J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2158

November 12, 2010

The Very Disappointing Derek Thompson Reaction to Liberal Criticism of Simpson-Bowles

It was disappointing.

The worst and most unfair part, I thought, was this slam against Kevin Drum:

The Disappointing Liberal Reaction to the Deficit Commission: The third most frustrating criticism comes from folks like Kevin Drum, who claims that any effort to reduce the deficit that isn't 98% health care reform isn't serious. The fact is, there are no feasible ways to definitively curb health care inflation starting today (if Kevin has some in mind we need to hear them!). We can shoot a thousand arrows at the medical inflation monster -- health care reform, to its great credit, does. We can nudge providers and customers away from pay-for-service, which rewards over-treatment. We can increase cost-sharing to help patients react to prices, increase transparency and quality through exchanges, and so on. But these are efforts, not answers. If we waited for the messianic Answer to health care inflation, we might never act on the budget. I can't imagine that's what Kevin would prefer. Instead, we should make the changes we can make today, slowly.

It is unfair because Kevin Drum is right: any effort to reduce the deficit that is not 98% health care reform is indeed not serious.

It is unfair because the things that Derek Thompson implies that Kevin does not talk about--"We can nudge providers and customers away from pay-for-service, which rewards over-treatment. We can increase cost-sharing to help patients react to prices, increase transparency and quality through exchanges, and so on. But these are efforts, not answers. If we waited for the messianic Answer to health care inflation, we might never act on the budget. I can't imagine that's what Kevin would prefer. Instead, we should make the changes we can make today, slowly"--are the kinds of things Kevin regularly talks about.

And it is unfair because Simpson and Bowles don't talk about how they are going to achieve any of this. Indeed, their only concrete, legislative, ready-to-go proposal is to raise the deficit from health care above its current-law baseline level: "Replace cuts required by SGR through 2015 with modest reductions while directing CMS to establish a new payment system, beginning in 2015, to reduce costs and improve quality."

http://www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/CoChair_Draft.pdf

November 11, 2010

Liveblogging World War II: November 12, 1940

Winston Churchill:

The Prime Minister (Mr. Churchill) : Since we last met, the House has suffered a very grievous loss in the death of one of its most distinguished Members and of a statesman and public servant who, during the best part of three memorable years, was first Minister of the Crown.

The fierce and bitter controversies which hung around him in recent times were hushed by the news of his illness and are silenced by his death. In paying a tribute of respect and of regard to an eminent man who has been taken from us, no one is obliged to alter the opinions which he has formed or expressed upon issues which have become a part of history; but at the Lychgate we may all pass our own conduct and our own judgments under a searching review. It is not given to human beings, happily for them, for otherwise life would be intolerable, to foresee or to predict to any large extent the unfolding course of events. In one phase men seem to have been right, in another they seem to have been wrong. Then again, a few years later, when the perspective of time has lengthened, all stands in a different setting. There is a new proportion. There is another scale of values. History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days. What is the worth of all this? The only guide to a man is his conscience; the only shield to his memory is the rectitude and sincerity of his actions. It is very imprudent to walk through life without this shield, because we are so often mocked by the failure of our hopes and the upsetting of our calculations; but with this shield, however the fates may play, we march always in the ranks of honour.

It fell to Neville Chamberlain in one of the supreme crises of the world to be contradicted by events, to be disappointed in his hopes, and to be deceived and cheated by a wicked man. But what were these hopes in which he was disappointed? What were these wishes in which he was frustrated? What was that faith that was abused? They were surely among the most noble and benevolent instincts of the human heart—the love of peace, the toil for peace, the strife for peace, the pursuit of peace, even at great peril and 1618 certainly to the utter disdain of popularity or clamour. Whatever else history may or may not say about these terrible, tremendous years, we can be sure that Neville Chamberlain acted with perfect sincerity according to his lights and strove to the utmost of his capacity and authority, which were powerful, to save the world from the awful, devastating struggle in which we are now engaged. This alone will stand him in good stead as far as what is called the verdict of history is concerned.

But it is also a help to our country and to our whole Empire, and to our decent faithful way of living that, however long the struggle may last, or however dark may be the clouds which overhang our path, no future generation of English-speaking folks—for that is the tribunal to which we appeal—will doubt that, even at a great cost to ourselves in technical preparation, we were guiltless of the bloodshed, terror and misery which have engulfed so many lands and peoples, and yet seek new victims still. Herr Hitler protests with frantic words and gestures that he has only desired peace. What do these ravings and outpourings count before the silence of Neville Chamberlain's tomb? Long and hard, hazardous years lie before us, but at least we entered upon them united and with clean hearts...

DeLong Smackdown Watch: Walras' Law and Say's Law Edition

Nick Rowe asks:

What Does Cutting-Edge Macroeconomics Tell Us About Economic Policy for the Recovery?: You see, Say(1803) (lovely way to express this, by the way) was very nearly right. Suppose we start in equilibrium, then there's a sudden desire to stop buying newly-produced goods and buy land instead. Either the price of land rises to equilibrium or it doesn't. If the price of land rises to equilibrium, then people stop wanting to buy land and return to buying newly-produced goods. If the price of land stays fixed (it's sticky, or whatever) people cannot buy land because nobody is willing to sell. So they have to buy something else with their income instead, or else hoard money.

Ultimately there are only two things an individual can do with his income, if everybody else is trying to do the same thing: buy newly-produced goods, where there are plenty of willing sellers in a general glut; or hoard money, by not buying things, which nobody else can stop you doing.

And:

What Does Cutting-Edge Macroeconomics Tell Us About Economic Policy for the Recovery?: OK Brad, a challenge for you:

A general glut means an excess supply of newly-produced goods. You say that a general glut can be caused by an excess demand for financial assets: which could be money, bonds, or safe assets. Is it theoretically possible for a general glut to be caused by an excess demand for something that is neither a financial asset nor a newly-produced good? For example, could it be caused by an excess demand for: land, old houses, old books, antique furniture etc.? Or, what about intermediate cases, like an excess demand for gold, where new and old gold is identical, but new production is very small and inelastic compared to the existing stock?

My position is that a general glut can only be caused by an excess demand for the medium of exchange. An excess demand for any of those other assets can only cause a general glut if it spills over into an excess demand for the medium of exchange. The distinction between financial and non-financial assets is irrelevant. Why should it matter?

I'm trying to smoke out your inner quasi-monetarist!

The way Say expresses it in 1803 is roughly as follows: nobody makes anything unless they intend to use it or sell it, and nobody sells anything unless they intend to buy something with the proceeds of the sale. Thus, "by the metaphysical necessity of the case," as John Stuart Mill was to put it, there has to be the purchasing power to buy everything offered for sale--there can be particular gluts of commodities, but every market in which there is excess supply must be balanced by another in which there is excess demand.

This is an anticipation of what we now call Walras' Law: that the sum across all markets of all excess demands must equal zero. And it was John Stuart Mill who pointed out the hole in Say's argument: you can have an excess supply of all currently produced goods and services if you have an excess demand for financial assets, specifically for money. As Mill put it:

Although he who sells, really sells only to buy, he needs not buy at the same moment when he sells.... [I]t may very well occur that there may be... a very general inclination to sell with as little delay... accompanied with an equally general inclination to defer all purchases.... It is true that this state can be only temporary and must even be succeeded by a reaction of corresponding violence... [but] this is no more than may be said of every partial over-supply.... It must, undoubtedly, be admitted that there cannot be an excess of all other commodities and an excess of money at the same time. But those who have... affirmed that there was an excess of all commodities never pretended that money was one of these commodities.... What it amounted to was that persons in general... liked better to possess money than any other commodity. Money, consequently, was in request, and all other commodities were in comparative disrepute...

Where I think Mill's explanation is incomplete is in his reference to "money... in request, and all other commodities... in comparative disrepute." When money is in request and all other commodities in disrepute, one of those commodities is corporate bonds. Hence people should be dumping corporate bonds as they try to build up their cash holdings. Hence the prices of corporate bonds should be low. But in 2001 we had relatively high prices of corporate and government bonds--low interest rates all across the board--so that there wasn't a shortage of money in particular. What there was was a shortage of savings vehicles for carrying purchasing power from the present into the future, a shortage of bonds and other assets that serve as such savings vehicles--and money is one such vehicle. And today we have relatively high prices for government bonds and other safe assets. What there is a shortage of safe assets--and money is one such safe asset.

This matters because the monetarist cure for a downturn--for a general glut of currently-produced commodities--is to expand the money stock via open market operations, via purchases of short-term government bonds for cash. When the key excess demand in financial markets is an excess demand for money, that works: you expand the supply of money and reduce the excess demand for cash and so people are no longer scrambling to cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services to build up their cash balances.

However, things are different when the key excess demand is a demand for savings vehicles or for safe assets. Here, I think, the zero bound on interest rates is crucial. Bonds can go to par at which point they become perfect substitutes for cash and cannot go any higher. Other safe nominal assets can go to par at which point they become perfect substitutes for cash and cannot go any higher. And that zero-bound property is what gets the economy stuck in a general glut.

When the key excess demand is a demand for savings vehicles--for bonds--open-market operations don't work: you buy bonds for cash but you haven't done anything about the excess demand for bonds, bonds go to par and cannot go any higher and there is still an excess demand for bonds, and so people keep scrambling to cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services to build up their bond balances. And when the key excess demand is a demand for safe high quality assets, open-market operations still don't work: you buy safe government bonds for cash but you haven't done anything about the excess demand for safe assets, all safe assets go to par and cannot go any higher and there is still an excess demand for bonds, and so people keep scrambling to cut back on their spending on currently-produced goods and services to build up their safe asset balances.

But suppose the excess demand were for some other non-currently produced asset--Nick's examples are land, old houses, old books, and antique furniture--could that produce a general glut? Walras Law would say yes, I think. But it would also say that the monetarist cure--buy bonds for cash--would alleviate the problem: create an excess supply of money and people will try to spend down their cash balances and that will boost demand for currently-produced goods and services, leaving you with an excess demand for old furniture and an excess supply of money.

It is the fact that the key excess demand is for a broader financial asset class than mere cash money that is, I think, the key to why the monetarist cure is likely to fail--or at least to be supplemented by policies that make sure that not just the supply of liquid cash money but the supply of safe assets in general or savings vehicles in general increases in order to cure a downturn.

It Is Not Just for the Sake of Journalism That We Need to Shut the Washington Post Down Today

It looks as though the Post has become a deeply corrupt and disfunctional educational company. Matthew Yglesias:

Yglesias » Kaplan, Inc: The Washington Post company['s] biggest source of revenue is... Kaplan... its low-performing for-profit university unit is its biggest source of growth as Tamar Lewin points out in an excellent NYT piece:

Over the last decade, Kaplan has moved aggressively into for-profit higher education, acquiring 75 small colleges and starting the huge online Kaplan University. Now, Kaplan higher education revenues eclipse not only the test-prep operations, but all the rest of the Washington Post Company’s operations.... [O]nly 28 percent of Kaplan’s students were repaying their student loans. That figure is well below the 45 percent threshold that most programs will need to remain fully eligible for the federal aid on which they rely....

[T]he basic business model of the Washington Post Company... is... [to] say “in exchange for paying us money, we’ll provide you education services that pay off in the long run.” Potential customers... avail themselves of taxpayer-subsidized loans in order to take the Post up on their offer. But 72 percent of the Post’s customers find that they’re actually unable to repay those taxpayer-subsidized loans.... [T]he Obama administration has proposed that taxpayers stop subsidizing programs with dismal performance rates.... [T]he Post would prefer to keep on getting free money from taxpayers and thus “spent $350,000 on lobbying in the third quarter of this year, more than any other higher-education company.”... Donald Graham has personally “gone to Capitol Hill to argue against the regulations in private visits with lawmakers... [h]is newspaper, too, has editorialized against the regulations.”... [E]very member of congress is now on notice that the city’s most influential newspaper is prepared to go to bat for its corporate partners.

Shut it down today, please.

Macro Advisers: Okun's Law Is Working Well. Nothing to See Here. Move Along

There has long been some question of whether there is something to explain in divergence between production and employment in this downturn. Macro Advisors says not:

Macroadvisers: Swings in Hours and Productivity in the Recession and Recovery — Unusual or Not?: Our model for hours understands the recent experience of hours, and given actual data on output, it therefore explains most of the swings in productivity over the last few years. Stated simply, nearly the entire decline in hours between the second quarter of 2007 and the third quarter of 2009, as well as most of the surge in productivity that occurred in 2009 and early 2010, is accounted for by the model. The model also easily accounts for the softening of productivity in the second quarter and it more than accounts for the rebound in productivity in the third quarter.

The model understands these swings to be due largely to cyclical factors, including changes in output and in labor utilization, and in changes in the growth of business capital stocks. Movements in total factor productivity (TFP) have for the most part been a secondary factor in accounting for swings in productivity and hours in recent years — except in the second quarter, when a temporary weakening in TFP growth contributed to the decline in productivity. The model more than accounts for the rebound in productivity growth in the third quarter. Indeed, it “expected” an increase 1.1 percentage points larger than actually occurred, reflecting both a positive swing in the cyclical contribution and a rebound in TFP growth.

Some have argued that productivity was inexplicably strong during the recent surge. A possible reason is that employers might have slashed their labor forces by more than what was warranted out of concern that demand would weaken by substantially more than it did. As a result, productivity was unsustainably high. However, we are not inclined to agree because our model understands well both the level and recent growth of productivity.

Harold Pollack on Barack Obama

Harold:

President Obama: I love you, but you need to raise your game: Judging by recent press reports, the White House is apparently folding on the Bush tax cuts for people with incomes exceeding $250,000. On several levels, this is one of the most depressing episodes of the entire Obama presidency.... [C]aving in on this issue amounts to bad social and fiscal policy. (See Jonathan Chait’s several hundred columns making the rubble bounce on this theme.) The Bush tax cuts on the $250,000+ group squander $700 billion over the next decade. Especially in these hard times, when it’s a heavy political lift to finance basic services, that is vastly irresponsible.... People who earn more than $250,000 per year can afford to pay a few percentage points more, as they did during the Clinton era....

[T]he Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculates that permanent extension of Bush tax cuts for upper-income taxpayers has an almost eerily similar impact on federal deficits as does the entire unfunded liability of our Social Security system. Somehow, all that scary talk about deficits and Social Security’s genuine but manageable long-term shortfall doesn’t carry over to this numerically equivalent issue in tax policy.

Perhaps most depressing, this episode illustrates the periodic preemptive surrenders that are frustrating to the President’s closest supporters....

To give up on this issue backtracks on a clear campaign plank... concedes to Republicans a mandate they have not earned.... The “American people” do not support tax cuts for the wealthy. Nor, for that matter, do majorities support the deficit commission’s fundamentally conservative vision of limited government....

President Obama.... I am one of your proud and strong supporters. I will continue to be. Yet it’s time for you to raise your game...

The Depressing Thing Is That Neither Conrad Nor Stephanopoulos Thinks There Is Anything Strange About This...

George Stephanopoulos writes:

Sen. Conrad: Extend All Tax Cuts; Time to Get 'Serious' About Deficit.

Why oh why can't we have a better press corps? Why oh why can't we have better senators?

The Last Word on Simpson-Bowles: What Kevin Drum Said

Simpson and Bowes are simply not serious. Oursourced to Kevin Drum:

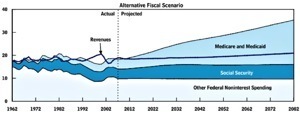

Is the Deficit Commission Serious? | Mother Jones: I've been trying to figure out whether I have anything to say about the "chairman's mark" of the deficit commission report that was released today. In a sense, I don't. This is not a piece of legislation, after all. Or a proposed piece of legislation. Or even a report from the deficit commission itself. It's just a draft presentation put together by two guys. Do you know how many deficit reduction proposals are out there that have the backing of two guys? Thousands. Another one just doesn't matter. But the iron law of the news business is that if people are talking about it, then it matters. So this report matters, even though it's really nothing more than the opinion of Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles. So here's what I think of it, all contained in one handy chart....

Discretionary spending (the light blue bottom chunk) isn't a long-term deficit problem. It takes up about 10% of GDP forever. What's more, pretending that it can be capped is just game playing: anything one Congress can do, another can undo. So if you want to recommend a few discretionary cuts, that's fine. Beyond that, though, the discretionary budget should be left to Congress since it can be cut or expanded easily via the ordinary political process. That's why it's called "discretionary."

Social Security (the dark blue middle chunk) isn't a long-term deficit problem. It goes up very slightly between now and 2030 and then flattens out forever. If Republicans were willing to get serious and knock off their puerile anti-tax jihad, it could be fixed easily with a combination of tiny tax increases and tiny benefit cuts phased in over 20 years that the public would barely notice. It deserves about a week of deliberation.

Medicare, and healthcare in general, is a huge problem. It is, in fact, our only real long-term spending problem.

To put this more succinctly: any serious long-term deficit plan will spend about 1% of its time on the discretionary budget, 1% on Social Security, and 98% on healthcare. Any proposal that doesn't maintain approximately that ratio shouldn't be considered serious. The Simpson-Bowles plan, conversely, goes into loving detail about cuts to the discretionary budget and Social Security but turns suddenly vague and cramped when it gets to Medicare. That's not serious.

There are other reasons the Simpson-Bowles plan isn't serious. Capping revenue at 21% of GDP, for example. The plain fact is that over the next few decades Social Security will need a little more money and healthcare will need a lot more. That will be true even if we implement the greatest healthcare cost containment plan in the world. Pretending that we can nonetheless cap revenues at 2000 levels isn't serious.

And their tax proposal? As part of a deficit reduction plan they want to cut taxes on the rich and make the federal tax system more regressive? That's not serious either.

Bottom line: this document isn't really aimed at deficit reduction. It's aimed at keeping government small. There's nothing wrong with that if you're a conservative think tank and that's what you're dedicated to selling. But it should be called by its right name. This document is a paean to cutting the federal government, not cutting the federal deficit.

Worst Things About Simpson-Bowles

On Thu, Nov 11, 2010 at 6:04 AM, Sydelle Moore XXXXX@thehill.com wrote:

The Big Question: What is the best and the worst recommendation from the president's debt commission?

Well, two things tie for the worst thing about the president's deficit-reduction commission.

The first is Barack Obama's decision to take a long-time budget arsonist like Alan Simpson--somebody who never found a budget-busting Republican initiative he could not vote for or a deficit-reducing Democratic initiative he could not vote against--and give him a fire chief's hat. As a result, Alan Simpson's ideas are now not Alan Simpson's ideas but instead the "recommendation[s][ from the president's debt commission."

The second is the capping of federal health spending growth at GDP+1%/year. That means that, adjusting the aging of the population, the government is supposed to spend a smaller share of incomes on health care as each year passes. That would require not just the repeal of the Affordable Care Act but the elimination of Medicare as we know it.

The best idea... is it cutting schools for soldiers' kids? Or is it paying for reductions in the top income tax rate by cutting the Earned Income Tax Credit so that there are once again lots of families in America where a parent works full time and yet the kids are still in poverty?

Yours,

Brad DeLong

Keeping the Fourth Online-Learning Revolution from Flaming Out into Disaster

Most people do not know that our current online-learning revolution is actually the fourth. The first was made by Aristocles son of Ariston and Aristoteles son of Nicomachus when they created the philosophy book to help those who could not find or could not afford their own personal Sokrates to learn. The second came with the invention of the medieval university so that those who could not afford to buy and own all the books they needed could nevertheless meet in groups to hear them read aloud and take notes. The third came with Gutenberg's making books cheap enough so that intellectuals could own all that they wanted. And the fourth is today.

We will not manage the fourth revolution unless we first figure out why the third revolution--that eliminated the original raison d'etre of the medieval university did not destroy but rather strengthened the university. What, exactly, were the useful intellectual functions that the university performed that meant that it could not be fully replaced by sitting on a log under a tree surrounded by your stack of books?

My outline of the problem is here.

Commenters respond:

eightnine2718281828mu5 said: "What is it about the institution of the university that allowed it to survive the third online-learning revolution?" signalling

Omega Centauri said: Beyond signalling, which is important, I think we need some interactive intelligence. Its tough to get a deeply challenging subject mastered from online stuff alone. What if I don't really understand the Poincare conjecture? (Heck I can't even spell it). Will that mean that by about chapter 11 I'll hit some intellectual brickwall I don't know how to get through? If I had a sharp teacher, he could insure some crucial but tricky foundational principle is really mastered. But, online (and in a hurry usually), its just to easy to slip past something important, then find out too late that you've build your whole intellectual understanding of XXX -on a house of cards.... Now, even really good wetware computers (actual flesh and blood neuronal processors) have trouble doing this. Training a computer to..... Wish I had a clue.

jeremy said: I thought you were actually going to comment on how today's distance learning is 4th rate...I am thinking of the U of Phoenix, and other for-profit distance learning programs. There are some decent distance learning opportunities available. For instance, while I lived in Germany I used archives of recorded calculus courses from a university in North Carolina to learn 1st year calculus. I also took a 4th year statistics course online through Iowa State. Those courses served a very specific purpose, but the lecturer's impact was not very high. The interaction level was near zero for me, but I learned the material. I probably could have just read the books and done some of the problems at the end of each chapter and done just as well on the tests. It's really tough for a first rate mind to give you a first rate lecture through distance learning. I don't even think lecturers try; you might as well just find out what the book is, read it on your own, and later find a better class a few levels up at a campus nearby.

MBH said: "No philosopher understands his predecessors until he has re-thought their thought in his own contemporary terms." PF Strawson. As an online PhD student who studied undergraduate philosophy at a brick and mortar school, I agree with the above comments that signaling and interaction preserved the university after the cost of books could have made it obsolete. But not just any kind of signaling: hinting in the Wittgensteinian sense. For instance, if I start to read Kant -- online -- without any background, his metaphysics may baffle me. But if the facilitator presents a supplemental lecture that proposes "For Kant, phenomena is to software as noumena is to hardware..." then I can go on. And not just any kind of interaction either. To make sure the class understands, the facilitator may begin a thread in which every student must rephrase an aspect of Kant's metaphysics in their own words. Whether the rephrasing matches or mismatches the meaning, the facilitator can track the students' understanding. That would prevent the problem that Omega raises above.

Hopefuly Anonymous said: universities, and lectures for that matter, provide paternalistic structure for those that lack autodidactic discipline. We should make it easier for those with autodidactic discipline to get credentialed (licensing exams) without trying to extract wealth from them or creating other inefficient barriers.

Pat D said: I propose there were actually five revolutions. The first 3 are the same as what you propose above. But along the way, the quantity of first-rate thinkers increased due to earlier revolutions. Therefore, the fourth revolution is each classroom apprenticed to a (near-)first-rate thinker, rather than being read the work of a first-rate thinker. In other words, the best classrooms today are not following the lector style, but are instead akin to Socrates teaching a group of students. Your proposed fifth revolution is about decreasing the price of a service provided by the fourth revolution. In a broader sense of online learning, you don't need to worry about it going bust - Wikipedia is increasingly popular, and MIT provides free lectures via iTunes University. UPhoenix is just the "missing link" in this evolution, one that we should not worry about going extinct.

Jed Harris said: Why do these answers focus on the student - teacher or student - content relationship, when the student - student interaction looms so large in the actual experience? Teaching and content are useful, but peer interaction is an essential part of the process -- quite possibly the most essential part. Even for very content intensive domains. Look at the student groups studying together in the engineering library. Look at how graduate students spend time in their offices and labs. Even the university doesn't value or facilitate this mutual support nearly enough. Current distance learning makes it nearly impossible.

derek said: Books were cheaper than your own personal Socrates, but still expensive, and still not a substitute for your own personal Socrates. Universities arose to address the "still expensive" part, but they survived the printing press by evolving to address the "still no substitute for your own personal Socrates" part. (when i went to uni we really did have our own personal Socrates; that was his actual name)

bad Jim said: Perhaps it was the explosive growth of knowledge which accompanied the printing press that made the university even more valuable than before. Before Gutenberg, and the Reformation, the chief output of the university was clerics; afterwards the output included lawyers and physicians and most crucially teachers of all kinds, because learning had become valuable to accountants and mechanics and sailors and so on. With the invention of science universities became the place where science was mostly taught and mostly done, and it remains so to this day. It may not be beside the point that the work of a student is facilitated by living among other students whose lives are similarly devoted and governed by the same schedule, or that there are synergies produced by a concentration of bright and motivated young people. Although it's possible for a serious student to educate itself with nothing but a large enough library, it doesn't happen often enough to be considered a serious alternative. The internet hardly changes that.

Greg said: Different types of leverage. The book was a simple force multiplier, allowing the thoughts of the thinker to be absorbed by more people. The university system, as well as further multiplying force (at the cost of some imperfections), also had a large element of guidance. This guidance is the quality that guaranteed the survival of the university system when printed books came. The printed book was again a simple force multiplier, but vastly more powerful than the scribe-written book. It enabled the expansion of the university system among other effects. The next form of instruction must retain the guidance introduced with the university, and must require less labour from the teacher, who can then focus on the students for whom the regular guidance is not working. In this way, the work of the teacher will be leveraged. Aplia and companies like it are making a start on this. However, the next major step suggested by the "force multiplier versus guidance" analysis is a new guidance system: instructional software that can monitor the student's eye tracking and other behaviour in real time, ask questions, and adapt the instruction in real time to deal with incomprehension, loss of focus, and so on, in exactly the same way that a one-on-one tutor does now. It shouldn't be hard to get something that does 80 percent of the job and knows when to kick the problem upstairs. This "force multiplies" the guidance provided at universities. Obviously the above does not apply to leading-edge graduate study, which must still be operated on the apprentice/collegial system, but to undergraduate/early graduate teaching and to labour force skill acquisition.

Greg said in reply to Jed Harris: "Teaching and content are useful, but peer interaction is an essential part of the process -- quite possibly the most essential part." Yes, students learn from each other because they can't afford personal tutors. Affordable computation and machine vision should allow us to change this.

Neal said: The basis of learning to date is accountability. While there is nebulous blather about the importance of face-to-face, the real value of face-to-face was in accountability. You were there, you were expected to learn, and you were expected to produce evidence of your learning. People, and especially students, are weaselly creatures. I was a student, I know people who have students, and I am a father to students. They are weaselly creatures. The danger to the value of an on-line education is the pretending that the weaselly factor does not exist. The embedded nature of what was learned in the face-to-face accountability is replaced by what? I know how my children skitter and skate through the "inter-web net-tubey" thing and there is very little of value that remains after the interaction. Quick solutions seized from here and there, on-line boards and chats for the "smart" persons answer, "cut and paste", done, and on to another round of COD4.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers