Jennifer Hallock's Blog: Sugar Sun Series Extras, page 3

February 8, 2021

Loosening Up in 1910

Though not the height of fashion, a white cotton shirtwaist was the unofficial uniform of schoolteachers in the Edwardian Philippines. Having used a chalkboard for a good part of my own teaching career, I can attest that having your sleeves already be white is extremely practical. Two of my previous heroines, Georgina and Allegra, thought so too.

Miss Laura Reed, an American schoolteacher, or Thomasite, in her shirtwaist and skirt at Calasiao, Pangasinan, north of Manila. Photo courtesy of the Philippine Photographs Digital Archive, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

Miss Laura Reed, an American schoolteacher, or Thomasite, in her shirtwaist and skirt at Calasiao, Pangasinan, north of Manila. Photo courtesy of the Philippine Photographs Digital Archive, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.According to the Indianapolis Journal on January 1, 1900: “The shirtwaist will be with us more than ever this summer. Women are wearing shirtwaists because they are comfortable, because they can be made to fit any form, and because they are mannish.” Fashion historian Catherine Gourley explains that “it was similar to a man’s shirt. It had a stiff, high-necked collar and buttons down the front. Women often wore one with a floppy bow or tie. Some pinned a brooch to the collar.”

In contrast, high fashion in the first decade of the 1900s was a structured Gibson Girl silhouette that looked a lot like that of the previous century, particularly the painfully small waist. The badly named “health” corset “pushed the bust forward and the hips back in an attempt to avoid pressure on the abdomen,” according to the timeline of the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) of the State University of New York. The shape was top-heavy with dramatic sleeves, “enhanced with petticoats that had full backs and smooth fronts” (FIT).

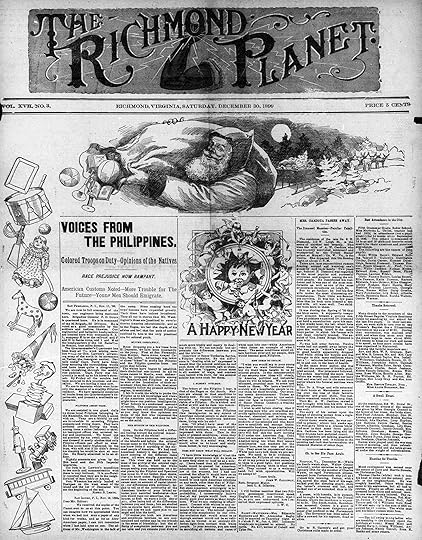

Sugar Communion’s heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd, as inspired by an 1896 fashion plate at the Met. (She will borrow the dress.)

Sugar Communion’s heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd, as inspired by an 1896 fashion plate at the Met. (She will borrow the dress.)Dresses did not loosen until around 1910 or so, but fortunately Sugar Communion is quite epic in scope so I can explore new fashion templates that look far more comfortable. I was surprised by how 1920s-esque they looked, and then I found that FIT agreed with me: “While changes in women’s fashion that manifested in the 1920s are often attributed to changes due to World War I, many of the popular styles of the twenties actually evolved from styles popular before the war and as early as the beginning of the decade.”

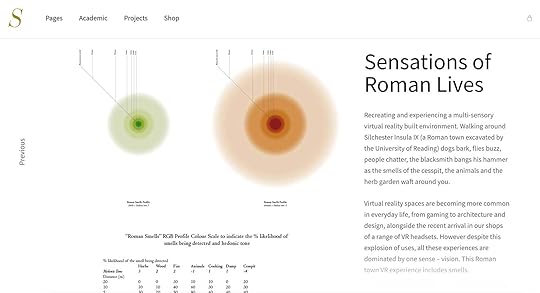

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 105, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 105, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.I paged through only a few of the plates at the Costume Institute Collections at The Met to get an idea of what I would like to see Liddy wear, when she gets the chance—when she is not tending to patients in a practical shirtwaist, that is.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 118, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 118, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.I think the geometric patterns on the above skirt would appeal, though Liddy is not likely to be seen at entertainments like horse races, nor would she approve, probably.

Costume Institute Fashion Plates 119 and 127, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Costume Institute Fashion Plates 119 and 127, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.See what I mean by the roaring twenties vibe? Ignore the hat on the right, which seems to be an inspiration for Dr. Seuss’s cat. Both of these dresses seem so elegant. The one on the left I can see Miss Fisher wearing while she solves a murder mystery.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 113, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 113, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.I do not understand the knotted kerchief hanging off the belt on the right illustration above, but that blouse and skirt is otherwise very modern. Also, women began to dare to show some ankle—racy, I know!—though not bare skin. My heroine Liddy does not have the time nor inclination for hose, so socks and boots are her daily wear.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 137, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 137, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.I think that back in the 1980s I had a blouse like the one above on the left. No feathered hats for me or Liddy, though.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 133, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Costume Institute Fashion Plate 133, 1910-1913, at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.These plates tell me that clothing was starting to become more comfortable, and even high fashion followers did not want to be dependent on a maid to dress them all the time.

Can you imagine having a ladies’ valet in 2020? “The yoga pants again, ma’am?”

February 6, 2021

A Victorian-esque Baby Shower Toast

About a year ago I co-hosted a baby shower for two friends, one of whom teaches history with me. To guard their privacy, I will rename the couple Leo and Julia Sterling, partly based on yesterday’s and today’s names of the day at , one of my favorite character development tools. The fake surname came from a new tool that I will have to add to my list: the .

Because this speech fits into my recent dive into nineteenth-century medicine, sex education, and medical history in general, I thought that I would publish it here.

Read more about why cocaine for surgery and heroin from the Sears Catalog was actually a step up for the history of medicine.Victorian childbirth and child-rearing: A Toast

Read more about why cocaine for surgery and heroin from the Sears Catalog was actually a step up for the history of medicine.Victorian childbirth and child-rearing: A ToastIn the division of labor that produced this shower, my fellow co-hosts chose me to say a few words because of my extensive experience in childbirth and child-rearing. [Ahem, no.]

I thought that I would start with a language Leo and I both understand: history. I sought advice from Victorian England, which as we all know is really the apex of inclusivity, equality, and morality. [More laughter because, yes, this is ridiculously untrue.]

I first took a look through Letters to a Mother, on the Management of Herself and her Children in Health and Disease, Embracing the Subjects of Pregnancy, Childbirth, Nursing, Food, Exercise, Bathing, Clothing, etc. etc. with Remarks on Chloroform. The chloroform was for the mother, not the child, to help her remain “in a state of quiet, placid slumber” throughout birth, just like Queen Victoria. That sounds awesome. Dangerous, maybe, but awesome. [Edited later: According to her physician, “The chloroform was not at any time carried to the extent of quite removing consciousness.” So less dangerous, but probably still awesome.]

Various bottles of chloroform dating from 1801 to 1910, courtesy of Wellcome Images at Wikimedia Commons.

Various bottles of chloroform dating from 1801 to 1910, courtesy of Wellcome Images at Wikimedia Commons.This book also warns us not to make the baby’s room in the basement of the house, so—Leo? Julia?—I think we’re good there. In other research, the Boston Medical Journal does warn of the “intemperate use of fruit,” and I am not sure what to tell you to do with that piece of information.

Master Baby by Sir William Quiller Orchardson, painted in 1886 and now housed in the Scottish National Gallery. Digital image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Master Baby by Sir William Quiller Orchardson, painted in 1886 and now housed in the Scottish National Gallery. Digital image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Woman’s Worth; or, Hints to Raise the Female Character is maybe a better fit for us, especially for Julia’s interests. It seems to know of her love of “the blandishments of the theatre [and] the excitements of the dance,” and it mentions the option of committing “the charge of her child to dependents and servants” so that she preserve time for all her interests. This sounds good to me, as well; but in the same pages, the book advises that a parent’s influence is essential in the child’s character development. For no matter the “attractiveness of children, there are in those young hearts the seeds of evil,” including “dark deformity, headstrong passions, and vicious thoughts.” I think all of the educators in this room are nodding their heads.

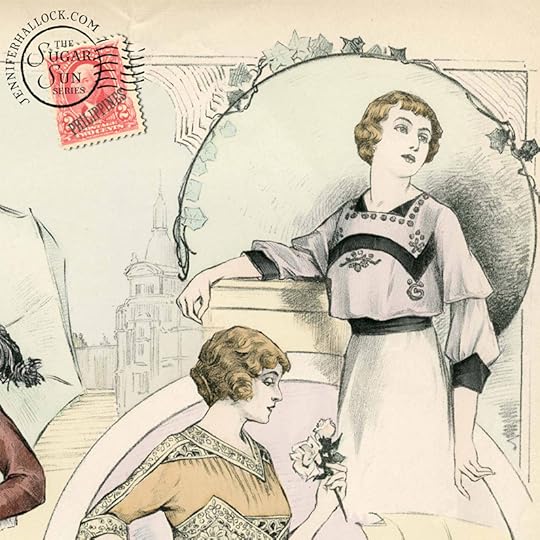

Is proper education the answer, you wonder? The Rearing and Training of Children cautions that reading “is generally begun too early,” so maybe you will just have to throw away all those children’s books you’ve received, including the ones from us.

This is the cover of the 1902 first edition of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, which currently makes an appearance in my WIP, Sugar Communion. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. For a more updated read, I can tell you that the Hallocks’ favorite gift books to give are: The Monster at the End of This Book, Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, and The Story of Ferdinand.

This is the cover of the 1902 first edition of The Tale of Peter Rabbit, which currently makes an appearance in my WIP, Sugar Communion. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. For a more updated read, I can tell you that the Hallocks’ favorite gift books to give are: The Monster at the End of This Book, Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, and The Story of Ferdinand.The manual continues: “As for committing prose or verse to memory, the practice, good enough in some respects, is much abused. Children will remember what they know and feel interested in, and knowledge should come to them easily, sweetly, and naturally.” Leo, I think your students would like you to pay particular attention to this point. There is “no necessity for any part of education being made irksome.”

Tell that to this American Thomasite, Mary Scott Cole, who is pictured with her class in Palo, Leyte. Photo from the University of Michigan Bentley History Library.

Tell that to this American Thomasite, Mary Scott Cole, who is pictured with her class in Palo, Leyte. Photo from the University of Michigan Bentley History Library.But, frankly, I don’t think any of these manuals are helpful to us. History has failed me. What else can I draw upon? Well, I have raised three dogs from puppies, and I treat them all like my children. In that case, I cannot stress enough the importance of crate-training. The general rule of thumb is that your new furry bundle of joy can be left in his crate about an hour at a time for each month of age. Also, freeze-dried liver and pigs’ ears are particularly effective training treats and sure to be your baby’s favorite, especially if we are to avoid that nefarious fruit.

Wait, has none of this been helpful?

Okay, well then let me say what we all know: Baby Sterling will be raised by two amazing parents. It has won the womb lottery. There is a reason that so many of us are here, that we seek Julia and Leo out in the Dining Hall or at faculty functions (and, yes, Leo, it is not just Julia we look for but you too). We are honored to be by your side as you start this new stage of your life. Know that there are many people in this room from whom you can seek support, comfort, and company. I just wouldn’t recommend asking your department head for advice.

Featured image: Bottles of Chloroform photographed and shared in the Creative Commons by Kevin King, via Wikimedia Commons.Bibliography

Featured image: Bottles of Chloroform photographed and shared in the Creative Commons by Kevin King, via Wikimedia Commons.BibliographyBrown, William C., ed. The Mother’s Assistant and Young Lady’s Friend. Boston: David H. Els, 1841. Accessed August 23, 2019. http://books.google.com/books?id=65NQAQAAMAAJ.

Caton, Donald. What a Blessing She Had Chloroform: The Medical and Social

Response to the Pain of Childbirth from 1800 to the Present. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999. EBSCO eBook Collection (53042).

Conquest, J. T., M.D., F.L.S. Letters to a Mother, on the Management of Herself and her Children in Health and Disease, Embracing the Subjects of Pregnancy, Childbirth, Nursing, Food, Exercise, Bathing, Clothing, etc. etc. with Remarks on Chloroform. London: Longman and Co., 1848. Accessed September 15, 2019. http://books.google.com/books?id=ACdlAAAAcAAJ.

The Metropolitan Working Classes’ Association for the Betterment of Public Health. The Rearing and Training of Children. London: John Churchill, 1847. Accessed September 15, 2019. http://books.google.com/books?id=o_MDAAAAQAAJ.

Woman’s Worth; or, Hints to Raise the Female Character. London: H.G. Clarke & Co., 1844. Accessed September 15, 2019. http://books.google.com/books?id=vmtjAAAAcAAJ.

January 17, 2021

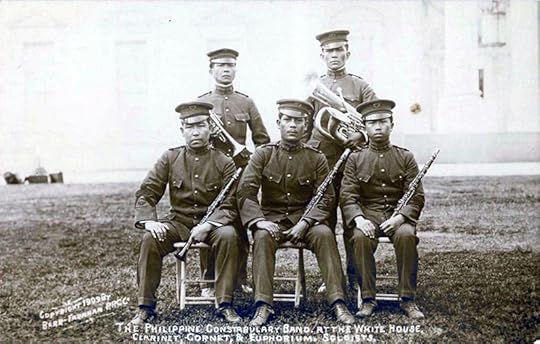

Sergeant Major John W. Calloway: A Voice to Challenge Empire

In November of 1899 the Philippine-American War shifted into a long stage of protracted guerrilla warfare. Outnumbered by the uniformed Filipino revolutionaries by more than three to one, and with white volunteer regiments rotating home at the end of their year-long enlistments, the War Department transferred 6000 African American soldiers to the Philippines (Russell 2014, 205). This included the 24th and 25th Infantries to the Philippines, as well as two newly-formed regiments (the 48th and 49th US Volunteer Infantries), and both the 9th and 10th Cavalries (New York State Division).

There was good reason to call upon them: many of these men had achieved the highest military honors in the land due to their courage and valor under fire. The new arrivals “built and maintained telegraph lines, constantly performed patrol and scouting duties, provided protection for work crews constructing roads, escorted supply trains, and located and destroyed insurgent ordnance and other supplies” (Russell 2014, 205-6). But there would be a cost for doing their jobs too well. Sergeant Major John W. Calloway, experienced soldier and reporter for the Richmond Planet, called out the incongruency between empire and democracy—in private correspondence—and he was punished for it.

“Dress on the Colors” by Dale Gallon. Acting Color Sergeant George Berry of Troop G, 10th US Cavalry Regiment carries the national flag of his own command as well as the standard of the 3rd US Cavalry Regiment in the assault upon the Spanish works at Kettle Hill, San Juan Heights, Cuba, July 1, 1898. Original commissioned by US Army War College, Carlisle, PA.relations with the Filipino public

“Dress on the Colors” by Dale Gallon. Acting Color Sergeant George Berry of Troop G, 10th US Cavalry Regiment carries the national flag of his own command as well as the standard of the 3rd US Cavalry Regiment in the assault upon the Spanish works at Kettle Hill, San Juan Heights, Cuba, July 1, 1898. Original commissioned by US Army War College, Carlisle, PA.relations with the Filipino publicIn November 1899, while the 25th Infantry was operating in the north of the country, they planned the raid of an enemy stronghold. In a war where “marked severities” were common enough among white units to warrant a later Senate investigation, the 25th kept their discipline. “In an instance of impressive restraint, these African American soldiers refused to massacre the unprepared and unorganized Filipino troops; instead they took over a hundred prisoners and captured stores of food, ammunition, and weapons” (Russell 2014, 205-6).

Formation of Black soldiers, after the Spanish-American War. Accessed at the Library of Congress.

Formation of Black soldiers, after the Spanish-American War. Accessed at the Library of Congress.Filipino citizens immediately noticed the difference. As Filipino physician Torderica Santos told Sgt. Maj. Calloway:

Of course, at first we were a little shy of you [Black soldiers], after being told [by the whites] of the difference between you and them; but we studied you, as results were shown. Between you and him, we look upon you as the angel and him the devil. Of course you both are American, and conditions between us are constrained, and neither can be our friends in the sense of friendship; but the affinity of complexion between you and me tells, and you execute your duty so much more kindly and manly in dealing with us. We can not help but appreciate the difference between you and the whites (“Voices from the Philippines” 1899, 1).

In the article in the Planet, Calloway explains what passes as treating Filipinos kindly, at least by American Army standards: not spitting at them in the streets or calling them racial epithets (“Voices from the Philippines” 1899, 1).

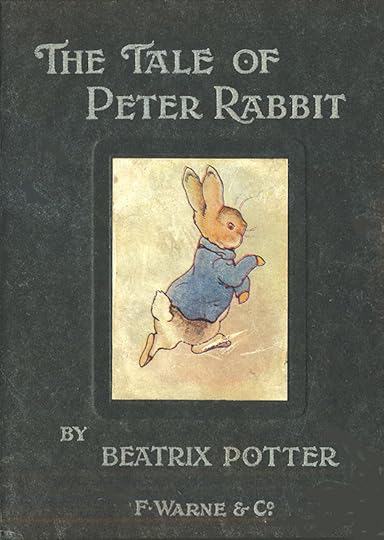

“Voices from the Philippines,” written by Sergeant Major John W. Calloway, and printed in the Richmond Planet on 30 December 1899. Full text courtesy of the US Library of Congress Chronicling America project.

“Voices from the Philippines,” written by Sergeant Major John W. Calloway, and printed in the Richmond Planet on 30 December 1899. Full text courtesy of the US Library of Congress Chronicling America project.Because of this relatively sympathetic treatment, some Filipinos were eager to have all American officials in their country be African Americans. “I wish you would say to your young men that we want Occidental ideas, but we want them taught to us by colored people. . . . We ask your educated, practical men to come and teach us them,” said wealthy planter Tomas Consunji, from San Fernando, Pampanga, north of Manila (“Voices from the Philippines,” 1).

Calloway agreed. He finished the article thus:

I wish to add before closing, that if our young men who are practical scientific agriculturalists, architects, mechanical, electrical and mining engineers, business men, professors and students of the sciences and who know how to establish and manage banks, mercantile business, large plantations, sugar growing, developing and refining, they will find this the most inviting field under the American flag. Cuba does not compare with the Philippines. Another thing too when they secure missionaries and teachers for the schools here, see that they get on the list. They must be represented there. . . . They extend to us a welcome hand, full with opportunities. Will we accept it? (“Voices from the Philippines,” 1).

Notice that in Calloway’s printed work, he agreed with the Progressives in their nation-building programs of “benevolent assimilation.” At least, he supported programs that provided opportunities for carpetbaggers of every race. A letter by Captain F. H. Crumbley of the 48th Volunteers printed in the Savannah Tribune agreed: “There are every openings here for the Negro in business, and room for thousands of them” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 49).

24th Infantry Leaving Salt Lake City, Utah, for Chattanooga, Tennessee, April 24th, 1898. Accessed at the Library of Congress.

24th Infantry Leaving Salt Lake City, Utah, for Chattanooga, Tennessee, April 24th, 1898. Accessed at the Library of Congress.Many Black soldiers did stay behind in the Philippines, according to another letter by Sergeant Major T. Clay Smith of the 24th Infantry in the Savannah Tribune: “ . . . several of our young men are now in business in the Philippines and are doing nicely, indeed, along such lines as express men, hotels and restaurants, numerous clerks in the civil government as well as in the division quartermaster’s office, and there are several school teachers, one lawyer, and one doctor of medicine” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 49). Others became agricultural tycoons, judges, or small business owners (Ontal 2002, 129).

There was room for romance too. “Arguably, the Philippine islands had in its possession history’s largest proportion of African-American soldiers who opted not to return home after completing military service abroad” (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 51). Over a thousand of the soldiers deployed in the Philippines married Filipino women and stayed in the islands (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 50). In fact, Governor Taft admitted that he feared that these soldiers got along “too well with the native women,” and so he sent the rest of the Black regiments Stateside as quickly as possible (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 50).

too much democracy? Or not enough.Got along too well? Exactly. In 1907 Stephen Bonsal, a Black correspondent in the Philippines wrote: “While white soldiers, unfortunately, got on badly with the natives, the black soldiers got on much too well. . . . the Negro soldiers were in closer sympathy with the aims of the native populations than they were with those of their white leaders and the policy of the United States” (quoted in Russell 2014, 213).

For example, Robert L. Campbell wrote to Booker T. Washington: “I believe these people are right and we are wrong and terribly wrong. I am in a position to keep from bearing arms against them and I will try and keep myself in such position until we are mustered out; of course, if I am ordered to fight, I will obey orders as a soldier should . . .” (quoted in Russell 2014, 212). But what if others did not obey orders?

The 24th U.S. Infantry at drill, Camp Walker, Philippine Islands, in or around 1902. If that date is accurate, Sgt. Maj. John Calloway had already been forced out of the Army. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The 24th U.S. Infantry at drill, Camp Walker, Philippine Islands, in or around 1902. If that date is accurate, Sgt. Maj. John Calloway had already been forced out of the Army. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.That was the worry when Sergeant Major Calloway’s case came to light. He had revealed a “dangerous” level of humanitarianism in private correspondence to his friend Tomas Consunji (Boehringer 2009, 3):

After my last conference with you and your father, I am constantly haunted by the feeling of what wrong morally we Americans are in the present affair with you. . . . Would to God it lay in my power to rectify the committed error and compensate the Filipino people for the wrong done! . . . The day will come when you [Filipinos] will be accorded your rights. The moral sensibilities of all America are not yet dead; there still smolders in the bosom of the country a spark of righteousness that will yet kindle into a flame that will awaken the country to its senses, and then! (Quoted in Russell 2014, 209).

In 1901, when white soldiers of the 3rd Infantry searched Consunji’s home for evidence of ties to nationalists, they found the correspondence between the two men. They sent it on to Calloway’s commanding officer, Colonel Henry B. Freeman of the 24th, a white man who had only been in the country for three months (Boehringer 2009, 2). Though Calloway claimed that the letters only expressed “a personal feeling, expressed to a personal friend, [and] had no other intent or motive,” the colonel believed them treasonous.

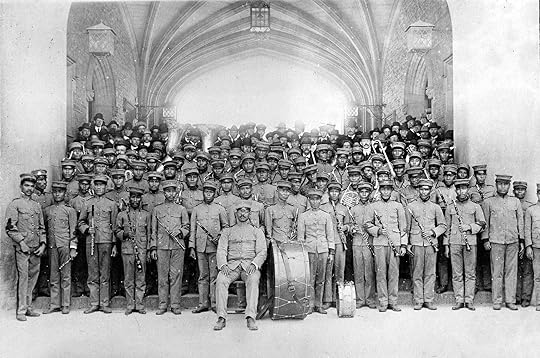

A group portrait of soldiers from the Company I, 24th Infantry Regiment, in uniform. Notice how many of the African American soldiers and NCOs are wearing medals for distinguished service: seven out of 44 pictured. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A group portrait of soldiers from the Company I, 24th Infantry Regiment, in uniform. Notice how many of the African American soldiers and NCOs are wearing medals for distinguished service: seven out of 44 pictured. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.Colonel Freeman wrote in the official report: “Battalion Sergeant Major Calloway is one of those half-baked mulattoes whose education has fostered his self-conceit to an abnormal degree” (quoted in Russell 2014, 213). If Calloway had an abundance of confidence, he had earned it through active service since 1892. He had done strike- and riot-breaking in the western mining states, along with hostage rescue, before fighting in three separate expeditions of the Cuban and Philippine fronts (Russell 2014, 215) and achieving the highest enlisted rank possible (Scot 1995, 166). Now, he wished to stay and invest his $1500 savings in a business venture in Manila, but he was thrown in Bilibid Prison instead. All this because of private correspondence, obtained by a possibly illegal search, that effectively said that imperialism was immoral—the very principle on which the United States of America was supposedly founded (Russell 2014, 212-13).

The 24th U.S. Infantry at drill, Camp Walker, Philippine Islands, about 1902. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The 24th U.S. Infantry at drill, Camp Walker, Philippine Islands, about 1902. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.In this and future American wars, one of the key tenets of counterinsurgency has been that military action alone will not encourage forces of resistance to set down their arms. People must see the carrot, not just feel the stick. In the Philippine-American War, the military leaders called this strategy “attraction.” Later, during another counterinsurgency in the Philippines, this time against communists during the 1950s, it was called “civic action.” In Vietnam, civilians colloquially called it “winning the hearts and minds” of the people. Good rapport, then, is an asset, not a liability. If African American regiments were forming true friendships with Filipinos, why were the white commanding officers so angry?

The Inspector-General would state: “I regard [Calloway] as a dangerous man, in view of his relations with the natives, as shown by this letter, and the circumstances of his court-martial” (Boehringer 2009, 3). Colonel Henry B. Freeman said of Sergeant Major John W. Calloway: “In my opinion he is likely to step into the Filipino ranks, should a favorable opportunity occur” (Russell 2014, 213). General Arthur MacArthur, commander of the entire war and father of future General Douglas MacArthur, agreed: “It is very apparent that [Calloway] is disloyal and should he remain in these islands, he would undoubtedly commit some act of open treason and perhaps join the insurrection out and out. One man of the 24th Infantry by the name of David Fagen has already done so and as a leader among the insurrectos is giving great trouble by directing guerrilla bands” (Boehringer 2009, 3).

There are no reliable photographs of David Fagen, either in the US or Philippine military. Most of the ones you see are actually different soldiers. This sketch from the 30 October 1900 issue of the Salt Lake Herald is not necessarily more reliable.

There are no reliable photographs of David Fagen, either in the US or Philippine military. Most of the ones you see are actually different soldiers. This sketch from the 30 October 1900 issue of the Salt Lake Herald is not necessarily more reliable.David Fagen’s story is worth a post of its own later, but this man was one of twenty-nine African American soldiers to desert the Army in the Philippines, and one of nine who defected to the Philippine Revolutionary Army (Robinson and Schubert, 73 n23). It is important to note that fourteen white soldiers also defected to the Filipino side (McCann and Lovell, 54), though that number was a smaller percentage of those who served in the islands. What particularly upset MacArthur about a Black soldiers’ defection was probably the phenomenon described by Ibram X. Kendi: “Negative behavior by any Black person became proof of what was wrong with Black people, while negative behavior by any White person only proved what was wrong with that person” (2017, 42-43).

Nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers,” African American units had been formed to fight in “government-led wars meant to overtake the Southwest and Great Plains from Native Americans.” The moniker “Buffalo Soldiers” may have been a compliment paid to the soldiers by the enemy, who noticed that the Black regiments “fought like the fierce Great Plains buffalo.” It also could have come from the buffalo robes that were not part of the official uniform but were procured by any soldier who could afford one, as shown in this Library of Congress photograph of soldiers of the 25th Infantry, at Ft. Keogh, Montana. Above quotations from Smithsonian Institute.

Nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers,” African American units had been formed to fight in “government-led wars meant to overtake the Southwest and Great Plains from Native Americans.” The moniker “Buffalo Soldiers” may have been a compliment paid to the soldiers by the enemy, who noticed that the Black regiments “fought like the fierce Great Plains buffalo.” It also could have come from the buffalo robes that were not part of the official uniform but were procured by any soldier who could afford one, as shown in this Library of Congress photograph of soldiers of the 25th Infantry, at Ft. Keogh, Montana. Above quotations from Smithsonian Institute.Black soldiers were specifically targeted by Filipino propaganda leaflets that brought up the same questions their own papers were asking back home (New York State Division). One read:

To the Colored American Soldier: It is without honor that you are spilling your costly blood. Your masters have thrown you into the most iniquitous fight with double purpose—to make you the instrument of their ambition and also your hard work will soon make the extinction of your race. Your friends, the Filipinos, give you this good warning. You must consider your history, and take charge that the Blood of Sam Hose proclaims vengeance (Ngozi-Brown 1997, 46).

This letter was attributed to President Emilio Aguinaldo, but many believe it was penned by Foreign Minister Apolinario Mabini (Ontal 2002, 125), the polymath genius who had studied American history and society closely enough to reference the horrific lynching and mutilation of Sam Hose of Newnan, Georgia. It was hard to ignore letters like Mabini’s. Even worse, it was hard not to notice how the new American regime was recreating the world of Sam Hose around them—and to wonder whether they, as soldiers in the US Army, were complicit in this expansion of segregation.

Racism and segregation in the military had clearly been at fault in causing Fagen’s defection. Fagen had been considered by his former white officers as “rowdy,” “bucking” his superiors, “a good for nothing whelp,” and “in continual trouble with the Commanding Officer” (Ontal 2002, 125). He had even been charged with seven counts of insubordination and punished with “all sorts of dirty jobs” (Ontal 2002, 125). After he defected, the colonial newspaper Manila Times depicted Fagen “as a gifted military tactician waylaying American patrols at will and then evading large forces sent in pursuit” (Ontal 2002, 126). He showed his former officers of the 24th Infantry exactly how wrong they were.

The fear of MacArthur and others was this: what if Calloway, the highest-ranking African American in the 24th, followed Fagen into the Philippine Revolutionary Army or any of the guerrilla organizations fighting in its name? Unlike Fagen, Calloway was already proven to be competent, highly-educated, and a fine leader. What damage could he do to the United States Army?

Charge of the 24th and 25th Infantry and rescue of Rough Riders at San Juan Hill, July 2nd, 1898. Illustration credited to Kurz & Allison, 1899, and accessed at Library of Congress.

Charge of the 24th and 25th Infantry and rescue of Rough Riders at San Juan Hill, July 2nd, 1898. Illustration credited to Kurz & Allison, 1899, and accessed at Library of Congress.But this fear was all in their heads! There was no evidence that Calloway ever considered defection. He hoped for both peace and Filipino rights, but he trusted in the people of the United States to provide both. The fact that the white officers understood Mabini’s propaganda to be effective means that they recognized the truth of it—which means that they should have seen that it was American policy to blame, not the sympathies of Calloway. Nevertheless, the Army busted Calloway down to private and dishonorably discharged him. He would try to reenlist several more times, the last during World War I, but he would be denied every time (Boehringer 2009, 3).

He was not the only one to be disappointed. What progress had been sought by the “Black Phalanx” was lost in the extension of Jim Crow policies throughout the empire (quoted in Gleijeses 1996, 188). The US military would not be desegregated until the Truman administration after World War II, when America’s role as the champion of democracy would be questioned by foreign allies (Kendi 2017, 351). The professionalism, excellence, and courage of African American soldiers in the 1898 wars has been largely forgotten in white-dominated histories of the period.

“Tramp, tramp, tramp for Cuba.” The 24th U.S. Infantry in Georgia in 1898, drilling for the upcoming war in Cuba. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.selected Bibliography:

“Tramp, tramp, tramp for Cuba.” The 24th U.S. Infantry in Georgia in 1898, drilling for the upcoming war in Cuba. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.selected Bibliography:[Featured image is a vintage postcard of the 25th Infantry at Basilan in the Sulu Archipelago.]

Boehringer, Gill H. “Imperialist (In)Justice: The Case of Sergeant Calloway.” Bulalat: Journalism for the People (Manila, Philippines), April 4, 2009. Accessed August 3, 2020. http://www.bulatlat.com/2009/04/04/imperialist-injustice-the-case-of-sergeant-calloway.

Brown, Scot. “White Backlash and the Aftermath of Fagen’s Rebellion: The Fates of Three African-American Soldiers in the Philippines, 1901-1902.” Contributions in Black Studies 13, no 5 (1995): 165-173. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol13/iss1/5.

Gleijeses, Piero. “African Americans and the War against Spain.” The North Carolina Historical Review 73, no. 2 (1996): 184-214. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23521538.

Kendi, Ibram X. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. New York: Bold Type Books, 2017. Kindle edition.

New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. “Black Americans in the US Military from the American Revolution to the Korean War: The Spanish American War and the Philippine Insurgency.” New York State Military History Museum and Veterans Research Center. Last modified March 30, 2006. Accessed June 29, 2020. http://dmna.ny.gov/historic/articles/blacksMilitary/BlacksMilitaryContents.htm.

Ngozi-Brown, Scot. “African-American Soldiers and Filipinos: Racial Imperialism, Jim Crow and Social Relations.” The Journal of Negro History 82, no. 1 (1997): 42-53. http://doi.org/10.2307/2717495.

Ontal, Rene G. “Fagen and Other Ghosts: African-Americans and the Philippine-American War.” In Vestiges of War: The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream, 1899-1999, edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis Francia, 118-30. New York: New York University Press, 2002.

Robinson, Michael C., and Frank N. Schubert. “David Fagen: An Afro-American Rebel in the Philippines, 1899-1901.” Pacific Historical Review 44, no. 1 (1975): 68-83. http://doi.org/10.2307/3637898.

Russell, Timothy D. “‘I Feel Sorry for These People’: African-American Soldiers in the Philippine-American War, 1899-1902.” The Journal of African American History 99, no. 3 (2014): 197-222. http://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.99.3.0197.

“Voices from the Philippines: Colored Troops on Duty—Opinions of the Natives.” Richmond Planet. (Richmond, Va.), 30 Dec. 1899. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/1899-12-30/ed-1/seq-1/.

December 30, 2020

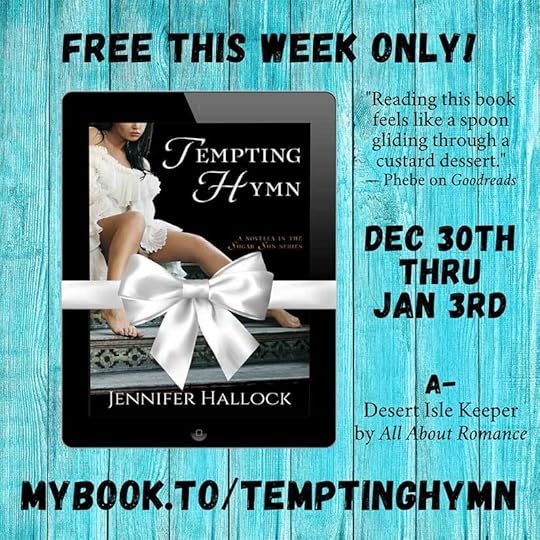

Tempting Hymn is Free!

Happy New Year! Good riddance, 2020. To celebrate, Tempting Hymn is completely free on Amazon! The giveaway lasts from December 30th to January 3rd only, so get your copy now.

Jonas Vanderburg needs Rosa Ramos’s help to rebuild both his health and his life. But Rosa is scared to pin her future on the promises of yet another American. Leaving hospital together is not the biggest challenge for these two people from different faiths, countries, and generations: the missionary mafia that controls colonial Philippine society may never bless their union.

This is a steamy, historical, and cross-cultural marriage-of-convenience novella. If you like strong-but-silent blue-collar heroes and clever nurse heroines, this is the book for you. In a pandemic year, content guidance is more important to you than ever. A full list—including epidemic disease (cholera)—can be found here.

Named a Desert Isle Keeper from All About Romance: “If you like underrepresented settings, social class conflict, intercultural romance, working-class characters, or just damn good historicals, the Sugar Sun series is one to get into. I’m certainly developing a sweet tooth!”

More praise for Tempting Hymn, a novella in the Sugar Sun series:

“I told myself I would go to bed early, but then I opened Tempting Hymn.” (Amazon Reviewer)

“Tempting Hymn manages to give adequate breathing room to the harsh historical realities of American colonial rule in the Philippines, while delivering a romance that is sweet, realistic and—above all—emotional. . . . Hallock doesn’t pull any punches in Tempting Hymn, with either the romance or the historical detail. She does her setting and her characters justice, delivering a story that is raw and unflinching, but never too dark, because it has an engaging and touching romance at its core. [And] all the sex scenes here are insanely hot, just like in Under a Sugar Sun.” (Dani St. Clair, Romancing the Social Sciences)

“This novella does a hell of a lot of work between the lines. It’s actually breathtaking.” (Kat at BookThingo, posted on Twitter)

“The pairing here is American man/Filipino woman and that is a tricky, sensitive trope…but it’s handled with deft and care. And dignity.” (Mina V. Esguerra, author of Iris After the Incident, reviewed on Facebook)

“…the first love scene between Jonas and Rosa is a master class.” (Bianca Mori, author of the Takedown trilogy, reviewed on Goodreads)

December 26, 2020

The Writer’s Toobox: Character & Setting Tools

In addition to the research guidance that I offer in my Micro-History Workshop, I have collected a slew of tools that I use regularly to enhance my character and setting development.

Do you need to name a hero or heroine? Plan a heroine’s pregnancy? Determine the (likely) color of a child’s eyes? Get some dos and don’ts in describing skin color? Follow this link to learn more.

Do you want to view the same sky as your characters? Make a best guess at future weather, with or without a farmer’s almanac? Find a historical map of your chosen city—or make your own? Find out what plants or animals are indigenous to the region? Follow this link to learn more.

The Writer’s Toolbox: Setting Development

In another post, I showed you amazing free sites online that can help with character development. For some books, though, the physical environment is a character itself, and it needs to be developed just as thoroughly—but differently.

Here are some tools for where (and when) your story might take place:

On my character development page, I talk about the usefulness of Timeanddate.com for moon phases, but—oh my—move over T&D because there’s a new web technology in the house, and it’s awesome, in the traditional grand scope of that word. Meet the Stellarium online star map.

On my character development page, I talk about the usefulness of Timeanddate.com for moon phases, but—oh my—move over T&D because there’s a new web technology in the house, and it’s awesome, in the traditional grand scope of that word. Meet the Stellarium online star map.

First, choose your setting: click on the left corner rectangle that probably starts with “unknown” or maybe your current location. You can add in an address, or even just a city, and move the pointer exactly where you want it. Below is the location for my fictional San Honorato chapel.

Then choose your date and time with the controls that pop out of the bottom right corner. The slider shows you how the sky changes over the course of the evening.

And then, wow. You’re there. Just like your characters. Amazing! You can ask the program to draw constellations for you, to represent them artistically, or even to take the ground away altogether.

I have just barely scratched the surface, and no doubt there are many other amazing features. For example, if you want to take this outside to use for your night sky, choose the night view button that makes the screen red and black to help your eyes stay adjusted and avoid light pollution for gazing. Go play.

Tides4Fishing will give you detailed information on the rising and setting of the sun, solunar activity, moon phase, and astronomical observation data. However, it is best used for tidal data like the name suggests. How many beach-set books forget to talk about high tide or low tide? Yet it is the first thing you notice when you are actually on a beach because it determines how much sand you have right in front of you.

Tides4Fishing will give you detailed information on the rising and setting of the sun, solunar activity, moon phase, and astronomical observation data. However, it is best used for tidal data like the name suggests. How many beach-set books forget to talk about high tide or low tide? Yet it is the first thing you notice when you are actually on a beach because it determines how much sand you have right in front of you.

This site only has historical data back a few years, but I find that if you generally get the right time of year and the right moon phase, it works well enough.

I have found no better weather site than WeatherSpark.com—not for your immediate forecast, but for average historical data? You bet. (You can also check out the Farmer’s Almanac website here.)

The diagram above has a little of everything they offer: from clouds in the sky to precipitation, humidity, temperature, and “beach/pool score” (defined as the number of “clear, rainless days with perceived temperatures between 75°F and 90°F”). Honestly, it is also useful for vacation planning.

Have you ever thought to yourself, “How likely would it precipitate on such-and-such a date?” Now you can snow in your couple at a lovely cabin in Aspen over Thanksgiving, assured that this plot device is totally plausible. I love forced proximity romances, by the way, so gimme.

Everyone uses Google Maps, and so do I. But for authorly things I often prefer Mapcarta. This free service uses OpenStreetMap and Wikipedia, but this is one of the clearest topographic maps I have found, especially as the topography can be laid directly over a street map.

A slice of the mountain ridge east of Bais, shown in topographic detail from Mapcarta. This is where Andres heads up to barangay chapels to offer mass and hear confessions.

A slice of the mountain ridge east of Bais, shown in topographic detail from Mapcarta. This is where Andres heads up to barangay chapels to offer mass and hear confessions.Or . . . what if you do not know exactly where you want to locate your story? You need someone to lay photos over the map, like VH1s old Pop-Up Video, so you can choose a location. Mapcarta has done exactly that but (sadly?) without the 80s music. As you linger over one of the circles, the site will enlarge it and even give you a big close-up.

Here is a Mapcarta photo slice of Lebanon, where I used to live, extending into Syria, which was one of my favorite places to travel. Yeah, it’s too bad.

Here is a Mapcarta photo slice of Lebanon, where I used to live, extending into Syria, which was one of my favorite places to travel. Yeah, it’s too bad.

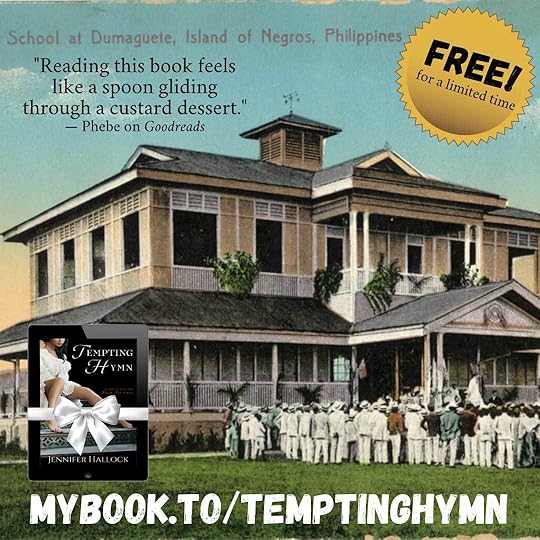

Don’t forget the obvious. YouTube is owned by Google, which is why I recommend using the Google Video search bar. This gives you more tools to limit your results, though beware that date refers to date uploaded. I searched “New York 1900” and look what I found:

Another quick tip: use social media like Instagram and Facebook to search places for user photos too!

For historical authors, detailed maps of how cities used to look are essential. For example, Locating London’s Past, with GIS-compliant data-rich maps is a great resource for those setting their book there. For other cities, a specific Google search may be your first stop. Your second stop? Your target city’s library and any digital map collections they might have.

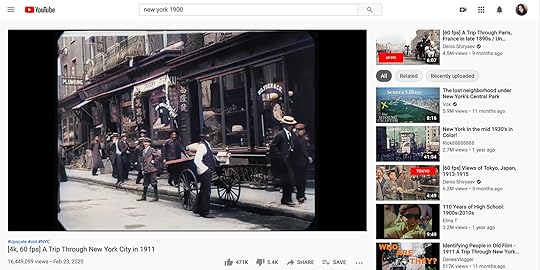

But where next? Try the University of Texas at Austin’s Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. They have maps from all over the world, on topics from population to transportation to history. You can start by browsing their curated collections:

Or you can search for a particular country and look at everything they have. This is the current collection of historical maps on the Philippines:

Most of these maps are government publications, which means they were never in copyright and can be used in commercial publications.

If you want privately published maps—many of which are out of copyright and may be downloaded in high-resolution files—check out David Rumsey‘s collection. Most of the downloads are free, but you can purchase prints, even framed prints, directly from the site. With maps like this one from Time, I can see the appeal.

There are also maps that function more like posters, like this one from the Gay Freedom San Francisco movement in 1980:

I found excellent historical maps of Boston in this collection, and I used these to help construct the backstory of my first heroine, Georgina Potter. I knew her address before the story began, though it never once came up in the book itself. Does anyone else go a little too deep into their characters’ backstories, even if just in their heads? Okay, maybe it’s just me.

And if you are not writing historicals? What about science fiction. This site has interactive planetary maps, too, like this one of Venus.

What if you don’t want to use a map but make a map? Stamen is a “data visualization and cartography design studio” that has worked for pretty much every major museum and Fortune 500 company. For the rest of us, they have made some great tools for downloading open-source maps for our own illustrations. First, choose among many different options, three of which you can see below:

Then, enter the place you want—and, yes, it has to be a real place. This is Columbus, Ohio, my own hometown, and the origin of my next heroine, Dr. Elizabeth Shepherd.

Click on and you are given options for downloading a portion of the map. Check out the watercolor base for my Sugar Sun series map of Bais:

Amazing, right? It’s actually even prettier in the download. Here’s what I whipped up for my readers:

This is a quick map of the Bais of my mind, the setting of the Sugar Sun series. Watercolor map from the open source tools of Stamen Design.

