J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2189

September 30, 2010

Henry Farrell Continues His War on Rubber Tomatoes...

Henry Farrell:

How Do You Like Those Tomatoes? — Crooked Timber: Tim Lee takes exception to my post of a couple of weeks ago on James Scott and Friedrich von Hayek, suggesting that I construct a ‘curious straw-man’ of Hayek’s views. Unfortunately, he completely misreads the post in question. Nor – on serious investigation – do his own claims actually stand up.... This is not a dispute about whether planning is to be done or not. It is a dispute as to whether planning is to be done centrally, by one authority for the whole economic system, or is to be divided among many individuals. Planning in the specific sense in which the term is used in contemporary controversy necessarily means central planning--direction of the whole economic system according to one unified plan. Competition, on the other hand, means decentralized planning by many separate persons. The halfway house between the two, about which many people talk but which few like when they see it, is the delegation of planning to organized industries, or, in other words, monopoly....

Hayek is claiming that markets are superior to planning (which must necessarily be done through a single centralized planner) or organized monopoly (which no-one actually likes). One could perhaps defend Hayek by arguing that there were indeed many people who argued for centralized planning at the time he wrote this essay. But one would then have to contend with the notorious contortions he got into about how Labour’s efforts to introduce planning into the economy would ineluctably lead to totalitarianism. The straw man is baked into the theoretical cake (which as a result tastes pretty godawful)....

When Scott says:

It seems to me that large-scale exchange and trade in any commodities at all require a certain level of standardization.

and later refers to Polanyi’s The Great Transformation as ‘the most important book I’ve ever read.’ he seems to me to be building on Polanyi’s crucial distinction between small scale and large scale markets. Roughly speaking, Polanyi sees local markets as fine, because they are ‘embedded’ in society, and hence do not threaten it. But when long distance trade first becomes unmoored from societies, and then to restructure them along its own principles of order, we start to get into trouble.

Scott’s specific twist on Polanyi’s thought is to identify standardization as a key facet of this unmooring. Local markets are embedded in local structures of knowledge, and rely upon them extensively – people know that Giovanni’s tomatoes usually taste better than Luigi’s, even if they are less regular and have more surface blemishes. International markets require technical standards – in order to buy and sell tomatoes, one has to be able to categorize them as Grade II (with certain defined attributes in terms of color, size, consistency etc), Grade III etc. Scott argues that there is a real and fundamental loss of knowledge that occurs in the standardization process, regardless of whether the standards are imposed by states are by markets. Indeed, he sees the two as going hand-in-hand. Brad DeLong (like Lee) made much of Scott’s critique of the state, but failed to observe how intricately this was linked to a critique of the market....

Hence – when Lee suggests that:

Although Scott specifically declines to endorse Hayek’s policy agenda, I think Seeing Like a State is squarely within the Hayekian intellectual tradition.

he is simply wrong, unless (contrary to what Lee and I both believe), Hayek has written somewhere within his voluminous opus on the problematic tradeoffs that markets face when they become unmoored from local society. This distinction is, I am pretty sure, an inherent part of Scott’s intellectual project.

Lee makes a positive Hayekian case on behalf of standards – this too, it seems to me, is wrong.... The key problem is in his (again standard Hayekian) defense of the processes through which certain rules come to dominate. What makes decentralized economic institutions powerful isn’t standardization but the possibility for competition among alternative standardization schemes. Rubber tomatoes create an entrepreneurial opportunity for firms to establish a more exacting tomato standard and deliver tastier tomatoes to their customers. In real markets, you see competition not only among individual firms but among groups of firms using alternative standards. Markets gradually converge on the standards that are best at transmitting relevant information and discarding irrelevant information. In contrast, when standards are set by the state, or by private firms who have been granted de facto standard-setting authority by government regulations, there is no opportunity for this kind of decentralized experimentation. The problem with this claim is that it relies (as Hayek relies) on quite heroic assumptions about the underlying conditions under which competition occurs.... Perhaps the very particular standards that Lee points to are different. He claims:

The web browsers we all used to retrieve this article conform to a variety of technical standards, including TCP/IP, HTTP, and HTML. … This suite of now-dominant protocols emerged from an intense process of inter-standard competition during the 1980s and 1990s. This competitive standardization process is not a market process—accessing a web page is not a financial transaction—but it is very much a Hayekian one.

Or again, perhaps not, if notorious libertarian-hater Dan Drezner is to be believed. In a detailed study of the adoption of TCP/IP, Drezner finds that state power was the key factor determining which standard won out.... But perhaps, in the absence of government power, we might expect Lee’s arguments to work? Almost certainly not. Hayek-style evolutionary arguments really only work when actors are indifferent between coordination outcomes (i.e. they want to coordinate, but do not care what outcome they coordinate upon).... This applies in spades to Lee’s other example of Hayek in action – the HTML standard. Anyone who has had to optimize web sites for various browsers will be familiar with the fact that different browsers have different ways of interpreting what is purportedly the same standard. And anyone who bothers to look into the politics behind this will be quite aware that Microsoft’s infamous policy of ‘embrace, extend, extinguish’ plays a significant role in this story. Microsoft Word’s .doc standard is an even purer example of how standard-setting processes play out in markets where businesses are competing to set the rules of the game. And if anyone wants to argue that Microsoft Word was an efficient outcome of a competitive process, all I can do is post this image and say: Sir. I refute you thus.

In short then: (1) Lee completely misreads my post. (2) James Scott is not a Hayekian under any reasonable definition of the term Hayekian. (3) Hayekian arguments about evolutionary competition both are implausible in general, and provide a demonstrably bad explanation of how technical standards evolve. (4) And, finally, rubber tomatoes suck. I think that covers everything.

I, by contrast, say that you have to either live in the countryside or live in the city and be really rich to say that rubber tomatoes suck. For those humans who live in the city and are not really rich, rubber tomatoes provide a welcome and tasty and affordable simulacrum of the tomato-eating experience.

When Artificial Intelligence Programs Attack!

GMail gets above itself:

No. I would be happy to email Jeffrey Greenbaum. But this message is not intended for him.

Just because Jeffrey is often a recipient on emails I send to Barry and Christina does not mean that I don't want to email my department chairman...

Obama Personnel Non-Policy: Jonathan Bernstein Pulls His Punches...

He writes:

A plain blog about politics: Two For the Fed: I've mostly thought that Rahm Emanuel has done a good job in many respects, but the appointment process is definitely not one of them, and Obama should keep that in mind when he's putting his new team together.

That won't do it. That doesn't describe the situation. And as I have eaten my wheaties and read Michael Foucault's final Berkeley lectures about parrhesia, I am going to say what needs to be said.

First, a longer quote from Jonathan:

The Senate apparently cut a deal yesterday, approving a long list of executive branch nominations, most notably Janet Yellen and Sarah Raskin to the Fed (but not the third Obama nominee, Peter Diamond). Presumably in exchange for that, and for GOP co-operation on some technical stuff that would have been a (minor, I think) hassle for the Democrats during the lame duck session, Harry Reid agreed to hold pro forma sessions through October so that Barack Obama cannot do any recess appointments. Brad DeLong's reaction is that "we need a very different Senate." It's certainly fair to criticize the Senate for taking forever to confirm nominations that are not controversial -- the Fed appointments were approved by voice vote, and the other 52 nominations were by unanimous consent.... The nominations were announced on April 29 of this year, so it took the Senate five months. That's not great...

[B]ut if I recall correctly, two of the openings here go back to the beginning of Obama's presidency... far more of the delay is the responsibility of the president, not the Senate. Moreover, by taking so long to nominate people for executive and judicial positions, the White House is sending a signal about priorities.... Now, granted, part of the reason that nominations are taking so long in the first place is presumably because of how hard they are to confirm.... Still, I put a lot of the blame here on the administration...

To this I have two things to say:

Blame is not zero-sum. Jonathan Implies that the blame should be taken off of the Senate and placed on... Rahm Emmanuel. No. It doesn't work that way. Both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue are blameworthy, and should be blamed.

The COSSACK WORKS FOR THE CZAR!! THE APPOINTMENTS %^$#@$% SCREW-UPS IN THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION ARE NOT RAHM EMMANUEL'S FAULT BUT BARACK OBAMA'S. In a sane system of government--a parliamentary system, for example--Obama's failure to take appointments seriously would be proper grounds for his immediate elevation to the House of Lords and exclusion from any and all levers of power. Nobody should accept a senior appointment to the cabinet or the White House staff until Obama names somebody else as Deputy President for Personnel--Chris Edley or Erskine Bowles or John Podesta or whoever--and agrees to rubber-stamp their decisions. If Obama isn't interested in that part of the job, fine: he shouldn't do it. But he needs to let somebody else do it--and do it now, and blaming Rahm for this is not accurate.

Austan Goolsbee on the Tax Cut Fight

What Is This "Demand for Money" of Which You Speak?

If our big macroeconomic problem of deficient demand for currently-produced goods and services were the result of a deficient supply of liquid cash money--the stuff you keep in your pockets and use for clearing and functions as a medium of exchange--then the prices of all alternatives to money would be very low: people would be trying to dump their holdings of other assets to build up their stocks of liquid cash money, and only very low prices of and very high expected rates of return on those alternatives could check that desire. Thus we would expect a downturn caused by a shortage of liquid cash money to be accompanied by very high interest rates on, say, government bonds--which share the safety characteristics of money and serve also as savings vehicles to carry purchasing power forward into the future, but which are not liquid cash media of exchange.

Nevertheless, David Beckworth writes:

Macro and Other Market Musings: Martin Wolf, the Paradox of Thrift, and the Excess Demand for Money: Martin Wolf concludes more borrowing may be just what the economy currently needs.... [His] paradox of thrift idea is really nothing more than another way of saying there is a monetary disequilibrium created by an excess demand for money. And, of course, an excess demand for money is best solved by increasing the quantity of money. The painful alternative is to let the excess money demand lead to a decline in total current dollar spending and deflation until money demand equals money supply... the paradox of thrift requires the Fed to be asleep on the job.

Let me explain why the Paradox of Thrift is really just an excess demand for money problem.... [I]ndividual households can save... by cutting back on consumer spending and hoarding money... by spending income on stocks, bonds, or real estate and... by paying down debt.... [I]ncreas[ing] their holdings of money by cutting back on expenditures... will create an excess demand for it and a painful adjustment process will occur. If, on the other hand, the Fed adjusts the money supply to match the increased money demand then the painful adjustment is avoided.... In the latter two cases where assets are bought and debt is paid down the money is passed on to the seller of the assets or to the creditor. Here, the only way to generate the painful adjustment is for the seller or creditor--or any other party down the money exchange line--to hoard the money. If the creditor or seller does not hoard the money then it continues to support spending and price stability. All is well. Increased austerity, then, only becomes an economy-wide problem when it leads to an excess demand for money.... The fundamental proposition of monetary theory is that an individual household can adjust its money stock to the amount demanded, but the economy as a whole cannot...

The hole in David's argument is, I think, where he says "the Fed adjusts the money supply" without saying how. Suppose that we have a situation--like we have today--where people are trying to cut back on their expenditure on currently-produced goods and services in order to build up their stocks of safe assets: places where they can park their wealth and be confident it will not melt away when their back is turned. They switch spending away from currently-produced goods and services and try to build up their stocks of safe assets--extremely senior and well-collateralized private bonds, government securities, and liquid cash money. Now suppose that the Federal Reserve increases the money supply by buying government securities for cash. It has altered the supply of money, yes. But it interest rates are already very low on short-term government paper--if the value of money comes not from its liquidity but from its safety--then households and businesses will still feel themselves short of safe assets and still cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services and the expansion of the money supply will have no effect on anything. The rise in the money stock will be offset by a fall in velocity. The transactions-fueling balances of the economy will not change because the extra money created by the Federal Reserve will be sopped up by an additional precautionary demand for money induced by the fall in the stock of the other safe assets that households and businesses wanted to hold.

So, yes, Beckworth is right in saying that there is an excess demand for money. But he is wrong in saying that the Federal Reserve can resolve it easily by merely "adjust[ing] the money supply. The problem is that--when the underlying problem is that the full-employment planned demand for safe assets is greater than the supply--each increase in the money supply created by open-market operations is offset by an equal increase in money demand as people who used to hold government bonds as their safe assets find that they have been taken away and increase their demand for liquid cash money to hold as a safe asset instead.

Increasing the money supply can help--but only if the Federal Reserve does it without its policies keeping the supply of safe assets constant. Print up some extra cash and have the government spend it. Drop extra cash from helicopters. Have the government spend and. by borrowing to finance it, create additional safe assets in the form of additional government debt. Guarantee private bonds and make them safe. Conduct open market operations not in short-term safe Treasuries but in other, risky assets and so have your open market operations not hold the economy's stock of safe assets constant but increase it instead.

These are all ways of increasing the money supply or of decreasing the effective demand for money by shifting some of the precautionary demand for money-not-as-liquid-but-as-safe-asset over to newly-created other safe assets.

These are all ways that ought to work, the Lord willing and the creek don't rise.

But to say that the problem is an excess demand for money is, I think, misleading, for it suggests that the standard way of increasing the money stock--open market operations that swap liquid cash for other assets while holding the total stock of safe assets in the economy constant--will also work. And by this point I think we have a bunch of evidence that it does not.

And to describe these other policy moves--printing up some extra cash and having the government spend it; dropping extra cash from helicopters; having the government spend and. by borrowing to finance it, create additional safe assets in the form of additional government debt; guaranteeing private bonds and making them safe; conducting open market operations not in short-term safe Treasuries but in other, risky assets and so having your open market operations not hold the economy's stock of safe assets constant but increase it instead--as "monetary policy" seems likely to me to add to the general confusion. When the excess demand for liquid cash money is itself the result of a spillover from a more fundamental excess of (planned) savings over investment or of (planned) safe asset holdings over supply, standard open market operations that are designed to hold the stock of safe assets and the stock of savings vehicles constant are unlikely to work. And when Federal Reserve monetary expansions do work, it is likely to be because they not only increased the supply of money but more important increased the supply of safe assets or increased the supply of savings vehicles.

The point, I think, is that liquid cash money is not only a medium of exchange but it is also a store of value--a savings vehicle--and a hedge--a place of safety that you hold in your portfolio to satisfy your precautionary demand, and so the transactions demand for money is only part of the whole. But because other assets are stores of value and hedges a well, to focus exclusively on the supply and demand for money is to miss much of the action in times like these.

I am still frustrated that all of this seems so clear to me and is to opaque to so many other smart people. Personally, I blame Olivier Blanchard for making us spend three weeks on Lloyd Metzler's "Wealth, Saving, and the Rate of Interest" in my first year of graduate school...

UPDATE: Nick Rowe comments on David Beckworth:

Yes! There is no paradox of thrift. There is a paradox of hoarding the medium of exchange. That's because there are two ways to buy more money: sell more other things; buy less other things. One of those two options is always open to the individual, but not to everyone.

The only case where Say's Law is wrong is when there is an excess demand (or supply) of money, the medium of exchange.

Could I make Nick Rowe happy by saying that there is too a "paradox of thrift," in this sense:

When there is an excess of (planned) savings over investment, savers will be unable to find enough bonds to satisfy their demand and will park the excess demand in liquid cash money instead, which they will hoard. They will thus diminish the supply of money available to meet the transactions demand for money and that imbalance creates the excess demand that breaks Say's Law. Thus even though the problem as an excess demand for money, standard open-market operations will not resolve it: they will increase the money supply, yes, but by diminishing the supply of other savings vehicles they will also increase the amount of the money stock not available for transactions purposes because it is being held as a savings (or a safety) vehicle

?

Does that make anything clear, or just deepen the darkness?

Yes, a Lot of Our Current Unemployment Is Cyclical, and Would Melt Away If Demand Were Higher...

Mark Whitehouse:

Employers Aren’t Trying Hard to Hire: Steven Davis of Chicago Booth School of Business, R. Jason Faberman of the Philadelphia Fed and John Haltiwanger of the University of Maryland — take a deep dive into Labor Department data and come up with an estimate of what they call “recruiting intensity,” a measure of employers’ vacancy-filling efforts including advertising, screening and wage offers. Their finding: Employers haven’t been trying as hard as they usually do. Estimates provided by Mr. Davis suggest that over the three months ending July, recruiting intensity was about 12% below the average for the seven years leading up to the recession. Their lack of effort probably accounts for about a quarter of the shortfall in the hiring rate.

In Which Matthew Yglesias Observes That Innumeracy Is an Awful Thing...

Chris Bertram writes:

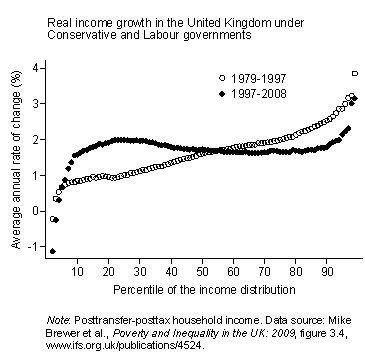

New Labour and Inequality: Blair, Mandelson, Milburn and the rest of the gang not only failed to achieve Labour’s goals concerning inequality and social justice, they abandoned them, an abandonment summed up in Mandelson’s notorious statement that he was “intensely relaxed” about people at the top becoming “fithy rich”. New Labour, taking their cue from the Clinton Democrats, abandoned the distributive objectives of the left on the basis that the rising prosperity engendered by growth, markets and globalisation would benefit everyone. Well it hasn’t. Personally I think it was never going to, for “spirit-level” type reasons, among others. But anyway, that model ran into the wall of the banking crisis and we’ll shortly see the absolute standard of living of the poorest falling as the deficit gets clawed back at their expense.

And Matthew Yglesias wonders why Chris Bertram cannot add:

I’m always blown away by the level of righteous indignation that British lefties are able to muster about the economic record of the Blair/Brown “New Labour” governments.... [H]ere’s Lane Kenworthy’s chart of income growth by decile.... New Labour had these (presumably finance-driven) gains at the tippy-top but also major progress for the bottom half... [I]t’s quite true that Cameron/Clegg austerity is likely to lead to bad outcomes for the poor, but it’s odd to say that New Labour cardinal sin was that it could “only” stay in power for 12 years.

If anything that point strengthens the case that voting Labour—even New Labour—is crucial to the interests of the British working class....

[I]f anyone has just cause to complain about the New Labour record it’s educated professionals up there in the 70th to 90th percentiles who did better under Thatcher even as they’ve had to watch their classmates move on to riches in finance.

September 29, 2010

Finally...

At least one year late and many dollars short:

Nominations Confirmed: September 29: These nominees were confirmed by Voice Vote:

Sarah Bloom Raskin, of Maryland, to be a Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System for the unexpired term of fourteen years from February 1, 2002

Janet L. Yellen, of California, to be a Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System for a term of fourteen years from February 1, 2010

Janet L. Yellen, of California, to be Vice Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System for a term of four years

We need a very different senate.

links for 2010-09-29

Riksbank's Svensson Warns Against Rate Rises Amid Housing Boom - Bloomberg

The European crisis gets quietly worse | Analysis & Opinion |

Why liberals will be glad to see Rahm Emanuel go. - By David Weigel - Slate Magazine

Sean Carroll: Aristotle on Household Robots

Today's Additions to the Pile...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers