Jonathan Posner's Blog, page 2

February 10, 2025

16th Century ‘Landsknechts’

When it comes to historical accuracy, Hollywood is a mixed bag. If Hollywood is to be believed, medieval warfare lasted from 300 to 1700 AD and mostly took place in foggy forests and swamps. Men in dirty armour and woollen chainmail fought one-on-one, having forgotten to put on their helmets or their tabards. They hacked each other to death with swords, axes, maybe crossbows, and it never occurred to them that maybe they could use some gunpowder, or that a formation of some kind would protect them. No doubt they left their brains at home, next to the helmet and the tabard.

When it comes to historical accuracy, Hollywood is a mixed bag. If Hollywood is to be believed, medieval warfare lasted from 300 to 1700 AD and mostly took place in foggy forests and swamps. Men in dirty armour and woollen chainmail fought one-on-one, having forgotten to put on their helmets or their tabards. They hacked each other to death with swords, axes, maybe crossbows, and it never occurred to them that maybe they could use some gunpowder, or that a formation of some kind would protect them. No doubt they left their brains at home, next to the helmet and the tabard.

This is a shame, as the world of the landsknecht was as colourful as it was dangerous, and a good formation is very satisfying to watch. What would a movie about Roman legionaries be, without the classic tortoise formation?

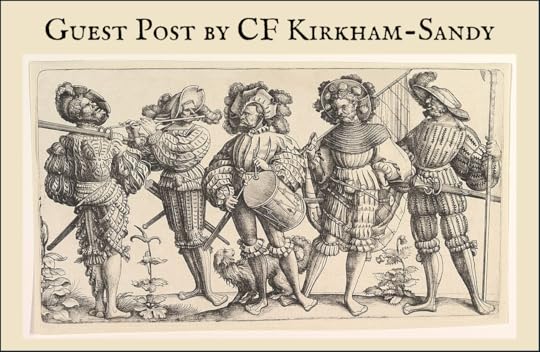

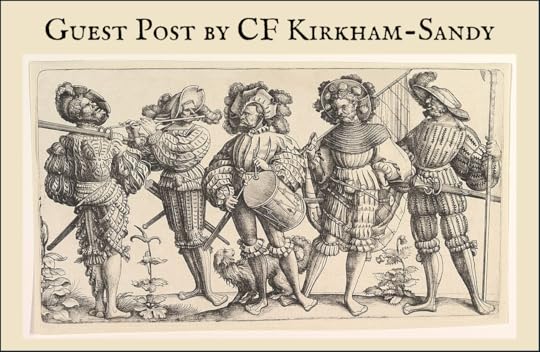

Landsknecht with his wife, engraved by Daniel Hopfer

The word landsknecht (‘servant of the land’) first appears in 1486. Maximilian I had realised that his armies’ organisation and tactics were ineffective, so he cribbed from the Swiss. He recruited pikemen from his territories in South Germany and gave them new training under a Swiss captain. The result was two new regiments, totalling six to eight thousand men.

Unfortunately for Maxmilian and his successors, the landsknechts took something else from the Swiss: the right to choose their own employer, and the right to recruit others to serve that employer. They based this right on ancient customs.

Unlike France and England, Italy and Germany were far from centralised. Italy was a mixture of duchies, republics and principalities. Germany’s political map – a complex mosaic that is almost tiring to look at – makes Italy’s look stable and straightforward in comparison. National identities are fluid, tenuous things, and in the modern day we take it for granted that a nation is represented on a map by a state. Germany and Italy were ideas, names given to regions. We think of Erasmus as Dutch, but at the time he was called ‘the German Socrates’.

Each tiny piece of that German mosaic represents a different prince with his own ambitions, ideas, and beliefs. The more princes there are, the harder it becomes to enforce religious unity. When threatened, religious dissidents can simply hop the border and enter the jurisdiction of a different duke. Alone, a duke might have difficulty defying the emperor, but the German states knew there was strength in numbers, forming alliances like the Schmalkaldic League.

The prince-employer bought his landsknechts in units called standards (or ensigns). He would then choose a colonel from among the landsknechts and give him letters patent – orders to recruit a fixed number of troops. The colonel needed permission from local magnates to recruit in their territory – but in a region as divided as Germany, that was not hard to obtain.

Etching by Daniel Hopfer

Each company had a captain, so the captains roamed the area, equipped with fifes, drums, and commission papers. If a willing recruit looked suitable, his details were written down on the muster roll: name, age, birthplace, and primary weapon. The recruit would be given the location of the company’s place of assembly and told when he needed to be there to muster.

The captain would choose an open space as the place of assembly. Then he would stick two halberds upright in the ground and lay a pike across them, making a rectangular doorway. When the recruits arrived, they would form ranks behind this rectangle. One by one, they would step through the doorway, a bit like going through the metal detector at the airport. The men and their weapons would be examined, to see if both were in good working order. From this process we get the phrase ‘to pass muster’. Once the muster was complete, everyone formed a circle around the colonel and he read aloud a letter of articles: the terms and conditions.

Captains could be confident they would find enough willing recruits. The sixteenth century was a time of economic hardship. Depopulation caused by the Black Death had improved the bargaining power of labourers in the later medieval period. By the sixteenth century the population was back up, and so now labour was plentiful instead of scarce. That meant high unemployment and a fall in living standards, because those with work saw their stagnant income eroded by inflation.

A pikeman could expect around 3 ducats a month, but skilled warriors could bargain for more. Fighting on the front line came with the highest risk and the highest reward: the men in the front lines were doppelsoldner, or double-pay-men. If your name was entered on the muster roll, you got conduct money to cover the cost of travelling to the place of assembly. Captains could also earn a little extra by cheating: they were paid for each name, so some of the men on the muster rolls didn’t exist. Having a muster at a place of assembly helped to counteract this: if men didn’t turn up, they would have to be struck off the roll.

The structure of Italian society made long-term recruitment of troops more difficult than in other countries. They tended to employ mercenaries instead of being them. Famously, Machiavelli loathed mercenaries. He had learned the hard way that mercenaries can desert at a critical moment. He argued that a prince could still use mercenaries effectively, but only to invade another prince’s territory – never to defend his own. A prince should put his territory’s defence in the hands of his citizens. They could be relied upon when the battle got desperate – because they would be fighting for the security of their homes, their families, their churches, their crops.

But mercenaries still demanded discipline and internal order in their companies. After the colonel had read the letter of articles, landsknechts sealed their service with oaths. Standard-bearers had an additional oath to defend the company’s standards at all costs.

There was a hierarchy within an army of landsknechts. At the top was the colonel, answering to the prince-employer. Answering to the colonel was the lieutenant-colonel, and the captains answered to the lieutenant-colonel. Each company had a quartermaster called a harbinger and a surgeon. Surgeons were highly skilled at operating – they could amputate a leg in under a minute – but infection was a major killer. The provost oversaw discipline, and he brought troublemakers before the Justizamptmann – the bailiff. (Also known as a Schultheiss.) The bailiff enforced martial law. He selected the jury and the court martial officers. If the jury found the accused guilty, the bailiff sentenced him.

Landsknechts were not exempt from the rules of war. Priests, women, and churches must be spared – and if you were inside a church, you were forbidden from selling alcohol when the priest was holding a service. Gambling and drunkenness were also forbidden, to prevent fights from breaking out among the ranks. Landsknechts were not permitted to continue feuds in the name of their personal honour.

Under the stress of supply problems, order crumbled. It was not easy to keep landsknechts well fed and well-paid. Mills were a vital piece of infrastructure, the places where grain could be turned into flour, but rampaging armies targeted them in order to starve the enemy. In 1527, unpaid mercenaries mutinied and sacked Rome – shaming their employer, Emperor Charles V. To add insult to injury, the landsknechts scrawled LUTHER on the frescoes of the papal palace.

Despite their reputation for unreliability, cowardice and desertion carried the death penalty. Of course, in the heat of battle, there was no time for a court martial, so panicking deserters were killed by their fellow soldiers. Before battle, some landsknechts had a ritual to purify themselves: they threw mud over their shoulder, rather like the superstition of throwing salt over the shoulder today.

Each landsknecht had to own his own weapons: no sharing, no borrowing. Armour and weapons could be decorated with religious symbols or erotic imagery. Weapons made beautiful gifts: Erasmus was a total civilian, but he owned a long dagger called a baselard, the scabbard decorated with a design by Holbein.

Battle Scene – After Hans Holbein the Younger.

Each landsknecht had a sword for his secondary weapon. For his primary weapon, he would have a pike, a zweihander, a halberd, or an arquebus. Most landsknechts were pikemen. The pike was eighteen feet of ash tipped with a steel spearhead, so it allowed the pikeman to hold off his enemy at some distance. Pikemen were effective against infantry and essential for breaking cavalry charges. Welsh pikemen helped put Henry VII on the throne in 1485.

Landsknechts used a square formation called gevierte Ordnung (fourth order). A formation could include up to ten thousand men. Usually, landsknechts drew up in three squares, called igels – igel means hedgehog. Each of the four sides of the square had three outward-facing rows of pikemen.

If pikes weren’t enough to hold back the enemy cavalry, halberdiers with their billhooks could come to the aid of the pikemen. A halberd is a three-in-one spear, axe and billhook, usually around eight feet long. If the horse reached within eighteen feet- past the pike points- the billhook could be used to unseat the rider. Landsknechts with zweihanders could also protect pikemen: the weight and length of zweihanders meant they could be swung around to knock aside the weapons of the enemy. According to the Burgundian chronicler Jean Molinet, it was a halberd that killed Richard III. Given the versatile nature of the weapon, the different wounds on Richard’s skull could have been made by halberds.

Arquebuses (also known as hackbuts) could cut down cavalry with their fire, but loading and firing an arquebus is a slow and fiddly business demanding both hands. An arquebusier preparing his weapon for the next shot is vulnerable. So, pikemen and arquebusiers worked well together. The arquebusier takes down the horse before he can reach the pikeman, and the pikeman guards the arquebusier from attack.

Landsknechts didn’t have formal uniforms, but their colourful clothes are distinctive. The troops of Giovanni de Medici wore mourning sashes permanently after his death, and the colour contrast would have been striking. Landsknechts could go up to a month without changing these clothes, as there wasn’t much by way of laundry facilities for an army on the move. This isn’t quite as awful as it sounds: early modern clothes were made from linen and wool and were far more breathable than modern synthetic fabrics. Over the top, thick leather coats could protect the landsknecht from cuts and slashes.

And perhaps, those huge feathers in his hat brought him a little cheer as he rode off to war.

Further reading:

The King’s Painter: The Life and Times of Hans Holbein by Franny Moyle

The Beauty and the Terror: An Alternative History of the Italian Renaissance by Catherine Fletcher

“The Landsknecht: His Recruitment and Organization, With Some Reference to the Reign of Henry VIII.” Military Affairs, vol. 35, no. 3 (1971) pp. 95–99, by John Gilbert Miller.

CF Kirkham-Sandy is the author of the Tudor novel Shackled to a Ghost, now available on Amazon US, Amazon UK and Kindle Unlimited (search on Amazon using code B0DV5F6585).

CF Kirkham-Sandy grew up in Devon and has a BA and an MA in History from the universities of York and Bristol. CF lives and works in Herefordshire, and moonlights as a history tutor for students of all ages. CF is currently writing another novel and can be found on Threads @kirkhamsandycf and Twitter @Catofthepigeons.

The post 16th Century ‘Landsknechts’ appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

Guest Post – 16th Century ‘Landsknechts’ (German mercenaries)

When it comes to historical accuracy, Hollywood is a mixed bag. If Hollywood is to be believed, medieval warfare lasted from 300 to 1700 AD and mostly took place in foggy forests and swamps. Men in dirty armour and woollen chainmail fought one-on-one, having forgotten to put on their helmets or their tabards. They hacked each other to death with swords, axes, maybe crossbows, and it never occurred to them that maybe they could use some gunpowder, or that a formation of some kind would protect them. No doubt they left their brains at home, next to the helmet and the tabard.

When it comes to historical accuracy, Hollywood is a mixed bag. If Hollywood is to be believed, medieval warfare lasted from 300 to 1700 AD and mostly took place in foggy forests and swamps. Men in dirty armour and woollen chainmail fought one-on-one, having forgotten to put on their helmets or their tabards. They hacked each other to death with swords, axes, maybe crossbows, and it never occurred to them that maybe they could use some gunpowder, or that a formation of some kind would protect them. No doubt they left their brains at home, next to the helmet and the tabard.

This is a shame, as the world of the landsknecht was as colourful as it was dangerous, and a good formation is very satisfying to watch. What would a movie about Roman legionaries be, without the classic tortoise formation?

