J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 427

November 27, 2017

Monday Smackdown: Nine Republican Economists Being Unprofessional on Tax Reform Edition

First of all, note that nine and only nine would sign on to this letter.

That is not a large number.

Second, note that they do not analyze the deficit-increasing tax bill on display, but rather something else:

Robert J. Barro, Michael J. Boskin, John Cogan, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Glenn Hubbard, Lawrence B. Lindsey, Harvey S. Rosen, George P. Shultz, and John. B. Taylor: How Tax Reform Will Lift the Economy: "In the foregoing analysis, we assumed a revenue-neutral corporate tax change...

Third, note that they do not model and calculate but rather assert that changes in interest rates" will be small because "the United States operates in an international capital market":

...Deficit financing... increases federal debt and interest rates, all else equal. For the House and Senate Finance bills, this offset is likely to be modest, given that the United States operates in an international capital market, which means that the impact of changes in interest rates resulting from greater investment demand and government borrowing are likely to be relatively small...

Fourth, note that that assertion is wrong. The U.S. is not a small open economy. The U.S. is more than 1/3 of the international financial economy, so that long run world average interest rates will rise about 1/3 as much from bigger U.S. deficits as they would if the U.S. are a closed economy. And even in small open economies interest rates deviate substantially from the averages of the international capital market. International capital and goods mobility is far from perfect: we have known this for fifty years, and for fifty years standard modeling has produced large swings in exchange rates, trade flows, and domestic interest rates in short and medium runs that extend well beyond a decade.

Fifth, note that while they claim that "the impact of changes in interest rates will be "small", the metric they use to claim that the drag on growth from larger deficits will be small also labels the boost to growth that they see "small" as well. They see a 3% boost to GDP from lower capital taxes. From that you need to subtract a 1.5% reduction in GDP from deficit drag. You get a final 1.5% boost to GDP according to their modeling strategy if you do not sweep the deficit effects on saving under the rug

Sixth, note that that 1.5% boost is a boost to GDP, not to national income. By the time you have subtracted off the fact that foreigners will be paying less taxes to the U.S. Treasury, the effect on national income is in the range of zero.

Seventh, note that while they say that growth effects would "reduce the 'static cost' of the reforms', they do not say that it would reduce the "static cost' by much.

Unwillingness to quantify the dynamic offset on revenues, unwillingness to acknowledge the wedge between national income and domestic product, unwillingness to quantify the deficit drag on growth, simply wrong on the consequences of cross-border finance and trade, unwillingness to quantify what their (wrong) approach thinks the consequences of cross-border finance and trade are, unwillingness to actually analyze the bill at hand rather than something else, and inability to get more than nine economists to sign on���this is a document that documents, above all, the unwillingness of even highly partisan Republican economists to get on this particular train in any way that might produce pushback from their less-partisan peers.

Thus the way to understand this letter is to understand that its writing and publication has three goals:

The first point is to get at least some economists on record saying something that will be interpreted by Fox News and others as: "some economics say that the bill will provide a big boost the economy and also almost pay for itself".

The second goal is to avoid having to get even those some economists on record actually saying that the bill will provide a big boost the economy and also almost pay for itself.

The third goal is to thus get CNN and the New York Times out there saying "economists differ".

If you want a Republican economist's take that will actually inform you, you should go to Greg Mankiw: he is correct in his description of the current process and bill as being an "unworkable mess".

Yes. The New York Times is in hell, nor are we out of it....

Yes. The New York Times is in hell, nor are we out of it. What else do you want to know?

Steve M.: ALL THE WAYS THE NEW YORK TIMES IS DEFENDING THAT NAZI NORMALIZATION STORY: "I don't think it's 'indisputable' that we 'need to shed more light...

...on the most extreme corners of American life and the people who inhabit them...

if what that means is that we see extremists going to the grocery store and cooking pasta. If all you have to say as a reporter is that the Nazis next door are not cartoon villains, that's not "shedding light," because they are engaged in monstrous activity when they're not shopping for food and cooking and you're ignoring that. That's what we need to know about. Or we need to know what happens to people on the receiving end of what these Nazis do. Banality of evil? Stipulated. Don't waste our time on what we already know.

November 26, 2017

Should-Read: Mark Koyama: The End of the Past: "Temin���s...

Should-Read: Mark Koyama: The End of the Past: "Temin���s GDP estimates suggest that Roman Italy had comparable per capita income to the Dutch Republic in 1600...

...Schiavone... raises important points that I had fully not considered previously.... Aelius Aristides celebrating the wealth of the Roman empire in the mid-2nd century AD... a panegyric addressed to flatter the emperor but its emphasis on long-distance trade, commerce, manufacturing is highly suggestive. Such a speech is all but impossible to imagine in an predominantly rural and autarkic society. Aristides is painting a picture of a highly developed commercialized economy that linked together the entire Mediterranean and beyond. Even if he is grossly exaggerates, the imagine he depicts must have been plausible to his audience.

In evaluating the Roman economy in the age of Aristides, Schaivone notes that:

Until at least mid-seventeenth century Amsterdam, so expertly described by Simon Schama���the city of Rembrandt, Spinoza, and the great sea-trade companies, the product of the Dutch miracle and the first real globalization of the economy���or at least, until the Spanish empire of Philip II, the total wealth accumulated and produced in the various regions of Europe reached levels that were not too far from those of the ancient world...

This is the point Temin makes. Whether measured in terms of the size of its largest cities���Rome in 100 AD was larger than any European city in 1700���or in the volume of grain, wine, and olive oil imported into Italy, the scale of the Roman economy was vast by any premodern standard. Quantitively, then, the Roman economy looks as large and prosperous as that the early modern European economy. Qualitatively, however, there are important differences....

Roman history leaves no traces of great mercantile companies like the Bardi, the Peruzzi or the Medici. There are no records of commercial manuals of the sort that are abundant from Renaissance Italy... no political economy or ���economics���.... The most obvious institutional difference between the ancient world and the modern was slavery. Recently historians have tried to elevate slavery and labor coercion as crucial causal mechanism in explaining the industrial revolution. These attempts are unconvincing (see this post) but slavery certainly did dominate the ancient economy....

Schiavone���s chapter ���Slaves, Nature, Machines��� is a tour de force. At once he captures the ubiquity of slavery in the ancient economy, its unremitting brutality���for instance, private firms that specialized in branding, retrieving, and punishing runaway slaves���and, at the same time, touches the central economic questions raised by ancient slavery: to what extent was slavery crucial to the economic expansion of period between 200 BCE and 150 AD? And did the prevalence of slavery impede innovation?...

Schiavone suggests that ultimately the economic stagnation of the ancient world was due to a peculiar equilibrium that centered around slavery.... The apparent modernity of the ancient economy���its manufacturing, trade, and commerce rested largely on slave labor.... The ancient reliance on slaves as human automatons���machines with souls���removed or at least weakened, the incentive to develop machines for productive purposes.... There was also a specific cultural attitude....

None of the great engineers and architects, none of the incomparable builders of bridges, roads, and aqueducts, none of the experts in the employment of the apparatus of war, and none of their customers, either in the public administration or in the large landowning families, understood that the most advantageous arena for the use and improvement of machines���devices that were either already in use or easily created by association, or that could be designed to meet existing needs���would have been farms and workshops...

The relevance of slavery colored ancient attitudes towards almost all forms of manual work or craftsmanship. The dominant cultural meme was as follows: since such work was usually done by the unfree, it must be lowly, dirty and demeaning:

technology, cooperative production, the various kinds of manual labor that were different from the solitary exertion of the peasants on his land���could not but end up socially and intellectually abandoned to the lowliest members of the community, in direct contact with the exploitation of the slaves, for whom the necessity and demand increased out of all proportion... the labor of slaves was in symmetry with and concealed behind (so to speak) the freedom of the aristocratic thought, while this in turn was in symmetry with the flight from a mechanical and quantitative vision of nature...

Thus this attitude also manifest itself in the distain the ancients had for practical mechanics:

Similar condescension was shown to small businessmen and to most trade (only truly large-scale trade was free from this taint). The ancient world does not seem to have produced self-reproducing mercantile elites.... The phenomenon coined by Fernand Braudel, the ���Betrayal of the Bourgeois,��� was particularly powerful in ancient Rome. Great merchants flourished, but ���in order to be truly valued, they eventually had to become rentiers, as Cicero affirmed without hesitation: ���Nay, it even seems to deserve the highest respect, if those who are engaged in it [trade], satiated, or rather��, I should say, satisfied with the fortunes they have made, make their way from port to a country estate, as they have often made it from the sea into port. But of all the occupations by which gain is secured, none is better than agriculture, none more delightful, none more becoming to a freeman������ (Schiavone, 2000, 103)...

Such a cultural argument fits perfectly with Deirdre McCloskey���s claim in her recent trilogy that it was the adoption of bourgeois cultural norms and specifically bourgeois rhetoric that distinguished and caused the rise of north-western Europe after 1650....

The most advanced economies of early modern Europe, say England in 1700, were on the surface not too dissimilar to that of ancient Rome. But beneath the surface they contained the ���coiled spring���, or at least the possibility, of sustained economic growth���growth driven by the emergence of innovation (a culture of improvement) and a commercial or even capitalist culture. According to Schiavone���s assessment, the Roman economy at least by 100 CE contained no such coiled spring.

We are not yet at the point when we can decisively assess this argument. But the importance of culture and the manner in which cultural and material factors interacted is clearly crucial. The argument that the slave economy and the easy assumptions of aristocratic superiority reinforced one another is a powerful one. For whatever historical reasons these cultural elements in the Roman economy were relatively undisturbed by the rise of merchants, traders and money grubbing equites. Likewise slavery did not undermine itself and give rise to wage labor.

Why this was the case can be left to future analysis. The full answer to the question why this was the case and a more careful consideration of the counterfactual ���could it have been otherwise��� are topics deserving their own blog post.

Note to Self: Getting in Touch with My Inner Austrian: Toy Stochastic Processes Edition

Note to Self: Getting in Touch with My Inner Austrian: Memo to Self: A Start of a Model...: How can you be an Austrian, and yet have big swings in the desired capital stock���and thus bigger swings in the desired rate of investment���without having to have massive shocks to the current level of technology? How can you get a big downward shock to desired investment without committing yourself to massive technological amnesia?

This is how:

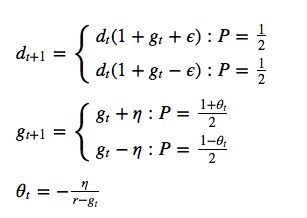

You can do it with two shocks to the dividends paid on a unit of capital: a shock $ \epsilon $ to the level of $ d_{t} $ and a shock $ \eta $ to the growth rate $ g_{t} $ of $ d_{t} $, thus:

Why this dividend process? Because if we then have a required expected rate of return r and a value function $ V(d_{t},g_{t}) = d_{t}v(g_{t}) $, then the one-period arbitrage condition:

$ (1+r)d_{t}v(g_{t}) = d_{t} + E_{t}\left(d_{t}{v(g_{t+1})}\right) $

leads us to

$ (1+r)v(g_{t}) = 1 + \left(\frac{1+g_{t}}{2}\right)\left((1+\theta_{t}){v(g_{t} + \eta)} + (1-\theta_{t}){v(g_{t} - \eta)}\right) $

$ (r-g_{t})v(g_{t}) = 1 + \left(\frac{1+g_{t}}{2}\right)\left((1+\theta_{t}){v(g_{t} + \eta)} + (1-\theta_{t}){v(g_{t} - \eta)} - 2v(g_{t})\right) $

Then simply postulate:

$ v(g_{t}) = \frac{1}{r-g_{t}} $

And find:

$ 1 = 1 + \left(\frac{1+g_{t}}{2}\right)\left(\frac{1+\theta_{t}}{r - g_{t} - \eta} + \frac{1-\theta_{t}}{r - g_{t} + \eta} -\frac{2}{r - g_{t}}\right) $

$ 0 = \left(\frac{(1+\theta_{t})(r - g_{t} + \eta)}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} + \frac{(1-\theta_{t})(r - g_{t} - \eta)}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} \right) $

$ 0 = \frac{r - g_{t} + \eta + \theta_{t}r - \theta_{t}g_{t} + \theta_{t}\eta + r - g_{t} - \eta - \theta_{t}r + \theta_{t}g_{t} + \theta_{t}\eta}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} - \frac{2}{r - g_{t}} $

$ 0 = \frac{2(r - g_{t}) + 2\theta_{t}\eta}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} - \frac{2}{r - g_{t}} $

$ \frac{1}{r - g_{t}} = \frac{(r - g_{t}) + \theta_{t}\eta}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} $

$ 1 = \frac{(r - g_{t})^2 + \theta_{t}\eta({r - g_{t}})}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} $

$ - \eta = \theta_{t}({r - g_{t}}) $

$ \theta_{t} = - \frac{\eta}{r - g_{t}} $

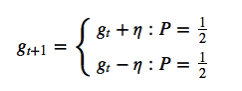

Why all the $ \theta_{t} $ terms? Because you cannot have the expected growth rate of dividends $ g_{t} $ random walk. There is some chance it will random walk upwards and valuations will explode, and a chance of valuations exploding in the future means that valuations explode now (if they haven't already exploded). If you just have:

Then if you assume the Gordon equation for your value function, you find that it is wrong, for your arbitrage equation leads to:

$ 1 = 1 + \left(\frac{1+g_{t}}{2}\right)\left(\frac{1}{r - g_{t} - \eta} + \frac{1}{r - g_{t} + \eta} -\frac{2}{r - g_{t}}\right) $

which then generates the unpleasant:

$ 0 = \left(\frac{r - g_{t}}{(r - g_{t})^2 - (\eta)^2} -\frac{1}{r - g_{t}}\right) $

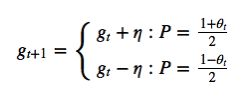

Writing, instead:

with:

$ \theta_{t} = - \frac{\eta}{r - g_{t}} $

imparts just enough downward drift to the random walk of the growth rate $ g_(t) $ to make the Gordon equation the right valuation equation.

You can complain that this process is not stable: with a constantly-applied downward drift to the growth rate, for a large enough valute of $ t $ it is almost surely the case that $ r - g-{t} $ is very large, and thus that valuations are almost surely very low relative to diviedns because dividends will then be almost surely shrinking fast.

So sue me...

(No calculations yet)

Background

Previous posts:

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2017/11/monday-smackdown-trying-to-get-in-touch-with-my-inner-austrian-was-a-bad-mistake-in-2004-and-a-horrible-misjudgement-in-200.html

This ipynb: https://www.dropbox.com/s/3wsggjajbm897zr/2017-11-26%20Getting%20in%20Touch%20with%20My%20Inner%20Austrian.ipynb?dl=0

Monday DeLong Smackdown: Trying and Failing to Get in Touch with My Inner Austrian Back in 2004...

That I never figured out how to write this paper is deserving of a smackdown. Why did I never figure out how to write it? Because I never figured out what to say, or what the answer was:

Hoisted from 2004: Getting in Touch with My Inner Austrian: A Still-Unwritten Paper: Fragment of an Unfinished Ms.: Part II of an unfinished paper, "After the Bubble." The paper currently lacks Parts I, III, IV, V, and VI:

II. Aggressively Expansionary Monetary Policy and Macroeconomic Vulnerabilities:

Let us begin with a passage from Mussa (2004), "Global Economic Prospects: Bright for 2004 but with Questions Thereafter" (Washington: Institute for International Economics: April 1), in which Michael Mussa writes about global financial imbalances:

Michael Mussa: Policy interest rates are exceptionally low in most industrial countries: zero in Japan and Switzerland, 1 percent in the United States, 2 percent in the euro area, and at or near historic lows in the United Kingdom and Canada.... The very low level of policy interest rates is an imbalance (relative to normal conditions) that reflects exceptionally easy monetary policies to combat economic weakness.

This policy imbalance poses an important challenge for the future conduct of monetary policy. Situations of low policy interest rates and low inflation tend to be associated with unusual inertia in the processes of general price inflation, which makes traditional indicators of rising inflationary pressures less reliable as measures of the need to begin to tighten monetary conditions. Also, these situations tend to be associated with high valuations of equities, real estate, and long-term bonds, which can become fertile ground for large, unsustainable increases in asset prices. In this situation, if monetary policy is tightened too much too soon (perhaps because of worries about unsustainable increases in asset prices), the result can be an unnecessary asset market crunch and economic slowdown, and monetary policy may have relatively little room to ease in order to counteract this outcome.

On the other hand, if monetary policy remains too easy for too long (perhaps because subdued general price inflation gives no clear signal of the need for monetary tightening), then large asset price anomalies may develop before corrective action is taken. The monetary authority would then confront the grim choice of trying to keep an unsustainable asset price bubble alive or trying to combat the collapse of such a bubble without a great deal of room for monetary easing.

A further concern related to the general monetary policy imbalance in the industrial countries is its effect on emerging market economies. Interest rate spreads for emerging market borrowers have contracted substantially and flows of new credit have increased. The boom in emerging market credit has not yet reached the frenzy of the first half of 1997, but it is headed in that direction. Another major series of emerging market financial crises (such as 1997-99) does not seem likely in the near term in view of the very low level of industrial country interest rates and the favorable global economic environment for emerging market countries. By 2005 or 2006, however, either upward movements in industrial country interest rates or deterioration of market perceptions of the economic and financial stability of some emerging market countries could trigger another round of crises.

Mussa is warning that the high asset prices produced by very low interest rates pose dangers that may turn out to be substantial. One way to read Mussa's warning is as a polite--a very polite--criticism of Alan Greenspan's self-praise of his own low interest-rate policy contained in Greenspan (2004), "Risk and Uncertainty in Monetary Policy" (Washington: Federal Reserve Board: January 3):

Alan Greenspan: Perhaps the greatest irony of the past decade is that... success against inflation... contributed to the stock price bubble .... Fed policymakers were confronted with forces that none of us had previously encountered. Aside from the then-recent experience of Japan, only remote historical episodes gave us clues to the appropriate stance for policy under such conditions. The sharp rise in stock prices and their subsequent fall were, thus, an especial challenge to the Federal Reserve. It is far from obvious that bubbles, even if identified early, can be preempted at lower cost than a substantial economic contraction and possible financial destabilization--the very outcomes we would be seeking to avoid.... The notion that a well-timed incremental tightening could have been calibrated to prevent the late 1990s bubble while preserving economic stability is almost surely an illusion.

Instead of trying to contain a putative bubble by drastic actions with largely unpredictable consequences, we chose, as we noted in our mid-1999 congressional testimony, to focus on policies "to mitigate the fallout when it occurs and, hopefully, ease the transition to the next expansion."

During 2001, in the aftermath of the bursting of the bubble and the acts of terrorism in September 2001, the federal funds rate was lowered 4-3/4 percentage points. Subsequently, another 75 basis points were pared, bringing the rate by June 2003 to its current 1 percent, the lowest level in 45 years. We were able to be unusually aggressive in the initial stages of the recession of 2001 because both inflation and inflation expectations were low and stable. We thought we needed to be, and could be, forceful in 2002 and 2003 as well because, with demand weak, inflation risks had become two-sided for the first time in forty years.

There appears to be enough evidence, at least tentatively, to conclude that our strategy of addressing the bubble's consequences rather than the bubble itself has been successful. Despite the stock market plunge, terrorist attacks, corporate scandals, and wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, we experienced an exceptionally mild recession--even milder than that of a decade earlier. As I discuss later, much of the ability of the U.S. economy to absorb these sequences of shocks resulted from notably improved structural flexibility. But highly aggressive monetary ease was doubtless also a significant contributor to stability...

Greenspan is confident that raising interest rates and thus raising the unemployment rate during the bubble of the late 1990s would have been the wrong policy, and that aggressively lowering interest rates after the bubble was the right policy. Lowering interest rates cushioned falls in bond prices. Lowering interest rates made use of bond financing for investment more attractive. Lowering interest rates boosted bond and real estate prices, induced households to refinance, and so provided a powerful spur to consumption spending that largely offset the post-bubble fall in investment spending. In Greenspan's view, the aggressive lowering ofinterest rates was exactly the right thing to do in the aftermath of the bubble to shift spending from investment to consumption and so to keep the economy not far from full employment.

Mussa says: not so fast. Very low interest rates, coupled with assurances from high Federal Reserve officials that interest rates will stay very low for substantial periods of time, produce a situation in which the prices of long-duration assets���long-term bonds, growth stocks, and real estate���climb very high. What goes up may come down, and may come down rapidly. And should some class of asset prices come down rapidly and should it turn out that many debtors in the economy go bankrupt because their assets have lost value, serious financial crisis will result. The price of using exceptionally easy money to keep the collapse of the dot-com bubble from turning into a depression has been the creation of a three-fold vulnerability:

If the assets the prices of which collapse when interest rates start to rise are emerging-market debt, then the memories of the 1990s and increasing risk will induce large-scale capital flight from the periphery to the core���an echo of the East Asian financial crises of 1997-1998.

If the assets the prices of which threaten collapse when interest rates start to rise are domestic bond and real estate holdings that have been pushed to unsustainable levels by positive-feedback "bubble" buying, then the "monetary authority would... confront the grim choice of trying to keep an unsustainable asset price bubble alive or trying to combat the collapse of such a bubble without a great deal of room for monetary easing" to keep real estate and bond prices from falling far and fast.

"If monetary policy is tightened too much too soon" (presumably because of fears of positive-feedback "bubble" buying), the result may be a credit crunch and a recession���with no guarantee that a reversal of the monetary policy tightening will undue the effects of the credit crunch. I do not believe that many economists would say that Mussa's fears about the potential macroeconomic vulnerabilities created by the low interest-rate policy the Federal Reserve has pursued since the end of the dot-com bubble are unreasonable. (Few, however, carry their alarm to the degree that Stephen Roach of Morgan Stanley does.)

And Mussa expresses them in a coherent language���one in which sustained rises in asset prices induce positive-feedback trading that "bubbles" prices above fundamentals, one in which what goes up comes down rapidly, one in which large sudden falls in asset prices produce chains of bankruptcy and raise risk and default premia enough to threaten to cause deep recessions. The language has echoes of the great Charles P. Kindleberger's (1978) Manias, Panics, and Crashes (New York: Basic Books), and of earlier writings about the consequences of excessive money-printing: "inflation, revulsion, and discredit."

But what Mussa's assessment of risks lacks is a model. And without a model, we have a hard time assessing his argument. Alan Greenspan frightened away the Evil Depression Fairy in 2000-2002 by promising not that he would let the Evil Fairy marry his daughter but by promising high asset prices���unsustainably high asset prices���for a while. Whether this was a good trade or not depends on the relative values of the risks avoided and the risks accepted. And to evaluate this requires a model of some sort...

References:

Alan Greenspan (2004), "Risk and Uncertainty in Monetary Policy" (Washington: Federal Reserve Board: January 3).

Michael Mussa (2004), "Global Economic Prospects: Bright for 2004 but with Questions Thereafter" (Washington: Institute for International Economics: April 1)..."

Should-Read: Alice Sola Kim: @alicek on Twitter: "New Yor...

Should-Read: Alice Sola Kim: @alicek on Twitter: "New York Times: nazi who are you??? what do you want?...

...NAZI: white power, cops even more murdering black people w impunity, feudalism, hitler was v v chill. NYT: but nazi what do you want? NAZI: i just said. NYT: oooooo so what are you putting in that pasta you're making, looks yum.

Must-Read: As I repeatedly say, people are spending a lot...

Must-Read: As I repeatedly say, people are spending a lot of time on their cellphones and such doing things that would have been very expensive or impossible back in 1980. That doesn't speak to the distributional point at all���the rich (at least the young rich) benefit more from cheap electronic devices not just by being able to afford more of them but because they are information-age force multipliers for how to better spend your money. But it does speak to the average growth point:

Dylan Matthews: You're not imagining it: the rich really are hoarding economic growth: "With... 'distributional national accounts'... exactly where economic growth is going...

...and how much each group is seeing its income rise relative to the overall economy.... Saez, Piketty, and Zucman... answers basically all of the conservative critiques.... Incomes... employer-provided health care, pensions, and other benefits... taxes and government transfer programs... changes in income among adults, rather than households or tax units... the slower-growing inflation metric, rather than CPI. And what do they find? This:

Some Fairly-Recent Must- and Should-Reads...

Paul Krugman: The Transfer Problem and Tax Incidence: "These days, what passes for policymaking in America manages to be simultaneously farcical and sinister, and the evil-clown aspects extend into the oddest places...

Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles: The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality: "For years, America has been plagued by slow economic growth and increasing inequality...

Mark Koyama: Could Rome Have Had an Industrial Revolution?: "First... those... think... market expansion is sufficient for sustained economic growth...

Martin Wolf: A Republican tax plan built for plutocrats: "How does a political party dedicated to the material interests of the top 0.1 per cent of the income distribution win and hold power in a universal suffrage democracy?...

Paul Krugman (2009): The Obama Gaps: "The bottom line is that the Obama plan is unlikely to close more than half of the looming output gap, and could easily end up doing less than a third of the job...

Stan Collender: GOP Tax Bill Is The End Of All Economic Sanity In Washington: "The GOP tax bill will increase the federal deficit by $2 trillion or more over the next decade (the official estimates of $1.5 trillion hide the real amount with a witches' brew of gimmicks and outright lies)...

Greg Leiserson: The Tax Foundation���s score of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: "First, the Tax Foundation appears to incorrectly model the interaction between federal and state corporate income taxes...

Martin Sandbu: Who should govern the euro?: "I have long argued against further centralisation of fiscal and structural policies, and proposed that some autonomy should instead be returned to the national level...

Justin Wolfers: @justinwolfers on Twitter: "The University of Chicago surveyed 42 leading economists and found exactly one who believes the Republican claim that their tax bill will grow the economy. http://www.igmchicago.org/surveys/tax-reform-2"

Ned Phelps: Nothing Natural About the Natural Rate of Unemployment: "A compelling hypothesis is that workers, shaken by the 2008 financial crisis and the deep recession that resulted...

Some Fairly-Recent Links:

Adam Serwer: The Nationalist's Delusion: "Trump���s supporters backed a time-honored American political tradition, disavowing racism while promising to enact a broad agenda of discrimination..."

Rudyard Kipling: The Janeites

Simon Wren-Lewis: Austerity and mortality: "You would think that a combination of the data and these studies would prompt the government to at least investigate what is happening, but they have so far done nothing. Perhaps they know what the result of any investigation would be..."

Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji: Behavioural economics is also useful in macroeconomics

Matt Townsend, Jenny Surane, Emma Orr and Christopher Cannon: America���s ���Retail Apocalypse��� Is Really Just Beginning

Highlighted | Teaching | Reading, Videos, etc.

Should-Reads:

Mark Koyama: Could Rome Have Had an Industrial Revolution?: "First... those... think... market expansion is sufficient for sustained economic growth...

Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles: The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality: "For years, America has been plagued by slow economic growth and increasing inequality...

November 25, 2017

Should-Read: Mark Koyama: Could Rome Have Had an Industri...

Should-Read: Mark Koyama: Could Rome Have Had an Industrial Revolution?: "First... those... think... market expansion is sufficient for sustained economic growth...

...They will be inclined to favorably quote Adam Smith from his lectures on jurisprudence that ���Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice���. Many libertarian-learning economists are in this category but few active economic historians. Second... colonial empires or natural resources like coal were crucial... the ���world systems��� theory of Immanuel Wallerstein. Perhaps the most sophisticated exponent is Ken Pomeranz... little support among economic historians. Third... ultimately only innovation can explain the transition to modern economic growth... the majority of economic historians... those who seek to explain the increase in innovation in purely economic terms and those who... argue that the answer has to be sought elsewhere, perhaps in something that can be broadly defined as culture.... Deirdre McCloskey and Joel Mokyr... agree that the inventive and enterprising spirit that characterized 18th century England cannot be explained in terms of simple incentives... argue that it required recognition of ���Bourgeois Dignity��� or a ���Culture of Growth���.

Adherents of the... view that trade, commerce, and market development were... sufficient... should find the Roman Industrial Revolution counterfactual highly appealing.... The Roman empire... had its colonies... a periphery to exploit... little intrinsic reason why it should have been less successful than the early modern world system in generating economic growth....

Those persuaded by Bob Allen���s high wage theory of the British Industrial Revolution should be at least intrigued by Dale���s alternative Roman history.... If factor prices were crucial to British industrialization, then could there have been a Roman industrial revolution under similar conditions?... But... any such break-though would have to have come in the 2nd century BCE, a period of rapid economic change, urbanization, and commercialization.... Regardless of whether this is right, there is no doubt that the demand for slaves soared after 200 BCE, and that their ready supply encouraged landlords to practice commercial agriculture on a vast scale. Such an economy was ill-suited for modern economic growth....

McCloskey and Mokyr suggest greater skepticism.... The more one buys into Mokyr���s emphasis on the importance of a competitive Republic of Science, the less likely is it that the Roman empire would have offered a conducive environment for science and innovation..... Similarly, I am not aware of evidence of the kind of rhetorical change in attitudes towards commerce in the Rome world that McCloskey documents in the 17th century Dutch Republic or 18th century England.... I���ve speculated in an earlier post on the ways in which slavery and other Roman institutions reinforced a cultural ethos that was hostile to trade-based economic betterment (here). But I would be eager to read counter evidence. Perhaps specialists do know of evidence of a change in Roman attitudes to commerce during this period?

All of this suggests that a better understanding of why sustained or modern economic growth did not occur during earlier ���efflorescences��� can help us better understand which factors were important in the explaining the transition that did take place after 1800...

Should-Read: I would conceptualize this differently. It i...

Should-Read: I would conceptualize this differently. It is not a "breakdown" of democratic governance that has allowed "wealthy special interests to capture the policymaking process". Interests have always captured the policymaking process. (i) Sometimes these interests are broad coalitions interested in (progressive) redistribution. (ii) Sometimes these interests are (narrower) interests interested in promoting entrepreneurship, enterprise, and wealth. And (iii) sometimes these interests are (narrow) interests interested in negative sum policies that drive their own enrichment. Interests of type (i) promote the general welfare according to standard utilitarian theory. Interest of type (ii) promote the general welfare by enriching the economy. It is interests of type (iii) that are the problem. And the question is: why does it appear that interests of type (iii) are more powerful now than they used to be?

Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles: The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality: "For years, America has been plagued by slow economic growth and increasing inequality...

...Yet economists have long taught that there is a tradeoff between equity and efficiency-that is, between making a bigger pie and dividing it more fairly. That is why our current predicament is so puzzling: today, we are faced with both a stagnating economy and sky-high inequality. In The Captured Economy, Brink Lindsey and Steven M. Teles identify a common factor behind these twin ills: breakdowns in democratic governance that allow wealthy special interests to capture the policymaking process for their own benefit. They document the proliferation of regressive regulations that redistribute wealth and income up the economic scale while stifling entrepreneurship and innovation. When the state entrenches privilege by subverting market competition, the tradeoff between equity and efficiency no longer holds.

Over the past four decades, new regulatory barriers have worked to shield the powerful from the rigors of competition, thereby inflating their incomes-sometimes to an extravagant degree. Lindsey and Teles detail four of the most important cases: subsidies for the financial sector's excessive risk taking, overprotection of copyrights and patents, favoritism toward incumbent businesses through occupational licensing schemes, and the NIMBY-led escalation of land use controls that drive up rents for everyone else.

Freeing the economy from regressive regulatory capture will be difficult. Lindsey and Teles are realistic about the chances for reform, but they offer a set of promising strategies to improve democratic deliberation and open pathways for meaningful policy change. An original and counterintuitive interpretation of the forces driving inequality and stagnation, The Captured Economy will be necessary reading for anyone concerned about America's mounting economic problems and the social tensions they are sparking.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers