken.

I had just succumbed to what my novelist friend Jane Green calls a case of the fuck-its.

Fuck you, gluten, I thought. I’ll show you.

My workshop-mates were lovely and said nothing. If it had been me on the other side of the table, I would have tried to keep my heart open in an accepting and compassionate manner. A few years ago, I would have thought What an asshole. But that’s the old, judgy me speaking.

For a few minutes after the calamari, I was sated, happy, drinking a massive glass of Barbaresco and feeling completely normal and carefree. I had thrown caution to the wind without fear or concern about anything: not the fried calamari, not the bread, not the jus on my chicken, not the goblets of wine I kept ordering even though I’d promised myself I’d only have two because my shut-off switch sometimes gets stuck in the ON position.

When dessert arrived, a wave of self-loathing swept over me like the ocean at high tide: when the chocolate cake I ordered was set down in front of me as everyone else ate their sorbet, my ears turned red with hot embarrassment. What I had done was inexplicable, and had I been in unkind company, I would have been (rightfully) reamed for my behavior, and obvious lack of credibility. I felt morally bankrupt, and like everyone I’ve always complained about who claims to be gluten free and then — like the pleasure-hating Alfred Molina character in Chocolat who is found passed out in the front window of Juliet Binoche’s shop, his face smeared with ganache — takes themselves out to lunch in a different town and secretly sucks down a bowl of hand-twisted garganelle.

Which is what I ate the next night.

Everyone else had the salmon and vegetables.

I just got it for the rustic meatballs, I explained. They were spectacular.

So was the pasta. Everyone had a bite. We all enjoyed it.

The next morning, I woke up in my hygge sea of soft grays and whites with a raging migraine so bad that I thought my eyes were bleeding. At breakfast, my new friends were going to have to listen to me guiltily drone on about my suspect behavior the night before, and the fact that because I’m working on some serious life issues at the moment, I had gone on a self-destructive bender and ordered the most glutinous thing on the menu and ate it with abandon.

I’m sure it was just the wine, I said to one of my new friends, as she handed over an Alleve before the start of that morning’s session.

Of course, she agreed.

A few days after I got home, I came down with a sinus infection so hideous that it required two antibiotics and a steroidal puffer, much time spent in bed, and four boxes of tissues. I’m not positive that one thing had to do with the other; I couldn’t help but think it. There are articles about this kind of thing, which I will not post here.

I had a lot of time to think about what I had done. What is it that compels us to act this way — to say one thing and do another; to take a firm and public stand that impacts others (because foisting one’s dietary needs on professional kitchens does impact others, as it does when your friends know you as a gluten-avoider and go to the trouble of filling their pantries with gluten free crackers should you happen to drop by) and then throw it in their face; to announce at the top of your lungs the dietary restriction that makes you feel good and healthy and is the very embodiment of the self-care that you deserve, and then to do the opposite. To say I can be just like everyone else. I can handle it. Just watch me.

What compels us to not act in our own best interests just because we want something we’re not supposed to have? (Fill in the blank here. I’ll help: the non-gluten free bread; the secret box of chocolate; the fourth glass of wine; the eighth tube of lipstick; the entire sleeve of Fig Newtons that my father used to binge on in the closet when he was furious with my mother, which was always). Because, in our world of instant gratification coupled with the fact of too much of everything, we want what we want when we want it.

But to quote Augusten Burroughs, Just because you want something doesn’t mean you have to have it.

At its core, this is the addict’s lament, the same thing that pushes the drinker off the wagon, the pill-popper to say why not, the gambler to take the bus to Reno: Sure, it says, I can be just like everyone else. Only, I can’t. And that makes me feel very badly. And when I feel very badly, I do everything in my power to make myself feel even worse, as though I’m somehow punishing myself for the fault of my own sheer humanity.

I want what I want when I want it is more than a credibility issue: it results in a metaphysical tangle that would make Marie Kondo’s head explode. Whether you’re talking about too much stuff that you wanted when you wanted it — the five striped shirts instead of two; the twelve pair of flats instead of three; the purses; the fifteen tubs of powder like the ones hidden away in my mother’s vanity — or the inclination to gorge yourself on what you wanted even though you’ve told the entire world you can’t eat it but you do and you end up feeling like a you’ve been hit by a paving truck, the result is the same: a muddled brain, a monkey mind, an overabundance of psychic stuff that no amount of hygge will help you cope with.

It took me nearly three weeks to get over my sinus infection; I spent much of it in quiet reflection and review of the chapter I’d workshopped in Bridgehampton. The original version felt heavy, laden with excess, stuffed with dross. Susan made a pot of chicken soup for me and clarified it over and over, pouring it through a fine mesh sieve until all that was left was a crystalline broth. I drank it out of a hand-thrown mug while wrapped in our vintage 1940s Hudson Bay blanket, gazing out the window at the world, anxious to start over.

[image error]

February 27, 2017

On Eggs, Sustenance, and the Maternal

I couldn’t peel it; my hands shook.

I ran them under cool water and dried them on my favorite blue striped linen towel hanging off the oven door handle — the one that I never use, that I’m afraid to stain lest it cease being the new, fresh, perfect towel that it is. Still, my hands trembled, and when I tried to peel the morning’s freshly boiled egg, I failed. I brushed the shell away with my thumbs to coax it off like my grandmother used to do when she made eggs for me in the chipped black and white enamel saucepan of my childhood. Instead, I gouged it violently, my thumb piercing straight through membrane, glair, crumbling orange yolk with its halo of overcooked green, until all that was left of the egg was the suggestion of sustenance.

My throat tightened. I fought back tears, and laughed at the utter ridiculousness of it: to cry over a mangled egg is inane and emotionally frivolous. Boiling an egg on this particular morning during this particular winter was all I could possibly manage, and I couldn’t even manage that.

We call one another good eggs, tough or rotten eggs….We walk on eggs to spare fragile egos….We find the bestowal of an egg to be expressive of wildly divergent emotions: handed over graciously it betokens favor; delivered at high velocity it plainly indicates disgust, said Robert Farrar Capon. I add to this the egg’s subtext of Life, cap L, and hope: in The English Patient, when David Caravaggio, erstwhile spy and thumbless thief, produces a single, purloined fresh egg for Hana, it means that the war is nearly over. When he drops it and it splatters at his feet, we know that the war will continue, however briefly, and more will die.

I grew up having an egg every morning of my life. My father and I sat side-by-side at our Danish modern kitchen counter in Forest Hills, our backs to the Chambers stove where my mother silently soft-boiled two of them for three minutes, cracked them over slices of cold diet white bread stuffed like cotton balls into two brown melamine egg cups, and set them down in front of us. Years later, in the egg white omelety 1980s, I began to curtail my egg intake because of the genetically high cholesterol I was gifted from my mother. In the 90s, I discovered oeufs en meurette at the defunct La Goulue in Manhattan, and would have them once a year when I took my mother to her favorite restaurant for Mother’s Day. In the early 2000s, I married Susan, who taught me how to make a meal out of a perfectly poached egg on garlic-rubbed sourdough toast drizzled with olive oil; we ate this at least once or twice a month. In the mid-early-2000s, when I began to write full time from home and was blessed with a chicken-keeping neighbor, I started making a single boiled egg every morning: I would sprinkle it with sea salt, roll it around in a shallow stoneware dish of dukkah, and eat it standing up in the kitchen, the dog at my feet. And then, like clockwork, my mother would call.

I can’t talk, I’d say. I’m having breakfast. I’ll call you back.

What are you having? she’d ask.

An egg, I’d say, my mouth full.

I’ll stay on the phone with you while you eat, she’d say. I’ll do the talking.

