Anna Vaught's Blog, page 21

January 8, 2016

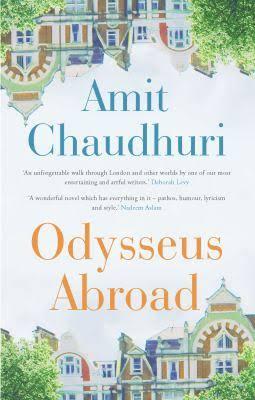

My book of 2015: Amit Chaudhuri’s Odysseus Abroad

Amit Chaudhuri’s Odysseus Abroad was my book of 2015. A fine, funny and subtle book, in a form in which, I think, he is a master. I will write more very soon, but for now here is a review by Neel Mukherjee in The Guardian which I had particularly liked.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/07/odysseus-abroad-amit-chaudhuri-review-audaciously-redraws-modernist-map

January 2, 2016

Friendship. Article for ‘At Home’ magazine.

This is by the journalist, author and broadcaster, Wersha Bharadwa. She has been a wonderful source of encouragement to me and this section of her article on friendship – authors reflecting thereon – is reproduced here with her kind permission. Wersha: thank you. xxxx

December 29, 2015

Here’s the cover of Killing Hapless Ally

So here’s the cover, with some nice words, at back, from Martha Roberts (author and journalist) and Alex Campbell (YA author of Land and Cloud 9). At the moment, media interest is building momentum prior to the launch. Fingers crossed for pitches up and coming…

While it’s a work of fiction, the experiences Killing Hapless Ally describes are very much based upon my own – the extraordinary measures a child went to to stay afloat, and how she maintained them in her adulthood: varied gallery of imaginary friends, alter ego (who turned nasty) and all. So while I hope the book entertains and makes you laugh, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t hope readers might reflect on what mental health is, what we think mental illness is (clue: there are many different types of it), how problems can develop very early in a child who learns to compensate quite flamboyantly, but who feels under a great deal of stress, and possibly how – even within someone who is otherwise healthy – there may be a great lability of mood; a rather too quick shift from normalcy to near despair and back again. I loathe, however, any text that insists you dissociate yourself from negative thought, because feelings of melancholy, sadness and even despair may be benchmarks of an emotionally healthy person able to run the gamut of all human feeling.To run away from those things is to live fearfully. I already know that some people may be horrified at my literary evocation of self harming, suicide, therapy, funerals and maleficent dead relatives, but these things I stared in the face – and my protagonist stared in the face – and found that feet were still on the ground and eyes were to the stars.

It’s interesting. As I was bemoaning on twitter earlier, a couple of folk have said, for all the best reasons, that they’ll be glad to buy the book – it’s important to support ‘people like you’. By which they mean, I think, that as kind and civilised members of our society we have to support those members referred to – in a tongue in cheek way in my book – as ‘those who can’t’. But there is another narrative tumbling along in the book, you see: it comes first from the mouth of Helen, Alison’s (the protagonist’s) godmother who is dying in a house on Cyclamen Terrace on Tyneside, to the tune of Countdown jacked up to full volume downstairs and stifling plug-in air fresheners. (Actually, this was a formative experience for me, I must admit – for Helen is based on my own godmother and the situation not dissimilar). But as I was saying, Helen looks at little Alison with fire in her eye and she says, ‘You will be the girl who did.’ She understood and she was right. People go through tremendous difficulty, but that does not mean they don’t have an intellectual life, raise a family, run a business, maintain friendships or hold down a job. I want to say that – albeit by the skin of my teeth sometimes – I have managed to do these things, never more so than when I finally accessed the care and support that, for me, was life changing and enabled me to effect permanent change. Having difficulty or illness does not make a person lesser or someone for whom we should give the sort of sympathy that also manages to demean them and suggest that they are not autonomous.

Hey look: I’ve had about thirty five years of mental health problems, but I’ve written three books, taught many hundreds of secondary age pupils, am raising three boys, feed three cats, rescued many chickens, been to two universities, travelled the world, married a bloke who stopped me on the street and asked for directions. Yeah, I know. People with MH problems do those things too. I’ve been off and on meds, received hospital support and spent a lot of time with my GP and MHRS: sometimes I broke. Then I couldn’t do any of the things I describe. I stared into a hole in the middle distance and everything was through a glass darkly and hope was a broken, jagged thing.

So how about this: say that the person who, after many years of anxiety, depression, breakdowns, self harming and OCD, kept rebounding and, eventually and moreorless, got better, well that would be some marathon, wouldn’t it? Say that the person didn’t, but kept battling. Is that not impressive? It isn’t the work of a weakling – as some may see it. It isn’t the work of a sub-species; a sort of collusion of ‘people like yous’. It’s the determination of an individual to survive and thrive. And my battle has been but a skirmish compared with what others have to combat.

But back to the book. Read it for a laugh, for company, to be startled; root for Alison; be horrified at The Hill and what happens to Muffled Mfanwy; wince at siblings like Jaggers in his vile horsehair-stuffed chair and never look at a pickled egg again! And if the book does just one tiny thing to diminish stigma around mental health problems, I’ll be so happy. And maybe no-one will come up to me and say they are glad to support ‘people like you’ – because I am you, and you are me and I am glad we met.

December 15, 2015

UPDATES ON KILLING HAPLESS ALLY

A few updates. My interview on friendship with the excellent journalist and broadcaster Wersha Bharadwa is out now in this month’s ‘At Home’magazine (and published with Wersha’s kind consent on http://www.patrician.com), my ‘Wordy Wednesday’ interview is here…

Wordy Wednesday with Anna Vaughttattooedmummy.co.uk/2015/12/wordy-…@BookwormVaught

…I was interviewed by ‘Bella’ magazine yesterday and it’s all go. The fine YA author, Alex Campbell (Land – currently nominated for the Carnegie Medal – and Cloud Nine), has also written something for the back of my book..

“Anna Vaught writes prose that is both tender and volatile to get to the heart of a difficult subject. Beautifully crafted, insightful and affirming (but most of all, laugh-out-loud funny), Alison’s journey to find mental well-being will speak to many out there who have faced anxiety and depression. A must-read that will provoke thought, debate, as well as tears of laughter.”

Have a look at www…

View original post 7 more words

A New Writing Competition

The Patrician Press Short Story and Poetry Prize

We are pleased to announce that the first ever Patrician Press Prize is now open for submissions

Age 18 upwards

Closes 31 March 2016

Results 30 June 2016

Maximum length Short stories and poems can be any length up to 2,500 words.

Judges Anna Johnson, editor; Emma Kittle-Pey, writer; Petra McQueen, writer and lecturer in Creative Writing at University of Essex; Joceline Bury, journalist.

Prizes

First – One week stay at writer’s retreat in Italy* and publication of story or poem in Patrician Press Anthology

Second – Full set of Patrician Press titles and publication of story or poem in Patrician Press Anthology

Third – Patrician Press title of your choice and publication of story or poem in Patrician Press Anthology

The winning entries will be chosen from a shortlist of six stories and poems. All six entries will be published in the anthology.

The competition is free

How to Enter On-line

http://www.patricianpress.com/submissions/

Please follow the instructions. Under ‘genre’ insert ‘SHORT STORY/POEM PRIZE’.

MAKE SURE YOUR NAME AND CONTACT DETAILS ARE NOT ON THE STORY or POEM. (Judging is done anonymously.) Your story or poem and name are linked automatically when you enter.

Stories will not be returned.

Rules for Short Story and Poetry Prize

Entry is online only via Patrician Press Submissions page.

Only one entry per person.

The competition is open to writers of any nationality writing in English.

The theme is based on ‘Refugees and Peace-Seekers’.

“No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.” Warsan Shire, Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth

“When the power of love overcomes the love of power the world will know peace.” Jimi Hendrix

(Stories and poems can be light-hearted in approach, reflecting the subjects of refugees or peace, or both.)

The winning stories or poems must not have been published previously.

Patrician Press will hold electronic and paperback publishing rights for a period of three months after which the electronic and paperback publishing rights revert to the author.

Notification of receipt of entry will be by email.

The judges’ verdict is final. No correspondence will be entered into.

Stories or poems cannot be altered or substituted once they have been entered.

Judging is anonymous. Name and contact details must not appear on the stories or poems, but inserted into the boxes on submissions form.

Entry is taken as acceptance of these rules.

* Airfare to writer’s retreat is not included. Pick-up from airport and travel inside Italy is included.

——————————————————————————

Patricia Borlenghi who runs Patrician Press is severely hearing impaired and tries to encourage writers with disabilities as much as possible.

December 9, 2015

UPDATES ON KILLING HAPLESS ALLY

A few updates. My interview on friendship with the excellent journalist and broadcaster Wersha Bharadwa is out now in this month’s ‘At Home’magazine (and published with Wersha’s kind consent on http://www.patrician.com), my ‘Wordy Wednesday’ interview is here…

Wordy Wednesday with Anna Vaughttattooedmummy.co.uk/2015/12/wordy-…@BookwormVaught

…I was interviewed by ‘Bella’ magazine yesterday and it’s all go. The fine YA author, Alex Campbell (Land – currently nominated for the Carnegie Medal – and Cloud Nine), has also written something for the back of my book..

“Anna Vaught writes prose that is both tender and volatile to get to the heart of a difficult subject. Beautifully crafted, insightful and affirming (but most of all, laugh-out-loud funny), Alison’s journey to find mental well-being will speak to many out there who have faced anxiety and depression. A must-read that will provoke thought, debate, as well as tears of laughter.”

Have a look at www. patrician.com for a new writing competition, too!

December 2, 2015

Alas, no – I cannot offer you Albert, but look within the...

Alas, no – I cannot offer you Albert, but look within the book and you will find him: a vital presence – and with a motley crew alongside him.

Killing Hapless Ally will be with you on March the third! This novel will be published with Patrician Press and you can order it through any bookshop or buy online at Amazon, GB Books, Waterstones and so on. I will be talking about the book and doing signed copies at its launch at Mr B’s Bookshop on March the third. Meanwhile, I have been in ‘At Home’ magazine talking about friendship and its ebbs and flows(viz a viz Killing Hapless Ally), I am looking forward to my first poetry publication with The Emma Press next year, I am completing a pamphlet and working on The Next One.

As you see below, the award-winning mental health journalist, Martha Roberts, has written in praise of Killing Hapless Ally and I hope that when the book comes out, readers will enjoy its rattling tale as well as find comfort in its pages. It is a work of fiction, but, as I write in the foreword, very much based on experiences in my own life. There is still so much stigma surrounding mental health and mental illness – neither of the terms is ideal – but I have tried to tackle it head on in the book as I saw it and as I experienced it.

So here’s the back cover of the book.

Killing Hapless Ally is a tale of an individual grappling for sanity and identity; a black comedy in which we discover how Alison, its curious protagonist, conceived in childhood an alter ego called ‘Hapless Ally’ in order to present a different, more palatable version of herself to her family and to the world beyond. Ominously, the alter ego began to develop autonomy. You learn how Alison had to deal with that: she had a lot of help from a varied catalogue of imaginary friends! The book is about serious matters: fear, confusion, dark days of depression and breakdowns. It carries with it a timely message to anyone poleaxed by depression and associated problems – or any reader interested in the windings of such things. You can, like Alison, survive and prevail. Ah, but how would you do it? If you had to – to survive – would you kill for it? Now that is an interesting question.

‘Anna’s story of Killing Hapless Ally is a heart-rending book that covers the subject of depression in a brilliantly funny way – no mean feat. With every chapter I found myself willing Alison to thrive and prosper as the feisty and incisive survivor that she is. Go, Alison!’

Martha Roberts, author, columnist for Psychologies magazine and award-winning mental health journalist.

Cover illustration: © Charlie JohnsonkillinghaplessallycoverISBN 978-0-9932388-4-0]

October 29, 2015

A quick, creepy write for Halloween.

A light drizzle settled in and, as Berenson walked home from an unremarkable job in the city, the darkness began to fall over London in November.

From office to tube and from tube to the beginning of his walk home, he was content enough. Even with the grey evening, the drizzle was refreshing on the skin after a day in the office. He observed familiar faces on his way, nods of acknowledgement and, to a certain extent, he fancied, of understanding. The day had gone tolerably well.

Walking up the final small spiral staircase from the tube station, though, Berenson was struck with an odd feeling: of the familiar being just a little off beam. He couldn’t put a finger on it, but it made him shudder. Thinking carefully, the white tiles looked perhaps a little yellowing; the steps altogether dustier. Now and then, he felt someone brush against his shoulder, but yet he had no sense of someone quite so close to him as he made the final ascent to the street. Again, he shuddered.

Walking in the direction of home, he stepped first into the everyday sight of a London street, with its selection of shops. He bought an evening newspaper, rolled it up and put it under his arm. Again, the shops looked a little different. There was an unseemly and garish quality to the lighting and the bright displays of goods, even in the small newsagents where he stopped every evening. He had never noticed that before, always enjoying the convivial warmth of the shops and shopkeepers as he walked home. He reached the end of the road, where shops began to give way to the residential streets. Berenson had an odd feeling – almost like the warmth of someone’s breath on his back. He shook it off. “Maybe,” he thought “I have one of my heads coming on. I’ve been working pretty hard ” But the feeling did not abate: it grew stronger and more disconcerting, accompanied with an inchoate understanding of something slinking his way.

Rounding the corner into his own street, it occurred to Berenson that he had yet to turn round. To have done so would have been to give credence to what he thought a foolish sensation. So he walked on. But, as he did so, he was conscious of the increasing closeness of another individual and, also, of footsteps behind him. Yet, when he stopped, so did the sensation and the hoof taps. It was true: they did sound very like a shod horse striking a road. Moving on again, walking more quickly, the steps and the individual kept pace with him. Looking around, he had the bizarre sensation that he was seeing everything as it always was – but through a glass darkly. And that, if he were to call out, no sound would issue forth.

Walk on, walk on. Did he hear a laugh behind him? Was the breathing full and throaty? And did the man behind him identify himself as Berenson when, unable to bear it any more, Berenson looked back?

Daylight saw Berenson travelling, as usual, down a pleasant city street and past shops doing brisk trade and on the London underground. All was well. But tonight a story would appear in his newspaper about the diligent, well respected man, found cold and dead in his street last night. And the man who cut him down would, while there was time, sit in Berenson’s favourite chair and tweak at what we know of our everyday familiar world. He would shuffle off his steel-tapped shoes, brush a little lint from his fine dark suit. And he would laugh. And soon he might come for you.

October 9, 2015

Some more publication plus MacNeice and Kavanagh

I am very excited to say that my work is being included in a poetry anthology published by the Emma Press. Here they are

I wrote a series of poems called Pembrokeshire Poems and they picked one called ‘Cast out my broken comrades’, the title of which draws on Homer and also a poem (which itself does the same) by Louis MacNeice called ‘Thalassa.’ I am so pleased as I didn’t expect to achieve publication so soon.

I’d been re-reading Louis MacNeice prior to starting these Sea poems; he is a great favourite of mine and he always has been. MacNeice appears briefly in my first novel Killing Hapless Ally (Patrician, February 2016) and there is a refrain from his poem ‘Meeting Point’ in the novel, too. If you read the book, you’ll see WHY and HOW ‘time is away’ and also (I quote from Patrick Kavanagh’s poem, ‘Prelude’ – another refrain) why ‘the millstone has become a star’ – the epigraph to the novel, a refrain and there at close of day. (I was granted permission from literary estates for these at no charge – very generous.)

For me, the lines already in my head and the lines I have yet to read, will always be salve and solution.

The poem itself decribes a dawn voyage across Ramsey Sound to the island; the voyage itself is both literal and figurative – as I expect you guessed. It is about being broken, being lost and experiencing the first moments of healing. A ‘sea-change’ you might say, quoting Ariel in Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest’.

Do have a look at The Emma Press. They are a dynamic lot – much going on – and their Anthology of Motherhood contains some stunning writing. You can buy it through the site – or borrow my copy!

By the way, I have written (I’m aware this sounds reckless) a chapter book to enter for The Bath Children’s Novel Award (I hadn’t even told my husband I did it), but I’m still deliberating whether it’s too rough and ready to submit.

But back to the poem. The Emma Press Anthology of the Sea will be published in October, 2016.

The picture of Ramsey Sound, above, is from the Pembrokeshire South East Energy Group website.

October 8, 2015

An extract – featuring Albert Camus – from Killing Hapless Ally. This Chapter is called The Mis-education of Alison.

Pre-order from 3rd of February, folks! The ISBN is 978-0-9932388-6-4 and it’s published by the wonderful independent press, Patrician. Killing Hapless Ally is not a book for everyone. It’s densely packed with idea and allusion; it’s dark and (I hope!) comic. But if you like it, take it to your heart and that will make me so happy. It is fiction, but within it, there lies a distillation of what I know, what I have found out and what I have been through. It is about how mental illness takes hold – how it can settle in so young – and about imaginative ways to fight it. And that, lovely readers, is all me. x

NB: there may still be some editorial changes to this copy before I bid it goodbye in a few weeks.

THE FOLLOWING EXTRACT CONTAINS EXPLETIVES. Actually, there’s a hefty amount of creative swearing at various places in this book.

Not for this homme a lie down in the afternoon, but a manly growl after lunch, some Gitanes and a marc. Step forward Albert Camus and also the story of becoming an existentialist on a campsite. Not Albert; oh no, no, no: he was far too cool to be seen in a Fucking Caravan. It was Alison, trying to translate the world into something that made sense.

We have already shared fateful tales of The Fucking Caravan, of the entrapment between two alder trees and, on the same trip, tales of two blacksmiths. However, on that same ‘holiday’, parked up by the Seine and sitting under the willows for days (with her parents somewhere else; they didn’t say) Alison began a roaring and extraordinary affair with Camus. It was a reading summer, between the two sixth form years. All around was the sense that people were dropping like flies and the deaths of Dad and Santa Maria must surely be imminent; she just hoped, ever practical, they didn’t happen when the two were out in the car, or maybe driving on to the cross-channel ferry, with everyone hooting furiously behind them. But the reading: for days on end by the river: Sartre’s Nausea, Genet’s The Thief, and, best of all, Camus’s The Plague, The Fall, The Outsider and Selected Essays and Notebooks. Also, at speed on the journey home, Simone de Beauvoir’s The Force of Circumstance and, cheerily, A Very Easy Death. When she got home, Alison devoured Gide’s Straight is the Gate and Fruits of the Earth: ‘Nathaniel—I will teach you fervour!’ Fervour: Holy Fuck—what was fervour? What was lust for life? Were those things somewhere in the unknowable distance, just visible beyond the bacon grease of The Fucking Caravan? She was intoxicated: dislocated entirely from her surroundings. The dislocation did not provide a new or unfamiliar sensation, but this kind of dislocation was one in which she was on fire and in splendid company.

‘Come. Come away with me now. Tonight!’ said Albert Camus.

Now, one could dwell on the literary qualities of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, but the most impressive thing for an adolescent Alison (she whose constant companions to date had been imaginary Swedes in a crawl space) was the sense she gained of Sartre and de Beauvoir’s love affair; that they wrote and argued and shared and, of course, smoked (like Helen) in the cool way. And when de Beauvoir wrote about her love affair with Nelson Algren—not to mention sharing bricks (bricks: Ooh la la!) of raspberry ice cream with him—Alison had a peculiar light headed and heavy hearted sensation. It was, we would have to say, the first knowledge of the erotic. And it hurt, because it didn’t exist in any part of the real world, where there was just getting off and, for some girls, an early, clumsy, grasping fuck. When Simone de Beauvoir wrote of their ‘contingent lovers’; of love affairs, known about by both but clearly allowable and part of happen-stance rather than a dedication for a lifetime, it sounded both painful and delicious. How entirely entrancing for the teenage Alison that de Beauvoir and Sartre wrote and expressed an intensely creative life to one another. This was something Alison could never quite get out of her head. And when she tried and failed to engage something which might look like it, the stone dropped in her heart and she was scared to open her hand in case the frightening thought was there, pressed into the palm, waiting to open. And she was scared of being herself: Just Alison (as Denis the Lusty Blacksmith had it), while in her heart remained the appalling leaden feeling and the acute sense of being separate; weird, possibly a killer; not inclined to the magazines and spontaneity of her female peers: missing the point always. Wrong and Weird Kid. She willed herself to live on in a way that was meaningful and hoped that she would find people to discuss these feelings with; that she could know someone who understood about absurdity, existence precedes essence or the frightening experience Sartre’s Roquentin has when, in Nausea, he touches a door handle and comes face to face with jarring, sickening anguish: that anguish lived alongside Alison permanently. At five, it had started somewhere after Saturday morning cartoons, as the day unfurled; at sixteen it began after Weetabix and before the first application of lip-gloss.

‘This I understand: it is when the scenery collapses,’ said Camus.

He made it sound exciting in his low tone. But it wasn’t in real terms: at least, not yet; instead, it was terrifying and yet Alison had a timorous sense that from that terror came only a beginning. That definitely made sense. Good god: intellectual heat; the erotic in its most subtle form; a notion of how to live with hope, when God quite clearly does not exist and we must travel to the frontiers of our anxiety to understand where to start. Alison was not asking much in a man, then.

Ah—but one ready day along came Albert, ready for action. If you have ever read his peculiar, flat, sparkling, cold story of Patrice in The Outsider, then there is little to express. But if not, imagine a wandering, solitary individual, not inclined or feeling the pressure to act as expected. Not cruel, but mercenary because appetitive; plainly erotic in responding to his needs as and when they push forward, articulate of who and what he is and yet without what would feel like morality to us. He did not cry when his mother died; he shot a man on the beach and did not express regret, only annoyance. For the teenage girl, it hit a nerve. The description Camus had of his protagonist as a solitary and wandering individual; as somebody entirely alone and on the edges of society, now, that was the truest description of her to date. It was—and there is no other way to say this—a first orgasm. Not only with the plainness of the character and Camus’s prose, which Alison gamely attempted in both French and English, but also because of the man. Let us describe him. Alison had to get over Mersault first, a man both in love with the world and separate from it. Camus told her of how his protagonist was inspired by a stubborn passion, for the absolute and for truth. His truth remained negative truth, but it had its own beauty and without it there could be no adroit comprehension of ourselves and of the world; no self containment. Mersault’s life was that of a foreigner—a stranger—to the society in which he lived, and he wandered about on the fringe, in the shadows of others’ lives: plain, but deeply sensual. Such descriptions made Mersault enormously attractive to Alison and made her fall more for the man who wrote him into being. Such a telling of the outsider, the wandering foreigner living and breathing a negative truth, pierced and had a difficult heat for her because, of course, that was Alison. We could say she was Weird Kid—plenty did and probably still do—but l’étrangère would sound altogether more arousing, non?

Alison had photocopied a picture of Camus: it was of him, apparently sitting on a rather lopsided sofa, and leaning forward with his hands tensed, his mouth slightly open, his eyebrows raised and his trousers showing his socks as he inclined towards a co-combatant to advance his argument. He was so fabulously French; so fabulously exotic because he came from Algeria, that he carried off the sock thing with élan; socks were not normally a detail of erotic piquancy. Camus might have been describing how brilliant it was that William Faulkner had pulled off the language of high tragedy; that a man from Mississippi could find language that was simple enough to be our own and lofty enough to be tragic. Or perhaps he was dictating something for the Resistance magazine, Combat, of which he was the editor. But, to a teenage girl, under his spell he was also evincing arguments for,‘Come away with me.’

And, ‘Let me show you.’

Or, ‘Let me show you how to live in the face of despair. Sit on my knee and we will begin.’

And, occasionally, when the Oran sun roused his temper, ‘Come here now and stand against this wall. I will take you.’

Was this what Helen had meant, gifting Alison the Camus as she lay on her Cyclamen Terrace deathbed? It was a jolly long way from a few drunken fumbles in the dark when they—the boykind—mistook her for someone else. Camus would have taken a bowie knife from his pocket and cut her out of her clothes, grazing her skin and eliciting just a little blood as he went. Later, he would lick the drop of blood off the knife like a wolf.

Albert’s cadences were delicious: he was declaiming phrases of profound, shattering erotic power to Alison’s ear. And by God he had enough style to be vulgar, if he wanted. Camus had a history of manly pursuits, too: goalie for Algiers; a fine swimmer and athlete. She had a sense of his being a consummate man. Funny; brave; a demon in the bedroom—if you ever got that far, because what are walls, floors and furniture for? And, unlike JK, he could have built a wall or changed a tyre. On the occasions when Alison went to other girls’ bedrooms, she saw they had pictures of The Cure, or Bono, when he was ragged, young and angry. She, meanwhile, had a picture of Albert Camus next to her desk. People said, ‘Who’s that?’ and she said, ‘My godfather. The notion felt entirely, naughtily fitting, for the Camus books, en Français, that Alison possessed had been bequeathed to her, as you learned earlier, by her godmother Helen, studying Camus at The Sorbonne. Perhaps Helen had been similarly intoxicated (which made the Terry the Fat Controller, the unexamined life, Friday-pie thing even more depressing). So the honorific chimed as fitting. Plus it felt like Albert leaned over Hapless Ally in a proprietary and manly style. L’Étranger was inscribed with the words “Helen Griffiths, Paris, le 19 Janviér 1962” and Alison had always hoped that, in leaving France for Terry, his mother’s pie and a new life in Tyneside, Helen was able to say, like Camus’s protagonist at the point of death, that she knew she had been happy. She hoped it was like this for Helen especially when the morphine gave her respite from pain and the unexamined life downstairs, punctuated by the sickening puffs of air freshener from the Cyclamen Terrace plug-ins.

Now, all those years it never mattered to Alison that Camus had been dead ten years before she was born: he was there on her wall now.

Godfather. Most louche, brilliant, gorgeous godfather.

She saw in his Notebooks that he wrote, ‘I loved my mother with despair. I have always loved her with despair.’ Good God. He even understood that. It was exactly how she felt about Santa Maria. And by God (although He is Dead if He ever Existed) Albert was brave: he would stand in the face of despair and say that now he was free.

Ah: the growingupsexthing. Alison had hopeless expectations, really, for while Camus smouldered away behind her closed eyes, real life was, shall we say, more a damp inconsequential thing than a smoulder. There was Johnny in the barn. Always, ‘Let’s go to the barn,’ a bunk up against a bale: no use there expecting conversations about Proust. She asked him about books and he said, ‘Why would anyone want to read boring books?’ But in school, there was an important dalliance with D.H. Lawrence. It was Sons and Lovers and she remembered mostly Paul Morel’s loving: not the bit which was like a communion (with Miriam) but the bit which was ‘too near a path’ with rather racier Clara. The evocation of Paul’s mother, however, as he drifts back to her—and drifts to his own future death (as Lawrence himself had it in his notes on the text), now that was a theme best avoided during these delicate years. Besides which, no-one would have got it because at that time boys just wanted to get you drunk and feel you up in a dark room when the parents are away. Only in reality, they were feeling up someone else. Like Heroic Alice. Oh yeah: Heroic was still around; jiggly tits, cool-thriving and diving and looking on her hapless (again, ironic, though note lower case) counterpart with scorn. She had the best clothes and hair; told the kind of jokes boys liked. When she moved upstairs, the party moved with her, while Alison stood downstairs thinking about existentialism and, ‘I’m a misfit and nobody fancies me.’ Alison was definitely Weird Kid. Good job she had Albert