Anna Vaught's Blog, page 16

September 12, 2016

People’s Book Prize

http://www.peoplesbookprize.com/section.php?id=6

Fiction

Non-Fiction

Children

Publishers

How to Vote

Rules of Entry

Sponsors

Press & PR

Finalists & Winners

FAQ

Follow us

Tell a friend…

Patron:

Frederick Forsyth CBE

Founding Patron:

Dame Beryl Bainbridge DBE

23 Berkeley Square

London

W1J 6HE

020 76656605

admin@peoplesbookprize.com

Read an extract…

Buy this book :

Paperback

Ebook

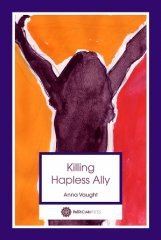

Killing Hapless Ally

By Anna Vaught

Published by Patrician Press

ISBN 978-0-9932388-6-4

Category Humour

Autumn 2016 (Sept – Nov)

Synopsis

This is a black comedy in which young Alison conceived an alter ego ‘Hapless Ally’ to present a more palatable version of herself to her family and others. Ominously, the alter ego began to develop autonomy. Alison deals with this helped by a varied catalogue of imaginary friends.

Author’s Biography

Anna is an English teacher, mentor and tutor for young people, copywriter and freelance journalist; she has self-published two previous books, been a volunteer nationally and internationally and now writes poetry (to be published by The Emma Press this autumn and Patrician Press in the spring), as well as working on a new novel and some short stories. Anna is also a mental health campaigner and advocate and the mum of three young boys.

Reviews

Contemporary Small Press May 2016 https://thecontemporarysmallpress.com/2016/05/04/darkly-funny-and-courageous-killing-hapless-ally/

Amazon (link as above) 7 Reviews

Price £10.00

Liked my debut novel, Killing Hapless Ally and want to offer a vote for it? Here’s a link.

Anna xxxx

September 1, 2016

The Life of Almost

Ah, I struggle with a synopsis, but here you go. THE NEXT (alongside the other stuff).

This is for you, Alex Campbell. x

Anna Vaught

The Life of Almost

or,

A Life Of Very Little Expectation

A synopsis

The Life of Almost is a re-working of the story in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, shifting its setting to a wild, mysterious and comical rural South West Wales, the West Country and the suburbs of London. Some characters are based on those found in its stimulus, but others are original —such as Evans the Bodies, keeper of the mortuary and devoted to his Dead Dears. And Muffled Mfanwy, who works with him and with whom Evans has been in love his entire life; their story in startling surroundings is a counterpoint to other love stories in the book, such as that between Almost and the cruel Seren, adopted daughter of the claw-handed spinster Miss Davies, at Clandestine House off the sea coast on the Cleddau Estuary.

Almost is a boy with poor beginnings, who begins his life shrouded by bereavement, the struggling, the bitter and those on the run from the law and from life; he is also surrounded by the hauntings of the undead of his family and the cliff-top communities around him. He plays in the sea caves, visits graves, like Pip, sings into the sea and likes to tell stories—and telling stories is a key theme of the book. Many strands of the narrative I took not from Dickens but from the oral tradition of my large Pembrokeshire family, such as accounts of poltergeists throwing furniture and vases from the fireplace, gibbering dead and moss that caught your foot and sucked at you if you didn’t move quickly enough; things that enthralled and terrified me as a small child. The drownings, skewerings and disappearances that have always rattled in my imagination find form in The Life of Almost.

Almost is dragged up by his sister Perfection, both of them kept in their place from beyond the grave by their mother and grandmother. Almost cries with the name his late mother gave him because he feels he will never amount to much, but gradually he begins to realise that, by calling to the world around him and by telling stories, extraordinary things begin to happen. For Almost is, really, an extraordinary boy.

Almost has, like Pip, a secret benefactor and a true love; he has his own convict and a cruel sister, but this re-working of the story adds more spectral, supernatural elements and more comedy in that Almost, through his story-telling develops the gift of moving through time and through form so as to come and rescue others from suffering, hardship and the loneliness of loss. It is at this point, at the beginning of the book, where we meet him, when as he appears to Catherine who begins the story, sitting, lost and stifled “in the squalid summer of 2016”.