And she did: sometimes happy, sometimes angry, often raging against one person or another who had somehow done her wrong. There were laundry people who used the wrong detergent, cab drivers who took her the wrong way to her destination, makeup that she’d ordered that didn’t arrive when she needed it, an accompanist who didn’t return her call, the Jewish deli that forgot to remove the peas from her matzo ball soup. There were old friends of sixty years with whom she was engaged in constant battles, bus drivers who drove too slowly, bus drivers who drove too quickly, the cable company who was trying to bilk her, her long-deceased ex-husband — my father — who she was convinced was crazy, her second husband who didn’t make provisions for her before he died of a cerebral hemorrhage, and Perry Mason, who she was completely in love with even though 1) he didn’t actually exist in real life; 2) Raymond Burr was dead; and 3) when he wasn’t dead, he was gay.

It wouldn’t matter to me, she’d add, and continue on.

I have to go, I’d say, wiping the dukkah crumbs from my mouth.

After her fall in December — after the surgery and the rehab and the return to her home with a caregiver — her morning calls came earlier. A pre-dawn text from the caregiver would come in first: She’s calling you in five, she’d write. Just FYI.

By January, cartons of eggs — my neighbor’s chicken eggs, a plastic tray of quail eggs, six duck eggs that I’d bought over the holidays as a treat — began to pile up in the refrigerator, shoved into the back alongside half-empty jars of Hellman’s mayonnaise and squashed tubes of anchovy paste; I lost track of them, and couldn’t remember which ones were old and which were fresh. I forgot to eat breakfast, and sometimes lunch. I’d look up from my computer at three o’clock, the sky outside my office beginning to change, and realize: I hadn’t eaten anything all day. My skinny jeans began to hang off me.

You look terrific, my mother would say, when I’d come to visit every week. You have cheekbones again.

How are you sustaining yourself, a friend asked me. What’s the easiest way for you?

Eggs, I told her. But I have no appetite.

Don’t you understand, she said. Eggs are life. They are perfect. Boil one for yourself. Every morning. Even if you don’t eat anything else until dinner, you’ll be okay.

The next day, after Susan left for work and the dog had been walked, I took out the carton containing the ones from my neighbor; they were large, small, narrow (one of her girls lays eggs that are nearly flat), round. They were blue, green, and white. There were brown speckles on some, and bits of feather stuck to others.

I placed a small green one in my favorite ancient Le Creuset butter warmer. I filled it with water, put it on the stove, and when it boiled I covered it, removed it from the heat, and set the timer for twelve minutes. When the bell went off, I drained the pot, ran the egg under cool water until I could handle it, stood over the sink, and tried to gently peel it. The phone rang four times and stopped.

I peeled.

The phone rang again and stopped.

I peeled.

The phone rang again, and I plunged my thumb through the shell; it came out the other side. I cried at the absurdity of it: I was a food writer who couldn’t even feed myself an egg, or provide myself with the most basic form of life-giving sustenance. The egg is arguably the world’s most perfect food and I had destroyed mine. I dropped its remains into the butter warmer, and put the pan in the sink. I looked out the window at my backyard, partially covered with snow.

The cold New England winter sun streamed into the kitchen; it was a quiet time of day.

The phone rang again; I let it go.

I picked up what was left of the egg, and did the best I could with it; it was misshapen in places, broken, flecked with shards of shell. I dropped it back into the tiny pan, sprinkled it with sea salt and dukkah and ate every last drop with my fingers, savoring its promise of sustenance, its imperfection, its symbol of the maternal.

January 4, 2017

Look for the Helpers

Am I safe here? the woman whispered.

She was tall and blonde and classically northern midwestern looking, and had come from just over the Wisconsin border to attend a memoir class I was teaching at The Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis.

Am I safe?

Her voice quavered; strangers — all of us — shook our heads.

Yes.

It was early in November, the day after an epic, divisive moment in time. We were in a beautiful classroom at a remarkable literary center in a lovely city filled with people of every color, religion, and political persuasion. Minneapolis is a place I had long wanted to visit, and to teach at The Loft was a long-held dream of mine, ever since I’d heard Natalie Goldberg talk about it more than twenty-five years ago. And on this morning, sustained by strong coffee and ensconced in a building that at its core is devoted to writers and books and the written word, a small handful of us who had never before set eyes on each other assured this woman that yes, she was safe.

If not here, I said, then where.

I recognized the telltale signs of anxiety that I know so well: for me, it comes from the unshakable certainty that one is unsafe. The nervous shifting, the eyes darting, the foot tapping, the frantic water drinking, the shallow breathing, the coat thrown on and off and on and off. Anything to keep moving, to keep running. For the anxious, stillness and quiet can be as unhinging as a night terror.

Add to this the fact that memoir — the teaching of it, the talking about it, the writing it: the permission, the memories, the emotional fortitude that it takes to plunge deep — is a gnarly bit of business; at best, it’s fraught. At worst, it can make the strongest of us feel ungrounded and unmoored and like our limbs are made of jello. Those of us who write it — who come back to the form over and over again — do so because we can’t not. We do it to uncoil our stories, to know our truths, to understand who we are through the specter of who we, and the people around us, once were.

Am I safe here.

Yes, we said. In my classroom, in my space, you are safe. But step outside into the wide world, and who knows about any of us, at any time.

(I didn’t mention that.)

By the time I arrived in Iowa for my next book event, I was depleted; I felt like an IV bag that had its contents forcibly squeezed out of it. I was shaky and nervous and unsure and exhausted. My writer/chef/restaurateur/publisher/county supervisor/devoted Unitarian friend Kurt picked me up in Cedar Rapids and dropped me off at my hotel, where I tried to nap; I met my writer/journalist/born-and-raised evangelical friend Lyz for lunch. No three people could come from more opposing histories, with more divergent views on everything from politics to religion; in fact, we have more in common than we know. We talked about safety and writing, about division and how to move forward into the unknown in a way that is sustaining and nurturing for all of us, not just some of us. We talked about being ferocious and fierce and kind and devoted to community and family — that those qualities aren’t mutually exclusive — and sitting opposite Lyz, my hands shook as I ate my carrot ginger soup at a lovely little cafe in Iowa City; I couldn’t manage anything more substantial than that.

Look for the helpers, Kurt said to me that night, quoting the late Fred Rogers; it was Kurt’s wife’s birthday and he had cold-smoked a pork shoulder for ten hours, and braised it in lamb stock into which he had sliced a few local Iowa apples. It was an earthy dinner, rooted in place and ground. Another couple — they were much older; we’ve seen it all, they said — came over to join us for Kim’s celebration, and to drink to friendship and safety and sustenance.

Look for the helpers, Kurt kept saying. Remember that.

I returned home from my book tour in early December. A few days later, just as I was beginning to unpack and start work on my next book, Motherland, my mother fell in her apartment. Surgeries. Rehab. A treacherous, bottom line-driven healthcare system designed to fail the people who need it most: its seniors, its children, its poor. What Dickens called, in A Christmas Carol, the surplus population.

What are we going to do, I cried to Susan after sixteen hours in the emergency room, and thirty without sleep. My mother never planned for a catastrophic event; my mother has always assumed it would happen to someone else.

Look for the helpers.

I did, and they were there: phonecalls, emails, advice from people I’ve known from my childhood in sleepaway camp, from my social worker yoga friends, from my neighbors, from a lawyer-turned-food-writer friend with a penchant for spreadsheets and information gathering. Facebook messages flew back and forth, and good wishes and prayers came from places I would have never thought would send them.

Weeks later, Susan and I tried to assemble a Christmas of sorts, with cousins around our table, wine, and simple food; it was a quiet time. The morning after Christmas, we were back in the emergency room, this time with Susan and a kidney stone. Sitting next to her, holding her hand, this person I’ve spent nearly twenty years with, and watching her in such excruciating, withering pain, it felt like it was just us and the world and a universe that was hitting us, repeatedly, with what one of my friends calls the shit stick. Humans are a beautiful, broken, feeble, complicated lot; our minds overtake our bodies. Our bodies overtake our minds. In the last year, I have had three healthy friends younger than I suffer heart attacks; they all survived, one barely. One of my dearest friends had brain surgery after collapsing in an exercise class. Another friend had a hiking accident that easily could have killed her. My cousin was diagnosed with cancer. A friend’s brother was nearly lost in a car accident. We put Addie, our sweet old yellow Lab to sleep in July, the day before Susan’s birthday. Our other dog was diagnosed with cancer; our cat stopped eating. We live in what Anne Lamott once referred to as the waiting room of the emergency ward.

Talking about food — the next great trend; the next cool technique — feels frivolous. How can I cook? How can I nourish myself and the people I love and my community?

How can I eat?

The world spins forward. Together, we lurch into the future, into that place where, now more than ever, we need the nurturing and the sustenance.

At 3:08 am each morning since my mother’s accident, I am catapulted awake; I hear Susan breathing softly next to me and the dog snoring on the floor. This is my home, the place that grounds me, that tethers me to the earth. This is my family.

The alarm will ring in two hours.

My student’s words careen around my Monkey Mind like a broken record.

Am I safe here?

I lay in the silence; I listen to the quiet.

I try to assure myself as I assured her.

You are safe here.

I doze until the sun comes up, and I begin again.

November 2, 2016

And the snow turned into rain

Last week, I drove to Boston for readings and signings at the great Wellesley Books and Brookline Booksmith, the latter of which was my local independent bookseller in the 1980s when I was a student at Boston University. Returning to Boston always feels like coming home, but it’s also bittersweet; it was the first place I lived alone, the first place I learned how to cook for myself (The simple: eggs, bowls of rice, steak, chicken soup. The tortured: pounded veal cutlets rolled around a filling of crispy pancetta and Fontina Val D’Aosta, and braised in dry Marsala fortified with a pound of butter. Vile.), the first place I discovered what being secretly, completely, hideously in love felt like.

This particular person cooked and so I did, too. That’s the way these things go.

At the time, it seemed incredible to me that someone my age could feed, nurture, and sustain herself and the people she cared about. Cooking, I thought, was an act reserved for older people — parents and grandparents — taking care of themselves and their families. People my age were why pizzerias and Cup-a-Noodle and sub shops were invented. I was sure of this.

Like most BU students, I crept my way further west down Commonwealth Avenue with each passing year, until I found myself no longer living in Boston, but in Allston, on the Brookline border. In the mid-1980s, it was a rough place to live; rumor had it that there were more cockroaches per square inch in Allston than people, and I once came home from my summer job as a Beacon Hill psychiatric practice assistant to my first apartment — an L-shaped studio directly upstairs from the area’s first Thai restaurant; every day, delicious clouds of lemongrass and curry wrapped themselves around me like a blanket — where I was greeted by a four inch-long water bug as exuberant as a puppy. My downstairs neighbor was a jet black-haired bass guitarist in a punk band that played every week at The Rathskeller in Kenmore Square ; he liked to position his amplifier on its back and crank the volume so loud that when he practiced, my shirts swayed back and forth in time where they hung in the closet. When I politely complained, he appeared at my door with a baseball bat, a row of safety pins piercing the entire width of his lower lip.

The 1980s.

BU Boathouse, Charles River, College of Liberal Arts, 1982

Every weekend during the school year and the summer, my ritual went something like this: wake, coffee, eat breakfast (eggs or oatmeal if I was feeling virtuous; cold, leftover pizza from T. Anthony if I was hungover, which I often was), walk into Brookline to the Booksmith, past the beautiful, sprawling Victorian homes with their deep, tidy porches and ancient, massive elms. I’d dream — this is what you do when you’re in college — about the future, about the object of my affection, about safety and security and love, about growing up and growing old in a rambling, drafty old house in Brookline with a massive kitchen and creaking floor boards. I’d imagine myself living there, and by the time I reached the bookstore, I’d be lost in a reverie undone only with the purchase of a stack of remaindered paperbacks, and, at the neighboring health food restaurant, an iceberg lettuce salad tossed with a handful of cold canned garbanzo beans, and a small, damp sandwich made from something called Mock Chick’n Surprise.

But living there was not to be; by the time I graduated in 1985, I couldn’t wait to leave. Most of my closest friends — there were seven of us — had graduated a year earlier and were gone. I had been in love for the first time in my life — wildly, stupidly, mind-bogglingly so; unrequited and embarrassing, it surprised both me and the object of my forbidden passion: a deeply devout, very straight, Episcopalian woman from western New York State — and everywhere I turned were reminders of us. The day after graduation, I packed my father’s rented U-Haul in less than an hour; when I arrived at my mother’s apartment in Manhattan that evening, I realized what I’d left behind in my haste to get on with my life as an adult: my rusted-out Ross Eurosport bicycle, a box of photographs of my college friends, a Vietnam-era Army jacket I’d found in a used clothing store at the start of my freshman year, the name patch — Corporal Tedesco — beginning to fray with time. The only thing I took: my guitar, my clothes, my books, and the white and blue-flowered Correlle-wear service for twelve that my father bought for me when I moved into that first apartment: if I was actually going to cook, he said, I was damn well going to cook for someone other than myself.

I didn’t return to Boston for a long time; it was too hard. When I finally did, I imagined that I saw her everywhere, in quick glimpses out of the corner of my eye, down alleys and side streets where we used to walk after class, on leafy St. Paul Street in Brookline, at the vegetarian restaurant on Harvard Avenue, outside the Victorian house with the rambling, open kitchen where I was certain we’d live someday. The thought of her left me undone, and when I ran into her ten years later at the funeral of a mutual friend, she talked to me as though nothing had happened; the weight of our story had been carried only by me.

Did you ever learn how to cook, she asked.

I went to cooking school, I said.

She hugged me and smiled, and floated away like a ghost.

Allston and Brookline at sunset from 700 Commonwealth Avenue, 18th floor, C tower. 1982

When I arrived in Boston last week, the day after my Wellesley reading, I did what I always do when I first get there: I parked the car a little bit west of the building that was my freshman dorm — Warren Towers — and looked up at what had been my 18th floor window from 1981-1982. For one solid year, not yet out of my teens, I stood there and watched the sun set every night; I looked west into Brookline and imagined what my life would be like after graduation, where I would live, what I would become, who I would cook for, who I would love, and who would love me back.

Last week I stood on Commonwealth Avenue before my reading, gazed back at that eighteen year old girl and told her: she would find joy in the act of nurturing and sustaining others, and she would marry the love of her life, who actually loved her back. And that things would be good.

I wished her well, and drove to my reading.

October 18, 2016

All the meatballs in the world.

It wasn’t planned.

There wasn’t a secret memo saying We’re all going to make meatballs, FYI.

Last Friday, Susan and I managed to get the last two seats on a flight out of Raleigh Durham; I had flown down to do an event with the amazing Marcie Cohen Ferris as part of her Food For All project at UNC, and was on the fence about leaving because I had a few book signings planned for the next few days at the [amazing] Quail Ridge Books, The Regulator and Flyleaf books, but Hurricane Matthew bore down on the south and there was no guarantee that North Carolina would be safe (it wasn’t; the eastern part of the state was hit terribly hard, and there have been casualties) or that we’d be able to get home if the storm turned north. At some point in Raleigh Durham — land of voracious readers, phenomenal food, and lovely people — I decided to lift my knapsack up with my right hand and blithely fling it over my shoulder (this is the knapsack that ends up weighing 40 pounds because of my laptop, my iPad, the three books I carry with me everywhere and never read, my two Moleskines, and my various plugs and jacks). Mid-fling, I knew I was in trouble: I felt a sharp stabbing pain in what I know to be my coracoid process (my ex was a doctor), dropped my bag, and whined the rest of the way home. My amazing massage therapist had an opening the next day and I nearly passed out on her table. After it was over, all I could think about was Sunday dinner which, because I cannot use my right arm, would have to be made by Susan who — I never talk about this but I should — is an extraordinary cook. Not only is she great at everything she makes, but because she’s a book designer, everything that needs to be uniform is uniform. Like little soldiers.

It was debate night, and we wanted something comforting; we (suitably) opened up Julia Turshen‘s new cookbook, Small Victories, to the meatball recipe. We went out shopping, came home, and Susan deposited me on the couch with my iPad and my iPhone, both of which were showing low levels of battery juice, so I plugged one in while I mindlessly scanned the other. What the hell I was scanning for I will never know, but I know what I found: rage, enmity, divisiveness, fury, anger, panic, virtual pugnaciousness, tantrums, nonsense, paranoia.

And meatballs.

Many meatballs.

I texted a writer friend who lives nearby. She said she was making comfort food for dinner. What was she making?

Meatballs. (Lamb.)

Another friend in Seattle, hunkering down for their storm of the century, was also cooking. Meatballs.

Everywhere on Facebook and Instagram and Pinterest, scores of people who don’t even know each other were also apparently making meatballs. Some were healthier takes on tradition (pine nuts, masses of kale, ground turkey; grass fed beef, masses of kale, currants), some were fried, some were baked, and some (all pork, for the hardcore) were very traditional, and simmering in Sunday gravy. Some were vegetarian, some were vegan and made from lentils. But on this, the first officially cool night of the season, with the future of the country unspooling before our very eyes in ways that have left both sides of the aisle gasping for air, everyone, regardless of political persuasion, wanted meatballs.

It reminded me of this past summer, when literally every person I know was going to the water on vacation. Lake, ocean, river, pond — images of docks and lighthouses and beaches and sand clogged up Facebook and Instagram and Pinterest feeds like mud. Everyone, it seemed, was fleeing for safety to what is universally known as a source of healing and comfort, whether they realized it or not. As humans, we know when are souls are hurt; we know what we want, and how to nurture and care for ourselves.

Water; meatballs.

Still, we’re generally not big meatball eaters in this house. The few times that my beloved Gaga made them, each one weighed in the neighborhood of half a pound, making them more like polpettone than polpettini. She also was not of the mind to soak bread in milk and stuff it into meat — and not because she was kosher, which she wasn’t — but because she thought it was somehow wasteful; I loved everything else she ever made for me, but her meatballs were solid meat and the consistency of a Lower East Side handball: dense, rubbery, inconsistently bouncy. Also, I grew up in a Queens neighborhood blessed with several very good Italian restaurants (among them Lidia Bastianich‘s first restaurant, Buonavia), so there was really no need to make our own meatballs: if we wanted them, we knew where to get them.

When I make them, they’re invariably lumpish and hard, but the other night all I wanted to do was soothe my heart with a small bowl of them set atop a tangle of [gluten free] pasta blanketed under a rich, thick, garlicky tomato sauce. So that’s what Susan made: Julia Turshen‘s Small Victories turkey and ricotta meatballs. They were the very best I’ve ever had, of any kind, anywhere. By the time the night was over, I, like so many others, was worried, angry, bewildered, and sad that our politics has devolved into a sideshow straight out of Duck Soup.

I did the only thing I could do: I grabbed my bowl and headed for the kitchen, where the pot, still warm, was sitting on the stove, and had a few more.

Julia Turshen‘s Turkey + Ricotta Meatballs

from Small Victories

Possibly the best meatballs I’ve ever tasted. Julia Turshen calls for ground turkey, preferably dark meat; at first, I was dubious because every turkey meatball I’ve ever had could double as a squash ball. These were remarkably tender, flavorful, and so tasty that I’m still dreaming about them. One small change: the original recipe calls for Parmesan cheese. We used Parmigiana-Reggiano, freshly grated.

Serves 8 or 4 with leftovers (makes about 30 meatballs)

Two 28-0z cans whole peeled tomatoes

7 Tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

7 garlic cloves; 4 thinly sliced, 3 minced

Kosher salt

1 cup fresh basil leaves, finely chopped

1 cup Italian parsley leaves, finely chopped

1-1/2 cups whole milk ricotta cheese

1/2 cup finely grated Parmigiana Reggiano

2 pounds dark meat ground turkey

Pour the contents of the tomato cans into a large bowl (reserve the cans) and crust the tomatoes with your hands. Rinse one of the cans with 1/4 cup of water, pour it into the second can and swish it around to get all the excess tomato out of the cans, and then pour the water into the tomato bowl.

In a large saucepan over medium-high heat, warm 3 tablespoons of the olive oil, add the sliced garlic, and cook, stirring, until it begins to sizzle, about 1 minute. Add the tomatoes and a large pinch of salt and bring to a boil. Lower the heat and let the sauce simmer, stirring every so often, until it is slightly reduced, about 30 minutes.

Meanwhile, preheat your oven to 425 degrees F. Line a baking sheet with aluminum foil. Drizzle 2 tablespoons olive oil on the baking sheet and use your hands to rub it over the entire surface of the sheet. Set aside.

In a large bowl, combine the minced garlic, basil, parsley, ricotta, Parmigiana, turkey, and 1 tablespoon salt. Blend everything together gently but authoritatively** until well mixed. Then, use your hands to form the mixture into golfball-sized meatballs; the mixture will be sticky, so wet your hands with a bit of water to help prevent the meat from sticking to them. Transfer the meatballs to the prepared baking sheet as you form them. Drizzle the meatballs with the remaining 2 tablespoons olive oil and roast until they’re browned and firm to the touch, about 25 minutes.

Use tongs to transfer the meatballs to the simmering sauce (discard whatever fat and juice is left on the baking sheet). Cook the meatballs for 10 minutes in the sauce (they can be left in the gently simmering sauce for up to 1 hour) and serve.

**Best process instructions EVER, said the former cookbook editor.

October 4, 2016

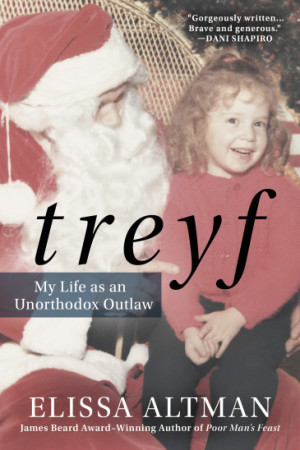

On writing Treyf

I’m only half-kidding when I tell people that producing a book — writing it, revising it, working with your editor, revising it again, getting reads from people you trust to look at your raw(ish) work, reviewing the copyedits, reviewing the typeset pages, releasing it once and for all to the publisher who sends it into production where it cooks over a period of several months during which you hear nothing and are driven mad by the silence until a box arrives and you rip it open and burst into tears and there is your book — is like doing Lamaze while running a marathon for (in my case) almost three years. Like birthing a baby, it is a labor of love. And although Samuel Johnson famously said “Nobody but a blockhead ever wrote for anything but money,” he was wrong: writers write because we are constitutionally incapable of doing anything but.

There are those of us who barrel from one book to another, without catching our breath. Some of us stop for a while, mid-stream, and come back to our work at a later date. Either way, it’s never easy: Masters of the form quake before the page, Dani Shapiro wrote in her seminal Still Writing, which, while I would not qualify myself as master of the form, made me feel marginally less insane on the days I spent staring at the computer screen, hyperventilating, trying to unravel the myth of an assimilated American Jewish family across three generations living in midcentury and deeply hungry — hungry for acceptance, hungry for illusory safety and security, hungry for love — until I got to the kernel of who they were in reality, who they were in myth, and who I am as a result.

Some years ago, I was ordered to stop writing, to put my pen down, to step away from the computer, to abandon my work.

It was a little crazy, and like watching a metaphysical spaghetti western being filmed on a backlot.

I can’t, I said.

Drop it, she said. Move away from the desk.

I can’t, I said. I held my hands up.

She drew first.

Her bullet caught me square in the chest, tore open my heart, and for a time, writing this particular story about being an alien felt, in itself, alien; early on, the words on my computer screen might have been cyrillic for all the sense they made to me. I had to heal my heart before I could come back to the work and to the act of unkinking the cord and clearing the line of static. I think that anyone who writes, whether they are overtly told not to or they just imagine angry gods hurling thunderbolts at them, faces this, at some point.

Ultimately, it is impossible for a writer to not do this thing that breathes air into her lungs, that she cannot escape. As I recently told Signature Reads, it was Junot Diaz who said that he writes because he can’t escape it, because it offers him a way to address and counter what it means to be human; this is why any writer writes.

This is why I write.

And this is why, at this particular point in my life — having published my first memoir three years ago — it was finally time to write about transgression, self-acceptance, and community, but also the issues of shame, overcoming hardship and pain, and, of course, love. Treyf is a story in which being an outsider longing for acceptance is a primary theme that plays itself out everywhere from religious practice to the dinner table to the bedroom. In writing it — in revisiting those times in which I overtly sought to always be a member of the winning team — I learned that it was the table and the act of nurturing that was the tie that bound us all together across the years, like a tether connecting divers in the muck, leading us to the light, bringing us home.

July 11, 2016

Marcella’s Ingredienti

A few years after Susan and I moved to our home in Connecticut, about two hours from New York City where I grew up, we decided to plant a small vegetable garden in our backyard. The patch we chose — we had few options back then — was sloping and irascible: while it got limited but strong sun every day, it also backed up to a thicket in which an entire family of woodchucks had taken up residence. It was like The Vince Lombardi Rest Stop for the neighborhood deer. Before we built it, our neighbor came marching over from her house with a handful of her family’s beans.

My great-grandfather brought them over from Italy in his coat pocket, and we just keep growing them every year she said. We all plant them.

I thanked her, and we gave them their own 4 x 4 box; the plants grew enormous and bushy, and yielded masses of flat pods five inches long and gorgeously mottled in pinks and creams, and sometimes a tawdry darker purple and green. When we harvested them, we cooked them together with minced garlic in a little olive oil, sometimes adding fresh sage. And every year, we let some of the pods dry in place so that we could store the beans for the winter. We’ve been doing this now for almost ten years, and for many of those years, we had no idea what kind of beans they were.

Pack some up and send them to me Marcella Hazan wrote, after seeing them on my Facebook page. I’ll identify them for you.

When Marcella Hazan instructs you to do something, you do it. So I did.

She wrote back to say that we had gotten it all wrong: these were shelling beans, the kind they grow in northern Italy, possibly Fagioli di Lamon, or maybe a sort of immature Borlotti. She giggled a bit at my ignorance — Susan and I had been eating the pods all along because they were so lovely, and sometimes they were as tough as balsa wood, as beauty often is — and then wished me well. From that point forward, we’ve shelled our beans, storing them through the winter for long-cooking with a little chunk of ham, but holding back a few cups to make at the end of every summer.

I tell this story not for the sake of ego; I tell it because of the complicated, aggressive times in which we live, and the fact that, very often, the food we eat and the way we prepare it reflects these times. When something, anything, is alluring to the eye — in this case, my beautiful, burled pods, grown from beans carried to America in the pockets of a homesick Italian man from another century — our inclination is to devour it quickly and in haste, all slapdash and high heat, without taking the time to understand and appreciate it’s true nature. An elemental rule, applicable to all facets of life: when presented with beauty, never take it at face value. Don’t gobble it up. Look for its truth. Speak its language. Seek its purity. Take your time with it. In the kitchen, be reductive: understand your ingredients. Know what they are, and what they want. The better the ingredient, the less it needs done to it. This is what Marcella Hazan has always taught us, and in a world where noisy, brash cooking devoid of connection to ingredient and designed to impress rather than sustain — all hat and no cow as they say in Texas — still seems to be the norm, they are lessons worth listening to.

And these are among the lessons imparted in Marcella’s glorious new book, Ingredienti: Marcella’s Guide to the Market, published three years after she passed, and completed with the help of her beloved husband and collaborator Victor Hazan. Compact, concise, and based on a lifetime of daily market visits, Ingredienti is Marcella Hazan at her most typically uncomplicated, unfussy, and unequivocal. Organized by ingredient from A to Z within sections that include produce, the essential pantry, and salumi, this is the sort of compendium that possesses the staying power of bedrock; small enough to be carried like a bible, in a purse or a pocket, Ingredienti marries Marcella’s inimitable voice to the practice of her life, wrapped around advice for choosing fresh vegetables, pasta, olive oil, Parmigiana Reggiano, prosciutto, and even the most deliciously mundane of ingredients, bread crumbs. Readers who otherwise demand formal recipes will actually have to read and absorb the book’s lovely narrative for the instructive, authoritative wisdom that it is laden with, but this is precisely what the best Italian cooking is all about: it’s a conversation between cook and ingredient. It is pure food made from the very best (but not always most expensive) of the marketplace, chosen wisely and used intelligently and intuitively.

Ingredienti comes at no better time for the American kitchen and culinary soul; as many continue to be utterly disconnected from the practice of cooking at its very root — at the market, where it begins — and instead prefer the supposed ease of trendy meal kits and on-line grocery stores that literally sever the vital connection between the consumer and the consumed, the process of sustaining ourselves has become further mechanized, disengaged, and detached. With the country descending into what feels like chaos, we need Marcella’s grounding, teaching, and guidance now more than ever.

At least I know I do.

June 23, 2016

Forgetting How to Cook

It’s the past that tells us who we are. Without it, we lose our identity. – Stephen Hawking

It was an early spring night when I incinerated the chicken.

Weeks earlier, I grilled a steak — a nice, grass-fed porterhouse the price of a Fiat — so well-done that you could snap it in half like a charcoal briquette. I’ve poached dozens of eggs to the point of bouncing; carbonized my morning toast; steeped my green tea until it was so bitter that it made me cry. At Easter, I roasted a local, acorn-fed ham until it collapsed into cords of floss. On Passover, I took pains to make a rich, robust chicken soup and then served it lukewarm with cold matzo balls, brisket that fell apart because I’d sliced it with the grain, and half-done sweet potatoes coated with a balsamic drizzle so cold it made my teeth hurt. Our guests were very kind, even though I somehow decided that it would be a nice idea to not open the incredibly lovely, short-run, signed-by-the-winemaker magnum of Pinot Noir they brought for the occasion. With dessert — Susan, thank God, baked an almond cake — I served them watery Mokas in tiny Duralex glasses, which made them look like thimblefuls of rainswept mud instead of espresso.

Does Emily Post have a chapter for this? Susan whispered to me when we were clearing the table for the second course.

For months, everything I’ve touched in the kitchen has turned to shit. My domain — the place where (next to my desk) I’m most tightly tethered, and where I best know my own identity — has felt as alien to me as Mars. The feeling comes as a familiar, discomfiting clench in my chest; a distinct but subtle panic not unlike the attacks that addled me from the time I was a child and sometimes, when I’m not taking care of myself, still do. There’s been a disconnect that I can’t put my finger on; it’s like I’ve unplugged the phone but I keep trying to make a call. On more than one occasion, I mixed up the dogs’ food — they eat two different kinds — and scooped a dollop of cat food into my terrier’s bowl. For months, I couldn’t feed Susan, my friends, my extended family, my animals.

Myself.

As I write this, I am a little less than four months away from the publication of my next book, a story of growing up in ’60s and ’70s Queens New York, always on the outside looking in, living life as a chronic misfit searching for grounding, security, family, and a certain way to nurture and sustain myself. Anyone who grew up in Queens back then knows full well: it was a crazy time, sandwiched one end of the decade by the Kitty Genovese murder and on the other by Son of Sam, the ’77 Yankees, Studio 54, Earthquake in Sensurround, key parties, bad hair, and The Partridge Family. It was a time of change — unfathomably rapid change — that left many of us so-called good girls in the position of having to choose between the people we were raised to be by our 1950s forebears, and the people we were destined to become. And as I wrote Treyf, I realized that this choice-making — often rule-breaking — was not just a function of the 1970s, when nothing was off-limits; piloting the waters of the (culturally, Talmudically, culinarily, emotionally, sexually) proscribed is what humans do, putting one foot in front of the other and schlepping forward into the future, into the unknown, into a world that is constantly shifting around us. Treyf is the story of this navigation, of stepping into the future with a need to cling to the past. It’s about the leaps of faith that we all have to take as we negotiate the universe; it’s about becoming inveterate rule-breakers — all of us, even our parents and grandparents — in the face of tradition even as we long for the security and supposed safety of that tradition. In order to evolve and become our true selves, we can’t do anything else, no matter who we are or what we’ve been raised to be.

And where there is rule-breaking, there is inevitably conflict; this is the way of the world. What was the feeling in the pit of my twelve-year-old grandpa’s stomach when he ran away from his small Ukrainian town in 1905, leaving his mother and siblings behind with the stepfather he hated? Would he stay or would he go, and escape the fate that they met when the Nazis arrived, forty years later? How did my Orthodox-raised father feel when he subversively made me Spam and eggs for breakfast one Saturday morning? At a time when I was raised to marry a doctor or a lawyer, did I dream of marrying a poet or a painter, a man or a woman? There were other choices to make in the writing of the book: would I tell my story transparently, or would I hide my story? Would I carry forward a constellation of genetic shame strapped to my back like a tortoise shell, or would I release it to the waters of time?

Treyf is a story of grief and love, longing and forgiveness, of ultimately finding peace in a world laced with hope, the forbidden, and the eternal yearning for acceptance. There is a considerable amount of food in it — my beloved paternal grandmother fed me a cold, boiled brain on a plate the day after I saw the premiere of Young Frankenstein at The Ziegfield in 1974; all I could think of was Abby Normal. In Treyf, food is the grounding wire and the anchor; it is the silent collaborator in the story, the one who watches the tribe increase and the decades unspool and the rules be broken, repeatedly; food lures and betrays, beckons and soothes, and connects the present to the past in an unending loop.

To write memoir is to smell and taste and see things that exist only through a veil of memory and the specter of time. The risk is profound, and requires such focus that it’s very possible to lose the present, the here and now, while you’re busy trying to understand how you got here. The present becomes as much a ghost as the past; you wind up living in neither.

I incinerated the chicken because cooking is meditation; it requires — demands — full presence in the here and now, the gap between what was and what will be. And as anyone who writes memoir will tell you, it is an act that leaves you raw and a little bit shaky and discombobulated. In writing Treyf, I reached out across the decades and reacquainted myself with the thing I once was — the teenage misfit, the outcast, the one who scribbled notes in piles of composition books while the fondue party raged in the next room — unable to cook, to feed myself, to make sense of the world, and ravenously hungry for the future to arrive.

The writing is done now, and I’m stepping back into the kitchen to begin again, to start again, to feed myself and the people I love with presence and care.

How to Cook a Hard Boiled Egg

These days, there are many on-trend ways to cook an egg: there’s the seven-minute egg (very nice in ramen), the poached egg (excellent on buttered toast or atop a pile of wine-braised black lentils), or the scrambled egg (which tends to be overcooked to the consistency of, as Laurie Colwin once described it, an asbestos mat). I’m starting here because this is my nursery food; I make it when I’m in need of (no pun intended) coddling and a quick hit of protein. There are as many ways to cook a hard boiled egg as there are cooks, but this method has never failed me. If you’re cooking for a crowd, increase the number of eggs, the amount of water, and the size of the pan exponentially; the method and timing remains the same.

Makes 2 hard boiled eggs

Place two not-fresh eggs (2 weeks old is ideal) in a medium saucepan large enough to allow water to circulate around them. Fill with water to cover the eggs by an inch. Bring to a boil over medium high heat, slap a cover on the pan, and immediately remove it from the burner. Let it rest, covered, for exactly 12 minutes. Drain the water and run cold tap water over the eggs for exactly 1 minute. Drain, peel, and eat, sprinkled with Maldon sea salt, or even better, dukkah.

May 13, 2016

An excerpt from my new memoir, Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw

I’m excited to announce that my new memoir, Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw, will be released on September 20th, 2016, and is available for preorder. I’ve gotten scores of requests for a sneak peak from many of you. Please enjoy this small taste of Treyf:

From the Prologue

Fleishig or milchig?

It is 1995.

A middle-aged Hasidic antiques dealer on Second Avenue opens a splintering mahogany box and removes a tarnished silver serving set: a knife, a fork, a spoon.

We stand face-to-face in our respective uniforms: me, in paisley Doc Martens boots and a pilling, mauve Benetton sweater with broad, rounded shoulder pads that make me look a fullback. He, in sober black pants, black vest, black shoes, black suede yarmulke, and a white-on-white, chain-patterned shirt stained with the sweat of devotion, his tzitzit—the fringes of his prayer shawl—dangling beneath his fingers. A plume of graying black hair cascades up and out of his collar.

“It’s very nice,” he says, holding the fork up to the light streaming in through the windows, “but I see this pattern a lot. It’s from the Kennedys.”

After dating for five months, my parents married in 1962. My father was sure he had found the love of his life, and his future; my mother was sure she had found a way out of her parents’ house, and her future.

They were both right, and they were both wrong.

I was born nine months later, almost to the day. My father tells me this story for years, from the time I am old enough to understand what the words mean, and probably even before: that I was conceived on their wedding night, hours after their ceremony was presided over by Rabbi Charles Kahane—father of Jewish Defense League founder and crackpot firebrand Meir, murdered in 1990—and the kosher reception held at Terrace on the Park, overlooking the sinkhole that was Flushing Meadows, site of the World’s Fair two years later.

“It all happened very fast,” my father explains.

Before he married my mother, my father was engaged five times, each time to a woman his family deemed unacceptable.

“Treyf,” his mother said to me as she recounted the story, tipping her chin in the air and rolling her eyes: one was too big, another too short, another cross-eyed, another crazy, another not Jewish.

Treyf: According to Leviticus, “unkosher and prohibited,” like lobster, shrimp, pork, fish without scales, the mixing of meat and dairy. But also, according to my grandmother, imperfect, intolerable, offensive, undesirable, unclean, improper, filthy, broken, forbidden, illicit, rule-breaking.

A person can eat treyf; a person can be treyf.

“And then,” my grandmother said, “he met your mother.”

She folded her arms across her ample breast and heaved a long sigh.

My mother.

My tall, blond, fur model, television singer mother who I watched as men tripped over themselves to get to at the 1960s and 1970s Queens, New York, parties of my childhood.

When she met my father, a sack-suited, wing-tipped ad man specializing in postwar Long Island real estate, she had recently ended a relationship with the composer Bernie Wayne. Somewhere between Bernie and my father, there was someone I will call Thomas, a tall, Jewish, French-speaking, Sorbonne-educated beatnik who had purportedly once lived with Nina Simone, and whose diamond-dealer father had been knighted by the king of Belgium. When I was ten, my parents brought me along to one of Thomas’s legendary Saturday night Upper East Side cocktail parties, where I careened around the crowded apartment from table to table like a pinball, narrowly dodging the suede-patched elbows and lit Gitanes of the other guests. Invisible and unsupervised, I managed, just as the party was getting underway, to eat an entire block of pâté de campagne, a bowl of cornichons, and a round of stinking, oozing Époisses. An hour later, I writhed on Thomas’s bathroom floor like a snake and was comforted by some of the other guests while my parents went to get the car: the Hollywood Squares comedian David Brenner, who lived across the hall, rubbed my back; two hookers wearing matching black vinyl thigh-high platform boots and crushed purple velvet hot pants sang me a folk song with a cheap nylon-string guitar that one of them had brought along; and a long-haired man who claimed to be the drummer for Chicago scratched my head like I was a puppy. Forty years later, I can see the black-and-white octagonal tiles on Thomas’s bathroom floor, and I can feel the stiff nylon weave of the polyester shag rug burning my neck.

“Treyf,” my mother’s mother, Gaga, whispered to me as she mopped my forehead the next morning, while my parents slept soundly in their bedroom across the hall.

After their wedding ceremony, after the blessings were made by my paternal Grandpa Henry, a fire-and-brimstone Orthodox cantor, after the chopped liver was eaten, the gefilte loaf sliced, the Manischewitz Heavy Malaga poured and the hora danced, my parents drove to their honeymoon at the most modern of the upstate New York kosher borscht belt hotels, the Nevele, with their silver serving set locked in the trunk of their rental car. They had made it; they were finally legitimate. They had stepped on the glass, jumped the broom, leapt the chasm between freedom and conformity, adolescence and adulthood; they had done exactly what was expected of them.

Every member of my father’s family had the same set of silver—a Gorham service in the Etruscan Greek Key pattern—as if it was a shining periapt acknowledging their validity and confirming their eternal place in the clan. As a young child, I was regularly seated on a beige vinyl kitchen stool near the sink, while Gaga methodically polished the pieces; the process hypnotized me, and I watched without blinking how she tied a silk paisley kerchief around her nose and mouth like a bandit on Bonanza, poured the thick, pink Noxon onto a soft rag and massaged each utensil until it shone, silver and glowing and bright as a pearl. I was mesmerized by the pattern’s simplicity, and would hold the tarnished spoon on my lap and trace the design with my tiny index finger: it was nothing more than a straight line that flowed forward, then reticently coiled back on itself. It turned and moved forward again, repeating over and over without end. My father’s family didn’t arrive at Ellis Island from the old country with a family crest, and so we adopted the Greek Key as our own; it became ubiquitous, gracing everything from the edges of our linen tablecloths to our bath towels to the border around the hood of the English Balmoral pram my parents pushed me around the Upper East Side in when I was an infant.

A gift to my parents from my father’s sister and her husband and his sisters, the family silver bore witness to every tribal event that took place in our home from the early 1960s into the 1970s: tense Mother’s Day brunches and prim Thanksgivings. Funeral luncheons and birthday parties crackling with rage. It graced a decade of sweet Rosh Hashanah tables, prawn-filled cocktail parties, solemn shivas when well-meaning Catholic neighbors carried in trays of cheese-stuffed shells floating in meat sauce; holiday parties where bacon-wrapped water chestnuts and party franks were served with potato latkes; and Yom Kippur breakfasts where we set upon platters of sable and lox like a drowning man grabs for a life preserver.

When the parties were over, the only things remaining were invisible coils of gossip and the ancient family furies—the confidences breached, the grudges held, the forbidden flaunted and waved like a victory flag—that were spoken of in hushed tones and hung in the air like crepe paper streamers. Gaga waited until the last guest departed, plunked me down on the stool next to her, dumped the silver into the sink, and I watched in silence as she scoured away any trace of what had been eaten and what had been whispered, rendering it perfect and clean and kosher for the next occasion.

“So nu,” the Hasidic man says to me again, pushing his black plastic glasses up the bridge of his nose: “Do you know? Fleishig or milchig?”

Meat or dairy?

If I can assure him that the silver had been used in a devout home, where separate sets of plates and silverware are restricted for dairy and meat dishes, he won’t have to go to the trouble of koshering it for a Jewish customer wanting to buy it. He won’t have to put the set through the lengthy process of hag’alah—boiling the pieces while keeping them from touching each other so that every bit of the silver is exposed to the cleansing promise of the water, like baptism in a river.

I don’t know what to say, given all the years of meat lasagnas and pork dumplings and shrimp cocktails that the silver has served during my parents’ ill-fated marriage. After sixteen years, their relationship ended in the late 1970s, not in a modern Manhattan divorce court like in Kramer vs. Kramer, but in front of a beth din—a quorum of three Orthodox rabbis—who agreed, after some Talmudic debate, to grant them a get, a kosher document of marriage severance from husband to wife dating back to the days of Deuteronomy, and without which even the most assimilated Jewish couple, having gone through an American divorce court, is still considered married according to Talmudic law.

“Aha,” he gasps, holding up the knife, flecked with a tiny, hardened drop of dark red jam. He removes his glasses, holds his jeweler’s loop up to his eye, and confirms it with a combination of Talmudic reasoning and authority: “We don’t eat jam unless it’s with blintzes and blintzes are dairy. Therefore, he proclaims triumphantly, milchig!”

The last time I saw my parents’ silver serving pieces in use was when I was ten, the night of my father’s fiftieth birthday in 1973 during an ice storm—the ice storm; the Rick Moody–Ang Lee ice storm when New York nearly came to a standstill—when the delivery boy from the local deli couldn’t get his truck up the street to drop off the trays of food that my mother had ordered for what was supposed to be a grand surprise party. It was a bust; there was nothing to eat. Grandpa Henry called just as we were all starting to hide behind my parents’ black silk couch, and I jumped up to answer the phone. My father walked in, exhausted, his Harris tweed overcoat caked with melting slush, his woolen driver’s cap wet and dripping, and everyone yelled “Surprise!” and my grandfather said that he wouldn’t be there because it was the Sabbath.

“Tell him for me I’m sorry, Elissala dahlink,” he said in his thick Yiddish accent, and then he hung up.

“He always goes to all your sister’s parties,” my mother snarled, “whether it’s Shabbos or not.” She pulled him into their bedroom where they fought behind closed doors while the hungry neighbors downed glasses of scotch and I raided the fridge and produced a beige melamine platter of overlapping sliced salami, intermarrying the Oscar Mayer with the Hebrew National like a Unitarian Venn diagram. I put it out with a jar of Gulden’s mustard and half a loaf of my mother’s crumbling Pepperidge Farm diet white bread that I judiciously sliced into points, the way I had once watched Julia Child do on television. With no sign of the deli boy, the neighbors left and returned with whatever they could exhume from their refrigerators and cupboards: Polly from across the hall made Jell-O salad with cubed lemon-flavored Brach’s marshmallow Easter bunnies unearthed from the bowels of her candy cabinet. Carole from two flights up defrosted a pound of chopped meat under a waterfall of steaming bathwater and made Swedish meatballs with a container of milk she procured from the vending machine in the basement. My mother’s best friend, Inga, came back with a small boneless ham that she had basted with glaze under high heat until it resembled an overgrown Halloween candy apple. By seven o’clock, I pressed my ear to my parents’ bedroom door, and the shouting had slowed—they were spent and exhausted—while my father’s boss was on his fifth Dewar’s and playing my little wooden bongo drums in the living room while freezing rain pelted our windows. Wearing a fez and with his shirt unbuttoned to his navel like Tom Jones, my father’s best friend, Buck, hacked at the ham’s candy coating with the tip of the silver knife while Harry Belafonte’s Zombie Jamboree played in the background. We all gathered around while my father sliced his birthday cake, which was decorated like the real estate advertising pages of the New York Times and had been sitting on our terrace in the December cold for the better part of a week.

