J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2150

November 26, 2010

John Taylor vs. John Taylor

John Taylor, 2010:

[T]he Federal Reserve's large-scale asset purchase plan (so-called "quantitative easing") should be reconsidered and discontinued. We do not believe such a plan is necessary or advisable under current circumstances.... [I] disagree with the view that inflation needs to be pushed higher, and worry that another round of asset purchases, with interest rates still near zero over a year into the recovery, will distort financial markets...

John Taylor, 1994:

[A] good policy allows a speedup in growth above potential GDP growth after a recession.... The faster growth in the United States compared with that in Europe just after the 1982 recession is an example of such a better policy.... [O]ne rule I have found attractive has the federal funds rate adjusted up if GDP goes above target or if inflation goes above target, and vice versa...

Battered but Not Beaten

My Talk for the October 29 Berkeley IRLE "New Deal or No Deal?" Conference:

Open publication - Free publishing - More macroeconomics

20101029 Battered and Beaten.pdf

Why Iceland Is Doing Better than Ireland

Paul Krugman:

Eating the Irish: [A]t this point Iceland seems, if anything, to be doing better than its near-namesake. Its economic slump was no deeper than Ireland’s, its job losses were less severe and it seems better positioned for recovery. In fact, investors now appear to consider Iceland’s debt safer than Ireland’s. How is that possible?

Part of the answer is that Iceland let foreign lenders to its runaway banks pay the price of their poor judgment, rather than putting its own taxpayers on the line to guarantee bad private debts. As the International Monetary Fund notes — approvingly! — “private sector bankruptcies have led to a marked decline in external debt.” Meanwhile, Iceland helped avoid a financial panic in part by imposing temporary capital controls — that is, by limiting the ability of residents to pull funds out of the country.

And Iceland has also benefited from the fact that, unlike Ireland, it still has its own currency; devaluation of the krona, which has made Iceland’s exports more competitive, has been an important factor in limiting the depth of Iceland’s slump.

None of these heterodox options are available to Ireland, say the wise heads. Ireland, they say, must continue to inflict pain on its citizens — because to do anything else would fatally undermine confidence.

But Ireland is now in its third year of austerity, and confidence just keeps draining away. And you have to wonder what it will take for serious people to realize that punishing the populace for the bankers’ sins is worse than a crime; it’s a mistake.

The Column That I, Now Green with Envy, Wish That I Had Written

Paul Krugmnan:

The Instability of Moderation - NYTimes.com: Brad DeLong writes of how our perception of history has changed in the wake of the Great Recession. We used to pity our grandfathers, who lacked both the knowledge and the compassion to fight the Great Depression effectively; now we see ourselves repeating all the old mistakes. I share his sentiments.

But watching the failure of policy over the past three years, I find myself believing, more and more, that this failure has deep roots – that we were in some sense doomed to go through this. Specifically, I now suspect that the kind of moderate economic policy regime Brad and I both support – a regime that by and large lets markets work, but in which the government is ready both to rein in excesses and fight slumps – is inherently unstable. It’s something that can last for a generation or so, but not much longer.

By “unstable” I don’t just mean Minsky-type financial instability, although that’s part of it. Equally crucial are the regime’s intellectual and political instability.

Intellectual instability:

The brand of economics I use in my daily work – the brand that I still consider by far the most reasonable approach out there – was largely established by Paul Samuelson back in 1948, when he published the first edition of his classic textbook. It’s an approach that combines the grand tradition of microeconomics, with its emphasis on how the invisible hand leads to generally desirable outcomes, with Keynesian macroeconomics, which emphasizes the way the economy can develop magneto trouble, requiring policy intervention. In the Samuelsonian synthesis, one must count on the government to ensure more or less full employment; only once that can be taken as given do the usual virtues of free markets come to the fore.

It’s a deeply reasonable approach – but it’s also intellectually unstable. For it requires some strategic inconsistency in how you think about the economy. When you’re doing micro, you assume rational individuals and rapidly clearing markets; when you’re doing macro, frictions and ad hoc behavioral assumptions are essential.

So what? Inconsistency in the pursuit of useful guidance is no vice. The map is not the territory, and it’s OK to use different kinds of maps depending on what you’re trying to accomplish: if you’re driving, a road map suffices, if you’re going hiking, you really need a topo.

But economists were bound to push at the dividing line between micro and macro – which in practice has meant trying to make macro more like micro, basing more and more of it on optimization and market-clearing. And if the attempts to provide “microfoundations” fell short? Well, given human propensities, plus the law of diminishing disciples, it was probably inevitable that a substantial part of the economics profession would simply assume away the realities of the business cycle, because they didn’t fit the models.

The result was what I’ve called the Dark Age of macroeconomics, in which large numbers of economists literally knew nothing of the hard-won insights of the 30s and 40s – and, of course, went into spasms of rage when their ignorance was pointed out.

Political instability:

It’s possible to be both a conservative and a Keynesian; after all, Keynes himself described his work as “moderately conservative in its implications.” But in practice, conservatives have always tended to view the assertion that government has any useful role in the economy as the thin edge of a socialist wedge. When William Buckley wrote God and Man at Yale, one of his key complaints was that the Yale faculty taught – horrors! – Keynesian economics.

I’ve always considered monetarism to be, in effect, an attempt to assuage conservative political prejudices without denying macroeconomic realities. What Friedman was saying was, in effect, yes, we need policy to stabilize the economy – but we can make that policy technical and largely mechanical, we can cordon it off from everything else. Just tell the central bank to stabilize M2, and aside from that, let freedom ring!

When monetarism failed – fighting words, but you know, it really did — it was replaced by the cult of the independent central bank. Put a bunch of bankerly men in charge of the monetary base, insulate them from political pressure, and let them deal with the business cycle; meanwhile, everything else can be conducted on free-market principles.

And this worked for a while – roughly speaking from 1985 to 2007, the era of the Great Moderation. It worked in part because the political insulation of central banks also gave them more than a bit of intellectual insulation, too. If we’re living in a Dark Age of macroeconomics, central banks have been its monasteries, hoarding and studying the ancient texts lost to the rest of the world. Even as the real business cycle people took over the professional journals, to the point where it became very hard to publish models in which monetary policy, let alone fiscal policy, matters, the research departments of the Fed system continued to study counter-cyclical policy in a relatively realistic way.

Financial instability:

Last but not least, the very success of central-bank-led stabilization, combined with financial deregulation – itself a by-product of the revival of free-market fundamentalism – set the stage for a crisis too big for the central bankers to handle. This is Minskyism: the long period of relative stability led to greater risk-taking, greater leverage, and, finally, a huge deleveraging shock. And Milton Friedman was wrong: in the face of a really big shock, which pushes the economy into a liquidity trap, the central bank can’t prevent a depression.

And by the time that big shock arrived, the descent into an intellectual Dark Age combined with the rejection of policy activism on political grounds had left us unable to agree on a wider response.

In the end, then, the era of the Samuelsonian synthesis was, I fear, doomed to come to a nasty end. And the result is the wreckage we see all around us.

We could go the other way--we could make micro about myopia: about psychological, behavioral, and institutional myopia. Then micro and macro would fit together in a stable whole, and the research frontier would be all about proper institution design.

The Retreat of Macroeconomic Policy: The Column I Wrote

Project Syndicate: The Retreat of Macroeconomic Policy by J. Bradford DeLong:

BERKELEY – One disturbing thing about studying economic history is how things that happen in the present change the past – or at least our understanding of the past. For decades, I have confidently taught my students about the rise of governments that take on responsibility for the state of the economy. But the political reaction to the Great Recession has changed the way we should think about this issue.

Governments before World War I – and even more so before WWII – did not embrace the mission of minimizing unemployment during economic downturns. There were three reasons, all of which vanished by the end of WWII.

First, there was a hard-money lobby: a substantial number of rich, socially influential, and politically powerful people whose investments were overwhelmingly in bonds. They had little personally at stake in high capacity utilization and low unemployment, but a great deal at stake in stable prices. They wanted hard money above everything.

Second, the working classes that were hardest-hit by high unemployment generally did not have the vote. Where they did, they and their representatives had no good way to think about how they could benefit from stimulative government policies to moderate economic downturns, and no way to reach the levers of power in any event.

Third, knowledge about the economy was in its adolescence. Knowledge of how different government policies could affect the overall level of spending was closely held. With the exception of the United States’ free-silver movement, it was not the subject of general political and public intellectual discussion.

All three of these factors vanished between the world wars. At least, that is what I said when I lectured on economic history back in 2007. Today, we have next to no hard-money lobby, almost all investors have substantially diversified portfolios, and nearly everybody suffers mightily when unemployment is high and capacity utilization and spending are low.

Economists today know a great deal more – albeit not as much as we would like – about how monetary, banking, and fiscal policies affect the flow of nominal spending, and their findings are the topic of a great deal of open and deep political and public intellectual discussion. And the working classes all have the vote.

Thus, I would confidently lecture only three short years ago that the days when governments could stand back and let the business cycle wreak havoc were over in the rich world. No such government today, I said, could or would tolerate any prolonged period in which the unemployment rate was kissing 10% and inflation was quiescent without doing something major about it.

I was wrong. That is precisely what is happening.

How did we get here? How can the US have a large political movement – the Tea Party – pushing for the hardest of hard-money policies when there is no hard-money lobby with its wealth on the line? How is it that the unemployed, and those who fear they might be the next wave of unemployed, do not register to vote? Why are politicians not terrified of their displeasure?

Economic questions abound, too. Why are the principles of nominal income determination, which I thought largely settled since 1829, now being questioned? Why is the idea, common to John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, Knut Wicksell, Irving Fisher, and Walter Bagehot alike, that governments must intervene strategically in financial markets to stabilize economy-wide spending now a contested one?

It is now clear that the right-wing opponents to the Obama administration’s policies are not objecting to the use of fiscal measures to stabilize nominal spending. They are, instead, objecting to the very idea that government should try to serve a stabilizing macroeconomic role.

Today, the flow of economy-wide spending is low. Thus, US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke is moving to have the Fed boost that flow by changing the mix of privately held assets as it buys government bonds that pay interest in exchange for cash that does not.

That is entirely standard. The only slight difference is that the Fed is buying seven-year Treasury notes rather than three-month Treasury bills. It has no choice: the seven-year notes are the shortest-duration Treasury bonds that now pay interest. The Fed cannot reduce short-term interest rates below zero, so it is attempting via this policy of “quantitative easing” to reduce longer-term interest rates.

Yet America’s right wing objects to this, for reasons that largely remain mysterious: what, at the level of economic theory, is the objection to quantitative easing? Blather about Federal Reserve currency manipulation and excessive risk-taking is not worthy of an answer.

Still, here we are. The working classes can vote, economists understand and publicly discuss nominal income determination, and no influential group stands to benefit from a deeper and more prolonged depression. But the monetarist-Keynesian post-WWII near-consensus, which played such a huge part in making the 60 years from 1945-2005 the most successful period for the global economy ever, may unravel nonetheless.

The Social Studies Major 50th Anniversary Celebration Party and Bitter Internal Ideological Power Struggle

By my rough count, one-third the people who had ever taught in and one-fourteenth of those who had ever graduated from Harvard's Social Studies major showed up in Cambridge, Massachusetts on the last Saturday in September this year for the major's fiftieth-anniversary celebration and bitter internal ideological power struggle. And that is not counting those graduates who did not attend but looked on via the Internet, or those outsiders--Nick Kristof, James Fallows--who felt compelled to comment on the exercise.

That is, I think testimony to the amazing intellectual strength of the program.

And, indeed, as one senior member of the faculty said, those who came to the party got just what they bargained for: serious engagement with political action and moral responsibility at a rarified intellectual level rarely seen on this green earth.

For example, the Q-and-A period of the afternoon panel:

Elliott Prasse-Freeman: This question is for Ms. Gorelick. I want to start with Professor Walzer's invocation to take "theoretical imperialism" seriously. While I do not agree with his rubbishing of Foucault, I do think that it is a good thing to do. I would like to do this in the context of Marty Peretz. I am going to read a Marty Peretz quote. And I want us to think: "what theory comes through here?"

So many of the Black population are afflicted by... cultural deficiencies. I would guess that in the ghetto a lot of mothers do not appreciate the importance of schooling...

What kind of theory comes through here?

Do we have an account of biopolitics, perhaps?

Differential access to resources and opportunities that, perhaps, makes education less desirable for certain populations?

Nope.

It's just either stupid, or racist, or both.

So now I turn my question to you, Ms Gorelick: a person who has that kind of model for the world--what kind of teaching can they really be doing? If they have that much hatred of one entire aspect of humanity, what exactly would they be teaching you?

I finish my little diatribe by asking you to defend such a disgusting person, and also to say that people like you allow him to have the power that he does. (applause)

Jamie Gorelick: He was a fantastic teacher. He was generous with his time. He encouraged debate. He encouraged us in our studies. And we honor him for that by creating a fund to help undergraduates continue their work. Most of us have known Marty for a long time, and we disagree with him on many of his opinions. This is not an endorsement of any particular view. I will tell you that, as Richard Tuck said at the outset, when we heard of this convocation we thought that this would be a nice way to honor a teacher who has meant a lot to many of us. And we sent out notes to people who had had Marty as a tutor, and they responded with contributions and a desire to fund the fellowship. It is pretty much as simple as that. Marty has been a loyal and good friend to many people. He has views that he has explicated and changed, some of which I agree with and some of which I do not. And that is what I have to say. As E.J., who has been a partner with me on this on this effort has said, if anyone could hold two contradictory thoughts in his head at the same time, it should be people in this group, and you can honor someone as a teacher without endorsing everything that they have said.

Nisha Agarwal: I want to make a general comment on the theme of this panel--Social Studies and social change. Let me start by saying, how excited I was to be invited to this event. I did not go to my ten-year college reunion. But when I got the email about this, I signed up immediately (applause). The reason that I am part of a movement for racial justice is this program. So that is the love part that I am going to put out there, before I provide the alienation part. (laughter). Coming here today ,I felt somewhat disappointed and a little bit naive in thinking about the connection between Social Studies and social change. I have really enjoyed the panelists. But I do not feel that the selection of panelists throughout the day reflects the diversity of the communities that Social Studies cares about, writes about, and thinks about. I not think that the curriculum of Social Studies 10--though I saw that Franz Fanon has crept in there--is still very western-centric. And I think, most important, that the decision to honor Marty Peretz who has said things like the previous commentator said, and also said things like "Arab-Americans are hidebound and backwards," is really not my memory of what the Social Studies Committee is about.

I suppose that this is my recommendation for the next fifty years of the program. If there is a true commitment to Social Studies and social change, it will turn a well-developed critical gaze on ourselves. Realize that what happens in rooms like this: who we invite to speak, who we read, and certainly who we choose to honor very much impacts that product of social change that is happening out in the world today. That is my embedded critique. I urge Social Studies to rethink what is going on here today in terms of who is honored and who is invited to speak (applause).

E.J. Dionne: This was an effort to honor a great teacher. I have disagreed with Marty on all kinds of things over the years. I argued with him in a friendly way--and friends can argue, friends can passionately disagree about. Some of the recent comments. I understand the passion that has been aroused by this. I think there is a fascinating division here. It could be the object of some interesting social science. People who knew Marty a long time ago and have worked with him and argued with him and even had disagreements with him understood why people would honor him for the teaching. People who have never met Marty, who have seen some of the stuff that he has written which, as I say, I have disagreed with Marty only know him through that. They don't know that he stood up for the Roma. They don't know that he stood up for gays very early, when others were not. They don't know that he stood up for the Kurds. This is a very complicated person like most of us are. And I think that is the split here. Honoring Marty because we really loved him as a teacher and his passion.... In terms of our speakers, we should have had two days because we could have gotten more voices up here. I have enjoyed this so much and I would stay for a second if I could. Thank you very much. It seems that was a fair comment. (applause)

Michael Walzer: With respect to the previous questioner, I wonder if you have undertaken a survey of everything that every present member of the Social Studies faculty has said in postings, in footnotes, in lectures to make sure that nothing they have said is offensive or hurtful or embarrassing. If you are not doing that, well you had better start doing that because you will find a lot of things that you do not like.

Abdelnassar Rashid: My name is Abdelnassar Rashid and I am a junior in Social Studies. I would like to point out that Social Studies actually did make the decision to honor Martin Peretz. They did meet last Friday and over the weekend. They did finally come to the decision to honor him. It is not just his former students who are doing this. The Standing Committee made the decision itself. One thing to notice is that Marty Peretz has made a pseudo-apology for the latest bigoted thing that he has said. He took back his comment about Muslims not deserving first amendment protections. Since we have three friends on the panel, I would ask you for a commitment to ask him to apologize for twenty-five years of bigotry. Thank you (applause).

Richard Tuck: I let Abdelnassar Rashid speak because he is somebody that I have had dealings with and whose substantive views on this matter I respect. But I do not think it is appropriate for us at the moment to pursue these issues any further. If there is any other question about the substance of the panel I would be reasonable to have that. Otherwise I am afraid that we should accept that this has been a very difficult issue which has understandably throughout our meeting and we should reflect on its implications. Are there any other questions specifically to the points being raised by the panel?...

And Robert Paul Wolff's luncheon talk:

You see before you a coelacanth, a survivor from ancient days swimming up to the surface from the depths of time. I was there at the very start of Social Studies--I have with me the original reading list from 1960-1. Yet when I look at today's Social Studies 10 reading list--it is much the same.

Why is it that the core readings in Social Studies have not changed for fifty years? I will try to answer that question with yet another story from the early days of Social Studies, but it will take me a moment to sketch the background, so bear with me.

In the early '50s, a famous Swarthmore social psychologist named Solomon Asch did an experiment to study the effect of social pressure on belief and perception. [Asch published an article about his research in SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN. You can find it if you Google it.] Briefly, Asch put a small group of young college men in a seminar room and told them he was studying perception. In fact, only one young man was a real subject; the others were Asch's collaborators. Asch then showed the men two cards. On the first were three straight lines of very unequal length. On the second was one line, obviously equal in length to one of the three lines. He asked each student in turn which line on the card of three the single line matched. At first, as he went around the table, everyone gave the same correct answer. But then, as he showed them successive pairs of cards, everyone but the last to be called on [who was the real subject] gave the same obviously wrong answer. The first or second time around, the real subject, looking puzzled or troubled, gave the correct answer, but as the experiment continued, with everyone in the room giving a wrong answer, a significant percentage of the subjects -- more than a third -- started to go along with the group and give the wrong answer also. When Asch interviewed these men later -- the ones who had switched to the wrong answers -- some said they just did not want to "spoil the experiment." Some said that at first they thought everyone was wrong, but after a while they began to think something was wrong with their own judgment. And some even said that although the line chosen by the group looked unequal to the other line, when they looked closely they could see that it was really equal.

The experiment was much commented upon, and everyone took it as distressing evidence of the effects of social pressure on conformity of behavior. But I was interested in another aspect of the experiment. It occurred to me that in order to perform the experiment, Asch had first to take a position on what the correct and incorrect answers were. Otherwise, he would just have statistics about shifting public opinion, which would reveal nothing about the distorting effects of social pressure. Well, obviously, you will say. After all, Asch needed simply to put a ruler down next to the lines and measure them.

I first read the Asch experiment in the early Fall of 1960, just as Social Studies was starting. One day, in October, I ran into Barrington Moore on the street and we stopped to chat. This was during the run-up to the 1960 presidential election in which John F. Kennedy was running against Richard M. Nixon. Everyone at Harvard was mad for Kennedy, of course. He was a Harvard man, his wife spoke French, and he had even won a Pulitzer Prize -- although we did not know then that Ted Sorenson had written the book for which he won the prize. I talked excitedly to Moore about the campaign, and said that I hoped Kennedy would win. Moore looked down his long, aristocratic nose at me and then said, 'There's not a dime's worth of difference between them.' Then he walked on.

I thought that was just Barry being his usual contrarian self, but Kennedy got selected, and the first thing he did was to invade Cuba. The scales fell from my eyes and I realized Barry was right. Now, even back then, social scientists were doing a good deal of public opinion polling, but I thought, 'Wouldn't it be interesting for someone to do a study of why so many voters perceived Kennedy and Nixon as unequal when they were obviously equal?'

'Ah well,' you will say. 'To do such an experiment, the social scientist would have to be able to look beneath the surface appearances of society to the underlying socio-economic reality. AND THAT IS PRECISELY WHAT THE STUDY OF SMITH AND MARX AND DURKHEIM AND FREUD AND WEBER TEACHES US TO DO. Each of these authors, in his different way, goes beneath surface appearances to examine underlying social and economic realities. That is why those authors have been on the reading list for fifty years.

But, you will protest, it is easy enough for Asch to determine whether two lines are equal or un equal in length. He just lays a rule down next to them and measures them. But to say that Kennedy and Nixon are equal, the social scientist must take a political or ideological position. Any such investigation is, as the French used to say, guilty. That is, it is inseparable from some ideological stance. How will we as students know what ideological stance to take?

You are correct. And what is more, Smith and Marx and Durkheim and Freud and Weber cannot answer that question for you. I will give you an answer, by telling you another story, this time from my years teaching at Columbia. In 1968, as some of you will recall, the students occupied several buildings and brought the university to a screeching halt for two weeks. The next semester, I was teaching a course in which I was anguishing over my inability to find, in the text of Kant's GROUNDWORK OF THE METAPHYICS OF MORALS, an absolutely valid a priori proof of the universal validity of the fundamental moral principle, the categorical Imperative. After class one day, one of the students came up to talk to me. He was one of the SDS students who had seized the buildings, and I knew that he was active off campus in union organizing. 'Why are you so concerned about finding that argument?' he asked. Well, I said, if I cannot find such an argument, how will I know what to do? He looked at me as one looks at a very young child, and replied, 'First you have to decide which side you are on. Then you will be able to figure out what you ought to do.'

At the time, I thought this was a big cop-out, but as the years have passed, I have realized the wisdom in what he said. I want [I now said] to direct these next remarks to the undergraduates who are here today. [There were maybe two dozen among the 200 people at the lunch]. As you complete your studies and go out into the world, you have a decision to make. You must decide who your comrades are going to be in life's struggles. You must decide which side you are on. Will you side with the oppressed, or with the oppressors? Will you side with the exploiters, or with the exploited? Will you side with the occupiers, or with the occupied? I cannot make that decision for you, and neither can Smith and Marx and Durkheim and Freud and Weber. All I can do is to promise you that if you side with the oppressed, with the exploited, with the occupied, then the next time you decide to seize a building, I will be with you.

There is one more matter about which I feel I must say something. I refer to the controversy to which Richard Tuck referred in his opening remarks this morning [ed. Tuck, the current head of Social Studies and a splendid man, had said a few words about the controversy during his welcoming speech, distancing himself from the content of Peretz's statements.] I have anguished a great deal about this matter, at one point uncertain whether I ought even to attend the celebration. If I were a religious man, I could let my bible fall open at random, relying on The Lord to guide me to a chapter and verse in which I might find some wisdom. But since I am an atheist, that course was not open to me. So I did the next best thing. I took down my copy of Volume One of Das Kapital. As I turned the old, familiar pages, covered with my underlinings and notes, my eye fell on this famous passage from the great chapter on Money. Since you are all former or present Social Studies students, I am sure you will all recall it. Here is what Marx says.

Because money is the metamorphosed shape of all other commodities, the result of their general alienation, for this reason it is alienable itself without restriction or condition. It reads all prices backwards, and thus, so to say, depicts itself in the bodies of all other commodities, which offer to it the material for the realisation of its own use-value. At the same time the prices, wooing glances cast at money by commodities, define the limits of its convertibility, by pointing to its quantity. Since every commodity, upon becoming money, disappears as a commodity, it is impossible to tell from the money itself, how it got into the hands of its possessor, or what article has been changed into it. Non olet, from whatever source it may come.

Marx assumed that the working men and working women for whom he wrote this book all had a classical education, but since I did not, I was forced to look up the source of the Latin tag, non olet. It seems that in the time of the Emperor Vespasian, the Roman state raised a little extra money by taxing the public urinals. One day, Vespasian sent his son, Titus, to collect the taxes from the urinals. Titus was offended by the task, which he considered beneath him, and when he returned he flung the money at his father's feet. Vespasian looked down with equanimity and remarked languidly, "Pecunia non olet." The money does not stink.

In the realm of higher education, Harvard is an imperial power, so quite naturally it adopts Vespasian's point of view toward the money it accepts, Pecunia non olet. But from its founding, fifty years ago, Social Studies has held itself to a higher standard, and so I would hope that it will reject this money for a scholarship, because pecunia olet. The money stinks.

I, by contrast, think that there is much more than a dime's worth of difference between Kennedy-Johnson on the one hand and Nixon-Lodge on the other--and I marvel that Robert Paul Wolff, now 77, does not think that Medicare matters at all.

And I think that the important thing is not to side with the oppressed as an attitudinal pose but rather to do something to enhance freedom. I side with Keynes against Trotsky:

Trotsky is concerned in these passages with an attitude towards public affairs, not with ultimate aims. He is just exhibiting the temper of the band of brigand-statesmen to whom Action means War, and who are irritated to fury by the atmosphere of sweet reasonableness.... "They smoke Peace where there should be no Peace," Fascists and Bolshevists cry in a chorus, "canting, imbecile emblems of decay, senility, and death, the antithesis of Life and the Life-Force which exist only in the spirit of merciless struggle." If only it was so easy! If only one could accomplish by roaring, whether roaring like a lion or like any sucking dove!

The roaring occupies the first half of Trotsky's book. The second half.... First proposition. The historical process necessitates the change-over to Socialism.... Second proposition. It is unthinkable that this change-over can come about by peaceful argument and voluntary surrender. Except in response to force, the possessing classes will surrender nothing.... Third proposition. Even if, sooner or later, the Labour Party achieve power by constitutional methods, the reactionary parties will at once Proceed to Force.... Fourth proposition. In view of all this, whilst it may be good strategy to aim also at constitutional power, it is silly not to organise on the basis that material force will be the determining factor in the end....

Granted his assumptions, much of Trotsky's argument is, I think, unanswerable. Nothing can be sillier than to play at revolution if that is what he means. But what are his assumptions? He assumes that the moral and intellectual problems of the transformation of Society have been already solved--that a plan exists, and that nothing remains except to put it into operation.... He is so much occupied with means that he forgets to tell us what it is all for. If we pressed him, I suppose he would mention Marx.... Trotsky's book must confirm us in our conviction of the uselessness, the empty-headedness of Force at the present stage of human affairs. Force would settle nothing no more in the Class War than in the Wars of Nations or in the Wars of Religion. An understanding of the historical process, to which Trotsky is so fond of appealing, declares not for, but against, Force at this juncture of things. We lack more than usual a coherent scheme of progress, a tangible ideal. All the political parties alike have their origins in past ideas and not in new ideas and none more conspicuously so than the Marxists. It is not necessary to debate the subtleties of what justifies a man in promoting his gospel by force; for no one has a gospel. The next move is with the head, and fists must wait.

Liveblogging World War II: November 26, 1940

November 26, 1940:

Stalin tries to cement his alliance with Hitler: The German Ambassador in the Soviet Union (Schulenburg) to the German Foreign Office: Molotov asked me to call on him this evening and in the presence of Dekanosov stated the following:

The Soviet Government has studied the contents of the statements of the Reich Foreign Minister in the concluding conversation on November 13 and takes the following stand:

The Soviet Government is prepared to accept the draft of the Four Power Pact which the Reich Foreign Minister outlined in the conversation of November 13, regarding political collaboration and reciprocal economic support subject to the following conditions:

Provided that the German troops are immediately withdrawn from Finland. which, under the compact of 1939, belongs to the Soviet Union's sphere of influence. At the same time the Soviet Union undertakes to ensure peaceful relations with Finland and to protect German economic interests in Finland (export of lumber and nickel).

Provided that within the next few months the security of the Soviet Union in the Straits is assured by the conclusion of a mutual assistance pact between the Soviet Union and Bulgaria, which geographically is situated inside the security zone of the Black Sea boundaries of the Soviet Union, and by the establishment of a base for land and naval forces of the U.S.S.R. within range of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles by means of a long-term lease.

Provided that the area south of Batum and Baku in the general direction of the Persian Gulf is recognized as the center of the aspirations of the Soviet Union.

Provided that Japan renounces her rights to concessions for coal and oil in Northern Sakhalin.

In accordance with the foregoing, the draft of the protocol concerning the delimitation of the spheres of influence as outlined by the Reich Foreign Minister would have to be amended so as to stipulate the focal point of the aspirations of the Soviet Union south of Batum and Baku in the general direction of the Persian Gulf.

Likewise, the draft of the protocol or agreement between Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union with respect to Turkey should be amended so as to guarantee a base for light naval and land forces of the U.S.S.R. On [am] the Bosporus and the Dardanelles by means of a long-term lease, including-in case Turkey declares herself willing to join the Four Power Pact-a guarantee of the independence and of the territory of Turkey by the three countries named.

This protocol should provide that in case Turkey refuses to join the Four Powers, Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union agree to work out and to carry through the required military and diplomatic measures, and a separate agreement to this effect should be concluded.

Furthermore there should be agreement upon:

a) a third secret protocol between Germany and the Soviet Union concerning Finland (see Point 1 above).

a fourth secret protocol between Japan and the Soviet Union concerning the renunciation by Japan of the oil and coal concession in Northern Sakhalin (in return for an adequate compensation).

a fifth secret protocol between Germany, the Soviet Union, and Italy, recognizing that Bulgaria is geographically located inside the security zone of the Black Sea boundaries of the Soviet Union and that it is therefore a political necessity that a mutual assistance pact be concluded between the Soviet Union and Bulgaria, which in no way shall affect the internal regime of Bulgaria, her sovereignty or independence."

In conclusion Molotov stated that the Soviet proposal provided five protocols instead of the two envisaged by the Reich Foreign Minister. He would appreciate a statement of the German view.

November 25, 2010

Michael O'Hare's Limoncello Is Very Good

November 23, 2010

Liveblogging World War II: November 24, 1940

November 24, 1940:

World War II Day-By-Day: Day 451 November 24, 1940: Operation Collar. Convoy ME4 from Britain passes the Straits of Gibraltar bound for Malta and Alexandria (merchant ships SS New Zealand Star, SS Clan Forbes and SS Clan Fraser, escorted by cruisers HMS Manchester and HMS Southampton carrying 1,370 RAF personnel to reinforce the garrison at Malta). Destroyer HMS Hotspur and 4 corvettes join to escort the convoy at Gibraltar. Mediterranean convoys are escorted from Gibraltar to Malta by Admiral Somerville’s Force H and then onwards to Alexandria, Egypt, by Admiral Cunningham’s Mediterranean fleet. Battleships HMS Ramillies and HMS Malaya, cruisers HMS Newcastle, Coventry and Berwick plus 5 destroyers are on their way from Alexandria to pick up the convoy in mid-Mediterranean...

We Need More Health Care Reform

Matthew Yglesias:

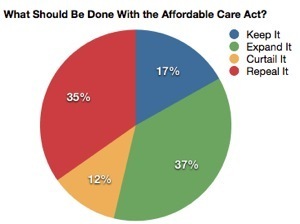

Affordable Care Act Repeal Unlikely, Unpopular: Nobody is head over heels in love with the Affordable Care Act, but McClatchy notes that much of the discontent is from the left and the public constituency for repeal is quite small:

On the side favoring it, 16 percent of registered voters want to let it stand as is. Another 35 percent want to change it to do more. Among groups with pluralities who want to expand it: women, minorities, people younger than 45, Democrats, liberals, Northeasterners and those making less than $50,000 a year. Lining up against the law, 11 percent want to amend it to rein it in. Another 33 percent want to repeal it. Among groups with pluralities favoring repeal: men, whites, those older than 45, those making more than $50,000 annually, conservatives, Republicans and tea party supporters.

Nothing surprising about the demographics here or the outcome. If you polled me on this, I’d count myself as someone who wants to expand the law. To give a more nuanced view, though, I think there’s room for both expansion and curtailment. What’s more, even though few in Congress want to hear it the reality is that we need to do more health reform. Much more. The cost/quality situation is nowhere near good enough. What’s needed, in political terms, is some kind of credible escape hatch through which conservative politicians can engage with changing health care law in some way other than demanding repeal. This is what I think is promising about the Scott Brown / Ron Wyden state waiver initiative.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers