Anna Vaught's Blog, page 12

May 20, 2018

Updating, writing, news and a scholarship

Follow me on twitter https://twitter.com/BookwormVaught

Hello all.

I am just in the process of updating this site so that the rolling twitter feed is engaged and I will also be producing a newsletter. I’m gathering steam – so it’s about time.

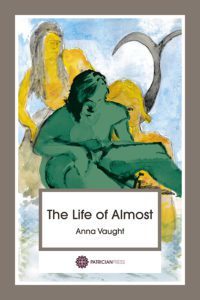

I have just finished edits on my second book, novella, The Life of Almost. This will be out on August 31st with some events local to me. If you’d like to invite me further afield to do or share in an event, go ahead. That would be lovely. Also, if you would like to review the book, great.

You can order the book here, from the press website or buy through a lovely indie bookshop. If they don’t stock, they can order. It is available online at both Amazon and Waterstones, but the latter is still not stocking texts by this lovely little boutique press for – I asked a manager – ‘purely commercial reasons’. Well.

http://patricianpress.com/book/the-life-of-almost/ That’s boy Almost on the cover; he’s reading on the sand with a brace of mermaids…

Published August 31st, 2018

Published August 31st, 2018

This is a dark comedy set in Wales and a spectral reworking of Dickens’s Great Expectations. Almost is a boy, brought up by his sister, Perfection. He is shrouded by bereavement and surrounded by the hauntings of his family’s undead. He plays in the sea caves, visits graves, amongst mermaids, longing mermen, morticians, houses that respire and a poltergeist moss that grabs your foot. A cast of family and friends drawn from sea caves, the embalming table, the graveyard and the dark Clandestine House, which respires heavily and in which time has stopped. And like Pip, he sings into the sea and likes to tell stories – the key theme of the book which is the story of his life, his struggles and triumphs. He is thwarted in love but understands – the night he meets a ragged convict, for the convict is a merman, come on land – that he has deep and commanding powers.

A substantial extract from the first chapter of the book is published on the 25th of May in New Welsh Reader. You can navigate to information on that from here:

https://www.newwelshreview.com/

Next month, two of my (short) short stories are published in volume two of The Shadow Booth, a great place to read weird and eeried fiction. Boom.

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/the-shadow-booth-vol-2-books-horror#/

I have applied for a Gladstone’s Writer if Residence slot for next year because, reader, day job, three kids, assorted other folk to look after, books three and four to edit and A RESIDENTIAL LIBRARY OOOOOH. Fingers crossed for me?

I mean look at this place? https://gladstoneslibrary.org/events/writers-in-residence I am determined to book a stay there if I don’t manage a writer in residence slot – it is, I know, very competitive.

Also, my husband and I are sponsored a weekend ticket for The Literary Consultancy’s Get a Job in Publishing weekend course

https://literaryconsultancy.co.uk/2018/03/get-job-publishing-sponsors-showcase/

and I just did the same for the Bare Lit Festival and it has gone to a wonderful home: you know who you are! Have a wonderful time xxx

Sponsoring the ticket for TLC led me to write this blog post for them; it’s about writing a book when you have no time and managing self doubt as you do it. Here:

https://literaryconsultancy.co.uk/2018/04/managing-self-doubt-write-book-dont-time/

It begins…

I am in my early days of my writing, so you are not looking at someone who is a seasoned professional.

I’ll tell you what I am.

I am a quick learner; I chat and make contact very quickly. I am acquisitive of information, always reading, thinking and noticing. In a way, I am always working. What I thought was not possible has turned out to be something rather different. Not easy exactly, but more accessible than I had managed. And I seem to have written a good deal.

In late summer 2014 I sat at the kitchen table and started typing a question. That question became the first line of an autobiographical novel. That first book was published in March 2016. I realise now that twenty months from first line to publication is a bit of a clip, but didn’t know it then because I was so naive. I do think, for what it’s worth, that naivety is underrated. My second book comes out this summer (2018), the third is placed for 2020, and the fourth is going straight to an agent and I want you to cross everything here. I am also pitching something non-fiction collaboratively with a much finer writer than I (if she reads this; don’t argue) and working on pre-publicity for the second book. At last count I have also published two poems, a very short memoir, reviews, features, guest blogs, short stories, and creative non-fiction. Flash fiction is on its way. I think in all I’ve published twenty or so pieces across journals and magazines, web and print. I’m quietly increasing my stock; my ‘profile’. No-one told me to do this. Again, it’s that naivety. I just thought, ‘Give it a go,’ rocked up and started pitching. And it worked. I also found time in that period for some rejections, lost manuscripts, and serious faffing about when second and third books were written to time for someone who then rejected them with a form letter and didn’t invite me to send further work. That set me back – time-wise, mood-wise – but I’m tougher now. And I realise the passion I felt for one of my rejected projects obscured the paucity of its quality. Or marketability. The fact I had no adequate platform. Cave scriptor.

now that twenty months from first line to publication is a bit of a clip, but didn’t know it then because I was so naive. I do think, for what it’s worth, that naivety is underrated. My second book comes out this summer (2018), the third is placed for 2020, and the fourth is going straight to an agent and I want you to cross everything here. I am also pitching something non-fiction collaboratively with a much finer writer than I (if she reads this; don’t argue) and working on pre-publicity for the second book. At last count I have also published two poems, a very short memoir, reviews, features, guest blogs, short stories, and creative non-fiction. Flash fiction is on its way. I think in all I’ve published twenty or so pieces across journals and magazines, web and print. I’m quietly increasing my stock; my ‘profile’. No-one told me to do this. Again, it’s that naivety. I just thought, ‘Give it a go,’ rocked up and started pitching. And it worked. I also found time in that period for some rejections, lost manuscripts, and serious faffing about when second and third books were written to time for someone who then rejected them with a form letter and didn’t invite me to send further work. That set me back – time-wise, mood-wise – but I’m tougher now. And I realise the passion I felt for one of my rejected projects obscured the paucity of its quality. Or marketability. The fact I had no adequate platform. Cave scriptor.

None of this is my day job.

Now, you may have seen elsewhere on this blog that I have a bursary called The Fabian Bursary. Do you think you might to like to apply for it for this September. Read this, but just something to note: I have removed all age restrictions. My background is largely secondary teaching, but I do see that as I move along with my writing, I could be supporting a broader demographic. Also, it needles me that there are age limits on things, such as literary prizes and funds. Because so many people come to writing – or study – later. Because of lack of confidence, physical and mental health problems, caring responsibilities, prejudice or poverty. So this is a gift. It’s hopefully the gift that no-one gave to me when I was younger. You could use it for a GCSE, an A level or any creative writing project, say! xxx

https://annavaughtwrites.com/the-fabian-bursary-announcing/

Right: what else have I done. Creepy memoir – NOTE MEMOIR: ARE YOU GLAD THIS AIN’T YOU RA HA??? ‘The Shadow Babies’

http://www.theshadowbooth.com/2018/01/memoir-shadow-babies.html

Also, the few reviews I’ve done in the past few months:

http://review31.co.uk/essay/view/50/diversity-risk-taking-and-community-a-celebration-of-2017%E2s-small-press-anthologies This is about small press anthologies.

http://review31.co.uk/article/view/542/laughter-in-the-dark This is about Takeaway, by Tommy Hazard at Morbid Books.

https://thecontemporarysmallpress.com/2018/02/16/he-built-a-house-and-next-to-it-a-church/ This is my review of As a God Might Be, by Neil Griffiths. This was my book of 2017.

And here my review of the late Naseem Khan’s memoir, Everywhere is Somewhere. https://thecontemporarysmallpress.com...

And did some co-editing on this https://thecontemporarysmallpress.com... Currently waiting for commissions for the next anthology from this press, Tempest, which I’ll help to edit and for which I will write a foreword. You’ll be able to follow it here: https://patricianpress.com/books/ And aren’t they pretty books? Such strong artwork.

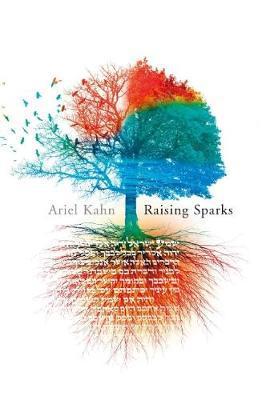

And finally, I have a July deadline for my fourth book, The Revelations of Celia Masters (news on which will follow, when I can) and my third book, Saving Lucia – which is about the last days of the Honourable Violet Gibson who shot Mussolini in 1928 – oh and her co-patient in Northampton Infirmary, Lucia Joyce, daughter of James Joyce. Bluemoose is a wonderful press and it’s so lovely to see it in the sun for works by Ben Myers and Harriet Paige, and the work the press is doing as part of the Northern Fiction alliance. Here: https://bluemoosebooks.com/ and go and buy the book below now?

Anyway, head down now with finishing fourth book and teaching (and my own eldest is doing GCSE at the moment so it’s all go) BUT I am having a little two day holiday in London, when I get to go to the launch of this little beauty:  There’s a launch at Waterstones Islington on June 21st and it’s pubished by Bluemoose. I was lucky enough to read a proof copy ahead of time and thoroughly recommend it to you. Here: this is a synopsis from the website of Foyles:

There’s a launch at Waterstones Islington on June 21st and it’s pubished by Bluemoose. I was lucky enough to read a proof copy ahead of time and thoroughly recommend it to you. Here: this is a synopsis from the website of Foyles:

Malka grows up in the Old City of Jerusalem in the confines of the Ultra-orthodox Jewish community. Meandering through the narrow streets she finds herself at the door of one of the city’s most renowned and reclusive mystics and discovers her father’s top rabbinical student, Russian immigrant Moshe studying forbidden Kabbalistic texts. She has a disturbing vision of a tree of prayers growing up inside the house, and the prayers all seem to be talking to her. The prayers become a giant bird, and chase her from the house. Malka has unwittingly uncovered a great mystical gift. Kabbalists believe that since the world was spoken into existence, if they can hear and understand that original Divine language, they can use it themselves, to shape and manipulate reality. Once in a millennia, a kabbalist is born with this ability. It turns out that Malka is one of them. After a disastrous first date with Moshe, Malka flees Jerusalem for Safed where she is drawn into a cult called Mystical Encounters, run by charismatic cult leader Avner Marcus. Avner is unsettled by Malka’s authenticity, and she is not allowed to attend classes. Her only friends are former night club singer Shira, and traumatised ex-soldier Evven. Malka sets up her own mystical retreat in the woods, at an abandoned construction site. When she reveals this to Avner, he forces her to take him there and tries to rape her. Malka manages to evade him, and then burns down the cult after manipulating the Modern Hebrew word for Electricity, Chashmal

Malka heads for Tel Avi, and sleeps rough on the beaches of the mixed Arab-Jewish city of Jaffa. Here she is discovered by legendary Arab chef Rukh Baraka, who is seeking to rekindle his career by training Arab and Israeli street children to create extraordinary food for his new restaurant, the Leviathan. Malka bonds with fellow runaway Mahmoud, who is escaping the wrath of his Imam father at his “deviant” sexuality. Mahmoud reveals the city behind the city, the hidden Palestinian history of which Malka has been ignorant. Moshe has been trying to find Malka and is forced to confront some of his own demons, including the disappearance of his younger sister when she was in his care. Moshe swears that he will not lose another girl he loves.]

And that’s it for now!

Anna xx

April 23, 2018

February 22, 2018

On mentoring…

ON MENTORING

IT IS POSSIBLE YOU MAY NEED A HANKIE. I am writing quite specifically about one of my three boys; he’s thirteen.

I want to tell you about something which happened a couple of days ago to my middle boy. He likes to make things. Anyway, he’s started making an infinity table in his Man Shed. Here, above, is a photo of what an infinity table is; cool, innit? This is not his, but similar to the one he’s making, with colour change and fade from LED lights.

Anyway, I took him to see the very jolly men who run a glass cutting and fitting shop in a nearby town and they were awesome. I’d already talked to the lad about how there was brilliance and skill everywhere; links to make; you know how I go on about communities, too. Anyway. They talked and joked with him; did not talk down to him; chatted over the project; rang a friend up and got him to price the coloured film lad will need as glass overlay so the table has depth. They were warm and kind and funny.

They mostly ignored me, save for the occasional knowing wink. Spot on.

Then they cut the glass (which he enjoyed seeing) and lad told them this was not a school project; he just liked making things. And didn’t like school. They asked him to bring the finished item back to show them and, if he wanted, to stick business cards (‘Easy to make, lad’) up there in the shop – or maybe photos and they can say, ‘Yes we know someone who makes those.’ They then suggested a making price and selling price and reassured lad that this was business, pure and simple. ‘This is what you do, son. That’s how it all starts.’ I could tell he was listening, rapt, because it’s all very well mum rabbiting on about things, but our young don’t need to hear it from their primary carers (though that helps); they need to see things in action and have conversations with others in their communities. And sometimes their aspirations are killed off. It’s true. We have to so careful.

Lad hesitated about the notion of taking in a table to show them. They saw, ‘No, only if you want to, but you keep in touch and tell us how you get on.’

‘But my first table might not be any good’ says lad.

