Ikram Hawramani's Blog, page 42

April 22, 2019

Is celebrating 15 of Shaban (Barat) a bida?

What is your opinion on Shab e Barat? Some say it is bidah some say it's not

Regarding all supposedly bidʿa acts of worship I believe Ibn Taymiyyah has the most sensible opinion (unfortunately most of those who claim to follow him do not take the trouble to read him carefully). His opinion is this:

Those who sincerely perform the act of worship, believing that they are doing a good deed, may be greatly rewarded by God for it.Those who are not convinced that the act of worship is legitimate should avoid it.

Personally I am in the second camp; I am not a fan of most of these forms of worship and avoid them. But I do not criticize those take pleasure and satisfaction in them. It is their business and God may reward them for their effort and sincerity.

For more on Ibn Taymiyya see my essay Ibn Taymiyya and His Times.

What do Muslims think of non-Muslims?

As salamu alaikum wa rahmatullah. Would you kindly explain to me how the religious Muslims think that people other than them are apostates or infidels? I'm a Muslim, but I find this rather rude and unpleasing. If Muslims were given some kind of ability to shift perspective with them, I doubt the Muslims would want to learn to understand their viewpoints. This is something that I cannot fathom.

Alaikumassalam wa rahmatullah wa barakatuh,

Please see the articles on the page Non-Muslims in Islam where I answer your questions in detail. If you have further questions please feel free to submit a new one.

Why We Should Stop Using the Word “Islamophobia”

Recently the British philosopher Roger Scruton was sacked from his government position for stating in an interview that Islamophobia is a propaganda word “invented by the Muslim Brotherhood”, among other statements. The interview was intentionally redacted by the journalist to put Scruton in the worst light possible. Since then the journalist has disappeared from social media after refusing to release the full tape of the interview.

Roger Scruton

Roger ScrutonThe treatment that Scruton has received is typical. He has dared to sin against what the Western zeitgeist considers sacrosanct. There is no forgiveness possible, and he is given no opportunity to justify himself. The zeitgeist is his judge, jury and executioner, and there is no appeal possible. Scruton has been unpersoned; he is considered to be no longer a human and to not deserve to be treated with human decency.

This is especially sad because Scruton has been one of the very few Western intellectuals who has tried to engage with Muslim intellectuals. Second-rate intellectuals like Jordan Peterson are happy to regurgitate 19th century Orientalist theories about Islam without bothering to actually read a recent scholarly book or two on the religion. The great progress that the Western study of Islam has made in the past few decades has completely passed them by. Scruton, however, has been willing to sit with intellectuals like Hamza Yusuf in dialog. He also has a close relationship with a hijabi Syrian lady trying to rebuild Syria’s destroyed architecture. Scruton has been one of the very few intellectuals willing to treat Muslims as humans rather than as second-class humans to be shunned.

While Scruton’s views on Islam do not always hit the mark, we should acknowledge that he has done far more than others to try to engage with it and understand it. He should be celebrated for this and whatever erroneous statement he makes should easily be forgiven. So even if what he had said about Islamophobia had been unacceptable, it should still be the easiest thing in the world to continue to consider him a respectable intellectual and thinker and to continue to engage in dialog with him.

But the truth is that his view of the term “Islamophobia” hits the mark.

The problem with “Islamophobia”

According to the New World Encyclopedia,

The term phobia, from the Greek φόβος meaning "fear," is a strong, persistent, and irrational fear or anxiety of certain situations, objects, activities, or persons. A phobia disorder is defined by an excessive, unreasonable desire to avoid the feared subject. Phobias are generally believed to emerge following highly traumatic experiences.

"Phobia", The New World Encyclopedia.

According to this definition of phobia, Islamophobia is an irrational and unreasonable fear or anxiety about Islam.

For a politically-minded person, Islamophobia is a very useful word (similar to homophobia and other modern, politically-instituted “phobias”). It helps insinuate that a person who criticizes or dislikes the object under question is irrational and unreasonable. It helps identify a group of humans as irrational and unreasonable, and in this way helps justify demeaning and dehumanizing them and their concerns.

Islamophobia makes dialog impossible. If you fear Islam, you are the problem, not Islam. It discards the subjective experience of those who fear or dislike Islam while promoting an authoritarian ideology that accepts nothing less than full submission to a positive view of Islam as the only option for a reasonable and rational human.

Making Islamophobia sound like a reasonable word may seem like a great accomplishment for a politically-minded Muslim. It helps create an easy-to-use framework for attacking anyone who expresses criticism of Islam. Calling them an “Islamophobe” automatically suggests that the attacked person is irrational and unreasonable. Whatever concerns or criticisms they have are worthless. And not only that, the politicization of the word also helps take this attack further, making it an attack on their basic humanity. An Islamophobe is not a person with human rights, they are an irrational and insane unperson who should not be treated like a human.

But what do we gain by using this slur against people? It does not change anyone’s mind about Islam. It only helps drive their opinions underground, so that they start to feel that there is an oppressive system above them that prevents them from freely voicing their opinions. Islam restricts their freedom of speech so that the only places where they can voice their opinions become Internet forums and YouTube comment sections.

By forcing criticism of Islam and Muslims to go underground, we only help it grow. Not only do these people hold on to their former opinions, they feel encouraged to only become more extreme because of the feeling that their opinions and their humanity are discarded from the start by Muslims.

The rationality of fearing Islam

Islamophobia implies that it is irrational to fear Islam. This sounds frankly idiotic to someone who feels that the evidence is all around them for why they should fear Islam. Terrorist attack after terrorist attack reinforces the view that Islam is a danger to society. Documentaries are constantly published about the suffering of women under Sharia courts in Pakistan or Britain.

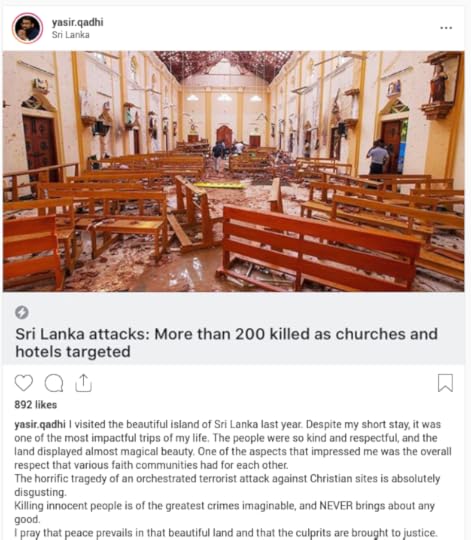

The disgust that our Muslim intellectuals at terrorist attacks does not help remove the association between Islam and terrorism for the simple reason that most people do not get to see the statements of these intellectuals.

The first step to dealing with the fear of Islam in the West is to acknowledge that this fear is rational. Within the subjective experience of the Western person who is exposed to images of terrorism and abuse of women, it is perfectly rational to conclude that Islam is a source of these evils. Calling them irrational is only taken by them as an insult and a slur. Islamophobia tells them that if they make the rational connection between Islam and terrorism, that they are doing something wrong. But they know perfectly well that they are rational, so the insult does nothing to prevent them from making such a connection. It only reinforces their view actually, because they start to sense that there is an Orwellian force from above that wants them to throw away their rationality for a new, politically-instituted faux rationality that somehow finds it logical not to connect Islam with terrorism and other negative things.

It is perfectly rational for a person to fear or dislike Islam based on the information that they are exposed to everyday. The problem is not with the rationality of these people. The problem is with the information that they are exposed to. Discounting these people’s subjective experience is a most futile exercise. The rational conclusion based on the information that they are exposed to is that Islam is a problem. If we want people to stop making this conclusion, we cannot do it by attacking their rationality, but by changing the information.

The information received by a Westerner about Islam is partly true and partly made up of prejudices. The true part consists of the news of terrorist attacks and articles and documentaries about the suffering of women and women’s rights activists among Muslims. The right course of action is not to attack people who bring such information to people’s minds when it is done with journalistic integrity. The right course is to remove the causes for such information being created in the first place by working to promote a tolerant and civilized Islam that naturally prevents terrorism, the abuse of women and all other incentives for the creation of negative information about Islam.

Humanizing the “Islamophobe”

The way to convincing a person who has a negative view of Islam that their view is wrong or imperfect is not to dehumanize them by calling them an Islamophobe, but by treating them as complete humans equal to ourselves.

Kant’s moral philosophy teaches us that the only proper way to treat a fellow human is to treat them as “ends” rather than “means”. Every human is endowed with infinite worth and inviolable dignity from the moment they are born. This is a moral right possessed by all humans, and breaking it by dehumanizing those we dislike only reflects negatively on ourselves. Breaking Kant’s categorical imperative to treat humans as infinitely worthy proves that we are willing to dehumanize some humans. We do not believe in universal human rights and arrogantly think that we can be judge, jury and executioner against humans we dislike.

So how do we treat someone who fears or dislikes Islam? By treating them as if they have every right to come to their own conclusions about Islam. When a Muslim treats a person who dislikes Islam as if the person has infinite worth and dignity, the result is that the person ends up seeing an aspect of Islam that they did not see before.

Good and evil are not equal. Repel evil with good, and the person who was your enemy becomes like an intimate friend.

But none will attain it except those who persevere, and none will attain it except the very fortunate.

The Quran, verses 41:34-35.

Whenever we treat a person who dislikes Islam as less than ourselves, we are showing them that we are willing to discard their inviolable dignity for the sake of our desire for power and comfort. Sensing that we dehumanize them, they will only feel justified in further dehumanizing us. This creates a positive feedback loop that only increases the radicalization of both sides so that we end up with angry and intolerant Muslims who accept nothing but submission to a positive view of Islam from others, and angry and intolerant dislikers of Islam who feel fully justified in working to further increase people’s negative view of Islam by writing or sharing information on Islam’s negative aspects.

This is not how civilized people should behave. By treating critics of Islam with the utmost respect and consideration (regardless of whether they treat us the same way), we show that we follow a higher, better and more civilized morality and in this way prove that we are worthy of being engaged with intellectually. We should display kindness and consideration to critics of Islam, not out of an attempt to manipulate them, but because that is the type of people we are.

A Muslim imam’s preaching for respect and tolerance sounds rather hollow when they are willing to dehumanize people by calling them Islamophobes. An Islamphobe is a person, and persons have the right to be treated the way we like to be treated ourselves (Kant’s categorical imperative). By calling them Islamophobes we break the first rule of morality when it comes to our fellow humans. Nothing we say after that will have any force or meaning. We have started by dehumanizing those who dislike us.

Conclusion

If Islam truly makes us moral and civilized, this should first of all things come out in our actions and words. By using “Islamophobia” we break the first rule of moral and civilized treatment of others, in this way showing ourselves to be rather immoral and uncivilized. We make dialog impossible by calling critics of Islam irrational. If they are intrinsically irrational, then no conclusion they can reach is valid. If we make it a condition for them to like Islam before we consider them rational, then we are basically telling them to sell their independence of mind and conscience to us so that they can become fully human.

Rather than using Islamophobia to dehumanize our opponents, we should make every effort in the opposite direction, constantly showing them that we continue to see them as respected and dignified humans regardless of what conclusions they have reached. They are humans whose subjective experience has made them develop a negative view of Islam based on the information they have received. We do not fix this situation by putting the guilt on them and their rationality, but by showing them that there is a problem with the information.

If as a Muslim you cannot see an “Islamophobe” as an equal human, then you have not learned the first lesson of morality.

April 21, 2019

Who decides if a hadith is authentic or not?

Salamalaikum, could you please give a layperson like me an understanding of how the hadiths are classed. I see terms like sahih for Bukhari and Muslim, but then there are others that are also considered sahih but are not listed in Bukhari and Muslim. What is hasan? what is daeef(sp?)? and who determines the lesser known hadiths are sahih or hasan? Is that a majority opinion? Jazakallah khairun

Alaikumassalam wa rahmatullah,

Sahih al-Bukhari and Muslim are simply two handbooks written for legal scholars. They bring together authentic hadiths that are useful for a legal scholar to know. They are not meant to be complete encyclopedias of hadith. All hadith scholars are qualified to determine the authenticity of hadiths. Al-Bukhari and Muslim are just better known than the others. Each hadith scholar can make their own sahih collection, for example there is Sahih Ibn Hibban.

The word ṣaḥīḥ refers to a hadith that has a good enough quality (text and chain of narrators) to be considered very likely to be truly from the Prophet PBUH.

The word ḥasan refers to a hadith that is not good enough to be considered ṣaḥīḥ (it may have some half-trustworthy transmitters), but it is considered good enough to be considered possibly authentic.

A ḍaʿīf (”weak”) hadith is one that comes from untrustworthy transmitters so it is considered likely to be false/fabricated.

Islamic Law and Jurisprudence: Studies in Honor of Farhat J. Ziadeh

Get it on Amazon

Get it on AmazonIslamic Law and Jurisprudence: Studies in Honor of Farhat J. Ziadeh (published 1990) is a collection of papers written in honor of the Palestinian-American professor Farhat Jacob Ziadeh (1917-2016), founder and first chairman of the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization at the University of Washington.

I bought this book after seeing it cited in Omar Farahat’s 2019 book The Foundation of Norms in Islamic Jurisprudence and Theology and finding it for sale for only $6 on Amazon.com, without looking into the book’s contributors. I was therefore pleasantly surprised to find that it had articles by some of the best scholars of Islamic studies in the late 20th century: Wael Hallaq, George Makdisi, his son John Makdisi, and Bernard Weiss.

The first article is by Wael Hallaq and studies the problem of inductive corroboration in Islamic legal reasoning. How many witnesses are required to prove a point beyond doubt? Hallaq studies the issue of the mutawātir report (a hadith report that is transmitted by so many people that a person can be completely sure of its authenticity). Some scholars fixed the number for establishing tawātur at five witnesses, while others chose 12, 20, 40, 70 or 313. But during the tenth and eleventh centuries, the dominant view emerged that only God knows how many witnesses would be required for tawātur.

The opposite of a mutawātir report is an āḥād (“singular”) report; a report that does not come from a sufficient number of transmitters to establish certainty. Hallaq argues that according to the jurists, an āḥād report had a probability of authenticity of less than 1 (i.e. less than 100%) but higher than 0.5 (50%). By the mere fact of a report having an unbroken chain of transmitters to the Prophet PBUH, it was considered more likely to be authentic than not. And when two singular reports support a particular point or issue, the probability increases.

In my essay Mathematical Hadith Verification: A Guide to the New Science of Probabilistic Hadith Transmitter Criticism I propose a way of formalizing these probabilities. But unlike the jurists, I treat the probability of the reliability of each transmitter independently. Each transmitter is given the benefit of the doubt by being considered as 60% likely to be truthful and accurate. But when more transmitters are added to a chain, their probabilities are combined, lowering the integrity of the information transmitted.

The second article is by Jeanette Wakin of Columbia University (d. 1998) and focuses on the views of the Ḥanbalī scholar Ibn Qudāma (d. 1223) regarding interpreting divine commands. When God tells us in the Quran to do something, does this imply permission, recommendation or obligation? In verse 5:2, God tells us, “when you leave the state of iḥrām, then hunt.” Interpreting this command as implying obligation means that every pilgrim is obligated to go hunting after they are done with the rituals of the pilgrimage to Mecca. But of course, it is widely known that hunting is not obligatory; so the command must only imply permission. While jurists like al-Ghazālī adopted the moderate view that divine commands cannot be interpreted as permission, recommendation or obligation unless we can find out more information about the command (for example in the Prophet’s traditions PBUH), Ibn Qudāma’s view was that all commands imply obligation unless proven otherwise, except in the case of a command that comes after a prohibition, in which case the command only implies permission (as in the hunting example above).

Bernard Weiss’s article is on the problem of objectivity in Islamic law. How can objectivity be ensured in the interpretation of the law? Do the differences among scholars on matters of law imply a lack of objectivity? Weiss argues that the jurist’s performance of ijtihād (of re-analyzing the sources of the law and reaching new decisions) is how objectivity is ensured within our human limitations. Studying revelation (the Quran and the Sunna, i.e. the Prophet’s words and actions) always has a chance of leading to new results. But in order to have practical law, we must be able to establish an end to this process, otherwise we will never reach a conclusion; we will always be suffering the uncertainty that better knowledge and understanding will lead to different results.

The process of ijtihād solves this dilemma by giving a qualified jurist the right to do his own independent research until he reaches a point when he can in all honesty say that he has done his best with what is available. At that point he can issue a ruling that will be considered objective and applicable for himself and his followers. The process of ijtihād therefore leads to a historically-limited instance of objectivity; the best objectivity that can be had within our human limitations. And when each jurist performs this through time, we get a historical series of objectivities, each presumably better than that which preceded it.

Farhat J. Ziadeh’s article is on the issue of ʿadāla (“justice” or “justness”), the quality of a witness being considered reliable and trustworthy by an Islamic court. He mentions the interesting anecdote of a man who refused to pay the voluntary separation gift that a man owes to his divorced wife. The judge who presided over the separation later refused to accept the man as a reliable witness in a different case because the man had refused to be charitable and God-fearing in the previous case. Another interesting anecdote is that al-Ḥakam I (d. 822 CE), a ruler of Umayyad Spain, was rejected as a reliable witness by a judge that he himself had appointed.

Ziadeh argues that Islam led to a transformation of the Arab ideals of virtue. In the pre-Islamic era, virtue was a warrior’s courage, a rich person’s generosity, and the dedication to keeping one’s word even at the cost of losing a loved one. But in the civilized atmosphere of the Islamic city, the virtues were those qualities that enabled the law to function properly.

The fifth article is by David F. Forte, a law professor at Cleveland State University. He tries to clarify the Islamic principles of property rights by studying how Islamic law deals with the issue of lost property. He concludes that Islamic law is more concerned with the rights of a property owner than the English common law.

George Makdisi’s article is going to be of the most interest to Western readers. He defends his thesis, that he has defended in many other places, that Islam created the concepts of professor, doctoral dissertation and academic freedom.

Since Islam lacks an ecclesiastical hierarchy that can decide issues of orthodoxy, the only way to ensure arrival at consensus in a legitimate way was to adopt academic freedom. A legitimate fatwā in Islam is one that is given by a professor who enjoys perfect academic freedom to agree or disagree with anyone else. The West had no need for academic freedom because the true authorities on matters of religious doctrine were the bishops in unity with the pope. Islam, lacking such authorities, was forced to adopt a rational way of arriving at authoritative religious rulings in their absence. And the solution was the academic freedom of the professor or muftī. When all the professors, in perfect freedom and autonomy, agreed on a particular ruling, that meant that the ruling was authoritative.

Orthodoxy in Christianity was determined by the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Orthodoxy in Islam was determined by the autonomous consensus of the professors, just as in modern science. In science a particular theory can only become “orthodox” when all eligible scientists study it and arrive at a consensus about its reasonableness and likelihood of correctness. Islam was forced to create this “scientific method” of arriving at consensus due to suffering the same situation that science suffers: there is no higher authority than the scholars, researchers and professors themselves to help them come to legitimate conclusions on the issues under question.

The West took many centuries to digest the imported Islamic concepts of professor and academic freedom. Western professors in the 13th century still lacked the academic freedom that Islamic professors had enjoyed since at least the 8th century. In Christianity, dissent among the professors was considered an evil that led to heresy. In Islam, dissent was the most important way of ensuring orthodoxy, which is why it developed a vast literature of dissent where the disagreements of the professors were recorded.

The idea of a professor freely expressing dissenting opinions had no place in Western civilization until the power of the Church weakened and the professors were able to acquire some autonomy from it.

John Makdisi’s article focuses on the possible Islamic influences on the English common law. His article is an earlier version of his famous 1999 article “The Islamic Origins of the Common Law” (which can be downloaded here). He argues that the assize of novel disseisin, a crucial aspect of the development of the common law established by Henry II in the wake of the Assize of Clarendon of 1166, may have had an Islamic origin, and studies the historical context in which this Islamic influence may have been acquired.

The last four articles by William Ballantyne, Ian Edge, Ann Mayer and David Pearl respectively deal with the issue of the application and integration of the Sharia in modern Islamic states. I discuss the contents of some of these articles in my essay Solving the Problem of the Codification of the Sharia.

April 20, 2019

A Quranic Phenomenology of Atheism

It is common in religious thought to dismiss atheists as obstinate wrongdoers who reject religion out of a combination of irrationality, egotism and their preference for their base desires. But if we appreciate the great honor and dignity that God bestowed on all of humanity (the angels bowed down to us)1, we should perhaps be more willing to explore the atheist’s subjective experience. Another reason to respect the subjective experience of atheists is the great dedication to morality and uprightness that some of them display.

The first book by an atheist that I read was Terry Pratchett’s Small Gods (published 1992). As if by some Discworld magic, the book was being sold by a street bookseller in my Kurdish city of Sulaymaniyyah, Iraq at a time when it was very difficult for me to find English books to buy and read since they were so rare. Since then I have gone on to read 40 novels by him, so of them over 20 times.

Pratchett’s Small God is an all-out attack against Christianity that shows some aspects of Pratchett at their best; his humor and his willingness to admit the good even in the religious. But he also displays a great deal of ignorance about religion like in all his other novels. Since his view of the universe is entirely materialistic, he is unwilling to explore the foundation of religious experience: the possibility of the existence of a soul that instinctively recognizes it creator. By discarding this essential aspect of religion, religion becomes just a silly experiment involving good and bad humans. Good humans like the Prophet Brutha in Small Gods can wield religion to create goodness in the world, while bad humans like Vorbis in the same novel use it to gain power and control.

Terry Pratchett’s view of history is perhaps best summed up in footnote 19 of his Last Continent:

In fact it's the view of the more thoughtful historians, particularly those who have spent time in the same bar as the theoretical physicists, that the entirety of human history can be considered as a sort of blooper reel. All those wars, all those famines caused by malign stupidity, all that determined, mindless repetition of the same old errors, are in the great cosmic scheme of things only equivalent to Mr Spock's ears falling off.

It is one of the greatest failings of Pratchett’s philosophy that he never explores what it is that makes humans morally special. As his career progressed as a writer, he became more and more of a moralist, frequently repeating his teaching that “evil starts when people are treated like things,” which is just a rephrasing of Kant’s categorical imperative to treat humans as ends in themselves rather than as means (things to be used).

But why is it evil to treat humans like things? Shouldn’t a wise person make it one of the goals of their lives to discover this? Pratchett seems to just take it for granted.

In this essay I wish to do for atheists what they are rarely willing to do for the religious: to study their subjective experience in full seriousness. But as a religious person who has studied the questions of morality, I cannot study them on the materialist terms they dictate, since that will get us nowhere. The question of the rightness or wrongness of atheism can only be answered by studying it from a perspective that enjoys a vantage that is outside the box of the universe.

The Covenant of Alast

The Quran tells us:

And when Your Lord summoned the descendants of Adam, and made them testify about themselves. “Am I not your Lord?” They said, “Yes, we testify.” Thus you cannot say on the Day of Resurrection, “We were unaware of this.”

The Quran, verse 7:172.

According to the Quran, all of humanity have already testified to God’s Lordship, and by extension, His existence. By taking this Covenant as our starting point, the justification for God’s perspective on atheism becomes clear; His extreme dislike for it and His view that it is an unjustified choice within our universe.

Humans are not blank slates that go on to either choose theism or atheism based on their upbringing and personal reflection. Humans start out as theists then the knowledge is embedded within their souls while being absent from their brain’s memory.

Imagine our universe as a sphere. The soul is not a part of it, it is outside the universe and looks into it. As Kant and Pratchett tell us, the soul is not an object within our universe and the greatest wrongs of morality start when we treat souls as objects. Souls are subjects, they are like eyes that look into the universe from the outside.

The brain is an object with its own memory and knowledge. The soul is a subject with its own memory and knowledge. The human experience involves a unity of these two different realities.

The soul has knowledge of the Covenant while the brain does not. The point of religion is to bring that knowledge into the brain’s awareness, uniting both body and soul in the Covenant.

Kufr

The Arabic term kufr is used to refer to what atheists do when they reject God. Kufr has a dual meaning that makes it impossible to translate into a simple word in English. It means “to cover”, thus a farmer performs a physical act of kufr when he covers a seed with soil. It also means “to show ingratitude”, thus the Prophet Muhammad PBUH was accused of kufr toward his pagan society when he rejected what they considered holy; they had given him honor and social status, but he displayed kufr in return for these favors.

Speaking from the perspective of the Covenant of Alast, kufr toward God involves two actions: covering and repressing the knowledge of the soul about the Covenant, and displaying ingratitude toward God for His favors upon us, the most important favor being the fact of existing. For every human that exists, an infinite number of humans can be imagined that do not exist.

The very fact of being a self-aware subject looking into this universe is an incredible blessing and favor that requires gratitude.

The Quranic phenomenology of kufr

According to the Quran, one of the essential distinctive features of atheism is hesitation and uncertainty.

Those who disbelieve will continue to be hesitant about it, until the Hour comes upon them suddenly, or there comes to them the torment of a desolate Day.

The Quran, verse 22:55.

Whoever associates anything with God—it is as though he has fallen from the sky, and is snatched by the birds, or is swept away by the wind to a distant abyss.

The Quran, verse 22:31.

Since kufr involves the brain rejecting what the soul knows, it is literally impossible to achieve complete contentment with atheism. The heart cannot settle on it; there is constant tension between the soul and the brain.

The way out of this tension is to build up a rational framework in the brain that can overpower the soul’s knowledge.

Those who took their religion lightly, and in jest, and whom the worldly life deceived. Today We will ignore them, as they ignored the meeting on this Day of theirs, and they used to deny Our revelations.

The Quran, verse 7:51.

The Quran calls this rational framework “being deceived by the worldly life”. In involves taking religion lightly and in jest, and seeking arguments to fortify one’s defenses against their soul’s knowledge. Terry Pratchett and Richard Dawkins are great examples of people who do their best to use both strategies. They cannot help but constantly seek new ways of mocking religion, while also constantly seeking consolation in extra-religious constructs, the most important today being evolutionary science.

This explains a common atheist phenomenon: disgust when religion is mentioned, and celebration when yet another argument is found in support of their reasons for rejecting religion:

When God alone is mentioned, the hearts of those who do not believe in the Hereafter shrink with resentment. But when those other than Him are mentioned, they become filled with joy.

The Quran, verse 39:45.

Religion is an annoyance that always threatens to bring back to sense of tension between the brain and the soul. It is a nuisance that is best dealt with by disgust: the atheist must never study religion too deeply in case this increases their existential discomfort. So they should rather only study religion through the works of atheist preachers like Dawkins who can present religion to them safely; in a way that causes no discomfort but only reinforces the person’s ability to overpower the soul. Dedicated atheists therefore always seek “safe spaces”; atheist echo chambers that can filter out all that is discomfort-inducing about religious thought and philosophy. All that is actually meaningful about religion must be ignored in favor of consoling mockeries about it and consoling scientific theories about how God’s existence is unlikely.

The most difficult thing in life for an atheist is taking religion seriously; to study it as if it is true and finding out where that takes them. This is a heart-wrenching experience because it intensifies the pain of the tension between the brain and soul. It is much better to build an idea of religion made up only of negative facts about it. An atheist has to build a special neural network in their brains that can reassure them that religion is stupid dangerous.

This “atheist theory of religion” is constantly maintained and fortified through the consoling works of atheist preachers. An image of religion is formed that is entirely made up of slivers of historical knowledge that present religion in a negative light: the Inquisition, jihad, terrorism, the abuse of women, the suffering of freethinkers in past ages or modern Islamic societies, the burning of witches, the Crusades, the European wars of religion. This carefully sculpted religious edifice serves as a reference point whenever the atheist is in doubt. Whenever the possibility of God’s existence comes to mind, a cinematic reel starts in the brain that shows images of inquisition, crusade and jihad.

The sin of jaḥd

In fact, it is clear signs in the hearts of those given knowledge. No one disacknowledges Our signs except the wrongdoers.

The Quran, verse 29:49.

The Quran calls the process of finding arguments against God jaḥd (“denial”, “disacknowledgment”). This is not a morally neutral action; it is wrong and brings guilt on the person who does it. Denial of God always involves lying:

Who does greater wrong than he who fabricates lies about God? These will be presented before their Lord, and the witnesses will say, “These are they who lied about their Lord.” Indeed, the curse of God is upon the wrongdoers.

Those who hinder others from the path of God, and seek to make it crooked; and regarding the Hereafter, they are in denial.

The Quran, verses 11:18-19.

Atheism therefore involves dishonesty. The soul knows something but uses the brain to express its opposite. Atheism also involves scheming:

In fact, the scheming of those who disbelieve is made to appear good to them, and they are averted from the path. Whomever God misguides has no guide.

From the Quran, verse 13:33.

The wrath of God

When those who disbelieve see you, they treat you only with ridicule: “Is this the one who mentions your gods?” And they reject the mention of the Merciful.

The human being was created of haste. I will show you My signs, so do not seek to rush Me.

And they say, “When will this promise come true, if you are truthful?”

If those who disbelieve only knew, when they cannot keep the fire off their faces and off their backs, and they will not be helped.

The Quran, verses 21:36-39.

It can be difficult even for a religious person to justify why God expresses so much anger against atheism. If a human honestly seeks the truth and concludes that God is unlikely to exist, why should this be treated with extreme anger rather than neutrality by God?

The reason is atheism can never be an honest choice. It involves the action of a soul that feels God’s presence at all times but that chooses to build a rational framework to justify why it should not submit to God.

The soul of the atheist is like Satan who was in the presence of God, knew God’s power and lordship, yet chose knowingly and intentionally to disobey Him and condemn himself to eternal damnation.

God therefore appear to challenge the human soul: You know I exist, but you have the power to justify to yourself disbelief in Me for a while. So what will you do?

God does not merely let humans rely on their soul’s knowledge of Him. He goes the extra step of convincing the human brain of His existence:

We will show them Our signs on the horizons, and in their very souls, until it becomes clear to them that it is the truth. Is it not sufficient that your Lord is witness over everything?

The Quran, verse 41:53.

When knowledge of God’s lordship are united in a human’s brain and soul, then the human finds himself or herself fully in the position of Satan; standing before God while having the power to obey or disobey Him. They also know that by disobeying Him they are asking for a ticket to Hell. So what will they do?

Life is not a simple matter of a brain seeking to know itself and its relationship with the universe–a blank slate that is slowly formed into a theist or atheist. It is something much more serious. It is a matter of standing before an infinitely powerful God, in full awareness, while having the choice to disobey Him.

For a soul, therefore, disobeying Him is not an innocent mistake, it is treason. God has empowered each soul with His own power of free will. He has raised us to a position of equality with Him in the matter of choice. And this elevation of our status brings us face-to-face with a terrifying reality. Our choices are not simple and innocent choices; they are the choices of a minister who stands before the King. Denying His power and greatness means knowingly choosing to clash with this terrifying power. God, being infinitely great and worthy of worship and submission, accepts nothing short of infinite suffering as punishment for the soul that dares to knowingly stand up to Him.

We may wish for a simpler and nicer universe. But whether we like it or not, we find ourselves stuck in a terrible game where the stakes are infinitely high.

God is utterly kind and merciful toward those humans who do not abuse their freedom in this game and who do not turn their backs on the knowledge that they have deep within their souls.

And as for those who knowingly disobey God, God treats this as a challenge to His greatness and power. When you challenge the Infinite to do what He can to you, what do you expect in return? What higher power, what morality, is there to justify you?

As for those who dispute about God after His call has been answered [by others], their argument is null and void with their Lord; and upon them falls wrath; and a grievous torment awaits them.

The Quran, verse 42:16.

Conclusion

According to the Quran, there is no such thing as innocently choosing to be an atheist. Atheism involves a soul that stands in God’s presence but that chooses to build a rational framework for denying Him in order to gain comfort and consolation for a short while during its lifetime in this world. The atheist, like Satan, knowingly challenges God to do His worst.

Atheism involves a lifetime of asking God to give oneself a ticket to Hell. This wish comes true sooner or later.

I do not wish to suggest that any atheist individual is going to Hell. The fate of individuals is in God’s hands and it should be left to Him to judge each case. But it certainly seems to be the case that to be an atheist is to challenge God to do His worst, at least once the point is reached when both soul and brain are united in their knowledge of God.

Should you visit a friend who suffered a loss if you fear it will burden them?

Selam! I wanted to ask something. A family member of my friend died and i dont know if i should immediatly go to her and visit or let her get trough it for a little while? I few friends of mine are going to her right now but i just think i should let her sort things with her family instead of burging in right after she lost someone. But im scared that i'll look like a horible friend. I dont know if its like a norm to do go or not. What should i do?

Alaikumassalam wa rahmatullah,

I think the best thing to do is consult your family and friends about what to do. While it is good that you do not want to impose on her, it may be taken the wrong way by her and by others. So it may be best to go with your friends even if you personally think that leaving her alone for a while might be better. Visiting her with your friends cannot do any great harm, and later you can always tell her that you thought about not going in order to avoid burdening her and she may like you more for that.

On wanting to make someone convert to Islam

Slam alicome my brother I really like your page and because of Allah and then you, I feel I become good and strong believer in Allah. My question actually is not a question : I know a woman who works in subway restaurant and we like talking about religions sometimes and It’s one of my dreams is to be the reason for making someone Muslim. Can you please help me how to make her Muslim how should I start with what should I say? Thank you

Alaikumassalam wa rahmatullah,

It is natural to wish to share the blessing of Islam with people we like. But I don’t think we should make it a goal to convert specific people to Islam. Wanting to “make” anyone Muslim is the wrong attitude to have. The Quran constantly reminds the Prophet PBUH that he cannot guide to Islam whomever he wishes and that it is up to God to guide the ones He wants:

You cannot guide whom you love, but God guides whom He wills, and He knows best those who are guided. (The Quran, verse 28:56)

Converting to a religion is a very personal experience. Trying to force this experience on someone never works. Rather than attaching your heart to the possibility of her converting to Islam, you should leave the choice completely to her. You can sincerely answer her questions and show her by your good manners that Islam is a good way of life. But you should always remind yourself that even if all of the people in the world tried to convert, if she does not want it, it will not work.

Humans have been honored by God to be able to independently choose their own religion. We do not have the right to interfere with this by attaching our heart to the idea of converting someone to Islam and making them our “project”. Our task is only what the Quran calls balāgh; to clearly and sincerely represent Islam (most importantly by our manners and conduct) and to transmit it to those who want to know about it.

But if they turn away—We did not send you as a guardian over them. Your only duty is only balāgh (communication). Whenever We let man taste mercy from Us, he rejoices in it; but when misfortune befalls them, as a consequence of what their hands have perpetrated, man turns blasphemous. (The Quran, verse 42:48)

Please also see the following articles:

Is dawah obligatory when it is awkward and rude?

What is there to do if you suffer because someone you love is far away from God?

Does it matter to God what religion we embrace?

Does it matter to God what religion we embrace? And is it important to us to know which of all the religion that exists on earth is the true one?

It matters because God has His own plans about how history should unfold. A person born in Islam is part of Islam’s historical timeline, inheriting the history and duties that come with Islam.

We cannot help what timeline we are born into (whether Islam’s, Christianity’s, Judaism’s or some other entity’s timeline). But by being born into it, we become part of a certain historical timeline that we must embrace then work toward self-discovery and truth-seeking. The Quran says, speaking of all the Abrahamic religions:

To every community is a direction towards which it turns. Therefore, race towards goodness. Wherever you may be, God will bring you all together. God is capable of everything.

The Quran, verse 2:148.

So our communal duty as part of our timeline is to race with the other communities in goodness.

But by being human, we all also inherit a personal timeline that includes all of humanity. This is known as the Covenant of Alast (Alast is Arabic for “Am I not?”):

And when Your Lord summoned the descendants of Adam, and made them testify about themselves. “Am I not your Lord?” They said, “Yes, we testify.” Thus you cannot say on the Day of Resurrection, “We were unaware of this.”

The Quran, verse 7:172.

All of humanity has therefore agreed to be part of this Covenant. We have all testified to God’s Lordship over us even before being born. So each human inherits the duties that come with this Covenant: the duty of seeking God and seeking the best way to serve Him.

As for studying other religions to know which one is true, I believe that the human soul has a natural tendency to know when it is acting truthfully and sincerely by the Covenant of Alast, so different humans have different levels of duty toward discovering the Lord. A Muslim whose heart is already settled with Islam has no duty to study all other religions to find out which one is true because their soul has an intrinsic feeling and knowledge of the truth of their path.

But a human who has not adopted a religion that affirms God’s lordship is going to have a soul that feels uncertain and in need of seeking God. Such a person therefore has a duty to study the religions, but most importantly to seek God’s guidance sincerely so that He may guide them to the truth.

It is the duty of all humans to seek God’s guidance, but the duty to study different religions is depends on whether a person’s heart is already settled in the knowledge that they live the truth or whether their heart is unsettled and desiring something better.

April 19, 2019

The foundations of morality in Islam: Reason or revelation?

Salaam. Can I say that religion is one of human needs, and that is to attain inner peace? As for how human beings live on the earth, we are free to make our own rules on how to regulate our people. I know from an Islamic religious group that human should not make their own rules on earth, but rather use God's Law (what they call Sharia Law) and whomever live life according to the rules made up by the geniuses (ones that is more capable in thinking than most of people) is considered ungrateful towards God and is openly disgrace His Greatness? I need your opinion about this. Thank you and I very much appreciate your time.

Alaikumassalam wa rahmatullah,

Attaining inner peace is a side effect of religion, not its purpose. The purpose of religion is to teach us how to form ourselves into that which pleases God the most.

We can discover many aspects of morality (conducting ourselves in the best way possible) by philosophical reflection. God has given us the ability to reflect on history and on the conduct of others and to aim for that which is good and wholesome. The problem is that we do not have any guiding principle that allows us to distinguish between good and evil, right and wrong, in all cases. Morality without guidance will always be on flimsy foundations because our perspective is limited to the human experience. We cannot access the keys of the universe to find out what the best conduct is within our particular universe. If you imagine two universes with two different creators, each of them may have different ideas about right and wrong. The moral rule in one of the universes may be that any society that engages in a particular sin will be wiped out within 100 years. There is no way to discover this based on philosophical reflection alone. People cannot talk to the Creator and ask them what the moral rule is in their particular universe. In the second universe there may be a different moral rule that causes people to be wiped out for a different sin.

So if it is true that our universe has a creator and that he is actively involved in running the universe, in directing history and the fates of individuals and civilizations, then it would be extremely naive to fully rely on our own philosophical reflections to decide moral questions. We may get some things right and some things wrong, and if we get important things wrong, that may cause us to be wiped out before we are able to make a correction.

So the wise thing to do in a universe managed by a creator is to find out the creator’s opinions on morality and to use those opinions as our guiding principles in morality. The creator’s opinions matter more than anyone else’s since they are in charge and can reward and punish us. The right course of action is to submit to the creator for our own safety and well-being rather than ignoring him and completely relying on our own philosophical reflections.

So while we are given enough wisdom to be able to decide many moral questions on our own, it would be arrogant and insulting to cut off the creator from our moral reflections. The creator is the most important moral authority, so their opinions should be our first principles.

This does not mean that we throw away our own reasoning and power of reflection. It means that we should be in constant conversation not just with each other, but also with the creator, through his revelations. In this way we can get a complete picture of morality. Without the creator’s opinions, we can never be sure if our morality is right or complete, and we may make the greatest errors and bring the greatest punishments on ourselves.

I do not support the opinion that all human morality is automatically wrong if it is not based on revelation (the Sharia). Humans can discover many aspects of morality on their own, it is just that their morality will be primitive and deficient without the creator. We do not have super-human intelligence and our universe is not managed by us. So it is only logical and reasonable to rely on the universe’s designer, creator and director on questions of morality.