Opiate of the masses?

I thought it would be interesting to have an overview of religion as means of social control in Tudor times – and particularly the social implications of the shift from Catholicism to Protestantism.

Following Henry VIII’s break with Rome (the Reformation) and Cromwell’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the middle of the 16th century was a turbulent time for people of faith – which was pretty much every man, woman and child in the Realm. The question was, which faith?

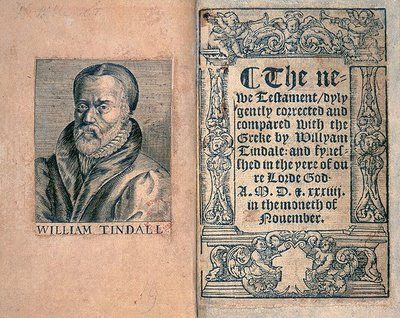

There were those who clung to the ‘old’ religion – Catholicism and the leadership of the Pope in Rome, with its Latin Bible and highly ritualised services. This included, interestingly enough, the King himself, who never gave up his fundamentally Catholic belief – the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the Reformation were essentially economic and political constructs to give him money and the divorce he needed from Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn. Indeed, when William Tyndale published his English Bible, he was branded a heretic.

Then there were those that embraced the ‘new’ faith of Martin Luther and Calvin – the ‘Protestants’. In England it was primarily a stripped-back version of the same faith, with the differences being more socio-political than faith-based – it recognised the King as the head of the Church, it allowed for a Bible that could be read in English and therefore understood by the common people, and it avoided the corruption and patronage of Rome.

Martin Luther

Sure, there was more emphasis placed on elements such as transubstantiation (the bread and wine becoming the body and blood of Christ) being symbolic rather than real – but what Protestantism essentially did, was start to unpick one of the basic tenets of Feudalism – the control of the common people by the Church.

The Reformation and shift to Protestantism therefore gave people the chance to question the rights of the religious leaders to control social behaviour; and by allowing the people to engage in the church service in English, it gave them the chance to start thinking more for themselves.

John Calvin

This meant that the common people started to become more socially and politically curious – a movement that gathered more and more momentum and led, in part, to the Civil War in the 17th century.

Tudor Religion drives dramatic narrative

Not surprisingly for books set in the 1560s & 70s, the theme of religious fanaticism recurs throughout both The Witchfinder’s Well and The Alchemist’s Arms.

Both are available on Amazon – click each cover to find out more.