Twenty-two years later, I stare out the window of the antique shop, watching the traffic barrel down Second Avenue. I can taste the gummy Swedish meatballs thick with curdled milk and the Easter bunny marshmallows in the Jell-O salad. I can smell Buck’s Paco Rabanne, and see him in his Glen plaid Sansabelt trousers, chipping away at Inga’s candy apple ham. The antique dealer will never know that the little speck on my parents’ wedding silver set is not jam, but a stray bit of petrified pork glaze, hardened when my parents were still married and Nixon was still in office.

My father liberated the silver set from my mother right before their divorce, before she had a chance to change the locks; he kept it for me for fourteen years, hidden away deep his mother’s walk-in closet in Coney Island, next to an ancient bottle of Slivovitz and a shopping bag stuffed with photos of long-dead cousins from the old country, taken right before the Nazis marched in.

“So you just took it?” I asked, when he guiltily came clean about it one Saturday when I was sixteen, during his parental weekend visitation. We were having dinner at the Praha Restaurant in Manhattan, and he was nursing his second Gibson and poking at a plate of warm, apricot-stuffed palascinta. It was a bitterly cold night; ice rimed the windows like a frozen beer mug.

“She’d hock it if I didn’t—” he said, his eyes red and pleading, “and then you’d never know who you are. I’m keeping it safe and sound until you get married; then, it’s yours.”

After I lied for years whenever my mother went on a tear about her missing silver serving pieces—“You know, don’t you?” she’d say to me; “You know that he stole them, you’re protecting him,” her brown eyes fierce with rage—my father handed it over to me unceremoniously when I turned thirty after I told him I preferred women to men.

“No use in waiting anymore, then,” he said wistfully, stroking the mahogany case. He turned and walked out, leaving me standing alone in the middle of my tiny studio apartment, cradling the purloined box in my arms like an infant. The premarital giving of the family silver set marked me both as an adult, the family’s most ardent rule-breaker, and the family’s certain failure; I would never marry a man, and the traditional handoff on my assumed wedding day—what I was taught as a child would be a big affair at a country club on Long Island with a tall white multitiered cake and my Aunt Sylvia dancing a Russian sher—would never happen.

“Who do you think you are, to cheat us out of joy, to break the chain?” Aunt Sylvia whispered to me quietly in her kitchen the Thanksgiving after I came out, when I helped carry in plates from her table.

“I don’t know,” I said

And I didn’t.

I had no idea who I was.

For almost two years, the silver pieces sat hidden and covered in a blanket of on the bottom shelf of my television armoire, tucked behind a stack of ancient VHS tapes. I opened it only on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, when WQXR’s simulcast of the Kol Nidre services from Manhattan’s Temple Emanu-El began at sundown. The cantor chanted and I opened the box and released an angry Pandora: a musty, acrid pong rushed out of it like a wave and wrapped itself around me. The smell of the past—a gamey, transportive scent of despair and schmaltz and Aqua Net—made me woozy. I’d close the lid quickly and put the box back where I’d hidden it, complicit in my father’s pilfering, and where my mother would never find it.

The Greek Key signified our wandering path, our twisting course, our constant searching and moving forward while always turning back. It was a pattern of repetition; a tether to the past.

“Without it,” my father warned when he handed it over, “you’ll never know who you are.”

*

Advance Praise for Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw

“A brave and generous memoir, a lucid love letter to her own family’s history that…does the work of a great memoir in piercing the reader’s separateness, and reminding us that we are not alone. I love this book.”—Dani Shapiro, author of Devotion

“Treyf is a beautiful, brilliant memoir filled with striking images, unforgettable people, and vivid stories. Elissa Altman has given us the story of an era and a tribe, rooted in 1970s New York City, and wrought with such visceral love that the pages shimmer.”—Kate Christensen, Author of Blue Plate Special

“Treyf is a memoir that reads like a novel, a spellbinding portrait of a very specific world that also serves as a universal primer on identity, on loneliness, on the nature of familial bonds, on the ways we make sense of the mess of our lives. Gorgeous, singular, heartbreaking, haunting.”—Joanna Rakoff, author of My Salinger Year

“Savvy, warm hearted, and profoundly illuminating…The meaning of the forbidden—in a family, in a self—and the human needs we all struggle with are gloriously explored. This is a transforming book, one of the most satisfying memoirs I’ve ever read.”—Bonnie Friedman, author of Surrendering Oz: A Life in Essays

Available for Preorder

March 30, 2016

On Writing and the Permission to Succeed

Interviewer: You mentioned getting permission to write. Who gave it to you?

Morrison: No one. What I needed permission to do was succeed at it.

In a Fall 1993 Paris Review The Art of Fiction interview, Elissa Schappell spoke with Toni Morrison about the writing life. Morrison talked about writing while holding down a full-time job as an editor, writing with small children in the house, writing as a woman, writing as a woman of color, writing about controlling one’s own characters (and not), writing about sex (It’s just not sexy enough.). Morrison talked also about the weapons of the weak: nagging, poison, gossip. And about permission to write, and permission to succeed at it.

I read those words, and had a sticky, squirmy reaction; I felt the way I do when I stand back and witness the horror of someone else’s undoing. It’s a tight kink in the stomach; a hard walnut in the throat. We’ve all been there, haven’t we: we’ve seen the speaker who loses the words. The young actor who blanks out on stage. The musician who forgets the chords. The writer — the food writer; science writer; academic; novelist; it doesn’t matter — blocked by fear. We wince. Who are they to even try, some whisper as we watch them tumble from their place. When it comes our time, we become that person, naked on the stage: doubtful, panicky, assured by the nagging, the poison, the gossipy gremlin chatter over our shoulders, promising that we too, will most certainly, most definitely, fail.

I have just spent the last eighteen months writing my next memoir; for a long while, I worked as a cookbook editor, and I wrote on the train in longhand scribbles, at night in my pajamas, during lunch breaks, on the weekend, until it became clear to me that it I had to step away from one job or the other. After much domestic hand-wringing, the decision was made: I relinquished my position tearfully — I loved it and was good at it; I had long ago been given permission to succeed at being an editor — and went home to my office and closed the door, and wrote. I did what all the books and my writing teachers say you’re supposed to do: I put my ass in my chair every morning at 8:30, and apart from doing yoga a few times a week, walking the dogs, and making myself endless cups of tea, I didn’t move. Some days the work flowed like a river; some days I stared at the page — each word I managed to eek out was like squeezing the back end of an elephant through the eye of a needle — and wept. Alone. And I asked myself the same thing I did while I was writing my first memoir: Do I have the permission to succeed at this? Who am I to tell my stories?

Who are you to not tell them, a writer friend said to me. This writer friend — there are novels, memoirs, a short story collection — tells me that it is ownership, the acceptance of the fact that our stories make us who we are, that is the most complicated and treacherous part of what we do. When that ownership is withheld, we cannot succeed. When other forces say no, that story is not yours, they have not only killed it and its place in your soul; they have killed you.

There are plenty of hurdles in the writing process: distraction, diligence, envy, arrogance, dedication, time, space, money, nagging, poison, gossip. There is the seductive conceit that lures you, like an animal into a trap, towards the belief that your work is spectacular, whatever that means, long before your work is actually even done; there’s the quicksand of self-doubt so immobilizing that you can’t climb out of it, and the more you struggle, the deeper you get sucked in. Writing is balance. Mrs. Ramsay was right: A light here requires a shadow there. The hurdles can make you think you’re better-or-worse than: they can shut you down, prop you up, alter your course, tack your sails. They can result in moments of bliss and terror, calm and panic, hubris and humility, pomposity, paranoia, and paralysis. Often within moments of each other.

These obstacles may hinder permission to write, but they don’t withhold permission to succeed at it. That — the rickety, splintering plank connecting the two, as quavery as a rope bridge over a gorge — is reserved strictly for shame.

You don’t think shame, says Janna Malamud Smith. You feel covered in its viscose grime. The great hand immerses you whenever you are told you are, or believe yourself to be, violating a basic communal code.