Jonathan Posner's Blog, page 12

October 2, 2020

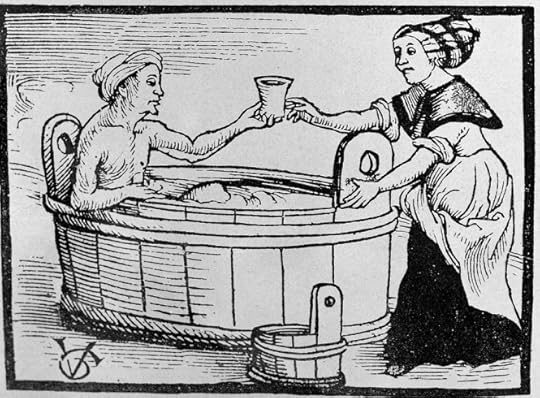

Tudor Bathtime

It was while I was happily soaking in the bath last night that I got to wondering about baths and hygiene in Tudor times – and what it meant to different levels of society. There’s this perception, perhaps, that people in the Tudor period were generally dirty, and that hygiene was not high on the list of priorities. To a certain extent, our visual media plays on this – either stretching our credibility with costume dramas showing impossibly beautiful people in impossibly pristine clothes (think BBC’s The Tudors), or presenting horribly grubby peasants in horribly filthy clothes (think Monty Python). We have also been fed this regular myth that Tudors thought bathing unhealthy; for example that even Elizabeth would bathe infrequently. I have not seen evidence of this; and she would have had access to the lavish bathrooms built in the main palaces by her father Henry VIII, so I think it much more likely that she bathed regularly.

The truth, as ever, is somewhere in between the ‘pristine’ and the ‘grubby’, and is a reflection of the rigid stratification of Tudor society. The nobles and royalty would bathe regularly – because they could. Unlike our egalitarian society, where having access to a bathroom is considered a basic human right across all of society, such access was considered a privilege. Upper classes had access to a physical bath – made of wood or possibly copper – as well as herbs, soap (made of olive oil), servants to heat the water on a fire, and means of disposing of the waste water. They also had the time available to relax in a bath.

The general population, however, did not have such access, but they recognised the need to keep as clean as they could – possibly more as a means of appearing to ‘better’ themselves than for hygiene reasons. Therefore they would either bathe in a stream, or hand wash themselves down with a bowl of water and animal fat soap. There was no means of disposing of the dirty waste water, so they would take it outside and pour it away down a hole (‘sink’). Like every household task we currently take for granted, the whole process was time-consuming and hard work. For people who had demanding lives and very little ‘down time’, personal hygiene probably only made it to the top of the priority list when the smell got too bad!

The theme of Tudor bathing occurs within both The Witchfinder’s Well and The Alchemist’s Arms. In the first, our heroine Justine takes a long leisurely scented bath in Tudor England, and in the second, she bathes in a clear stream (and has an amorous encounter, too!)

Both books are available on Amazon – click each cover to find out more.

August 25, 2020

Opiate of the masses?

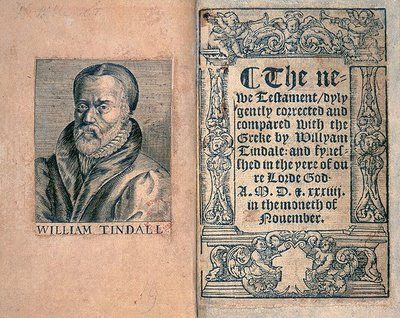

I thought it would be interesting to have an overview of religion as means of social control in Tudor times – and particularly the social implications of the shift from Catholicism to Protestantism.

Following Henry VIII’s break with Rome (the Reformation) and Cromwell’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the middle of the 16th century was a turbulent time for people of faith – which was pretty much every man, woman and child in the Realm. The question was, which faith?

There were those who clung to the ‘old’ religion – Catholicism and the leadership of the Pope in Rome, with its Latin Bible and highly ritualised services. This included, interestingly enough, the King himself, who never gave up his fundamentally Catholic belief – the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the Reformation were essentially economic and political constructs to give him money and the divorce he needed from Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn. Indeed, when William Tyndale published his English Bible, he was branded a heretic.

Then there were those that embraced the ‘new’ faith of Martin Luther and Calvin – the ‘Protestants’. In England it was primarily a stripped-back version of the same faith, with the differences being more socio-political than faith-based – it recognised the King as the head of the Church, it allowed for a Bible that could be read in English and therefore understood by the common people, and it avoided the corruption and patronage of Rome.

Martin Luther

Sure, there was more emphasis placed on elements such as transubstantiation (the bread and wine becoming the body and blood of Christ) being symbolic rather than real – but what Protestantism essentially did, was start to unpick one of the basic tenets of Feudalism – the control of the common people by the Church.

The Reformation and shift to Protestantism therefore gave people the chance to question the rights of the religious leaders to control social behaviour; and by allowing the people to engage in the church service in English, it gave them the chance to start thinking more for themselves.

John Calvin

This meant that the common people started to become more socially and politically curious – a movement that gathered more and more momentum and led, in part, to the Civil War in the 17th century.

Tudor Religion drives dramatic narrative

Not surprisingly for books set in the 1560s & 70s, the theme of religious fanaticism recurs throughout both The Witchfinder’s Well and The Alchemist’s Arms.

Both are available on Amazon – click each cover to find out more.

August 8, 2020

Clothing maketh man (and Woman)

We tend to focus so much of our historical spotlight on the Kings, Queens and nobles of the Tudor period – that we can perhaps be forgiven for thinking that Tudor costume was defined by the ladies and gentlemen who populated the Tudor Court.

But this is to miss the wide range of clothing styles and colours worn by the rest of the population. But, you ask, could they not wear similar clothes, or whatever they wanted? The answer is that they couldn’t – and this was governed not by social customs, but by the law!

And it was not just the clothes they wore, but also the food they ate, their jewellery and the furniture in their houses that were legally controlled.

The legislation was collectively called the Sumptuary Laws and it was designed to govern the amount people were allowed to spend on such things (the name derives from ‘sumptus’ – the latin for ‘expenditure’). But in truth, it actually enforced the strict stratification of society, keeping the ‘lower orders’ firmly in their place by ensuring they could be visually marked out by their clothing and food.

So, for example, nobody under the rank of Baron could line his hose with velvet or satin; nobody below a Knight wear a double ruff, carry a gilded sword or dagger. The penalty for breaking this law? At very least the confiscation of the offending item, but more likely a fine or imprisonment.

Most of these laws seemed to relate mainly to the very highest echelons of society – for example, Elizabeth’s Statute of Apparel in 1574 states that only a King, Queen and close Royal family could wear purple silk, cloth of gold and sable (although some Dukes, Marquises and Earls could use these as detailing on their outfits). Many other items of clothing and colours were also specified, together with the rank that could wear them.

So what did this mean for the common people? For the worker in the field it was largely irrelevant; they could not have afforded such fineries anyway. No, the people it really impacted were the aspiring Merchant class, becoming rich from trade, able to afford fine materials, but kept from wearing them through these rigid laws.

So ultimately, these were laws designed to keep the new middle class firmly in their place – and this they continued to do, with varying degrees of compliance, until English Civil War in the 1640s created a new kind of social order.

The sumptuary laws and clothing restrictions play a part in my series of Tudor time-travel historical novels.

Both books are available on Amazon UK:

The Witchfinder’s Well

The Alchemist’s Arms

Also available on Amazon.com:

The Witchfinder’s Well

The Alchemist’s Arms

August 2, 2020

Got it covered?

For the second time in as many months, I have entered the AllAuthor Cover of the Month contest. In June I entered The Alchemist’s Arms and got down to the last 100 – which pleased me as it seems the contest is about how many votes you can gather, rather than any intrinsic artistic merit in the cover design itself.

The original design for

The Witchfinder’s Well

The original design for

The Alchemist’s Arms

This month I have entered The Witchfinder’s Well – but not the cover I launched with the book (above), rather a new design recently uploaded to Amazon. It was, I admit, quite a wrench to move away from the original ‘moody girl in profile’ design – as I was quite emotionally attached to it. However, it has become increasingly clear to me that the genre my books are in – Tudor fiction with female lead – needs to have a woman in Tudor costume on the cover. So I have had both covers redesigned (below).

So what do you think of the new covers? Do they draw you in more? Do they make you want to buy / read each book more?

Are they now more readily identifiable in their genre of Tudor fiction with female lead?

Please do let me know.

And while you’re at it, please do vote for the cover on AllAuthor. It would be really great to make the last 100 again!

Please vote for my book in the AllAuthour Cover of the Month contest

Here’s a short video I made for the new covers!

Both books are available on Amazon UK:

The Witchfinder’s Well

The Alchemist’s Arms

Also available on Amazon.com:

The Witchfinder’s Well

The Alchemist’s Arms