‘Of course it won’t be, son. That’s BECAUSE it’s your first one.’

They wouldn’t charge for the glass either. So I’m taking them cake and treats and a card, BECAUSE my boy LIT UP. He totally LIT UP. Because of the encouragement and because it was cool and kind of exciting. This is mentoring and it is priceless. It’s also everywhere and I do believe that. And it need not be extended, but perhaps a few meaningful encounters in which someone feels valued and that there are possibilities which they can extend with just a bit of guidance.

Now, lad is dyslexic. Yeah, lots of people are. But it makes school that bit harder; boring and tiring. What is more, I have listened to several conversations – and I will leave the provenance unstated but should emphasise that I am not only focused on what is said in school but also in families – about how those are bright must go to university. This is what ‘doing well’ means. My hackles go up with that. As they do when my lad has been lectured about he can overcome his dyslexia and ‘go to a good university.’ I winced, too, when his older brother, my eldest boy, was recently told that there were only two jobs he’d be able to do with his A level choices. Yeah, right: like the world is not plural and various and with all kinds of jobs that exist even if you lack the vision or knowledge to imagine them. Yes, it’s tough, but get out there, talk to people. I will write more on this theme another day! I absolutely believe that going to university is not the only mark of brilliance; going to university may not a clever businessman make. Going to university does not necessarily endow you with the kindness and compassion that might transform the lives of others. I went to two – yeah, Oxbridge and Russel Group – but I don’t figure that this gives me intellectual dominion over someone else or that I am cleverer than they are: lots of thick people go to Oxford and Cambridge. AND OVER MY DEAD BODY will I hear a young person measure their worth against whether they go to university or not or be told (as I heard lad getting told) that ‘he will find his own place’ before another young person was turned to and praised for their cleverness.

What a narrow way to think or to imagine intelligence.

Then, what intelligence to lead my child forward with clear sight and kindness; with compassion.

So anyway, I was thinking that if your offspring is bored or demoralised by school, look within it – and to support staff as well as teaching staff – and look beyond it in your communities for mentoring, for people who inspire and listen to your child and who are not limited in their view of the world; who do not give advice which depresses the child or young person based on that.

We had THE BEST example of mentoring that afternoon. Mentoring is about kindness, about listening and also about being flexible – and smart – in your view of the world and in how you regard the views, aspirations and ideas of children and young people. And (my background is in teaching and a portfolio of volunteer posts as well as writing) they will teach you things too.

As I said, my boy LIT UP, we got back to the car and he said, ‘Oh mum. Why are you crying?’ ‘I’m not.’ ‘So ARE.’

Here: this is the project before the infinity table. A home-made tubulum (plumbing bits and salvaged wood), played with my flip flops. Something cheery for you!

January 13, 2018

Writing updates from Anna Vaught

So first of all two updates…

A book I’ve co-edited is out this March. My Europe by Patrician Press.

http://patricianpress.com/book/my-europe-a-patrician-press-anthology/

My second book, a novella called The Life of Almost, will be published by Patrician Press this October.

http://patricianpress.com/book/the-life-of-almost/

My third book, Saving Lucia will be published by Bluemoose Books in 2010…Here are its central characters. The Honourable Violet Gibson, who tried to assassinate Mussolini in 1926, and her fellow hospital patient, Lucia Joyce, daughter of the novelist James Joyce.

Here are the other pieces I’ve had published since mid December.

http://losslit.com/feature/give-sorrow-words/ ‘Give Sorrow Words’ – narrative non-fiction

https://thecontemporarysmallpress.com/2017/11/24/an-indie-press-christmas/ a piece about buying Christmas presents from the indie presses

AND

https://thecontemporarysmallpress.com/2017/12/01/everywhere-is-somewhere/ – a review of the memoir of cultural pioneer, Naseem Khan

the contemporary small press

A site for small presses, writers, poets & readers

http://review31.co.uk/essay/view/50/diversity-risk-taking-and-community-a-celebration-of-2017%E2s-small-press-anthologies An account of my favourite mixed form indie anthologies of 2017 in Review31

And https://visualverse.org/submissions/t... one hour to write a piece stimulated by this month’s image…

Coming next, reviews of Neil Griffiths’ As a God Might Be (Dodo Ink),

Tommy Hazard’s Takeaway (Morbid Fiction)

…and Gary Budden’s Hollow Shores (Dead Ink)

None of this is my day job and yet…

Anna xxx

December 6, 2017

Five, twelve, fourteen. The day after the brexit vote

FIVE, TWELVE, FOURTEEN

June 24th 2016. The day after the Brexit vote.

Here is how it went.

I had my first texts very early and a phone call from a friend in tears. I’d thought, as she, that the vote would be close but the other way round. The previous day, we’d looked, together, at the ‘Vote Leave’ balloons strewn about in the centre of our small town and thought, ‘Ha’— but still I was restive and feeling depressed; the atmosphere did not feel good. In the week before the vote, I had felt miserable and angry that many people in my own extended family were posting union jacks on Facebook with a ‘Remain’ shout. I was furious that people, some of whom I knew pretty well, did not appear to understand where some of the funding for new building had come from in the places where they lived.

‘What have they ever done for us?’ I heard someone say in Merthyr; in Newport, ‘It isn’t fair that these immigrants come over and are immediately given a council house!’ and I began to argue but was told I was soft and it was alright for me. I am not having a pop at Wales here; it’s where my people are from and I speak of it only because this is where I was in the pre-Brexit week; I rounded off this week in an idyllic valley in the Black Mountains and heard talk of how it was too crowded shortly before I walked a mile and half up the valley to the next house to deliver a get well card. On the way I saw only a dead badger. And then in a local town, I heard the word ‘darkie’. It is not that these sentiments are not thought or exchanged, just that it made me tremble to hear such things expressed more openly and with such vigour. When I got home I was so rattled by some of the papers’ coverage that, topping up with petrol just down the road from home, I turned the offenders round. It was not my place to be a censor, but I couldn’t help it, with all that inflammatory talk.

Yes, that Pre-Brexit week was a tough one. You remember the bus? The Bus. The Bus that Couldn’t Do Maths? I hated that bus. Where is it now and what do you suppose it says? ‘It’s what THEY WANT you to think! But seven is NOT a prime number!’

I had listened, as The Bus That Couldn’t Do Maths chugged on, to people talking about British sovereignty and purity which enraged me with its confident stupidity. ‘I hate it when you can’t hear any bloody English being spoken!’ said one. That was in Asda. WHAT IS MORE it was Asda in West Wiltshire, which is not exactly heavingly multi cultural. I was very close to doing the thing called Having a Go. I was minded to be right in there with words on celebrating the polyglot, the verbal texture, the joy, the fun, the life; to speak about how—the same person was also talking about preserving the English language—the English we speak was not suddenly born—Pop! Huzzah! It is English! It is a pretty, pure thing for local people only!—and added to with cultural reference and dialect; that it was, instead and like us, a series of graftings: Anglo Saxon words, Latin, Norman French; you know. I was about to go for it with other words: with jamborees and bungalows and pyjamas and…you get the picture. But I didn’t. I was too upset. And also, I did understand the importance of the vote for people. Because many of those people felt disenfranchised and that their voices were not heard by those in power, by a perceived ruling elite. It was only the other day that MP Jacob Rees Mogg spoke of how one problem in government was that there weren’t enough Etonians. Meanwhile, a house nearby had pages of statistics pasted on its windows: the costs of the EU. This fellow had also helpfully pasted up statistics on immigration with lists of dubious figures on their cost. Like teaching them to speak a language that everybody understood, say. We racked up loads in costs for language courses and teaching them English customs and gifting them five bed council houses because Johnny Foreigner has loads of children.

But back to Brexit the morning after.

The early texts. Miserable. I’m moving away from this wretched place. I’m moving to America (almost funny in retrospect; should add that I am married to an American); I am buying an island as far away as possible. There was one two plane rides away from Fiji for twelve grand apparently. I’ve searched it up.

The school run.

I have three boys, then five, twelve and fourteen. Smallest too small to grasp; Twelve thought the whole thing was just appalling (although one of his friends said the result was good because it meant we kept the pound) and Fourteen, I think, thought it was just typical of these grown ups to be not particularly watchful about something and then grouse. Or wail, in my case.

I left the house to take Five to school and two minutes down the road there was a triumphant woman assailing me. “It’s Independence Day!”

‘What does that funny lady mean?’ said Five. I tried to explain and he said, ‘But France is very nice and especially the train you put your car on.’

‘We got our country back!’ she hollered. Alarmingly similar in wording to Donald Trump’s comments in Scotland later that day, when congratulating them on voting for Brexit…

The rest of the run (I was snivelling by now) was full of moribund parents and I knew it was going to be a long day. It wasn’t even the voters I was cross with. It was, after all, their right to vote and, as I said above, I was entirely mindful of how opinions may have born of feeling eclipsed by a bossy elite. Maybe by bossy Oxbridgey Guardian readers like me, although I like to point out that I am actually very common and come from Welsh farming and mining stock for absolutely forever. Where the fact I have written novels is always going to be eclipsed by the size of Dai’s barbecue and the fact he is now a connoisseur of meat as well as a fan of Cameron, who GOT THE COUNTRY BACK ON ITS FEET. I did point out—that,you know, I’d hardly been head girl at Roedean; I was a bunker offer and swore with a passion—a couple of times in those early hours and days; for example, when someone called me a bad loser and said it was alright for me in my poncey house. I said, ‘I bought that as a semi derelict and washed up in the bath for four years and I am common. Yes, a right Chav. Yeah, okay I read all the time but…’ and I thought, ‘What nonsense am I even saying?’ and stopped in mid flight. My co-combatant smirked at me and, yes, I was a bad loser. I had conversations and made comments I should not have; that were divisive and snarky. I’m worrying I’m doing it now. Also, you saw my comments, above, about novels and the size of your barbecue. I realise that I am sliding more towards an exegesis of a dysfunctional family, but to tell you the truth, the familial schisms and the lies and the crazy rattling stuff that have gone on for decades, well now, they were melding that morning with Brexit ranting and Farage’s frog face and Boris’s snuffle-waffle-heffalump sounds. It was awful to feel so at odds with people who had been there a whole life, love them as I did, as I do. A beloved auntie just told me about how Theresa May is just what the country needs; my father in law is a Trump voter. God: WHAT A YEAR. How has that ‘renewal’ thing been going for you? Maybe TM will be out by the time this has published; I’d bet more on Trump, but I digress.

Around me, it felt—had been feeling for a while—like one great collective breakdown, that squalid summer. I wasn’t sure if I was actually okay. If anything was. Yet, I felt that I should not be smug about why I thought the vote was wrong. I had a secure home and had enough to keep me, us, safe and warm and it is plain as day that this is not the case for many, too many in our country. In some places and for some people, this will have inspired their choice of vote. You can’t go round jeering at others’ opinions when you have not walked in their shoes or heard of what was in their hearts. But I had read and thought a great deal and could not see any pressing reason to pursue Brexit. And as I said, it was those whom I felt had played fast and loose with facts and sums and hugely emotive topics that I was mad at. Well, and the Jingo woman on the school run.

And the fucking Bus That Couldn’t Do Maths.

24th June. Why did it have to be sports day? I felt it would be too sad to watch 421 primary age pupils while wondering how a decision we had made would impact on them. Fortunately, I didn’t see the Independence Day hullabaloo lady again, or I really would have done some very sweary public things, but when we were lining up, just after lunch, oh—people were miserable. Disconsolately dishing out squash for the kids and finding out where their eight year old was currently racing. All that week (I teach at secondary level) I went on to listen to angry teenagers, just not quite old enough to vote, bemoan the idiocy of what happened as more information and non-information came out; as Farage dismissed his endorsement of the facts on The Bus That Couldn’t Do Maths. It wasn’t that anyone was saying the EU had covered itself in glory, but mostly we were just confused, sad and, sometimes, a bit frightened—mostly, in my experience, because we witnessed a sense of empowerment from those holding views we found repellent: on the them and the us; the them you can’t trust; who take from us. I do realise I am simplifying, but I think that sense of witnessing loathing and suspicion and long held resentments coming to the fore was terrifying for people not used to dealing with it regularly. I should add that it is all very well for me to say; white; moreorless middle class enclave. Now I had to learn just a little of the kind of resilience that others are compelled to build every day.

Others. Yes. But us. We. Society is, should be, a we. Not us and (tick) other. Shouldn’t it be so? There I go again, worrying about semantic fields. But the words you use are important.

On Facebook ranting and hand wringing went on, as you’d expect. I blocked Independence Day lady. I should have known. She’d previously been posting that egregious thing about how we should be giving our funds to injured servicemen rather than the immigrants. That was a feature of those weeks. A sort of relegation to the back row of any sort of maths that made sense. If we don’t give the Polish bloke who runs the deli and works 100 hours a week a leg up, lazy sponger that he is, we will have funds for our lads. It’s The Bus That Couldn’t Do Maths, isn’t it? End our involvement in the EU and it is perfectly clear: straight swap with NHS funds and let’s get to Granny’s hip op and an end to the postcode lottery on, say, Tamoxifen. Anyway, the person with the sums was also joking about how she was playing ‘Spot the Brit’ while in the supermarket and titillating herself with the hilarity of someone asking the ‘foreign couple’ in front if they wanted help with packing their bags. HAHAHA I THOUGHT WE’D ALREADY TOLD THEM TO DO THIS.

Me: block. Pull plug. I cannot look. Oh look, though: she’s a good person because she’s put up another poster about hospices. Julie Burchill once wrote that shallow people cry very easily. Like at Bambi when mother deer gets it. I’ve found that racists do too and that they often like puppies and sick kids and doing their bit. I’ve always thought this is a bit like the Krays: they were ON IT when old ladies had their bags snatched or someone was mean to a defenceless kitten—and they probably contributed handsomely to the whist drive—but they still ran the firm and I wouldn’t have trusted them with my bread knife. There it is: I sound like a smug Guardian reader, I bet.

But back to sports day. Five smiled and waved and then up came the big cry. It was because I was thinking about what we might have taken from these children in terms of friendships made and bonds created; in terms of possibilities for living and studying and understanding. And I felt a dark and clawing sense of enclosure; of things drawing in around me. So I went into the toilets (I had to crouch down, obviously, because these things are built for small people) and I did the ugly cry, up from my toes. I probably wasn’t the only one.

It has been a strange year, summer 2016 to 2017, oh yes. My greatest cheer has come from the emboldening and charity of the young people I work with. The tears we have shared, even. I do believe we are seeing a generation becoming more alive to change and possibility and to the merits of political activism. And as I am fond of saying, it’s the parents you have to worry about. So thank you, thank you so much to all of you. But I worry about the young people and the children, of course. Mine; yours. I do not believe, as so many do—and they are broadcasting it on social media —that the world is now a terrible place; I don’t believe that. Or rather I believe that it has always been full of terrible things, but that I am optimistic, believe in the kindness of strangers and, to quote J. B. Priestly, that we ‘are one body’.

But we didn’t live in Merrie England until the spring of last year. Or at any time in the past. Speaking to some and listening to many, you’d think that’s what we were after. A return to a golden age; an Arcadia. Perhaps many Elizabethans may have had a whale of a time on all those junkets and national holidays; in gadding about round the maypole and sucking up mead in the days before twitter trolls and pesky plurality, but I’d argue it didn’t compensate for wars, poverty, pestilence and losing lots of your children. Perhaps The Bus That Couldn’t Do Maths needed a twin: The Bus That Made Up History. Well, something like that.

I do feel that, at this point in time, we, even we who perceive ourselves to be the original inhabitants of Albion (I am sorry; that was definitely a bit snarky of me), are tempest tossed and I hope, for all our children, that we—do you know, I am struggling with the word ‘we’ here; fretting that it is ethnocentric—are beginning to take stock and that, with clear thinking, proper information untainted by angry cant or prejudice born of sadness in these ‘alternate (sic) reality’ and ‘post truth’ times, with kindness and imagination we can make it to dry land. Off this rough journey out. You know, for the children.

For Five, Twelve, Fourteen.

Or should I say now, Six, Thirteen, Fifteen.

November 30, 2017

Give Sorrow Words

Here’s a funny little piece. It’s narrative non-fiction but, as you see, I may have twiddled with the conventions of that. Anyway, I submitted it for a journal and it wasn’t accepted – happens to us all, and anyway, nothing is wasted: so here. It’s for you. The story of me. Or of a me. I should warn you that it contains plain descriptions of demises, ways to go and funerals.

Give Sorrow Words

The things I have seen. What went missing; what was lost, sometimes unaccountably. And once upon a time, I was not able to give sorrow words. Therefore, it held; I couldn’t cradle it, talk to it and say, ‘Hello thing, what can you teach me?’

But, you see, I learned.

In my younger years, if I’d had the vocabulary, I’d have called the losses aphotic, Stygian in their darkness. But from the corner of my eye, and as the new world of words brewed alongside, I began instead to see them as navy; like a late twilight in indigo, with a little cyan, if you screwed up your eyes. Knew that from my paintbox. Soon, if I looked with the whole of my eye, I began to see wisps of lavender light in there. In desolate places and with people who should have cared, but no, I got big on ombre and subtle shifts in hue or pigment. I learned to observe. Just little things, like the turn of a face or a fold in a cushion, but the trappings of a world. In mourning for those who left with explanation, and those whose end was whispered or belied, I grew to usher forth more words as well as that colour and thus I limned my world. Do you know that the hour of death is a mossy green, sliding into turtle’s back? And it was cold, but not arctic, exactly. As for the folds in the cushion, well now if you gathered the fabric just a little deeper around them, you had the ravines for a miniature me; crevasse for a tiny arthropod. And I found that when I looked at Dead Mammy and Daddy in their coffins, it helped to see the prickly box-fabric as ecru or greige. Bit like them, at that point, if I don’t offend.

As a child, the worlds of dead and living collided; the worlds of truth and the imagination, too. But, in their way these losses were a fair prospect because by the time I was all grown up, I felt sort of brave in a way way that made me some sort of social oddity if I strayed into the wrong company or away from the Welsh plangency that loved the gob, or tang of death and what it yakked.

I learned when to live in an imagination and when to venture out.

And there were the colour and the growing word hoard, treasure box, I told you of.

In darkness, your eyes adjust, don’t they? And you see a star, however faint and think, ‘Aha, I am a sailor on my bark and from here I can navigate’ and you imagine yourself aeons back, confronting end times without the day-long tidy terrifying of our news; our always awake technology, screaming, ‘Apocalypse!’ Still, I might look at that word, even now, and wonder at it like new. Apocalypse: it’s from the ancient Greek, meaning uncovering. A word that once had much more celebratory nuances. Word hoard; colour; etymology and don’t worry there about some fellow thinking you’re a weirdy swot. Yes, loss; all the horrid redaction of my growing: its strange way of being gain. Me on my bark. In the dark. Ha! Or, as good Welsh poet, Henry Vaughn had it, I live again in dying, /And rich am I, now, amid ruins lying.

I was a kid, with the lady I loved best; Rachel Cariad, my godmother. She went, all puffed up from illness, playing the piano (true story) and at her funeral, her husband threw in a picture of their nasty dog with scoops of earth and wedding ring. My mother, the late sainted woman scowling now (watch out, sinners!) said, ‘He can be married to his mammy now’ and husband scuttled off with Mammy and ignored the other mourners and that was how it went. But I loved her, see? Rachel Cariad. He was a monster, kept chinchillas out back and he was a tower of wobbling flesh, coddled by Mammy at forty five and on burial day, it was time for spotted dick, Friday pudding, so home he went as Rachel Cariad lay in her pit and I wept and thought, ‘Yesterday I was a child, but today I am fully grown and I am fourteen and whatever happens now, I will never have to marry him and I will get away from my own mammy and I will do it for Rachel Cariad who was beautiful, divinely clever and all snuffed out young. And it wasn’t fair and where were you, Oh God, or you, Duw, I was praying to you by your cathedral, but what were you doing, you sudd drwg?’ And that means something like naughty fucker in the salt tongue and I can’t apologise for blasphemy because Jesus likes the ones with spirit who tangle and rage and mean it.

But it wasn’t enough, the rage, to stop him in his tracks, my Mr God. There were Grandma and Grandma again; one toes up in damp quiet hospital, Bristol way. Bristol granny was full of spite and when I was a tiny thing, she terrified me with winding sheets of tripe. In her unloving house were pickled eggs and nasty, wrinkling corpse-toe pickled onions and I felt, as a child, my childhood left at door and I had to be big and not scared. She burned things she didn’t like. Books; pictures; harridans from the village. At school, the grandmas were kindly old things, with sweets and soft stuff. Not in my line. Those were big and hard knuckled, but at least they taught me how to wrestle, good and hard. I won pounds, with the lads, though I never got off with them, like my pretty delicate friends with their weird, alive families. I was lost; I felt it like grief you see. But, my God now I see what it gifted me. The loss. I could stand staring into the future and there was nothing you could do to frighten me. Not a thing.

And second Grandma, whiz-pop in bed. I’d hoped she die seeing visions of the Virgin Mary, little white lady in the corner of a Pembrokeshire room, like my nanny did, but she just slipped back and sighed, off Cardiff Bay, so to speak, and it was a bit sad and lacked colour. And afterwards I went down Penarth beach, wading too deeply into the mud and roaring so the kids said, ‘Look there’s that weird’ and I said, to the wind off the sea, ‘But I’m not scared. There’s nothing you can take. I’m as old as the hills now I’m fifteen.’

I forgot Grandpa, under the damson tree, bottom of the ladder. Died doing what he loved, isn’t it? Well no, he died falling from a ladder and I wouldn’t choose that, boyo. I raged again, and Mr God he said, I heard him in a shoo-in off Cardigan Bay with the devil, he said, ‘There’s Catrin now’ (which was me) ‘and I’m proud of her, isn’t it, with that blasphemy and all because I like the ones who tangle and rage’ and we all know God is Welsh, of course.

You might think I was finished, but no. I’d been raised on terrible deaths on both sides. Falls from horses; at least two who never got out of bed and I heard whispering of overwork because they didn’t want to say insane and one disappeared, but I’m sure I saw shuffling out back; then another grandpa sloughed off quietly, quietly; oh and Daddy in my arms and that was the worst because he was spitting curses and saying, ‘Not you, not you. Why are you here?’ and I eighteen then, but old enough to be my own mother, and Mammy in hospital and keening ‘Where’s my boy, my special boy?’ when I rocked up at twenty, undergraduate and all, then I prayed by her grave and thought, ‘Oh why, she wouldn’t want me here’ and that was that. Give me my word hoard. Chasm. Sepulchre. Bag of liquorice allsorts to condole in an aniseed way.

Off the headland, St David’s way, there’s a field, bloody big, that’s all our own and it’s stuffed with my Llewhellins, poker straight and missing coracle shells, while the primroses push up around them and, time up, the blackberries come up all about, and that it’s the time for my aunt Muffled Myfanwy to visit her shot son, for his birthday. Her word hoard is in her head and she says, ‘My darling, my baby, why no. In carmine and ermine and beautiful days in the sod, my cliff child’—or something.

I startled you? I knew it. I grew up in the strangeness and in the death. But it wasn’t meant, my startling. I swear it’s the Cymraeg in me, or something. What I write about, I suppose I always knew, well it’s plangent, cruel dysfunction, is it not?

Ha! No, of course it isn’t. It’s survival and hoisting above your head this beautiful word hoard, like your standard and going, ‘Raaar!’ Merrily in two languages or more, with midnight blue and gunmetal garlands in the dark. I learned to give sorrow words. Not only words, but colour. Or imaginary friends. Literary creations. Beckett was excellent, but then so were the dead dears of Dylan Thomas. We had many chats when I was growing up. My nanny on the Cleddau, my great grandmother who smoked a pipe, spat and terrified the gentry, saw a little white woman in the corner for years and prayed with great aplomb to the Virgin Mary and death was actually scared of her. Everyone and everything was scared of Nanny. She taught me to see things. When she died, it was a scarring pain, but it was triumphant and that was a fine thing. Though I am not saying it can always be so.

People lie about what scares them. One friend has a theory that all in the women in Lycra on our school run are beset by an existential crisis. That they sweat off their no-faith with running and cappuccino afterwards at the gastro pub; if they run hard enough, they will outwit death. But then. My great Uncle Harry was the best wrestler this side of Tregarron; hard as nails, irresistible to women; oiled his chest just so. There were those who thought our Harry was immortal. But still he fell off the platform at Bristol Temple Meads and got crushed between buffers and it didn’t matter then about his washboard or how fast he could get to Llansteffan with the wind against him.

So yes loss: seen it so many times. It will happen again. In a quiet moment or on a balmy day when you’re going to a yellow beach. And I’ve seen those who didn’t care buff up the plate on a coffin and watched those who hoped for cash hoist a coffin: funerals are useful in that way, for me: a sorting device. You can tell a lot about a man by the way he behaves around an open casket. In my head, there are people I’ve banned from my own service already. But if I can’t control that, they’re at least off my Christmas card list: that’s a few seconds gained when I can, instead. write a card to crying eyes down the road who watches and wants company and love. There is a moment gained to help undo a folded lie. Now the reaper’s set you straight, that is. Yes, look: the bad man who corpse gloats and thinks he impresses; the cad who prays big and only in public; whose eyes are kind at the wake and whose flowers are devotion, not show? You go and think you’re mired in loss: in a terrible deficit. Of course; but there is benefit to accrue to you if only you are attentive. Scythe. Do some losing.

That title, at top. It’s from Macbeth, bard boy. It runs, ‘Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak knits up the o’er wrought heart and bids it break.’

Name, shape, hue: care for your own heart and devise a vocabulary for your loss, unique to you. It comes to us all, but with a word hoard you won’t be alone. Remember too, that in darkness, as I have seen, there are navy and lavender lights and a star which laughs.

November 24, 2017

An Indie Press Christmas!

October 31, 2017

Swamp Gonna Get You

Swamp Gonna Get You

‘Her freaks aren’t real.’

(Jane Bowles on Carson McCullers)

In a small town in Georgia, the Spanish moss cascades from the live oaks, the red earth is soft and warm; the benches are white. At this time of year, though, the grass has begun to parch and, by midday, the frames of the branches are hot to the touch. So, in such, it was good to be in the park with your Kool-Aid, sheltering in what less scorching enclaves you could find and catching the occasional spray from the fountain when a breeze came in your direction. And you want to be there rather than at the strip, with its hot respiring tarmac and its huge Piggly-Wiggly and CVS stores; but even more, you would not want to be on the other side of the town, away from the pretty centre, where green gave way to swamp and the fetid smell caught your nostrils in the summer.

At least that’s what the best ladies who lived on the best street said.

Down by the swamp lived old John Fogle; he stank, said the best ladies; he had, children said, the gift of second sight and, along with his cold, hostile wife and his unfriendly brood of female offspring, did not like people to stray their way. The children were at school but chose to play together, shunning the company or Missy or Mary Lee or Claudia. Did well in school, though. Top of the class, summa cum laude in the creatives, though the best ladies said these girls would never be scholars. Certainly, the other girls in the class tried to be friendly—the ones, that is, whose mothers had not warned them away from the Fogle girls. The ones with the kinder, more broad minded mothers but also those who wanted to rebel against their mothers—for this was also a town in which mean mindedness and snobbishness tended to run rife. And you heard about the best ladies already.

Today, one young girl was determined. Betty was kind, but also intent on one day getting down to the house and looking more closely at the swamp. And she persisted: “Can’t I come home and play with y’all? Ma says it’s o.k.”

“No. Pa wouldn’t allow it.”

“Why not? I’d be real good.”

“Don’t matter.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t know. Sump’n. Nothin. Can’t tell.”

This enigmatic last answer was all she needed. So she told her mother that she had

been invited home—and Mother allowed her because she, too, was kind and kind of curious to know about this family and, essentially, believed that they would treat right if treated right. She’d been spat out, too, by the best ladies. Didn’t fit, in gardening club and proper tea. So Betty followed, the girls trying to slough her off.

“Go away. Pa don’t like it!”

“Oh go on. You yella?”

“No. Well, if you’ll go away after.”

But, to the girls’ surprise, John Fogle, who had stood up poker-straight in a menacing way (Betty suddenly shuddering and regretting coming along), said that it would okay as long as she did not stay long. And in went Betty. Sure, the house and its moss-green plot were close to the swamp; you could smell the heavy air. But this place was somehow exotic and beautiful and a breath of fresh air after the tight little corner of town where Betty lived. And the house was tatty, but oddly welcoming and, well, fun. Yes, fun. Like anything could happen. Say…like a hand you couldn’t see, come to rub your back; a gator to rest your feet on; kind time slips where you don’t know when you are. And Betty liked it. Gradually, the girls began to play with their visitor to; chase and hide and go seek and, well, anything that took their fancy. And Betty met their mother who, in a startling and untidy way, was unexpectedly beautiful.

The girl stayed for the evening meal, too. Basic and old fashioned, but substantial, too. And, while no-one said much, Betty realised that she had been accepted. Maybe she would be able to go back. Other folks sucked, with their this and their that; table conversation and hoity toity.

Next day in school, the Fogle girls continued to play together only, but now they looked sideways at her with a hint of a smile. She felt happy. It was, in its way, all rather mysterious. She wondered, too, why John Fogle looked so old: more like a grandfather or even a great grandfather than a father. A tough life? But it seemed so happy there! The best ladies said dwellers in such environs drank bone broth and moonshine, so they looked like Methuselah. Well now. So I expect you, reader, would like to know a few answers, wouldn’t you? Well, the writer Carson McCullers, who came from Columbus, Georgia, wrote that she needed to return to the South from time to time to renew her sense of horror. It’s not that I generalise here, you know, but do you think she had a point? Because John Fogle was not the girl’s’ father and he did have the gift of second sight. The, seer and mystic, was the girls’ great grandfather and he had, for reasons and by folks we cannot name, been preserved for his gifts. And whether he drank bone broth and moonshine, or ate pippins and Chinese pear, he’s still be shining through, oh yes.

Father and grandfather? Gone. To the swamp one day. John Fogle saw what they would become.Told you that old brackish water was fetid. Not just that: it lived and breathed and did what it would do. And John Fogle was its custodian, being no murdering sort himself, exactly. Betty would be just fine because, as I told you, she was kind and looked without arrogance – only with spirit, love and curiosity at the world, in the way child and adult should. The Fogle house was a home of purity and spectral intelligence and out there, on the screened porch when the crickets sang? No finer. And those hoity toity mothers, the best ladies who lived on the best street on the other side of the park? Well, better not go the Fogle way. Swamp gonna get you. And Old John Fogle he gonna push you in and your Sunday glove come floating to the surface

Feasting and Fasting at the Great House

The old house, ...

Feasting and Fasting at the Great House

The old house, in the sleepy French village, is tall and dusty looking. Once, it must have been vibrant, but now, bindweed curls around it and ivy reclaims the windows and the stone of the house. It must be hard for the quiet inhabitants to see out. Sometimes, there is post for the house and the postboy makes a swift passage towards the door because the house alarms him. There is a housekeeper, an old crone who will not give you the time of day and, curiously, a gardener—though he never tends to the front gardens, so fallen into disrepair they must be. The villagers wonder whether there are beautiful and well tended lawns and pretty herbals to the rear of the house.

It is said that a lady lives at the house, some say two sisters, and that they never need company. But that this is a house of shadowy presences; a place where melancholy hangs thick in the air. And at night, sometimes—in summer when the top windows of the house are opened—one hears music, from a curious assortment of instruments: flute, cello, but also mandolin and dulcimer. And an inhabitant of the village making his way home could be stopped in his tracks because the music is so extraordinarily beautiful. And even so it sends a shiver up the spine which is not so pleasant. A death song you’re frightened you might not resist. A tune to lead you up the tenebrous dark spiral staircase of the self.

But today is different. People do not come and go readily in this village, but a new person has come, from the city, and he wants to enquire about the tall, great house. He thinks he might like to buy it: a retreat. It has great potential and he knows excellent architects and designers in Paris, where he lives now. He is bold, so he knocks at the door and it is answered. The rumour held true. Two women come to the door, so similar facially it is immediately clear that they are sisters. They are not beautiful, but they are arresting—I am sure you know the quality of which I speak: striking and sensual women, with poise and grace; exquisite manners, too. They seem pleased to see him and—he is surprised to entertain this peculiar thought for a moment—as if they knew he were coming.

Over tea and dainty little cakes, he explains to them what it is he is looking for. They are clearly amused by something but do not elaborate. And to his delight, they indicate quite clearly that, indeed, they were thinking of it, of perhaps finding somewhere smaller because the great house is too much to manage and they realise parts of it are in a poor state of repair. They tell him that they will be in touch, that they have a solicitor in Paris who attends to matters of estate and finance for them, and so the visitor takes his leave. His watched step brags.

So he waits and, sure enough, within weeks he hears from them again. A sum is agreed and the solicitors are instructed. Within two months, he is in the house, removing dust and grime and revealing the lovely house (he thinks) under the crumbling plaster and neglect. He has a lady in Paris and she becomes his wife. So taken with the house is he that he decides to move from Paris; it is a fair trip but he thinks he can make the journey once or twice a week to conduct his business. And during these times, his new wife is left lonely at home. The dream becomes more to his liking than to hers and, eventually, resentment begins to settle in the house.

The new wife sits and sulks; loathes her abode because he carved it. And her new husband. Sees herself deposited there, commodified. In time she rails aloud. After this, there is nowhere she can go. She is not of independent means. To return to her parents would be shame abominable, though she was never loved since cradle days. Her tears are insistent.

And so they come to her. The two sisters who are still there for, of course, they did not move out—just retreated into the deeper recesses of darkness until they saw a purpose. The housekeeper and gardener are there, too. They will never leave because the house is alive: it is a living breathing organism and they, hungry for blood and for dim, mysterious life, are part of its darkness. The house may be trimmed and tidied and made pretty but, underneath, it will not change. And so the young wife is taken to be with them. And when her husband, upstart from Paris, comes back, he will not find her. Eventually the house and its inhabitants will claim him too. For the new wife, it will be kind. Never loved since cradle days, she now finds company and subtle delight. And the satisfaction of this: knowing that his, her husband’s, will not be a quiet taking, for the sin of presuming to buy what belonged for ever to somebody else. For seeing only his own conspicuous consumption. Buying something that was never for sale. And all those who live in the wings of the house and in the fine rear garden will play their music, jangle the gold of our upstart, kiss the new wife and she them, and do what cruel things they must to survive and laugh. You could hear them if you went to this village on a summer night when the music is played. But keep your pride in check.

Cave Venus et Stellas

Cave Venus et Stellas

It is a strange place; a cold street, in which the temperature seems to drop as you round the corner. You feel the breeze cut into you; sometimes you think you must have imagined it, but no: there it is again. A street that looks the same as the last but inescapably and unfortunately, irresistibly different.

The young man, lean and callow, has been called upon to work for the shadowy residents of this street. There, every day, post is delivered, collected from doormats, papers from drives and houses and gardens maintained in apparently pristine condition. And yet, we see no one, telling ourselves only that the street’s inhabitants must keep, exotically, rather bohemian hours than ordinaries.

So, the young man is called to the fifth house on the street, a tall house, as all the others, with imposing gables and a tall, tall chimney stack. He rings the bell and a lady answers, ivory and willowy, with intense blue eyes. She sees him start just a little, as one does when confronted by such intense beauty. “Won’t you come in? So much to do.”

Inside, it is a world away from the modern suburban street, all billowing drapes, vast cabinets of dainty phials and bottles, Venetian mirrors and candelabra. And little cups; so many little cups on narrow shelves. With fluted saucers, Japanese and Chinese designs, lacquer work. His eye is drawn everywhere all at once and she senses this. “Yes: I am quite a collector, as you see.”

“Well, I’m wondering, Miss—is it Miss? (it is)—which jobs you need doing.”

“Ah, yes. But first, won’t you have some tea? Come through.”

The kitchen is through the long narrow hallway with its unusual intricate pattern of hexagonal tiles. The room has a surprisingly vast azure ceiling, upon which are painted many tiny gold stars. He would have thought it exquisite, had it not already begun to make him dizzy just looking at it for a short while. On the floor he thinks, counting quickly, that he sees hexagons, limned with a pretty language he does not know.

She boils water in an old fashioned urn (strange, he thought: why no kettle?); rather too much for tea for two. She makes tea in a lovely, highly polished silver tea pot—again it seems disproportionately large of scale.

“I need more shelves, Long thin shelves for my display. I am such a magpie, as you saw. And shallow cabinets for the walls. Like you could see in an old fashioned apothecary. For my pharmacopeia. Ha! But not so deep and, you know, with drawers. Can you picture what I mean?”

Yes, for the first. That shouldn’t be hard but her second request would be more difficult. He is too shy to say he cannot translate all her words. But, as he drinks his tea, he feels he wants to please her, so he agrees to start the job the next day. Although really, his other commitments tell him he should wait. It is something about this lady—and she amuses him too, he thinks as he drinks the tea from more of her little cups.

Next day, he begins and, in a day, the narrow shelves are cut and fitted for the rather bare little anteroom off the kitchen. “This will be my dining room,” she says, “You are decorating it for me.”

He drinks more of her tea, even eats some dainty little sandwiches she makes him, and begins work on the cabinets. The work seems to flow from him; oddly, some of his best work to date. Invisible joints and beautifully conceived design. He has surprised himself. But then, standing back from the room, as it begins to come to life with its first fittings, he feels suddenly tired and this she sees.

“Come and sit down. In the kitchen.”

“She looks more beautiful than ever today,” he thinks. But she’s his customer, so he must not say it aloud, though to think he might thrills him. And look at her milk-white tapering fingers; ancient, young: long nails. “Yes, I had better. I had better sit.” He is not himself, while her beauty swirls and fizzes stars.

He sits, closes his eyes for a moment to rest. He feels worse. Looking up at the ceiling and so at the fine golden stars, he becomes dizzier and dizzier. His extinction deeply pleasurable, before he sees and remembers no more. “Orris root and henbane, my darling” says she, stroking his cadaver and removing the cup and saucer from the still warm hand.

And now. The shadowy inhabitants of the rest of the houses in the street come through interconnecting doors -they are corporeal, after all—and they feast and they drink him dry from the little fluted cups as they sit under the stars. And what they cannot digest, they grind for their medicines and potions, even a dainty cosmetic for the ghostly pallor, and this they place in the shallow apothecaries’ drawers. Their pharmacopeia. Ha! And thus they retreat to their own homes and the lady with the lovely blue eyes is alone. Until, that is, she crosses her hall to the next visitor who will come to her, while she is floating, as she will be, across the fine encaustic tiles. And the tiles show not hexagons (oh poorly counting man!) but pentagons—no pentangles—and say, in the Latin inscription which our carpenter did not know how to read, “Cave Venus et Stellas.” And if you, too, cannot read this, then you must find out—just in case.