This is a quick map of the Bais of my mind, the setting of the Sugar Sun series. Watercolor map from the open source tools of Stamen Design.

Do you want to disappear down a museum rabbit hole? Google’s got that. They have digitized collections from over 100 global museums and cultural sites, particularly useful for the budget (or pandemic) constrained.

Do you want to disappear down a museum rabbit hole? Google’s got that. They have digitized collections from over 100 global museums and cultural sites, particularly useful for the budget (or pandemic) constrained.

While nothing here can be downloaded, obviously screen grabs work pretty well.

I particularly appreciate Google’s work with non-profit and academic institutions to bring ancient sites to life. I plan to use these in my teaching.

And, of course, they have both world wars pretty much covered:

I have just scratched the surface here. Go lose yourself.

One of the most important aspects of setting is what flowers you smell or what animals you see crossing the road. Whether flora or fauna, the GBIF database is incredibly powerful. If you know the species name of what you want, this site will show you where and when it has been sampled or observed. It will also give you a lot of data that I cannot really explain what to do with, but maybe you will figure it out. (The lack of science in my post-secondary education is obvious.)

Dolphin populations in the Philippines from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

Dolphin populations in the Philippines from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.In order to find the record of any particular specimen, you cannot just click on the dot, which is not the greatest user interface. But if you use the limit tool underneath the zoom out button, you can find the information you want.

If you are just looking for plants, Plants of the World Online is another excellent metasearch engine.

Because my character Liddy is a fern fanatic, I have been using a few fern sites, like Ferns and Lycophytes of the World and the Pteridophyte Collections Consortium. But the first site above, GBIF, is a one-stop-shop, and I wish I had found it earlier.

There is one other important type of map, and there is only one person making them: sensory maps. You got it: what does your scene smell like?

There is one other important type of map, and there is only one person making them: sensory maps. You got it: what does your scene smell like?

You can read more about artist Kate McLean and her project on Atlas Obscura. If you want the maps themselves, you have to go to her own website, SensoryMaps.com. There you can find illustrations that ask questions like, “What did ancient Rome smell like?”

Smell is the sense too often forgotten in writing. See if Kate McLean can help you fix that.

Thank you for checking out this blog post. I hope the tools I have found are helpful to you, and feel free to contact me if you have other suggestions. Thank you for visiting!

December 24, 2020

Pandemic Christmas #MaskUp

In the past, this is what I thought a pandemic Christmas looked like:

For bonus points: what is the star at the top of the tree? Hint: it’s a “major award.” #AChristmasStory

For bonus points: what is the star at the top of the tree? Hint: it’s a “major award.” #AChristmasStoryMr. Hallock and I have each other—and Wile E, seen below—and for this bounty, I am extremely thankful. We are spending our holiday watching This Farming Life, Your Home Made Perfect, and Country House Secrets.

(I highly recommend the last one, Mary Berry’s new show, for anyone writing in the British historical romance chronotope. Big house parties are the theme, and the first episode begins with Highclere Castle—or, as you likely know it, Downton Abbey!)

Wile E. is caught here mid-wag. Check out the river, as calm as mirror glass. She needs her bright orange vest just in case. It is hunting season, and she sorta looks like a dumb deer, no?

Wile E. is caught here mid-wag. Check out the river, as calm as mirror glass. She needs her bright orange vest just in case. It is hunting season, and she sorta looks like a dumb deer, no?In case you were wondering, we did win our game of Pandemic. I mean, we cured all four diseases, which is all you need to do—not actually heal the infected. It all feels very 2021.

For slightly more festive posts from Christmases past, check out the links below. And, whichever holiday you celebrate, if any, everyone at Little Brick Books wishes you a safe, healthy, and happy one.

A 1960s Christmas postcard from the Philippines, courtesy of the fabulous Pinoy Kollektor website.

A 1960s Christmas postcard from the Philippines, courtesy of the fabulous Pinoy Kollektor website.

December 7, 2020

Gilded Age Medicine: Why Ordering Heroin from the Sears Catalog Was A Step Up

My favorite stuffed animal as a child was a weird-looking turtle named Snoozie. My bedtime stories were mostly Snoozie skits—half-Muppet Show, half Lion King—as written and performed by my father. When my beloved Snoozie tore a seam, my father stitched him up. The surgeon of the house did all the sewing. My father also removed my splinters with the tip of an eight-inch butcher’s knife. Since I could not stand to look at the knife, I watched his face as he concentrated. He never missed one, and it never hurt.

As I grew older, I loved to hear tales of my father’s training in medical school, like when he had to draw his own blood because his partner had passed out. He filled the syringe and handed it over when the other guy woke up. Another classmate devoted only one line in his notebook to each day’s lecture. Later, if anyone had a question about what was said a month ago in physiology, this fellow would look up the right dated line and reprise the professor’s entire hour-long talk verbatim, even the bad jokes.

Despite this steady diet of stories, my father did not believe in pressuring his only child to follow in his footsteps—not that it was much of a choice for me after college. I am a bit embarrassed to admit that I did not take a single laboratory science course after high school, and that omission would have been a problem on my application—in the 1990s. In the 1890s, not so much. Harvard Medical School accepted nearly all applicants. Well, all male applicants. The president of the university considered coeducation “a thoroughly wrong idea which is rapidly disappearing.”

Sugar Communion’s heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd, as inspired by an 1896 fashion plate at the Met. (She will borrow the dress.)

Sugar Communion’s heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd, as inspired by an 1896 fashion plate at the Met. (She will borrow the dress.)Fortunately, coeducation did not disappear and, also fortunately, other medical schools at the time did accept women, including the predecessor of Ohio State—where my next heroine, Liddy, will be trained. (My father went there, too, in the 1960s.)

Ohio Medical University was one of the predecessor institutions of the eventual Ohio State University Medical School, and the affiliated Protestant Hospital would eventually become Riverside Methodist Hospital. This original campus was at Goodale Park. Postcard courtesy of Historical Reflections, the Ohio State Medical Heritage Center Blog.

Ohio Medical University was one of the predecessor institutions of the eventual Ohio State University Medical School, and the affiliated Protestant Hospital would eventually become Riverside Methodist Hospital. This original campus was at Goodale Park. Postcard courtesy of Historical Reflections, the Ohio State Medical Heritage Center Blog.Liddy will be unusual because she will have a bachelor’s degree when she starts medical school—something only eight percent of American medical students had in 1894, when she began. Typically those eight percent probably came from the bottom of their respective college classes. Scholars with promise went into teaching or the clergy. Physicians were considered “coarse and uncultivated . . . devoid of intellectual interests.” There was a real danger that too much science would “overcrowd” their limited minds. There were no written examinations at Harvard Medical School. None. In fact, that would have been impossible, one professor complained, because half of his students “could barely write.” He was not making a joke about doctors’ poor penmanship.

How could this be?

The Humoral System (Pre-Gilded Age)

Let’s talk first about what we know about what makes us sick. For far too long—from the ancient Greeks to the middle of the Victorian age—the European system of medicine described the human body as a balance of four substances called humors. If you had too much blood, the first of the four, it made you sanguine—courageous, hopeful, even amorous. Too much yellow bile turned you choleric, or hot-tempered. Black bile produced melancholic scholars, Shakespeare’s favorite. Too much phlegm slowed you down, made you apathetic. Your “sense of humor,” as it was known, even dictated which internal organs were most likely to fail you, like a combined CT-scan-slash-Meyers-Briggs personality test.

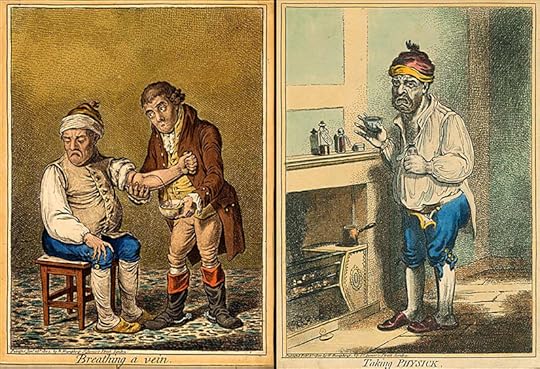

James Gillray’s “Breathing a Vein” and “Taking Physick” (calomel), published by H. Humphrey, 27 St. James’s Street, London, January 26, 1804. Images courtesy of the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia.

James Gillray’s “Breathing a Vein” and “Taking Physick” (calomel), published by H. Humphrey, 27 St. James’s Street, London, January 26, 1804. Images courtesy of the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library at the University of Virginia.Blood was the only humor that could be spilled on command, so bleeding became the inevitable treatment for any imbalance. If you were sick in the eighteenth century, you headed off to your neighborhood barber-surgeon, maybe get a few teeth pulled while you were there. In 1793, when Founding Father Dr. Benjamin Rush faced a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia—then the nation’s capital—he treated one hundred people a day by draining two liters of blood per person. That’s about forty percent of the blood in their bodies! Half of Rush’s patients died. When George Washington fell ill from a throat infection in 1799, he was bled the same amount by his doctor. He died. Washington’s physician, like Rush before him, and like the barber-surgeons before them, used a specific scalpel named after a medieval weapon. It was called a “little lance,” or a lancet. A publication named The Lancet was and still is a leading medical journal. That’s like naming an education blog The Paddle.

“Leeches, a type of worm with suckers at both ends of the body, were used in bloodletting. It was the job of the leech finders, usually women, to collect these creatures for medical use. The leeches attached themselves to the legs and feet of the women who plucked them off and stored them in the little barrels of water. Doctors grew rich at the expense of these low paid women. Leeches were such a popular treatment that by 1830 demand outstripped supply all over Europe. Today, leeches are used following plastic and reconstructive surgery as they help restore blood flow and circulation. The print appeared in Costume of Yorkshire, published by George Walker in 1814.” Image and caption from the Science Museum Group.

“Leeches, a type of worm with suckers at both ends of the body, were used in bloodletting. It was the job of the leech finders, usually women, to collect these creatures for medical use. The leeches attached themselves to the legs and feet of the women who plucked them off and stored them in the little barrels of water. Doctors grew rich at the expense of these low paid women. Leeches were such a popular treatment that by 1830 demand outstripped supply all over Europe. Today, leeches are used following plastic and reconstructive surgery as they help restore blood flow and circulation. The print appeared in Costume of Yorkshire, published by George Walker in 1814.” Image and caption from the Science Museum Group.Less extreme than the lancet were leeches, or parasitic worms. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Britain imported 42 million leeches a year, seven million for London alone. That was about three leeches per person, but it still wasn’t enough. One British doctor admitted to using the same leeches on fifty different patients in succession—not realizing that he was exposing that fiftieth patient to blood-borne diseases from the last forty-nine people he treated. No wonder Napoleon called medicine “the science of murderers.”

Calomel display from the Musée Testut-Latarjet.

Calomel display from the Musée Testut-Latarjet.He should know. He had been given another favorite prescription of the age: calomel, or mercurous chloride, which was prescribed as a magical tonic for almost any ailment, from tuberculosis to ingrown toenails. It was another humoralist treatment: when you could not take any more blood, purge your patient from both ends with this substance that made them vomit and gave them diarrhea: powdered mercury. Among the many, many symptoms of mercury poisoning are tremors, loss of teeth, and amnesia. Oh, and death.

No, I’m not blowing smoke up your ass. Wait, did you ever wonder why we say such a thing? The biggest fear of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was, shockingly, not doctors themselves but their doctors burying them alive. George Washington’s last words were instructions not to conduct any funeral for three days, just in case his physicians were not capable of distinguishing between life and death. Apparently, he had not heard of the latest sure-fire test, a tobacco smoke enema. Blowing smoke through a tube into a person’s nether region was sure to animate any phlegmatic—even before Dr. Previnaire added a bellows, a hand-held blower like I use in my fireplace, to create his patented anal tobacco furnace. The Academy of Sciences in Brussels gave Dr. Previnaire a prize for his work (Bondeson 139).

Resuscitation Set from the first half of the 19th century, courtesy of the Science Museum Group.

Resuscitation Set from the first half of the 19th century, courtesy of the Science Museum Group.This is not medicine, you say; it’s snake oil! Absolutely, another popular remedy.

There were some bright spots. British Naval surgeon Dr. James Lind discovered that oranges and lemons helped his sailors recover from scurvy, but he did not know why. He did not even know what Vitamin C was. Still locked into a humoralist mindset, he believed scurvy was caused by cold, wet sea air and a lack of exercise. And, yes, vaccination did exist at this time—in fact, a form of vaccination has been around for a thousand years—but again no one could explain how it worked.

It was not until the population medicine studies of Pierre Louis in 1820s and 1830s France that people looked at the data and said maybe bleeding doesn’t work. Louis introduced a new way of examining the efficacy of treatment: looking at large numbers of similar patients and studying their reactions to different applications of medicine. It was the first baby step toward clinical trials, though it was not yet randomized and his sample sizes were not very large.

Bloodletting faded from life slower than the patients who were being bled. Despite a very public debate between doctors in the 1850s, the practice persisted in textbooks as late as 1942. One part of the appeal may have been its accessibility and affordability. There were bloodletters everywhere, and they were cheap “health care.”

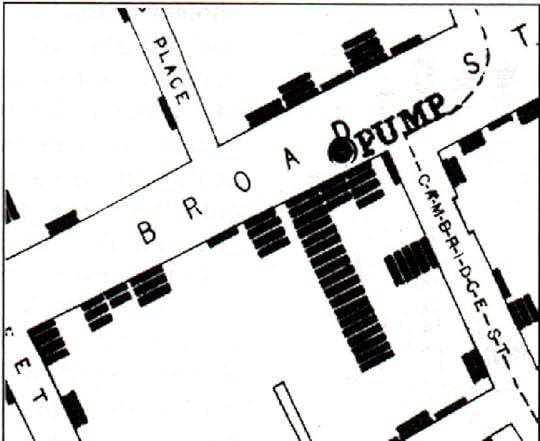

Another reason it persisted: no one had yet proven another theory of disease. All the pieces were there. Contagion was not a new concept: even as far back as the Islamic scholar Ibn Sina, there was an idea that disease could be spread by touch. Animalcules, or microscopic organisms had been seen as early as the 1670s. Dr. John Snow (not that Jon Snow) had shown it was not miasma, noxious urban gasses, that caused cholera but something the sick had passed to the water through their feces. Snow did not make this discovery with a microscope, though, but with a map showing clusters of cases around certain well pumps.

Snow’s map of cholera deaths in the Broad Street area, courtesy of the Department of Epidemiology, at the University of California Los Angeles School of Public Health.

Snow’s map of cholera deaths in the Broad Street area, courtesy of the Department of Epidemiology, at the University of California Los Angeles School of Public Health.But Snow did not really change long-term thinking. The handle was reinstalled on the Broad Street pump in London a couple of weeks later, after the cholera crisis had passed. Maybe, they thought, Snow did not really know what he was talking about. Mysterious waterborne poison, indeed.

Gilded Age Medicine

You cannot change the answers until you change the questions. And you cannot change the questions until you admit what you don’t know. What was in the air—or water—that we were not seeing? At the beginning of the Gilded Age, Louis Pasteur introduced an anthrax vaccine in 1881 and a rabies vaccine in 1885. Pasteur’s best frenemy, German physician Robert Koch, isolated the bacterium that causes tuberculosis in 1882. In 1884, he did the same for cholera. These were four of the worst disease bogeymen of the modern age. Modern bacteriology was born.

By the way, the man who introduced these two rivals, Koch and Pasteur, was Dr. Joseph Lister, the first surgeon to disinfect wounds and sterilize surgical equipment. You know his name as the root of the brand name Listerine. Yes, you are rinsing your mouth with surgical antiseptic. Please continue to do so.

A compound microscope from the 1880s and a vintage bottle of Listerine, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A compound microscope from the 1880s and a vintage bottle of Listerine, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.It would take time before the best and brightest of the American college set would pursue a career in medicine. And, like my character Liddy, if you wanted the best post-graduate education, you really had to go to Europe. While earlier in the century that may have meant Edinburgh or Paris, by 1890 that meant Germany or Austria, and in particular the Allgemeines Krankenhaus (General Hospital) of Vienna. (And you ate dinner at the Riedhof too!)

Wien Wickenburggasse mit Riedhof, outside the Vienna General Hospital. Photo from vintage postcard.

Wien Wickenburggasse mit Riedhof, outside the Vienna General Hospital. Photo from vintage postcard.Back in the US, it was not until 1910 that medical education truly changed. Two of the richest men to ever live, John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, funded the Flexner Report, which was like an early US News & World Report ranking guide to medical schools—and like all of those publications, it was deeply flawed. The publication of the Flexner Report in 1910 is credited with creating the modern scientific medical school system in the US, but it also directly or indirectly caused the closure of many medical schools for women and African Americans. Those that had been coeducational reduced their admission of women, partly because they had a rise in male applicants. One study calls an unintended consequence of Flexner’s report “the near elimination of women in the physician workforce between 1910 and 1970.”

The General Hospital of Vienna, a favorite place for post-graduate study for American medical students in the late 1800s. Illustration from Wikimedia Commons.

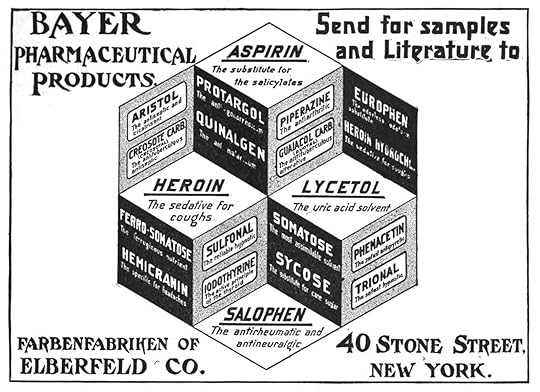

The General Hospital of Vienna, a favorite place for post-graduate study for American medical students in the late 1800s. Illustration from Wikimedia Commons.Nevertheless, the Gilded Age must have been very exciting to live through. Every day, it would seem, more diseases were being identified and explained. Notice that I did not say cured. Calomel was still popular in the early 1880s, as were chocolate-covered arsenic tablets. Aspirin existed, but no one knew how it worked until 1971! There still was no real anesthesia for surgery except ether and cocaine. Cocaine was quite handy, actually, and it was sold in lozenge form for toothaches. Bayer Pharmaceuticals introduced a new form of cough relief that they said was just as good as morphine, but not as habit-forming. They trademarked this miracle compound: Heroin. You could buy two vials for $1.50 from Sears, complete with carrying case and dosage instructions for children!

Heroin advertisement from p. 377 the November 1899 issue of the New York Lancet, accessed at Wikipedia Commons.

Heroin advertisement from p. 377 the November 1899 issue of the New York Lancet, accessed at Wikipedia Commons.Paul Ehrlich was playing around with dye stains when he stumbled upon the inspiration for a chemotherapy treatment for syphilis that would eventually be known as Salvarsan. He and his assistant, Sahachirō Hata, introduced their “magic bullet” to the world in 1909. It was an actual medicine with laboratory-tested results, and really the importance of this fact cannot be overstated. There was no other treatment for syphilis at this time. (And masturbation was discouraged in the strongest moral terms. See more on syphilis in historical romance—or, really, the lack of it.) The administration of Salvarsan was technically complicated and cumbersome, though, and the disease had to be caught in time. Ehrlich had wanted to discover a “magic bullet” for what ailed us, but nothing was that simple. Eventually, post-Gilded Age, sulfa drugs were introduced (1930s) and penicillin shortly thereafter, but old habits of calomel and bloodletting died harder than they should have.

Modern Parallels

Opioid addiction rates are not the only modern parallels to Gilded Age medicine. We still distribute poisons that would make the merchants of mercury blush. For example, botulism bacteria produce a paralyzing substance so toxic that one teaspoon could kill as many as a million people. You know it as Botox, a medically recognized treatment for Cerebral Palsy and chronic migraines. Or you might have it injected into your face to smooth your wrinkles. No judgment.

Progress is not always a straight line. Leeches and maggots are making a comeback—raised in sterile conditions, fortunately, and shipped to an intensive care unit near you. The leech releases an enzyme that keeps blood vessels open, which is essential in reattachment surgery particularly in fingers and toes. Maggots are good for recurring ulcers of the skin caused by drug-resistant infections like MRSA. Maggots only eat dead tissue—as long as you get the right type—and also release an enzyme that promotes healing. And even bloodletting, or phlebotomy therapy, may be used today for specific diseases of overproduction of red and white blood cells and excess iron.

The medicine of World War I is also making a comeback. Bacteriophages are viruses that destroy bacteria. Honestly, they look like creepy spiders from a horror movie. They are hard to keep alive in transport—which is why they were tossed aside when antibiotics were discovered—but in an era of resistant superbugs, they may be the answer.

Microscopic images of nanostructural and biological bacteriophages, courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Microscopic images of nanostructural and biological bacteriophages, courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.My father is now retired from stitching up humans and stuffed animals. There are many talented, highly-trained, and impressive women and men who have taken his place. This Thanksgiving I am grateful for them all, from emergency room nurses to the scientists behind messenger RNA vaccine development. But if this somewhat sordid tour of medical history has taught us anything, it is this: whether you are doctor or patient, teacher or student, we need to keep in mind the wise words of 12th-century rabbi, scientist, and physician Maimonides: “Teach thy tongue to say ‘I do not know,’ and thou shalt progress.”

Even Maimonides should have trained his tongue better. After all, he believed in bloodletting.

I just could not help including this. It is the Allison “operating” table, as advertised on page 352 in the

New York Lancet

Maybe they’re going to try the tobacco smoke enema?

I just could not help including this. It is the Allison “operating” table, as advertised on page 352 in the

New York Lancet

Maybe they’re going to try the tobacco smoke enema?Want to know more about the history of medicine? I used a collection of podcasts introduced in my previous post, and I cannot recommend them highly enough! For more on sex education manuals of the time, check out my random sampling.

October 4, 2020

My Favorite Medical History Podcasts

In addition to an extensive list of memoirs, biographies, and research texts on medical history that I have read for background research on Sugar Communion, I have also spent a lot of time walking the dog and listening to podcasts. Here’s a photo of Wile E. and me, just because:

Heading out to the trail and hoping we’re the only ones on it. Listening to medical podcasts during COVID is on-point.

Heading out to the trail and hoping we’re the only ones on it. Listening to medical podcasts during COVID is on-point.My heroine, Dr. Elizabeth “Liddy” Shepherd, M.D., is one of many young women who became physicians or surgeons at the turn of the twentieth century. In romance novels, the introduction of a female doctor character is often presented as something truly exceptional: “the only female physician in England,” one says! While it is true that the best female physicians of the United Kingdom were in Scotland, not England, this kind of blurb is bad history. (Is it good marketing? I don’t know.)

Check out my Pinterest pages for all my inspirations and visual research. Liddy will grow up in a medical family: her father and two brothers are both physicians of the eclectic school and operate a hydrotherapy sanitarium (think Kellogg’s Battle Creek sanitarium for more frugal customers). She will go against her family’s wishes—not in becoming a doctor but in studying the new microbiological, laboratory-based field, which they regarded as a threat.

Check out my Pinterest pages for all my inspirations and visual research. Liddy will grow up in a medical family: her father and two brothers are both physicians of the eclectic school and operate a hydrotherapy sanitarium (think Kellogg’s Battle Creek sanitarium for more frugal customers). She will go against her family’s wishes—not in becoming a doctor but in studying the new microbiological, laboratory-based field, which they regarded as a threat.It was not an easy career to choose for a woman, to be sure, but doors were not as closed to them as people today tend to think. Modern medicine and medical education was born at the turn of the twentieth century, meaning that doctors went from being considered “butchers” and “charlatans” (though, let’s face it, they were bleeders) to people who could actually diagnose what was wrong with you and, eventually, help you. (Though before antibiotics, odds on recovery were still not great, unfortunately.) It is this improvement in status of doctors that led conservative elements of American society to decide that medicine was not an appropriate career for women, often because a woman doctor would be “taking the good job of a man.” The publication of the Flexner Report in 1910 is credited with creating the modern scientific medical school system in the US, but it also directly or indirectly caused the closure of many medical schools for women (and African Americans). Those that had been coeducational reduced their admission of women, partly because they had a rise in male applicants. One study calls an unintended consequence of Flexner’s report the “the near elimination of women in the physician workforce between 1910 and 1970.”

(Side note: Johns Hopkins, the model of a modern medical school for Mr. Flexner, only managed to operate because of the patronage of four women: Martha Carey Thomas, Mary Elizabeth Garrett, Elizabeth King, and Mary Gwinn. According to Johns Hopkins: “They would raise the $500,000 needed to open the school and pay for a medical school building, but only if the school would open its doors to qualified women. Reluctantly, the men agreed.” Unfortunately, the legendary founder of internal medicine at Hopkins, Dr. William Osler, was less enthusiastic about the role of women in the field, and the numbers of female students would dwindle before growing again decades later.)

Women in medicine is really the subject for another post, which I plan to do. But importantly I write historical fiction and romance, so my character Liddy needs to be a good doctor appropriate to her time period. I had to understand the world of medicine she was a part of. Better than studying it, I had to immerse myself in it. For that task, I did use some good books, but mostly I listened to podcasts. Let’s talk about a few of those:

Bedside Rounds

My favorite serious medical history podcast was Bedside Rounds, hosted by Adam Rodman, M.D. Every one of these episodes are very engaging and informative. How accurate are they? Well, members of the American College of Physicians can earn Continuing Medical Education (CME) and Maintenance of Certification (MOC) credit for just listening to these episodes and taking a quick quiz! But, trust me, we general listeners need not worry about the test. You’re definitely not going to get bored, either. Dr. Rodman’s intention was to model his podcast on Radio Lab, and he succeeded. His delivery of information is that compelling and digestible (health-related pun?). There were times when I did backtrack 15 seconds or so just to let some point wash over me a second time, but keep in mind that I was taking mental notes for my book. A casual listener can easily stay on pace. Dr. Rodman explains all his medical terms for us laymen, but at the same time he doesn’t shy away from the tough stuff. His presentations are well-scripted and do have lighter moments but never get silly. The Radio Lab comparison is dead on. I have listened to all 57 episodes (well, okay, 56 really because he revised and re-released one, and I only bothered with the newer version), and I will say that the whole series is fascinating. This library of information changes the way you view medicine. Frankly, it makes you realize how young the field really is. (Note: The COVID-related episodes, including an in-depth treatment of previous coronaviruses and the 1918 flu, are very good.)

This podcast will kill you