Rachel Neumeier's Blog, page 347

March 14, 2015

Ooh, horse stories!

When I was a kid, I was as into horse stories as any clichéd teenage girl ever. Also, I still love it when a great horse appears in a novel. Bansh in RANGE OF GHOSTS, for example.

Well, here is a post at tor.com from Patricia Briggs on “five books with fantastic horses.”

Okay, I must certainly look up A WIND IN CAIRO. Okay, I just picked it up. MY GOD MY TBR PILE, it is going to cause a gravitic implosion and most of it isn’t even physical. It’s especially ridiculous because I don’t have time to read fiction right now anyway. Maybe in April. Late April.

Anyway, I, like Briggs, enjoy the ponies in Anne Bishop’s WRITTEN IN RED series, though they do add to the rather high Implausibility Quotient of the series.

Horses that Briggs didn’t mention:

Bansh, as I mentioned above. I see a lot of commenters at Brigg’s post love Bansh.

Copperhead from LMB’s Sharing Knife series.

The pooka from THE GRAY HORSE by R A MacAvoy

The sea horses from Stiefvater’s THE SCORPIO RACES.

While on the subject of violent carnivorous “horses,” maybe the horses from CJC’s CLOUD’S RIDER. Do they count?

Oh, I like Dun Lady’s Jess! From the book of the same name, by Duranna Durgin.

Okay, what other great horses from fantasy am I missing? Bonus points if the horse is a Real Horse and not a Horse-Shaped Human Person.

Literary no-fly zones

I saw this post at Book Riot yesterday. It is a really delightful post by Raych Krueger on Stuff I Won’t Read and how that has changed during the author’s life.

I used to be able to read any old thing I wanted, except for books about torture. Torture has always been my Number One Do Not Want. If someone ever writes the novelization of Game of Thrones: The TV Version (I KNOW THEY ARE ALREADY BOOKS, MY DUDES, don’t even look at me like that. But GRRM is more restrained about his torture than Messrs Beniof and Wiess, and doesn’t just hang out there for pages, peeling a person), I will not be able to read the Theon scenes.

But unless someone was being flayed (why is that even a thing? Whose terrible, terrible idea was that in the first place), I was pretty down to read. EVEN IF THERE WAS A DOG DEATH, as long as it wasn’t protracted, I could muscle my way through.

Then I had a kid, and then I had another kid, and everything went tits up. Gone are my salad days, reading with the gleeful heedlessness of youth, where nothing really bad had ever happened to me and nothing on earth could break me.

The whole post is fun to read, you should definitely click through if you have time. But it’s also interesting. Actually, there are two Don’t Read That kinds of things for me: JUST SKIM THIS PART and DNF THIS BOOK, and they are completely different.

I’m with Raych: no skinning people alive. No no no. But that kind of thing is much worse for me if presented visually, on TV or in a movie. (Mental note: yeah, maybe no need to ever get around to watching “The Game of Thrones.”) Because not only does it seem more “real” with the added visual, it’s harder to skip over.

I can handle a dog’s death. I can! I’m tough. But I’m likely to skim over any dog-lost-on-the-street scenes. And if the book contains a significant portion of dog-lost-on-the-streets, then it better have a happy ending.

For me, I skim lightly over: Torture scenes because ugh. Detailed erotica, because I feel like a voyeur reading that, seriously. Almost all bad-guy points of view, because not interested.

For me, DNF categories include: Too much Emotional Emoting from the protagonist, because I am really not into angst. Or, the author is attempting to jerk me around emotionally and I can tell. Or, the author gets too much of the science wrong, and it’s science I particularly care about. (It’s okay with me if Superman picks up a whale without squishing right through to bone and then having its entire skeleton disarticulate around him. I know you cannot pick up a whale without lots of bad stuff happening to the poor thing, but I don’t care that much about physics.)

I once stopped in the middle of a book and wrote down a list of all the reasons you cannot have giant bugs and spiders the size of Cadillacs because until I did that I COULD NOT COPE with the impossibility of giant bugs. But the book wasn’t bad, actually, and I did finish it. (I can’t remember what it was, though, sorry.)

This is all aside from “The book just isn’t that great” or “The book just isn’t catchy.” I DNF quite a lot of books because life is short, right? But here I’m thinking of stuff that makes me stop in the middle and give a book away even though it’s well written and/or catchy.

How about you? Have you got a clear distinction between “the book is great but skip pages 55-81″ and “the book is well-written but too annoying to finish”?

March 13, 2015

When is it diversity and when is it cultural appropriation?

Someone asked Janet Reid a question about cultural appropriation recently. I’m reproducing the question and Janet’s answer in full here:

My current WIP features a young Alaska Native man, and while he’s not the MC, he has a very prominent supporting role (he is actually one of my favorite characters), and there are several other minor characters who are also Alaska Native. Since the book takes place in Alaska, this is appropriate, I believe. I am not an Alaska Native, but I have lived in Alaska for 26 years and I have many very dear friends who are. So while I don’t have personal experience being IN this culture, I hope that my associations with it (and extensive research) will create a voice that rings respectful and true. I also have zero experience being a man, but while that’s a whole different can of worms (no pun intended), for some reason don’t see that as big of an issue.

My question is this: I am hearing a lot of call for diversity in novels, which is awesome, but I am also hearing criticism about writers appropriating a culture for their own means. Obviously, writers must write outside their own reality (otherwise, what’s the point?), but when does writing about a race or culture outside your own become appropriation? We’ve discussed this a bit in our writing group, but I’d really love to hear your perspective on this. Thanks!

This is a tough but interesting question. It’s very much akin to getting things “right” when simply by being a visitor to the culture, you can’t know what’s “right” down to the last detail. You will always see the culture through the prism of outsider.

That does not mean however that you can’t write fully developed and interesting characters from that culture. The key is like that of all good writing: make it feel authentic, but not just to you, to the people from that culture.

Appropriation is a loaded word for writers, whose job it is to steal everything they can and write about it. When does it cross the line? Everyone is going to have a different view on this, but the thing to pay attention to are people in that culture.

I didn’t understand that The Help wasn’t a fun book until I read the comments about it written by Roxanne Gay. While it’s not about appropriating culture, it does seem to say that stories are given a wider audience only when those in power agree to tell them.

I’m not sure there’s a real answer to your question. I think by asking it, by being aware of the problem, you’re on your way to steering clear of it.

This caught my eye because it so clearly gets at a current double bind that faces many writers today: We may want to write diverse characters and place them in non-American, non-European settings, but those of us who are white American (or English, or various other) writers are also likely to be perceived as practicing cultural appropriation if we do.

In fact, if we set a book in a culture clearly derived from a contemporary non-American culture, I believe there is a 100% certainty that some readers will have that perception.

For example, take THE SUMMER PRINCE by Alaya Dawn Johnson:

Beautiful cover, isn’t it? That’s what first caught my eye.

Here’s a snippet from the back cover:

heart-stopping story of love, death, technology, and art set amid the tropics of a futuristic Brazil.

The lush city of Palmares Três shimmers with tech and tradition, with screaming gossip casters and practiced politicians. In the midst of this vibrant metropolis, June Costa creates art that’s sure to make her legendary. But her dreams of fame become something more when she meets Enki, the bold new Summer King. The whole city falls in love with him (including June’s best friend, Gil). But June sees more to Enki than amber eyes and a lethal samba. She sees a fellow artist.

Now, here is a post by Johnson about writing this book, over at Scalzi’s blog Whatever.

Alaya Dawn Johnson: I tend to write my novels the way other people quilt, in a somewhat-ordered patchwork of varied materials that have arrested my interest. Which means that whenever I discuss my inspiration for The Summer Prince I end up babbling about matriarchies and fame and what a non-heteronormative society might look like when projected into the future of African diaspora culture in Brazil, plus music and art and human sacrifice (I thought about including reincarnation, but that seemed like overkill).

This is an SF story that is, I gather, on the boundary between YA and adult. Johnson makes it clear that she sent this manuscript to Brazilian readers for comments as part of her attempt to get details right, even though the culture she creates in this book is very different from contemporary Brazilian culture.

Here’s Liz Bourke’s take on this story:

It’s easy to see why The Summer Prince has received a significant amount of acclaim. This is a tight, compelling book with an awful lot of things to say about art, about politics, about principles and compromises, about the prices people have to pay to make a difference, and about power and inequality. At less than 300 pages long, it’s a very compact story: it’s also incredibly effective.

Palmares Três is a city in what was once Brazil. A city with very little traffic with outsiders since the series of catastrophes that changed the world, but a city built on tradition as much as technology; a city ruled by the Aunties, and by a Queen who is chosen at regular intervals by the Summer King at the moment of his death. . . . It’s a powerful, deeply affecting book. It doesn’t pull its punches. Fluently written and elegantly put together, it’s an absolute joy to read.

You all know I greatly respect Liz Bourke’s opinion, right? I already have this book on my wishlist / TBR pile / a sample on my kindle — I don’t remember, but one way or another I have this book marked so I won’t forget about it.

But here is Book Smuggler Ana’s take:

But [this is] a Brazil that only an outsider could write. Because the story focuses on the parts of history and culture that an outsider would highlight, and none of the insider knowledge that goes much beyond the surface. And I want to be careful here because it’s not like I don’t appreciate and admire authors who want to move the focus from Europe/US to elsewhere in the world. I also have read interviews with the author (and even briefly met her at BEA a couple of years ago) and I believe in her good intentions and that she tried to be as respectful as possible, which just goes to show that even the best intentions can go awry.

Ana is half-Brazilian, half-Portuguese, btw, from Rio de Janeiro, and has studied Brazilian history. So there’s that. The comment thread at The Book Smuggler’s post is interesting, too, as for example a commenter (Sheila Ruth) suggests that perhaps the reason Johnson has her characters address their parents with terms equivalent to “mommy” and “daddy” is not because she thinks those terms are used by real Brazilians today but because she knows they aren’t, but is showing the infantilization of adults in that futuristic culture. It’s quite true that if you are deriving a futuristic culture from a current day culture, it is going to change.

I don’t know. This doesn’t come up when you set a fantasy novel in a purely secondary world. But the more closely you base your setting on a recent historical setting or an actual contemporary culture that isn’t yours, the more likely you are to a) make mistakes; b) use details that seriously turn off readers more familiar with that setting than you are; c) be perceived as guilty of cultural appropriation.

I know that there are mistakes in the Spanish in BLACK DOG, even though I had a friend who speaks contemporary Mexican Spanish check the manuscript. This happened because when I was correcting the Spanish from Online Translator PseudoSpanish to real Mexican Spanish, I missed some lines of Spanish. Since I don’t speak any Spanish at all, I couldn’t tell those mistakes were still in there. Nor could the proofreader, obviously. Well, now I know: have Spanish-speakers check your manuscript twice. Or three times. So that shouldn’t happen again. But this problem was a serious turn-off for some readers, as you can imagine, as well as highly embarrassing for me.

But this whole topic worries me a bit, because I have a partial manuscript right here (rattles bytes illustratively) for a story set in an alternate world that draws very heavily on the Ottoman Empire. And another idea for a secondary-world fantasy that is set in a culture strongly flavored by real SE Asian cultures. My inclination for both is to step a bit farther away from historical markers of either real setting, and then a bit farther away — make the settings more and more secondary, in other words — in order to avoid potentially offending readers more familiar with real historical settings than I am. But if authors avoid historical or non-American/European contemporary settings, fewer books set in those cultures will appear in modern fantasy literature. Is that what we want? That’s not what we say we want.

Speaking as a writer, I perceive this as a real dilemma, with horns and everything.

March 11, 2015

No, really, YA is an artificial category

As is true for basically all marketing categories, the line between “young adult” and “adult” fiction is completely artificial. This is why I am not a huge fan of breaking out new categories such as “new adult.” What’s next, special designations for every age group by the decade? Heaven forbid we should accidentally read a book featuring a pov protagonist who is twenty or thirty or fifty years older than us. How would we cope with this alien point of view?

Somehow it’s always younger readers who are implicitly told they shouldn’t read “up” in age. Older readers can read whatever they like. Who would look twice at an older person reading books that feature protagonists in the prime of life? Especially since the vast majority of books do feature protagonists younger than forty. But now we have twenty-something readers pushed toward, if you please, “new adult,” as though the only concerns they can reasonably be expected to be interested in are those dealing with the formation of new romantic attachments and the establishment of careers.

The reason YA in particular annoys me as a category is because, now that it exists, parents and teachers and librarians and booksellers all shove teenagers in that direction. It’s all very well for adults, new or otherwise. Adults can choose to read whatever they want, including YA. But the constant shove of young readers toward “age appropriate” titles has got to have more influence than other kinds of categorization, especially since many kids are not making their own buying decisions. And because of the basic expectations of the categories, writers are expected to either aim their book at YA, with a teenage protagonist with certain kinds of concerns and a definite coming-of-age arc; or at adults, with a protagonist who is generally, what? Twenty-two to thirty-two or thereabouts.

We talk about diversity in YA, about the important of encouraging an understanding of and empathy for all different kinds of people. This is great, it’s perfectly true that this is very important. But we also implicitly limit this to “Different kinds of people who are all about your age.” I don’t think that is such a great thing.

Writers as well as readers are constrained by category expectations. There used to be, I think, more books aimed at children or teens with adult protagonists than there are now. Or if not more, at least some, and some very popular ones, too. How about Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH? Mrs Frisby is an adult mouse. Her concerns are those of a mother. I don’t recall having any problem “getting” her point of view. That was originally published in 1971. As MG and YA have become more canalized in their expectations, it seems to me that it has become less possible for a kid’s book to feature a middle-aged mother as the protagonist. Today, I strongly suspect that the author of such a book would make one of the children the protagonist, setting the mother into the background. If the writer didn’t make that decision, I could imagine an editor suggesting it in order to make the book more marketable.

I loved the Mrs. Pollifax books when I was a kid. These mysteries seem to me to be very suitable for young readers. They are written at, what? The eight-grade level, maybe? I had no problem relating to this older woman protagonist, a widow with grown-up children. I definitely think this series is perfectly suitable for younger readers as well as adults. But how many parents, teachers, or librarians would think of suggesting them to younger readers?

One of my all-time favorite books when I was a teenager was The Count of Monte Cristo. “Relatable” protagonists are often rather overrated; or at least I hope very few readers really see themselves in Edmond Dantes. But what a grand revenge epic!

I actually thought of all of this today because of something that puts a different spin on the same kind of idea: this review by Sherwood Smith at Goodreads. It is a review of AKH’s The Pyramids of London. Here is a paragraph from that review:

This is not to denigrate traditional publishing. I like traditional publishing! But it has its limitations: supposing one reaches an enthusiastic editor (and I don’t know why traditional publishers are not all over Australian writer Höst–or maybe they have been but she’s determined on the indie course) but anyway, supposing this book jazzed an editor as much as it jazzed me, where would the sales force slot it? There are dual POVs, equally important: three teens whose parents died under very mysterious circumstances, and their 36 year old aunt, who inherits their guardianship and is determined to find out why they died. Her POV is that of an adult, the kids are kids, their motivations believable when they pitchfork themselves into trouble with all the best intentions. Steampunk or alternate history? Fantasy or mystery? It is all of these things!

Exactly.

Also, as an aside, I second the bafflement about why editors haven’t actively tried to recruit Andrea Höst (though, like Sherwood Smith, I don’t know that they haven’t).

But, basically, yes, this book would very likely present a puzzle to the marketing department.

I don’t want to be too dogmatic about this, however. I do think age-based categorization *fundamentally* causes an unfortunate limitation of the reading choices presented to younger readers, and also *fundamentally* creates a set of unfortunate constraints for writers.

But. But, you know, The City in the Lake has both a young protagonist (Timou) and an adult protagonist (Neill). My editor didn’t stop me from writing the book that way. As I recollect — this was some time ago — she did nudge me away from trying to do that again. City was my first, of course. I don’t think I would divide the pov that way again, unless I was more or less planning to self-publish a title.

However, given Andrea Höst’s Pyramids and my City, I am curious. Can anybody think of any other titles that feature both important teenage and important adult protagonists? Recent titles, or older ones?

Can anybody — and I know a couple of you are librarians — think of recent MG or YA titles that feature only an adult protagonist? ARE there any books you recommend to younger readers that feature middle-aged or elderly protagonists? Given the flood of MG and YA titles released every year, I must say, it’s a bit hard to imagine nudging younger readers toward any older title (except for classics such as Little Women, maybe). But does anything leap to mind?

March 9, 2015

Writing advice: keep it personal

So, I just happened across this post at Black Gate, by M Harold Page, about how you shouldn’t polish the beginning of your novel up too shiny, because it’s probably going to totally need to be re-written at the end.

This is nonsense.

By which I mean, of course, it’s nonsense for me. I polish the bejeezus out of the beginning of my novels and they definitely do not need to be significantly re-written at the end. This is because for me, the beginning drives the rest of the novel, including the worldbuilding and the character development. I have never, not once, changed the beginning of one of my books in any substantial way — though one time I moved the opening down, made it chapter two, and written a new opening. Oh, and I’ve gone through and cut prologues as hard as possible twice, because prologues, you know. Generally they should not be too long.

So when Page says:

Just imagine you spent three days honing the perfect opening paragraph leading into the perfect scene, kicking off the perfect first chapter?

Then, three months later you come back and have to make the following changes…

…the tall male NCO called Geoff is now a buxom female NCO called Janice. The barracks are now a ruined farmhouse. The unit’s rail guns are now laser carbines. Their power armour is now light weight skin suits. The red second sun is now a blue dwarf. The tank is now a grav skimmer. The comedy alien in the unit has been deleted. The hero no longer has a girlfriend back home. He does, however, have a recently slain boyfriend…

I am baffled at how this could possibly happen. I mean, I recently sent the first 100 pages of a manuscript to my RH editor. It is a polished 100 pp and that’s all there is. There isn’t another rough 100 pages. There isn’t a detailed outline. Well, okay, there is a very rough and probably highly misleading synopsis that sort of suggests where the story might be going. But that’s it: 100 polished pages and a very (very) rough synopsis. Because that’s how I do things.

But that’s just me. No doubt someone out there read that bit about never bothering to polish the beginning and thought, Yeah! Right on! It’s just like that!

So that made me go poke around a bit until I found this:

World building is an important component of fantasy writing because your fantasy world must be grounded in a history and abide by certain rules in order to persuade your readers to suspend their disbelief when you bring in magic, fantastical beasts and other implausible elements. Below are some of the important questions to ask yourself as you begin your world building.

1.Where is the story located? Is it a past, future or alternate Earth, or is it another planet or another dimension?

2.Who are the main intelligent inhabitants of this fantasy world? Are humans the only intelligent species, or will there be creatures like dwarves, fairies, elves and more? Alternately, will there be species you’ve made up?

3.What is the government system in the part of the world you’re focusing on? Is it a monarchy, a republic, a democracy, a dictatorship or something else?

4.What is the rest of the world like? What types of government and inhabitants are there? What is the relationship of the people you’re writing about to the rest of the world? Are they the dominant culture, or are they dominated?

5.What important historical events have led to the present situation? What wars, alliances and other situations are relevant?

6.Technologically, how does the fantasy world compare to our world? Is it more or less advanced, or does it have a mix of technologies?

7.What is the standard of living for average people? How educated do they tend to be? What does “educated” mean in this world?

8.Does magic exist in the world, and if so, how is it regarded, and who practises it?

9.What are the most important values of the society that you are writing about? What type of religion do people practise?

10.What is the class situation in the society you are focusing on? Does one gender or race tend to be favoured over another?

I knew I could find a list of questions like this, because you do see them around. They baffle me. I can’t even imagine. How can anybody have time to write the actual novel if they pour all their time into thinking about stuff like this? Why not simply build the world by writing the novel? The history and political situation, the maps and cultural details, the art and architecture and attitudes, will sort itself out for you if you just let it.

At least, that’s how it is for me.

All this stuff — about how to build worlds, develop characters, get through the slog that comes in the middle of the book; everything about when to polish to a high gloss and when to stick in a filler with a note to come back and finish that bit later — it’s all personal. All of it.

That link to the slog through the middle? That’s a post by Timothy Hallinan about The Dread Middle. I agree with every word. But that’s just me. Well, and Hallinan, obviously. I can’t imagine anybody disagreeing. But I know people do, because I’ve met actual live writers who think the middle is the easy part.

I KNOW, right?

Also, it’s quite true some posts that offer writing advice are more nuanced, thoughtful, and broadly applicable than others. This link goes to Kate Elliot’s recent (excellent) column at tor.com on writing female characters.

Incidentally, my casual search for things like How to Write Believable Characters and so on also turned up a good many posts dispensing advice on how to write male characters, how to write believable teenage characters, and so on. This is a popular type of advice, and always something to think about, though I can’t quite imagine approaching character development so analytically. I do remember my brother commenting that although he likes Sarah Addison Allen’s stories, he doesn’t always find her male characters believable. But basically I think that Kate Elliot is dead right that first you think about writing believable human characters and then you go from there. Unless, of course, your characters are not human.

As far as that goes, I guess I’ve written both male and female characters, both adult and teenage characters, and in fact both human and decidedly nonhuman characters. To me they are all people first and I generally like and sympathize with them all, even when they’re opposed to one another. I even sort of liked Lilianne, in a way.

Anyway, the point is, an awful lot of links to posts about writing advice drift through my Twitter feed (during an average day that is not consumed by llamas or The Dress). I follow some of those links because it’s sorta interesting to see how other people write. But in general? In general, I do think it is best to phrase your advice like so:

Many writers find that . . .

In attempting to build a believable world, you may discover that . . .

When beginning a novel, I personally . . .

And so forth. Really, most writing advice would benefit from the author remembering that it honestly is all different for someone else.

March 8, 2015

Page critique, illustrating a common failing

I see that Nathan Bransford has a page critique up at his blog today.

Here are the first few paragraphs, with Nathan’s deletions and additions shown:

The taller man stood near the third floor window, scanning the crowd of parade-goers lining the streets. He turned to the shorter his colleague Igor and smiled.

“Bigger crowd than last year, yes? Than last year?” Igor said, twirling his uneven mustache.

“Last year wasn’t as big a deal. Oop… here we go.”

Igor crossed the dark room to peer out the window as well, standing carefully back from it. Outside, the number 150 was blazoned on just about everything banners, on signs, on balloons, and capes [be specific to create a better mental picture for the reader]. One hundred fifty years since the Great Tomes revealing the Builders had been discovered.

Nathan then goes on to discuss vagueness, and how important specific details are in allowing the reader to “see” the scene.

I would not think about this in terms of vagueness versus specificity, though that’s a perfectly legitimate way of viewing it.

I would think of this as a reluctance to write description. I’m not sure why, but a good proportion of all the workshop entries and so on that I’ve seen have this precise failing. The writer does not describe the scenery, and thus does not draw the reader into the opening scene.

There is, I suppose, a fine-ish line between setting the scene and stalling the action with so much description that the reader wonders if anything is ever going to happen. Remember, however, that the point-of-view protagonist is IN the scene and that all description is from his or her point of view. Thus, the initial description of the world is also part of characterization. Besides that, we can establish tension AND add in plenty of description at the same time. Here is one of my favorite third-person openings:

Bandits often lay in wait in the ruins of the old town at the fourways — Jenny Waynest thought there were three of them this morning.

She was not sure any more whether it was magic which told her this, or simply the woodcraftiness and instinct for the presence of danger that anyone developed who had survived to adulthood in the Winterlands. But as she drew rein short of the first broken walls, where she knew she would still be concealed by the combination of autumn fog and early morning gloom beneath the thicker trees of the forest, she noted automatically that the horse droppings in the sunken clay of the roadbed were fresh, untouched by the frost that edged the leaves around them. She noted, too, the silence in the ruins ahead; no coney’s foot rustled the yellow spill of broomsedge cloaking the hill slope where the old church had been, the church sacred to the Twelve Gods beloved of the old Kings. She thought she smelled the smoke of a concealed fire near the remains of what had been a crossroads inn, but honest men would have gone there straight and left a track in the nets of dew that covered the weeds all around. Jenny’s white mare Moon Horse pricked her long ears at the scent of other beasts, and Jenny mind-whispered to her for silence, smoothing the raggedy mane against the long neck. But she had been looking for all those signs before she saw them.

This is DRAGONSBANE by Barbara Hambly. We get the initial problem presented to us immediately, but we also learn a LOT about Jenny. We see that she is not terrified at the thought of bandits lying in wait, even though she is a woman and appears to be alone. We learn that she has some ability to work magic. But we are allowed to step into the scene because of the huge number of details Hambly works into these brief paragraphs. Not just about frost and broomsedge; we already have an idea what the world is like, because of the ruins, the need for people to learn caution and woodcraftiness, the reference to the old Kings, all of that.

If you are working with a first-person narrative or a very close third-person narrative, you may not put in so much description up front — if your pov protagonist isn’t looking at something, noticing it, thinking about it, then it doesn’t come up in the narrative. In that case, you depend more or the protagonist’s voice to draw in the reader. But you also add setting details, which also play a role in hooking the reader, like so:

Her name is Melanie. It means “the black girl”, from an ancient Greek word, but her skin is actually very fair so she thinks maybe it’s not such a good name for her. She likes the name Pandora a whole lot, but you don’t get to choose. Miss Justineau assigns names from a big list; new children get the top name on the boys’ list or the top name on the girls’ list, and that, Miss Justineau says, is that.

There haven’t been any new children for a long time now. Melanie doesn’t know why that is. There used to be lots; every week, or every couple of weeks, voices in the night. Muttered orders, complaints, the occasional curse. A cell door slamming. Then after a while, a month or two, a new face in the classroom — a new boy or girl who hadn’t even learned to talk yet. But they got it fast.

That’s from THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS by M. R. Carey, a story which depends almost entirely on the charm of Melanie’s voice to carry the reader through the story, and very successfully, too. This is one of the closest third-person points of view I’ve ever read, acting a great deal like a first-person narrative.

We get a lot of weird details in just these few words, even though there is no camera panning across the scene. This sets up a tremendous urge to keep reading in order to find out what kind of world this is, with its children brought in at night — children who haven’t learned to talk yet — and locked into cells and given names off a list. Melanie’s voice is so bright and chipper and entirely undisturbed by the extremely weird life she is living; the contrast between her attitude and the situation creates tension and acts as another hook.

Here is a real first-person opening:

It was a dumb thing to do, but it wasn’t that dumb. There hadn’t been any trouble out at the lake in years. And it was so exquisitely far from the rest of my life.

Monday evening is our movie evening because we are celebrating have lived through another week. Sunday night we lock up at eleven or midnight and crawl home to die, and Monday (barring a few national holidays) is our day off. Ruby comes in on Mondays with her warrior cohort and attacks the coffeehouse with an assortment of high-tech blasting gear that would whack Godzilla into submission: those single-track military minds never think to ask their cleaning staff for help in giant lethal marauding creature matters. Thanks to Ruby, Charlie’s Coffeehouse is probably the only place in Old Town where you are safe from the local cockroaches, which are approximately the size of chipmunks. You can hear them clicking when they cantor across the cobblestones outside.

This is SUNSHINE by Robin McKinley, who I must say pulls off in this book one of the very best openings I’ve ever seen. This story that looks so much like it’s set in contemporary normal life until, on page ten or so, we suddenly take a left turn toward weird. Of course McKinley doesn’t wait till then to establish the tension; she sets up the tension in the first very short paragraph — what happened at the lake? — but mostly in these opening paragraphs we are setting the scene and establishing the protagonist. Once again we get a very clear picture of the protagonist right away — from her use of casual language: dumb, crawl home to die, whack Godzilla into submission, etc.

In my opinion, it’s harder — substantially harder — to establish a catchy first-person (or unusually close third-person) narrative voice than a more distant third-person protagonist as in DRAGON’SBANE. By harder, I mean of course harder for me, but my impression is that it’s also harder for most people.

But even if you are using first-person narration, you have to draw the setting right up front in order to allow the reader to step into your world. Coffeehouse, cockroaches, movie night, silly B-movies like Godzilla, massive cleaning equipment. We’re right there with Sunshine, we’re IN the story.

That’s what the writer should aim for.

March 7, 2015

Why was your book rejected?

So, everyone’s familiar with Teresa Nielson Hayden’s post “Slushkiller,” right?

Here is the part I’m interested in at the moment:

Manuscripts are unwieldy, but the real reason for that time ratio is that most of them are a fast reject. Herewith, the rough breakdown of manuscript characteristics, from most to least obvious rejections:

1.Author is functionally illiterate.

2.Author has submitted some variety of literature we don’t publish: poetry, religious revelation, political rant, illustrated fanfic, etc.

3.Author has a serious neurochemical disorder, puts all important words into capital letters, and would type out to the margins if MSWord would let him.

4.Author is on bad terms with the Muse of Language. Parts of speech are not what they should be. Confusion-of-motion problems inadvertently generate hideous images. Words are supplanted by their similar-sounding cousins: towed the line, deep-seeded, dire straights, nearly penultimate, incentiary, reeking havoc, hare’s breath escape, plaintiff melody, viscous/vicious, causal/casual, clamoured to her feet, a shutter went through her body, his body went ridged, empirical storm troopers, ex-patriot Englishmen, et cetera.

5.Author can write basic sentences, but not string them together in any way that adds up to paragraphs.

6.Author has a moderate neurochemical disorder and can’t tell when he or she has changed the subject. This greatly facilitates composition, but is hard on comprehension.

7.Author can write passable paragraphs, and has a sufficiently functional plot that readers would notice if you shuffled the chapters into a different order. However, the story and the manner of its telling are alike hackneyed, dull, and pointless.

(At this point, you have eliminated 60-75% of your submissions. Almost all the reading-and-thinking time will be spent on the remaining fraction.)

8.It’s nice that the author is working on his/her problems, but the process would be better served by seeing a shrink than by writing novels.

9.Nobody but the author is ever going to care about this dull, flaccid, underperforming book.

10.The book has an engaging plot. Trouble is, it’s not the author’s, and everybody’s already seen that movie/read that book/collected that comic.

(You have now eliminated 95-99% of the submissions.)

11.Someone could publish this book, but we don’t see why it should be us.

12.Author is talented, but has written the wrong book.

13.It’s a good book, but the house isn’t going to get behind it, so if you buy it, it’ll just get lost in the shuffle.

14.Buy this book.

This is a classic post and rather inspirational, really, since hopefully you will be able to decide you’re not in the first 75% of all manuscripts and this conviction can give you a lift. Incidentally, if I’m tired, I can perfectly well type something on the order of “A shutter went through her body.” I normally catch this sort of thing almost immediately after I type it, but not always.

I typed “Cypress” instead of “Cyprus” twice in one of the Black Dog short stories and didn’t notice for an amazingly long time. It happens. That is why you proofread. Also why you get someone else to proofread.

9, 10, and 11 would probably be harder to spot. I mean, it’d be harder to spot it if your own manuscript fell into one of those categories. I guess that’s one of the things that analytical, honest beta readers are for, if you can find one.

I’m not sure what 12 even means.

But hey, at least if you know you’re not in categories 1-8, you can hope you’re in 13 or 14.

On the other hand, here is another recent post by Ruth Harris on the same topic — a post that gives us a different (but also eye-opening) look at what goes on behind the scenes when publishing houses are making acquisition decision.

Ruth Harris is a bestselling author published by Random House, Simon & Schuster and St. Martin’s. She was also an editor for a couple of decades at big and small publishing houses. Here is how she lays out rejections. I’m truncating every single entry; if you want to see Harris’s full comments about each item, click through.

0. The reasons for rejection start with the basics, i.e. the ms. sucks. Author can’t format/spell/doesn’t know grammar or punctuation. S/he is clueless about narrative, characterization, plotting, pacing, and can’t write dialogue. S/he has apparently never heard of paragraphing and writes endlessly long, meandering, incoherent sentences that ramble on like poison ivy. (Harris doesn’t put this in as a numbered item in her list, but I’m making it number zero.)

1) Inventory Glut. We already have too many (insert your genre) and need to publish down the inventory so we’re not buying any of that particular genre.

2) P & L Blues. The P&L is the Profit And Loss projection publishers make for every book under consideration. … If the bottom line flashes red, you can guess what will happen next.

3) The Sales Whisperer. The Sales Department/Distributor just informed us that chick lit/gothic romance/space opera “doesn’t sell” any more. Sorry.

4) Mood Swings And Irrational Bias. The boss, editor-in-chief, head of Promo, hateshateshates the title/setting/subject for no logical reason.

5) Genre clash. We as a house excel with romance but are duds when it comes to science fiction. Maybe the buyer at a big distributor—or our Sales Manager, Editor-In-Chief, Marketing Director, CEO—doesn’t “get” (insert your book/genre). (Harris points out that you DO NOT WANT a publishing house that basically doesn’t understand fantasy to make an exception and buy your fantasy, because they’re likely to screw it up. I’m not quoting that bit here, but she’s all “Pop the champagne when you get that rejection.”)

6) Secret Agents / Agent Secrets. You love your agent but we don’t. Maybe there was a battle over contract terms that went off the rails. Perhaps we think the agent in question was double dealing, used us to bid up a price, or shafted us in some other way.

7) $$$$. The company’s in a cash crunch. Of course we’re never going to admit that (and our bosses might not even tell us) but we’ve been instructed to hold off on buying anything. Nada. Not right now and maybe not for the foreseeable future. Not until said crunch passes and the money’s flowing again.

8) Corporate Convulsion. A major “reorganization” has taken place. Maybe the whole company has been bought/sold/merged. Maybe the decision has come from somewhere Up There in Corporate. Anyway, half the staff (at least) has been fired. … if you, your book or genre remind the New Guys of the Old Guys, you’re going to get rejected.

9) We blew it. Sometimes editors and publishers are just plain wrong.

10) You’re a PITA. Once in a while, rejection is actually personal. We’ve published you before or a friend at another publisher has and we know from experience (or the grapevine) that you’re a whiny, nasty, demanding, narcissistic, high-maintenance PITA. No one wants to take your phone calls and everyone who’s had the misfortune of working with you hates you.

I love this list because of the contrast it gives to Slushkiller. First Hayden lays out problems with the manuscript; then Harris lays out behind-the-scenes issues at the publishing house. Between the two of them, surely we get a pretty complete list of the Reasons For Rejection.

Obviously, the reasons Harris lists are not under the writer’s control. Except for (10), of course, but I trust most people are not like that. Also, I should mention that Harris specifically mentions that rejection is not the end of the line anymore, because of self-publishing. There are some interesting examples of self-publishing success stories in the post and comments.

However, all of this can be recast a bit to meet the new reality of self-publishing / traditional publishing. And by “new reality,” I mean the way it is this week; who knows what the crazy world of publishing will be like in five years? But still:

Plainly it would be a good idea to clear the hurdles Teresa Nielson Hayden laid out before you self-publish OR before you send your manuscript to an agent.

You need to do your best to avoid bad agents. I notice that MY agent is listed as Recommended at Preditors and Editors, which is the site I just linked to.

Then it is your agent’s job, not yours, to be aware of and sort out the kinds of issues Harris lays out. That is one of reasons you benefit from having an agent.

Anyway, both Slushkiller and Harris’s post are fun to read and definitely informative.

March 6, 2015

Costume redesign for woman characters, and thoughts about targeting specific readers

Over at Muddy Colors — link from tor.com — a long post featuring a lot of comics and game characters in redesigned costumes.

I like this post, and I love a lot of the redesigned costumes, though I must say, not all of them. Personally, I’ll go for a sleek costume, a practical costume, or a costume with gravitas, any of the three, over a clunky or too-casual look. Samus (Metroid), for example: too clunky. The Scarlet Witch: way too casual. Mind you, I’m not the least bit familiar with either character, so for all I know, these redesigned costumes totally fit the characters. I just don’t care for them.

A costume with gravitas: Phoenix from The X-Men

A character whose expression and attitude were never, ever suited to the bikini look: Niriko from Heavenly Sword. Seriously, it’s hard to see how the original artist could give her that attitude AND put her in a bikini at the same time. The screen should have exploded.

Click on the images to blow them up.

I will add, if it’d been me, I’d have invited male artists to contribute. I get that this is about costumes-by-women-for-women, but still. I can’t imagine that every male artist ever thinks those spandex-thong-bikini costumes are the best thing ever.

I don’t think it’s actually true that those bikini costumes are designed for “the male gaze.” I think they’re designed specifically for what marketing departments think is going to appeal to the teenage male gaze. You do see a lot of art like this at SFF conventions, and it makes me roll my eyes SO HARD. But I expect a lot of men also roll their eyes, if only because the spandex-bikini thing is so horrifically impractical. Perhaps a second post for covers redesigned by male artists who are not being pushed toward bikinis by marketing departments?

Incidentally, it’s pretty obvious that in publishing, marketing departments don’t just pander to the male gaze. Is there a single modern romance cover where the guy has his shirt on?* And there are plenty of horrible Barbarian Warrior covers, too. This —

— is just as ridiculous for a guy with a sword as a bikini is for a woman with a sword. My God, people, don’t you know how unpleasant belly wounds are?

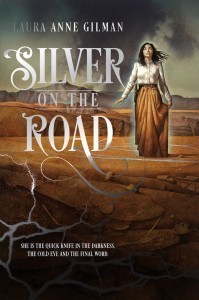

Also, either the pushback from female (and male) readers or something seems to be having an effect on marketing decisions for SFF novels, if perhaps not yet for comics or games, because check out this cover for Laura Anne Gilman’s forthcoming SILVER ON THE ROAD:

That is a nice cover. It’s by John Jude Palencar. I know that novels are not the same as comics, but I wonder how Palencar would have redesigned Red Sonja? The cover copy strongly implies that this fantasy novel includes a romance. Now the Territory’s Left Hand, Isobel takes to the road, accompanied by the laconic rider Gabriel, who will teach her about the Territory, its people and its laws. Yeah, “laconic” is clearly a code word for “romantic male lead.” Yet Palencar did NOTHING to sexy up this cover. I like landscape-heavy covers and don’t care for sexy covers, so this is a book I would pick up off the shelf if I happened to be browsing.

Covers are meant to sell books. Or comics, or games. I get that it would probably be less efficient for marketing people to scramble their signals so that it is harder to know at a glance whether a book is paranormal romance or historical fantasy, though in fact I find it remarkable that readers browsing the shelves (or browsing online) ever notice any new UF release if the cover blends into the horde of sexy-woman-with-sword-and-animal covers. Romance covers are even worse, since they all feature the same shirtless-dude-with-languishing-woman.*

I get that marketing people are not going to put the same cover on a product expected to draw primarily teenage male readers, or on a book aimed mainly at women, as they do for a historical fantasy meant to appeal to a broader audience. I get that women are (often) going to roll their eyes at the bikinis, that men are going to (often) be turned off by the shirtless wonders* on romance covers, and that marketing departments won’t care about either reaction if in general their product will sell significantly better with standard types of covers on them.

But I expect that anything marketing can do to make their titles stand out of the herd can only help visibility, even if it means giving up some of the signaling value of the standard cover tropes. At least, I wish they would try. At least to the extent of stopping with those asinine bikinis.

If you have time to click through and check out the costume redesigns, I hope you will comment. Especially if you’re a guy.

*I know perfectly well that some romance covers feature men with their shirts on. Please don’t take the time to point that out.

March 5, 2015

Predictability and the reading experience

Merrie Haskell recently asked on Twitter why we criticize a book if the plot is predictable. That caught my eye because of course I recently took THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS off my list of possible Hugo nominees even though I loved it, mostly because of the highly, highly predictable plot (and a little bit because of the clichéd characters).

Incidentally, if any of you have read this, did you find the plot so entirely predictable, almost to the point of being able to write the entire back third of the book yourself? Minus a handful of details, sure, but basically?

The reason this is interesting is because as soon as Merrie Haskell commented about this, I immediately thought of the kind of story where predictability is simply not an issue.

I mean, is there anybody here who did not know exactly how Laura Florand’s ONCE UPON A ROSE was going to turn out? Basically how every main detail was going to fit into the plot, the role every important character was going to play, all of that?

Yet in Florand’s book, this is fine. Because being astonished by the plot is not the point of a romance, at all. (Can anybody think of a counter example? That worked?) It’s a lot like those old-fashioned formulaic detective shows such as “Murder, She Wrote,” where not only the basic formula but also the pacing is entirely predictable. Of course that show was enormously popular, too. Romances are super-popular, formulaic detective shows are super-popular; obviously being predictable is a feature, not a bug, for a lot of people who enjoy these forms.

I suspect this is because:

a) Readers (and viewers) generally prefer that The Hero behave heroically, intelligently, and effectively. If you like The Hero, then watching him (or her) get the better of the bad guy is the whole point. I always liked Horatio in “CSI: Miami” back when I actually had time to watch tv. “House” was very formulaic, but I didn’t mind a bit.

b) If you know how the plot is going to work, where the beats will fall, how the pacing will work, then you are free to appreciate the detail work because you don’t feel driven to turn the pages as fast.

c) If you don’t have to worry about the ending, then the reading (or viewing) experience is low stress, also allowing you to take your time turning the pages and enhancing the experience, provided that’s what you were in the mood for when you picked up the book or turned on the tv.

What is crystal clear to me after trying various romances and being almost completely unengaged, and then finding several authors whose work I like very much, is that predictability is not a problem for me — but only if the writing is good enough. I need the characterization and actual sentence-by-sentence writing to be really well done if a romance is going to work for me, and the more contemporary the setting, the more true that is. Whereas I have found that as long as the dialogue is good, then other aspects of the writing can be somewhat clunky and the book can still work for me — but only if the plot is less predictable.

I wouldn’t even say that books that are extremely well written and also offer thoroughly unexpected plot twists are “better” than those that just do the former and not the latter. Contrast Andrea K Höst’s AND ALL THE STARS with Laura Florand’s ONCE UPON A ROSE. The former is a save-the-world SF story with a romance included. The latter is a contemporary romance, straight up. The former offers an amazing plot twist that will knock your socks off. The latter is entirely predictable as far as the broader elements go. Both offer an excellent reading experience. You can’t easily say that one is better than the other, but only the latter works as, say, bedtime reading. The former would keep you up late going “BUT WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN?” and obsessively turning pages. The latter is like snuggling with a warm puppy.

So. You downgrade a story to the extent that it’s supposed to be a page turner, but its predictability gets in the way of the tension. Though I greatly admire an author who pulls off An Amazing Plot Twist, if it’s not supposed to be that kind of story, then predictability can in and of itself be a virtue rather than a problem.

Or so it seems to me.

March 4, 2015

#TotallyNotFantasy

Okay, this is funny: Michael Underwood has a post up at Geek Theory.

See, a few days ago, Kazuo Ishiguro defended his new book The Buried Giant by declaring that it is certainly not fantasy — it just uses fantasy tropes to explore deep issues.

As you can imagine, this assertion raised some hackles. The post at Geek Theory collects a bunch of tweets responding to Ishiguro. Lots of them are delightfully snarky:

Scott Lynch: Why no, this novel isn’t fantasy. It contains psychology and allegory and stuff like that, you see.

Elizabeth Bear: You’re secretly writing economics texts disguised as rollicking adventure fantasy capers.

That one particularly made me smile, because did you happen to ever read F Paul Wilson’s An Enemy of the State? It is totally an economics text disguised as an SF novel.

Anyway, Steven Brust: My work is #TotallyNotFantasy. It is …I mean the magic…the story reflects…just shut up. It isn’t.

Martha Wells: In my writing the shapeshifting lizard people are #TotallyNotFantasy – they’re metaphors for like, sex and issues and important stuff.

And so on. You should click through and enjoy lots more.

Of course, as Michael Underwood points out, this “It’s totally not fantasy” thing has been around for a good long while. Look at Atwood.

Ursula K LeGuin has a post up about this as well, at Book View Café.

I see, btw, that some people are defending Ishiguro by saying he didn’t really mean to imply that fantasy is trash, unlike real writing which is ART. I dunno. To me, it sure sounds like that is exactly what Ishiguro meant:

Ishiguro: “I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he said. “Will readers follow me into this? Will they understand what I’m trying to do, or will they be prejudiced against the surface elements? Are they going to say this is fantasy?”

Yeah, wouldn’t want the Readers That Matter to mistake your beautiful allegorical novel for fantasy. God forbid.

But the tweets are fun. I’m sorry I missed this hashtag while it played out in real time.

And btw, MY BOOKS are #TotallyNotFantasy. They’re about loyalty and trust and love and family and all that stuff that has to do with real human relationships. Totally literary, really! The dragons are just surface elements.