Almost is supported by his devoted mermaids, Dilys and Nerys, who follow him, changing form (I have drawn on extensive mermaid lore in my research for the book), and by a number of friends in different locations. But readers of Great Expectations, would recognise adaptations of characters, such as Pip’s friend, Herbert Pocket, Miss Havisham, Estella and Jaggers (the latter, for example, recast as a lugubrious but prosperous journeyman, basking in his gold and quoting Jonson’s Volpone from his gated community a long way from Almost’s Pembrokeshire!).

I have allowed some risk-taking with the novel’s form in its use of original poems as epigraphs, all of which key in to the themes in the novel, as they describe the dark vagaries of the Welsh landscape, which is itself a key character in the book, living and breathing and casting penumbra and surrounded by the sea. I have also offered two endings to the love story in my book because I wanted to bring to mind how Great Expectations might have been radically altered in its reception, had Dickens been encouraged to use his original ending, far more melancholy that that which replaced it.

August 28, 2016

Violet Gibson and Lucia Joyce. A little piece I’ve begun working on.

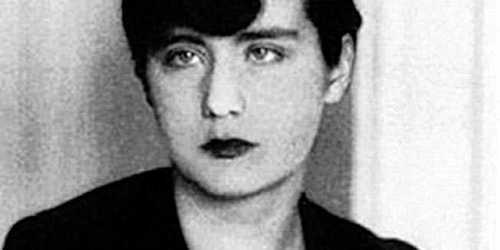

Violet Gibson was the daughter of an Irish aristocrat; she shot and wounded Mussolini, was briefly imprisoned and then sent to St Andrew’s Infirmary (a psychiatric hospital which today is Britain’s largest), near Northampton; Violet died there in 1956. Lucia Joyce was the daughter of the novelist, James Joyce. She, too, was committed to St Andrew’s (in 1951) and remained there until the end of her life, in 1982. We have very little information about her time there and letters, pictures and records held by the estate were destroyed.

The two women are buried near each other in Kingsthorpe cemetery, Northampton. We do not know anything which passed between the two women, although it is not unreasonable to think they may have met, so the story imagines how it might have been and was stimulated by the one picture of Violet Gibson in St Andrew’s which remains (there are none of Lucia): a delicate and elderly looking lady, in a winter coat, feeding the birds from her hand as she stood in the garden of the hospital. It made me cry. I am myself a long-time sufferer of mental health problems, so when I cried it was because I thought perhaps Violet and Lucia could have been better; been free. As birds.

What follows is a little extract from a short story I have drafted…who do you suppose the ‘He’ is?

And then the universe was not malicious; it was at worst benign, maybe laughing and with us, not at us, life, death and other tuppenny aches. The fuss, the both and trouble. So I was looking at my bed, tonight, St Andrew’s not the garden in Ireland (oh but of course you knew) and seeing a counterpane above the boiled grey blankets, felted with the hard wash and the stretched linen corpse sheets. I hate them beyond expression and into silence. But I am being bad. I promised to be a good girl. You know, they could have hanged me, out there, in there; instead this incarceration and boiled wool beds and corpse linen. But Il Duce, grazed by my bullets, he thought he would live forever. I thought of Ozymandias, trunkless legs lost to sand and a wind-blown inscription.

They hung the man up by his heels, the man I shot, why I was here.

He never expected that.

Look, I survived him.

Tomorrow.

I promise.

**********

Night passes. Nightingales; shrieks and screams and an administering.

The night doctor is called, grey from sleep.

Rattle-bags and tired bones. Unintended forevers.

Today.

**********

‘I have decided I must talk more to Lucia and I will do something for her. I heard whispers from the walls. I am not supposed to know. It’s said that she has been rubbed out. Her letters gone; records destroyed, gone to dust. No-one speaks of her. If Nora came, I didn’t see her. If He came, I couldn’t say, although perhaps only once and that perfunctorily. That was what I heard. No—not from the birds, if that was what you thought: from the nurses’ bird chatter. And if He came, He never came back.

Everyone has forgotten her. She had no gun. It is not right. I want to give something to her.

I creep.

She says this.

‘Father said my body would not could not dance. He was a genius, I know, they say, they know. He said I was good, I wanted ballet, but my body was stiff and cold; I couldn’t do. So he said; so he told them. I left. Draw, write. The Wake. The talk between us. It wasn’t so much; just knowing: nods and sighs; a sort of creole. But not so much. I murmured and said I wanted something that was mine but he wanted to look after me. Mother did not come again, not after the first time. There were men, before, there was Him. Also genius. He saw the world for what it was: bad tallow and ashes but oh my father said differently: that the reach of man, if he knew, if he let, if he thought, could extend out there into the universe.

But did you know Him, in Ireland, or was He gone to Paris then?’

Her gutturals like furrows.

She is not like us; not one of us. But she is interesting, is she not?

And it is not fair, what they have done. They made her not exist, out there.

‘He refused me. I suppose others know. Not about me, about Him, He would be, must be famous now. Violet. I promise I will not shout and I do not have fire. I am so alone, lonely. You should not be here. This is our punishment, making us well, not or maybe. I cannot think. I cannot make it go in straight lines or proper lengths.’

Gutturals like furrows.

Thoughts run rivulets and turn, as they should not.

Lucia cries, as she always does. I cannot because there is no cry left.

And I think that cry is cry and all that can matter is that it should stop.

He cried in pain, he cried to laugh, to mock and they strung him up by his heels.

Now that was fair.

‘Come with me, Lucia.’

‘It is forbidden.’

‘What is the worst they can do? We are already bound over, in this forever place.’

‘But don’t you think He will come for me?’

(The photo here is of Lucia Joyce; the featured image that of Violet Gibson, in the grounds of St Andrew’s.)

August 6, 2016

Not the Booker, 2016

So…if you have read and liked my debut novel, Killing Hapless Ally, and it meant something to you; if it made you laugh; you thought it had weight; if it made you fall madly in love with Albert Camus or understand what mental health problems or mental illness might be like (my publisher makes it clear at the beginning of the book that I drew on many episodes in my own life; if you like semi colons, Dolly Parton, poetry and laughing at the dark things…go on, vote for it. The article that follows is from ‘The Guardian’ and below is the link you need to click on, register with ‘The Guardian’, then offer your vote. Actually, there should be two votes, but you need only comment on one of the books.

And look at all those indies! What follows, then, is from ‘The Guardian’; just underneath it, I’ve copied my votes.

**********************************************

Not the Booker prize (very) longlist 2016: votes, please!

If you felt this year’s Man Booker selection was not broad enough, get a load of ours. And help decide which books make the shortlist

A very small sample of the authors on our longlist … (clockwise from top left) … Julian Barnes, Don DeLillo, Kei Miller, Sarah Perry, China Miéville and Lionel Shriver. Composite: Alamy/Rex/Getty Images/Graham Turner/Graeme Robertson/Sarah Lee for The Guardian

Save for later

Last week the Man Booker longlist was announced. A little surprising, right?

OK, I’m happy to admit that the main prize has a few things going for it. But I always feel that its longlist is just as notable for its omissions as the books that are chosen. This year was no exception. A few good books sometimes sneak on there – but dozens more don’t make it. And you know what? The Booker’s so-called longlist isn’t even that long. Not like the Not the Booker. As you will see below, our list really is long.

There are well over 100 books, making 2016 a record year already. So thank you to everyone who has contributed so far. And I hope you stick around as the real work begins. Because we somehow have to whittle this mighty list down to a manageable half-dozen books.

And how do we do that? We vote! If you want to take part, all you have to do is choose two books from the longlist, from two different publishers, and accompany those votes with a short review of at least one of your chosen books. It would also be very helpful if you included the word “vote”.

The review should be something over 100 words long, although as our glorious and shining Terms and Conditions state, we won’t be counting that carefully. Just make it look like you care.

Sign up to our Bookmarks newsletter

Read more

It’s that simple. So let’s get voting. You’ve got just over a week. The deadline is 23.59 on 14 August 2016. The contenders are:

Megan Abbott– You Will Know Me (Picador)

Lesley Allen – The Lonely Life of Biddy Weir (Twenty7)

Deborah Andrews – Walking the Lights (Freight Books)

Louis Armand – The Combinations (Equus)

Kate Armstrong – The Storyteller (Holland House)

Jason Arnopp – The Last Days of Jack Sparks (Orbit)

Jenn Ashworth – Fell (Sceptre)

Chris Bachelder – The Throwback Special (WW Norton & Company)

Jo Baker – A Country Road, A Tree (Doubleday)

Julian Barnes – The Noise of Time (Jonathan Cape)

Shirley Barrett – Rush Oh! (Little, Brown)

Kevin Barry – Beatlebone (Doubleday)

Louise Beech – The Mountain in My Shoe (Orenda)

Claire-Louise Bennett – Pond (Fitzcarraldo)

Bill Beverly – Dodgers (No Exit Press)

Lochlan Bloom – The Wave (Dead Ink)

Lisa Blower – Sitting Ducks (Fair Acre)

Megan Bradbury – Everyone Is Watching (Picador)

Caroline Brothers – The Memory Stones (Bloomsbury)

Liam Brown – Wild Life (Legend Press)

Rowan Hisayo Buchanon – Harmless Like You (Sceptre)

Tom Bullough – Addlands (Granta)

Paul Burston – The Black Path (Accent Press Ltd)

Jackie Buxton – Glass Houses (Urbane Publications)

Louise Candlish – The Swimming Pool (Penguin)

Joanna Cannon – The Trouble With Goats and Sheep (The Borough Press)

Emma Chapman – The Last Photograph (Picador)

Anna Chilvers – Tainted Love (Bluemoose)

Dan Clements – What Will Remain (Silvertail)

Clár Ni Chonghaile – Fractured (Legend Press)

Chris Cleave – Everyone Brave Is Forgiven (Sceptre)

Emma Cline – The Girls (Chatto & Windus)

Paul MM Cooper – River of Ink (Bloomsbury)

Mark Connors – Stickleback (Armley Press)

Isabel Costello – Paris Mon Amour (Canelo)

Jack Cox – Dodge Rose (Dalkey Archive Press)

Justin Cronin – The City of Mirrors (Orion)

Rachel Cusk – Transit (Jonathan Cape)

Shelley Day – The Confession of Stella Moon (Contraband)

Don DeLillo – Zero K (Picador)

Ruth Dugdall – Nowhere Girl (Legend Press)

Sophie Duffy – Bright Stars (Legend Press)

Ken Edwards – Country Life (Unthank Books)

Jo Ely – Stone Seeds (Urbane Publications)

Guillermo Erades – Back to Moscow (Scribner UK)

Pamela Erens – Eleven Hours (Atlantic Books)

Lyn G Farrell – The Wacky Man (Legend Press)

Julia Forster – What a Way to Go (Atlantic Books)

Harry Gallon – The Shapes Of Dogs’ Eyes (Dead Ink)

Ruth Gilligan – Nine Folds Make A Paper Swan (Atlantic Books)

Jules Grant – We Go Around in the Night and Are Consumed By Fire (Myriad)

Guinevere Glasfurd – The Words in My Hand (Two Roads)

Garth Greenwell – What Belongs to You (Farrar, Straus and Giraux)

David John Griffin – Infinite Rooms (Urbane Publications)

Michael Grothaus – Epiphany Jones (Orenda Books)

Lee Harrison – The Bastard Wonderland (Wrecking Ball Press)

Adam Haslett – Imagine Me Gone (Little Brown and Company)

Noah Hawley – Before the Fall (Hodder & Stoughton)

Matt Hill – Graft (Angry Robot)

Catherine Hokin – Blood and Roses (Yolk Publishing)

Anna Hope – The Ballroom (Doubleday)

Michael Hughes – The Countenance Divine (John Murray)

Dave Hutchinson – Europe at Midnight (Solaris)

Amanda Jennings – In Her Wake (Orenda Books)

Elnathan John – Born on a Tuesday (Cassava Republic)

Anjali Joseph – The Living (Fourth Estate)

Avril Joy – Sometimes a River Song (Linen Press)

Mireille Juchau – The World Without Us (Bloomsbury)

James Kelman – Dirt Road (Canongate)

Claire King – Everything Love Is (Bloomsbury)

Hannah Kohler – The Outside Lands (Picador)

John Lake – Amy and the Fox (Armley Press)

Jem Lester – Shtum (Orion)

Ashley Lister – Raven and Skull (Caffeine Nights Publishing)

Carol Lovekin – Ghostbird (Honno Welsh Women’s Press)

PK Lynch – Armadillos (Legend Press)

Martin MacInnes – Infinite Ground (Atlantic Books)

Kevin MacNeil – The Brilliant and Forever (Polygon)

Seraphina Madsen – Dodge and Burn (Dodo Ink)

Brooke Maganti – The Turning Tide (W&N)

Ayisha Malik – Sophia Khan is Not Obliged (Twenty7)

Michael J Malone – Bad Samaritan (Contraband)

Iain Maloney – The Waves Burn Bright (Freight Books)

Sarah Ladipo Manyika – Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun (Cassava Republic Press)

Alex Marwood – The Darkest Secret (Sphere)

Colum McCann – Thirteen Ways of Looking (Bloomsbury)

Tiffany McDaniel – The Summer That Melted Everything (Scribe)

Ian McGuire – The North Water (Scribner UK)

Elizabeth McKenzie – The Portable Veblen (Penguin Press)

Wyl Menmuir – The Many (Salt)

Sarah Meyrick – Knowing Anna (SPCK Publishing)

Dan Micklethwaite – The Less Than Perfect Legend of Donna Creosote(Bluemoose)

China Miéville – This Census Taker (Del Rey Books)

Kei Miller – Augustown (W&N)

Alan Moore – Jerusalem (Liveright and Knockabout)

Alison Moore – Death and the Seaside (Salt)

Claire Morrall – When the Floods Came (Sceptre)

Yelena Moskovich – The Natashas (Serpent’s Tail)

Sarah Moss – The Tidal Zone (Granta Books)

Sylvain Neuvel – Sleeping Giants (Del Rey Books)

Carl Neville – Resolution Way (Repeater Books)

Suzy Norman – Duff (Patrician Press)

Claire North – The Sudden Appearance of Hope (Orbit)

Barney Norris – Five Rivers Met on a Wooded Plain (Doubleday)

Edna O’Brien – The Little Red Chairs (Faber & Faber)

Paraic O’Donnell – The Maker of Swans (W&N)

Maggie O’Farrell – This Must Be the Place (Tinder Press)

Harry Parker – Anatomy of a Soldier (Faber & Faber)

Sarah Perry – The Essex Serpent (Serpent’s Tail)

Cherry Potts – The Dowry Blade (Arachne Press)

Laura Powell – The Unforgotten (Freight Books)

Christopher Priest – The Gradual (Gollancz)

Lucy Ribchester – The Amber Shadows (Simon & Schuster UK)

Mary-Jane Riley – After She Fell (Killer Reads)

Adam Roberts – The Thing Itself (Gollancz)

Lou Rowan – A Mystery’s No Problem (Equus)

Amanda Saint – As If I Were a River (Urbane Publications)

James Sallis – Willnot (No Exit Press)

David Savill – They Are Trying to Break Your Heart (Bloomsbury)

Anakana Schofield – Martin John (And Other Stories)

Helen Sedgwick – The Comet Seekers (Harvill Secker)

Lionel Shriver – The Mandibles (The Borough Press)

Karin Slaughter – The Kept Woman (Century)

Ethyl Smith – Changed Times (ThunderPoint Publishing)

Francis Spufford – Golden Hill (Faber & Faber)

Sarayu Srivatsa – If You Look For Me I Am Not Here (Bluemoose)

Elizabeth Strout –

Emma Claire Sweeney – Owl Song at Dawn (Legend Press)

M Suddain – Hunters and Collectors (Jonathan Cape)

Graham Swift – Mothering Sunday (Scribner UK)

David Szalay – All That Man Is (Jonathan Cape)

Jonathan Taylor – Melissa (Salt Publishing)

William Thacker – Lingua Franca (Legend Press)

Yusuf Toropov – Jihadi: A Love Story (Orenda Books)

Anna Vaught – Killing Hapless Alley (Patrician Press)

Dan Vyleta – Smoke (W&N)

Natasha Walter – A Quiet Life (The Borough Press)

Simon Wan – Love and a Dozen Roast Potatoes (Urbane Publications)

Eleanor Wasserberg – Foxlowe (Harper Collins)

Jemma Wayne – Chains of Sand (Legend Press)

Aliya Whitely – The Arrival of the Missives (Unsung Stories)

Chis Whitaker – Tall Oaks (Twenty7)

Hugo Wilcken – The Reflection (Melville House UK)

Matt Wilven – The Blackbird Singularity (Legend Press)

Charlotte Wood – The Natural Way of Things (Allen & Unwin)

James Yorkston – Three Craws (Freight Books)

I’ll be back here on 15 August to post the results – and no doubt feeling slightly frazzled from all the counting. Let’s go!

***********************************

And here are my two votes:

annaVaught

30m ago

My two votes. PK Lynch’s Armadillos (Legend). Aggie’s voice clear as a bell and has stayed with me; excellent, sustained narrative. Admittedly I did find elements of this difficult to read because of experiences I share with Aggie, but I am glad I kept going. One of the biggest compliments I can give to this book is that she has (and I want to qualify that I am a huge Faulkner fan and of Southern literature in general plus it’s my second home and I’m married to A Georgia Boy!) pulled off the voice, the vocabulary and the nuance, which is no mean feat and something I have seen done poorly elsewhere. The settings are haunting and there are elements of joy and humour in the blackness. It reminded me of a book that is too little known – Erskine Cauldwell’s God’s Little Acre – with its grisly portrayal of the characters PK has as ‘subs’. I think Armadillos is a skilfully written book and its prose is spare but allusive. At least, that is how it seemed to me! I felt I knew all along what the ending would be. Knew it inchoately. Didn’t spoil my enjoyment of the story at all. A familiar -oh yes- and beautiful book.

Book two. Duff by Suzy Norman (Patrician Press). Skilfully done; restrained prose; funny; love the journey and the landscape – its sweep of places, visited and remembered. It is sweet, sad and moving. I felt the rhythms of Dylan Thomas, prose and poetry, moving within it.

I’d love to discuss both these books with their authors. Both are debut novelists. Right, I am off to read A Country Road, A Tree, Solar Bones, The Blackbird Singularity and Sometimes a River Song…I am only sorry I cannot nominate more books. It has, for example, been such a brilliant year for smaller presses!

Anna

********************************************

July 30, 2016

To keep going…

I am crying a little bit here. But read on. It’s fine, really.

Do you know, I am nominated several times for ‘The Guardian’ Not the Booker prize, I am entered for the Goldsmith’s Prize, the new Republic of Consciousness Prize and The Wellcome Book Prize. I also put in a poetry pamphlet for ‘Mslexia”s annual competition.

Do I have a shot? Naaah, not really.

Well, frankly, only a tiny one, at best.

I’m small fry; I’m a newbie and pretty unrefined, still. I blundered into this in the same naive way I have blundered into most things in my life! I sort of…had a go when theoretically it wasn’t supposed to be possible with all my other commitments. I’m a hard worker because, I think, I have had so much experience compromised by mental health problems, illness and bereavement that it has made me more imaginative and keen to seize the day in case we are hit by an asteroid or I go bonkers again (which I am not planning to, obviously). If this is you too, be collected; be encouraged: you would be amazed what is possible and at the way which can be made from no way and from despair.

AND SOMEHOW

In two years, I have written and published a novel, a poetry pamphlet, guest blogged, authored ten articles or so and at this point I am approximately two thirds of the way through a second novel and have poetry and short story publication this autumn and in the spring. So HOLY F*** three kids and a day job and the volunteer stuff. I have to keep going now, don’t I?

On, blunder on. xxx

July 19, 2016

The Google Frog (by my five year old)

Bit of a departure here.

Yesterday, I found this little story which my five year old had written in bed. It is way better than anything I could do. Please forgive me any sentimentalism here. It’s the original spelling.

THE GOOGLE FROG

The frog saw googleplex fleas

The fleas sukt all his blud BUT THEN

They got batulism and they were poisond amytoontly.’

Like it?

July 18, 2016

Not The Booker Prize 2016

Super short post this! I was just reading the information on this:

And here is a wonderful thing, now in its eighth year. I am just about to place my nomination and I wonder: if you have read Killing Hapless Ally, my debut novel, and you liked it and it meant something to you, do nominate that, if you like!

Every year, the list gives you some brilliant reading. Say, a book that we might not otherwise have heard of and which turns out to be outstanding. Oh – there are a lot of writers out there. (Not to mention a lot of small but exceptional presses.)

Have a look? The picture featured is of the lovely mug that a writer might win!

Anna

July 15, 2016

‘Yes, Mfanwy: in the midst of life we are in death and here with the Dead Dears it is fair to say that we are in love.’

From The Life of Almost as I draft it…

And there was another book that had only been seen by its owner.

Evans the Bodies wrote poems. Often for the Dead Dears who had no-one and whose lives must, he thought, be recorded for posterity. So the timid lady from the post office, who had customers and bread but no friends and a mother who would have tossed her out with the peelings for the pigs, became a cowslip in a warm meadow and drank deep of the sun and was happy; so a coarse and crooked man, who lived in the last house before St Brides Bay and whose children hated him but sang like larks for his money, was limned as a quiet man, skimming stones on the beach and smiling into the auroras of a coastal morning when no-one knew. But Evans the Bodies was a watcher for the sad and lonely. He was a dresser of bodies, to be sure, but he also had a talent for the sad soul and the lonely. And alongside his careful stitch and suture and his eye for the sick at heart, he had always loved Mfanwy: when she was someone else’s, as she laboured for and lost her child, when both times he bought her milk-white lilies and she said, ‘Evans, there’s a soft man you are’ and he cried with his back to her, as he did when she lost her husband. He put poems in the book for her, too. Imagined he was taking pictures of her, watching her written into the world all around and, as he watched the frosty lines on the windows in his cold parlour and saw the feathers and curlicues of winter, he scratched her monogram in the frost and rime and, again, he cried, and saw himself at a window as the beautiful ship Mfanwy his Love sailed away and thus he wrote again.

I had seen the rapture and the writing called ‘Mfanwy’, of course, though he did not know. I had learned it by heart and whispered it into the Pembrokeshire night, whose kind tendrils carried it to her and caressed her, then softly laid waste to sadness and silence and made her think clearly about Evans the Bodies, who loved her and always had, just so.

July 11, 2016

The Life of Almost – and an invitation, if you’re local, like.

First a little extract for you. Then, afterwards, an invitation if you are a local-ish writer or reader and would like to come for some reading and discussion of the first few chapters of the book I am working on, my follow up to Killing Hapless Ally (March, 2016, Patrician Press).

The Life of Almost is a re-working of Great Expectations, with its protagonist, Almost, roughly modelled on Pip. It has a predominantly Welsh setting, much of it being in Pembrokeshire. As such, it draws on the stories I have been listening to my whole life and so I have adapted these for the book. Stories of sailors, the strange dangers of the sea and those who love in it and on it; dark events at steam fairs; predicaments at village shows; kelp, barnacles, tough salty men, the cree of the curlew and the dead across the estuary and of how gentry moved in and spoiled all. Stories of beatings known about but hidden in plain sight; curses and vendettas; strange harpists, madness, mutism; poltergeists who threw pictures from walls and plants from windowsills and vases from above the fireplace. People who went away and never came back: stories, stories, stories. Shootings, hangings, disappearances. My idea of a picnic could still revolve around sitting by graves describing the dreadful manner in which relatives died, except I desist because I’m the mother of three young boys and I think my upbringing was definitely weird and I’m sure the kids think I’m quite peculiar, already.

So, you know roughly the story arc if you know Great Expectations, I’ve told you a little of the settings, but there’s more to it. Because, as Almost takes you through stories of his world – as he tells them to Catherine, who opens the first chapter, so tired of life – you come to realise that he is not entirely of this world and not entirely of this time: he is something more protean and unconfined; a storyteller who can shift substance in an extraordinary way and who is not compromised by, shall we say, temporal and ordinal rules…I hope, when it finds its home, that you will find the book darkly funny, maybe a bit shocking in places and that you’ll enjoy what I have done with my favourite book, Great Expectations, such as reworked Jaggers into a nasty (Ben Jonson’s) ‘Volpone’, basking in his gold somewhere off a great motorway and given you many elements of the supernatural. I did something a bit radical the other day and incorporated, euphemistically, some of the Brexit scoundrels – they are part of why Catherine, who begins the book, is so jaded and sad and thus why she has Almost come to visit. And, you know, one might question: is Almost really there at all? Or is he created by others when….they need him. Oooohhhh.

Because I stand by this and know it to be true: a story can save your life.

What occurs below is part of an episode featuring Evans the Bodies and Muffled Mfanwy. Just as Great Expectations includes Pip’s love for Estella, The Life of Almost has a fractured and difficult love story between Almost and Seren, adopted daughter of Miss Davies the Dowager at Clandestine House on the Cleddau estuary. But not just between these two – also between Evans the Bodies and his beloved Mfanwy, a little piece of which begins below.

Chapter five. Dressing the Dead Dears

Evans the Bodies loved his Dead Dears. He had established a thriving business in the low white buildings out the back of a farm on the coast road. In the past, this had been owned by a rather careless and drunken farmer with an insecure barn so that, from time, those who arrived for Evans’s attention—silently, so silently—might have met with a stray cow crossing the yard or traversed cow pats, so hardly the most respectful of endings, or beginnings, as Evans saw it, since he was fonder of the dead than the living and saw things backwards through his better eye. Nowadays, though, the yard was gravelled, the whitewash immaculate, the cows tidily restrained and a new farmer in residence. This man was laughed at by the locals as a hobby farmer. A man with an antique shop in Tenby who got people in to do the hard work and exhibited his cheese to great applause, although he had not really made it himself and even his dairy herd looked askance, it was said on the coast road, because your dairy cow knew an amateur when it saw one and mocked in its cow-grunt.

So there, in his low white buildings, worked Evans. And I went to work with him when I was older; I was a poor schoolboy, so they farmed me out on an apprenticeship as soon as they could. Technically, I should have been eighteen to be allowed to handle the dead, but we hid from the rules, I looked big and talked confidently and bluffed expertly and then Evans—at least to begin with—kept me away from the worst, most gruesome cases. He needn’t have done, for I saw no fear in temporal things and the sad features of a face rearranged; I saw them as the anagram of thereafter. But as I was saying, I worked with him, learned from the master and saw how he attended carefully to his craft. He had it all planned meticulously and liked to recite the rules of his job to himself and declaim thus to the world, should it be listening. But the best of the words were not really for me, Catherine, but for the woman he had loved his whole life and whose own life and voice had been taken by the abruptly dead of her own.

For with him worked Muffled Mfanwy.

I mentioned her, to you, Catherine, in my list of characters. She went muffled after Philip Llewhellin hanged himself in the shed and then her son, Lewis the Younger, remember? Evans was in love with this quiet sad lady and together they worked with the corpses, a delicate ballet, with tubes and brushes and buckets and pipes and the love of the dead that is known best to those sad with the living, or those born, or otherwise, with their feet half in the next world. And I watched them in the twilight shadows, Catherine. Always I was there. Because he was lonely, even with his Dead Dears and she was sad and her voice was stilled and I wanted to give her flight and for her to sing and cast off her own dead.

Friday 22nd July, 10 am. A read through and discussion of the first few chapters of The Life of Almost, my second book – which I am currently drafting. It has to go off at the beginning of October. If you would like to come, DM me @bookwormvaught on twitter. I will do cake and tea, so just bring your listening ears and your critical voice (eg, well that bit was too weird/a bit shite/didn’t follow that bit/oh yes that was lovely etc etc) and DO be prepared for mermaids and – WARNING – some rather graphic bits about embalming and funeral practice (Almost’s trade).

Like a copy of Killing Hapless Ally? Order from Waterstones, your local bookshop (Ex Libris and Mr B’s have copies in our area), the Patrician Press website or Amazon here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Killing-Hapless-Ally-Anna-Vaught-ebook/dp/B01CA5F21Y/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1468239225&sr=1-1

June 30, 2016

A fine new anthology to come

Here’s a lovely thing. A beautiful new book from Patrician Press, who published my debut novel, Killing Hapless Ally. The book will be out in February and features some of our cohort (including a story from me!) and the work of those who entered short stories and poems in its attached writing competition. Patrician is dynamic and philanthropic. I think this will be a beautiful and timely book from the press. Its theme: refugees and peace-seekers.

Patrician Press Anthology of Poems and Short Stories

Published February 1st, 2017

Published February 1st, 2017Prices

£3.99 (e-book)

£8.00 (print)

ISBN

9780993494543 (e-book)

9780993494567 (print)

By Anna Johnson, Editor

This anthology of poems and short stories is the result of short-listed works from a competition Patrician Press ran in 2016 on the themes of Refugees and Peace-Seekers. The entries were judged by Joceline Bury, Anna Johnson, Emma Kittle-Pey and Petra McQueen.

The selected works are now included in the anthology. Further contributions from Patrician Press and other authors are as follows: Emma Kittle-Pey, Petra McQueen, Suzy Norman, Robert Ronsson, Sara Elena Rossetti, Anna Vaught, Kenneth Steven and more. Some of the latter works are much more loosely connected to the original themes.

The collection is edited by Anna Johnson who has also written the introduction.

Buy paperback from Patrician Press

Buy print edition from Amazon.co.uk

Buy print edition from Waterstones