Landsknecht with his wife, engraved by Daniel Hopfer

The word landsknecht (‘servant of the land’) first appears in 1486. Maximilian I had realised that his armies’ organisation and tactics were ineffective, so he cribbed from the Swiss. He recruited pikemen from his territories in South Germany and gave them new training under a Swiss captain. The result was two new regiments, totalling six to eight thousand men.

Unfortunately for Maxmilian and his successors, the landsknechts took something else from the Swiss: the right to choose their own employer, and the right to recruit others to serve that employer. They based this right on ancient customs.

Unlike France and England, Italy and Germany were far from centralised. Italy was a mixture of duchies, republics and principalities. Germany’s political map – a complex mosaic that is almost tiring to look at – makes Italy’s look stable and straightforward in comparison. National identities are fluid, tenuous things, and in the modern day we take it for granted that a nation is represented on a map by a state. Germany and Italy were ideas, names given to regions. We think of Erasmus as Dutch, but at the time he was called ‘the German Socrates’.

Each tiny piece of that German mosaic represents a different prince with his own ambitions, ideas, and beliefs. The more princes there are, the harder it becomes to enforce religious unity. When threatened, religious dissidents can simply hop the border and enter the jurisdiction of a different duke. Alone, a duke might have difficulty defying the emperor, but the German states knew there was strength in numbers, forming alliances like the Schmalkaldic League.

The prince-employer bought his landsknechts in units called standards (or ensigns). He would then choose a colonel from among the landsknechts and give him letters patent – orders to recruit a fixed number of troops. The colonel needed permission from local magnates to recruit in their territory – but in a region as divided as Germany, that was not hard to obtain.

Etching by Daniel Hopfer

Each company had a captain, so the captains roamed the area, equipped with fifes, drums, and commission papers. If a willing recruit looked suitable, his details were written down on the muster roll: name, age, birthplace, and primary weapon. The recruit would be given the location of the company’s place of assembly and told when he needed to be there to muster.

The captain would choose an open space as the place of assembly. Then he would stick two halberds upright in the ground and lay a pike across them, making a rectangular doorway. When the recruits arrived, they would form ranks behind this rectangle. One by one, they would step through the doorway, a bit like going through the metal detector at the airport. The men and their weapons would be examined, to see if both were in good working order. From this process we get the phrase ‘to pass muster’. Once the muster was complete, everyone formed a circle around the colonel and he read aloud a letter of articles: the terms and conditions.

Captains could be confident they would find enough willing recruits. The sixteenth century was a time of economic hardship. Depopulation caused by the Black Death had improved the bargaining power of labourers in the later medieval period. By the sixteenth century the population was back up, and so now labour was plentiful instead of scarce. That meant high unemployment and a fall in living standards, because those with work saw their stagnant income eroded by inflation.

A pikeman could expect around 3 ducats a month, but skilled warriors could bargain for more. Fighting on the front line came with the highest risk and the highest reward: the men in the front lines were doppelsoldner, or double-pay-men. If your name was entered on the muster roll, you got conduct money to cover the cost of travelling to the place of assembly. Captains could also earn a little extra by cheating: they were paid for each name, so some of the men on the muster rolls didn’t exist. Having a muster at a place of assembly helped to counteract this: if men didn’t turn up, they would have to be struck off the roll.

The structure of Italian society made long-term recruitment of troops more difficult than in other countries. They tended to employ mercenaries instead of being them. Famously, Machiavelli loathed mercenaries. He had learned the hard way that mercenaries can desert at a critical moment. He argued that a prince could still use mercenaries effectively, but only to invade another prince’s territory – never to defend his own. A prince should put his territory’s defence in the hands of his citizens. They could be relied upon when the battle got desperate – because they would be fighting for the security of their homes, their families, their churches, their crops.

But mercenaries still demanded discipline and internal order in their companies. After the colonel had read the letter of articles, landsknechts sealed their service with oaths. Standard-bearers had an additional oath to defend the company’s standards at all costs.

There was a hierarchy within an army of landsknechts. At the top was the colonel, answering to the prince-employer. Answering to the colonel was the lieutenant-colonel, and the captains answered to the lieutenant-colonel. Each company had a quartermaster called a harbinger and a surgeon. Surgeons were highly skilled at operating – they could amputate a leg in under a minute – but infection was a major killer. The provost oversaw discipline, and he brought troublemakers before the Justizamptmann – the bailiff. (Also known as a Schultheiss.) The bailiff enforced martial law. He selected the jury and the court martial officers. If the jury found the accused guilty, the bailiff sentenced him.

Landsknechts were not exempt from the rules of war. Priests, women, and churches must be spared – and if you were inside a church, you were forbidden from selling alcohol when the priest was holding a service. Gambling and drunkenness were also forbidden, to prevent fights from breaking out among the ranks. Landsknechts were not permitted to continue feuds in the name of their personal honour.

Under the stress of supply problems, order crumbled. It was not easy to keep landsknechts well fed and well-paid. Mills were a vital piece of infrastructure, the places where grain could be turned into flour, but rampaging armies targeted them in order to starve the enemy. In 1527, unpaid mercenaries mutinied and sacked Rome – shaming their employer, Emperor Charles V. To add insult to injury, the landsknechts scrawled LUTHER on the frescoes of the papal palace.

Despite their reputation for unreliability, cowardice and desertion carried the death penalty. Of course, in the heat of battle, there was no time for a court martial, so panicking deserters were killed by their fellow soldiers. Before battle, some landsknechts had a ritual to purify themselves: they threw mud over their shoulder, rather like the superstition of throwing salt over the shoulder today.

Each landsknecht had to own his own weapons: no sharing, no borrowing. Armour and weapons could be decorated with religious symbols or erotic imagery. Weapons made beautiful gifts: Erasmus was a total civilian, but he owned a long dagger called a baselard, the scabbard decorated with a design by Holbein.

Battle Scene – After Hans Holbein the Younger.

Each landsknecht had a sword for his secondary weapon. For his primary weapon, he would have a pike, a zweihander, a halberd, or an arquebus. Most landsknechts were pikemen. The pike was eighteen feet of ash tipped with a steel spearhead, so it allowed the pikeman to hold off his enemy at some distance. Pikemen were effective against infantry and essential for breaking cavalry charges. Welsh pikemen helped put Henry VII on the throne in 1485.

Landsknechts used a square formation called gevierte Ordnung (fourth order). A formation could include up to ten thousand men. Usually, landsknechts drew up in three squares, called igels – igel means hedgehog. Each of the four sides of the square had three outward-facing rows of pikemen.

