Scott Galloway's Blog, page 15

February 10, 2023

Disinflation

I’ll do approximately 25 speaking gigs in 2023, down from 47 in 2022. The primary reason for the decline is that I live in London now. Jumping on a plane to Austin to speak at SXSW used to sound fun … now it sounds like jet lag and time away from my boys, who refuse to stop growing when I’m out of town. But that’s not what this post is about. The best part of a speaking gig is the Q&A. The questions are remarkably similar across regions and events. For most of last year the most common questions were about our research on failing young men. Then they changed abruptly, to: “When will inflation come down?”

I have a degree in economics, taught micro- and macroeconomics in grad school, and worked in fixed income at Morgan Stanley. Despite that formal training, it wasn’t until I was in my forties that I appreciated that the economy is more a function of psychology and markets vs. … economics. Also, if you want to opine about the economy, you must acknowledge that nobody has a crystal ball — economists have predicted eight of the last two recessions — and be willing to get it wrong.

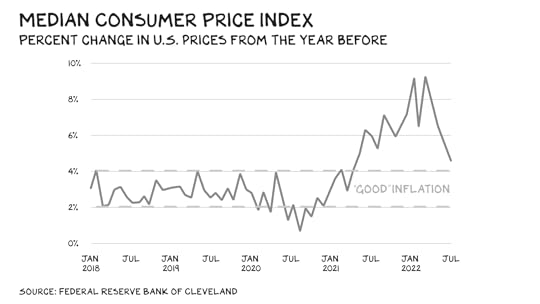

Anyway, in the third quarter of 2022 we predicted on the Prof G Markets Pod that inflation would come down as fast as it had accelerated. (I just read the last sentence and one thought runs through my head: When did I get so boring?) Wrong again. It’s going down faster. Our thinking: Inflation is a supply/demand imbalance — too many dollars chasing too few goods — filtered through our expectations of the future. And as we said six months ago, when inflation was a front-page bonfire, these factors would swiftly realign. And they subsequently have. Inflation is in fact receding, for the same basket of reasons it went up — not math, but markets. Specifically, the market of money (interest rates), the market of goods (supply chains), and the market of labor (employment). Plus, an unexpected chaser: the disruptive potential of AI.

Our thinking: Inflation is a supply/demand imbalance — too many dollars chasing too few goods — filtered through our expectations of the future. And as we said six months ago, when inflation was a front-page bonfire, these factors would swiftly realign. And they subsequently have. Inflation is in fact receding, for the same basket of reasons it went up — not math, but markets. Specifically, the market of money (interest rates), the market of goods (supply chains), and the market of labor (employment). Plus, an unexpected chaser: the disruptive potential of AI.

Some inflation is probably a good thing — too little and you risk tipping into “deflation,” which gives economists nightmares. The fear is that people will stop spending in anticipation of lower prices, and economies, like sharks, only survive in motion. In typical fashion, economists don’t agree on how much inflation is good. Many academics and institutions call for an inflation target of 3% to 4%. But central bankers in the U.S. and Europe (i.e. the Federal Reserve) target 2%. In actual business, a 100% disparity between metric targets would be cause for concern, but in economics it’s cause for tenure.

Consumers tend to worry about higher inflation more than economists, who recognize that inflation is at least partially self-correcting. When economist Danny Blanchflower (Dartmouth) was on my Prof G Podcast, he pointed out that inflation has never endured in a modern Western economy. But consumers also vote and spend, so their views carry weight. (This is 51% vibe and 49% science.) What everyone can see with their own eyes is that when inflation hits 8% in a country where it’s been sub-2% for decades, people get excited. So what happened, and why should we all keep calm and carry on?

Interest Rates (aka “This Invisible Hand”)David Foster Wallace once told a joke about two young fish who run into an older fish. The older fish says, “Morning boys, how’s the water?” The two young fish swim on for a while before one turns to the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”

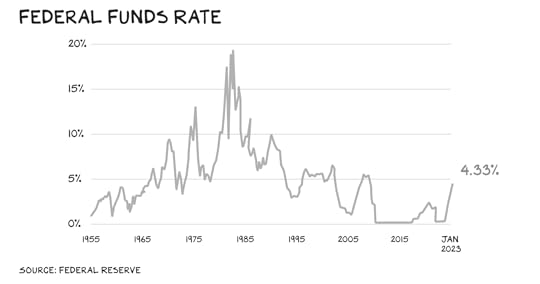

For several decades, our water has been declining interest rates. Think of interest rates as the throttle on economic risk taking. Low interest rates mean money is cheap and easy to borrow, so people take more risk. The Fed sets the floor on interest rates (the “federal funds rate”), which it took to rock bottom, Crazy Eddie “I’ve gotta move these cars today” levels to get us out of the Great Recession. Soon after the Fed finally began moving them up again, Covid knocked them back down. With the money taps gushing, the stock market ripped, as the cost to finance growth and the value of future cash flows decreased and increased, respectively. We were gamblers at a craps table crediting our resilience and daring, while the casino was pumping pure oxygen through the A/C vents.

Many strange new market phenomena emerged as a result of this new normal: Crypto, SPACs, billionaires flying to “space,” tech workers filming TikToks at their company’s kombucha bar, pet bereavement leave, car companies IPOing on zero revenue, CNBC platforming carnival barkers, VCs doing zero diligence before investing hundreds of millions of dollars in Adam Neumann (again), unprofitable tech stocks quintupling, 50-person Diversity, Equity & Inclusion departments, 30% headcount increases, Cathie Wood. We became DFW’s fish, unaware that cheap money was even a thing. But it was. Because if inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods (it is) then the free money party would eventually juice prices. There’s only so many crypto scams and boutique grocery delivery businesses we can create each day to soak up all that capital. And when prices did start to rise, the obvious response from the Fed and other central banks was to raise rates. Higher rates, less money flowing into the economy, less demand, slowing inflation. It should be that simple.

We became DFW’s fish, unaware that cheap money was even a thing. But it was. Because if inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods (it is) then the free money party would eventually juice prices. There’s only so many crypto scams and boutique grocery delivery businesses we can create each day to soak up all that capital. And when prices did start to rise, the obvious response from the Fed and other central banks was to raise rates. Higher rates, less money flowing into the economy, less demand, slowing inflation. It should be that simple.

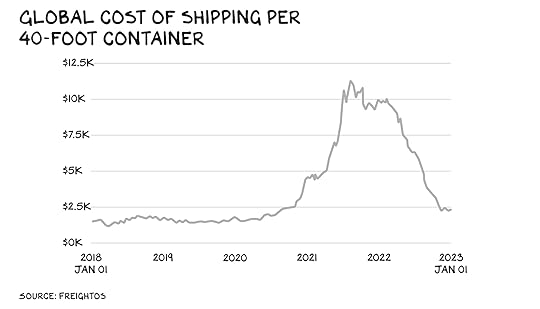

For nearly half a century, global companies had been squeezing out more and more profit by simultaneously thinning and complicating their supply chains. The Japanese pioneered “just-in-time” manufacturing, where parts and raw materials were ordered to arrive only as they were needed, rather than piling up in warehouses. Then companies from Apple to Walmart supercharged this concept globally, designing intricate webs of parts suppliers and assemblers with minimal excess capacity or inventory across the chain. It worked, but it depended on constant movement throughout the system. Which was awesome until we turned off the volcano — China and nearly every other low-cost manufacturer — in the spring of 2020. The global supply chain had become so optimized that there was no slack or ability to respond to shock. Things ground to a halt.

For a while, it felt as if half the world’s stuff had disappeared. Which it had. Covid kneecapped manufacturing’s ability to make semiconductor chips, which kneecapped tech’s ability to make … tech, and thus, anyone else’s ability to make anything else. Fewer chips meant fewer cars, printers, routers, iPads, and dog-washing machines. It wasn’t just tech. Shopping for home appliances became a SpecOps mission. Remember the baby formula shortage? Me neither. Also: lumber, toilet paper, tampons, and sofas.

By the fall of 2020, 94% of the Fortune 1000 reported supply chain disruptions, and it wasn’t just demand building. Ships were in the wrong place, some warehouses were bursting, sources of supply were coming back online at different cadences, and managers had no idea how to forecast the rate at which demand would return. Plus, China was a mess. And if the 21st century global supply chain spiderweb has a central node, it’s China. The result: All those dollars (see above) had even fewer goods to chase, so prices went up. And this is about psychology as much as reality — nothing makes people freak out about prices like empty store shelves. Retailers were snapping up any inventory they could find, and what was available for sale was sold dear. At one point, space in shipping containers was going for $277 per square foot. The cost of a house in Dallas. Only, you get to keep the house in Dallas.

Once gunked, however, ungunking was just a matter of time, and a lot of shouting over international phone lines and in stressful Zoom meetings. The entirety of the corporate world was motivated to fix these problems, and they were fixable. What remains to be seen is if we will take lessons from this debacle, and make our supply chains less brittle by investing in suppliers closer to home and becoming willing to accommodate more slack (i.e., fat) in the circulatory system. But that’s a different post.

Supply chains are almost back to normal. This is reflected in the data — the global supply chain pressure index has come down more than 75% in the past year, trade through America’s West Coast ports has risen 25% from pre-pandemic levels, and semiconductor chips are “no longer in a shortage zone.” Also, more baby formula.

Take This Job and … on Second ThoughtThe largest market is the market for time. The labor market is the market that underpins everything else; it’s where we get the money to create the demand and how we make the goods to supply it.

Once we pulled back from the drop in employment during the depths of the pandemic, there was a hot minute where labor had the upper hand over capital. That’s not the normal state of affairs — it’s called “capitalism” after all, not “laborism.” (Note: Any claim that market dynamics will sustain a middle class without massive investments is trickle down/on bullshit.) Anyway, imagine trying to explain to someone before March 2020 that large portions of the workforce would suddenly refuse to come to the office, and that they’d still … keep their jobs.

In the information economy, the balance between capital and labor likely swung too far toward labor. Wall Street bankers decided they could do Zoom meetings and proofread deal docs at Starbucks. Big Tech was particularly under the gun, offering not just larger and larger pay packages, but a raft of perks (e.g. valet parking, red-wine-braised short ribs, and free blankets), while loading up on employees — all of which created upward pressure on wage inflation.

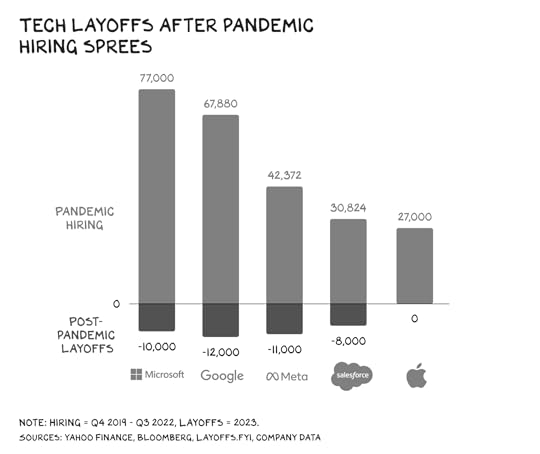

Then things changed. First, Apple added opt-in tracking to iOS, threatening the ad-supported ecosystem. Then, the impact of less free money and a return to supply chain normalcy freed up the natural business cycle, and companies (and their shareholders) realized they couldn’t keep increasing their headcount 20% each year. The balance between capital and labor in the growth economy has reverted. Tellingly, these layoffs have largely been confined to tech, a relatively small portion of the economy the media covers obsessively. Perception bests reality when headlines report a five-figure layoff every week, and nobody does the math on the broader employment picture. One of the great externalities in society is an ad-supported ecosystem that turns attention to capital, resulting in a catastrophizing of all media.

The chaser dropped on November 30, when every knowledge worker (reportedly) met their replacement: ChatGPT. With more than 30 million users, ChatGPT is arguably the fastest growing product in history. (The iPhone sold 6 million units its first year; granted, they cost $499 each and ChatGPT is free.) I used to say about WFH that if your job can be done from Boulder, it can be done from Bangalore. Well, in 2023, the new Bangalore may be ChatGPT.

Inflation is about supply, demand, and psychology, and the psychology of ChatGPT is that it may not be a good time to quit your job. Unless, of course, you’re joining an AI startup. History tells us the innovation in AI will likely create more jobs than it destroys.

Deflated OutlookLately, I’ve been struck by how negative young people are about the future. The aforementioned dark-colored glasses of the media, and legislative policy that has transferred wealth and opportunity from young to old, have broken the fundamental compact our society has had with its youth: At 30, you will be doing better than your parents when they were 30.

The poor outlook on the world young people share is understandable but not accurate. Opportunity and injustice have increased and decreased dramatically, respectively. What we lack is the leadership to ensure our immense prosperity is shared with a younger generation who have registered a wealth decline in the face of historic growth in productivity. Despite this, women in Iran, Ukrainian soldiers, and an increasingly diverse cohort of young citizens see a better future that is within their grasp and worth fighting for.

Much of the pessimism in our society stems from contrasts. Specifically the contrast between our ability to achieve the remarkable and our inability to offer the obvious. We can peer into the beginning of time, re-create the sun, and manufacture vaccines against cancer, yet the U.S. can’t seem to figure out affordable child care or housing. A nation’s well-being is correlated to prosperity that translates to progress for its citizens. Since the year I was born, China’s life expectancy has increased from 47 to 77. In the U.S., we’re long on genius but short on empathy.

Life is so rich,

P.S. If you’re a team leader, consider bringing your team to sprint together at Section4. We’ll make your team more strategic and more engaged (and give you some coaching time back). Request a demo or email teams@section4.com.

The post Disinflation appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

February 3, 2023

Luddites

Capitalism aims to convert ambition to success. Its alchemy of incentives fosters a relentless pursuit of economic opportunity from things we crave: food, shelter, bigger iPhones, desirable mates. Our hunger for wealth and love drives us to work and create — capitalism’s genius is finding new avenues for that drive.

The philosopher’s stone of capitalism is technological innovation. It’s no accident capitalism flourished and spread across the globe contemporaneously with the adoption of new technologies in production, transport, and information. Each technological advance unlocks more space for ambition — new goods, better ideas, richer experiences. And that economic expansion creates more opportunities for ambition. More wealth, more innovation … more jobs. Wash, rinse, repeat.

We relearn this lesson with every technological breakthrough. The latest is artificial intelligence, and in particular, the spectral chatbot ChatGPT. The media’s verdict on AI is already in: “We are about to lose a shit ton of jobs.” Those headlines likely inspired more clicks than “2023 Begins With Unemployment at a 50-Year Low” would have. The latter is true.

They should have interviewed William Lee. In 1589, Lee invented the stocking frame knitting machine, a device that could do the work of several workers. Queen Elizabeth I dismissed his innovation: “I have too much love for my poor people who obtain their bread by the employment of knitting to give my money to forward an invention that will tend to their ruin by depriving them of employment and thus making them beggars.” Despite the Queen’s disapproval, Lee’s design led to the mechanization of textiles, and that led to the organized attacks on textile factories by a secret society of weavers called the Luddites who destroyed every piece of machinery in sight. Parliament (by this point, all in on capitalism) made machine-breaking a capital offense and called in troops. At one point, there were more redcoats fighting Luddites at home than Napoleon in Spain.

The Luddites are gone, but we are still afraid of the machines. Wharton economist Jeremy Rifkin wrote a bestseller, The End of Work, that predicted we would have to radically restructure society, as robots would leave us with nothing productive to do. In 2014 half of workers in technology thought new technologies would be net job destroyers. Andrew Yang’s 2020 presidential campaign was predicated on this notion, and he can point to peer-reviewed research claiming that 47% of U.S. jobs are at risk of automation. Vinod Khosla, the founder of Sun Microsystems, predicted 80% of medical doctors’ jobs would disappear by 2030 due to advances in AI.

Reality BitesWhat happened? A: America has more physicians than ever before, and unemployment is near an all-time low. Even if we get an AI MD, 500 years of experience tells us there will be more jobs in health care, not fewer.

It’s not intuitive — a function of our species’ innate inability to think long term. But the reality is that disruptive technologies cause employment instability for only short periods. The market crisply reorganizes itself around the innovation, and job growth increases from there. Countless empirical studies have proven this.

A technology is introduced — say, the car — and an existing sector is made irrelevant overnight (e.g., horse and carriage). In the short term, we’re fixated on how many horses will be out of a job. Harder to imagine, however, is how many jobs the car will create — as well as the different kinds of jobs it will create. It’s hard to envision radios, turn-signal lights, motion sensors, and heated seats. Let alone NASCAR, The Italian Job, and the drive-through window. In other words, disruptive technology results in demand for things we never knew we wanted.

In 1850 farming made up 3 in 5 U.S. jobs. By 1970 that number was less than 1 in 20. From tractors to pesticides to preservatives, technological innovation was the creative destroyer that eliminated most jobs in America. But the void was filled by … everything else. Entire sectors were created that employed tens of millions of Americans.

Here we are again. ChatGPT is impressive, no doubt. “Tell me the origin story of the knitting machine.” Done. “Write a blogpost about AI in the style of Scott Galloway.” Easy. ChatGPT’s peers can also handle many other types of tasks — from digital artwork to software engineering. Together, they will likely render millions of jobs irrelevant. Why hire an artist/copywriter/coder/lawyer when you can license an AI bot for cents on the dollar?

For many companies, the process has already begun. Last week, Buzzfeed announced it would start using ChatGPT to produce content — the stock more than doubled on the news. Meta, Canva, and Shopify are leveraging the technology for their own processes. Microsoft’s bet on ChatGPT is the most significant: $10 billion.

The anxiety for the past couple decades has been over robots and automation. And it’s true that many routine, low-skilled jobs were automated away. What’s also true is that new jobs, again, filled the void. One study found that between 1999 and 2016, automated technology created roughly 23 million jobs in Europe — that’s half the increase in employment during that period. McKinsey estimates that future advances in automation will kill a third of American jobs, and that it will create more than it kills. Specifically: tech jobs, care-worker jobs, building jobs, education jobs, management jobs, and creative jobs. Net-net, technology expands employment.

Softest LandingDisruptive technology has externalities, including short-term pain for workers on the wrong side of the innovation. During the industrial revolution real wages stagnated for decades while productivity soared. This put many out of work for years, and the civil unrest that followed was understandable. Eventually wage growth caught up, but the interim was not easy. History also teaches us that America has been terrible at acknowledging the pain and allocating some of the gains from increased productivity to worker retraining and support for those affected during the transition.

We can walk and chew gum at the same time — push for technological innovation and aid the people it affects. That means generating stability (i.e. employment) in the short term while the job market recalibrates. The Ancient Greeks understood this: To offset technological unemployment (from rotary mills, gears, water clocks, etc.), Pericles started a government-funded public works program that commissioned many architectural and cultural projects and employed thousands. It also resulted in several masterpieces, including the Parthenon.

We don’t need to build temples, but we can put public money to good use: roads, infrastructure, sustainability projects, etc. I say we start with demolishing, and rebuilding, LAX and Miami International. But I digress. Jeremy Rifkin overestimated the scale of automation’s job destruction, but he wasn’t wrong about its intensity, and some of his ideas, along with those proposed more recently by Andrew Yang, merit attention. The long-term economic gains we’re bound to realize from transformative technologies (including the car, telephone, internet, and AI) should offset short-term investments in social programs and training that offer a bridge. The ROI here is not only a function of maintaining a worker’s productivity, but reducing the costs and despair that can sink a household when a family member not only loses their job, but their sense of purpose. We know technology will continue to bring prosperity. The bigger question is will it bring progress.

Life is so rich,

P.S. Want to see me lecture about TikTok live? Join the Brand Strategy Sprint starting on February 13. Enrollment closes next Tuesday.

The post Luddites appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

January 27, 2023

More Babies

Our species dates back 300,000 years. For most of that time, most humans lived to their early 30s, as a bad cut or broken bone was a death sentence. Around 1800, things changed: wealth, life expectancy, and the population all exploded. In the past two hundred years, per capita GDP has grown 15x; we now live twice as long as our great-grandparents, and our population is up eightfold — from 1 billion to 8 billion.

In 1798, Thomas Malthus predicted a global overpopulation apocalypse. It didn’t happen. When I was growing up, after a quadrupling of the population since Malthus, Paul and Anne Ehrlich penned a bestseller, The Population Bomb. The population has doubled again, but still … no apocalypse. It’s time to recognize that overpopulation isn’t a thing. It’s counterintuitive, but population density has no correlation with food insecurity. Poverty is the result of multiple factors: natural disasters, wars, poor agricultural infrastructure, and bad actors accumulating too much power. Climate change is a function of our energy and lifestyle choices, not our numbers.

We aren’t going to shrink our way out of climate change, income inequality, or any crisis. The solution is more. Specifically, more people who generate ideas that make the world more productive — ideas that let us do more with less. Stanford economist Charles Jones has shown that what generates prosperity is, ultimately, ideas — and ideas are the product of brains. More brains, more ideas.

However, we’re in danger of running out of ideas because, well … we’re running out of people.

America’s population grew 0.4% last year — a slight uptick from 2021, which recorded the lowest growth rate in our history. China’s population fell by 850,000, its first decline in more than 60 years. One Chinese official said the nation is now in an “era of negative population growth.” It’s not alone: The populations of Japan, Germany, Italy, Greece, Portugal, and many Eastern European nations are shrinking.

Throughout human history, birth outperformed death; that’s about to change. Africa’s population continues to grow, but not enough to compensate for declines elsewhere. Researchers project the global population will peak in 2064 and then begin its retreat. More than 20 nations will see their populations shrink by 50%. The greatest threat to humanity isn’t climate change or thermonuclear war, but nothingness. Specifically, that our species will decide it should slowly and steadily fade to black.

Fewer people means fewer brains and less labor — which means less innovation in solar panels and less carbon removed from the atmosphere. Also: fewer art shows, football matches, sleepaway camps, patents, proms, and bat-mitzvahs. Less of everything that makes us human. This presents a blunt and simple math problem. Globally, the number of people older than 80 is expected to increase sixfold by 2100. Meanwhile, the population of children 5 and younger will get halved. We’re facing not only a population decline, but also degradation — too many old people and not enough young people. To register the tectonic nature of this shift in our culture, imagine a world with six times as many (potential) grandparents and half as many grandkids. Thanksgiving becomes a dystopian scene from the 14th season of The Handmaid’s Tale — 12 seniors vying for the attention of the one 4-year-old.

As the population ages, it also becomes less productive. Why? Our economic productivity peaks in our 40s and declines from there.

While being less productive, seniors also consume substantially more public resources. Though seniors as a cohort control huge amounts of wealth, most of them are dependent on Social Security and Medicare — the bottom 50% of boomer households own just 2% of boomer wealth. The U.S. median household income, including Social Security, for people 65 and older is just $47,620, the lowest of any age group. As a result, we spend 40% of our total tax dollars on people 65 and up, and that will increase to 50% by 2029. Nineteen percent of our GDP is allocated to a product young people hardly consume: health care.

In the U.S., one proposal is to change the balance between workers and retirees by extending our “working age” — raising Social Security eligibility to 70, and Medicare to 67. However, the Congressional Budget Office projects that by 2035, these changes would reduce annual outlays in these programs by just 4% and 5% respectively.

Another band-aid proposal is to means-test Social Security payments. That is, cut payments for rich people. Two problems: First, we effectively do this already through taxation. (Social Security benefits are subject to tax, which takes a much bigger bite from those with other sources of income.) Second, while we could go further and strike wealthy recipients from the rolls, there aren’t enough wealthy old people to make the change worthwhile. Three-quarters of Social Security payments go to seniors who make less than $20,000 per year, and 90% go to those making less than $50,000. So net-net, we’d save … between zero and 4% of benefit payments, depending on the cut-off.

Again, we aren’t going to shrink our way out of the problem. We have to grow out of it. At a national level, there’s a real solution: immigration. Immigrants are the lifeblood of business formation in America, and they’ve been responsible for half of our unicorns. Attracting, welcoming, and retaining ambitious people from abroad is the easiest way to get rich. Like many countries, we’ve politicized the issue, as humans are wired to distrust strangers. But let’s be clear: Welcoming immigrants has always been America’s superpower, full stop.

But that still won’t be enough. We also need home-grown solutions that encourage Americans to have more kids.

Net population growth requires a fertility rate slightly greater than two births per woman. Almost every developed nation is falling short of that. America’s fertility rate is 1.8; the average for high income countries, 1.7. We need more babies — born into stable homes, with supportive families, quality health care, and good schools. What some might call a nation.

The profound, even existential question is: How do we encourage Gen Z to have kids? For starters, they’re going to have to meet one another, fall in love, and ruin their weekends (i.e., have kids). The issue is that we’re delaying marriage and starting families. Since the early 1970s, the median age for a first marriage has gone from the early 20s to nearly 30.

Eighty-four percent of women want a partner taller than them. The problem is, in several dimensions, women are getting taller and men shorter. As we’ve written before, the economic and educational gains of women over the last several decades have had an unintended consequence: Women feel there are fewer worthy men. Women value the financial capacity of a potential partner more than men do: 71% of American women say it’s “very important” for a man to support his family financially. Only 25% of men feel the same about a woman. Over the next five years, we will graduate two women from college for every man.

It’s a vicious cycle. As more women find fewer men to date, the men left behind drift from the dating scene, lose motivation, never gain social skills, and become less attractive. There are solutions: Vocational training programs, an expansion of freshman seats at colleges, and national service would all help “level up” men. We also need more “third places” where people can meet, not just to find romance, but also to build the social networks that lead to strong, durable relationships. Finally, older men need to find the time to engage in young men’s lives, as the absence of a male role model is the strongest predictor of incarceration. Put another way, if we want more men, we need older men to step up.

Creating an environment that encourages the pairing of young people is only half the problem. Our young can increasingly do math, and the math for young people and kids is increasingly ugly. Homebuyers are counseled to keep their house purchase at no more than 2.5 times their annual income, but in many major U.S. cities, spiraling prices have pushed that ratio close to 10 times. Early child care can eat up a third of a working family’s budget. Public schools are struggling in many areas, but the average private high school costs almost $16,000 per year.

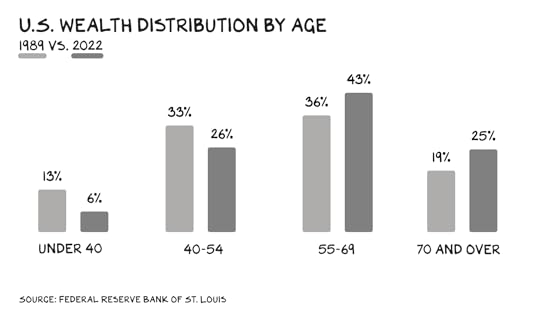

If we want more kids, we’re going to have to pay for them. The expansion of the child tax credit, to a maximum $3,600 per child for the poorest families, lifted 3 million children out of poverty in 2021. But we’ve let it lapse. It should not only be renewed, but further expanded. More broadly, we need to reverse the transfer of wealth from the young to the old. Over the past three decades people under the age of 40 have seen their share of wealth cut in half — from 13% to 6%. Taxing current income at higher rates than capital gains is theft from younger people, who make money from sweat, not investments. We have immense wealth in the U.S. — what we lack is progress.

42I had my first kid at 42. My boys are, by far, my biggest source of stress and sleepless nights. They’ve also given me purpose, and I believe they will steadily become less awful … and maybe help find solutions that help others someday. We need to make a staggering investment in younger generations to provide the means and motivation to have kids. For America, the West, and the species to prosper, we need to get serious about ruining millions of weekends.

Life is so rich,

P.S. I’m teaching a shorter version of my Brand Strategy Sprint in February: two weeks to learn how to build a sustainable, differentiated, relevant brand. Become a member to sign up. If you want a taste, you can watch the first lesson for free.

The post More Babies appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

January 20, 2023

Porn and Tanks

I moved to London six months ago. Within two weeks a fortnight the Queen died, the pound crashed, and a head of lettuce outlasted the new prime minister. Since then, I’m more struck by the similarities, vs. the differences, between New York and London. One clear distinction though: Royalty. Or more specifically, the nation’s tortured relationship with its monarchy.

Until the 20th century, monarchies were the most popular form of government. They ranged in political authority, from symbolic (constitutional monarchy) to autocratic (absolute monarchy). Hands down, the most awesome thing about monarchies were the titles: emperor, empress, king, queen, raja, khan, tsar, sultan, shah, pharaoh. I asked my youngest over breakfast if he’d mind, from this point forward, referring to me as “Khan of Marylebone.” He seemed open to it.

Besides the cool titles, however, dressing people up in crowns, gold, and silk because of who their parents were is weird. And, unsurprisingly, it makes them weird, too. Today, monarchies the world over are a museum of troubled people. While he was crown prince, the current King of Thailand appointed his pet poodle Fufu to the position of Air Chief Marshal. Princess Märtha Louise of Norway claims she can communicate with animals and angels; her celebrity shaman fiancé, who believes cancer is a choice, likely concurs. Juan Carlos I of Spain fled to Abu Dhabi after cashing $100 million in fraudulent checks. Prince Andrew is (fill in the blank).

It’s no surprise that the institution is ailing. The hereditary nature of monarchies is their most glaring comorbidity. I can prove to each of us that 99% of our children are not in the top 1%. Just as my TV career has weakened and/or killed four streaming networks (CNN+, Bloomberg Quicktakes, Vice, BBC+), an actress from the USA network may be the pathogen that kills monarchies … everywhere. Although, as the internet has pointed out, Meghan should be credited with achieving what we all aspire to accomplish: convincing our spouse their family is awful.

In today’s media landscape, where there is friction there is attention that can be monetized. Netflix paid the couple $100 million dollars to tell the tale of how a woman in her late thirties saved a prince from the horrors of Buckingham Palace. Netflix was on the better side of this deal: The show racked up 82 million viewing hours in its first week. Harry’s book, meanwhile, sold more copies in its first week than any non-Harry Potter title in history.

As a species, we can’t choose whether we worship — it’s built into us. However, we can choose what we worship. America doesn’t have royalty, so we make do with Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian. Same thing, without the crowns and community center openings. People who are famous for being famous, who have no real authority or evident talent, except an ability to capture attention and monetize it, a skill often rooted in shamelessness and an insatiable need for attention that sparks their outrageous actions/statements. Social media’s algorithms elevate the theatrics, bringing more attention to monetize, incentivizing increasingly outrageous behavior, and the wheel spins. There’s a word for this.

The “porn” cycle is why, in my view, Donald Trump was elected president and Elon Musk was, at one time, the wealthiest man in the world. Both brought a form of talent, genius in the case of Musk. But their embrace of a new medium and their knack for outrageousness and/or shamelessness built them the best brands in politics and business (for a few lettuce lifetimes, anyway). Somewhere between 49% and 51% of branding boils down to one thing: awareness (see above: famous for being famous). Harry and Meghan were willing to go where no other royals would — Royal Family dysfunction porn. The key is to be first — their antics are titillating because we haven’t seen this much detail before. Just as celebrity sex videos no longer launch careers, the book advance Bhutan’s Prince Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck would receive for a tome of shitposting his family has likely dropped dramatically.

You Had One JobEver since the Royals lost the power to govern (and frequently when they had it), the job has been to be a figurehead: Be polite, stand up for what’s right, make Britain look good, don’t say what you really think — and especially, use discretion regarding family dysfunction. Newsflash: Everyone’s family is dysfunctional, and it rarely helps to go public with the really awful stuff. Sure, dad’s affair makes for interesting conversation at Thanksgiving, but it’s likely to make the next several hundred dinners less pleasant. Shitposting your family to strangers is unnatural and destructive. For royals, discretion is more than a responsibility — it’s the entire job. The House of Windsor brand is a function of what some exceptional servants (the monarchs) have done for the past century, but it’s mostly about what the rest of the family hasn’t done.

EndangeredPrediction: We’ll never stop obsessing over celebrities, but the living anachronism of the modern monarchy won’t survive this generation. Harry & Meghan are not the first royal scandal, but they are a variant the monarchy does not have immunities for: an attractive Duke and Duchess driving Porsches to Soho House who are — at their core — porn stars.

As we’ve written about before, power is a psychological intoxicant. Any system that guarantees individuals power based on their bloodline is bound to fail — because eventually, you’re going to get a bad king/queen/prince/actress. We’re witnessing this in real time. Monarchies passed their expiration date a century ago. The grace of Queen Elizabeth was royalty’s (formidable) last line of defense. What Marx said about capitalism, that a system based on self-interest would collapse under its weight, is playing out in the Houses of Windsor and Soho.

DistractionLast week’s news about the monarchy reminds us how irrelevant they’ve become. France realized this centuries ago and separated its monarchs from their head(s), while the U.K. (more elegantly) subordinated the monarchy into a PR function. As the weapon of mass distraction that is H&M captures our gaze, more meaningful things are happening in Britain. Specifically, a government led by the democratically elected son of Indian immigrants has made an important decision.

TanksThis past Saturday, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced the U.K. is sending 14 battle tanks and 30 artillery guns to Ukraine. The U.S. has been the most prolific supporter of Ukraine thus far, contributing more military aid than every other country combined. There have been clear limits on the type of aid we’ll provide — defensive weapons, ammunition, nothing that might indicate we are in something more than a proxy war. If that sounds stupid, trust your instincts. Ian Bremmer has correctly stated that NATO is essentially at war with Russia.

The U.K.’s act is meaningful both symbolically and militarily. Fit with a 55-caliber, 47-round L30A1 tank gun, two hatch machine-guns, and a 26-liter V12 diesel engine, the Challenger 2 is one of the most formidable tanks in Britain’s (or anybody else’s) fleet. The AS-90 is a self-propelled howitzer that can fire 6 rounds per minute nearly 20 miles. Mr. Sunak sent these at real cost — the Army’s top general stated this will significantly weaken the country’s own armed forces. The U.K. also believes, however, that this serves its interest in protecting its people — to fight against tyranny, wherever and whenever it crops up.

Repeats vs. RhymesThey say that history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. Isn’t it, in fact, repeating itself? A murderous autocrat invades Europe, the West aims to avoid direct confrontation with an enemy that targets civilian centers, and the allies are drawn into a war incrementally … only to realize later their recalcitrance made things worse. The Challengers will make a difference. They’ll likely inspire Germany to send its equally impressive Leopard tanks and help Ukrainian defenses inflict further damage on Russian forces, inspiring more aid to Ukraine.

DemocracyThe need to protect democracy, the antithesis of monarchy, has never been more urgent. In the past few years we’ve witnessed democracies across the globe come under attack. There is a great deal to be hopeful about, though. Specifically: As a tyrant pushes his own people across borders into gunfire, much as another did 80 years ago, Western democracies are unifying.

The West’s response to Russia’s invasion is a historic achievement. Within hours of Putin’s tanks pouring over into Ukraine on February 24, NATO mobilized a military response. Germany, whose military policy for the past six decades has been don’t, immediately shipped Ukraine 1,000 anti-tank rockets and 3,000 small missiles. Even our financial institutions united, issuing sanctions designed to choke Russia’s central bank. Almost 12 months later, we remain resolute in our fight against Putin.

Harry and Meghan weakened monarchies last week. However, this is folly compared to the leadership Britain demonstrated this week. Porn is titillating, tanks are profound.

Life is so rich,

P.S. My Brand Strategy Sprint is back in mid-February. Watch the first lesson here, then become a member to take the full course. If you sign up by the end of January, you’ll get 25% off (see code here).

The post Porn and Tanks appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

January 13, 2023

Compete

Heraclitus, a 6th century B.C. Greek philosopher, famously said “the only constant in life is change.” He also disliked people and was depressed and irritable. He was right, on several fronts. Change is inevitable, as the cosmos has determined it’s essential. Growth and innovation are the product of change — new ideas, companies and people replacing old ones … churn.

Change brings risk to incumbents, who are incentivized to suppress it. Thus, a key role of government is to ensure efforts to suppress competition are blocked. Unfortunately, lawmakers have become addicted to expensive sleeping pills supplied by incumbents presenting a compelling offer: Here’s a shit-ton of money, and all you have to do is … nothing. Our regulators at the FTC and DOJ are stirring, but still not awake from a four-decade slumber.

As we’ve written before, yesterday’s iconoclasts pull the ladder up behind them the moment they become today’s icons. We’re in general agreement that “anti-competitive” behavior is bad, and have laws against it. Yet companies have been able to convince regulators to look the other way on an increasingly popular weapon of mass entrenchment. They’re passing out OxyContin during an AA meeting. The Oxy? Noncompete agreements.

Making good on a Biden campaign promise, the FTC has proposed a rule banning noncompetes across the board. FTC Chair Lina Khan wrote an excellent op-ed detailing why. The agency is presently seeking comments (you can do so here), so here’s mine: Word, sister.

Noncompete clauses are what firms use to sequester your human capital from competitors. When a new employee signs a noncompete with, say, Johnson & Johnson, they agree that when their employment ends, they won’t work at another pharmaceutical company for a designated period — usually one to two years. If you’re familiar with noncompetes, you likely associate them with technology jobs, where employers want to protect valuable intellectual property. And that’s the defense most often offered for the restrictions. BTW, the argument is bullshit … a confidentiality agreement does the trick.

The irony of noncompetes is they only serve to dampen growth. One of the few places where they’re banned is also home to the world’s most innovative tech economy: California. Job-hopping and seeding new acorns have been part of Silicon Valley since the beginning. In 1994 a Berkeley economist theorized that California’s ban on noncompetes was one of the main reasons Silicon Valley existed at all, and in 2005, economists at the Federal Reserve put forward statistical evidence supporting the theory. Apple, Disney, Google, Intel, Meta, Netflix, Oracle, and Tesla were able to succeed without limiting the options of their employees.

Yet outside California, corporate boardrooms love noncompetes. Historically they were attached only to high-skilled, high-paying jobs. Now they’re becoming ubiquitous across different industries at all levels. Fast-food workers are being forced to sign noncompetes, as are hairstylists and security guards. Roughly a third of minimum wage jobs in America now require such agreements. If forcing noncompetes on America’s lowest-paid workers sounds like indentured servitude, trust your instincts.

Employers claim noncompetes give them the assurance to pay for training and other investments in their employees. There is some evidence that noncompetes are associated with more worker training. But there’s a catch: They also decrease wages. The good news is we’ll train you to operate the fryer, the bad news is we won’t pay you a living wage to do it — and you can’t take a better job across the street.

The FTC estimates that noncompetes reduce employment opportunities for 30 million people and suppress wages by $300 billion per year. That’s far more than the total value of property stolen outright every year. Multiple studies also show that noncompetes reduce entrepreneurship and business formation. Which makes sense — it’s difficult to start a business when talent pools are not accessible or allocated to their best use. Downstream, the lack of competition leads to entrenchment, which eventually results in higher prices for consumers — as one study found has occurred in health care. Everybody loses. Except, of course, the incumbent’s shareholders.

Most of what gets written about business, my work included, focuses on the output. The dangers of social media, the potential of AI, or shifts in streaming. But inputs matter, too, and the most important input is our labor. It’s important because our work defines us, even more than the things we consume. Everything good in my life has come from work or relationships. The relationships, especially with my kids, have burned brighter as I can provide economic security, and it helps that Dad has a sense of self.

WanderingHowever … an increasing number of prime working-age people — men, in particular — are no longer seeking work at all. One in 9 American men aged 25 to 54 do not work today — 70 years ago that number was 1 in 50. These aren’t crypto bros who got out before the crash, or stay-at-home dads (fewer than a quarter of them have working wives). Some of the increase is accounted for by growth in the disability rolls, and by our shockingly high incarceration rate (ex-cons have a difficult time reentering the labor force), but the number of people dropping out of the workforce is much bigger than these trends explain. Often low-skilled, with job prospects that offer low compensation and lousy working conditions, they’ve simply given up.

This isn’t a uniquely American trend — in the U.K., 1 in 10 young men are economically inactive — but the decline in labor participation in the U.S. is the second largest among OECD countries. “Economically inactive” meaning not working and also not looking for work. This term should not exist in any developed society. It means our nation’s most basic and important resource lies fallow.

The FTC’s proposed ban on noncompetes includes a significant exception, one that I’ve experienced firsthand. Where the sale of a company is involved, the buyer can make a noncompete clause a condition of the sale. That’s fair: There’s often a great deal of money involved, and the employees of the acquired firm are forgoing career options in exchange for economic security. Though even a fairly negotiated noncompete is a straitjacket. When I sold my company L2 to Gartner, they required that I sign a noncompete. About three weeks later I realized I was not a cultural fit at Gartner. (The previous sentence is the mother of all understatements.) I left several million dollars on the table so I could leave before my earnout was over. But my noncompete remained in effect, and they threatened me (repeatedly) with legal action if I started anything in any near-related field. Multiplied millions of times, this creates a chilling effect in the economy; even if the legal action has no merit, raising capital for a startup under the shadow of a lawsuit is almost impossible. Sort of the mob meets blue blazers and pleated khakis.

What MattersRelationships and having a purpose (i.e., work) are the pillars of happiness. School, motivational bestsellers, and TikTok remind us we need to invest in them. But our nation also needs to invest. Last month, the U.S. invested in relationships, passing laws that (somewhat) protect your ability to love and marry who you want to. The country needs to invest in work, too, and let people decide who they want to be in a relationship with during most of their waking hours.

Life is so rich,

P.S. My Business Strategy Sprint is coming up at the end of the month. You can watch the first lesson for free here. And, hey, get 25% off membership while you’re there.

The post Compete appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

January 6, 2023

How I Got Here

I’ve been writing and speaking about higher ed for years now. Specifically, how it’s turned into a luxury good: exclusive, scarce, expensive. In 2020, it looked as if an accelerant (the pandemic) and a disruptor (technology) would change this. It hasn’t. Colleges doubled down on exclusivity. Unremarkable young Americans continue to be denied access to the best path to becoming remarkable. Making this post, which I wrote over three years ago, more relevant. That’s not a good thing.

[The following was originally published on March 15, 2019.]

State-sponsored education is who I am, and how I got here. My admittance to UCLA is singular. No other event or action has had a more positive impact on my life and the lives of people around me. Although, in light of the recent college admissions scandals, it appears I did it all wrong. I tried out for the crew team after I was admitted, and actually got my ass up at 5 a.m. six days a week so I could go move 1/8 of a shell through the water at speeds supercomputers can’t process, to nearly pass out, throw up from exhaustion, and (wait for it) keep rowing.

It’s easy to credit your character and hard work for your success, and the market for your failures. I have no such delusions. And, to be clear, I’m not modest … I believe I’m talented, maybe even in the top 1%. Yeah, BFD … that gets you entry into a room with 75 million other people (nearly the population of Germany). There are two reasons for my success: my mom’s irrational passion for my well-being and my being born in California.

PG-13 SocialismThe college admissions scandal is a small part of a revolution, in its early stages, as income inequality reaches a tipping point. Historically, when we see this type of wealth concentration, one of three correcting mechanisms takes place: war, famine, or revolution.

Parents paying ringers to take their kids’ SATs for them and coaches being bribed to claim an applicant is an athletic recruit isn’t just wrong, it’s criminal. Parents paying consultants to get their kids into college feels less bad, but it is a reflection of one of the greatest threats to our country. The middle class and capitalism are the gears that turned back Hitler and AIDS, and the lubricant for the middle class is education. We are now throwing sand in the gears of upward mobility.

For the first time, 30-year-olds are worse off than their parents were at 30. Kids aren’t getting into schools as prestigious as their parents’. For many families this is the first encounter with Technicolor inequality, where being in any cohort other than the top 1% means the leaves of opportunity are shedding prematurely from your family tree.

How many in our generation say, about the college we attended, “I couldn’t get in today”? From 2006 to 2018, the acceptance rate among the top 50 U.S. universities fell 36%, and it declined even more among the top 10 universities (60%). Stanford has an admissions rate of 4%; Harvard, 5%.

The fact that your gene pool is no longer bound for UCLA but Pepperdine feels like you’ve failed as a parent. The thrust on the fuselage for the first 10 years of a kid’s adult life is the school you did or didn’t get them into. And let’s be honest, any appraisal of a 17-year-old is an appraisal of their parents. Your son wearing your old Stanford shirt until he gets rejected and ends up at UNLV is the grist for a budding revolution where people give up on capitalism and turn to populism or PG-13 socialism.

Some numbers on admittance, cost, and the importance of college:

— 61% of high school graduates from families earning more than $100,000 a year attend a four-year university, compared to only 39% of students from families earning less than $30,000.

— 38 colleges, including five Ivies, have more students from the top 1% of the US income scale than from the bottom 60%.

— The cost to attend a four-year university has increased eight times faster than wages in the U.S.

— A master’s degree is worth an average of $1.3 million more in lifetime earnings than a high school diploma.

— Almost a third of married college grads from top schools met in college. This creates a multiplier effect for income and opportunity in that household.

Caste(ing)What happened? How did the lubricant of our prosperity become the caste(ing) of our country? There are several macro factors, as pedestrian as population growth and the increase in the number of girls attending (70% of high school valedictorians are girls), that are raising demand. But the hard truth is that much of the sand in the gears comes from a seemingly more benign source.

Just as a frog can’t detect water getting incrementally warmer, academics and school administrators have missed just how far we’ve turned up the heat on our youth. There is now more student debt than credit card debt. Young people are buying houses, getting married, and starting businesses later or never, because we’ve raised the price of our goods faster than any sector except health care.

On Monday nights last spring, I taught 160 kids who range from Marines from Athens to IT consultants from Delhi. They are impressive, good kids … looking to better themselves and, increasingly, the world. We (NYU) charge each of them more than $7,000 to take Brand Strategy, where for 12 nights, for 2 hours and 40 minutes, they get me barking at slides, and at them, about differentiation, brand identity, and Big Tech platforms. In an effort to balance the scales, I give 100% of my comp back to NYU. But for the students, that’s still about $100,000 a night in tuition, most of it financed in debt that will be on their young shoulders for a decade or more.

Seriously, what is wrong with us? We’ve lost the script and begun believing we are luxury goods, not public servants. Faculties have become drunk with the notion of exclusivity. Leaders share their pride about how impossible it is to get into our institution. We beam describing the superhuman, if not just strange, attributes of the 18-year-olds blessed with entrance this year.

Guild, in a Bad WayTenure is a guild, only more inefficient and costly. However, the workmanship is worse. It’s meant to protect academics from the dangers of provocative, original thinking (e.g. Galileo). But in my field, marketing, it’s hard to imagine anybody needs protection, as nobody is really saying anything.

Tenure, in this age, is protecting the people who need it the least. And the cost is staggering. Many universities set aside several million dollars, a reserve against any future, and expected, unproductive years for any individual they grant tenure to. Meeting someone who was recently awarded tenure is to meet them at the top of a mountain, having achieved great things to get there, and about to begin their descent.

What needs to happen:

— The U.S. needs a Marshall Plan to partner with states to dramatically increase the number of seats at state schools while decreasing the cost of four-year universities and junior colleges.

— Endowments over $1 billion should be taxed if the university doesn’t expand freshman seats at 1.5 times the rate of population growth. Harvard, MIT, and Yale have combined endowments (approximately $85 billion) greater than the GDP of many Latin American nations. If an organization is growing cash at a faster rate than the value they’re providing, they aren’t a nonprofit, but a private enterprise.

— A dean of a top-10 school needs to be a class traitor and cease new tenure grants. This would require greater comp in the short run to attract world-class academics, but productivity would skyrocket, as academics would find that the market, while a harsh arbiter, often brings out great things in people, such as competition.

— We need companies (e.g. Apple) to seize the greatest business opportunity in decades and open tuition-free universities that leverage their brand and tech expertise to create certification programs. (Apple — arts, Google — programming, and Facebook — crisis management.) The business model is to flip the model and charge businesses to recruit (shifting costs from students to firms), bypassing the cartel that is university accreditation. Apple training, certification, testing, and reporting would lead to bidding wars among their graduates — the secret sauce for any university. Higher education is a $2 trillion industry sticking its chin out to be disrupted.

In BedI’m home after traveling, and I’ve put my sons to bed. My oldest puts in his Invisalign, lies down next to me, and drifts off in my arms. I can’t help but stare at this thing that sort of looks, smells, and feels like me, but so much newer and better. Suddenly he stirs and begins to smile. He opens his eyes and tells me he and his buddies did an improv play at school and it was “hilarious.” He drifts back to sleep. He is warm, safe, loved, and next to a dad who wonders if he (like his dad) is unremarkable, but might still (like his dad) have remarkable opportunities.

In August 1982, I took a job installing shelving for $18/hour, as I’d been rejected by UCLA and had no other options for college. UCLA admission would have meant I could live at home. On September 19, 1982, I got a call from an empathetic admissions director at UCLA, nine days before classes started. She said they had reviewed my appeal, and despite my mediocre grades and SAT scores, they were letting me in, as I was “a son of a single mother and the great state of California” (no joke, her exact words).

My mom told me that as the first person from either side of the family to be admitted to college, I could now “do anything.” The upward mobility and economic security afforded me by education has resulted in a meaningful return for the state and the union (jobs created, tens of millions in taxes paid, etc.). It has also resulted in the profound: the resources to help my mom die at home (her wish) and to create a loving and secure environment for my kids.

Seats at world-class universities are a zero-sum game, full stop. When rich, uber-UN-impressive kids are admitted via fraud and bribery, a middle-class kid ends up at a lesser (or no) university, and the American Dream becomes just that, a dream. Bob Dylan said, “Money doesn’t talk, it swears.” When millionaire actors and partners in private equity firms commit fraud to take a seat from someone more deserving, it’s the rich showing the middle class their middle finger.

State-sponsored education is who I am, and how I got here.

Life is so rich,

P.S. I founded Section4 to make sure everyone could get a great business education. If you’re serious about growing in your career, education at this price is a sound investment.

We’re running a rare discount this January: 25% off for new members. Set up a free account (or, if you already have one, log back in) to get the code.

The post How I Got Here appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

December 30, 2022

2023 Predictions

Every year we make predictions. The purpose is to inspire a conversation. We also try to hold ourselves accountable. Here are some of our predictions for 2023.

2023: Patagonia Vest Recession

2023: Patagonia Vest Recession

The business story of 2022 was inflation. In 2023 it will be recession, and we’ll realize there are worse things than people with assets becoming less wealthy. In addition, a generation of tech workers (and tech journalists) who believe Pet Bereavement Leave is normal will discover a new normal. Goldman Sachs, Airtable, Adobe, Plaid, Morgan Stanley, Buzzfeed, Pepsi, Gannet, CNN, DoorDash, AMC Networks, Carvana, Nuro, Roku, Cisco, Amazon, and Asana have all announced layoffs in the past month. More than 90,000 workers in the U.S. tech sector have been let go so far in 2022 and over 150,000 globally — more than in 2021 and 2020 combined. Relative to the 5 million total U.S. jobs created in 2022, it’s a drop in the bucket, but the drop will swell in 2023. Big Tech exploded headcount during the 14-year-long sonic economic boom.

The clouds forming over Meta’s rooftop Kombucha bar: The fastest interest rate hikes in history; tech valuations reuniting with fundamentals; and Musk proving that a business can maintain a minimally viable product with a third of its employee base. Twitter’s revenue has collapsed, from $5 billion to $1 billion, but that’s more a self-inflicted wound than the result of Musk’s mass firings. Overheard in every tech boardroom: “We can have the same great taste (massive reduction in headcount/costs) with fewer calories (revenue loss).” The most consequential business strategy of 2023 won’t be AI or supply chain diversification, but being tough without being an asshole.

The average U.S. tech worker is 35, meaning they were in 8th grade in 2001 and in college in 2008. The longest expansion in America’s history is “normal” to them — it’s the only market they know. The layoffs will make for dramatic headlines as journalists, most of whom have likewise only reported during high tide, broadcast history’s largest symphony of tiny violins. The upside(s) of the reckoning (aka, capitalism) will be substantial. Specifically …

Amazon, Alphabet, and Meta Register Historic Profits

Layoffs are bad for company morale and worse for those who get fired, but they’re often good for business. The average tech worker cost their employer at least $100,000 in salary plus benefits and dilution in 2022. Call it $150,000. Fewer humans means substantially more profit per share. Google and Meta, with 30% operating margins, can either fire 25,000 people each or increase their top-line revenue by $12.5 billion and register the same operating income. They, and hundreds of other tech firms, will choose a version of the former.

Activist shareholders, and management whose lifestyles are linked to the share price, realize this. TCI, a hedge fund with $6 billion of Alphabet shares, sent a letter to CEO Sundar Pichai last month saying the company has too many employees. Alphabet and others will heed TCI’s call. Despite the headwinds facing the ad giants, including Apple’s privacy measures, the rise of TikTok, and a slowing economy, “efficiencies” will deliver Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta’s most profitable quarters ever.

As a founder/entrepreneur I’ve had several decent/good exits. The skills responsible for my (modest) success, other than being ridiculously fucking lucky: communication, attracting talent, and firing (non)talent. Put another way, if you enjoy the Hallmark Channel more than the History Channel … don’t start a business. If this sounds callous, keep in mind that 99% of the world would kill to be a recently laid-off U.S. tech professional; it means you are educated, highly skilled, and live in a democracy. And this downsizing cloud comes with a thick silver lining — a recession is the best time to start a company, because people and equipment are less expensive and consumers/clients are open to new products/services.

ByteDance Breaches $1 Trillion in Value

A couple months ago we wrote about the two forces sucking the oxygen from the advertising ecosystem: Apple and TikTok. Apple is already a multi-trillion-dollar firm, and TikTok will cut the ribbon on its four-comma valuation this year. At its current $300 billion valuation, TikTok’s parent, ByteDance, is worth more than Disney, Snap, Pinterest, Twitter, IPG, WPP, and the Omnicom Group combined.

The Chinese company took just five years to reach a billion users — three years less than Instagram and four years less than Facebook — and those users spend 100 minutes/day on the platform. When young people are asked to choose between TikTok and all of TV/streaming … they choose TikTok. Think about the last sentence. ByteDance’s network should be banned or spun to U.S. interests, but that’s another post. The parties involved will find an accommodation, as there’s just too much money at stake.

Nearly 7 billion of the 8 billion people on Earth identify with a religion. As a species, we can’t choose if we worship, but can choose who we worship. As search engines and iPhones replace mythical and spiritual beings as our sources of truth, our worship shifts to the gods responsible — the wealthiest person in tech has a 1 in 3 chance of being Time’s Person of the Year. Our new gods: Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Larry and Sergey, Elon Musk, Elizabeth Holmes, Sam Bankman-Fried …

Our gross, nonsensical adoration of tech innovators may have peaked. It’s been a tough couple of months for the Church of Technology: Elizabeth Holmes was sentenced to 11 years, and her colleague to 13 years; Nikola founder Trevor Milton was convicted of fraud; Celsius Network went bankrupt and faces federal investigations; and SBF’s Oops I Did it Again apology tour was cut short due to an outbreak of law.

I hope a fresh round of bankruptcies, margin calls, and orange jumpsuits dethrones our modern-day gods and sobers up the media, the public, and elected leaders who worship them. I’m optimistic these abusers will not just be reassigned to different parishes, but their close-up will illuminate the importance of regulation, trust, and independent boards. We may even realize the people responsible for prosecuting fraudulent actors, maintaining backstops on savings accounts, and writing laws are the people who are really on y(our) side.

I also believe we’ll see a return to 20th century admiration for government agencies and people who have re-created the sun and are transporting us to the beginning of time. They have achieved these things without stealing from others, accusing ex-employees of sex crimes, or spreading homophobic conspiracy theories.

While we’re here …

Tesla: Record Revenue … and the Stock Halves (again)

Scott Fitzgerald defined intelligence as the ability to hold two opposite ideas in the mind at the same time. Tesla will post record revenue and deliveries next year, and the stock will still get cut in half. I’ve been a Tesla bear for a long time, which means I’ve been (very) wrong for a long time. The lesson was to “never bet against a company with a great product.” And that’s still true. The problem for Tesla is that greatness is relative, and the industry is catching up. In London every other car is an EV, and most of them aren’t Teslas. At the World Cup in Qatar there was a barrage of advertisements for the Ioniq 5, Car and Driver’s 2022 EV of the Year.

Tesla pulled the future forward with EVs that bested internal combustion cars. But the future is finally here, and TSLA is catching up to our prediction. Last year we said (again) that Tesla would be cut in half in 2021, and it was. The slide will continue. Why? Tesla still trades at 35 times earnings, while the competition (something Tesla didn’t have before) trades at 5 times earnings.

I believe the best-performing large tech stocks of 2023 will be Airbnb and Meta. For different reasons. Airbnb stock is pricier, but we believe it will grow into its valuation. Seventy percent of the company’s site traffic comes from direct, organic visits — that’s compared to 40% for Marriott and Expedia. This brand strength results in a net margin twice those of its hospitality peers. Airbnb also generates half a million in revenue per employee, more than most tech companies — and ten times greater than hotel chains. The company can reinvest at a rate that will further increase the delta between the business and its peers. I believe, already, that ABNB is the strongest hospitality brand in modern history. “I got a Hilton in Los Angeles,” said nobody, ever.

I hate Meta and … its equity will outperform the market. The Zuck’s growth plan (the metaverse) is something his most formidable enemy could not have dreamt. We said this before it was cool, and the market concurred this year and took the stock down 75%. In one year, Meta lost its gains from the previous five. Sure, the metaverse is dumb/stupid/ridiculous, but Meta is still a $120 billion business and a cash volcano with (despite Zuck roofieing his colleagues with a Big Gulp Grande Venti ayahuasca trip to the metaverse) exceptional operating margins. Facebook and IG are no longer the hot new thing, but the population of the Southern Hemisphere and India still use them.

Other strong performers will be Chinese tech stocks such as Meituan, Pinduoduo, Tencent, Alibaba, and JD.com. The thesis is simple: On an enterprise-value-to-revenue basis, these stocks are selling for 50% off their U.S. peers due to political uncertainty, not the performance of the underlying businesses. There’s likely more short-term turbulence as China reels from its abandonment of “zero-Covid,” but China’s economic heft and Xi’s need to continue bringing his countrymen into the middle class will augur a reprieve for the tech sector.

Longshot: Disney Acquires Roblox

Roblox is a metaverse that works. The gaming platform has roughly 60 million daily active users, half of them 13 years old or younger. At the beginning of the year the stock was $120; it’s now below $40. At Disney, Bob 1 is back, and he may be the best buyer in history. During his first stint he acquired Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, Bamtech, and 21st Century Fox. (We’ll ignore the last one.) Acquiring Roblox would be expensive, but Disney has the capital, and strategically it makes sense. Just as Bob brought Woody and Anakin Skywalker to the parks, he has the opportunity to now bring the parks (and their characters) to Roblox. A Disneyverse, if you will.

Consolidation of Subscale

Bear markets morph large firms into firms that are not large enough. These are prime acquisition fodder. I believe we’ll see the consolidation of many subscale companies, including Lyft, AMC, Peloton, Carvana, and Robinhood. In terms of market cap, Uber is now 15 times more valuable than Lyft, as are Ford and GM, who are hungry for autonomous driving experience and IP. Expect many acquisition attempts this year, accompanied by headlines that the FTC is “reviewing it.”

2023 Tech of the Year: AI

Like Web3 last year, artificial intelligence is on track to be the most hyped technology of 2023. Unlike Web3, however, AI will (mostly) live up to the hype. We’ve already witnessed the immense capabilities of image- and text-generating AI programs, including Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and ChatGPT. I wrote a post a few weeks ago showcasing the expansion of AI capabilities. An influx of capital and attention in 2023 will accelerate the category’s growth.

Streaming Consolidates

The past decade in streaming has been a nonstop champagne-and-cocaine party where the numerical direction of content budgets, deal sizes, and stock prices was up and to the right. Until this year. Since December 2021, Netflix’s stock price is off 60%, bringing the rest of the streaming market down with it. For consumers, there are too many choices — both in terms of platforms (the average U.S. household now uses five streaming services) and programming (the average Netflix user spends 18 minutes searching for something new to watch). The space has gotten too crowded, and it will tighten.

As in tech, activist investors will rattle media cages. I’d bet Warner Brothers Discovery is put in play by the end of the year. HBO remains the premier artisanal content creator — garnering nearly three times the Emmys per dollar spent than Netflix, and four times as many as newcomer Apple. It’s a crown jewel in search of a suitable crown.

The Situation Room and Tucker Carlson are incentivized to tell us “America is awful, news at 11.” Their apocalyptic vision is misguided, bordering on delusional, as we are in a position of strength relative to our global peers: Over the past two years our stock market has outperformed China’s by 30%. Our inflation rate, while high, is nowhere near those of European nations including Germany (10%+), the U.K. (11%+), and Italy (12%+). We are energy and food independent and have again demonstrated our mastery of the world’s master: technology (see above: re-creating the sun). Nobody is lining up for Chinese or Russian vaccines. The U.S. has pledged $47 billion in military aid to Ukraine, greater than the combined contribution of every other country.

Aid to Ukraine will be the best trade of 2023. For only 6% of our defense budget we continue to repel an enemy and signal to the world the United States of America is (again) an ally without equal. As Elton John reminds us on his seventh “Farewell” tour: The bitch is back.

2023I hope 2023 brings you health, prosperity, time with loved ones, and the presence to appreciate all three.

Life is so rich,

P.S. I’m teaching the Business Strategy Sprint again in January. If you want a taste before becoming a member, you can watch the first lesson here.

The post 2023 Predictions appeared first on No Mercy / No Malice.

December 16, 2022

2022 Predictions Review

Every year we make predictions for the coming year. We try to get them right, but the real objective is to catalyze a conversation. As I am not the Dark Prince or an alien (either would be fun to roll with in Vegas) I get some right/wrong.

Anway, we’ll be publishing our 2023 predictions in a couple weeks. But first: accountability. Let’s review our 2022 predictions to see what we got right, sort of right, wrong, and … completely wrong. Keep in mind, these auguries were expectorated pre-Ukraine, pre-Elon/Twitter, pre-inflation, pre-a mess of things. Our review below. TL;DR: It was another strong year of predictions.

Champagne and cocaine for the dawg. We posited that the lofty valuations of growth-y tech stocks and meme stocks, or “story stocks,” would be taken down dramatically (i.e. rationalized). In particular: EV stocks Tesla, Lucid, and Rivian would get cut in half (correct), and AMC and Gamestop would trade below $10 (correct, incorrect). Big Tech gave back the GDP of India. I wrote that 2021 was “the year of the bubble.” 2022, we predicted, would be “the year of the pop.” OK, that’s it for our review … enjoy 2023.

Anyway, this correction is healthy. A pre-revenue car company that commands a market capitalization greater than BMW and General Motors (combined) is just plain farfegnügen. My biggest holding, ABNB, is off 48%. I did eat my own cooking (sort of) and have been writing covered calls for the past 18 months, which cut my losses in half. Note: I’m always in the market, as nobody can consistently predict the market. Anyway.

The Zuckerverse Fails

This was a layup. A basic truth: The cosmos doesn’t want any one organization or person to consolidate all power. There has never been a president of the world, and the richest man controls just 0.04% of the planet’s wealth. The safety mechanism is that power corrupts and makes you stupid. You begin believing that you should spend $45 billion on a micro-blogging platform to spread conspiracy theories, or that people want to spend time in a legless universe. The notion of attaching 3 pounds of plastic to your head to get nausea and a face rash in exchange for a low-resolution, boring, shittier version of reality is just plain stupid. We predicted Zuckerberg’s metaverse would be “the biggest tech flop of the decade.” Meta continues to spend/lose $1 billion a month on Reality Labs.

My idea: Instead, spend the money on employee retention, and every workday at HQ raffle off an Airbus A380 (resale value: $50 million) to a lucky employee. Same cost. Think about that.

Or: Give $5,000 a month to each active user.

Or: Pay the entire cost of attendance for every undergrad in the University of Texas and California systems.

Or: Give away 500 Porsches, 500 Ferraris, 600 racehorses, 700 Harleys, 10 Gulfstreams, an Airbus A380 each month and then roll/ride/gallop/fly to Burning Man, where you set ablaze a stack of benjamins the height of the Statue of Liberty. (No, really, I did the math.)

The places Meta employees could go … on this awesome place called Earth. Instead of venturing to a fucked-up alternative reality brought to you by a man-child with aspirations of being a scientific god who pelts you with Nissan ads and now needs security stationed on each end of his block. Too much?

Meta’s Horizon Worlds is garnering roughly 200,000 monthly active users, which is 300,000 short of its end-of-year target and 2.5 million short of social media relic MySpace. Meanwhile, only 9% of the worlds created by users are visited by more than 50 people, and more than half the headsets aren’t in use six months post-purchase. Anyway, the metaverse as a topic of interest has gone stale. As measured by Google search volume, people are six times more interested in Crocs.

OK, we know what happened … sick of talking about it.

Frances Haugen Is Time’s Person of the Year

I predicted (hoped) that the world would give Frances Haugen the credit she deserved for blowing the whistle on the rage machine that is Facebook — and that this might be reflected in the form of a Time Person of the Year award. Instead, 72 hours later, the award went to Elon Musk. Confirmation that our idolatry of innovators is worsening, as we increasingly treat billionaire tech founders not as influencers or even heroes, but gods whose bigotry and idiocy are just more genius waiting to be revealed.

Web3 Is the New Yogababble