Emiko Davies's Blog, page 13

May 8, 2017

Interview with Giulia Scarpaleggia on creating her new cookbook

One of my personal favourite food memories of all time was the first time I realised the potential of shopping at my local market in Florence and being able to speak to the other shoppers as well as the stallholders — only I didn’t think to write down all the gems I collected as I took in bits and pieces on what to do with artichokes or how to tell which fennel bulbs are the best.

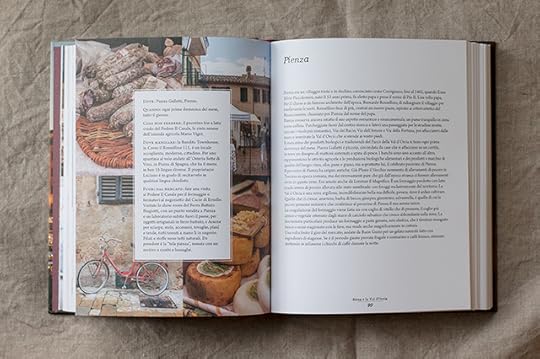

But my dear friend Giulia Scarpaleggia did. Not only, but she spent a year collecting the recipes and images inspired by trips to the Tuscan produce markets and put them all into a beautiful cookbook, La Cucina dei Mercati in Toscana, (“The Cuisine of Markets in Tuscany”) which was released in Italy in February this year by Guido Tommasi Editore.

As Giulia says, “Tuscan cooking is made at home, in grocery shops, in the local vegetable gardens and among the stalls of a market.”

The book, separated into chapters based on different towns or areas of Tuscany (Florence, the Chianti, Siena, Arezzo, Lunigiana, Garfagnana, Pistoia and Prato, the Mugello, Lucca, Pisa, Livorno and the Maremma), talks about the markets, the special produce of each area and the recipes inspired by these things. It highlights exactly what I love about Tuscan cuisine (or indeed any of Italy’s regional cuisines), that each town — not just each region — has its own, unique food traditions.

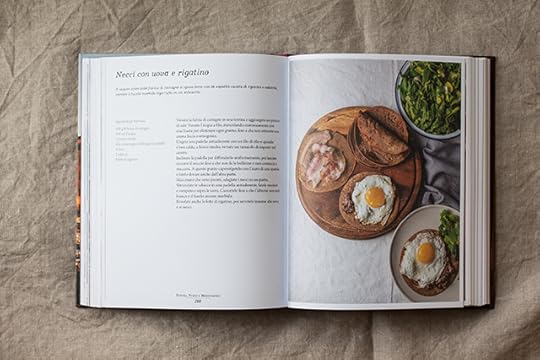

It’s only available in Italian at the moment, but it’s such a treasure that I wanted to introduce English speakers to it by interviewing (a first for my blog!) the Tuscan author on her process of creating this cookbook — from the idea to new discoveries to bumps along the way, along with some photos of a recipe from her book that I made, necci (chestnut crepes) with rigatino (think salty Tuscan bacon) and fried eggs. It immediately caught my eye because I love anything chestnut and anything with an egg on top.

ED: I absolutely love the idea of a cookbook inspired by Tuscan weekly produce markets, how did it come about?

GS: During my cooking classes I often visit local markets with my guests. I see how amazed they are by the seasonal produce, by the fresh fish from the coast and the wide selection of goat, cow and sheep cheese. Going to the local market is inspiring in the kitchen, too. Besides this, after a few times you become friend with vendors and farmers, and you start talking about recipes and ingredients. Queueing at the busiest stands, you eavesdrop pieces of conversations among the nonne who are shopping for lunch and you have the best insights on cooking techniques and family traditions. This is why after a while I felt the urge to write about Tuscan markets, to talk about my favourite ones and have a good excuse to explore Tuscany for more!

ED: Talking to the vendors and farmers themselves at the market is such a great way to get inspired to cook the fresh produce they’re selling. I’d love to know more about how you came about researching and gathering the recipes in the book.

GS: I had a rough idea of which areas and recipes to include. We contacted friends and tourists offices in each area of Tuscany and created a map of interesting markets. Then we jumped in the car and visited all these markets, sometimes more than once, from Lunigiana to Maremma. We tried to mingle among the local clients, buying ingredients and tasting what was on display on the stands. We tried to approach everyone, explaining what we were doing, asking for recipes, tips and ideas. We’ve been very lucky as we found generous people who opened their heart, house, boat and bookshelf to us, sharing traditional and family recipes. I scribbled everything in a little red booklet, and once back home I compared all the recipes with the traditional books on Tuscan cuisine or with my family cooking traditions. [Readers, you may enjoy as much as I did, these portraits of the market vendors she met here on her blog! — ED]

ED: What did you find more inspiring – the produce, the people who you met at the markets or certain culinary traditions in the places you visited?

GS: It is difficult to say, it was very different from market to market. Sometimes the produce was so inspiring that we came back home with a car full of fresh fruit and vegetables, local honey and cheese, fresh fish… and I got to go in the kitchen immediately to cook and test and eat. It was difficult to narrow down to a couple of recipes per market, as sometimes you would have needed at least ten! Other times, people were so inspiring that you would stay there for hours, just listening, as it happened in Viareggio, when we were invited on a fishing boat, in Mugello, when we talked with a famous gastronome, or in Maremma… well, we were together there and our excitement was so clear!!

ED: Speaking with that lovely, elderly woman in Maremma in her kitchen was probably one of the highlights of my year! So I can understand how wonderful the whole experience must have been doing this research and recipe testing for your book. What were some new finds and unusual recipes that you came across while visiting different parts of Tuscany?

GS: Lunigiana was probably the most exciting area, as it is very different from what you might expect in Tuscany. I tried there, for the first time, the barbotla, a thin and crisp flatbread with zucchini flowers, which is usually served with cheese and cold cuts, and the marocca di Casola, a chestnut flour bread. In Arezzo I found for the first time the sambudello, a local sausage made with the leftovers of the butchering of the pork, while in Volterra the most traditional cold cut is the mallegato, similar to buristo but more spiced and with the addition of breadcrumb, pine nuts and raisins.

ED: To me that part, discovering new flavours and dishes, sounds like the best part of researching such a book, though I know from experience it’s not all so easy. I’m curious to know, where there any particularly big hurdles you faced or challenges you had in working on this book?

GS: I guess the most difficult part has been choosing which markets to include and which recipes, as after more than a year of traveling through Tuscany, we had an enormous database of information, recipes, photos and stories that we desperately wanted to include. Pages are limited, though, so we reluctantly had to leave something out. It was also a lot of work, because with Tommaso we did everything, from traveling through markets to photographing the whole book, cooking, testing and writing. Sometimes I felt overwhelmed, like I could not see the end of it, but luckily those were just passing moments.

ED: One of the things that I get asked about is what it takes to make a cookbook, and about the behind the scenes or collaborations involved in getting from an idea to the final book. Can you tell us more about Tommaso, the other half of the Juls’ Kitchen team? I understand he took some of the photographs, as well as being chief taste tester!

GS: And here we come to Tommaso. He’s been a driver, a photographer, a curious spectator, a sherpa (sometimes I lost control at the market and bought basketful of fresh vegetables), a cooking assistant, a dishwasher, a prop stylist, a proofreader, a psychologist and a therapist, and of course the chief taste tester! We worked together since the beginning, since when we began to shape the idea of this book together. Words are mine, I cooked and and I took all the food photos but he took most of the market photos. He is proud to say the the cover photo is one of his photos!

ED: In the world of “instragrammability”, I wondered if you would share what was the best looking market you saw in your travels? And which was your favourite? (Since they could be different!)

GS: My favourite was the market in Livorno, as I have to admit that I love people from Livorno, so open, ironic and fun. If in other markets I had to beg to take some of the photos, in Livorno people were reaching out to be photographer: dé, ma a me non me la fai una foto? And the market is also so colorful, alive, rich and real! As for the best looking market, I left my heart in Florence, at the farmers’ market in Santo Spirito, which is so picturesque and overflowing with flowers and fresh vegetables.

ED: You can find out more about La Cucina dei Mercati di Toscana on Giulia’s blog, Juls’ Kitchen. She runs cooking classes in her home in the countryside near Siena (you can read my account of one of them here, though she has since renovated and rebuilt her beautiful studio) and has another cookbook available in English called I Love Toscana (2012), you can try out her pappa al pomodoro recipe from it here.

April 24, 2017

Borage and ricotta crepes

I had seen it before, those fuzzy, furry leaves and stalks, with the pretty, star-pointed purple flowers, but up until that moment that I saw them sitting in a basket at the market stalls, I admit I had never taken notice of it as a food. It grow along cracks in stone walls and along the roadside near my home in Settignano, which is blooming with spring goodness right now: robinia (black locust) trees, wild garlic (three-cornered leek) and even elderflowers are already bursting.

I asked the vendor just to double check, “Is this borage?” “Si,” Came the answer, “Borragine.” He confirmed. “I’ve had it in ravioli,” I started to say, “Brava!” He said, as if we were about to start a guessing game on what could be done with it. Actually, there’s a lot that can be done with it. If you can use it as a ravioli filling with ricotta, then you can imagine it taking the place of spinach in gnudi, too, but also soups or frittata or stirred through polenta.

I learned that the flowers are just as delicious, if not more interesting, for their delicate cucumber-like flavour — people told me of their use in salads or cocktails like Pimms, and someone even mentioned she freezes them in ice cubes, what a pretty idea for those first warm nights when you can dine al fresco, homemade cocktail in hand. Then there’s risotto and of course the fritters, much like these ones. Or you can simply deep fry the clusters of buds that haven’t yet burst open like these deep-fried robinia flowers.

The problem, I was thinking, as I took home my bag of borage, is that I can’t decide what to make. There’s simply too much choice.

I consulted two of my favourite books that also happen to be cookbooks. Patience Gray’s Honey from a Weed and Luigi Ballerini’s A Feast of Weeds. Both had wonderful ideas for borage (and indeed many other edible, foraged plants). Ballerini’s in particular is an interesting one as it’s a “literary guide” to edible weeds – the chapter on borage starts with a description of the ancient use of borage as a natural mood enhancer and cure for melancholy (the Welsh name for borage, llawenlys, means “herb of happiness”) and includes a quote from Homer’s Odyssey (Helen slips it into the wine “to put an end to the endless whining of her husband, Menelaus”) as well as The Wizard of Oz. It’s impossible not to love, especially when he suggests a recipe for borrage and potato gnocchi.

I finally decided, after reading in Ballerini’s book about a recipe for giant baked pasta shells stuffed with ricotta and borage, to make a stuffing with borage and other wild herbs to fill crepes. Not just any crepes, but tiny, impossibly thin ciaffagnoni, the specialty of the Maremman town of Manciano. The Mancianesi like to say that Catherine de’ Medici’s Parisian entourage of Tuscan chefs included one from Manciano — and that French crepes were born from ciaffagnoni. I had researched and tested these crepes for my cookbook, Acquacotta, but it wasn’t until I called upon some experts at the beautiful Villa Acquaviva, near the town of Manicano, that I truly understood the secret behind making and eating them.

They’re so delicate because they are made from just eggs, flour and water. The same ingredients as pasta, except for the fact that the ratio of water to flour is 2:1. So it’s even more fluid than regular crepe batter, which makes them notoriously difficult to make. I had to throw away my first attempts until I met Valentina Di Virginio, the matriarch and chef at her family’s Villa Acquaviva.

“The first ten will break,” she warned me. It’s more like three, but Valentina is used to making hundreds of these little crepes in miniature pans for their restaurant. She showed me how, as soon as the pan reaches the right temperature (which is hotter than you may think) that they no longer stick or break — as if by magic. You need to hear that chhhhhhhhhhh as soon as you pour in the batter, which will begin to bubble immediately.

She soon revealed more secrets. The batter needs to rest, overnight if possible, for it to become creamy. And her tool of choice for flipping the crepes? A toothpick. Yes. It’s a wonderful tool, actually, I can’t think of anything better — you run the pointed tip of the toothpick around the edges of the crepe to loosen it from the sides of the pan and then, poking the tip through the crepe gently, you lift it and flip it.

Borage and ricotta crepes

Ciaffagnoni di borragine e ricotta

Collect borage that you can be sure is away from polluted areas like roadsides (and hasn’t been used as a dog’s toilet). You may want to wear gloves when you collect and work with borage. It’s characteristic fuzziness is actually thanks to tiny prickles, not as bad as the ones on nettles, but almost. And unfortunately unlike nettles, they don’t lose their prickliness after blanching.

The recipe for these ciaffagnoni comes from my cookbook, Acquacotta, published by Hardie Grant Books. You won’t need all of the batter for this dish (about half will do for this) but with any leftovers, they freeze well, or will still be good the next day or two when wrapped well or kept in an airtight container in the refrigerator. Warm them gently and you can eat them sweet with honey and ricotta or with jam, or simply sprinkled with grated pecorino cheese as a snack.

For the ciaffagnoni:

3 eggs

150 grams plain flour

300 ml water

1 tablespoon olive oil, plus extra for greasing

For the filling:

300 grams of fresh borage leaves and flowers

400 grams of ricotta

handful of wild fennel (or feathery fennel tops, or other favourite herbs), finely chopped

small bunch of chives, finely chopped

1 egg

zest of 1 lemon

salt and pepper to taste

50 grams melted butter

Handful of Parmesan or Pecorino cheese

For the ciaffagnoni, whisk together the eggs and flour until smooth. Add the water and oil and combine. Let the batter rest, overnight, or for several hours, in the fridge.

Heat a small pan (I used a 10cm wide pan) until very hot. Grease lightly with some olive oil. Give the batter a good stir and pour onto the pan, swirling quickly to just cover the surface of the pan thinly (for the 10cm wide pan, this is about 1 tablespoon of batter). The crepe should begin to bubble and cook immediately. When the top begins to look dry and you can run a toothpick around the edges easily, it’s usually a sign that it’s ready. Poke the toothpick gently through the crepe near an edge and flip it over. Cook briefly – 10 seconds – and then remove to a plate and continue with the rest of the crepes.

For the filling, wash the borage well, set the flowers aside and cook the borage leaves in a saucepan of salted, boiling water for three minutes. Plunge into cold water and drain very well, then chop (careful of the prickles) finely and squeeze as much water as you possibly can out of the borage. Place in a bowl with the rest of the ingredients except for the butter and Parmesan. Season well with salt and pepper.

Place a couple of tablespoons of filling along the centre of each crepe, then roll them up like a cigar – they should look a little like cannoli. Place them in a baking dish and continue until the dish is full. You should have about 20 small cigars for 4 people. Pour over the melted butter and sprinkle over the cheese, then bake for 10-12 minutes at 180C. If using larger crepes and more filling, you may need a couple extra minutes. Sprinkle with the borage flowers and serve.

April 17, 2017

Robinia flower cake and fritters + a giveaway!

I have been dreaming about Mimi Thorisson’s black locust (robinia, acacia or false acacia) flower cake since I first came across it a couple of years ago, while searching for recipes using these bunches of white flowers with a strong, heady perfume similar to jasmine or orange blossom.

I’ve been too busy frying them — dipping them in a runny batter, swirling them through a pot of bubbling oil, then eating them crunchy and piping hot, either sprinkled in sea salt or with a scant drizzle of acacia honey (of course), so sweet and clear it’s like syrup. The season of flowering robinia is so short (thankfully it’s followed by elderflowers so that all is not lost) that there was much frying and eating to do in a few short weeks. The result was an article for Food52 on frying flowers and a recipe for fried robinia flowers, or acacia as Italians call them, ended up in my cookbook, Acquacotta, too (giveaway details below!*). They’re the sort of thing you find lining country roads all over the Maremma and for a couple of weeks (usually in late spring), their white blooms can be seen everywhere, hanging from trees like little chandeliers.

I spotted the first robinia flowers — a tiny bit early, perhaps, but we have had a very warm, sunny spring so far — while walking home yesterday to my home in Settignano, in the hills above Florence. A short detour later and we came home with a bundle of white flowers, bees following us. I promptly trimmed the bunches of their leaves and placed them in a large bowl to put in the fridge, covered — it helps prompt any ants or bugs to move out, while also keeping the flowers fresh and perfume intact — until I was ready to make the cake.

Mimi’s cake is a simple cake — eggs, sugar, melted butter, a spoonful of honey and a mixture of cornstarch and flour. She perfumes it with orange blossom water. The petals are picked off (this is the only part that requires a tiny bit of time and care, but it’s a pleasant job, as each time you pick off the petals you get a waft of the honeysuckle-like perfume and also, four year olds can be employed to do this quite well) and folded through the cake before baking. I made a couple tiny adjustments.

Robinia flowers, when cooked, have an ever so slightly peppery, spicy flavour. It makes for an unusual, lovely, afternoon tea snack, made special (because let’s admit it, eating flowers always feels special) with a sprinkling of flowers over the top, and a little milk ice cream or some whipped cream on the side.

I picked so many I had enough for frying too, like the recipe in Acquacotta. Both recipes follow, and in both cases I think you could happily substitute elderflowers, if you can’t find a robinia tree flowering near you.

*By the way, you can win a copy of Acquacotta over at Girl in Florence right now! Georgette has interviewed me about my new cookbook and you can enter and find some more details over on her blog — there are a few days left to enter, just leave her a comment on her blog about what you love to eat while you’re at the sea or the mountains. It’s open worldwide, we’ll pick an answer together and send the lucky winner a copy of Acquacotta!

Some essential tips to collecting flowers for eating:

If you’re organised, bring a pair of pruning shears or good scissors, gloves (the branches have spikes) and a basket for placing the flowers. If, like me, you have suddenly spotted them and are completely unprepared, try to gently break them off a little above the flowers so you have a “handle” to hold them hanging down in their bunches.

Make sure to choose flowers that aren’t in heavily polluted areas, as you want to limit having to wash them — the washing removes some of the pollen, which is part of the perfume, and in the case of frying you really want dry flowers, as the water can make the fried batter soggy.

It’s best to collect flowers in the early morning when freshest — and early season flowers are the most fragrant. Don’t bother with flowers when it has just rained, their pollen and perfume will have washed away.

Avoid old looking or wilted flowers. If they don’t smell like anything they won’t taste like much either.

Eat only the flowers — not the stems or leaves.

Mimi Thorisson’s robinia flower cake (with a few changes)

Find the original recipe here.

12 robinia flowers clusters, pluck the petals only

75 grams of blanched and peeled almonds or pistachios or a mixture of both

3 eggs

120 g plain sugar

75 grams plain flour

30 g cornstarch

pinch of salt

1 tsp baking powder

2 tablespoons acacia (robinia/black locust) honey

90 g unsalted butter, melted

zest of 1 unwaxed orange or lemon

Place the almonds and pistachios in a small food processor and blend until fine – they should resemble breadcrumbs. Whip the eggs and sugar together until light and fluffy. In a separate bowl, measure out the flour, cornstarch, salt and baking powder together. Add the nuts, then fold all of it into the eggs. Add the butter, honey and zest. Fold in the flower petals until everything is just combined. Pour the batter into a greased and lined cake tin. Bake in the preheated oven for 35 minutes. Let cool and decorate with extra flowers all over.

Fiori di acacia fritti (deep fried black locust/robinia flowers)

Recipe from my cookbook, Acquacotta: Recipes and Stories from Tuscany’s Secret Silver Coast (Hardie Grant)

You can serve fried blossoms as an afternoon snack or as part of an antipasto. The result is similar to fried zucchini blossoms, which are really just a vehicle for eating deliciously crisp, fried batter, but with black locust/robinia blossoms, you have a delicate flavour of nectar and spice mingling with that perfume reminiscent of orange blossom. They can be sprinkled with sea salt, dusted in icing sugar or – my favourite – drizzled with locust honey (miele di acacia in Italian). You can use this same batter for frying sage leaves, borage, zucchini flowers and elderflower – together they make an impressive platter of fried flowers and herbs to serve as antipasto. If you’re using the amount of batter in this recipe, it’s plenty to fry about four of each type of flower.

150 grams plain flour

12 bunches of black locust/robinia flowers

vegetable oil for frying

sea salt or 1 tablespoon of honey, for serving

Whisk the flour and 250 ml of water together in a large bowl until smooth. Let it rest and chill in the refrigerator for at least 30 minutes. The batter should be smooth and fairly runny – it should run off a spoon quickly. You may find after the resting time that you need to add a little more water.

In the meantime, prepare the flower bunches by trimming off any leaves and cutting into separate bunches. Leave the stem a good 4–5 cm long – it’s handy for dipping and pulling the bunch out of the oil. Do not wash them.

Pour the oil into a medium saucepan until it’s about 4–5 cm deep – enough oil for the flowers to float in. Place the pan over medium– high heat and bring the oil to a temperature of about 160°C. You can use a sugar thermometer or test with the end of a wooden spoon – the spoon should be surrounded immediately by lots of tiny bubbles as soon as it hits the oil. If the oil starts smoking, it’s too hot – turn down the heat or remove from the heat to cool it down for a moment.

Fry in batches of 3–4 so that you don’t overcrowd the pan. Dip a bunch of flowers into the batter and turn to coat evenly. Holding the bunch by the stem, let the excess batter run off the flowers for a moment. Still holding the stem (tongs can do this if you’re not game with fingers), place in the hot oil, shaking a little for the first few seconds so that the flowers separate from each other. Cook, turning as needed, for about 30–60 seconds or until the batter is crisp and evenly pale golden.

Drain on paper towel and continue dipping and frying with the rest of the bunches. Serve the warm fried flowers with either a sprinkling of sea salt flakes or a drizzle of honey.

April 10, 2017

Spaghetti with monk’s beard

The sudden burst of spring produce in the market after a long, monotonous winter of cavolo nero and bright oranges is one of the things that constantly reminds me why I love living and eating in Italy. A wander through the market like any other becomes, in spring time, a new experience. I feel like a fresh arrival, like it’s my first time walking through my local market.

There are long, twisty fava bean pods, waiting to be podded and munched on with bitey pecorino cheese to tame the bitterness of the raw beans. Thin, long-stemmed asparagus. A lovely array of greens, including radishes with leaves so happy that they become the main ingredient, fluffy-fronded fresh herbs and fresh garlic. Artichokes of many different kinds, but especially the pointed purple ones that are either local, from Tuscany’s Maremma, or sometimes from Puglia or Sicily. Rarely the rounded globe artichokes you find spilling out of crates in Rome, or the tiny, delicate Venetian ones, the so-called castraure (though they often aren’t the real deal, how you can tell is by the price) that you can find in the shadow of the Rialto.

And then there are thick bunches of agretti (salsola soda), looking more like mermaid’s hair than a monk’s beard, their English namesake. A few years ago, this wasn’t such a common sight at the market in Florence. It still isn’t, in that you won’t get them by the crateful like you do fava beans and artichokes, though they’re not particularly difficult to find now. They’re just one of those special things that don’t last long. Blink and you’ll miss them, or come late to the market and they could easily be sold out. It’s worth getting up and out of the house a little earlier for these (a note to myself, of course).

If you’ve never tasted agretti before, it’s worth seeking out if you’re in the right place at the right time and find a bunch or see it on a menu. Frances Mayes likens it to spinach, but notes that it is so much more, “While agretti has the mineral sharpness of spinach, it tastes livelier, full of the energy of spring.” The long, thin fronds have a texture that you would expect from a succulent, with a bite, almost a pop, to them. And it has a naturally salty flavour that hints at the sea — it grows in saltwater, after all.

This unique texture and briny flavour is what makes agretti special and so versatile. You don’t want to mess around too much with it and ruin that uniqueness. You can do things with it that you wouldn’t do with, say, spinach or samphire, another sea-salty green, like this quick pasta dish. It’s essentially an aglio, olio, peperoncino with monk’s beard thrown in, which I like somehow even more for the simple fact that the agretti strands mimick the spaghetti strands and they become one.

But do get an extra big bunch, and try some of it like this, and the rest of it like a side dish, perhaps with some anchovy butter like Rachel Roddy mentions. Or take that and turn it into a dish of its own. Valeria Necchio cooks it with melted butter and anchovies and tops it with an egg, which sounds like my idea of heaven, or at least what I would make if I were stuck on an island since I would obviously take a lifetime supply of butter, anchovies and eggs with me to survive. Hopefully it’s an island like Sicily where agretti grow.

Spaghetti con agretti

Spaghetti with monk’s beard

Serves 4

1 bunch (about 250 grams or roughly half a pound) of monk’s beard (salsola soda)

3-4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves

1 dried chilli

320 grams spaghetti

Put a large saucepan of water on to boil for the pasta. Add about a teaspoon of salt for each litre of water.

Clean the monk’s beard by pulling off any tired looking strands and chopping off the pink roots. Wash in a large bowl of clean water and drain.

Heat the olive oil in a frying pan over low-medium heat and add the garlic cloves. Let the garlic cook gently in the oil, infusing the olive oil without burning or colouring. If you find it’s browning too quickly, turn the heat down, remove the garlic and continue without. Add the chilli and then the monk’s beard, along with a pinch of salt. It will no doubt sizzle and spit when the wet monk’s beard hits the hot, oily pan. Quickly add about half a cup of water (white wine is nice too) and cook, turning with tongs for even cooking, for about 5 minutes or until the thickest part of the monk’s beard stem is cooked through and the fronds are still bright green. If the water for the pasta is now boiling, add the pasta and cook until al dente.

Remove the cooked monk’s beard, along with its juices, to a bowl and set aside while you drain the pasta.

Keep about half a cup of the pasta cooking water, then place the pasta and the greens back into the frying pan and, over low heat, toss together, adding, if needed, another couple of tablespoons of olive oil and the reserved pasta water.

Serve, as is, immediately. A squeeze of fresh lemon juice over this is quite nice and a sprinkling of Parmesan is not out of place but I like it just as it is.

April 2, 2017

The Notting Hill list and a baked fish recipe

I’ve been on the road for over a month, traveling all over Australia for the tour of my latest cookbook, and last week I got to spend the last leg of my book tour in London, in style. We stayed in a bright, spacious apartment through One Fine Stay, who kindly offered to put us up for two of the six nights stay near Ladbroke Grove, a stone’s throw from Notting Hill’s Portobello Road. We absolutely loved it.

Traveling with my four year old, it’s always easier to stay in an apartment, so that it feels a little like home. So we can relax, and be comfortable. So we can cook in the kitchen rather than have to go out all the time, which anyone with kids (especially fussy ones) will know is always a plus — but when we did, we loved this guide to Notting Hill, a timely article by The Curious Pear. The upside to staying in a residential area too is that it’s never that far to a supermarket or a park, which keeps the little one happy. And when she’s right at home, everything is that much easier.

Between Acquacotta cooking classes and demos, foodie talks and podcast interviews, it was such a relief to come back to our home away from home and have a play or stretch out with a cup of tea or a the paper along that big wooden dining table — if only I had a big enough kitchen for one just like it at home.

One night I was even able to host a dinner party along that long table, where I prepared a few dishes from my new cookbook — some warm bruschetta with tomato and anchovies, a comforting acquacotta soup (tomato and onion soup with an egg poached directly in it), sea bream baked in paper parcels with some wild mushrooms and herbs and a sturdy fruit cake called a pagnotella, made with dried figs cooked in wine and dark chocolate. You can find the acquacotta and sea bream recipe amongst these favourites from the book — and the sea bream recipe follows right below too.

[image error]

One of the very handy things that came with the apartment was the use of an iPhone with data so that when out and about you could always find your way home or call an uber or check instagram — genius! The One Fine Stay app installed on the phone also has an excellent map full of recommendations (with personal comments made by One Fine Stay home owners in the area) for places to eat, things for children to do and essential things like the nearest pharmacy. We used it every moment we were out and it was a great way to explore what was nearby.

Some things we loved about our corner of Notting Hill:

Good coffee and a simple breakfast at the quaint cafe Lowry and Baker of organic bacon and eggs — with extra bacon to the tune of mmmmm by a certain four year old (see below)

A wander down Portobello Road for people, dog, building and everything-watching (also picked up some flowers for the house because, well, I could!)

Books for Cooks — basically my dream book shop!

Electric Cinema – old school entertainment complete with comfy sofas

Ukai for a delicious Japanese dinner in a British pub, squeaky wooden floors and all (because we can’t get quality sushi and yakitori like this in Florence)

Four Winters gelato — my daughter couldn’t get enough of watching her very creamy, fresh gelato being made to order right in front of us with liquid nitrogen! Also, it’s conveniently next door to Ukai.

Bea & Co babysitters — in case you need a night off! This was actually our first babysitting experience so needless to say, I was a bit nervous, but they were absolutely wonderful.

Orata al cartoccio con i funghi

Paper-baked sea bream with mushrooms

I am partial to any food preparation that is low maintenance, with a high proportion of delicious eating compared to the amount of effort put into it – and fish baked al cartoccio, or in paper, is one of those things. You bring it home, turn on the oven, stuff it with herbs, splash it with some wine or lemon juice, wrap it in paper, and 20 minutes later dinner is ready. It’s so easy and flavourful, and the fish stays moist, as it is wrapped up and cooked in all its steaming, aromatic juices.

Gilthead sea bream, a local speciality that is farmed in Orbetello’s lagoon, is ideal for this sort of treatment but you could cook any whole large fish this way – sea bass and snapper are also good. I love the combination of mare e monti, and here’s another recipe where the sea and the mountains come together so beautifully. A mixture of earthy mushrooms, tossed with some garlic, make a nice bed for the fish. You could do the same with some thinly sliced potatoes (which, like the mushrooms, will soak up the flavours of the lemon and the herbs beautifully), cooked like the mushrooms before going under the fish – but this bream is also lovely on its own.

This recipe is from my latest cookbook, Acquacotta: Recipes and Stories from Tuscany’s Secret Silver Coast (Hardie Grant Books).

Serves 4

2 medium gilthead sea bream, about 500–600 g (1 lb 2 oz–1 lb 5 oz) each, scaled and cleaned

2 handfuls fresh herbs such as thyme, basil, oregano, calamint, mint, flat-leaf (Italian) parsley and rosemary

2 lemons, 1 sliced, 1 juiced

80 ml tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, sliced

400 g (14 oz) mushrooms, cleaned and sliced

Make sure the fish have been scaled and cleaned; rinse and pat dry. Cut 3 slashes about 1.5 cm (1/2 in) deep along the fleshiest part of the fish, on both sides, season with salt and pepper, rubbing it into the slices and skin. Sprinkle salt in the belly cavities, then stuff with about two-thirds of the herbs and a few slices of lemon to fill. Set aside in the fridge until needed.

Heat half the olive oil in a frying pan and cook the garlic over medium heat for 1 minute. Add the mushrooms along with the rest of the herbs and cook in the oil until golden and softened, about 5–6 minutes. Allow them to cool.

Heat the oven to 200°C (400°F).

Tear a large sheet of baking paper for each fish – about double the length of the fish – and distribute the mushrooms in the middle. Place the fish on top of the mushrooms, then pour over the lemon juice and drizzle with the rest of the olive oil.

Wrap the fish in the paper – bring together the long edges of the paper, folding them down together so they overlap slightly. The short sides can be folded at the fish’s tail and head, towards the middle of the fish and secured with a piece of kitchen string, like a present.

Bake for about 20–25 minutes. Remove the fish from the oven and let it sit, wrapped, for 5 minutes before serving. If using a different-sized fish, you may need to double-check if the fish is cooked properly. To check, unwrap the paper carefully (escaping steam is hot). Take a knife and see if the skin and flesh easily lifts off near the spine. Also look at the gashes – they should reveal opaque, soft meat. If not, wrap it back up and put it back in the oven to check in 5-minute increments.

To serve, you can transfer the whole fish to a long oval plate, dribbling the juices and mushrooms over the top. But I prefer to place it right on the plate, as it is, still sitting in its paper.

March 29, 2017

Meatballs and a love story

There’s a story in my Tuscan family of nobility and forbidden love. It’s set in Taranto, Puglia, on Italy’s southern heel and involves my daughter’s great-great-grandmother. The best known version is told by my husband Marco’s uncle, Riccardo, who remembers it being told to him by his elderly Nonna Anna herself. Anna Michela Comasia Maria Calianno. Her long name was a sign of her family’s noble status. She was born in Taranto, Puglia, in 1889, into a wealthy, well-educated Tarantine family of physicians, surgeons and landowners.

One day, by chance, young Anna answered the door instead of the butler. There was Nicola Cardellicchio, the postman. He came from a poor family of bricklayers and wool spinners, raised by a single mother. “He was no adonis,” noted Nonna Anna. Nicola was rather short and stocky, but she liked him immediately. She continued answering the door whenever the postman passed.

When Anna’s mother, Girolama, noticed her daughter’s growing interest in the postman, she forbid her to see him again, threatening to disown her. So Anna did what any lovesick girl would do: she ran away, eloping with Nicola. The couple had nine children in Taranto — Mario, Marco’s grandfather was born in the middle of the First World War — but times were very hard, and they moved north to Torino to look for work.

Nonna Anna was perhaps not an instinctive cook. I wondered whether she ever had the possibility to learn how to cook. Her grandchildren, Angela (my mother in law) and Riccardo, remember her only ever making lesso (boiled meat) and these polpette, which became variously known in the family as “sugo di nonna Anna” and, oddly, “amatriciana” (which is actually a different recipe, a chilli-spiked sauce of fried guanciale and tomato to coat pasta).

But these polpette – plump meat balls, cooked slowly in tomato sauce, a very traditional dish from Puglia – were passed down to Anna’s daughter in law, Angela’s Tuscan mother, Lina, who made them so often for her own family that she in turn taught her daughter in law, Franca, Riccardo’s wife, who continues to make them today for her own grandchildren and great-grandchildren. It has become this Tuscan family’s recipe, spread throughout the branches of the family tree, made for guests and special occasions especially (it feeds a crowd wonderfully).

Almost everyone makes it exactly the way Nonna Anna did, which has a couple of curious steps: she would slice the onion, fry it in a generous dose of olive oil, then, once softened, she would remove them with a slotted spoon. Then she would fry pancetta in the same oil, and again, once crisp, remove them. Then this onion and pancetta-infused oil was used for making the sauce. I pressed the women in the family to explain why this would be part of the recipe. It seems fiddly, messy and most of all, wasteful — who would throw away pancetta? “Ma non va fatto,” says Franca, noting that you really shouldn’t remove the onion and pancetta. Angela, the traditionalist, protests, “But that’s the recipe!” Perhaps Anna wanted a perfectly smooth sauce without pieces of pancetta floating in it – just their essence. But I’m with Franca, who leaves the pancetta in the sauce.

Traditionally, this is a dish that can be stretched to two courses (or two dinners). The sauce is used to dress bucatini — Mario’s favourite — which can be eaten as the first course, then the rest of the polpette and leftover sauce are served as the main dish, which goes nicely with roast potatoes and a crisp salad.

Polpette di Nonna Anna

Nonna Anna’s meatballs

Serves 6

1 kg mince meat (a mixture of beef and pork is preferable)

2 eggs

100 grams grated parmesan

2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh parsley

1 teaspoon salt, plus more to taste

black pepper, to taste

60 ml extra virgin olive oil

1 large onion, finely sliced

80 grams rigatino or pancetta, finely sliced

700 ml tomato passata

700 ml water

Combine the minced meat, eggs, parmesan, parsley, salt and pepper in a large bowl. Mix very well – hands are always best – until you have a firm, well-amalgamated mixture. Shape into balls a little larger than golf balls. Set aside.

Heat the olive oil over medium heat in a casserole pot. Sear the polpette in batches until they are just browned evenly on the outside, 2 minutes each batch, then remove to a plate – you don’t need to cook them through, you just want them to colour. Turn heat down to low and gently fry the onion slices with a pinch of salt until tender and translucent. Anna would have removed the onion with a slotted spoon and discard it at this point. I leave it in and add the the pancetta, letting it cook until the fat has rendered and become slightly crisp. You can remove them if you like, too, and keep for another purpose or keep them in. I do the latter.

Add the tomato puree, fill the empty bottle with water and add that too. Season with salt and pepper and bring the sauce to a simmer. Return the polpette back to the pot and let the sauce simmer gently for 1 hour, uncovered, stirring occasionally. If you find the sauce is becoming too thick too quickly, you can add a little water at a time. You want a thick, well-seasoned and abundant sauce. You can serve the polpette, coated in a little of the sauce, as a main dish, keeping the rest of the tomato sauce for another day or another course, dressing some spaghetti or bucatini.

March 15, 2017

The Italian Baker: Remembering Carol Field

The Italian Baker is one of the few cookbooks that I own two copies of, so that I have one in Italy and one in Australia and I don’t have to worry about packing it in my suitcase with me when I travel back and forth. It’s one of the few cookbooks that I have sitting on my desk, in the kitchen, ready to be flicked through or cooked from at any moment. It’s a book that I have always found inspiration in, whether it’s for the stories, the recipes, a rustic, dependable loaf for everyday or a special, I’ll probably only make this once kind of recipe project, like pandoro or panettone.

So I was truly saddened to find out that its author, Carol Field, died last week at age 76. Her passion for Italian food culture is contagious. When you read her cookbooks, you cannot help but get just as excited as she does about the waft of someone’s parsley from their garden or the cric-crac of the crust of some wood-fired bread.

In the early eighties when she was writing this collection of baking recipes, a journey that took no less two years just to research, Italian artisan baking was fast becoming endangered, mostly taken over by packaged, highly processed, industrial white bread with no personality, no regionality and no identity. While putting together this list of some of my favourites of her recipes for Food52, I re-read Field’s introduction to The Italian Baker again last night and this really resonated with me,

“Knowing the story and tastes of the regional breads that come out of these ovens is like taking a trip through the Italian countryside. Saving and honouring them is like preserving the stone villages on the hillsides or their churches and frescoes, for saving the taste of the past keeps it alive in the present.”

This book, reprinted in 2011, continues to do exactly that; even though it is over thirty years old, it is still completely relevant. And thankfully, artisan baking in Italy was also salvaged and kept alive too. I have no doubt that this author and this book, with its well-told stories of passionate Italian bakers and their lessons, have something to do with that.

One of the other reasons it’s such a well-used cookbook in my kitchen is that the recipes just work. I find also very interesting her explanations of the difference between baking with American and Italian flours — it all makes so much sense now, why some recipes “work” in one country but don’t in another. How she has “translated” the recipes for use in the home kitchen, dividing the method into various instructions “by hand” or “by mixer” (I am always doing it the first way), is so practical, so user-friendly.

The Italian Baker was with me when I baked my first pandiramerino and my first schiacciata, recipes that I now make with my eyes closed. And it’s always there when I want to try something new. In case you don’t already own a copy of this cookbook, or aren’t heading out to nearest bookshop to get it, here are a few of my favourite recipes inspired by Carol Field:

Schiacciatine Fiorentine

Pantramvai (a raisin bread from Milan, with more raisins than you think you could ever fit into a loaf. I’m obsessed)

Pane all’olio

Roman Maritozzi with whipped cream

Date, Fig and Walnut panettone

Italian cornetti (from my first cookbook, Florentine)

Hand-pulled grissini

February 23, 2017

An inspiring list for the weekend

I’m about to embark on the Australian book tour for Acquacotta, my second cookbook. I’m guessing this is maybe what it feels like to have a second child, you’re just as excited, and a tiny bit more confident because you have been through it before, you promise to yourself to do all the things better, but the universe will likely throw in some surprises just to keep you on your toes!

I’ll be on the road a lot over the next couple of weeks, dragging my four year old daughter with me as I go — she has become a good travelling companion, my constant side kick, even my manager. My first port of call is Orange, New South Wales, where I’ll be doing a workshop with Sophie Hansen whose Friday Lists have always been a favourite of mine (and have obviously inspired this one!). With all the road-tripping I’m doing, I’m using the travel time to do something I have always loved about travelling — time to read and let my mind wander. I thought I’d put together a list of things I’m reading, excited about and inspired by during this trip in Australia, along with a few of my favourite photos so far — as you can see, it’s been all about beaches, the best flat whites, a kangaroo here and there, homemade food and family.

I will miss this beautiful Long Table Lunch with Lean Timms by a week, but I’m very tempted to postpone my flight back to Italy just to go! Lean is one of the photographers (and friends) who I admire the most, keep an eye on her space for other exciting events and her new print shop!

Panettone never lasts long around me, but if you are one of those that has them lying around long after Christmas, Anisa Sabet has this wonderful panettone ice cream recipe to rescue that last panettone.

Valeria Necchio‘s debut cookbook, Veneto, is possibly the book I’m most excited about this year (together with the cookbook of Kate of The Little Library, which was photographed by Lean Timms, and Rachel Roddy‘s second cookbook inspired by her two kitchens in Sicily and Rome). Veneto will be out halfway through the year, I’ve had a sneak peek and I’m pretty sure it’ll be a fixture in my kitchen.

Speaking of cookbooks, another one I want to nab as soon as it comes out is Sarah Glover’s. The evocative photographs taken by Sydney-based photographer Luisa Brimble have been the biggest teasers on instagram (I mean, look at this and this and, oh my, this) — check out their Kickstarter campaign that they have started to fund the self-publishing of this unique, very outdoor Australian cookbook.

I’d love to do a workshop this year and one of the those that I have my eye on is Valentina’s workshops — based between Le Marche and Emilia-Romagna, I find her story, her food and photography always inspiring.

The necklaces made out of carefully broken vintage plates in Emilia-Romagna are all on my wishlist.

Lens and Larder have a dreamy food and travel workshop coming up in late March. Such a dream team.

More workshop talk, but if you’ve ever thought you’d like to run away to Italy and open a B&B, American expats, Ashley Bartner and her chef husband Jason Bartner, know all about it. They are hosting a workshop in April at their beautiful agriturismo in Le Marche.

Andrea Brugi’s wooden boards are not only my favourite chopping boards/platters at home, but now that I’ve seen his home in the Maremma the latest issue of Country Style Magazine, I want to move in.

Loved this thoughtful piece in the NY Times on whether restaurants should offer guests that first taste of wine. Being married to a sommelier this is something we often talk about. What do you think, is it unnecessary if the sommelier does their job or do you like to be part of the process?

The story and the recipe behind Emma Galloway’s nectarine and pickled cucumber rice paper rolls. She gets me every time.

Happy reading and browsing! x

February 12, 2017

Ricotta and baby pear tart from Acquacotta

There’s always something strange about crossing the equator and being propelled into the opposite hemisphere, season and time zone. I tried to explain it to my four year old while we were on the long plane ride from Italy to Australia a couple weeks ago: it’s like the land of opposites – when it’s night here, it’s day there, when it’s winter here, it’s summertime there. She seemed to think that sounded fine, especially the summertime part.

It’s taken about a week to get completely adjusted (after a few torturous wake up calls by a jetlagged child at 3am) and it’s amazing how, from winter, walking right into an Australian heatwave I seemed to have needed to thaw out and rather enjoyed what I’d normally complain about. There’s another heatwave headed to Sydney this week and I’m reverting back to my summertime cooking procedure, a must for surviving the long, hot, humid, non-airconditioned summers that Tuscany also has. The plan is this: no turning on the stove during the daylight hours (this is also the time to keep all those shutters drawn, so as not to let the pesky sun into the apartment). Living off summer fruit, gelato, granita (particularly this one), salads and leftovers cold from the fridge. Cooking, only as a necessity, at night when things cool down.

I generally don’t bake during a heatwave, but sometimes on a bearable night, I leap at the chance to make a tart or a cake that can be enjoyed throughout the week or for a special occasion. This tart is one is one of those.

It’s made with baby pears, known as pere coscia, that can be found in the summertime in the markets in Tuscany. Yellow-skinned, a little firmer than regular pears, but ripe and sweet, they make great child-sized snacks that cause minimal mess, which is one of the many reasons we love them.

It’s a very simple dessert, not overly sweet and pretty enough to present to guests. The whole baby pears are briefly poached in water with a squeeze of lemon juice until just tender but not too soft. The pie dish is layered with the shortcrust pastry dough and smooth ricotta filling and the poached pears are carefully pushed one by one into the filling. Once baked, it’s best when left to settle overnight in the fridge and eaten the next day, chilled, in the summer, and room temperature otherwise.

The recipe comes from my new cookbook, Acquacotta, a book that celebrates a beautiful corner of southern Maremma. These photographs above of our adopted home, Porto Ercole, were taken for it. I’m a little bit old fashioned so I took these with film (not all of the location shots were taken with film, but many were, for the colour and the feel that you can only get with film. I used Kodak Portra 400 35mm film mostly and they were scanned by the lovely people at Carmencita Film Lab in Valencia, Spain). I developed and tested most of the recipes for the cookbook during the summer of 2015 when we lived in Porto Ercole, Tuscany’s longest, hottest summer in living memory. It was so hot, we didn’t leave the house except before 9am or after 6pm and laying low and cool was a priority so the oven never went on. Except for this tart.

I’m about to launch my cookbook and if you’re in Melbourne, Sydney or Canberra I’d love to see you! I will be at Books for Cooks in Melbourne on the evening of February 28 for a talk, some nibbles and wine, at the Canberra wine bar-bookshop Muse on March 5 in conversation with the wonderful Barbara Sweeney from Food & Words, then again at Potts Point Bookshop in Sydney on March 8 for a similar event with Barbara again. I will be adding on a picnic event in Canberra too.

See my events page for more details and the links for booking.

Crostata di ricotta e pere coscia (Ricotta and baby pear tart)

If you can’t find baby pears, you can of course use regular pears, though you’ll have to peel and slice them. Choose firm rather than ripe pears, which hold their shape better. Peel and slice into quarters and remove the core (if they are particularly large pears, you can slice into eighths). Slide them into a saucepan of simmering water with 50 grams (¼ cup) sugar to add a touch of sweetness to them. Cook for 15 minutes or until they are just tender. Remove pears and let drain/cool. Use them as described in the recipe but arrange them in a radiating pattern in the crostata. If you’re looking to use other summer produce, this also works nicely with uncooked, halved and seeded apricots or plums or whole fresh figs.

Recipe edited slightly from my cookbook, Acquacotta, published by Hardie Grant Books and released in Australia, UK and the US in March, 2017.

Makes one tart – serves 8

For the pastry:

250 grams of flour

120 grams of caster sugar

125 grams of cold butter, chopped

pinch of salt

1 egg plus 1 egg yolk

For the filling:

500 grams of ricotta

120 grams of caster sugar

zest of 1 lemon

1 teaspoon of vanilla essence (or scraped seeds of half a vanilla pod)

2 eggs

7 baby pears, peeled and poached until just tender

powdered sugar, optional

Combine the flour sugar and butter together in a bowl and rub together with fingers until there are no more visible pieces of butter (or you can pulse in a food processor). Add salt and egg plus yolk and combine until it comes together into a smooth ball. Place in fridge to rest 30 minutes then roll out on a lightly floured surface to about 3mm thick. Lay over a pie dish (about 22cm diameter) and trim the borders (you can freeze any leftovers or roll them out and cut out shapes like sugar cookies). Prick the surface gently all over with the tines of a fork.

To make the filling, combine all the ricotta, sugar, lemon zest, vanilla and eggs and mix until smooth. Pour over the dough-lined pie dish and smooth over. Carefully push the cooked pears (or other fresh fruit) into the ricotta filling then bake at 180ºC for 45 minutes or until the top is firm and slightly coloured golden brown and the pastry crust golden.

Let cool completely before serving (as mentioned above, I recommend baking this at night and letting it cool overnight, chilled in the fridge before serving) and, if you like, sprinkled with some powdered sugar – this will mostly sink into the surface of the ricotta and the pears so you won’t see much of it but it will add a hint of sticky sweetness. Store this tart in the refrigerator and eat within 3 days.

January 22, 2017

Seasonal cooking classes at Latteria Studio in Rome

I have a disclaimer, right off the bat. I love the Latteria Studio and the people involved in it.

Alice Adams (pictured here above) who runs the show, is a longtime resident of Rome, a food stylist and recipe developer from Melbourne with an Italian husband and two bilingual kids. She worked on my latest cookbook with me and we hired many of the beautiful props from the studio. I feel like she is the big sister I never had and after the week we spent shooting Acquacotta, it felt like we have known each other since forever.

Then there’s Rachel Roddy, who you probably already know. Rachel is a dear friend though before we met I read her blog and hoped one day I’d be lucky enough to meet her and talk about food (or rather listen to her talk about food!). She is always an inspiration to me in so many ways, as a mum, a writer, and generally lovely human being.

The generous and knowledgeable Carla Tomasi was the only one I hadn’t actually met in person when I came to do one of the infamous Market to Table classes at Latteria Studio, but I felt as though we already knew each other, simply through our connection with Rachel and Alice but also because instagram has a funny way of doing that.

So I knew immediately when I came along to one of Carla and Alice’s classes (that’s Carla above left and Alice at the stove top; Rachel is normally there too), that I would feel right at home in the studio, which is one of the loveliest things about it. It’s made like a home kitchen, rather than a professional one, with a large marble table that runs down the middle so there’s plenty of bench space for rolling pasta. At the end, everyone sits down on a beautifully laid table to eat and drink and chat together and by then (or even well before it) it feels like being amongst friends, even though hours earlier we’ve all only just met.

We start the morning in the Testaccio Market, with Alice picking up puntarelle, artichokes, beautiful wild mushrooms and other goodies from her favourite fruttivendoli. She talks us through the seasonal produce and typical Roman specialties, while we nibble on some of the sweetest mandarins. We waltz past da Artenio for a snack of Roman pizza topped with red onion (and the lingua della suocera, “mother in law’s tongue” bread sticks studded with olives, looks good too!). After our market visit, we stroll to the studio, where Carla waits for us with open arms and negronis — a wonderful combination.

The class format is an enjoyable, natural mix of Alice poaching pears in spiced red wine for topping an Elizabeth David-esque walnut and chocolate cake, Carla showing us how to make a silky focaccia dough or mincing wild mushrooms for the filling of her chestnut ravioli, us jumping in here and there to chop, stir, knead, sip, and all the while listening to Carla and Alice’s stories and instructions. There are some classic Roman vegetable dishes, carciofi alla romana (artichokes stewed in garlic, wild mint and wine) and a beautiful salad of puntarelle shoots, which are pushed through a handy puntarelle cutter (can you see it in the photo below right, a little wooden square with a wire grid?) for perfect, thin, crunchy wisps of chichory shoots dressed in anchovies and garlic. It’s one of my favourite things, ever.

Anyone who knows Carla knows that pasta is one of her (many) specialties. Watching her make pasta is absolutely mesmerising — as she rolls the dough through the pasta machine, it’s as if the sheets of pasta are an extension of her hands. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. Sheets of chestnut pasta were rolled to make ravioli, filled with an intense, delicious mushroom paste that had been cooking slowly and carefully on the stove top. She also shows us maltagliati, with parsley leaves pressed between the sheets of dough for pretty, green touches nestled in the frilled-edged pasta.

There’s so much to learn, but above all, to enjoy at the Latteria Studio. It’s friendly, it’s delicious, it’s all done in real time, glass of wine in hand, with as much or as little involvement as you’d like. And whether you’re a long time expat or first time visitor to Rome, it’s a wonderful way to learn about and taste a little of the Roman way of life.

Latteria Studio’s puntarelle salad

With thanks to Alice Adams for sending me the recipe. It’s hard to find puntarelle outside of Italy (or indeed outside of Rome; even in Florence, it’s not a common sight), so this may be difficult to attempt if you don’t have it. BUT if you’re absolutely dying to get a taste of this until you can get your hands on puntarelle, I found it really interesting that Prune chef, Gabrielle Hamilton, suggests substituting belgian endive for puntarelle — indeed it has a similar bitter, juicy, crunchy texture.

1 bunch of puntarelle (chichory shoots)

1 garlic clove

4 anchovy fillets packed in oil, drained

1 teaspoon lemon juice or red wine vinegar

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

To prepare the puntarelle, pull away all the long leaves and snap off or cut off just the short shoots found underneath the longer leaves. Finely slice them (or push them through a puntarelle cutter) and place in a bowl of ice water to crisp up (and they will get their characteristic curl from this too), while you prepare the dressing.

Blend the ingredients in a mortar and pestle, starting with the peeled garlic and anchovy fillets. Gradually add the olive oil and vinegar. Drain and pat dry the puntarelle, then toss with the dressing and serve immediately.

For Latteria Studio class information and event schedule, see here.

Emiko Davies's Blog

- Emiko Davies's profile

- 13 followers