Michelle Cox's Blog, page 42

December 30, 2015

“She Hated Men With a Passion!”

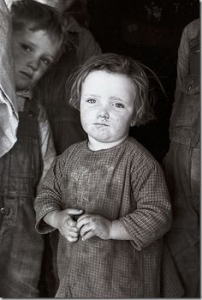

Anna Andziulewicz was born on December 26, 1906 in Pennsylvania to Polish immigrants, but later changed her name to Ann Andy. She was one of six children, including two sets of twins, of which Ann was one. At age three, however, Ann’s twin died, possibly of the flu epidemic. Then when Ann was six, her mother also died, leaving her father distraught and unable to care for the five remaining children. His sister came to live with them for a while, but she eventually had to return to her own family, leaving the father again confused and grieving.

Anna Andziulewicz was born on December 26, 1906 in Pennsylvania to Polish immigrants, but later changed her name to Ann Andy. She was one of six children, including two sets of twins, of which Ann was one. At age three, however, Ann’s twin died, possibly of the flu epidemic. Then when Ann was six, her mother also died, leaving her father distraught and unable to care for the five remaining children. His sister came to live with them for a while, but she eventually had to return to her own family, leaving the father again confused and grieving.

Not knowing what to do, Ann’s father turned to his parish priest, who in turn advised him to put the children in an orphanage. This was quite common in the early part of the last century. Many children in orphanages actually had living parents who for one reason or another couldn’t care for their children and so sent them away. Ann and her sisters were separated from her brothers and placed in two different facilities. Ann’s father visited often, but he, too, died young, making them truly orphans in more than name.

When Ann turned sixteen, the nuns at the orphanage sent Ann to St. Mary of Nazareth School of Nursing in Chicago. Ann did well there and made many friends and eventually became a nurse. She had learned how to do fancy embroidery work at the orphanage and continued to do it as a hobby even after she left. She enjoyed it so much that she formed a sewing circle with some of the other nursing students at St. Mary, and it was at about this time that she met her life-long friend, Alice Stanislaw.

Ann was apparently a very independent, tough, private person, perhaps because she needed to be to survive all those years in the orphanage. Though very cognizant, intelligent and able to express herself, Ann refused to give any information for this interview. All of the information has been supplied by Alice’s daughter, Margaret, who grew up calling Ann her aunt.

Margaret reports that Ann never married and, indeed, “hated men with a passion.” She thinks perhaps it has something to do with an incident that occurred at the orphanage when Ann was very young. Apparently, Ann’s sister was raped by a priest in the orphanage and later suffered a mental breakdown because of it. She was sent away to a mental institution, and Ann never saw her again. Her little brother was also later killed in a farm brawl somewhere in Nebraska, which Ann never understood, as he was a very timid, gentle soul. Both of these things affected her very deeply, and she was never able to really forgive. Margaret says that though Ann was kind and loving to those in her immediate circle, she was at the same time very particular and stubborn. Margaret says that her mother often tried to ease some of the bitterness Ann harbored, but it was difficult.

Ann traded in a husband and children for a career as a private duty nurse and travel. She traveled the whole world and spent some of her winters in Florida where she enjoyed walking on the beach and talking to local fishermen. She never had any hobbies besides sewing and did not belong to any church, saying that she did not believe in organized religion.

She was admitted to the nursing home after surgery for a colostomy and remains extremely depressed, saying she only wants to die. “My life is over. Look at me,” she says to staff. She refuses to get involved in the activities at the home and even to get out of bed some days. Despite the success she made of her life in many ways, she has never been able to escape the pain and bitterness of her early days.

The post “She Hated Men With a Passion!” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 23, 2015

Special Christmas Edition

In honor of Christmas and of the forgotten Chicago residents of Czech/Slovak/Bohemian descent, many of whose true-life stories populate “Novel Notes of Local Lore,” this week’s blog will include a round-up of intriguing Czech Christmas customs:

In honor of Christmas and of the forgotten Chicago residents of Czech/Slovak/Bohemian descent, many of whose true-life stories populate “Novel Notes of Local Lore,” this week’s blog will include a round-up of intriguing Czech Christmas customs:

Regarding Dinner:

No lights should be lit in the house before the first star comes out. After it does, dinner is served.

The table should be set for an even number of guests. An odd number brings bad luck or death.

No one should sit with their back to the door.

No one should ever get up from the Christmas table before dinner is finished. Doing so brings bad luck and death in the family. Also, the first person to leave the table after dinner will be the first one to die in the coming year, which is why everyone should get up from the table at the same time.

Any leftovers from dinner (crumbs, fish bones, etc.) should be buried around the trees to ensure they will bear lots of fruit.

Foretelling the Future:

The Floating of Walnut Shells: Little boats are made out of empty walnut shells and each family member places a little burning candle into a shell. Everyone’s shells are then floated on a bowl of water. If the shell makes it across the bowl, its owner will live a long and healthy life. A shell that sinks brings bad luck to its owner.

The Cutting of the Apple: After Christmas dinner, every person present at the table cuts an apple in half (crosswise, from the stem down). Both halves are shown to everyone around the table. If the core is shaped as a star, it means that everyone will get together next year in happiness and health. A four-pointed cross is a bad omen and means that someone at the table will fall ill or die within a year.

Foretelling Marriage:

Cherry Tree Twigs: On December 4, St. Barbara’s Day, an unmarried girl is supposed to cut a twig off of a cherry tree and put it in water. If the twig blooms by Christmas Eve, the girl will marry within a year.

The Throwing of the Shoe: An unmarried girl is supposed to throw a shoe over her shoulder and towards the door. If the shoe lands with the toe pointing towards the door, the girl will marry within a year.

The Shaking of the Elder Tree: An unmarried girl is supposed to shake an elder tree and if a dog barks, she will marry a man who lives in the direction from which the dog bark came.

Other Christmas Superstitions:

He who fasts all day until dinner will see the golden piglet on the wall.

After Christmas dinner, no field is to be crossed until the midnight mass. He who does so will die within a year.

He who fails to give a present on Christmas Eve will be met with poverty.

A pregnant woman will know whether she is carrying a boy or a girl once the first Christmas Eve visitor enters the house. If the visitor is female, for example, the baby will be a daughter.

Fish scales should be placed under Christmas dinner plates or under the tablecloth to bring wealth to the house. Carrying a fish scale in a wallet all year will ensure that money will not run out.

Have a very Merry Christmas and a Happy 2016!

The post Special Christmas Edition appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 17, 2015

“We Hid in the Walls”

Incredibly, Mercedes Murguia began life during the days of the infamous Pancho Villa. She was born on October 4, 1909 in Mexico to Vincent Munoz and Josephine Hildago. According to Mercedes, her great grandparents were Spaniards who controlled huge tracts of land in what is now Mexico. Her immediate grandparents were thus landowners who controlled the government, the school, the shops, the church, and put on all of the town’s holiday celebrations. They had beautiful adobe homes and orchards of fruit trees and lived a privileged existence.

Unfortunately, for them, however, it was also the time of the Mexican revolution, and Pancho Villa often raided the villages in the north of Mexico where Mercedes’ family lived. The men of the villages would go out to fight Pancho and his revolutionaries while the women and children hid in secret hiding places covered by wallpaper in the walls of the houses.

Mercedes says that she witnessed much violence and atrocities committed by Pancho and his men, including the hanging of two of her cousins. The worst incident involved the owner of an inn where Mercedes’ family happened to be hiding. Pancho Villa took the innkeeper, hung him by his feet and shot him in the head, then called dogs over to eat his brains. Mercedes says it is an image that will haunt her all her days.

Mercedes’ father, Vincent, was also man with a fiery temper who had spent a little time in the U.S. as a teenager working odd jobs, but returned to Mexico at some point and married Josephine Hildago. Despite the fact that Vincent was from a “well-to-do” family, he and Josephine and their nine children lived a life on the run, as it were, constantly moving throughout Mexico from town to town. Mercedes thinks that their nomadic life may have begun when Vincent killed his brother-in-law in front of his sister because he was “insanely” jealous of him. Mercedes says that Vincent was an alcoholic and smoked marijuana constantly and routinely beat Josephine and the children. Once he even beat the nine-month old Mercedes into unconsciousness.

But her father was not the only one Mercedes had to worry about. Because they were always working in factories in various towns they traveled through, Vincent and Josephine put their oldest daughter, Maria, in charge of the rest of the children and did not care what she did with them. Mercedes says she was every bit as bad as their father and cut switches from lemon trees to beat them until they bled.

When Mercedes was about ten years old, the family immigrated to Chicago, where Vincent and Josephine again found work in factories. Life seemed to get worse for Mercedes, however, as she grew older and began to look like the beautiful young woman her mother had once been. Josephine became extremely jealous and began being cruel to Mercedes as well. She was apparently the cause of many horrible fights between Vincent and Josephine, which resulted in Vincent beating Mercedes all the more.

Needless to say, Mercedes never really went to school and began working in factories until she met James Murguia, who convinced her to live with him with the promise of marrying her. She lived with James for five years, however, with no prospect of marriage in sight. One day, however, out of the blue, he offered to drive her to her factory job. This was unusual, but Mercedes agreed. Instead of driving her to the factory, however, he drove her to the courthouse to be married. Mercedes wasn’t sure she really wanted to marry him, but she was afraid to make a scene and humiliate him, so, in her words, “ I allowed myself to marry him because he was nice enough to ask me.”

Mercedes told him early on that she would not endure any beatings, which James agreed to and never attempted. Only once did he raise his hand to her, but she slapped him first. He never tried again. Together they had four children, but two of them died of cancer. James, too, died in 1954, leaving Mercedes alone to raise the kids. She worked as a housekeeper in a nursing home for 16 years to support them. Once the two surviving children left, Mercedes was alone for several years before she went to live with her brother, Jacob, with whom she became very close.

Mercedes was admitted to a nursing home after a fall in the hospital, where she had been admitted with an infected toe. Mercedes seems very accepting of her fate and is neither excited nor depressed by her admission. She does become distressed, however, when she hears other residents cry out as she is afraid they are somehow being beaten or abused by the staff. She says she has no hobbies except what other people “allow me to do.”

Despite being a victim of violence all of her life, or perhaps because of it, Mercedes Murguia remains a very submissive, forgiving person. She harbors no bitterness or anger towards the many people who have abused her over the years and says “I don’t let things bother me.”

The post “We Hid in the Walls” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 10, 2015

Living the Life of a Debutante

Elizabeth “Jane” Hileman was born on September 16, 1914. Her parents were Mary Alice Newell and Cleveland Hines Hileman, both of whom had quite an interesting story themselves.

Elizabeth “Jane” Hileman was born on September 16, 1914. Her parents were Mary Alice Newell and Cleveland Hines Hileman, both of whom had quite an interesting story themselves.

Mary was born in Ireland but immigrated to Port Huron, Michigan with her family when just a little girl. Cleveland, meanwhile, was of Danish descent and was born and raised on a farm in Geneva, Ohio. It turns out that as a young man, Cleveland took some sort of trip, whether it was for business or pleasure no one really knows, to Chicago. And on the day he passed through Union Station, he happened to spot Mary Newell across the Great Hall. She had come to Chicago to work, but hated her job and the city itself. She had decided, therefore, to quit and return home to Port Huron and was waiting for her train when Cleveland spotted her. Cleveland says he instantly fell in love with her and went over to introduce himself. They were married soon after and found an apartment in Edgewater at Winthrop and Ardmore, where they remained for 45 years. Cleveland worked as salesman for John Sexton Wholesale Grocers, and over time, he and Mary became rather wealthy. They were not able to have children, however, so they adopted a baby girl in 1914 and named her Elizabeth Jane.

Jane says that she was an only child and spoiled rotten. She also says that “people think adoption is bad, but I’ve never felt that way.” Jane can remember the days when Edgewater and Rogers Park were thriving and upscale. “People visited each other and had fun,” she says. “People socialized more.” She can remember coming home from school when she and her parents would put on their swimsuits and spend the evening at the beach. She says that people looked out for each other, and when it was particularly hot on summer nights, they sometimes slept at the beach with their neighbors. “If someone was murdered in the neighborhood back then,” Jane says, “it took us months to get over it. Now they just step over the body and keep walking!”

At one point in her childhood, Mary had to have an operation, and Jane had to go to a Catholic boarding school in Park Ridge while Mary recovered. Poor Jane was so bashful that she dressed and undressed in her tiny locker. She eventually returned to Edgewater and attended Senn High School, which, she says, was beautiful then and lived the life of a debutante. There were socials, and bridge games and fancy parties at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, where girls wore formal dresses and long evening gloves.

After graduating from high school, Jane attended the Art Institute and studied costume design. She says that she loved it and learned so much, not just about art. After she got her degree, she got a job as a commercial artist at Mrs. Overton’s Studio, the company responsible for designing the window displays at Marshall Fields. Jane oved her new career and relished in a very active social life.

At age 24, Jane met Paul Keely Barsaloux through friends, and they married three months after their first date in 1938. Cleveland got Paul a job at John Sexton Grocers, and Jane accordingly gave up her brilliant career in fashion and art when she got pregnant. They had three children: Steve, Linda, and Paul, Jr.

Paul and Jane lived for a time in Chicago before Paul got transferred to Oklahoma and then to West Virginia, where they lived for 7 years and which came to seem like home the most. It was about this time, that Paul and Jane’s marriage broke down. Paul had had several affairs over the years and now wanted out of the marriage, so they divorced, Jane returning to Chicago in 1955 with the three children, ages 13, 11 and 9, where she did the best she could to raise them on her own. Jane’s daughter Linda says that another man, Tom, may have come into Jane’s life at some point, but when asked about him, Jane will not elaborate.

Once the kids were raised, Jane moved to Hollywood, Florida where she spent the next 27 years and lived the life of “a loner,” according to Linda. She eventually returned to Chicago when she began having trouble managing on her own and found the adjustment very difficult. Linda finally took her to a doctor who has diagnosed her with Alzheimer’s. At this point, however, Jane is still very alert and aware of her condition. She knows that she is at times forgetful and gets frustrated when she can’t think of a specific word, but repeatedly says to the staff in the nursing home where she now resides, “I’m pretty good for being crazy!”

The post Living the Life of a Debutante appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 2, 2015

She Was Born “a Normal Little Girl”

Geraldine Chylik was born in Chicago on August 13, 1929 to Bohemian immigrants, George and Anna Chylik. George was a “heat treater” in a tool factory, and Anna sometimes worked in a grocery store when she wasn’t too ill. For the most part, though, Anna stayed home and cared for their four children. Geraldine’s medical chart records her as “mentally retarded,” but her younger sister, Doris, says she wasn’t always that way. Doris believes Geraldine was born “a normal little girl,” but when just a toddler, she fell down a flight of stairs. Apparently, the stairwell door had been left open by their drunken father, George, who was supposed to be watching them. Though no one knows for sure, the aunts in the family say that this is when Geraldine’s “retardation” began. Anna herself died before Doris was able to ask her mother what really happened that day.

Geraldine Chylik was born in Chicago on August 13, 1929 to Bohemian immigrants, George and Anna Chylik. George was a “heat treater” in a tool factory, and Anna sometimes worked in a grocery store when she wasn’t too ill. For the most part, though, Anna stayed home and cared for their four children. Geraldine’s medical chart records her as “mentally retarded,” but her younger sister, Doris, says she wasn’t always that way. Doris believes Geraldine was born “a normal little girl,” but when just a toddler, she fell down a flight of stairs. Apparently, the stairwell door had been left open by their drunken father, George, who was supposed to be watching them. Though no one knows for sure, the aunts in the family say that this is when Geraldine’s “retardation” began. Anna herself died before Doris was able to ask her mother what really happened that day.

At age 38, Anna discovered that she had a “poisonous, inward-growing goiter” that was inoperable because of an enlarged heart. Anna realized that she was dying but chose not to tell anyone, especially her husband, George. She knew she could not leave Geraldine in his care, as he was not only an alcoholic, but he was cruel to Geraldine as well, often teasing her and threatening to cut off all her hair, which never failed to throw Geraldine into hysterics. Not seeing any other choice, Anna took Geraldine to a mental institution at age 13 and left her there, hoping that she would be well cared for, despite Geraldine’s cries to be taken home.

Shortly after Geraldine’s placement, Anna was again admitted to the hospital, as she had been many times before. Upon being released, she was outraged when she returned home to find that George had not prepared anything for dinner as she had asked him to but found him drunk instead. She flew into a rage, yelling and screaming more than Doris had ever heard her before and then collapsed and died on the floor of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Upon his mother’s death, George Jr, the oldest at 17, promptly declared that he wasn’t going to “get stuck washing dishes and changing diapers,” and took off to join the navy. That left Doris, age 11, and Jimmy, age 10, to fend for themselves with the drunken and abusive George.

Geraldine was at some point transferred to another facility in Dixon, Illinois, and Doris eventually married and moved to Arkansas, both of which prevented her from visiting Geraldine. She has tried her hardest, though, to keep up a relationship with Geraldine over the phone. Both George, Jr. and Jimmy have refused over the years to have any contact with Geraldine, saying that she wouldn’t know them anyway. Doris has tried in vain to convince them to reach out to their sister, telling them that Geraldine still eagerly asks about both of them every single time Doris talks to her on the phone. Doris says that Geraldine instantly recognizes her voice and still asks about various family members from long ago. Her aunts have told Doris that as a child, Geraldine loved her brothers and sisters very much and was very protective of them, despite her damaged mind. She missed them terribly when she was institutionalized.

As she has grown older, Geraldine has been transferred to various nursing homes around Illinois, though Doris has been trying to get her into a facility in Arkansas near her. She knows little of her sister, really, except that she still seems to love her siblings. According to various chart records in the many facilities she has been a resident of, she has no hobbies or interests and seems only to find some comfort in music.

The post She Was Born “a Normal Little Girl” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 26, 2015

“Start Breathing Very Slowly…”

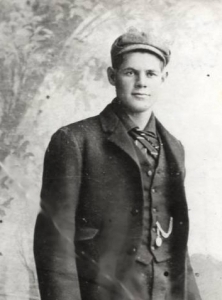

Ernest Jacobson was born on February 2, 1899, one of ten children living on a large farm in Sweden. He attended school until he was eleven, but began formally learning the trade of carpentry one night a week at age nine. The program was designed to teach boys to be full carpenters by the age of fourteen, which Ernest easily achieved.

Ernest Jacobson was born on February 2, 1899, one of ten children living on a large farm in Sweden. He attended school until he was eleven, but began formally learning the trade of carpentry one night a week at age nine. The program was designed to teach boys to be full carpenters by the age of fourteen, which Ernest easily achieved.

While still a teenager, Ernest found himself in the Swedish Calvary, but only for nine months, he says, since there were no wars going on at the time. When he was nineteen, he became the manager of a very large farm, but he quit after only a year, however, because he thought the owner to be a very mean, greedy man. Instead, he went back to his father’s farm and asked to manage it. His father, deeply in debt, agreed to let Ernest take over. His first decision was to cut and sell lumber from the acres of woods on the farm, which quickly cleared the debt and made the farm successful.

Ernest worked for his father until he was 27, at which time he decided to strike out on his own and left for America with his brother, Edwin. Their older sister, Hilda, had already immigrated to Denver, while their brother, Simon, had gone to Chicago, where he lived with his wife, Norma, and their two daughters. Ernest and Edwin made their way to Chicago and stayed with Simon and Norma their first summer in America. After that, however, Norma suggested the two brothers get their own place, as it was becoming too much for her.

Out of respect for Norma, Ernest soon found an apartment for himself and Edwin, where they lived together for three years before Ernest could no longer stand it. Edwin, it seems, was a bit of a trouble maker and had some pretty rough friends. It became apparent that one of them would have to go, and since Edwin was wanted by some shady characters throughout the city, he was the one to not only leave the apartment, but the city as well. He made his way to Denver to live with Hilda, but reportedly created havoc there, too.

Meanwhile, Ernest continued working as a carpenter, doing odd jobs, until the Depression hit and he found himself unemployed and hungry. At one point he went for eleven days without eating because he was too proud to ask for food. Eventually a friend offered to try to get him a job as a dishwasher in a restaurant. Ernest felt ashamed to have to rely on a friend, but in desperation he reluctantly went with him. At first the manager refused to hire him, saying that at age thirty-one, Ernest was too old, but he later changed his mind. As predicted, Ernest worked very hard, impressing the owner so much that he offered Ernest a job as the head maintenance man for his thirteen restaurants. Ernest gladly accepted and worked for this man for over thirty years.

Ernest had many sweethearts in Sweden and America, but never married. He had seen so many poor families over the years, he says, that he was determined not to have a family himself if he could not provide for them, and he always felt he could not. Instead, he traveled extensively with a friend and his family and worked until he was in his eighties. He remained fiercely independent and active into his nineties. Even at age ninety-five, he still went out shopping each day for “the old boys” in his apartment building who could not get out – most of them younger than him! – even on the coldest days for the year and never locked his door behind him.

Ernest was eventually admitted to a hospital after a neighbor called his niece, Jane (one of Simon and Norma’s little girls that he had lived with his first summer in America, incidentally), to report that Ernest was sick in bed. Ernest was taken by ambulance and diagnosed with pneumonia. From there he was sent to a nursing home to recover. When interviewed, Ernest was cognizant of the fact that he would most likely never go home again, but neither did he accept the nursing home as his new residence. His plan, instead, was simply to die “in a couple of weeks,” and to that end decided to “start breathing very slowly.” Until that time, however, Ernest remained a very positive, cheerful, sweet man who actively sought out other residents to talk to, his favorite discussions involving politics or religion.

The post “Start Breathing Very Slowly…” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 19, 2015

“I’m Losing My Mind…”

Oldrich “Al” Pakosta was born on January 3, 1913 to Stanley Pakosta and Marie Pajer, both Czechoslovakian immigrants who came to Chicago in 1908. Unfortunately, however, Marie died at age 31 when Al was just three years old. Stanley, a cabinet maker, remarried, and actually had a total of five wives, out-living them all! In fact, Al’s father died coming home from a girlfriend’s house on Christmas Eve, 1967, aged eighty-seven!

Oldrich “Al” Pakosta was born on January 3, 1913 to Stanley Pakosta and Marie Pajer, both Czechoslovakian immigrants who came to Chicago in 1908. Unfortunately, however, Marie died at age 31 when Al was just three years old. Stanley, a cabinet maker, remarried, and actually had a total of five wives, out-living them all! In fact, Al’s father died coming home from a girlfriend’s house on Christmas Eve, 1967, aged eighty-seven!

Al and his two older siblings grew up in Chicago and completed high school. Al worked as a cabinetmaker with his father and also as a machinist. His free time was usually spent with a cousin, John, who one fateful day let Al in on a secret as to where they could find a lot of good food. Not knowing what to expect, but always hungry, Al agreed to go with John in pursuit of this mysterious food source. He was shocked, then, when John drove him to – of all things – a farm in Riverdale, Illinois, which is now a south suburb of Chicago. John had a job delivering produce from the farm and gotten to know the people, who often let him keep bruised items, and had decided to let Al in on the spoils. For Al, however, the spoils were not to be the food. As he slowly climbed out of John’s truck, he noticed a young woman standing on the second step of the farmhouse. He looked up at her and just knew, then and there, that she was going to be his girl. Her name was Gertrude Popper, and she and Al were married on November 21, 1936.

Al and “Gert” got a little place in Chicago and over the course of their lives moved about between Cicero, Lisle, Berwyn, and finally Algonquin. They had one child, Charles, who was born on October 30, 1937.

Al had a variety of jobs over the years besides being a cabinetmaker and a machinist. He also worked for Diamond J trucks as an inspector and then for Harvester. He also owned two taverns – first the Tree Gables in Lisle and then the Court Inn in Cicero.

His favorite “occupation,” though, was playing saxophone, clarinet and piano in a local band called, Guy Pakee’s Orchestra. They even made a few records, of which Al is extremely proud. Al feels they had a great life together, he and Gert, and when they retired (Gert had sometimes worked in the Time Life building downtown), they decided to travel. They went to Europe, Alaska and even to Hawaii, and traveling became a great love of Al’s.

Their traveling days ended, however when Gert died unexpectedly of emphysema, which was also when Al’s “forgetfulness” began. Months after Gert’s death, he was often found by the neighbors, wandering, apparently lost, in the neighborhood. Charles, his son, who was living in Ohio and flying in every weekend to check on Al, finally took him to a doctor, who diagnosed him with early Alzheimer’s. Not knowing what else to do, Charles arranged for his father to go into a nursing home. Charles reports that Al agreed to this move, but now at the nursing home, Al is frustrated and upset and wants to go home.

As a way to deal with his anxiety, he at times makes jokes with the staff, but at other times, he can be found wandering the halls, desperately asking the staff if they have seen Gert. When they gently tell him that she is deceased, he bursts into tears as if hearing the sad news for the first time all over again.

The most heartbreaking part of Al’s condition is that he has moments of lucidity in which he seems to realize his condition, reporting to staff that “I can’t think straight” or that he fears he is “losing my mind,” though he does not know the cause. In these moments, he blames his forgetful state on a pinched nerve in his neck, which he says despondently, the doctors can do nothing about.

Now when Al anxiously asks the staff where Gert is, they simply tell him that she has gone out to the store, which seems to pacify him for a little while. He passes the time, waiting for her, in his room, listening to his Guy Pakee records on a little phonograph he has brought with him or looking at the scrapbooks of history and geography he has made over the years from newspaper clippings, as if in surrounding himself with the familiar, he can hang to… if even for a few moments…whatever part of his shattered mind still remains.

The post “I’m Losing My Mind…” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 11, 2015

“If It’s God’s Will, I’ll Make It”

Susan Ivik was born on January 27, 1900 to George Ivik and Katarina Turdon in Zariecie, Slovakia. George and Katarina immigrated to the United States and settled in the Pilsen area of Chicago in 1904. George found a job as a machine operator at Western Shade Co. and worked there until he died in 1925, whereupon, as a tribute to him, Western Shade shut down George’s machine and draped it in a black cloth for one whole day, a testimony to his hard work and ingenuity. Katarina was left with their nine children to care for, forcing most of them to quit school to find work.

Susan Ivik was born on January 27, 1900 to George Ivik and Katarina Turdon in Zariecie, Slovakia. George and Katarina immigrated to the United States and settled in the Pilsen area of Chicago in 1904. George found a job as a machine operator at Western Shade Co. and worked there until he died in 1925, whereupon, as a tribute to him, Western Shade shut down George’s machine and draped it in a black cloth for one whole day, a testimony to his hard work and ingenuity. Katarina was left with their nine children to care for, forcing most of them to quit school to find work.

Susan herself left school after finishing 8th grade and went live with a family friend, Mrs. Mickelson, where she got a job in the Loop at Western Union. Susan was a very independent, spirited young woman, involving herself in the temperance movement as well as the Red Cross during WWI. She wrapped bandages, sold war bonds door-to-door, and practiced marching in Grant Park with her fellow trainees in preparation for their planned trip to France to aid the soldiers there. The war ended, however, before they got a chance to go, and while they were overjoyed, of course, that the boys were coming home, there was a distinct feeling of disappointment that their adventure had been thwarted.

Not long after the war ended, Susan was walking home from work one day and passed down Jefferson Avenue where she saw a group of young men playing baseball in the street. One of them stopped playing and came over to talk with her. His name was Josef Hlavaty, and he later became Susan’s husband on October 16, 1916. Susan was just 16 years old; Josef was twenty.

Josef worked as a truck driver with the Teamsters and did not approve of Susan working, so she stayed home and raised their four children: Susan Rose; Eleanor; Josef, Jr.; and Edward. She also had twins who died after only 6 hours of life. According to her children, Susan seemed to enjoy her life as a housewife and cooked, baked and sewed everything from scratch and who was absolutely full of life.

Every summer she and the children packed up the car and traveled north of the city to the little village of Wauconda, where they had a summer cottage on the lake. Susan loved to fish, garden and read. She was a very intelligent woman and was very strong, and though she was in many accidents over the years, her children say that she never cried, complained or babied herself. They recount many stories of Susan’s misfortunes, including the time she was trapped in a burning car, the time she got her arm caught in a wringer and mangled, the time she stepped on a sickle and slashed her leg, the time she stepped on a rusty nail in Wauconda and drove herself to Chicago with a ballooned foot, the time she dug a fish hook out of her thumb, the time she split her finger open with an electrical saw, her various mild heart attacks, and the time she had her cancerous uterus removed. In all of these situations, her children say, Susan remained calm and cool. Her attitude is typified in a statement she made before her hysterectomy. “If it’s God’s will, I’ll make it; if it’s not, then I won’t!”

She was strong, too, when her husband, Josef, died in 1943 at age 47 of one of his “spells.” Afterwards, Susan lived alone with the children until 1950 when she married Elmer Sturm, a radio and T.V. repairman, though they only had 8 years together before he died, too.

After his death, Susan lived alone in the apartment above her daughter, Susan Rose. She sold real estate for a short time and also worked as a cashier in a department store for a year or two, but mostly she seemed to enjoy being at home. She and her friends formed the “Fat Ladies Club,” which consisted of them going to each other’s homes to eat and play Bunco. She was very handy and could repair many things around the house and loved to paint and wallpaper. She gardened and canned until age 80, as well as baked and cooked. When someone in the neighborhood died, Susan would bake hundreds of kolaches for the family. She was a very kind person, say her children, and she loved life, making it all the harder for them to place her in a nursing home at age 96 after she suffered a stroke. She is no longer able to speak, but her children speak for her, one of them always remaining by her side except to sleep at night, a beautiful testimony to a joyful life lived for others.

The post “If It’s God’s Will, I’ll Make It” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 5, 2015

“I’ve Lived Among Strangers All My Life”

Ludwika Janik was born in Poland on March 16, 1909 to Anton Janick and Maria Krol. She was the third of eight children and had the misfortune of looking like Maria’s mother, whom Anton hated. But the time Ludwika was three, Anton could stand the sight of her no longer, and, having other hungry mouths to feed anyway, sent Ludwika away to a Catholic orphanage in Warsaw.

Ludwika Janik was born in Poland on March 16, 1909 to Anton Janick and Maria Krol. She was the third of eight children and had the misfortune of looking like Maria’s mother, whom Anton hated. But the time Ludwika was three, Anton could stand the sight of her no longer, and, having other hungry mouths to feed anyway, sent Ludwika away to a Catholic orphanage in Warsaw.

At the orphanage, Ludwika received a sketchy education and was instead taught to work. When she turned eighteen, she was allowed to leave and “start my life,” as she puts it. Not knowing what to do, however, she decided to travel to another city where she had a friend who had been in the orphanage with her. She became depressed at her friend’s, however, despite the fact that her friend gave a party in an effort to cheer and welcome her. At the party she met a young man by the name of Boleslaw Niewiadomska, who seemed very attracted to her.

Her depression remained, however, and despite Boleslaw’s attentions, she one day found herself on a bridge overlooking the river near her friend’s flat. She contemplated jumping, but a voice told her “Don’t jump. Your life will be okay.” For Ludwika it was a profound moment and the beginning of her spiritual life. She felt overwhelmed that someone above was watching over her, that someone actually cared for her for the first time in her life. Ludwika climbed down off the ledge and married Boleslaw shortly thereafter.

The young couple lived with Boleslaw’s family and tried to find work where they could, but the marriage, even then, was not a smooth one. When Germany invaded Poland, Ludwika and Boleslaw were separated, Ludwika being sent to work in a factory.

At the end of the war, Ludwika was released from the work camp, but was alone and sick, and not knowing what else to do, decided to walk to her parent’s farm. She hadn’t seen them in years, but rather than a joyous reunion, her father demanded what she could offer for her keep. Ludwika had only her beautiful babushka that she had managed to keep hold of all through the war years. She offered it to her father, which he promptly gave to one of her sisters as a gift.

Heartbroken by yet another act of cruelty on his part, Ludwika left the farm and sought refuge from some neighbors. They gave her extra food and clothes and some cigarettes to sell in Warsaw to get her started.

She eventually made it back to Warsaw and in the end was reunited with Boleslaw, which seemed a blessing at first but which quickly soured. They traveled from city to city looking for work, never staying long enough to put down roots and make friends.

Eventually they ended up in Dansk after having two children, James and Alice. Ludwika saved and bought a sewing machine to make money as a seamstress. Though they were finally settled down, her marriage to Boleslaw grew worse. He often beat her and “abused” her in other ways until she finally left him, scraping out a small existence with her sewing and working at the local orphanage, which was very dear to her heart.

Her son, James, eventually married and immigrated to America to start a new life, and after 8 years of working, he had saved enough to send for Ludwika and Alice and his wife and child. James and his wife eventually moved to Texas, but Alice and Ludwika remained in Chicago, where Ludwika found work as a seamstress to support Alice and to put her through school.

When she retired, Ludwika says that her boss told everyone that he was going to have to hire two people to replace her. Ludwika is very proud of this and frequently relates this to the staff of the nursing home where she now lives. Her favorite thing to do at the home is to watch TV to look at the outfits and imagines how she would go about sewing them. Though sometimes melancholy, Ludwika says she doesn’t mind the nursing home, as she has, after all, “lived among strangers all my life.”

The post “I’ve Lived Among Strangers All My Life” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

October 29, 2015

“I Left the Communists to Themselves”

Vitaliy Mostovoy was born on March 12, 1946 in the Ukraine. His parents were Michael Mostovoy and Ganrietta Belodubrovskoya (which means, in part, “white oak”).

Vitaliy Mostovoy was born on March 12, 1946 in the Ukraine. His parents were Michael Mostovoy and Ganrietta Belodubrovskoya (which means, in part, “white oak”).

Michael was a Ukrainian Jew, and Ganrietta was a Polish nurse living in the Ukraine with an elderly woman she was hired to care for. As it happened, the elderly woman’s children and grandchildren often came to see her, and one day one of her grandson’s brought a friend along by the name of Michael Mostovoy. As soon as Michael saw Ganrietta, he fell in love with her, and they married in 1928. Michael worked as an economist, and Ganrietta continued working as a nurse until their first child, Ina, was born in 1932.

Fourteen years later, in 1946, a son was born – Vitaliy. Vitaliy attended high school and university, eventually becoming a professor of physics, with a specialty in medical radiation. He was on the chief of staff in this field, did extensive research and gave lectures at the university in the evenings and enjoyed his career immensely.

In 1969, when he was 23, he married the love of his life, Lyudmila. He had been dating a different girl, Anna, shortly before this and the two had gone to a friend’s apartment one night to celebrate Anna’s birthday. At the impromptu party, Vitaliy was introduced to his friend’s date, Lyudmila, and instantly fell in love with her, perhaps in the same way his father, Michael, had fallen in love with Ganrietta. Ten days after Anna’s birthday party, Vitaliy married Lyudmila in a quiet service.

Vitaliy and Lyudmila, who worked as a language teacher, made a happy life for themselves in the Ukraine and had two sons: Vadim and Anton. Vitaliy says he left the Communists to themselves and lived his own life. He felt he had a pretty good salary, a great job, a nice family and a nice apartment. When the Communists fell, however, his life began to fall apart. His salary shrank to almost nothing and his sons, just leaving university now, had no job prospects. Seeing the situation in the Ukraine as hopeless, Vitaliy decided to move the family to America and arrived in Chicago in 1994 with Vadim and his wife and daughter; Anton; and Lyudmila’s parents. And while there proved to be much more opportunity for their sons, Vitaliy and Lyudmila’s prospects worsened. Vitaliy gave up his brilliant career in research to become a janitor and Lyudmila found a job at the counter of Lord and Taylor.

After about a year in America, the powers that be at Evanston Hospital where Vitaliy worked as a janitor heard of his background in the Ukraine and offered to send him through 14 months of training to be a lab technician in exchange for him to continue working as a janitor as a volunteer. Vitaliy desperately wanted to take the offer, but eventually declined it, knowing that they could not exist for that period of time without his salary. For one thing, shortly after their arrival in America, Lyudmila’s parents began to have a myriad of health problems. Her father had to have a lung operation and his leg amputated, which required extensive hospitalization. In order to visit him every day, Lyudmila’s mother had to take three busses to get to the hospital, and eventually the stress got to her. She had a heart attack and then a series of strokes and falls before she finally died.

Vitaliy continued to work as a janitor, trying to make the best of it, comforted at least that his sons were able to have a career here. He doesn’t regret leaving the Ukraine, he says, “but I am a pessimist at heart. Wait and see.”

The post “I Left the Communists to Themselves” appeared first on Michelle Cox.