If pikes weren’t enough to hold back the enemy cavalry, halberdiers with their billhooks could come to the aid of the pikemen. A halberd is a three-in-one spear, axe and billhook, usually around eight feet long. If the horse reached within eighteen feet- past the pike points- the billhook could be used to unseat the rider. Landsknechts with zweihanders could also protect pikemen: the weight and length of zweihanders meant they could be swung around to knock aside the weapons of the enemy. According to the Burgundian chronicler Jean Molinet, it was a halberd that killed Richard III. Given the versatile nature of the weapon, the different wounds on Richard’s skull could have been made by halberds.

Arquebuses (also known as hackbuts) could cut down cavalry with their fire, but loading and firing an arquebus is a slow and fiddly business demanding both hands. An arquebusier preparing his weapon for the next shot is vulnerable. So, pikemen and arquebusiers worked well together. The arquebusier takes down the horse before he can reach the pikeman, and the pikeman guards the arquebusier from attack.

Landsknechts didn’t have formal uniforms, but their colourful clothes are distinctive. The troops of Giovanni de Medici wore mourning sashes permanently after his death, and the colour contrast would have been striking. Landsknechts could go up to a month without changing these clothes, as there wasn’t much by way of laundry facilities for an army on the move. This isn’t quite as awful as it sounds: early modern clothes were made from linen and wool and were far more breathable than modern synthetic fabrics. Over the top, thick leather coats could protect the landsknecht from cuts and slashes.

And perhaps, those huge feathers in his hat brought him a little cheer as he rode off to war.

Further reading:

The King’s Painter: The Life and Times of Hans Holbein by Franny Moyle

The Beauty and the Terror: An Alternative History of the Italian Renaissance by Catherine Fletcher

“The Landsknecht: His Recruitment and Organization, With Some Reference to the Reign of Henry VIII.” Military Affairs, vol. 35, no. 3 (1971) pp. 95–99, by John Gilbert Miller.

CF Kirkham-Sandy is the author of the Tudor novel Shackled to a Ghost, now available on Amazon US, Amazon UK and Kindle Unlimited (search on Amazon using code B0DV5F6585).

CF Kirkham-Sandy grew up in Devon and has a BA and an MA in History from the universities of York and Bristol. CF lives and works in Herefordshire, and moonlights as a history tutor for students of all ages. CF is currently writing another novel and can be found on Threads @kirkhamsandycf and Twitter @Catofthepigeons.

The post Guest Post – 16th Century ‘Landsknechts’ (German mercenaries) appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

January 22, 2025

Mary Fox is back!

My new Mary Fox book is now up on Amazon to pre-order!

My new Mary Fox book is now up on Amazon to pre-order!

The River of Fire is the third adventure for action heroine Mary Fox (think Jack Reacher but 16th century and female  ).

).

“Mary Fox’s latest adventure takes her to Italy in the company of the dashing Angelo di Luca. With danger at every turn, enemies both old and new, and twist after twist, this starts as a very good story and ends as a gripping read that I couldn’t put down. I loved it.” Elizabeth Ducie, Author.

Pre-order your copy on Amazon

Fleeing England to evade the authorities, Mary Fox knows her reputation for outsmarting death will be tested like never before. Agreeing to help the handsome Angelo di Luca return his family’s stolen jewel may just have been a mistake. But there’s no time for regrets; now it’s all about survival. A determined enemy shadows their every move, seeking murderous revenge.

From misty Dutch canals to treacherous Alpine peaks, through the crowded streets of Milan to the grand palazzos of Florence, Mary finds herself in a deadly game of cat and mouse with her cunning adversary. Each safe house could be a trap, each ally a potential betrayer.

In Florence, Mary gets caught up in a deadly (real life) plot against Duke Alessandro de Medici, and is held a prisoner. Can she escape before the deadline to return the jewel runs out? And will it be her enemy that seals her fate, or an explosive eruption of fiery lava lurking under the Bay of Naples?

In this deadly dance of shadows and fire, has the legendary Mary Fox finally met her match?

Pre-order your copy on Amazon.

The post Mary Fox is back! appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

January 17, 2025

The Thursday Book Club – Jan 25

The latest edition of The Thursday Book Club was broadcast on 16th January 2025 at 2pm on Phonic FM. Joining host Jonathan Posner was Jason Mann. Click the names to find out more about them, and use the audio bar below to listen to the full show.

The latest edition of The Thursday Book Club was broadcast on 16th January 2025 at 2pm on Phonic FM. Joining host Jonathan Posner was Jason Mann. Click the names to find out more about them, and use the audio bar below to listen to the full show.

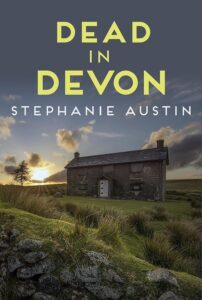

We reviewed Dead in Devon by Stephanie Austin.

We reviewed Dead in Devon by Stephanie Austin.

We had an interview with Orlando Murrin, author of Knife Skills for Beginners, and the upcoming Murder Below Deck.

The interview was also videoed, so you can watch it by clicking on the thumbnail below.

Our discussion was on: Plotters v Pantsers.

Who favours plotting? Who favours Pantsing?

What does it even mean??

Listen to the show in full here:

https://jonathanposnerauthor.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/TBC-Show-17-16-01-25.mp3The next show is at 2pm on the 20th February 2025.

NEWS The Passenger Manifest by Rebecca Southgate Williams came out on 10 December 2024. Here’s the blurb: Glimpses into other people’s lives are rarely what they seem – but offered the chance to journey awhile with someone, is it ever possible to figure out who they really are? Step aboard and accompany an array of characters over the course of a year as they travel by train through changing landscapes and seasons, each carrying their own dreams, desires and secrets. Whether travelling to reunions or conferences, visiting family or friends, or even manufacturing their own dangerous liaisons, each has something to hide, and something to prove. Hurtling on to their final destinations, their paths twist and collide, shattering carefully constructed facades to reveal their inner lives and intricate lies. When catastrophe strikes, will anyone emerge unscathed?

The Passenger Manifest by Rebecca Southgate Williams came out on 10 December 2024. Here’s the blurb: Glimpses into other people’s lives are rarely what they seem – but offered the chance to journey awhile with someone, is it ever possible to figure out who they really are? Step aboard and accompany an array of characters over the course of a year as they travel by train through changing landscapes and seasons, each carrying their own dreams, desires and secrets. Whether travelling to reunions or conferences, visiting family or friends, or even manufacturing their own dangerous liaisons, each has something to hide, and something to prove. Hurtling on to their final destinations, their paths twist and collide, shattering carefully constructed facades to reveal their inner lives and intricate lies. When catastrophe strikes, will anyone emerge unscathed?

If you loved ‘Girl on a Train’ or ‘Sorrow and Bliss’, this could be one for you!

Available on Amazon.

The audiobook of Lizzie Fry’s novel Little Boy Missing launches today (January 16th). It’s a gripping psychological thriller about a little boy who goes missing, and the mum is the main suspect – but she didn’t do it.

The audiobook of Lizzie Fry’s novel Little Boy Missing launches today (January 16th). It’s a gripping psychological thriller about a little boy who goes missing, and the mum is the main suspect – but she didn’t do it.

Available on Amazon.

The Teignmouth and Dawlish Area Literary and Cultural Society published Write Way Up on the 29th December last year. It’s an anthology of 24 fictional and non-fiction ‘shorts’ penned by members of the writers’ group. They meet monthly to share their writing efforts, prompted by a pre-agreed theme. More information about them can be found on the newly launched TADALACS website tadalacs.co.uk.

The Teignmouth and Dawlish Area Literary and Cultural Society published Write Way Up on the 29th December last year. It’s an anthology of 24 fictional and non-fiction ‘shorts’ penned by members of the writers’ group. They meet monthly to share their writing efforts, prompted by a pre-agreed theme. More information about them can be found on the newly launched TADALACS website tadalacs.co.uk.

Available on Amazon.

Author J T Scott has a new story in her Bumper the Bumblebee and Friends series. It’s called Bessie the Badger and Friends and follows the woodland creatures on an egg hunt with a positive message for children that good things can come even when it all seems broken and bad.

Author J T Scott has a new story in her Bumper the Bumblebee and Friends series. It’s called Bessie the Badger and Friends and follows the woodland creatures on an egg hunt with a positive message for children that good things can come even when it all seems broken and bad.

It’s available on Amazon, as both a standard paperback and a colouring activity book.

Kathryn Haydon is giving us advanced warning of a new novel due out in the spring. It’s called Call of the Sandpiper and is a romance set against the glorious backdrop of Woolacombe, North Devon. I’m sure Kathryn will give us more info on this book nearer the launch.

For the writers among you, the next FREE Writing at the Edge webinar is on February 6th. Titled The Art of Dialogue it will cover crafting natural and engaging dialogue that drives the story forward and develops characters.

The post The Thursday Book Club – Jan 25 appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

December 23, 2024

My Story Long-listed for Award!

Very excited! One of my short stories is in a book that’s up for an award!

Beneath a Midwinter Moon is on the long-list for a 2025 Chanticleer Award. The book is an anthology of short stories by me and my fellow Paper Lantern Writers. My story is a follow-on from The Witchfinder’s Well, telling how one of the key villains from that book comes back to cause more trouble for the heroine and her family at Christmas.

The winners will be announced in the spring – so fingers crossed!

Meanwhile, if you’ve read The Witchfinder’s Well and want more of the story, then download or order a copy of Beneath a Midwinter Moon. Here’s the link.

The post My Story Long-listed for Award! appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

December 21, 2024

The Thursday Book Club – Dec 24

The latest edition of The Thursday Book Club was broadcast on 19th December 2024 at 2pm on Phonic FM. Joining host Jonathan Posner was Su Bristow. and Cathie Hartigan. Click the names to find out more about them, and use the audio bar below to listen to the full show.

The latest edition of The Thursday Book Club was broadcast on 19th December 2024 at 2pm on Phonic FM. Joining host Jonathan Posner was Su Bristow. and Cathie Hartigan. Click the names to find out more about them, and use the audio bar below to listen to the full show.

We reviewed Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan.

Our discussion was on: Creating great characters: How to create multi-dimensional characters that resonate with readers?

The next show is at 2pm on the 16th January 2025.

NEWS  For All Your Endeavours by David Sharp is a captivating tale of murder in the most unexpected of places. When a ‘bog body’ is discovered in Dartmoor, local archaeologists are thrilled by the unusual find. But when the body is identified as a cold case murder victim, detectives must unravel a murky web of forbidden love and family tragedy as they attempt to uncover the truth.

For All Your Endeavours by David Sharp is a captivating tale of murder in the most unexpected of places. When a ‘bog body’ is discovered in Dartmoor, local archaeologists are thrilled by the unusual find. But when the body is identified as a cold case murder victim, detectives must unravel a murky web of forbidden love and family tragedy as they attempt to uncover the truth.

Available on Amazon.

Carryl Church’s debut novel The Forgotten Life of Connie Harris came out in September published by Joffe books. It’s a dual timeline historical romance set in Tiverton and Exeter in the 1950s and 1990s against the backdrop of cinema.

Carryl Church’s debut novel The Forgotten Life of Connie Harris came out in September published by Joffe books. It’s a dual timeline historical romance set in Tiverton and Exeter in the 1950s and 1990s against the backdrop of cinema.

Available on Amazon.

Lock, Stock and Harold is a new novel by Ebberley Finch. When you decide to change your life, expect the unexpected. . . After a crushing break-up, Noah Wood ends up with no home, no job and no direction. With a wish-list in mind, he moves to the beautiful Devon coast, hoping to rebuild his shattered confidence. Inspired by his uncle, he buys an abandoned pet shop ‘Lock, Stock and Barrel’, only to find an unexpected item in the bagging area – a parrot called Harold. This charming tale is full of captivating characters and humorous moments. Perfect for readers who enjoy Matt Haig, Nick Hornby, Ruth Hogan and Sally Page. Available on Amazon.

Lock, Stock and Harold is a new novel by Ebberley Finch. When you decide to change your life, expect the unexpected. . . After a crushing break-up, Noah Wood ends up with no home, no job and no direction. With a wish-list in mind, he moves to the beautiful Devon coast, hoping to rebuild his shattered confidence. Inspired by his uncle, he buys an abandoned pet shop ‘Lock, Stock and Barrel’, only to find an unexpected item in the bagging area – a parrot called Harold. This charming tale is full of captivating characters and humorous moments. Perfect for readers who enjoy Matt Haig, Nick Hornby, Ruth Hogan and Sally Page. Available on Amazon.

[image error]Protected by a forbidding security fence between the moor and the town lies a farm …

The Reporter is a mystery set on Dartmoor. Rachel Francis has worked as a pony trek leader and on a hill farm. She is interested in rural and indigenous cultures and where they overlap.

https://www.long-acre-rfrancis.com/

Here’s an offer that’s a bit off the wall (or off the shelf…). Laura Harrison McBride has a free copy of her cozy mystery Christmas shelf barker novelette to give away to the first person who emails in the correct definition of the term ‘shelf barker’. Email your answer to pu*******@mu************.com. Good luck!

We mentioned last month that Angela Joyce’s first novel The Rydle Year comes out in February. It’s a nostalgic tale set in 1970s Plymouth. Angela has let us know that the book launch party will be on 26 March at Ocean Studios Plymouth. Contact Angela if you want to attend.

Helena Dixon is delighted to announce that Murder at the Beauty Pageant, her cozy mystery where amateur sleuth Kitty Underhay investigates the murder of a contestant at a glamorous beauty pageant, is on the New York Post list of thirteen best cozy mysteries. It’s the twelfth of eighteen Kitty Underhay mysteries, and if the New York Post is any judge, well worth checking out!

Helena Dixon is delighted to announce that Murder at the Beauty Pageant, her cozy mystery where amateur sleuth Kitty Underhay investigates the murder of a contestant at a glamorous beauty pageant, is on the New York Post list of thirteen best cozy mysteries. It’s the twelfth of eighteen Kitty Underhay mysteries, and if the New York Post is any judge, well worth checking out!

Di Castle’s memoir of growing up in the 1950s and 1960s in Harpenden is out now. Red House to Exodus, while set in Hertfordshire, has themes which will resonate with all baby boomers and others.

Di Castle’s memoir of growing up in the 1950s and 1960s in Harpenden is out now. Red House to Exodus, while set in Hertfordshire, has themes which will resonate with all baby boomers and others.

Available on Amazon.

Sharon Francis’s latest rom com book, A Reason To Be, was released last week and is the third in her Limbo series. Available on Amazon.

Sharon Francis’s latest rom com book, A Reason To Be, was released last week and is the third in her Limbo series. Available on Amazon.

The Barmouth Affairs by Vanessa M. Tanner launched earlier this month, and went as high as no. 31 in Women’s Popular Fiction on Amazon. This heartwarming, nostalgic and atmospheric story of life, love, and two women’s search for happiness is set in the 1970s, and is based on true events.

The Barmouth Affairs by Vanessa M. Tanner launched earlier this month, and went as high as no. 31 in Women’s Popular Fiction on Amazon. This heartwarming, nostalgic and atmospheric story of life, love, and two women’s search for happiness is set in the 1970s, and is based on true events.

Available on Amazon.

The post The Thursday Book Club – Dec 24 appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

November 23, 2024

The Thursday Book Club – Nov 24

The latest edition of The Thursday Book Club was broadcast on 21st November 2024 at 2pm on Phonic FM. Joining host Jonathan Posner was Jason Mann. Click the names to find out more about them, and use the audio bar below to listen to the full show.

The latest edition of The Thursday Book Club was broadcast on 21st November 2024 at 2pm on Phonic FM. Joining host Jonathan Posner was Jason Mann. Click the names to find out more about them, and use the audio bar below to listen to the full show.

We reviewed The Winter Guest by W. C. Ryan.

Our discussion was on: What makes a good historical novel??

The next show is at 2pm on the 19th December 2024. We’ll be reviewing Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan. Read along with us and send us your thoughts on the book – either through the Contact page, or via the Facebook page, and we may well read them out on air.

NEWS  For All Your Endeavours by David Sharp is a captivating tale of murder in the most unexpected of places. When a ‘bog body’ is discovered in Dartmoor, local archaeologists are thrilled by the unusual find. But when the body is identified as a cold case murder victim, detectives must unravel a murky web of forbidden love and family tragedy as they attempt to uncover the truth.

For All Your Endeavours by David Sharp is a captivating tale of murder in the most unexpected of places. When a ‘bog body’ is discovered in Dartmoor, local archaeologists are thrilled by the unusual find. But when the body is identified as a cold case murder victim, detectives must unravel a murky web of forbidden love and family tragedy as they attempt to uncover the truth.

Carryl Church’s debut novel The Forgotten Life of Connie Harris came out in September published by Joffe books. It’s a dual timeline historical romance set in Tiverton and Exeter in the 1950s and 1990s against the backdrop of cinema.

Carryl Church’s debut novel The Forgotten Life of Connie Harris came out in September published by Joffe books. It’s a dual timeline historical romance set in Tiverton and Exeter in the 1950s and 1990s against the backdrop of cinema.

Jenny Bradley’s book Tidelines, A Year of the Coast, will be published on November 29th by Clevedon Community Press. It’s a collection of poetry and prose about the coast set over a calendar year. Started in lockdown, it aims to share the joy and comfort nature can bring, along with raising awareness of our beautiful, fragile coastline. Jenny says she is passionate about writing and protecting the environment, and this book combines both. Jenny hopes others find beauty and hope in the pictures she paints with words. It will be available from the Clevedon Community Bookshop in North Somerset.

Gary Miles’s new book was published at the end of last month. Called Where The Mind Wanders, it’s a tale of dreamers, druids and queens. It’s available from Amazon and most online retailers in paperback and ebook. It could be the ideal gift for a teenager, or an adult who likes fantasy.

Gary Miles’s new book was published at the end of last month. Called Where The Mind Wanders, it’s a tale of dreamers, druids and queens. It’s available from Amazon and most online retailers in paperback and ebook. It could be the ideal gift for a teenager, or an adult who likes fantasy.

The follow up to the debut novel The Pool by Richard Collis will be released in a month’s time, just in time for Christmas. The new book is called Wolf Mother, and explores themes of motherhood, nature and chaos.

The follow up to the debut novel The Pool by Richard Collis will be released in a month’s time, just in time for Christmas. The new book is called Wolf Mother, and explores themes of motherhood, nature and chaos.

The 20th novel from Terri Nixon comes out on 5th December. It’s the final book in her latest Cornish saga, Pencarrack, and it’s called The Watchers of Pencarrack Moor. It’s set against the 1932 Dartmoor Prison Mutiny. Available on Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

The 20th novel from Terri Nixon comes out on 5th December. It’s the final book in her latest Cornish saga, Pencarrack, and it’s called The Watchers of Pencarrack Moor. It’s set against the 1932 Dartmoor Prison Mutiny. Available on Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Orlando Murrin’s debut crime novel, Knife Skills For Beginners is a whodunit set in a posh London cookery school. It’s been shortlisted for the Crime Fiction Lovers Debut Award 2024, and it’s decided by public vote. So if anyone has read it and liked it, or just wants to do Orlando a favour, go to www.crimefictionlover.com and vote (takes 15 seconds). We’ll put the link up on the Listen Again page. The book was also shortlisted for the McDermid Debut Award.

Orlando Murrin’s debut crime novel, Knife Skills For Beginners is a whodunit set in a posh London cookery school. It’s been shortlisted for the Crime Fiction Lovers Debut Award 2024, and it’s decided by public vote. So if anyone has read it and liked it, or just wants to do Orlando a favour, go to www.crimefictionlover.com and vote (takes 15 seconds). We’ll put the link up on the Listen Again page. The book was also shortlisted for the McDermid Debut Award.

Tinsel and Tapas, Paula Rooney’s third travel memoir, came out last week. It’s all about her solo month’s trip around Andalucia, Spain, searching for Christmas. Her children have flown the nest and she says Christmas has lost its sparkle without them. In a bold move, Paula decided to forgo an English Christmas altogether and embarked on a solo adventure to explore the warmth and beauty of Andalusia, Spain. The perfect book for readers searching for a story about reclaiming joy and embracing life’s unexpected turns, this heartfelt memoir will remind you that new beginnings can happen at any age, and that sometimes the best gift we can give ourselves is the courage to change.

Tinsel and Tapas, Paula Rooney’s third travel memoir, came out last week. It’s all about her solo month’s trip around Andalucia, Spain, searching for Christmas. Her children have flown the nest and she says Christmas has lost its sparkle without them. In a bold move, Paula decided to forgo an English Christmas altogether and embarked on a solo adventure to explore the warmth and beauty of Andalusia, Spain. The perfect book for readers searching for a story about reclaiming joy and embracing life’s unexpected turns, this heartfelt memoir will remind you that new beginnings can happen at any age, and that sometimes the best gift we can give ourselves is the courage to change.

James Lee’s 2nd book will be out in December. It’s called Sleeping in the Ditch with Slobodan Milosevic. James says he’s bringing peace to the Former Yugoslavia with diesel, gas, plastic cutlery and booze. For James, 1996 was the time of his first tour of the Balkans, capturing the surreal situations in which he often found himself, where the line between the absurd and the tragic was constantly blurred. It’s a tribute to all who took part in encouraging peace in the Balkans after one of modern Europe’s darkest periods. James’s first book Licking The Taliban’s Flip-Flop, is on Amazon, so it’s fairly safe to assume this one will be as well.

James Lee’s 2nd book will be out in December. It’s called Sleeping in the Ditch with Slobodan Milosevic. James says he’s bringing peace to the Former Yugoslavia with diesel, gas, plastic cutlery and booze. For James, 1996 was the time of his first tour of the Balkans, capturing the surreal situations in which he often found himself, where the line between the absurd and the tragic was constantly blurred. It’s a tribute to all who took part in encouraging peace in the Balkans after one of modern Europe’s darkest periods. James’s first book Licking The Taliban’s Flip-Flop, is on Amazon, so it’s fairly safe to assume this one will be as well.

Clive Donovan’s third book of poetry Movement of People is available in all good book shops or from the publishers, Dempsey & Windle. According to their website, it’s an ambitious portrayal of the world — as seen in a timeless mirror — of its problems and betrayals. The causes and effects of mass-migrations, climate change, war, genocide and man’s inhumanity to man are explored in striking, powerful poems. Clive Donovan’s uncompromising vision is tempered by his wry sense of humour — a virtuoso writer, he confidently ranges through time and place to present vivid evidence for his principles, always thought-provoking, never didactic.

Clive Donovan’s third book of poetry Movement of People is available in all good book shops or from the publishers, Dempsey & Windle. According to their website, it’s an ambitious portrayal of the world — as seen in a timeless mirror — of its problems and betrayals. The causes and effects of mass-migrations, climate change, war, genocide and man’s inhumanity to man are explored in striking, powerful poems. Clive Donovan’s uncompromising vision is tempered by his wry sense of humour — a virtuoso writer, he confidently ranges through time and place to present vivid evidence for his principles, always thought-provoking, never didactic.

Project Deadhead by local author Bob Fairbrother has just been launched, and he says he’s currently busy on the road promoting. This dystopian near future thriller features DCI MacGillivray solving murders as the UK economy teeters on the edge of collapse, heralding a bleak era of lawlessness. Available on Amazon.

Project Deadhead by local author Bob Fairbrother has just been launched, and he says he’s currently busy on the road promoting. This dystopian near future thriller features DCI MacGillivray solving murders as the UK economy teeters on the edge of collapse, heralding a bleak era of lawlessness. Available on Amazon.

Helena Dixon’s new book, Murder in New York releases November 25th. Available in kindle, paperback and audio and free to read on kindle unlimited. It’s Kitty Underhay’s 18th mystery, and it’s set in 1936 in – you guessed it – New York. Perfect for fans of Agatha Christie, T.E. Kinsey or Lee Strauss, who will adore this utterly charming murder mystery. The perfect treat for cozy crime fans!

Helena Dixon’s new book, Murder in New York releases November 25th. Available in kindle, paperback and audio and free to read on kindle unlimited. It’s Kitty Underhay’s 18th mystery, and it’s set in 1936 in – you guessed it – New York. Perfect for fans of Agatha Christie, T.E. Kinsey or Lee Strauss, who will adore this utterly charming murder mystery. The perfect treat for cozy crime fans!

Alison Simpson is an author in Torbay who has recently switched genres from romance to cosy murder/mystery. The first in her new series, featuring super-sleuthing twins Kitty and Nora Markham in 1930s Torquay – is called Murder under the Rock. It’s due for publication in April 2025. Pre-readers are invited to sign up to Alison’s newsletter to get lots of interesting bookish news, competitions, free chapters and exclusive access. Sign up at www.alisimpson.co.uk.

Alison Simpson is an author in Torbay who has recently switched genres from romance to cosy murder/mystery. The first in her new series, featuring super-sleuthing twins Kitty and Nora Markham in 1930s Torquay – is called Murder under the Rock. It’s due for publication in April 2025. Pre-readers are invited to sign up to Alison’s newsletter to get lots of interesting bookish news, competitions, free chapters and exclusive access. Sign up at www.alisimpson.co.uk.

Laura Harrison McBride is an ex-journalist who has now retired after 45 years and has turned her hand to poetry. She has several books of poetry on Amazon, such as Time on a Greased Toboggan: Fear, hope and the whole enchilada. Her next volume of poems comes out in the early spring.

Laura Harrison McBride is an ex-journalist who has now retired after 45 years and has turned her hand to poetry. She has several books of poetry on Amazon, such as Time on a Greased Toboggan: Fear, hope and the whole enchilada. Her next volume of poems comes out in the early spring.

Talking of poetry, Songs from a Tone-Deaf Minstrel is coming out on November 26th, from author Jane Jago. This collection of poems, from love songs to limericks, is available to pre-order on Amazon.

Talking of poetry, Songs from a Tone-Deaf Minstrel is coming out on November 26th, from author Jane Jago. This collection of poems, from love songs to limericks, is available to pre-order on Amazon.

Debut author Angela Joyce’s first novel The Rydle Year comes out in February. It’s a nostalgic tale set in 1970s Plymouth.

The Barmouth Affairs by Vanessa M. Tanner is available to pre-order on Amazon. This is a heartwarming, nostalgic and atmospheric story of life, love, and two women’s search for happiness. It’s also set in the 1970s, and is based on true events.

The Barmouth Affairs by Vanessa M. Tanner is available to pre-order on Amazon. This is a heartwarming, nostalgic and atmospheric story of life, love, and two women’s search for happiness. It’s also set in the 1970s, and is based on true events.

The post The Thursday Book Club – Nov 24 appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

October 20, 2024

Tudor era play – review

I went to the Northcott Theatre in Exeter this weekend, to see the world premiere of a play called The Commotion Time. It’s set in Poundstock in North Cornwall in my favourite Tudor period, and although the action of the play takes place in the hamlet, there is a strong influence from Exeter as the administrative centre for the region.

“It’s February 1547, soon after the death of Henry VIII. On the Cornwall/Devon border, the people of Poundstock are looking forward to completing their biggest ever community project: the Gildhouse, a state-of-the-art building for brewing, fundraising and feasting. But there are dangerous clouds on the horizon as the authorities in Exeter force through an array of reforms set to drive division into the heart of the community.

As bellies empty, society fractures and the Gildhouse’s key is taken away, the people take action in the only way left to them; marching to Exeter in their thousands to challenge the king and finally be heard.”

Quote taken from the Northcott Theatre website.

The production featured seven professional actors, and a massive cast of local amateurs.

The professionals were excellent, and the local cast also performed well, making all the right moves and mutterings as and when required, but it was their singing that really stood out – uplifting and beautiful. The story was well told, and generally easy to follow, although I would have preferred if the writer hadn’t tried to be so accurate to the language of the day. It’s a point I have made myself in other posts – if you try to be too accurate in historical language, it can make the listener (or in my case, the reader) sometimes struggle to understand what is being said. Here, the consistent use of the word ‘us’ instead of ‘we’ became a tad irksome (although I did spot some uses of ‘we’ creeping in occasionally – I couldn’t decide if it was deliberate or an oversight…)

Apart from the occasional anachronistic costume faux-pas, I really enjoyed being immersed in the Tudor world for a few hours. One of the main themes of the piece was the upheaval for the ordinary people caused by the religious changes from Catholic to Protestant – also something I have blogged about. It’s hard to underestimate how disruptive it must have been for them, and the play brought this out well. No wonder they marched on Exeter, in a (doomed) attempt to reverse the changes.

The post Tudor era play – review appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

Cosy crime series set in Devon

I was delighted to attend an interview and reading by Devon author Stephanie Austin at the weekend.

The venue was ideal – the atmospheric Old Exeter Inn in the ancient stannary town of Ashburton, which dates back to the 12th century (the Inn, not Ashburton, – which I am assuming is older). Apparently the Old Exeter was where Sir Walter Raleigh was arrested on 19 July 1603.

Stephanie introduced us to her work – a series of compelling cosy mysteries set in and around Ashburton, featuring amateur sleuth Juno Browne.

Stephanie introduced us to her work – a series of compelling cosy mysteries set in and around Ashburton, featuring amateur sleuth Juno Browne.

Stephanie’s books are published by Allison & Busby, and sound excellent. I already have my nose buried in her first book, Dead in Devon.

Stephanie’s books are available on Amazon – put this code into your Amazon search bar: B07MTSDFJG.

The post Cosy crime series set in Devon appeared first on Jonathan Posner.

Firebrand movie; worth the wait?

It took a while but I finally got to see Firebrand, the movie about Katherine Parr; sixth wife of Henry VIII.

Overall I enjoyed it. But did it live up to my expectations? Yes and no.

The bad:

• Too many clichés

– Bunch of Tudors riding across a modern-looking open field

– Revellers performing and dancing in front of bored king on throne

– Tudor court = political intrigue

• Too much messing about with known history – and missing out on the real dramatic scene of how Katherine managed to turn Henry back onto her side, and how he then gave Gardner his come-uppance (a scene I was waiting for and never got). Instead we got two ‘unhistorical’ plot devices – neither of which actually happened (I won’t spoil it for you by saying what they were. You’ll know…)

• Poor editing – it was as if the editor got bored with a scene and cut away just as something interesting was about to happen

• What happened to the Thomas Seymour relationship? He was the love of her life; here they just seem to be quite good friends

– I wasn’t sure about the girl playing Princess Mary – given how well Elizabeth was cast, I felt Mary looked nothing her portraits.

But there was also much to like:

• Casting and acting was good

– Particularly Jude Law, very believable as the vile king with the stinky leg, and playing very much against type

– Alicia Vikander was good, but a bit vanilla at times – she could have played Katherine as a bit more forceful

– The girl playing Elizabeth looked exactly as one would expect the young Elizabeth to look

– Erin Doherty as Anne Askew was very good – she does a good line in strong, quirky women (she was Princess Anne in The Crown)

– They made a brave attempt at the weird beards we see in the portraits (particularly the Seymour brothers), although they could have been applied a bit more realistically

• The atmosphere and lighting felt period-correct – not over-lit

• The stinky leg was well played – apparently the king could be smelled from half way across a large building.

Probably not one to buy on DVD but to watch occasionally on streaming or terrestrial if it comes on in future.

Image is copyright of its owner – all rights respected.

The post Firebrand movie; worth the wait? appeared first on Jonathan Posner.