Rachel Neumeier's Blog, page 184

November 14, 2019

Dark fantasy versus gritty fantasy.

Recently I said that dark fantasy is not the same thing as gritty or grimdark fantasy. Let me go on with that now, with an attempt to pull apart dark fantasy from gritty fantasy. I feel this is a useful distinction because if you just search for “dark fantasy,” a whoooolllle lot of the suggestions are either very gritty or grimdark, but are not by any stretch what I would prefer to call “dark fantasy.”

I said the other day that dark fantasy should have the following characteristics: It should have a high fantasy or mythopoeic tone, it should be atmospheric, the fantasy elements should remain largely or entirely unexplained, and the protagonist(s) should be heroic rather than helpless or ineffectual.

This is, of course, a personal type of definition. But if we follow it for a minute, then obviously gritty fantasy is completely different from dark fantasy. I like a certain amount of grit in fantasy — sometimes — if it’s well done, not overdone, and I’m in the mood — but gritty fantasy has almost nothing in common with horror and therefore is not very similar to dark fantasy either.

Let’s take a close look at gritty fantasy.

Gritty fantasy, in my opinion — and I think this fits everyone’s opinion — specifically does not have a high fantasy or mythopoeic tone. The worldbuilding instead emphasizes some or all of the following features of daily life: extreme poverty, filth, prevailing ignorance, selfishness, the misery and general ugliness of daily life. In gritty fantasy, streets are filthy, and we get a good look at the sewage. Beggars might have rotting fingers, and we get to smell the putrification. Poor families might sell a child to slavers, and they might not feel especially bad about the necessity, either.

All of these attributes were indeed typical of many (most) human societies, but I don’t personally want to read about a world where these features are brought front and center, even if the protagonists appeal to me and the writing is good and all of that. Some grittiness can be fine as long as the author also shows us the beauty in the world. The grittiness then becomes an additional layer added to the world, a layer that is more or less elided in high fantasy. I’m not always too keen on that layer, but it depends on the extent of the grittiness.

Here are some examples of gritty fantasy, lined up in descending order of grittiness:

Unendurably gritty: Dark Apostle series by EC Ambrose.

I tried to read this book. I like the idea of a surgeon in a fantasy novel; I’m fine with the historical surgeon-barber profession. Here is part of the back cover description of this book:

Elisha Barber is good at his work, but skill alone cannot protect him. In a single catastrophic day, Elisha’s attempt to deliver his brother’s child leaves his family ruined, and Elisha himself accused of murder. Then a haughty physician offers him a way out: serve as a battle surgeon in an unjust war.

The novel opens with that “single catastrophic day.” Not only is the day catastrophic, the setting also brings every gritty worldbuilding element into the forefront and dumps it all, like a bucket of rotting offal, over the reader’s head. I didn’t make it to the offer from the haughty physician.

Moving on to tolerable levels of grittiness:

Gritty: Scott Lynch’s Gentleman Bastards series; the Night Angel serieby Brent Weeks. I read these and like them, but I have not gone back to re-read them. The one by Weeks, I gave away.

Somewhat gritty: Django Wexler’s Shadow Campaigns series. Now we’re at a level I can appreciate. I love this series and highly recommend it to anyone as an example of outstanding epic fantasy.

A bit gritty: Tamora Pierce’s Beka Cooper series. Yes, really. This series is very different from Pierce’s middlegrade series. It’s much more sophisticated, much “bigger,” and much grittier — without being too much for (most of) Pierce’s young readers. But the focus on the street-level grime, poverty, crime, and daily life place this series firmly in the gritty category as opposed to the high fantasy side of the genre.

In this case, this is by far my favorite of Tamora Pierce’s series. Long and slow-paced at times, but I’ve re-read the whole thing a couple of times and will undoubtedly do so again in the future.

This all boils down to the essential difference between high fantasy and low fantasy, except it’s between a specific type of high fantasy (dark) and a specific type of low fantasy (gritty). I think this is actually a quite useful distinction, much more so than just lumping together everything with unpleasant or scary or grim aspects and calling it “dark fantasy.”

If you have a suggestion for a gritty fantasy — but not too gritty — drop it in the comments! Or if you’d like to redraw the lines of the definitions, then by all means, jump in and lay out where the lines should be between horror, dark, and gritty.

Next week sometime, I’ll try to separate grimdark from gritty. Fantasy can absolutely be extremely gritty, far too much so for my personal taste, without being grimdark.

Please Feel Free to Share:

November 13, 2019

Viking warrior woman

Scientists Reconstruct The Mutilated Face Of A 1,000-Year-Old Female Viking Warrior

A skeleton found in a Viking graveyard in Solør, Norway has been identified as female for years, but experts weren’t sure if the woman was really a warrior when she was alive. Now, cutting-edge facial reconstruction appears to confirm her status as a fighter.

According to The Guardian, archaeologist Ella Al-Shamahi explained that this latter part was in dispute “simply because the occupant was a woman” — despite her burial site being filled with an arsenal of weaponry that included arrows, a sword, a shield, a spear, and an axe.

This does seem somewhat odd to me. What can a facial injury tell you that burial with an arsenal can’t? It seems to me like the number of nonfighter women murdered with swords and spears must be quite a lot higher, to put it mildly than the number of warrior women killed in battle. Nothing in the article suggests why a specific wound indicates death in battle rather than slaughter of a noncombatant. Personally, I think the arsenal is a lot more suggestive than the wound.

However, it’s always something to see the face of someone out of history.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Where did the Berlin Wall go?

I happened across this post just now: The Berlin Wall Fell 30 Years Ago. Where Did It Go?

The wall spanned 96 miles, encircling West Berlin. It stood for nearly three decades until November 9, 1989, when East Germany suddenly opened its borders and crowds began tearing it down.

In the 30 years since, chunks of the wall have made their way to some 237 locations in more than 40 countries, according to records from a German government foundation tracking them.

I can tell you, chunks of the wall have made their way to a lot more than 237 places. I have a piece myself, picked up in person by my brother, who was in Germany at the time.

Nice event to commemorate. Definitely a good one to remember; I’m glad to have noticed various articles and posts about it. Hard to believe it’s been thirty years.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Dark Fantasy vs Horror

So, I commented last week that T Kingfisher’s The Twisted Ones is perhaps more dark fantasy than horror. I think this is the case. But then why would I, or anyone, say this? What is the difference?

There is one fairly obvious differences, like so:

Horror does not have to have fantasy elements. It can draw solely on the horror internal to the human condition — Misery, by Stephen King, for example. Or it can use real-world elements and nothing but — Cujo, for example. Or it can use science-fiction-y elements, such as genetic experimentation gone awry or computers that develop in odd ways or, of course, aliens.

Dark fantasy must by definition use fantasy elements.

But okay, plenty of horror does include fantasy elements or supernatural elements, so how do you separate horror fantasy from dark fantasy? Blood and body count? This post at Disquieting Visions argues that if the adventure is foremost, it’s dark fantasy, while if generating suspense is foremost, it’s horror. That post suggests that the distinction is made, essentially, by whether the reader of the book would tend to exclaim: “You got blood on my adventure!” vs. “Your adventure is detracting from my sense of pervasive fear!” That is a very nice line. This definition would perhaps make The Twisted Ones horror, at least at first, although the second half might be dark fantasy.

However, I don’t agree that this is necessarily the case. It seems to me that there is a whole lot of adventure in a good many horror novels, superseding the atmosphere of dread; for example, in It. Though again you might then say that most of It is horror, but the last part is dark fantasy. But since It is a horror classic, that suggests the definition needs work. You really cannot use a definition of horror that excludes half of all classic horror works.

Here’s another post that I liked quite a bit: On Dark Fantasy, by an author named Lucy Snyder.

Horror is about an intrusion of the frightening and unknown into a mundane, everyday world the reader is familiar with. … The intrusion doesn’t have to be supernatural (a deranged serial killer will do just fine) though it often is.

Dark fantasies have an established setting that is fantastic or otherworldly. … If you start out in a world where vampires or ghosts or magic are treated as a “normal” occurance by the characters, it’s a fantasy world.

So for Snyder, horror is not about suspense or blood; it’s about the intrusion of the frightening into the mundane world. I could go with that, and in that case, again, The Twisted Ones would fall into the horror genre — again, tending a bit more toward dark fantasy toward the end. However, there are so many fantasy, not horror, novels where something fairly creepy intrudes into the mundane. Bone Gap by Laura Ruby. Shadows, by McKinley. Just a huge number. So I’m just not sure I’m happy with that definition either.

Snyder makes two more important points, but I’m not sure either works much better for me than the first. One is that the protagonists of dark fantasy novels are heroes, who at some point deliberately choose to face something terrible in order to save others; while the protagonists of horror novels are victims, forced to face something terrible because they can’t get away. This is very much, I think, like the adventure versus pervasive dread argument above. Heroes choose to act and therefore their stories are adventures. Victims of horror aren’t choosing anything and just want to survive.

Well, you know, this still doesn’t work. A whooooole bunch of horror novels have heroes, including classic novels like, again, It, and also The Stand and just about everything by Dean Koontz. You can either define all those as dark fantasy — even if they also involve the intrusion of eerie elements into the mundane world — despite the obvious fact that they are considered absolute classics of horror. Or you can give up on this characteristic.

I will add, though, that this particular element is a big driver of whether a dark fantasy / horror novel will work for me. I very much prefer heroes. I am not into helpless victims, even if they eventually take action to save themselves. I loathed Misery almost as much as I hated Cujo. In the latter, I was so filled with contempt for the ineffectual protagonist that I came close to throwing the book in the trash rather than giving it away. These days I would never bother finishing a story like that one.

But moving on: The other point Snyder makes is this: In many dark fantasies, there’s an implied promise that the characters the reader cares about will make it out alive in the end, and the day will be saved, while in horror neither is guaranteed.

I suppose this might have been true at one time, but the rise of grimdark fantasy zaps the distinction completely. Grimdark fantasy is not horror, but there is no such implied promise. Also, I always considered Dean Koontz to be writing “horror lite” — that is, horror where the good guys are going to live and the day will be saved. But those are still horror novels; nobody would call them dark fantasy, just as no one would peg Joe Abercrombe grimdark classic The Blade Itself as horror. This could be a matter of historical convention: if an author started writing when horror was popular, he’s writing horror. If his career took off when horror was in eclipse, we find another word for what he’s writing — grimdark or dark fantasy. Which, by the way, I think of as completely different subgenres.

When I picked up The Twisted Ones, I did indeed assume the good guys would win and the day would be saved, based on T Kingfisher’s other work, and if I’d been wrong I’d have been pretty unhappy about that. Since it’s marketed as horror, should I have been worried? I don’t think so. Lots of authors write horror where you can be pretty sure the good guys will triumph, at least the good guys you most want to survive.

Anyway, all this leaves the question of what, if anything, distinguishes dark fantasy from horror still unresolved. So far we have:

a) Horror involves intrusion of the weird and scary into the mundane world; dark fantasy involves secondary worlds and/or fantasy elements.

b) Horror involves the maintenance of pervasive dread rather than adventure; dark fantasy prioritizes adventure above the maintenance of pervasive dread.

c) Horror involves victims who have little other goal than survival; dark fantasy involves heroes who strive to save not only themselves but others.

d) Horror means no assurance about any characters surviving; dark fantasy carries an implicit promise that all or most of the characters will survive and the adversary will be defeated.

None of these defining characteristics seem to me to do a very good job of separating dark fantasy from horror. What else might work better to actually distinguish the two? Any ideas? Or should we just give up and declare there is no difference other than a marketing decision? Or should we say, “I don’t know, but I know it when I see it?”

Here’s where I would start:

a) Tone. Dark fantasy should be eerie and atmospheric. The feel should be high fantasy or mythopoeic. Grotesque is fine, but not buckets of gore splashed all over everything. It should not be overly gritty. It should not intergrade with grimdark. That is a different sub-subgenre.

b) The eeriness should be unexplained. Aliens, no matter how strange, are not eerie. Pseudoscience need not apply. Definitely no computers gone amok.

c) There should indeed be heroes rather than solely victims, and most or all of the characters should survive. If someone dies, it’s because they deliberately sacrifice themselves, not because the author threw in gratuitous death for no particular reason.

d) It is not primarily a romance story. Paranormal romance is a different subgenre with an entirely different “feel” to it. some Urban Fantasy might also be dark fantasy, however.

Here are some examples of what I would consider actual dark fantasy, in basically no order except how I thought of them:

1)Uprooted by Naomi Novik

2)Cuckoo’s Song by Francis Hardinge

3) Coraline by Neil Gaiman

4) Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children

5) The Dark Tower series by Steven King

There, that’s five, enough to go on with. I’ll add one more:

6) The City in the Lake

What do you all think? What constitutes dark fantasy, and what novel do you think is a good example of the subgenre?

Please Feel Free to Share:

November 7, 2019

Novels based on folk legends

At tor.com, this post by Shea Ernshaw: 5 Fictional Books Based on Real Folklore

We’ve all heard them: local legends and small-town rumors, whispers of an eerie abandoned house, a spooky bridge over a dried riverbed, a haunted forest. … The following YA books were inspired by real world myths and legends and unexplained tales—my favorite kinds of stories.

This seems topical, considering I just posted about The Twisted Ones by T Kingfisher. That story concerns “holler people;” that is, stranger inhuman people who are associated with certain hollers.

Hollers, as you probably know, are an Appalachian term for “hollows,” meaning little valleys among the mountains. The Twisted Ones is set, I think, in North Carolina, so Appalachian or at least Appalachian-adjacent. I don’t know whether T Kingfisher drew on any specific Appalachian or local folk legends for the story … wait, I don’t think so, she says in an author’s note that she drew on a specific literary inspiration: Arthur Machen’s 1904 short story, The White People.

However, it feels like it’s based on a folk legend, so that’s good enough.

All the books featured on the tor.com post look like dark fantasy / horror. I’m just judging on title here, but “Teeth in the Mist” sounds like horror. So does “The Devouring Gray.” This one sounds interesting, in a way:

Conversion by Katherine Howe

Inspired by true events, Conversion is the story of several friends attending St. Joan’s Academy who are inexplicably struck by a strange condition which causes the girls to suffer from uncontrollable tics, seizures, hair loss, and coughing fits. … this book was based on the real-life events that took place in a high school in Le Roy, N.Y. where high school students began suffering from similar ailments. The community of Le Roy feared it might be pollution or poisoning of some kind, but it was eventually determined to be a case of “conversion,” a disorder where a person is under so much stress that their body converts it into physical symptoms. Also known as hysteria.

I’m skeptical about that conclusion, so here’s a link to a Skeptical Inquirer post about that if you’re interested. However, judging from the couple of posts I glanced over, it does appear that this might have been a case of mass hysteria.

However, I don’t want to move on from this topic without pointing out that, of course, the single best example of Appalachian folklore-based fantasy must surely be the Silver John stories by Manly Wade Wellman. I’ve been re-reading those recently and I’d forgotten the extraordinary colloquial style. If you’ve never read any of the Silver John stories, some of them are available online here.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Recent reading: The Twisted Ones by T Kingfisher

Okay, so, it’s not like I’ve read through the

entire backlist available for T Kingfisher / Ursula Vernon. I’ve got several of

hers on my TBR pile and a vague notion she’s got a lot of others out there. But

I’ve really enjoyed all of her books or stories that I’ve read so far, so when

I noticed The Twisted Ones, I was interested and also ready to trust her

to write a horror story I could stand to read. I was in the mood for horror

because hey, Halloween. I didn’t actually read this book in time for Halloween,

but I think I might have ordered it on Halloween, so that counts, right?

So, The Twisted Ones.

When Mouse’s dad asks her to clean out her dead grandmother’s house, she says yes. After all, how bad could it be?

Answer: pretty bad. Grandma was a hoarder, and her house is stuffed with useless rubbish. That would be horrific enough, but there’s more—Mouse stumbles across her step-grandfather’s journal, which at first seems to be filled with nonsensical rants…until Mouse encounters some of the terrifying things he described for herself.

What I expected:

Good characterization. I didn’t expect a first-person narrative, but that’s what this story offers, and with a distinctive, engaging voice, too. Mouse is a freelance editor, by the way. On the second page she describes her job this way: “I turn decent books into decently readable books and hopeless books into hopeless books with better grammar.” I did laugh, yes.

This is a contemporary setting – apart from

the dark fantasy / horror aspects — and Mouse sounds just right for a

contemporary protagonist, but she is definitely not a cookie-cutter Modernday

Plucky Female Protagonist or anything like that. She’s herself. I easily

believed in her.

What I didn’t expect:

The dog. I don’t know why I didn’t expect the dog to be this important because I did see a review that assured me the dog didn’t die, but I thought the dog would be a minor character. Nope. He is quite central all the way through. When Ursula Vernon refers to her Hound on Twitter, I guess it’s a literal hound; that is, a scenthound and not “hound” being used as a generic term for “dog.” She sure knows hounds, and she brings this one to life.

In The Twisted Ones, Bongo is a redbone coonhound, and his name bothered me a bit because I know what color Bongo antelope are, but I also know what shape they are, and I kept feeling like a dog named Bongo might have a terribly roached back.

This is a bongo antelope. This is not the way a dog’s back should look.

If a dog’s roached back is extreme enough to remind you at all of a bongo’s back, that would be a dire fault with serious fitness consequences. I had to specifically stop myself at first and visualize a correctly structured redbone coonhound every time I saw his name. Like this one:

This is a really nice coonhound from Grand River Redbones. A grand champion, many other titles. I’m linking their site because I hope they don’t mind I borrowed their picture to illustrate this post. Now you have an image for the dog in The Twisted Ones, though that was an older male and this is a younger female.

Anyway, I did get used to the name eventually, but as a personal request, if any of you ever name a fictional dog, please do not name him after an antelope with seriously undoglike conformation. For example, “Klipspringer” would be a bad name in exactly the same way that “Bongo” is a bad name, plus of course a bit too long to spit out in a hurry if you are frantically calling for your dog to come back when he has jerked the leash out of your hand.

Well, yes, that was a digression.

So, despite his name, Bongo is a fantastic character and the relationship between him and Mouse is actually by far the most important relationship in the story, so if you are keeping an eye out for a book that doesn’t have even a trace of romance, here you go. Naturally I found this a highly appealing focus for a story. Also, if I hadn’t known the dog lived through the story, I might not have been able to tolerate the part where he gets lost in monster-haunted woods. I mean, this is actually a literal nightmare for me. Not the monster-haunted part, obviously, but the lost in the woods part. The fear of a dog getting out and lost is both a (fortunately occasional) nightmare and a source of a constant low-grade paranoia during my waking hours. Losing a dog is about the worst thing ever, as far as I’m concerned – and as far as Mouse is concerned, too. Why do you stay in a terrible house surrounded by monster-haunted woods? Well, because your dog is out there in the woods and he might come back, so obviously you can’t leave.

What I expected:

Clever plotting.

What I didn’t expect:

Such great reasons for the protagonist not to

run away like a bunny, the way any sensible person obviously would. At first

Mouse doesn’t run away because her dog is so blasé about the house and not

nervous about the woods and just does not seem weirded out (most of the time).

I loved this. The oh-so-sensitive psychic dog is kind of a cliché. Bongo is not

one bit like that. Eerie supernatural things have to really whap him upside the

head before he notices them.

Then, when things get scary, Mouse would very

much love to run away like a very fast bunny, but she can’t, because Bongo is

lost in the woods. And then there’s another great reason for her to stay even

after he reappears. T Kingfisher makes those decisions almost believable,

though I don’t know about that last part, I might have said – probably would

have said – the hell with this, my dog and I are outa here.

What I expected:

A gothic-ish horror novel with good

atmosphere, without too much death and gore, and with the good guys coming out

all right at the end of some clever plotting. This just seemed pretty likely

given the other books I’ve read by T Kingfisher / Ursula Vernon.

What I didn’t expect:

This is really more dark fantasy than horror.

There’s this neat creepy passage, central to the story and often repeated, which I will now share with you:

I made faces like the faces on the rocks,

and I twisted myself about like the twisted ones, and I lay down flat on the

ground like the dead ones.

There, that is genuinely creepy, especially

the way it gets into Mouse’s mind. I like poems and stuff in fantasy novels and

this may not be a poem, but it is the same basic idea. It was used very

effectively to provide an eerie feel to a setting that seems mostly normal at

first.

The plotting is indeed pretty clever. No

surprises there.

What carries the book:

Mouse, Bongo, and a handful of well-drawn secondary characters. Very nice writing. A brisk pace that neither lags nor rushes. Tension, but not tension that is wound up so tight you can’t stand it. Knowing from the start that the protagonist and her dog are all right at the end reduces the tension to just about the ideal level as far as I’m concerned. I don’t like horror that is too horrific. This isn’t. As I said, it’s perhaps more dark fantasy than horror.

Who should read this book:

If you like a creepy, atmospheric,

faerie-adjacent dark fantasy/horror story that isn’t very gory or too

incredibly grim and doesn’t have a high body count, then here you go. If you

also like dogs, especially scenthounds, then this is definitely a

must-read. Anybody who loves Robin McKinley’s books, most particularly anyone

who liked her Shadows, should absolutely read this book. The Twisted

Ones also did remind me of Sunshine, but this is a smaller, more

intimate story. The world beyond the immediate setting is basically ordinary

and unimportant; the cast is smaller, with fewer important secondary

characters; there is no broad slow-motion war between Evil Supernatural

Creatures and the rest of us; none of that. But the style is not dissimilar,

Mouse has very much the feel of one of McKinley’s protagonists, and of course

there is the dog.

I haven’t been keeping track of the books

I’ve read this year – a ton of re-reads and relatively few new-to-me books –

but if I had, this would wind up near the top. Highly recommended.

Please Feel Free to Share:

November 6, 2019

Effective first lines — for query letters

Janet Reid just posted a whooooole bunch of first lines of queries, with a note about which ones worked and comments about how they failed. Note that these are first sentences of queries, not novels. Have that in your mind and click through — these are pretty neat to read. I would probably have written my queries differently if this blog had been available at the time, though I have to say, I don’t really remember exactly how I did write them.

Anyway —

Most interesting failure mode: The querier presented a logline — a summary of the story or at least of the initial setup of the novel — as the first sentence. Those are so hard to write! Many were quite good, including this one:

Richelle Elberg

A pile of dead coyotes rotting in the desert is shocking, but it’s the discovery of two bloated human bodies–hidden amidst the carnage–that really gives Detective Em Thayer a jolt.

That’s a fine one-sentence summary to set up a detective novel, don’t you think? I don’t think the dashes are necessary, and I say that as a card-carrying member of the dashes-are-great club. But if I saw this description of a detective novel, I would read the rest of the back cover and the first page.

At least for Janet, however, that is not the best kind of first sentence when writing a query letter to an agent. She wants to see the character and the problem in the first sentence.

Some of these are indeed very enticing. For example:

Kate

In twelve months, the supercomputer grafted to eighteen-year-old Sil Sarrah’s brain will kill her.

and

Jenn Griffin

Batty Betty finds an abandoned young boy in her woods and takes him home–for keeps.

and

Luralee

Being on display in a spiked iron cage on the hottest day of the year is painful and humiliating, but not as serious as his other problem.

I would absolutely use the character’s NAME in this sentence. Almost never works to reserve the character’s name, imo. But other than that, I really like this! Would could possibly resist reading the rest of the query?

Here’s another:

E.M. Goldsmith

Phaedra damned herself by chasing her murderer straight into Hell.

Good heavens, yes, that is a great opening for a query! Also a great description of the set up. This would make a great tagline to put on the front cover of the book.

Kate Higgins

This time she was absolutely, positively going to win, this time she was going to cheat the right way.

Even better! Despite the comma splice, I love this. It’s hard to pick a favorite, but I think this is mine.

Please Feel Free to Share:

Showing rape in SFF

Here’s a good post from Marie Brennan at Swan Tower: Thoughts on the Depiction of Rape in Fiction

Brennan has an archive of good essays at her website, many about the craft of writing. This one demonstrates that. Here’s a sample from near the beginning:

There are a lot of reasons you might have one of your characters be raped. Some of them are better than others; all of them are things you should think about.

1. I need to show that my villain is evil.

. . . okay. But why rape? Why is that your go-to method for showing he’s evil?

It’s one thing if you’re writing a mystery about a detective hunting down a serial rapist. In a story like that, the bad guy raping people is the entire point. But if your villain is a genocidal tyrant? Then I kind of give the side-eye to the notion that you need rape to convince me he’s bad. If that’s true, you haven’t done a very good job writing the “genocidal tyrant” part.

This is a serious topic, obviously, but I did chuckle at the last sentence of the excerpt above. That’s definitely true.

The broad category of “worst things I’ve seen in fantasy novels” doesn’t include many instances of rape — I know other readers say their experience differs in that regard, but I think the books I’m reading must not overlap much with the ones they’re reading.

The “worst things” category does include Gedder, in Daniel Abraham’s The Dagger and the Coin, who burns down a city after blocking the gates so that no one can get out. There is a genocidal tyrant, even though Gedder is not really a tyrant, at least not at the time, as he doesn’t have that much power.

Enough to burn down a city with the population locked inside, though.

It is not necessary to show Gedder doing anything cruel, in person, to an individual. In fact, showing him being cruel on an individual level would make him less awful. A villain who glories in being vicious is probably not as utterly horrifying as a villain who sort of stumbles weakly into mass murder, then justifies the act afterward.

Ugh.

This moment, and this character, are not the only reason I never went on to the second book in that series. But they contributed to that reluctance.

A good example of epic fantasy with a gritty edge and many villains, some quite complex and some simpler, is The Shadow Campaigns series by Django Wexler. I will note that in that series, Wexler shows attempted rape. But he never shows successful rape on screen.

Off screen, in a character’s backstory, yes. Marie Brennan has something to say about that too:

2. I need to motivate one of my characters.

. . . okay. But why rape? Why is that your go-to motivation? …

… time and time again, we have female characters being motivated by rape, and male characters being motivated by the rape and murder of their wives/sisters/daughters.

Try harder. Think about the emotional impact of everything else this character has experienced, and what else you can use if the current material isn’t enough. Ask yourself why rape is the best answer to this question, when it’s about as fresh as having a Dark Lord with Armies of Monstrous Minions as your villain.

In Wexler’s case, there is in fact a reason why rape is one motivator for Jane (not the only or probably the most central motivation, I’ll add). This is the case because being sold into slavery/marriage was the whole point of that home for girls where she and Winter were both held for part of their childhood. It wasn’t incidental. That institution set up everything about Winter’s backstory as well as Janes.

Being sold to that brute was not only a motivator — again, not the only one — for Jane; having Jane sold that way, and failing to save her, was a central motivator for Winter. So in this case, that element of the backstory ticks both boxes for the “time and time again” comment Marie Brennan makes.

Why it works: Lots of reasons, I think. It’s in the backstory; it’s not only non-explicit, it’s not shown and barely referred to; the rapist is killed because of his act; the victim is the ones who kill her attacker; Jane’s primary motivation comes from other issues that have only a tenuous relationship to that aspect of her backstory.

And most of all because of the complicated way the whole situation feeds into Winter’s backstory and into the relationship between Winter and Jane. The primary problem for Winter was that Jane asked her to murder the man for her and Winter couldn’t bring herself to even make a serious attempt to do that. Not only did that motivate Winter’s escape from the home, it became for her the central defining failure of her life. Then later, well, Winter’s and Jane’s shared background has a ton of ramifications and in fact the relationship between those two characters is arguably the central pillar of the whole series.

So, Brennan’s essay is definitely a good one and well worth reading. And Wexler’s series is definitely one I’d pick over Game of Thrones, not only because of treatment of rape in the respective series, but just because as far as I’m concerned The Shadow Campaigns is just a better epic fantasy.

In fact, it would be great to see it turned into a TV series. If we were voting on next epic fantasy series to be picked up for TV, I’d vote for it. I’d even actually watch it.

Please Feel Free to Share:

November 5, 2019

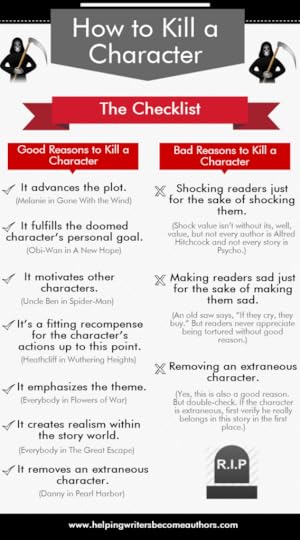

Killing your characters

Can you kill important characters? Sure. Happens all the time.

Should you? When does that work and when does it fail, or perhaps go over the top? Let’s take a look at various examples of SFF novels featuring the deaths of important secondary characters and/or the deaths of protagonists, and consider why those do or don’t work.

As it happens, I’m not personally too keen on authors who slaughter characters left and right for no good reason. I’m thinking here of Game of Thrones. It was one thing when Martin set the reader up to think Ned Stark was going to be an important protagonist and then killed the character early in the series. That was a way to break important assumptions for how the story was going to unfold. It increased tension in a good way, for a good reason — who else might seem too crucial to die, while actually headed for an early grave?

But besides that, as I recall, from time to time Martin also introduces a new pov character and then kills that character at the end of the chapter. I mean, what is even the point?

On a related note, personally, except in murder mysteries, I detest the trick where the author kills the pov character with whom he opens the book. When that happens with a new-to-me author, it’s probably going to be a DNF moment.

Even more annoying than that are authors who set out to manipulate you by introducing a very likable character specifically in order to kill her. (It’s always a “her.”) If this manipulation is too blatant, it’s a real turnoff. I’m thinking of all of Steven King’s recent books, here, where very likable characters are obviously present solely to function as tearjerkers upon their gratuitous deaths, which is why I eventually stopped reading King’s books.

However, it’s not like I’m opposed to character death per se. The pathos created by a sympathetic character’s death can be very useful when it’s done well and for a good reason. In a recent WIP, I deliberately killed a particular secondary character after going to some trouble to make the reader like him. Even though his death wasn’t at all important to the plot, it wasn’t gratuitous either; on the contrary, it was essential. I had to do it because without the death of that character, the deaths of a couple hundred other people would have passed without a blip on the reader’s emotional radar. They weren’t known, they were just a faceless mass. The death of the one character served as a proxy for all those deaths, giving that whole scene emotional heft it had completely lacked before.

I’ve killed other characters, of course, and I’m sure I’ll kill more in the future. Sometimes it’s necessary to get the plot to work and sometimes it’s necessary to add emotional weight and sometimes for some other reason — you know, there’s an infographic for this — here:

I think this is a very good infographic! Best touch: having “removes an extraneous character” on both sides of the graphic.

Perhaps somewhat iffy: while the death of a secondary character may be motivating to your primary protagonist, the modern author may wish to avoid having all the female characters exist solely to motivate the male protagonist through their abuse and/or death.

I will also just note, considering the above infographic, that if I’d known how The Great Escape ended, I probably wouldn’t have watched it. I prefer less realism and more survival in my WWII fictionalized novels and movies.

But, though I really like the above infographic, I believe that the whole thing can be boiled down to this: two things are always, always bad when killing a character —

a) The reader can see the strings you’re pulling. You should indeed do things for a reason, but your manipulation should not be nearly that visible.

and

b) Killing a dog. Sorry. Other sympathetic characters may have to die, but the dog should live happily ever after.

Incidentally, T. Kingfisher’s The Twisted Ones, which I’m about a quarter of the way through now, features a Very Good Dog. The dog is an important character AND important to the plot AND really well done, because Ursula Vernon / T. Kingfisher knows her dogs.

And right up near the beginning, the author makes it clear that the dog lives by throwing in a casual line: “… but because he’s a coonhound and all nose, we both survived.” or something like that. I bet that is not a chance occurrence. I bet she deliberately chose to let the reader know this up front, to avoid alienating those readers who won’t touch a book until they can be sure the dog lives.

I really like the story so far, by the way! Getting creepy, but without overt gore or anything of the kind. It reminds me just a bit of Sunshine by McKinley, even though it’s very different.

Please Feel Free to Share:

November 4, 2019

The magic of creativity

From Maggie Stiefvater, over at tor.com: Five Books About Artists and the Magic of Creativity

As a fantasy reader, I cut my teeth on stories of fairies stealing away ordinary musicians and returning them as troubled geniuses, weavers knotting the future into mystical tapestries, men climbing mountains and returning as poets with fraught and mystical tongues. …

Ooh, ooh, I have one! (Or several). But first let’s see what Maggie Stiefvater has picked:

Fire and Hemlock by DWJ.

Okay, well, I know that quite a few people pick this one out as their favorite story by Jones. I have to admit, it isn’t one that I go back to very often. I admire its structure, but I like nearly every other book of hers better than this one. Unlike Steifvater, who says, “High myth and dreary reality blend seamlessly on the ordinary streets of ‘80s Britain in this novel; music and magic are inseparable in it. Jones … has written many novels, but this is the one I return to the most. With its dreamy, tongue-in-cheek style, it feels more like a memory than a novel.”

Yes, well, I’ve read it a couple of times, but my favorites are Dogsbody and some of the Chrestomanci stories. And Derkholm. For the dreamy tone, I actually prefer The Spellcoats to Fire and Hemlock.

Anyway, after DWJ, Stiefvater picks out a couple of books I’ve heard of but haven’t read. Then this one:

Taran Wanderer by Lloyd Alexander

It has been so long since I read this series that I have honestly forgotten a lot about it. One of the things I’ve forgotten, apparently, is anything about music or making. Let me see … Stiefvater says: “When I first read this one as a child, I found it the most dull—why did I have to read about Taran apprenticing with various craftsmen and artists while sulking that he was probably unworthy for a princess? When I reread it as a teen, I loved it the best of all of them. Taran takes away a lesson from every artist and artisan and warrior he meets, and the hero he is in book five is because of the student he was in book four.”

Oh, yes, that brings it back. I actually liked this one from the beginning. I have always liked stories about learning to do stuff. When I hit a training montage kind of thing — a “time has passed, he learned all the stuff” transition in a novel — I feel a bit cheated. Or sometimes more than a bit. I like the learning part. I won’t say it can’t be drawn out over-long, but I will say that for my taste that seldom happens, even when the training part of the book takes up most of the story, as in CJC’s The Paladin. Or the entire story in Sherwood Smith’s A Stranger to Command.

I didn’t mean to pick out just stories where someone is learning the arts of war. That was just a coincidence. I loved the Harper Hall stories best when first read all the Pern books, and in large part that was probably because of Menolly learning to be a harper.

Okay, and the last of the ones Stiefvater picks — click through to see all five — is Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel.

I liked that one a lot. Here we’re talking about actors rather than musicians. Stiefvater says, “The end of the world has come and gone, illness ravaging the population, and what is left in its wake? In St. John Mandel’s vision of the end of the world: artists. Actors, to be precise. We have ever so many apocalypse stories that show us the ugly side of humanity, but Station Eleven stands out for highlighting the opposite. Yes, there are survivalists with shotguns and ugly truths in this version of the end of the world, but there’s also art, creativity, synthesis, the making of a new culture. …”

Of course we do see a lot of the end of the world too, as this story moves back and forth through time and shows the apocalypse as well as the post-apocalypse.

Okay! As always with a five-part list, I feel that a lot of good choices for this theme were left on the table. I don’t think it will be at all difficult to add five more, thus creating the proper ten-part list.

Given that last choice, I now have actors on the brain. I can immediately think of three SFF novels where actors are very important. None of them really meld magic and artistry, but neither does Station Eleven, so that’s fine.

6) The Dagger and the Coin series by Daniel Abraham, starting with The Dragon’s Path.

Several things about this novel put me off the series, though from time to time I think of going on with it. This latter impulse is due mainly to Master Kit, the leader of a troop of actors. The actors are a great component of the story and Master Kit is by far my favorite character in the story so far.

7) The Republic of Thieves by Scott Lynch.

The link goes to a post of mine about the book, so click through if you wish, but rest assured, acting and actors are at the heart of the story. In a couple different ways, actually, considering the overall plot.

8) Not the same as the apprenticeship volume of Taran Wanderer, but I instantly thought of Castle Behind Thorns by Merrie Haskell. Fabulous and unusual story, where the protagonist is by himself, fixing up a ruined castle, for quite a long time.

9) Melding music and magic? Come on! Obviously the very best example ever is Song for the Basilisk! Remember that dreamlike journey into Fairie and out again? Not to mention the opera that’s being planned, and trying to teach Damiet to sing on key, and, and, and … no comparison for pouring music and magic together into fantasy. Except maybe for The Bards of Bone Plain, and honestly I just never liked that one as well as Song.

10) Music … magic … let me see … I know I have another one on the tip of my tongue … oh, right:

Bardic magic! Dragon harps! Horns that sound when a stranger steps through your door! And so on.

Who’s got another choice for melding artistry into fantasy? Drop it in the comments.

Please Feel Free to Share: