Rachel Neumeier's Blog, page 255

September 15, 2017

The triumph of good over evil in “It”

Here at Terrible Minds, this review of the new remake of IT.

By gum, this makes me want to rush right out and see the movie, even though I am not entirely keen on horror and even though Mike, my favorite character, apparently gets short shrift.

Nevertheless.

Chuck Wendig says:

But I have missed that more mythic, more simplistic story aspect of scrappy band against overwhelming evil. The 1990s saw a greater complexity and a return to the nuance and moral grays of the 1970s — and nothing wrong with that, as those were stories that well-served their times, too, I think. … Now, though, I wonder if my return to more simplistic stories — escapist stories, arguably — has to do with the world around us. This epic shitshow, this constant parade of fear-bugling and rampant fuckwittery. I don’t respond well to Captain America being a Nazi, I respond to him punching a Nazi. I don’t want to play the vampire right now so much as I want to play the vampire hunter. I don’t want to find out that Ellen Ripley has sided with Weyland-Yutani in bringing the Xenomorph to Earth — I want to watch Ellen Ripley jump in a robotic autoloader and fling that Alien Queen out into the void of space. I don’t want every episode of Scooby-Doo to be about how the Gang had to lower themselves morally to the level of Old Man Withers just to win the day. I don’t want them to pull a mask off Shaggy and it’s really the fucking Devil underneath. I sometimes just want them to find the monster, unmask the bad guy, and solve the goddamn mystery, Scoob.

You can see why people are responding well to IT.

If the movie inspires comments like the above, I sure can.

Please Feel Free to Share:

September 14, 2017

Could depression arise from a fundamental problem with prediction?

Here is a long post from Scott Alexander at Slate Star Codex . . . I feel that is a redundant phrase, since as far as I can tell Scott Alexander does not write short posts about anything . . . but though it may be a little tl;dr for some of you, I thought it was very interesting.

You should be aware before going in that Alexander is a psychiatrist and this is a kind of technical post that assumes you have read other recent posts. But I haven’t read those and I’m not a psychiatrist and I found this post understandable and intriguing.

[I]f the brain works to minimize prediction error, isn’t its best strategy to sit in a dark room and do nothing forever? After all, then it can predict its sense-data pretty much perfectly – it’ll always just stay “darkened room” . . . I notice that this whole “sit in a dark room and never leave” thing sounds a lot like what depressed people say they wish they could do (and how the most severe cases of depression actually end up). Might there be a connection?

Alexander is referring here to a theory of how the brain works, called predictive processing, which says, in a nutshell, [Your brain’s] goal is to minimize surprise – to become so good at predicting the world (conditional on the predictions sent by higher [cognitive] levels) that nothing ever surprises them. Surprise prompts a frenzy of activity adjusting the parameters of models – or deploying new models – until the surprise stops.

So Alexander says, applying this to depression, Depression has to be about something more than just beliefs; it has to be something fundamental to the nervous system. And low confidence in neural predictions would do it. Since neural predictions are the basic unit of thought, encoding not just perception but also motivation, reward, and even movement – globally low confidence levels would have devastating effects on a whole host of processes.

It goes on from there, and as I said, this post contains stacked concepts that may lead you off to read about fifty pages of text in order to develop a really coherent idea about what Alexander is talking about. If you find the subject at all interesting, this should prove time well spent. It’s fascinating stuff, and Alexander has a knack for putting abstruse things in pretty understandable terms.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Snowspelled by Stephanie Burgis

Here’s a guest post about Snowspelled over at Mary Robinette Kowal’s blog.

This post is also about the misnamed chronic fatigue syndrome, which as I hope we all know these days has been utterly mishandled by much of the medical profession since that appalling drivel published in Lancet a decade or so ago. You may be aware that Stephanie has suffered from CFS for some time. Here she speaks about that:

It felt like a fairy’s curse descending out of nowhere when I got sick in 2005 and never got better again. I was a healthy 28-year-old who loved to hike and jog and travel, but suddenly my head swam whenever I walked for even half a block. When I spent twenty minutes upright in my kitchen, cooking muffins, I had to collapse afterwards as my teeth chattered with exertion. Worse yet, the doctors couldn’t work out what was wrong with me…so week after week, I had to call in sick to work with no explanation and no prospect of any cure.

I hope that fewer people have such difficulty with diagnosis today.

Anyway, here is the connection:

[L]ike me, Cassandra [the protagonist of Snowspelled] spent her life working towards an ambitious goal – in her case, to change her society’s rules and become the first lady magician in Angland (where ladies, being the more practical sex, are meant to stick to politics while men see to the more emotional and tempestuous magic) – only to find herself derailed in her mid-twenties by a horrible, life-changing incident that takes away her ability to cast magic…and with it, not only her goals and dreams for the future but also her entire definition of herself.

This is an interesting reflection of life through the lens of fantasy, and to me it helps explain why Stephanie so definitely avoided a magic cure for Cassandra’s problem — because in real life, often there are no cures.

I have read Snowspelled, btw, though I haven’t quite got around to finishing a review. It’s quite charming, and the way Cassandra solves her problems without a magical cure for what ails her is in fact one of my favorite details.

Please Feel Free to Share:

September 13, 2017

Ancient cities

Here’s an interesting if short article: What Did Houses For Ordinary People In Sumer Look Like?

The average house was a small one-story structure made of mud-brick. It contained several rooms grouped around a courtyard. People with more resources probably lived in two-story houses, which were plastered and whitewashed and had about ten or even twelve rooms, equipped with wooden doors, although wood was not common in some cities of Sumer….The ground floor in two-story houses, usually consisted of reception room, kitchen, and toilet and servant’s quarters….Most houses (approximately 90 square meters) had a square center room with other rooms built around an area that provided access to the light and ventilated the interior….

Doesn’t this look comfortable and pleasant? Ninety square meters is close to 1000 square feet, which is not that much smaller than my house, so it gives me a fair idea of how much space a family might have enjoyed (at least a wealthier family).

And it’s so interesting what else people substituted for wood. The wealthy used mud brick, but others used reeds:

Sumer had no trees for timber but it had the huge reeds in the marshes, and this raw material was widely used in building of reed houses….People tied reed bundles or plaited them into mats and set vertically in the ground, like columns, in two parallel rows, and then their peaks were tied….“Digging a series of holes in the ground, the builders would insert a tall bundle of reeds in each hole. A circle of holes would be used to make a circular house; two parallel rows to make a rectangular one. Once the bundles were all firmly inserted, the ones opposite each other would be bent over and tied at the top to form a roof. For a front or back door, a reed mat would be draped over an opening (either at the ends of a rectangular house, or on the side of a circular one).

A bit like how the Comanche and other groups constructed tipis, it sounds like.

Slightly related: here’s another archaeological event I happened across recently:

A Lost Underwater City Has Been Found 1,700 Years After a Tsunami Sank It

Archaeologists have come across a vast network of underwater ruins making up the ancient Roman city once known as Neapolis, which was largely washed away by a powerful tsunami around 1,700 years ago….The dramatic deep sea find includes streets, monuments, and around a hundred tanks used to produce garum – a fermented fish sauce that was a popular condiment in ancient Rome and Greece and is likely to have been a significant factor in the Neapolis economy.

There’s a linked video showing the exploration of this underwater site.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Decency in Fiction

Here is a post by James Scott Bell at Kill Zone Blog: The Power of Decency in Fiction

If you’ve been in my workshops or read a few of my writing books, you know about the “pet the dog” beat. The name is not original with me, but comes from the old Hollywood screenwriters. Blake Snyder changed it to “save the cat.” So pet lover-writers can choose their preferred metaphor.

I have refined the concept to make it something more specific than merely doing something nice for someone. In my view, the best pet-the-dog moments are those where the protagonist helps someone weaker or more vulnerable than himself, and by doing so places himself in further jeopardy. Thus, it falls naturally into Act 2, usually on either side of the midpoint.

I think of … Richard Kimble in the movie The Fugitive, saving a little boy’s life in the hospital emergency ward (and having his cover blown as a result).

A “pet the dog” moment! What a great term. Although Kimble risking his cover to intervene and re-write the boy’s medical orders was so much bigger than “petting a dog,” of course. After these recent hurricanes, I think a better phrase would be “rescue the dog” moments.

Lots more about the original Fugitive TV show at the link — I’ve never watched it, but it does sound like something I’d enjoy. Bell concludes:

I say this pet-the-dog motif is the secret of the show’s popularity. … Why do we respond so strongly to this motif? It’s not hard to understand. In this life, which Hobbes described as “nasty, brutish, and short,” we long for decency, thirst for kindness, are grateful for compassion. Seeing it manifested in a lead character draws us to him, creates the bond that is one of the big secrets of successful fiction.

I agree, except that I think the desire to be kind can be and should be at least as important as the desire to have other people be kind to us.

I’m currently reading the Danny North series by Orson Scott Card, which is an interesting story to look at in this connection. Twice now one or another supporting character has referred to or thought about Danny as a particularly good person, and this seems to be important in various ways. But . . . I’m not really seeing it. I think there are not enough overt “pet the dog” moments to make up for what appears to be quite ordinary non-goodness. The books are kind of fun and intellectually engaging, but I can’t say that Danny is a very appealing protagonist. Nor are any of the secondary characters particularly appealing. This is a personal assessment, of course; your mileage may vary. Still.

Comparing Danny North to, say, Cassandra or Kaoren Ruel of The Touchstone Trilogy … there’s really just no comparison in terms of moral character. They’re hardly even in the same moral universe. And I’m with Bell: I think that matters A LOT when it comes to readership appeal and successfully deepening the emotional involvement of (many) readers. For me, the Danny North books will be a read-and-give-away series, whereas you could not pry the Touchstone series out of my fingers with a crowbar.

Please Feel Free to Share:

September 12, 2017

Not feeling like you have an adequate grasp on the emotional possibilities of humanity?

Here is a post from Berkley: Scientists pinpoint 27 states of emotion

A new UC Berkeley study challenges a long-held assumption in psychology that most human emotions fall within the universal categories of happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, fear and disgust….“We found that 27 distinct dimensions, not six, were necessary to account for the way hundreds of people reliably reported feeling in response to each video,” said study senior author Dacher Keltner, a UC Berkeley psychology professor and expert on the science of emotions.

Moreover, in contrast to the notion that each emotional state is an island, the study found that “there are smooth gradients of emotion between, say, awe and peacefulness, horror and sadness, and amusement and adoration,” Keltner said.

I must admit that I am not super-impressed by this “new” delineation of “newly recognized” emotional states. The reasons we have different words for aesthetic appreciation, awe, admiration, joy, and adoration, among so many others, is because we already recognize these concepts as expressing distinct emotional states.

This link is via The Passive Voice, where TPG says, “PG says this may permit authors to break away from old emotions for their characters and use brand new emotions. Or not. Authors have managed to do quite a bit with happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, fear and disgust without (in PG’s emotionally humble opinion) exhausting all the possibilities.”

Yes, no kidding.

Significantly more interesting imo is this 2013 article: 21 Emotions For Which There Are No English Words, which gives us, for example:

Litost (Czech): a state of torment created by the sudden sight of one’s own misery

Pena ajena (Mexican Spanish): The embarrassment you feel watching someone else’s humiliation

Gezelligheid (Dutch): The comfort and coziness of being at home.

Also, five “new emotions” connected to the computer age. I note in passing that all of these are negative.

Please Feel Free to Share:

September 11, 2017

Sixteen years ago

Remembering 9-11-01

This September:

Harvey

Irma

Wildfires

It’s hard to know what to say. Except:

Eight inspiring acts of heroism and kindness from Hurricane Harvey

Viral photos show heroic police response to Hurricane Irma

Heroic firefighters saved her home, survivor says

and also

7 incredible stories of heroism on 9/11

Please Feel Free to Share:

September 8, 2017

The worst movie ever made: terrible movies face off

Via File 770:

Announcing: The Worst Movie Golden Bracket

The Golden Turkey Awards. The Golden Raspberry Award. Awards given to the worst of the worst movies. So this will be The Worst Movie Golden Bracket.

This is about chosing the worst movie ever made. A bad movie is not a boring movie. It is a movie that creates feelings. Astonishment that the movie could ever be made. Fascination over who could create it. Anger over those who participated in it. Enthusiasm over the brilliance needed to make something so bad.

Provided for perusal: an alphabetical list of terrible, terrible movies.

I have of course not seen all that many of these. I have to agree about Highlander 2. That was an awful, awful movie.

Click through and enjoy! If you have your own candidate that’s not yet present, you can nominate it.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The tradition of epic fantasy

Here is a long post by Paul Weimer at Supernatural Underground, about the way epic fantasy has changed as a subgenre.

The First Era of Epic Fantasy

The pre-geologic era, our first era, is the period before there was a defined class of literature called epic fantasy. That is to say that there was no defined subgenre of fantasy and science fiction that one could point to, or ask for, that was called epic fantasy. A time traveler to that era, going to the bookstore or a library or even a SF convention would just confuse people by asking for “epic fantasy.

Paul delineates four eras following the period referenced above, in which the foundation for epic fantasy was laid by Tolkien and a few others. Then:

The First Era — Stephen Donaldson and Terry Brooks

The Second Era — D & D; also many female authors; also the period when the SFF scales started to lean toward fantasy rather than SF.

The Third Era — The Grimdark era, in which Paul references Kate Elliot’s King’s Dragon series, thus instantly making me shuffle that downward in my TBR pile, so I would like to know: those of you who have read that series, do you agree that it is grimdark? I don’t agree that grimdark is characterized primarily by moral ambiguity; as far as I’m concerned it is defined by the world and more than likely the protagonists being worse off at the end than they were at the beginning.

The Fourth Era — Paul says:

…the Cenozoic of my epic fantasy geologic timeline – the era we are currently in – is the era in which The Wall of Night series is a leading light….The basic epic fantasy chassis developed over the previous eras is here: A young protagonist, a woman, the heir to power, but with real doubts and real growing up to do. A quest to stop a previously thought-to-be-contained evil from overwhelming the world – and the “thin red line” of the people known as the Derai. A complicated, complex and richly drawn fantasy world that rewards a deep dive….And with all that, Lowe brings forward the concerns and richness of this new era…reaching out beyond The Great Wall of Europe for ideas and models for cultures, characters and worlds.

The Wall of Night is another one that’s on my TBR list. This kind of description moves it up toward the top. Again, comment, please, if you’ve read it. What did you think?

The whole post is well worth a look, if you’ve got a moment.

Please Feel Free to Share:

September 7, 2017

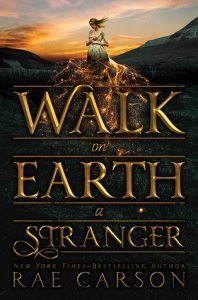

Recent Reading: Walk on Earth a Stranger by Rae Carson

Okay, so, I know, Walk on Earth a Stranger has been out for a few years. And it’s actually been on my radar the whole time. But what gave me a shove recently was seeing a tweet about it being a Kindle special for $1.99. I’ve ignored my share of notifications about Kindle deals, but by a startling coincidence I was at that moment exactly in the mood for a detailed, well-researched historical novel, with or without minor fantasy elements, which I knew described this novel. So I guess it was meant to be.

I read the first book, then immediately bought the second, Like a River Glorious, and read that one too, then preordered the third, Into the Bright Unknown, which is due out next month. I expect that’s why the first suddenly went on sale, which is certainly an excellent strategy; you see how it worked for me.

So, the Gold Seer trilogy. I loved it. Let me see, where to start . . .

Okay, the first thing to know about this trilogy is that it is very much a historical, with only a minor snippet of magic in the first book – the main character, Leah Westfall, is a gold dowser. Which is super handy since this story is set during the era of the California Gold Rush. But this fantasy element is VERY minor in the first book. Leah’s gift develops a bit more in the second installment and one can definitely anticipate an even larger role in the third. As far as I can tell, there are precisely zero other magical elements in the trilogy, though there are hints here and there that Leah’s gift may not have come completely out of nowhere.

The historical setting is the point, though, not the magic. Tell me, how did you feel about Tolkien covering every. single. day during TLotR? Did you get bored by that, or did you enjoy traveling along every step of the way with the characters?

I inquire because – I’m sure you can see this coming – Carson’s book is very much a day-to-day travel narrative. From time to time we leap lightly over a few days or weeks, but virtually the entire book is taken up by Leah’s journey from Georgia to California, and let me tell you, there’s nothing like reading about the wagon trains to make the reader appreciate modern life. Dust, mud, rivers, desert – ugh, that desert! – mountains, heaps of scenery everywhere you look, not to mention loads of people with gold fever heading west with their children, their livestock, and occasionally their dining room furniture.

I was exactly in the mood for this story, as I say, but – without checking reviews – I would bet there are some readers who were all, Wow, this is sooooo slow. Not that things don’t happen, but still, that is one looooong journey.

The second thing to know about the trilogy: Leah – mostly called Lee – is a great protagonist, surrounded by great secondary characters. Mrs. Joyner is my favorite of the secondary characters. She develops and changes a great deal over the course of the first book, in a way that reminds me of Barbara Hambly a bit. She starts off kind of . . . well, thoroughly . . . unsympathetic. I started rooting for her about two-thirds of the way through and was definitely cheering her on by the end.

Another element of secondary character development I particularly appreciated is how so many of the minor characters have their own stories, to which Leah herself is tangential. They come into, and more importantly depart from, the narrative in a way that is unusual for a novel but seems very true-to-life of how people would have come together and then separated during the westward trek across the continent.

I will just add that the trek is grueling, that there’s not much law in force for most of the distance or in California, and that sometimes people die. Carson doesn’t linger on these scenes, but . . . yeah, this was a brutal period of history in a lot of ways. From time to time Carson does soften some aspect of the journey a little – I mean, this is before the germ theory of disease, but the guy who was training to be a doctor is surprisingly up on the importance of cleanliness. Which probably some people who practiced medicine were, but really, the 1840s were still solidly within the Dark Ages of medicine, the era during which often going to a doctor lessened rather than improved your chances for survival. Still, Carson makes her presentation of 1840s medicine believable.

Which kind of leads into the third thing you should know about this trilogy, thus: although Carson does soften the edges of the era by handing Leah and many of the secondary characters more modern opinions and attitudes in order to make them sympathetic to modern readers, she also handles social issues subtly enough that these attitudes seem neither jarring nor preachy. That’s a feat otherwise excellent writers sometimes fail to pull off. Leah and Jefferson and several others despise slavery, but in these decades leading up to the Civil War, lots of people did feel exactly that way, so that’s believable. Similarly, Leah rejects the common view of Indians, but given Jefferson’s background, this is totally natural. Leah also furiously rejects the way society treats women as chattels, but given her immediate backstory this would definitely be something she’s questioned and come to fear and hate. All those modern mores are completely integrated into the character backstories and make sense in story terms.

Nor does Leah depend on having modern attitudes to render her sympathetic to the reader. Her defining characteristic isn’t a modern sensibility, it’s – in my opinion – a very old-fashioned sense of charity. She works hard not to resent Mrs. Joyner’s initial rejection, instead striving to see the situation from the older woman’s point of view. Later she works hard not to hate Reverend Lowry for what happens to his wife, but to be sympathetic to his point of view and his genuine grief. People have to be pretty bad – bad clear through, really – for Leah to totally reject and loathe them.

Leah’s certainly brave and generous and attached to her horse, but those are attributes we expect of any YA type of heroine today, right? Sometimes she gets angry and sometimes she gets confused and all that is pretty typical as well, and certainly sufficient for her to work as a protagonist. But the more I think about it, the more I think it is her sympathy and her concentrated attempts to view everything, with charity, from the other’s point of view, that sets her apart. Actually, this is something of an antidote to the more common modern attitude, where all too often it seems that we see people strive to vociferously reject any point of view that differs from their own in the smallest detail rather than work for understanding. Leah’s sympathy for the points of view of others fits beautifully with the historical period, as it does seem like a virtue of that period.

Overall, two excellent installments in a vividly realized historical period. I’m glad the third is coming so soon – I know I’ll dive right in the moment it pings into my Kindle.

Please Feel Free to Share: