J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 376

April 14, 2018

Should-Read: Justin Fox is right in noting that Paul Ryan...

Should-Read: Justin Fox is right in noting that Paul Ryan was always running a con game���that his aim was a more unequal country with lower taxes on the rich, not a country in which the federal government balanced its budget. But I would quarrel slightly with how he sets up this article. "Entitlement crisis" is a political framing that appeals not just to "very wealthy people and/or those with excellent health insurance": it also appeals to lazy centrist journalists with no understanding of demography or policy, and no desire to learn. We never had���and do not have���a Social Security crisis. We had���but apparently no longer have (but it may return)���a health care cost explosion crisis. We still have a we-pay-too-much-for-the-health-care-we-as-a-country-get crisis. "Entitlement crisis" leads us away from getting value for our social insurance spending, and toward an unequal and unhappy society: Justin Fox: Paul Ryan's Roadmap Was an Epic Fiscal Failure: "Paul Ryan did not cause the financial crisis.��He has nonetheless failed pretty spectacularly...��his actions have made the situation much worse than it had to be...

...I pin this on two main flaws in his approach: One has to do with the term "entitlement crisis," the other with tax policy. The big problem with "entitlement crisis" is that it's a political framing designed to appeal only to very wealthy people and/or those with excellent health insurance and retirement plans.... Improving��Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid so that they can keep delivering benefits is a political project that, while fraught with pitfalls, has a chance of eventual success. Hacking at them to avert an "entitlement crisis" decades in the future appears to be a non-starter. The reason I keep putting "entitlement crisis" in quotes is, first, that "social insurance" better describes the programs than "entitlements" does and, second, that projected increases in��social spending��alone��are unlikely to bring on a crisis. It��is increasing government spending without also increasing government revenue that could, eventually,��cause trouble....

Ryan got his way on tax��cuts while��making no progress whatsoever on that "entitlement crisis." A 0.8��percent-of-GDP drop in tax revenue isn't the end of the world. It is, however, a move in the wrong direction if you're worried about growing fiscal imbalances.... Raising the tax burden, though, was never part of Paul Ryan's plan. He wasn't even willing just to��hold it constant. Which��would seem to mean that he was never��all that serious about fixing America's fiscal ills...

April 13, 2018

Should-Read: When 70% of newly employed workers are peopl...

Should-Read: When 70% of newly employed workers are people who were not previously looking for a job, defining the labor force as the sum of employed and actively searching not employed makes very little sense: Josh Bivens: The fuzzy line between ���unemployed��� and ���not in the labor force��� and what it means for job creation strategies and the Federal Reserve: "Jobless people are classified into... either unemployed or not in the labor force...

...The unemployment rate is defined as the number of unemployed workers divided by the sum of employed and unemployed workers (or, the labor force). This rate tries exactly to capture what share of the adult population wants work, but hasn���t found it. This is why it is the most commonly referenced measure of ���slack��� in the labor market.... [But] the share of newly employed workers who were previously not searching for work is always high���well over half. Second, recent years have seen this share hit historic highs.... Because more and more jobs are being filled by people claiming to not have been looking for work it seems like the unemployment rate is becoming less useful as a clear-cut measure of labor market slack���this means we shouldn���t rely on it alone to decide whether or not the economy is at full employment.... It seems like Americans have plenty of appetite for new jobs (and particularly for good jobs). This means we should still be thinking hard about strategies for job creation���like I did in a recent paper. Finally, we don���t need policymakers who are committed to slowing the economy because they think unemployment has fallen low enough. Instead, we need policymakers willing to aggressively test just how fast the economy can grow before sparking inflation. The most important policymakers in this regard are the Federal Reserve, and this makes the next pick to head the Federal Reserve Bank of New York crucially important...

Should-Read: Jag Bhalla: The Epistemic Vigilance We Evolv...

Should-Read: Jag Bhalla: The Epistemic Vigilance We Evolved To Do Well: "Confirmation Bias Isn���t a Bug, It���s Operator Error...

...In _The Enigma of Reason+, Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber (M&S), articulate an ���argumentative theory of reasoning.��� Their ���interactionist��� views contrast sharply from the prevailing individualist ���intellectualism.��� M&S call confirmation bias���discounting facts that contradict your beliefs���a ���well-established but ill-explained��� pattern which actually has evolutionary advantages. An analogy between reason and sight can enlighten here. Eyesight isn���t a direct window onto reality. It detects limited wavelengths, needs many interpretative steps between received light and sight, and suffers optical illusions (that are tellingly not survival-threatening). Likewise, reason isn���t an all-seeing, impartial, objective logic machine (roughly what intellectualist Enlightenment reason-lovers like Descartes and Kant believed). Our brains are built and ���biased��� to enable evolutionarily useful behaviors. And solving abstract logic problems is an evolutionary novelty (e.g., only possible after the invention of the technology of writing). So reason evolved mainly ���to resolve the problems posed by living in collaborative groups.���...

M&S argue that reason���s two main functions, self-justification and persuasion, are tools ���for social action.��� But, they emphasize, there���s no evolutionary sense in being predisposed to pigheadedly sticking to your beliefs. You���re often better off changing your mind and using better ideas from trusted others (cognitive division of labor). So we evolved to be persuadable (by sufficiently good, trustworthy, reasons), as M&S describe in chapter 15 ���The Bright Side of Reason.��� M&S���s argumentative theory is often misrepresented as reason being like your inner lawyer���s win-at-all-costs ���weapon.��� But good lawyers know when to concede to stronger arguments. They negotiate in their clients��� better interests. And M&S say we have two inner lawyers, one very vigilant about reasons given by others, another lazy one arguing our side (with a sensible laziness). Not thinking too hard about your first justification and relying on the ���epistemic vigilance��� of co-reasoners is often a good division of ���cognitive labor,��� that efficiently generates better decisions (= clearly adaptive, if you can avoid being manipulated or misinformed).We���re well adapted for collective reasoning (unavoidably cooperative, self-deficient lives). And cognitive individualism is a recent, incoherent idea.

There���s much more in _The Enigma of Reason _(e.g., intuition���s role in all reasoning, or countering ���dual systems��� views, see Kahneman). And more work is needed (e.g. on trust, power, and intuition-shifting processes) but M&S���s work���perhaps better called the ���negotiative theory of reasoning��� or ���social theory of reasoning������ represents progress. Individualist Enlightenment thinkers mostly haven���t enlightened us about our inalienably social minds. Rather, the ���Age of Reason��� has tended to promote unempirical, unevolutionary, over-rationalist, over-individualist thinking (=delusions). Clearer thinkers aren���t blinkered by the aspirational projections of solitary geniuses. They see how extensive cognitive division of labor, and reliance on the minds of others, means we exceed the capabilities of our individual minds...

Should-Read: Yes, the African-American experience puts th...

Should-Read: Yes, the African-American experience puts the lie to any claim that it is "class not race" that is the overwhelmingly important factor. Any other questions?: Liz Hipple: New research on the relationship between race, place, and opportunity in the United States: "Raj Chetty and fellow researchers Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie R. Jones, and Sonya R. Porter released... ���Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective���...

...The paper analyzes the impact of race on intergenerational mobility, that is, the chances that children will earn more���or less���than their parents when they grow up.... Even when black and white boys are raised in families with similar incomes, black boys go on to earn less than white boys. This difference is noticeable and persistent across all incomes for boys, whereas there���s almost no discernable difference among girls. In fact, black girls go on to earn slightly more than white girls raised in families with a similar income. This raises serious questions about why outcomes vary across gender...

Globalization: What Did Krugman Miss?: DeLong Morning Coffee Podcast

Wednesday night at Ars Technica LIVE! at Eli's Mile High Club in Oakland���located beneath where the eight-lane Interstate 580 crosses the ten-lane California Highway 24���there were three demands from the People of the Internet Appearing in Meatspace for a return of the Morning Coffee podcast.

So why not?

Globalization: What Did Krugman Miss?: DeLong Morning Coffee Podcast:

Paul Krugman has a very nice short ���framework for thinking about globalization and the world��� piece derived from a talk he gave at the IMF last fall.

But���

Globalization: What Did Krugman Miss?: DeLong Morning Coffee Podcast

The easiest way to create podcasts appears to be to wander around the campus dictating things to Wavelength which then automatically posts them to the very interesting micro.blog: https://delong.micro.blog/2018/04/12/globalization-what-did.html

Text: http://www.bradford-delong.com/2018/03/globalization-what-did-paul-krugman-miss.html

Should-Read: Smart: Jonathan Chait: Trump Attacks Comey f...

Should-Read: Smart: Jonathan Chait: Trump Attacks Comey for Handing Him the Presidency: "Comey all but confirms the Democrats��� complaints.... He considered Clinton a lead-pipe cinch to win...

..."It is entirely possible that, because I was making decisions in an environment where Hillary Clinton was sure to be the next president, my concern about making her an illegitimate president by concealing the restarted investigation bore greater weight than it would have if the election appeared closer or if Donald Trump were ahead in all polls,��� he confesses. Contemporaneous text messages between agents assigned to the Clinton case confirm that the agency was acting as though Clinton was certain to win.... But the race was close enough that the shock of Comey���s announcement put her small lead in serious danger....

Comey���s decision can at least be understood, if not defended, by the context in which he operated. The belief that Clinton would certainly win was not reflected in hard-headed data journalism by sources like FiveThirtyEight... but it was the assumption of reporters framing the campaign. More importantly... the Republican Party has spent decades building up a partisan news environment capable of turning nonevents into imagined first-tier scandals. Conservatives spent years whipping up outrage at the ���IRS scandal,��� which was nothing more than the agency���s attempt to enforce murky campaign finance law against both liberal and conservative activists alike, as a sinister Obama plot to crush his enemies. They did the same with Benghazi, a case of a bureaucracy caught flat-footed by a terrorist attack, which Republicans depicted as a sinister plot to mislead the public, or even worse.... Clinton email...was not a nonstory... [but] a cabinet official, concerned about privacy, disregarding official instructions on email protocol. Had one of Trump���s cabinet members done the same, it would not rise to one of the ten worst scandals of the week in Trump���s slowest news week. But it was not a pure figment of the right-wing imagination.

Earlier in the summer, Comey had publicly announced he would not press charges, a decision any fair-minded FBI Director would have made. But he went out of his way to scold her, so as to avoid charges of favoritism. Even so, Republicans denounced both Clinton and Comey in hysterical terms.... The Republican party���s derangement... loomed over Comey when he made this decision.... In Comey���s mind, bending procedure and announcing he was investigating a candidate was an acceptable price to pay to avoid the opposite: years of hearings and delegitimization that would surely follow Clinton���s expected election. The fact that he accommodated the GOP���s refusal to accept the rules of the game is what put Comey in his present situation... [and] given Trump the pretext he is now using to discredit Comey. How can you trust a man, he now asks, who bent to the demands of my party? The Republican will to power that Comey thought he could placate is now being brought to bear upon him in a far more brutal and dangerous way. Comey thought in October 2016 he was averting a crisis to the system. He was merely sowing the wind...

Should-Read: The eminent Robert Skidelsky identifies thre...

Should-Read: The eminent Robert Skidelsky identifies three groups of economists who gave what ex post was clearly bad advice, and bad advice that mattered about fiscal policy, from 2009 on:

Alberto Alesina and company with their "expansionary austerity" doctrines,

Ken Rogoff and company with their "short-term-pain-for-long-run-gain" doctrines, and

Ricardo Haussman and company with the "no choice but austerity" doctrines.

All three groups, however, had reasons for their arguments and were thinking hard���albeit, in my view, not as hard and as deeply as they ought to have and had a responsibility to do���and genuinely believed what they were putting forward.

There were also three groups of economists giving bad advice who either did not believe what they were saying or had done no thinking at all:

Robert Lucas and company with his "nothing to apply a multiplier to" ideological and unfounded claims that fiscal policy could never be effective;

John Taylor, Marvin Goodfriend, and company with their Bernanke's monetary expansion will produce currency debasement and inflation but will not boost employment; and

a whole host of professional Republicans who ought to have been backing up Bernanke's plans for further monetary stimulus and his call for an end to fiscal austerity headwinds, but were instead very quiet, as Elmer Fudd would say, in part at least not to annoy political masters in the Republican Party.

I think the economics profession could have played a useful role in helping to manage the recovery if those three groups unmentioned by Skidelsky had not been present.

Those of us whom Skidelsky identifies, correctly, as having gotten the big picture right from 2009-present could have won the argument with Alesina and company, Rogoff and company, and Haussman and company. Indeed, we did. Ricardo Haussman now acknowledges the crucial role played by monetary r��gime in the determination of fiscal space. Ken Rogoff recognizes that there is no cliff at which growth falls sharply and discontinuously when the debt to annual GDP ratio exceeds 90%. Alberto Alesina recognizes the necessity of proper support from monetary and exchange rate policy if fiscal contraction is not to be expansionary. We could have won those debates, and won them in a timely fashion. But we could not carry the field when faced not just with our good faith but our bad faith opponents: whether actively purveying misinformation, lazily not thinking, or sulking in their tents like Akhilleus on a bad day, they put enough sand into the gears so that my profession failed to do its job as the memory and planning department of the human race.

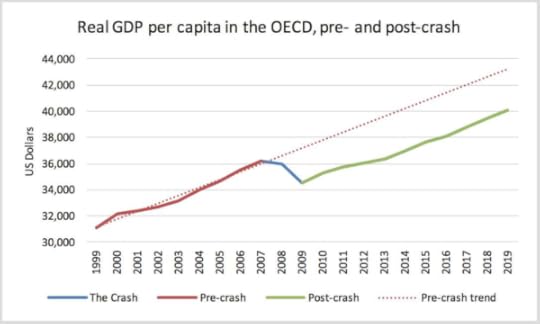

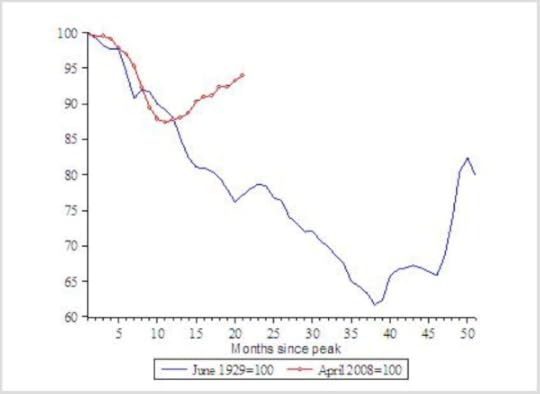

I am kinda surprised they show themselves in polite company: Robert Skidelsky: The Advanced Economies��� Lost Decade: "Policy interventions immediately following the 2008 crash did make a difference.... The 2008 collapse was as steep as that of 1929, but it lasted for a much shorter time...

...The 2008 crisis was met not by belt-tightening, but by globally coordinated monetary and fiscal expansions, particularly on the part of China. As J. Bradford DeLong of the University of California, Berkeley, notes, ���The aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crash was painful, to be sure; but it did not become a repeat of the Great Depression, in terms of falling output and employment.��� Within four quarters, ���green shoots��� of recovery were appearing; that didn���t happen for 13 quarters after the 1929 crash. Yet in 2010... OECD governments rolled back their stimulus policies and introduced austerity policies, or ���fiscal consolidation,��� designed to eliminate deficits and put debt/GDP ratios on a ���declining path���... slowed down the recovery, and probably reduced the advanced economies��� productive capacity as well. In Europe, Stiglitz observed in 2014, the period of austerity had ���been an utter and unmitigated disaster.��� And in the United States, notes DeLong, ���relative performance after the Great Recession [has been] nothing short of appalling.���...

Economists vigorously debated the merits of withdrawing stimulus so early in the recovery. Their arguments, which can be broken down into four identifiable positions, open a window onto the role that macroeconomic theory played in the crisis.

Those in the first camp claimed that fiscal austerity���that is, deficit reduction���would accelerate the recovery in the short run.... Alberto Alesina... much in vogue... assuring European finance ministers that ���Many even sharp reductions of budget deficits have been accompanied and immediately followed by sustained growth rather than recessions even in the very short run.���... Robert J. Shiller countered... ���austerity programs in Europe and elsewhere appear likely to yield disappointing results.���... Jeffrey Frankel pointed out in May 2013 that Alesina���s co-author on two influential papers, Robert Perotti, had recanted, having identified flaws in their methodology. Following more criticism of his methodology by the International Monetary Fund and the OECD, Alesina himself became considerably more circumspect.... Of course, by then, he had already contributed his mite to the sum of human misery....

Those in the second camp countered that austerity would have short-run costs, but argued that it would be worth the long-run benefits.... Out of the Alesina wreckage emerged... ���short-run pain for long-run gain.���... The most influential version of the ���short-run pain for long-run gain��� argument came from Harvard���s Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen M. Reinhart. In their 2009 book, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Rogoff and Reinhart attributed the ���vast range of [financial] crises��� throughout modern history to ���excessive debt accumulation.���... Rogoff claimed that public debt levels above 90% of GDP imposed ���stunning��� cumulative costs on growth. The implication was clear: only by immediately reducing the growth of public debt could advanced economies avoid prolonged malaise.... As Oscar Wilde wrote of Wordsworth, ���He found in stones the sermons he had already hidden there.���... Former British Chancellor George Osborne, who strongly supported reducing the size of the state, credited Reinhart and Rogoff for influencing his thinking....

A third camp, comprising Keynesians, argued unambiguously against austerity.... The Keynesian argument was straightforward. Because the slump had been caused by an increase in private-sector saving, the recovery would have to be driven by government dissaving���deficit spending���to offset the negative impact on aggregate demand. As Mark Blyth of Brown University noted in 2013, the attempt by European governments at the time to increase their savings was having a ruinous effect.... The alternative to austerity���fiscal expansion���would... produce faster economic growth and thus reduce the debt ratio in the medium term.... Fiscal consolidation... reduces the economy���s future productive capacity. When workers experience long-term unemployment... they can fall into a vicious cycle in which they become even less employable with the passage of time. The problem, notes Nouriel Roubini... is that ���if workers remain unemployed for too long, they lose their skills and human capital.���... Hysteresis, which helps to explain the decline in the growth rate shown in Figure 1, can also result from a large-scale switch to inferior employment.... I find the Keynesian perspective more intuitively appealing than the Rogoffian one. It stands to reason that long spells of unemployment or inferior employment will undermine a country���s output potential. But to argue that an ���abnormal��� level of national debt does the same, one must also demonstrate that state spending���whether tax- or bond-financed���hurts long-term growth by reducing the economy���s efficiency. And such a claim relies heavily on ideology....

And the fourth camp maintained that, regardless of whether austerity was right, it was unavoidable, given the situation many countries had created for themselves.... In 2010, the Princeton University historian Harold James pointed out that a country���s creditors can sometimes force it to undergo ���fiscal consolidation.��� This is particularly true for countries with a fixed exchange rate.... In the early years of the crisis, Greece stood out as an awful warning to others. Ricardo Hausmann of Harvard University notes that, ���by 2007, Greece was spending more than 14% of GDP in excess of what it was producing,��� with the gap being ���mostly fiscal and used for consumption, not investment.��� Still, Laura Tyson of the University of California, Berkeley, contends that Europe���s bondholders, led by Germany, conflated Greek public profligacy with private greed and myopia. Expanding on this point, Simon Johnson of MIT observed that while debtor countries suffered dearly for over-borrowing, banks faced almost no penalties for over-lending. Many discussions about the feasibility of different fiscal policies revolve around the mysterious idea of ���fiscal space.���...

In the US, the UK, and the eurozone (after March 2015), economic policymakers sought to offset fiscal contraction with monetary expansion, chiefly by purchasing massive quantities of government bonds. The consensus view is that QE was modestly successful, but fell far short of fulfilling monetary policymakers��� goals. Central bankers had assumed, incorrectly, that if they simply printed money, it would automatically enter the spending stream. This faulty theory of money was driven by pure ideology, as the Nobel laureate economist Robert E. Lucas, Jr., unwittingly intimated in a December 2008 Wall Street Journal commentary. Unlike fiscal expansion, Lucas observed, monetary expansion ���entails no new government enterprises, no government equity in private enterprises, no price fixing or other controls on the operation of individual business, and no government role in the allocation of capital across different activities.��� In his view, these are all ���important virtues������which is to say, a faulty theory is better than one that entails any increased role for the state.�� ��

All told, I believe the policies since the financial crisis have extended the damage of the slump itself. Looking ahead, we will have to confront not just the problem of waste or missed opportunities, but of regression. We are restarting economic life with dimmer long-term prospects than we otherwise would have had...

Should-Read: It would seem... as if he is more focused on...

Should-Read: It would seem... as if he is more focused on how to advance his future lobbying career than in attempting to maintain legislative majorities made up of his friends and those who believe in or at least vote for the policies he approves: Lisa Mascaro and Bill Barrow: Ryan Retirement Fuels House GOP Desperation To Maintain Control: ���'It���s like Eisenhower resigning right before D-Day', said Tom Davis, a former Republican congressman from Virginia...

...���Paul Ryan was the franchise. ith Paul, this was a Republican Party they could still give to. He���s a great brand for the party. He���s gone.���... For Republicans fighting for their political survival, it���s hard not to take Ryan���s decision as vote of no confidence. One Republican in the long list of those already retiring, Rep. Ryan Costello of Pennsylvania, said the speaker didn���t try to walk him off his decision, and in fact seemed to identify with his....

���It���s not confidence building,��� said Ron Nehring, a former party chairman in California....

Ryan dismissed suggestions from some corners, including lawmakers, that maybe it would be best if he stepped aside rather than stick around until January, when the new Congress is seated, as he intends to do. ���My plan is to stay here and run through the tape,��� Ryan told reporters, noting he had ���shattered��� fundraising efforts by previous speakers, more than doubling his $20 million goal. ���I talked to a lot of members���a lot of members���who think it���s in all of our best interest for this leadership team to stay in place���...

Daniel Davies (2002): Evopsych Considered Harmful!: Weekend Reading/Hoisted from the Archives

Weekend Reading: Hoisted from the Archives: Convincing fifteen years ago. Convincing today. Telling just-so stories to reinforce prejudicial hierarchical judgments you won't examine rationally is no way to go through life, son: Daniel Davies (2002): D-squared Digest: "Move over son, the professionals are here... http://blog.danieldavies.com/2002/10/: I've just rediscovered this article by Val Dusek, which is the best thing I've read on the whole debate...

...It also reminded me what a perfect s--- Stephen Pinker looks when you know a little bit of the background to some of the things he says about Margaret Mead. Print out and read on the train home, that's my advice.

UPADATE: God damn that article's good. I'm amazed to discover the extent to which I'd subconsciously plagiarised it. UPDATE AGAIN: Damn me, it's good. I think I'll excerpt a non-representative chunk here, because it sort of buries a point which is, I think, profoundly important:

What Dennett would have to counter is Lewontin and Sober's argument that when selection coefficients of genes are context-dependent and selection acts on gene complexes, the artificially constructed selection coefficients of genes do not play a causal role. (Sober and Lewontin, 1984). It is true that if one claims that what is selected are not genes but replicators as the later Dawkins does, then whole genomes, incorporating all the contextual effects of genes on each other, might be the object of selection. This would preserve the restriction of selection to the genic level, but it would give up the atomization of modular traits with which evolutionary psychologists work.

Massively important, given that now we have the results of the Human Genome Project in, we know that most inherited human behavioural traits will have to have been selected through gene-complexes rather than individual genes. I have not yet seen the EP defence of their core doctrine that traits are modular in the face of this new development; I'd appreciate any pointers to the literature if there are good arguments that the doctrine either can be preserved, or is not actually necessary to the theory.

Tits on a Peacock: Evolutionary Psychology week continues... I'd note in this context that I don't have a complete knock-down argument against evolutionary psychology, mainly because if I did, it would also presumably be a knock-down argument against ethology, which would be damn close to a knock-down argument against evolution. More or less everyone agrees that behaviour can be subject to natural selection, and that's all you need to believe in before you're committed to some sort of belief in some kinds of explanation of psychological phenomena as evolved responses. What I'm most concerned with arguing against is "Neo-Darwinian Sociology", a close cousin of evolutionary psychology, and one which has repeatedly interbred with its less reputable cousin, with predictable results. (Yes I know, I know. That was invective. In actual face, most medical opinion appears to be that the marginal risk of deformed offspring from copulation between first cousins is actually pretty negligible. So go for it if that's what you want, but don't tell the judge I told you to.)

In honest fact, using the phrase "Neo-Darwinian Sociology" is actually an act of extreme politeness on my part, because the more concise phrase would be "Social Darwinism", the age-old and known horrible theory without a shit-eating, disingenuous and self-consciously pious denunciation of which, no pop EP book is complete. (Matt Ridley, I'm looking at you. Daniel Dennet, you can wipe that smile off your face too). It's kind of like the paramilitary wing of evolutionary psychology; the default position of a serious ethologist when confronted with the possibility of earning a quick two hundred quid for 400 words on some current issue in the Sunday papers (Richard Dawkins, I'm looking at you, and pointing at you). Basically, in so far as these pieces have any message which doesn't consist of laughing at people more intelligent than the author for believing in God, the message boils down to:

Psychology of individuals is sociology; there is nothing to be understood about social phenomena other than individual behaviour. (The main argument for this proposition is that sociology is carried out by sociologists. The secondary argument is that some sociologists vote for left-wing political parties. Don't ask me, I'm only here for the beer)

Genetic explanations are the most important kind of explanations. If something could have come about through sexual selection of a gene, then it is overwhelmingly likely did come about in that way. Any other kind of explanation is very much second-best, and is probably about to be proved false by the discovery of a "proper" explanation. (The argument for this is rarely spelt out; as far as I can tell, it is some degenerate version of Occam's Razor)

Although just-so stories about hypothesised past development are no more than indicative initial hypotheses when we're doing proper rigorous ethology, they're strong enough that you can draw massive overarching social policy conclusions from them when you're talking to the plebs. (There is no argument for this at all, but I'm guessing it's part of the organisational pathology which gets these things into print)

Push them on any of these points, however, and they immediately retreat to vastly more defensible ground, only talking about specific results, qualifying all their statements and pretending that their sentences should never be (could never possibly have been) taken to imply things which they quite obviously say. Of course, given that we're dealing with Dawkins, Pinker, and arseholes of similar magnitude here, they tend to carry out this retreat with the full pomp and circumstance of a Roman triumphal parade, insulting people's intelligence, taking every opportunity to revive assertions they've walked away from and if at all possible, trying to imply that their interlocutor is either a sociologist or a believer in God. I see that it will take a separate post on the roots of this behaviour in philosophy of science to drain away all my bitterness.

But anyway, that's "Neo-Darwinian Sociology", and I actually believe that I do have a knock-down argument against that, which I will outline in the next-but-one post in this series. For the time being, just note that I think I can support the claims that

if it wasn't for their occasional forays into N-DS, the EP crowd would be a very obscure bunch of scientists indeed.

NeoDarwinian Sociology is on a much weaker scientific footing than the rest of EP; those parts of EP which have impinged on the public consciousness are in general pieces of research which are distinctly suspect as works of science; and therefore :

The entire existence of evolutionary psychology as a fact of public life rather than an obscure academic discipline depends on the willingness of some scientists to drop all their scientific standards at crucial moments. (In particular, I find it quite scandalous that Richard Dawkins is quite so unconcerned about the distortions of scientific method which are regularly indulged in by people he regards as his allies. Despite what he thinks, he is Oxford University's Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science, not the Public Proselytisation of Atheism). I am also prepared to argue for:

The fact that it's the evolutionary psychologists who have achieved such prominence through such means is, as they say, no coincidence; the entire method of inquiry of EP tends to inculcate habits of mind which are too quick to latch onto hypotheses and call them explanations, and which discourage rigorous system thinking in favour of particular anecdotes. In their professional work, practitioners seem to recognise these dangers and guard against them; in their popular work and their policy advocacy, they drop their guard. As you can tell, I'm working toward a theory of how a book as bad as "Blank Slates" by Stephen Pinker came to be written.

It's in support of (4) that I am currently working. As with yesterday's post on symmetry and beauty, I want to provide an example not so much of questions answered wrongly, but of questions never asked in the first place; of theories adopted for a particular case because of the attractive story, but which were not applied to other cases, because they didn't fit the story being told. If I can establish that there are cases when, working near the borders of ethology and sociology but on the scientific side, evolutionary psychologists lost their critical faculties, I think I'll have supported my case that when they move closer to politics, they tend to be even worse. Tomorrow's example is going to be just a freaking doozy (Randy Thornhill's theory of rape), but for the time being, let's take a look at womens' breasts and peacocks' tails.

OK, I didn't get many takers for peacocks' tails. But let's start off with them.

There's a fairly common theory about why peacocks have tails; it's not the only one in the literature, but's it's pretty well supported and it is frequently used by the EP crowd when they want to make an analogy to certain kinds of male behaviour. The theory is basically, that the male peacock's tail is so big not in spite of its inconvenience to the bird, but because of that inconvenience. The idea is that it's a sexual signalling device; the peacock is signalling:

Look at me, I'm so big and strong and genetically ace that I can carry around this huge great fucking ridiculous tail and still live a relatively normal avian life.

So, the selfish genes of the peahen latch onto that signal, because they want to hitch a ride on this unstoppable Range Rover of peacock genetic goodness. It's quite a clever little theory; controversial as hell among bird biologists, but certainly not without supporters.

So anyway, a theory like that is too good to waste on peacocks, so it gets brought into service in explaining otherwise damnably stupid behaviour by human males with "peacock" tendencies. Bungee jumping, driving cars quickly, etc, etc. Jared Diamond (in an uncharacteristic slip; a terrible chapter of an otherwise good book called The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee) claimed that kung fu experts in Indonesia drink paraffin. The idea being presumably, to show off to any females present "HEY, LOOK AT ME! I'M ACTING LIKE AN IDIOT! I MUST HAVE GREAT GENES TO HAVE SURVIVED TO ADULTHOOD, I'M SO FUCKING STUPID! IT'S A MIRACLE I'M NOT EATING THROUGH A STRAW, BUT I'M NOT, SO THERE MUST BE SOMETHING SPECIAL ABOUT ME! COME ON AND GET ME YOU KNOW YOU WANT IT!".

Obviously, the questions a) "has there ever really been an 'evolutionary adaptive environment' in which purposefully endangering your own life for no reason hasn't been a gene that sensible selfish maximisers would want to avoid like the plague?" and b) "does it not strike people who advance this 'hazard theory' as perhaps surprising that much of the very most stupid and show-offish male behaviour in the world is channelled into initiation rituals of exclusively male secret societies of one kind or another?" are quibbles, and prove that the person asking them is a sociologist, and probably believes in God.

Anyway, I sense that my audience is getting bored at this point, so on to the more popular topic of womens' breasts.

As everyone knows, men like women with big, prominent breasts because they indicate that the woman upon whom they are located will be really good at feeding a child, thus propagating their genes to the next generation. Unfortunately, the bust size of a woman who has never given birth bears more or less no relationship whatever to the size at the end of pregnancy (breasts of nonlactating women are made mostly of fat, and it takes about eight months to properly shape them up to serve drinks), and this has been the case for a very long time in human evolution. This immediately rules out a lot of the "sub-pop" science commentators who use this kind of cargo-cult science theory of female pulchritude when they want to make some sort of point about sexual harassment in the workplace or the appeal of Pamela Anderson or whatever needs half a col. written about it by two-thirty prompt, but that's hardly a body blow to the EP crowd; most of these people are either editorial writers half-remembering the last pop science book they read, or people like Eric Raymond who are so damnably ignorant on every single subject except computers that it can't be blamed purely on "The Selfish Gene".

On the other hand, there are a lot of commentators who know better, who still basically come up with theories of the breast which involve some sort of signalling about fertility (not all; here's a list of theories on this issue, not all of which are vulnerable to the current critique). And here, we come to a conundrum.

If the theory of doing dangerous things in order to show how genetically fit you are is generally applicable, perhaps it could be applied to women as well as men? So, let's think... what would be an extremely physically demanding and dangerous thing that a woman could do, which would work well to demonstrate her fertility? Well... perhaps it's a bit off-the-wall, but here's one suggestion... how about... giving birth to a baby?!

Think about it. Some women are infertile, and can never give birth. Some women are not physically up to the rigours of childbirth, and this must have been even more true "out on the plains of Africa", to use the hackneyed and racially loaded catchphrase. One way, as a woman, of proving that this isn't true of you, is to actually step up to the plate and walk the talk. So, on this reasoning, men should be really turned on by single mothers... is that your experience?

Furthermore, if we extend this theory to go back to our original question about fashions in bust shapes, we can note that the stresses and strains of feeding the first child will certainly, pre the invention of the brassiere, have taken their toll on a maidenly chest. So, one could construct a convincing argument on evolutionary psychology grounds, that a female human equivalent to the display of the peacock's tail would be a large bust which drooped to somewhere south of the navel area. By putting on the Gossard Wonderbra and its competitor products, women appear to be attempting to signal to men that their fertility is a completely unknown property, and so is their vulnerability to death in parturition.

There is something decidedly funny about a grab-bag of intellectual tools which puports to explain the reason why things are the way they are, but which could simultaneously be used (as above) to explain why they were the way they were even if they were some other way. And there is something funny about a group of people who talk nine yards to Sunday week about the "intellectual rigour" they are bringing to a discipline like sociology, but who never seem to bother to generalise propositions, or to explain why mechanisms work in one case but not another. And there is something extremely funny about the way that a bunch of male commentators have been so quick to jump on board with a theory that, if it were not for the fact that it helps to bolster a number of propositions about sexual morality which they wanted to assert anyway, would be recognised as being about as likely and as useful, as tits on a peacock.

Thy Bloody Awful Symmetry: As well as the whole Michael Hardt/ David Hasselhoff thing below, my mind was turned to thoughts of evolutionary psychology by an article in yesterday's New York Times.

Fundamentally, it's exactly the sort of work I was planning on doing; somebody's taking a look at the actual experimental methodology that supports such convenient factoids as "men are more concerned about sexual jealousy, while women worry more about emotional infidelity". It turns out that this "result" is incredibly fragile as to the situation of the experiment; if you sit people down, ask them the question straight out, and give them time to think, then men and women assign themselves correctly to their gender roles, whereas if you catch them off guard in order to get a more "instinctive" response, the differentiation "predicted" by an amazingly tendentious just-so story about cavemen in Africa just doesn't show up. (I'd note in passing that the EP crowd are often in the forefront of moaning about "double-blind trials" when they're on the attack on some other point; the methodology of having an experimenter with an agenda ask a question face to face and then write the answer down himself is about as far from double blind as it gets).

In any case, the main point of the article linked above is to show what total and utter patronising knobheads evolutionary psychologists can be when pulled up on a point of science (read it, honestly, the guy starts comparing himself to Galileo!). But it dovetails quite nicely with a couple of points I'd like to make about some other sacred cows of evolutionary psychology; specifically, some of those claims which the pop science gang like to make about the "genetic" foundations of human beauty.

It's a shame that I'm too mean to cough up for the version of this weblog which would allow me to put up pictures, but there you go... but you don't have to search far on the web to find someone claiming it to be an established "fact" that facial attractiveness is a function of facial symmetry. Coincidentally, you also don't have to go far on the web to find a picture of Elvis Presley (bloody great asymmetric sneer) or Cindy Crawford (bloody great asymmetric mole on face). So what gives?

Apparently people with symmetric bodies have "good genes". Don't ask me, I'm a stranger here myself. But let's assume for the meantime that in some way, a little glitch in the building of the face of a foetus is evidence of a deep-seated horrible lurgey in the genes which is just waiting to show up as sickle-cell anaemia or low resistance to malaria or something. The question I'm interested in is, how did anyone find out that people with symmetrical faces are the most beautiful people of all?

Note at this stage, that I'm not interested in studies which claim to have shown that symmetrical people have more sex than anyone else. Randy Thornhill claims that this is the case, and it might be the case even though the experiments which claim to demonstrate it come from the same guy who brought you a theory of rape which doesn't work at all as a theory of sexual assault not involving penetration. Personally, I think that Thornhill is all over the place, and I'll explain why in future (there's a clue in this sentence for the impatient), but I want to establish that it doesn't effect my current argument if the symmetrical are shagging wild all over the place. The claim that "beauty" is "whatever gets you laid" is one that the EP crowd is committed to, not me. But this is by the by.

Absent the sex life studies, the evidence for "beauty" being this, that, or the other, has to come from what actual people judge to be beautiful. So, the best method for carrying out this experiment would have to be to get a bunch of people, show them a bunch of photographs of people, and get them to pick out the beautiful ones. Then you count the number of points each photograph gets and have a look at which ones are picked the most often, right?

Wrong.

If you ask people to pick out the photographs from a set which strike them as the most beautiful, you're actually asking them to perform cognitive acts, not one. You're asking your experimental subjects to:

notice a picture of a face

judge whether it's beautiful or not.

The first of these is not a trivial act, as anyone who's observed a baby younger than about two months will testify. The extent to which you're going to carry out the act of picking a picture for the beautiful pile depends on the extent to which it catches your attention as well as what you actually think of the face. There will be an error in your results from people "misclassifying" faces because they weren't really paying attention to them. There are all sorts of misjudgements that it's possible to make when looking at a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional object; as the post below demonstrates, I quite seriously misclassified a picture of Michael Hardt's hairstyle as "bouffant" when it wasn't.

So far so good. Now, readers with extremely advanced degrees in econometrics won't be asking... what do we know about this error? Importantly, is it unbiased���can we assume for modelling purposes that it can be ignored as something that will in a large enough sample?

I'm arguing, no. One of the things that, broadly construed, evolutionary psychology has usefully done for us is to dig up some important insights into the neuropsychology of visual perception. Particularly, it's been noted (as in, anatomically observed) that there is a mechanism in the brain which is specifically adapted for distinguishing between symmetrical things and non-symmetrical things. I find the "evolutionary psychology" (in actual fact, ethology, the rather more serious parent discipline which looks at behaviour without making tendentious and unsupported claims) argument quite convincing in this regard. The reason we have a symmetry-detector is that very few things in nature are symmetrical except animals, and animals are only symmetric when they're looking straight at you. Since the fact that something is looking at you is almost always a useful thing to know, we have been provided with a very acute sense of whether a thing is exactly symmetrical or not. Symmetry is a property which "jumps out of the page".

So, given that photographs of symmetrical faces are more likely to be noticed, the errors are not going to be evenly distributed. In any study which is asking you to pick out a "noticeable" characteristic the symmetrical pictures are always going to be over-represented, because symmetry is a noticeable property. Furthermore, this property is highly likely to account for the fact that babies tend to look longer at the same photos which adults pick out of a pile as being most attractive, another factoid often advanced as evidence for the beauty=symmetry hypothesis.

I have no particular investment in believing that there is nothing aesthetically attractive about symmetry; I spend a lot of time with a sneer on my face, but that's mainly because I read a lot of right-wing weblogs. But the fact that nobody saw fit to inquire into this possible source of experimental failure tends to suggest to me that people want to believe in the "evolutionary" arguments for reasons other than those of pure science. And when you get people like Todd Shackelford responding to the Northeastern study by just saying "I guess, to state it plainly, I think the paper is in large part ludicrous.... It's clear to me that they have an agenda they're pushing", I think I'm on to something...

April 12, 2018

I Look at How Bad Professional Republicans Calling Themselves Economists Are Today, and...

A friendly correspondent points out to me that the "serious and respected" professional Republican economists of 20 years ago were as big bull-------- as those today���and that I was complaining about them, albeit attempting to be more polite, back then.

Case in point: Allan Meltzer: Hoisted from the Archives from Twenty Years Ago: Allan Meltzer Drags Down the Level of the Debate...: He attracted my ire for going beyond a line he should not have gone beyond:

Consider the following, a critique of a line of work on "Equipment Investment and Economic Growth" that I have been pursuing with Larry Summers:

...Professor Lawrence Summers and Bradford DeLong claim to have evidence that investments in machinery produce returns to society far beyond the returns to investors.... The state, however, can supplement private investments, or subsidize them, and capture the returns for society.... Alas, it isn't so. Subsequent research showed that Summers and DeLong were misled by the presence of Botswana in their data set. During the sample period they used, Botswana invested heavily in mining machinery to exploit its diamond mines. Botswana had the highest growth rate and the largest share of spending on equipment investment, so machinery investment and growth appeared to be strongly related. Excluding Botswana, one of sixty countries, showed the results to be spurious...

Now take a look at a selection from the very first thing we wrote about equipment investment and economic growth, taken from the section, "Sample Selection Issues", where we discussed which observations should and should not be in our data set:

Results using the entire 61-nation sample are somewhat sensitive to outliers. The exclusion of Zambia, for example, raises the adjusted R2 in the regression underlying Figure VI from 0.29 to 0.44; the exclusion of Botswana would reduce the adjusted R2 from 0.29 to 0.21. Inclusion or exclusion of these two countries can move the equipment share coefficient between 0.21 and 0.31, although the coefficient remains significant at conventional levels.

....[I]t is worth pointing out that [the large 61-nation sample] omits two outlier nations with large identifying variances that would significantly strengthen our findings. Both Singapore and Taiwan have had high equpment quantities, low equipment prices, and rapid productivity growth in the post-World War II period. Neither Singapore nor Taiwan is in our sample.... The inclusion of these two observations would strengthen our conclusions.

Let's run, backwards, through what Meltzer said:

Claim: "Excluding Botswana... showed the results to be spurious"

Truth: Whether Botswana was left in or taken out of the sample, the results still held: "remain[ed] significant at conventional levels"

Claim: "Summers and DeLong were misled by the presence of Botswana in their data set."

Truth: As we wrote in our very first paper on "Equipment Investment and Economic Growth", the surprisingly strong association between equipment investment and economic growth is there--whether Botswana and other low-income outliers are included in or excluded from the data set.

Claim: "Subsequent research showed..."

Truth: We were the ones who flagged the effect on our statistical study of the inclusion in our sample of Botswana (and of Zambia, and of Tanzania, which work in the other direction; and the omission of Singapore, and of Taiwan, which also work in the other direction) as important issues.

The implication that we did not understand what was going on in our dataset until "subsequent research" pointed it out to us is wholly false.

In the long run it will become clear whether countries with high rates of machinery investment grow rapidly because the social returns to investment in machinery and equipment are astronomically high, or because of some one of the other factors Larry Summers and I discussed in our articles: perhaps machinery investment is high in fast-growing countries because investors forecast fast growth and high profits, and channel investment into such countries; perhaps machinery investment is high in fast-growing countries because savings are high whenever income is growing rapidly, and savings have to be used for something; perhaps machinery investment is high in fast-growing countries because governments that make investment profitable are taking many other steps--educating the population, controlling corruption, reforming the tax system--that promote growth.

I think that the preponderance of the evidence is that machinery investment does have very high social returns, but I agree that the case is not conclusive.

But I think much more strongly that comments like Allan Meltzer's���which he could not have been written if he had done his homework and actually read our article���poison the well of economic debate.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers