Rachel Neumeier's Blog, page 319

December 4, 2015

Fat Fantasy Wordcounts: A second look

So, fat fantasy wordcounts.

As I mentioned some time ago, Fantasy Faction checked out the wordcounts of five “fat fantasy” series. Then SarahZ pointed out that all these series are by male authors – well, five series and one single book, I suppose the first book in another series, which I had not even noticed in my quick glance at the post.

Five is not a lot, six is also not a lot, but Sarah is right that one does wonder how the writer of that post chose which series to examine. What were the criteria by which a fantasy series was identified as a “fat fantasy” series? To me, the term seems faintly derogatory, though plainly the author of the Fantasy Faction post didn’t mean it that way or he would surely not have chosen The Lord of the Rings as an illustration of fat fantasy wordcounts. So, then, why those particular series? I suspect he just picked the first several fat fantasy series he came to when he glanced over his shelves.

I don’t know, but I got curious and thought I’d take a few minutes (it was actually a pretty tedious couple of hours) to estimate the wordcounts for another handful of fat fantasy series, these by women, and compare them to:

a) the wordcounts from Fantasy Faction’s selections, and

b) the wordcounts of normal-length fantasy.

Arbitrarily defining “normal length” as “in the general neighborhood of my own typical wordcount,” I checked the wordcounts for all my books that are actually on the shelf. They range from a low of 82,000 words (The City in the Lake) to a high of 125,000 words (Land of the Burning Sands and Black Dog). The mean for all eight is 112,000 words. I hereby declare that 112k plus or minus 20k is “normal length” for fantasy. Incidentally, the wordcounts for all of my unpublished but completed novels are on the high side of this length, so those would shift the average, but whatever, I just wanted a general idea of wordcounts for non-fat fantasy.

Then I looked at a bunch of fat fantasy novels. But first I had to decide what counts as “fat fantasy.” I don’t want to use the term interchangeably with “epic fantasy,” so I arbitrarily decided that any fantasy series could be included if it met the following criteria:

a) At least five four books in the series. There was a four-book series I particularly wanted to include, so I redefined the criteria halfway through. Hey, it’s my list.

b) All or most of the books in the series seem longer than average when you look at them on the shelf.

I’m sure you already know how that page thickness, line spacing, and font size can be different for different books. Most hardcover YA books today seem to be practically double-spaced compared to older books, and with bigger fonts, too. But I bet you didn’t know how EXTREMELY variable pages per inch of thickness and the number of words per page can be. I sure didn’t, until I looked at some of the books on this list. Kushiel’s Dart looks like it takes up about the same amount of space on the shelf as Kushiel’s Chosen, but it is 225 pages longer, or about a quarter again as long.

c) The series is epic, not episodic. It’s not “another installment of the adventures of whoever.” An epic feel to a series seems to me to be implied by the term “fat fantasy.”

So, then here are the five fat fantasy series by women that I pulled off my shelves, in alphabetical order by author. For some books, I could get the actual wordcount via Amazon. For others, I had to estimate the wordcount.

It turns out that Amazon used to offer “Book Stats” as part of their “Inside the Book” feature. They no longer do. But you can get to the statistics for some books by the following means:

Go to the Amazon site. Search for a particular book. Click on that book. Now go up to the search bar. See where it says “dp/”? Delete everything after that and then type in sitb-next/ in between the dp/ and the 10-digit ISBN number.

For Kushiel’s Dart, the original search bar will read:

http://www.amazon.com/Kushiels-Dart-L...

And after you adjust it, it will read:

http://www.amazon.com/Kushiels-Dart-L...

Hit enter. Poof! You are now on the Book Stats page for Kushiel’s Dart.

Let me repeat that this does not work for all books. It seems to work mainly for older titles, and not all of those.

If I couldn’t get the wordcount via Amazon, I estimated it. I looked inside-the-book on Amazon to estimate wordcounts. For example, for Ship of Magic by Robin Hobb, which is 832 pp, I counted the number of words per line for five lines. The average was 11 words. I dropped this to 10 because not all lines are complete. I counted the number of lines per page, which was 39. This suggests that there are about 390 words per page, which is surely an overestimate because not all pages are complete, either, so I called it 380 words per page. Given the book is 832 pp long, this would be about 316,000 words, which is humongous. Even if I am still overestimating the wordcount for this book, it must be around 300,000 words.

Using this method with my own books, where I could check accuracy of estimations, I found that I was generally within 3% of the correct wordcount (but off by a lot in one case). When I was off, it could be either way — an overestimate or an underestimate. So take estimates below as plus-or-minus at least 3%.

1. Jacqueline Carey

— Kushiel’s Dart . . . 276,706 words. That sucker is 912 pages. Talk about fat fantasy! Incidentally, that means there are about 300 words per page.

— Kushiel’s Chosen . . . 241,878 words, even though it is a mere 687 pages. That’s 350 words per page. If you think that’s quite a difference from the first book, just wait!

— Kushiel’s Avatar . . . 263,039 words, clocking in at 750 pages, 350 words per page.

— Kushiel’s Scion . . . 260,216 words, 976 pages, 270 words per page.

— Kushiel’s Justice . . . 244,310 words, 912 pages, 270 words per page.

— Kushiel’s Mercy . . . not listed, but one can guess based on the others: it’s 672 pages, which probably means 350 words per page, which would put it at about 235,000 words.

That is 1M 500k words for the six books in this pair of tightly linked series.

And then there’s the connected Naamah series and perhaps others that are also linked.

Look how the number of words per page ranges from about 270 to about 350! Did any of you realize how much the wordcount per page could vary? I really did not, even though I knew line spacing and font size differs quite a bit from book to book. If you look at wordcounts per page in other series, you will find that the range actually is from a low of around 270 to a high of about 470. In the densest books, there are more than 40% more words per page! Can you believe that?

Okay, moving on:

2. Robin Hobb

— Ship of Magic . . . The wordcount is not available, but the book is 832 pages. Estimating as given above, we see that the wordcount may be around 315,000.

— Mad Ship . . . 864 pages, something in the neighborhood of 320,000 words.

— Ship of Destiny . . . 800 pages, or roughly 300,000 words

— Dragon Keeper . . . a sharp decline to 493 pages and perhaps 186,000 words. Does that still count as fat? Well, it’s still longer than most of the books I’ve written.

— Dragon Haven . . . 544 pages, or about 206,000 words.

— City of Dragons . . . 334 pages, or a mere 125,000 words, and now I think we are out of the region of fat fantasy.

— Blood of Dragons . . . 448 pages, or something like 170,000.

That is 1M 340k words for the seven books belonging to this pair of loosely linked series.

3. Juliet Marillier

— Daughter of the Forest 206,732 words, 560 pages, 370 words per page

— Son of the Shadows 200,653 words, 464 pages, 433 words per page

— Child of the Prophecy 214,481 words, 608 pages, 350 words per page

— Heir to Sevenwaters . . . not listed, 416 pages. Splitting the difference for her earlier books and assuming 370 words per page, that would be 154,000 words

— Seer of Sevenwaters . . . not listed, 448 pages, or perhaps around 166,000 words

— Flame of Sevenwaters . . . not listed, 448 pages, or again 166,000 words

That would be 1M 107k words for these six books.

4. Elizabeth Moon

— Deed of Paksennarion, Divided Allegiance, Oath of Gold . . . 509,577 for the entire trilogy, 1040 pages, so if you divide the wordcount up evenly, that’s only 170,000 words per book, and about 350 pages per book. On the other hand, there seem to be a whopping 490 words per page. Wow.

— Surrender None, Liar’s Oath . . . 377,223 words put together, 864 pages. That’s about 188,000 words apiece, still a high 430 words per page, about 432 pages each, so the books are getting longer.

— Oath of Fealty . . . the wordcount is not listed, but the book is 585 pages. I estimated about 400 words per page, which seems to be conservative given the per-page wordcounts for the omnibus versions. We are definitely in fat fantasy territory here, with the book coming in at roughly 230,000 words.

— Kings of the North . . . 512 pages, or close to 200,000 words

— Echoes of Betrayal . . . 496 pages, or close to 200,000 words

— Limits of Power . . . 512 pages, or close to 200,000 words

— Crown of Renewal . . . 512 pages, or once more close to 200,000 words

That is 1M 900k words for these ten books.

5. Sherwood Smith

— Inda . . . 624 pages, an estimated 380 words per page, which would make it about 230,000 words

— The Fox . . . 784 pages, around 275,000 words

— The King’s Shield . . . 704 pages, something like 244,000 words

— Treason’s Shore . . . 784 pages, around 271,000 words

That is 1M 20k for these four books.

6. Michelle West

— The Hidden City . . . 768 pages, about 450 words per page, an estimated 350,000 words.

— City of Night . . . 560 pages, about 250,000 words.

— House Name . . . 736 pages, about 331,000 words.

— Skirmish . . . 672 pages, about 302,000 words

— Battle . . . 785 pages about 353,000 words

— Oracle . . . 688 pages, about 309,000 words

1M 895k in six books.

Now, let’s compare that to the Fat Fantasy series wordcounts provided by Fantasy Faction. That will give us six epics by male authors and six by female authors. Let me summarize all the series here:

Lord of the Rings – J. R. R. Tolkien: 473k in three books, or an average of 157,000 per book.

Wheel of Time – Robert Jordan: 3M 304k in eleven books, or an average of 300,000 per book.

Stormlight Archives – Brandon Sanderson: 387k in just one book.

A Song of Ice And Fire – George R. R. Martin: 1M 314k in four books, or an average of 328,000 per book.

Malazan Book of the Fallen – Steven Erikson: 3M 325k in ten books, or an average of 332,500 per book.

The Dark Tower – Stephen King: 1M 295k in seven books, or an average of 185,000 per book

Kushiel series – Jacqueline Carey: 1M 500k words in six books, or an average of 250,000 per book.

Liveship/Dragon series – Robin Hobb: 1M 340k words in seven books, or an average of 191,000 per book.

Sevenwaters series – Juliet Marillier: 1M 107k words in six book, or an average of 184,500 per book.

Paksennarion series – Elizabeth Moon: 1M 900k words in ten books, or an average of 190,000 per book.

Inda series – Sherwood Smith: 1M 20k in four books, or an average of 255,000 per book.

Housewars series – Michelle West: 1M 895k in six books, or an average of 315,800 per book.

Observations:

If anyone doesn’t belong in this list, it’s Tolkien. His books are decidedly the shortest, though it seems a bit strange to refer to an average length of 157k as “short.”

Authors who break 200k per book include four of the guys and three of the women, so no real difference there.

Authors who break 300k per book include the same four of the guys and just one of the women. Of course it’s impossible to say whether there is actually a tendency for fat fantasy by men to be longer than fat fantasy by women, because this is a small sample of authors, not to mention selected practically at random. I got all but one of these series by female authors by going downstairs and looking around for fat fantasies with female authors, except for Michelle West’s series, which I selected because commenters mentioned her in the context of fat fantasy. Female authors predominate in my personal library, so it wasn’t hard to find some appropriate series. Even though Smith’s Inda series only includes four books, I particularly wanted to include it because I knew the books were quite long

Still, given this particular set of authors, the average length for the male authors is 280,500 words per book. The average length for the female authors is 224,600 words per book, or about 56,000 words less. Even if this difference is real and not merely a statistical artifact, which is far from clear, it’s hard to say what it might mean.

Let me just add one thing: authors are told all the time that you shouldn’t plan to go much above 100,000 words, maybe up to 150,000 words for fantasy. Obviously a whole lot of epic fantasy authors are going way, way, above that. Some are managing to do that with their debut novels. But . . . even so. I strongly suspect that your chances of breaking into traditional publishing are much better if you aim for something in the close neighborhood of 100,000 words. Check out this post. Particularly note the information about Throne of Glass by Sarah Maas. I found this particularly interesting given Aimee’s comment about Throne of Glass in yesterday’s post.

December 3, 2015

Horses in fantasy films

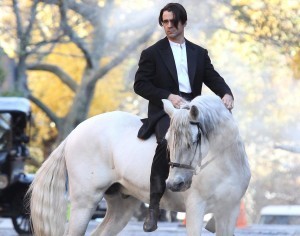

A post at tor.com: Galloping Straight Into Our Hearts: The Greatest Horses of Fantasy

They don’t mean “The greatest horses in fantasy.” They mean, “The greatest horses in fantasy *films*. Which is fine, but I’m just saying, you aren’t going to see Bansh from Range of Ghosts here.

But still! Pretty horses!

Yes, yes, you can hardly beat the Frisian in “Ladyhawk.”

The horse that’s missing that I immediately thought of: The white Andalusian from the movie adaptation of “A Winter’s Tale.”

This horse was clearly trained in classical dressage. Lovely animal. I love Andalusians anyway.

December 2, 2015

Ah, the Goodreads Choice Awards

If it’s a massive popularity contest you aim for, then the Goodreads Choice Awards is ideal. I dunno, I think in general I am most interested in the results of awards like the World Fantasy Award, which has a panel of judges; or the Nebula, which requires nominations to come from professional writers. In other words, not wide-open popularity contests. On the other hand, there’s a place for pure popularity too, obviously, and it was really quite interesting seeing what got nominated in all the Goodreads categories.

Of course I read mainly books that have been recommended by bloggers I follow and Goodreads reviewers I follow and so on, so these awards don’t much matter to me — no awards matter to me in that sense — but still, interesting to see what’s shuffled up to the top of the heap for 2015.

I don’t know that much about many of the categories, but here are the SFF winners and runners-up, conveniently provided by File 770.

Best Science Fiction

Winner: Golden Son, Pierce Brown, 32,225 votes

Seveneves, Neal Stephenson, 15,710 votes

The Heart Goes Last, Margaret Atwood, 14,147 votes

The winner of this category obviously smashed the competition, getting about twice as many votes as the second-place novel. I hadn’t read any of these three, in fact. I voted for Ancillary Mercy, which I loved and which got about 1/4 as many votes as the winner. I see that the range of votes was from 32,000 all the way down to less than 1000 for KSR’s Aurora. Interesting.

Best Fantasy

Winner: Trigger Warning, Neil Gaiman, 33,681 votes

A Darker Shade of Magic, V. E. Schwab, 30,530 votes

Shadows of Self, Brandon Sanderson, 18,171 votes

Obviously the voting was much closer between the top two choices here, then again a very sharp dropoff. Again, I haven’t read any of these. I voted for The Fifth Kingdom by NK Jemisin, which I admit I haven’t read. I voted for it on the strength of her earlier titles.

Best Horror

Winner: Saint Odd, Dean Koontz, 17,644 votes

Alice, Christina Henry, 11,845 votes

The Last American Vampire, Seth Grahame-Smith, 10,336 votes

We can sure see that Horror doesn’t have as extensive a fan base as SF or Fantasy, can’t we, since the winner here picked up only about half as many votes as the winners of the above categories. I haven’t read any of these either, but I voted for Saint Odd because I definitely have liked other books in this series, which imo represents some of Koontz’s best work. I need to read the Odd Thomas book before Saint Odd before I can finish the series. Hopefully pretty soon.

Best Young Adult Fantasy & Science Fiction

Winner: Queen of Shadows, Sarah J. Maas, 35,770 votes

Carry On, Rainbow Rowell, 29,569 votes

Winter (The Lunary Chronicles #4), Marissa Meyer, 28,418 votes

Interestingly, Novik’s Uprooted was included in this category. That’s what I voted for, of course. I can see the book as YA, but I believe it was marketed as adult, and I wonder how much that hurt it in this awards contest?

I have to admit, I am 100% not interested in Carry On. I loved Fangirl, but the part of Fangirl I was not interested in was the Simon Snow excerpts. I thought Simon seemed like a boring, unintelligent, unperceptive twit. Obviously a lot of readers were indeed interested in the spin-off title, though.

I will never understand the attraction of the Lunary Chronicles. I listened to the first one and about 3/4 of the second and honestly, no. Talk about boring, unintelligent protagonists. I just do not like this series.

I’m impressed that Sarah J Maas managed to win this category even though her votes were divided up between two different titles. I haven’t yet read anything by her, but maybe eventually. So many older titles on my TBR pile, I don’t know.

Other categories: I’m pleased to see that Gray didn’t win the Romance category. I’m a bit disturbed to see that Go Set a Watchman won the fiction category; honestly, I think there are significant doubts about whether Harper Lee truly was okay with publishing this book and it bothers me. I would have liked to see Ravensbruk win the history category, given this review by Maureen at By Singing Light. I voted for it on the basis of that review. But of course the actual winner (Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania by Erik Larson) might be superb.

Most interesting discovery from this year’s Goodreads Choice Awards: Did you know there was a spinoff novel series featuring Veronica Mars? I didn’t. The second book, Mr Kiss and Tell, was a nominee this year. The first book, The Thousand Dollar Tan Line, was published last year, though I didn’t hear about that. It’s set after the movie, which in fact I just watched and liked quite a bit.

December 1, 2015

Personally, I suspect true AI is impossible

Which may just go to show that I also find the notion of true AI kinda disturbing.

Nevertheless, here is a post by Jim Henley at Unqualified Offerings: Fermi Conundrum Redux: The Singularity as Great Big Zero?

So if Strong AI civilizations exist, they should be here too. And they’re not. Which has to make one suspect they don’t exist and can’t. One possible answer to Fermi’s Conundrum has always been that organic intelligence has evolved, but that interstellar travel just isn’t practical for biological life forms. But if biological life forms can develop Strong AI, then that screen shouldn’t hold. So if there are other organic intelligences in the universe – we of course can’t know – then Strong AI may not be possible at all.

Which, as I say, is basically fine with me.

But the bit of the post that actually caught my eye was here (bold mine):

[S]o maybe no one will demand answers to the question of On what basis can you say Strong AI is impossible since human intelligence is just computation huh huh huh? But if they did, my answer would be that I have no idea but so what? Before one can say why no humans are ever born who float free of the Earth like talking balloons, we first notice that, in fact, no humans are ever born this way. In the case of a Fermi-type conundrum, we first notice the lack of things we should see if they exist, and only afterward turn to questions of why they might not exist. But first we notice the lack of things.

Because I was all: Wait, is anybody out there actually maintaining as a serious thing that human intelligence is just computation?

Wow. Okay, buddy, keep working on that purely computational artificial intelligence project of yours. Let me know how that works out for you.

Another unusual dessert: Passion Fruit Fool

I wanted to share this dessert with you, too, because it’s unusual and good and also very easy.

Mine didn’t quite like the above because I didn’t have any fresh passion fruits, so I couldn’t drizzle actual passion fruit pulp across the top, which would make a nice garnish but is certainly not crucial.

Passion fruit tastes something like apricots and a little like peaches and different from either. I like it a lot and will definitely be picking up more passion fruit puree when I get the chance. You can drink the sweetened juice and that’s good, too, but using pureed passion fruit in a dessert like this will make it go a lot farther. So, here you go:

Passion Fruit Fool

14 oz pkg frozen passion fruit puree, such as this kind, which is pure passion fruit puree with no additives or sugar or anything. I got this at Global Foods; if you have a good global grocery store, check in the frozen aisle.

1 1/2 C sugar, or more to taste, divided because you are going to add some to the passion fruit puree and some to the cream.

1 Tbsp or so cornstarch

2 1/2 C heavy cream

1 fresh passion fruit, optional

Stir 2/3 C of sugar into the thawed puree. The puree I was using was very thin, like water, even after adding the sugar. I wanted it more like syrup, so I brought it to a low boil, added a slurry of cornstarch and water, and stirred for two minutes or so, until the puree had thickened. I’m not sure how much cornstarch I added, so the above is a guess. You probably already know that you must mix cornstarch with about an equal amount of water before you add it. You drizzle it into your simmering fruit puree while stirring, then continue to stir and cool until the puree has thickened, which as I say takes only a couple of minutes.

Pour the thickened puree into a bowl or jar or whatever and chill until cold.

Now whip the cream until stiff. Gradually add the remaining sugar while whipping the cream, starting with 1/3 C but adding up to 1/2 C additional sugar after that, or even more. I usually add 1/4 C of sugar to 1 C of heavy cream, but you are probably going to want the cream sweeter than usual to contrast with the quite tart passion fruit syrup. At least, I did.

The cream is stiff when you can stop the beaters, lift them out, and the cream stands up in stiff little peaks where you lifted the beaters out.

Now, dollop whipped cream into small glass dessert dishes. Spoon over passion fruit syrup. Repeat. Repeat. Cut through the fool a couple of times with a knife to swirl.

If you happen to have a fresh passion fruit, split it and scoop out the seeds and drizzle a bit over each individual serving. Serve.

I find dishes of fool hold pretty well for 12 hours. But I don’t know about holding them longer. I assembled about a third of this recipe at a time to avoid needing to find out just how long it would hold.

November 30, 2015

Mimicry in plants: are we sure this isn’t an SF world?

This is quite amazing: a vine that mimics the leaves of the host tree it climbs. Of course, it’s a vine, so maybe it happens to clamber from one tree to another? No problem; it can mimic each tree in turn.

Endemic to Chile and Argentina, B. trifoliolata is the first documented example of a plant that exhibits mimetic polymorphism, which is the ability to mimic multiple different host species. Researchers found that when this vine was climbing a tree it was able to imitate the host leaves in terms of size, shape, color, orientation and even vein conspicuousness.

Mechanisms by which a plant might do this . . . um . . . you know, apparently this vine can mimic another plant’s leaves even when the vine is not actually in contact with the other plant?

???!!

You think you basically understand how plants work and then you get something like this. I doubt I’ll ever use this kind of mimicry in a story. No one would believe it.

I got the link via David Brin’s website Contrary Brin, by the way. He posted a lot of links to cool science things over weekend.

The Best Raspberry Cheesecake Pie

As it happens, no one in my family feels it is essential to have pumpkin pie for Thanksgiving. Turkey, yes. Pumpkin pie, not so much.

This pie is much fancier than pumpkin pie, but it’s not at all difficult. Also, it involves raspberries and cheesecake and chocolate, so it’s perfect for a party.

So here you go:

Layered Raspberry Cheesecake Pie

1 baked pastry pie crust. My mother’s good with pie pastry, so she made this for me.

3 Tbsp sugar

1 Tbsp cornstarch

8 oz fresh or frozen raspberries

8 oz cream cheese, softened

1/3 C sugar

1/2 tsp vanilla

1/2 C heavy cream, whipped

2 oz semisweet chocolate

3 Tbsp butter

Okay, if you need to bake the pie crust, do that.

Combine the sugar, cornstarch, and raspberries in a small saucepan. Bring to a boil over medium heat. Cook, stirring, for about 2 minutes. Pour into pie crust and set aside to cool.

Whip the cream.

Beat together cream cheese, sugar, and vanilla until fluffy. Fold in whipped cream. Spread over raspberry layer. Chill at least 3 hours.

Now, the chocolate, even with all that butter, will firm up too much if you put it on the pie and then chill the pie. This will make it hard to cut the pie. So ideally, you will do this next bit shortly before you serve the pie, like right before everyone sits down for dinner.

Melt the chocolate with the butter. Cool for five minutes. Spread over pie. I think it is pretty to leave a thin border of white showing around the edge of the pie, but that’s up to you. If you happen to have a single fresh raspberry sitting around, place this in the center of the pie as a garnish. You can chill the pie about two minutes in order to set the chocolate, although it will set anyway.

Serve within an hour or two and the chocolate will not have hardened too much.

If you chill the pie with the chocolate layer in place, then you can use a sharp knife to gently score the chocolate. Repeatedly score along a single line and you will eventually be able to get through the chocolate layer neatly, without squishing the cheesecake filling out the sides of the piece of pie. But you see why it’s easier to cut the pie before the chocolate gets too hard.

November 25, 2015

Specific feedback is something to be thankful for —

At Magical Words, Misty Massey explains how she and a couple of other writers did a panel called Live Action Slush.

Many, many times I hear writers complain how much they hate getting form rejections from editors, because such things do nothing to help them understand why the editor didn’t want to buy their story. . . . [In Live Action Slush], the writers submit the first pages of their novels anonymously. A designated reader reads each page aloud, and the three of us listen as if we were slush editors, raising our hands when we reach a place that would cause us to stop reading and move on to the next submission. Once all three hands are up, the reading stops and we discuss what made us stop reading.

That sounds like a pretty snazzy idea, although I’d sort of think agents and editors would be better than authors at this kind of thing. I think, from looking at a couple of her other posts, that Misty Massey is also an editor. Good, that sounds better.

As a related point, can you imagine Janet Reid participating in a panel like this? Well, maybe she does, sometimes. I expect she would not be quite so definitively shark-like in that kind of in-person situation. Though even in Query Shark, I don’t think she sounds brutal. Just clear.

Anyway. As always, it’s up to the author to decide how to handle the writing. But it does sound potentially useful to have experienced readers tell you, “Okay, this is where you lost me.”

I do wonder whether panelists on this kind of panel would tend to be more critical than ordinary readers, because:

a) They are listening to the pages read aloud, and I think it is easier to be critical in that format. I feel that I am significantly more critical of books I’m listening to than books I’m reading. I’m not sure that’s true, but I think so. I think the format is slower and anything you dislike — from clunky sentences to implausible fight scenes — stands out more.

b) They are specifically listening in order to be judge the book and be critical. I don’t mean this as a criticism. That mindset is intrinsic to the situation. They are listening in order to stop. They are expecting to stop. The situation is so different than when you pick up a book in a bookstore and read the first page. In that case, you are hoping to enjoy it and aren’t specifically looking for problems.

Despite all the potential caveats, though, I do like the idea of the panel. Even though I would expect a few participants to be thinner-skinned than would be idea.

Incidentally, from Faith Hunter in the comments of Massey’s post:

It would be easier to go the route of self-flagellation than to sit down and read an editorial letter. They are often (usually?) brutal.

That has not been my experience. From what I’ve seen, even editorial letters that ask you to do a ton of work are actually quite nice about it. I suspect that the class on Editoring 101 has a lecture on How To Sound Sincerely Flattering While Pointing Out Serious Flaws. In my experience, even the most perfectionist editors write nonbrutal editorial letters.

November 24, 2015

Recent Reading: Ancillary Mercy by Ann Leckie

So, I finally got a chance to read Ancillary Mercy. Which is to say, I started at the beginning and re-read Ancillary Justice and Ancillary Sword, followed by Ancillary Mercy.

What a fantastic story this is, all the way through.

But you know what? I really do like the second book better than the first. After happening across various other readers’ comments about the first and second books, I thought maybe I was just wrong about my own preference. But, no. I loved the first book. I loved Breq from the beginning, and the worldbuilding, and the setup. But I loved the second book more. And the third, it turns out, about as much as the second. I saw the ultimate solution coming, but for me it’s not about the solution to the problem, it’s about getting to that solution, the details about how the solution is managed, and then the resolution of the story afterward. It’s like a murder mystery: I don’t care much whether I figure out who did it because for me that isn’t the point of reading the mystery. So predicting the solution didn’t interfere with how much I enjoyed the third book of the series.

I do wonder whether a lot of readers predicted the solution, though? It seemed to me that the story *had* to end with essentially that exact solution, that there was no other way out of the corner into which Breq had painted herself.

Anyway, yes, I liked the second and third books best. Partly this has to do with what particular issues Breq is dealing with on the way to defeating the Lord of the Radch, and how she deals with those issues. The situation with the Undergarden, the situation below on the planet, the dire situation with Dlique getting shot, the situation with Spene – all those problems are very appealing, substantially more so than the specific problem in the first book, of how to get at Anaander Mianaai and shoot her, which after all is pretty pointless considering how many of her there are in the Radch. Of course Breq does a lot more than just shoot a couple iterations of Anaander Mianaai; she brings the tyrant’s little problem out into the open and forces her to recognize it. Still, the problems Breq faces in the other two books, and how she handles them, appeal to me more than main problem of the first book.

But I think the main reason I prefer the second and third books is the appeal of the secondary characters. Seivarden is such a jackass in the first book. He improves a great deal over the course of the story and is a pretty decent person in the second book, though he can still be a jerk. But I *really* liked Tisarwat, who didn’t appear till the second book. The dreadful situation Tisarwat endures is particularly appealing to me. Tisarwat is a great character. The reader can just imagine how overwhelming Tisarwat’s experience has been, how difficult it is to deal with. I love how Tisarwat does deal with it and the part she plays in the resolution of the story. Also, I really liked a lot of the almost-nameless supporting cast that appear later in the story, like Kalr Five and Bo Nine. And Station. And Mercy of Kalr and Spene.

And surely everyone loves Presger Translator Dlique and Presger Translator Zeiat? They are so delightfully weird. The thing with eating the oyster was perfect. It was important to demonstrate that the translators are in fact not human, and that does it.

So, as always, for me it’s all about the characters, even more than the worldbuilding. Though the worldbuilding is fabulous. For me, the gender thing is interesting, but fairly trivial. Yes, it implies a more or less gender neutral society, or possibly a society with a tendency toward female dominance. Few if any reviews I’ve read have commented that this gender-neutral or feminized culture is also emphatically repressive, imperialistic, and culturally appropriative – a fabulous juxtaposition of cultural traits that helps the society seem even more peculiar. I appreciated the depth of cultural parochialism shown by the Radchaai and the way that parochialism was supported by their language, in which it’s impossible to say that non-Radchaai are civilized.

But the use of feminine pronouns as the default hardly seems worth all the attention it’s gotten from reviewers. I’m sure you’ve all seen Mark Twain’s essay where he translates a passage from German to English, keeping all the gendered pronouns and nouns intact. “The tomcat, she is carrying her kittens.” Is that so much less strange than the way gender is handled by the Radchaai language? No, what makes gender actually interesting in Leckie’s trilogy is Breq’s unique inability to recognize gender cues, and that’s not a cultural trait of the Radchaai, it’s just Breq. Actually, one could write a human character with that particular disability – it could be seen as a form of face-blindness, a specific deficit in recognizing what you look at. The human brain is peculiar; I can easily imagine someone with such a visual deficit. Wouldn’t that be an interesting thing to do to your protagonist? Though it’s harder to imagine a dysfunction that would extend to recognition of gender by voice.

Anyway, there are lots of more interesting things about Breq than her inability to automatically recognize the gender of people she meets, including her own genderless nature, her memory of having been a ship, her experience of having lots of bodies active at once – Leckie handles this so beautifully – but most particularly, an aspect of her character that I haven’t seen mentioned elsewhere, her complete obliviousness to her own motivations. To me, that is Breq’s single most noteworthy characteristic.

Right there on page one, we see this passage:

Sometimes I don’t know why I do the things I do. Even after all this time it’s still a new thing to me not to know, not to have orders to follow from one moment to the next. So I can’t explain to you why I stopped and with one foot lifted the necked shoulder so I could see the person’s face.

And then Breq rescues Seivarden without the faintest conscious awareness of why she’s doing so, jumps off the bridge to save him without understanding why, and goes right on through the whole trilogy the same way. Oh, she understands some things about herself. She understands that she’s angry, and why – or she understands part of why she’s angry. But there is so much about herself that she honestly doesn’t understand, and that the reader does. For such a long time in the third book, Breq can’t sort out her reactions to Mercy of Kalr, but the reader doesn’t have any trouble understanding what’s going on. And the ultimate solution to the main problem of how to deal with Anaander Mianaai? That only works because Breq legitimately doesn’t see it coming. In a first-person narrative, the way the solution is handled could very easily feel like Leckie hiding the solution from the reader – cheating to make the solution a surprise. But because Breq is unaware of so much of her own subconscious, it does work. Or at least, it did for me.

General rating: Five out of five. Nine out of ten, nine and a half. The actual solution really was predictable, or it’d be a ten.

Best for: Character readers who love ornate worldbuilding and stories set in cultures that are not much like modern American culture.

If you loved the Ancillary trilogy, you might try: The Chanur series by CJ Cherryh. More political, I suppose, but what CJC does with nonhuman protagonists, cultures, and species ought to appeal to readers who loved those aspects of Leckie’s trilogy.

November 23, 2015

The passive voice explained, again

You would think the issue had been settled long since, but no. I blame Struck and White, personally, because they evidently couldn’t tell the difference between the passive voice and the use of “was” or “were” in an active-voice sentence.

Anyway, Katherine Kerr revisits this perennial topic at Book View Cafe, in this case contrasting the passive voice with the progressive tense:

Now consider these:

1. He walked down the road when he saw the bird.

2. He was walking down the road when he saw the bird.

Both are active. The second is in the progressive past tense. … When you are trying to express parallel actions, that is, two things happening at the same time, the progressive tense works much better than the simple past … Sentence 1 is ambiguous, in other words, where Sentence 2 is precise.

Nice example. Click through to read the explanation if you don’t see why the first sentence is ambiguous. Although one might wish to convey ambiguity in motivation, in action, in attitude, or even in outcome, it’s quite true that your job as a writer is to avoid ambiguity in the actual writing.

Mind you, though sentences such as “There were scarlet and orange leaves floating in the pool” are not necessarily passive, constructions using “there were” and “it was” can be problematical for other reasons. (What exactly is the subject?)

However, they are not always awkward.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

This is not passive in construction. And I think we generally agree that the sentence rolls beautifully off the tongue.

And, of course, despite all the scorn heaped upon it, sometimes the passive voice *is* exactly what you want. Remember Admiral Naismith considering the sudden lack of actors from all the action, when his trooper is explaining what happened in the liquor store? I’m not sure if any nongrammarian laughed out loud at that paragraph, but I sure did.