J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2137

December 15, 2010

We Are Lucky to Have Shirley Sherrod Among Us

Kathy Politt:

Comment is free | guardian.co.uk: For courage and grace under truly nonsensical fire, Shirley Sherrod, former Georgia state director of rural development for the US Department of Agriculture, is my hero of the year.

On 19 July, rightwing blogger Andrew Breitbart released video excerpts of a speech Sherrod, who is black, had given atan NAACP event in March, in which she supposedly boasted that she had dragged her feet in helping a white farmer. Within moments the story went viral – and vicious – throughout the conservative media; Ben Jealous, head of the organisation, tweeted his disapproval of Sherrod; by the end of the day, agriculture secretary Tom Vilsack had fired her.

In fact, the excerpts completely misrepresented the speech in which Sherrod movingly described feelings she had had to overcome (and did overcome) when in 1986 a white farmer, Roger Spooner, had come to her for help saving his farm. Given that Sherrod's father had been murdered when she was 17 years old by a white person who was never prosecuted and that a cross had soon after been burned in front of the family home, perhaps she had a lot to get over. The next day, the now very elderly Roger and Eloise Spooner stepped forward to defend Sherrod for having saved their land. Obama called and Vilsack offered to give her back her job. Sherrod declined.

The real Shirley Sherrod has been a well-known civil rights activist in Georgia since the late 60s. What does it say about the US that a hack like Breitbart can destroy a decades-long career in one day? That the head of the nation's premier civil rights organisation is so ignorant of the history of his own movement? That the administration of the first black president is so fearful of the rightwing media that it didn't even take a day to think it over before jumping on their absurd bandwagon?

In a just world, Vilsack would have been fired and Sherrod would be sitting at his desk. In this world, she has the satisfaction that, of all the people involved in this sordid tale, she and those ancient white farmers kept their heads, their dignity and their historical memory intact.

December 14, 2010

DeLong Smackdown Watch: Incoherence Edition

Tyler Cowen writes:

Marginal Revolution: Brain teasers from monetary theory and Scott Sumner: not everyone will understand... DeLong on Scott Sumner...

I take it that this is a polite admonition tyo me to figure out how to rewrite my post...

Whatever the Economist Is Paying Will Wilkinson to Blog for Its "Democracy in America" Feature...

Liveblogging World War II: December 14, 1940

In the Western Desert, British troops of the 7th Armored Brigade cross over into Libya as Operation Compass continues.

Bond Markets Show a Welcome Decline in Fear and Panic

Martin Wolf:

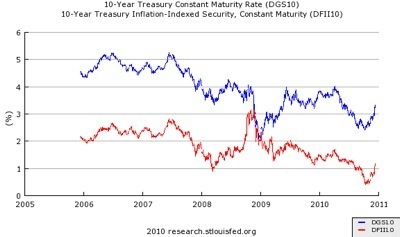

Why rising rates are good news: Terrified by irresponsible fiscal and monetary policies, the bond market vigilantes are out in force. So rose the cry, as rates on government bonds jumped last week. Alas for the panic-mongers, this glib story is nonsense. What is happening is a move towards normalisation. That is excellent news. Policy is working. That does not mean it could not be improved. But what is astonishing is not how high nominal and real interest rates have become, but how low they remain. They are likely to rise substantially if and when less abnormal conditions arrive.

What has happened? Between November 30 and December 13 2010, the yield on 10-year US government bonds jumped by 0.49 percentage points.... Are these jumps significant? No. In the case of the US, rates are back where they were in June 2010, before the marked fall in optimism about economic prospects....

To understand what is going on, we need to distinguish the role of shifts in real interest rates from that of shifts in inflation expectations. Fortunately, inflation-indexed bonds allow us to do just that. In the US, the recent rise in nominal rates is explained almost entirely by the rise in the real rate, not by a rise in implied inflation expectations. To be precise, the rise in real rates turns out to explain 76 per cent of the jump from November 30 2010 and 83 per cent of the jump from November 4 2010.... Do these jumps in long-term interest rates mean that the Fed’s quantitative easing programme has failed? Absolutely not. The Fed’s aim is to make rates lower than they would otherwise be and so raise economic growth and eliminate any threat of deflation. Rates are still remarkably low. They are rising because of a jump in real rates that almost certainly reflects improved prospects for growth. I would imagine that the Fed is pleased with the picture it sees before it....

Are long-term interest rates likely to rise still further? Definitely....

In all, what has happened in bond markets is encouraging. Rates are rising, as depression psychology dwindles. With luck, the recovery is going to take hold. Hurrah!

Scott Sumner Plumps for Nominal GDP Targeting--of a Sort

It is a very interesting article. The first half of it is the best conservative argument for nominal GDP targeting that I have ever seen. Then the going gets somewhat weird, for it is a somewhat strange form of nominal GDP targeting he ultimately calls for...

The start of his essay:

Money Rules: Once the devastating costs of deflation are acknowledged, one can no longer imagine an earlier age when the dollar was “as good as gold.” A gold standard stabilizes the price of one good, gold itself, at the cost of allowing instability in the overall price level.... Nor can we avoid the pitfalls of previous gold-standard regimes by getting government out of the picture. If governments did not hold gold reserves for monetary purposes, the value of gold would be even more closely tied to fluctuations in the industrial demand for the metal. In recent years, almost all metals prices have become highly unstable, as rapid industrialization in Asia has pushed up their prices relative to those of other goods. Fixing the nominal price of gold will not lead to price stability.

For better or worse, conservatives need to acknowledge that we live in a fiat-money world, and we need to figure out a way of managing paper money... we can’t dodge the hard questions of macroeconomics and blithely assert that we oppose the Fed’s “meddling” in the economy. There is no laissez faire in fiat money. If the Fed holds the money supply constant, it will be changing the interest rate and the price level. And if it holds interest rates constant, it loses control over the price level and money supply. As a result, many economists now favor some sort of inflation-targeting regime.... But inflation targeting has several defects that in my view make nominal income (or GDP) stabilization a better goal.

One well-known argument against inflation targeting is that there are times when price-level fluctuations are desirable... during a productivity boom, it might be better to have a mild deflation in order to prevent labor markets from overheating. Conversely, a negative supply shock ought to make inflation rise: We don’t want to force all non-energy prices to fall to make up for an oil embargo.

Most of the problems that are believed to flow from an unstable price level actually result from nominal-income instability... Borrowers almost always have trouble repaying debts when nominal income comes in much lower than was expected when the debts were contracted. Some people overlook this problem because they focus on the most spectacular debt problems.... But those cases are merely the tip of the iceberg; the sort of systemic debt problem now faced by the Western world goes far beyond these isolated cases, and can be explained only by the fall in nominal income.

Would my proposal for NGDP targeting merely bail out reckless borrowers? No; I am asking the Fed to provide a stable policy environment for the negotiation of wage and debt contracts. Right now, a sudden fall in NGDP growth tends to lead to mass unemployment, lower profits, and sharply higher debt defaults. An unexpectedly large increase in NGDP would cause problems of its own when the stimulative effects wore off. In fact, it is our current policy that is unfair....

If the Fed decides to target NGDP, it will need to choose an optimal growth rate.... There are two NGDP target paths that might be politically acceptable... 3 percent... 5 percent.... The Fed clearly thought that 5 percent nominal growth was fine during the Great Moderation, but the near-zero nominal growth over the past few years has had a disastrous impact, much worse than it would have, had it been expected and factored into wage and debt contracts negotiated in earlier years...

Then, however, things in the essay do get somewhat weird, for it is a somewhat strange form of nominal GDP targeting he ultimately calls for.

It is not that the Federal Reserve buys and sells bonds (government and perhaps private) for cash in order to try to get the money stock and other variables to levels that lead its forecasters to predict that nominal GDP will grow at, say, 5% per year.

Instead, Scott writes that:

[t]he Fed would simply define the dollar as a given fraction of 12- or 24-month forward nominal GDP, and make dollars convertible into futures contracts at the target price.... The public, not policymakers in Washington, would determine the level of the money supply and interest rates most consistent with a stable economy...

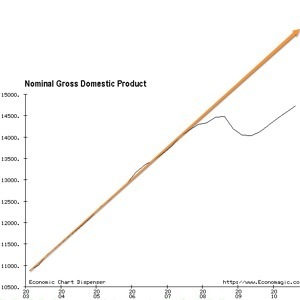

As I understand Scott's proposal, it is this: Nominal GDP in the fourth quarter of 2007 was $14.291 trillion. A 5% growth rate from that base would give us a value of $17.455 trillion for the fourth quarter of 2011. Add on another 3% for the average short-term nominal interest rate we would like to see, and we have $18.153 trillion. Therefore the Federal Reserve would, today, announce that it stands ready to buy and sell dollar deposits to qualified customers at a price of $1 = 1/18,155,000,000,000 of 2011Q4 GDP.

If investors thought that nominal GDP in the fourth quarter of 2011 was likely to be lower than $18.15 trillion, they would take the Fed up on its offer: demand the cash now, pay off the contract in a year by then paying 1/18,155,000,000,000 of 2011Q4 GDP, and (hopefully, if they were right) make money--thus the money stock would increase. If investors thought that nominal GDP in the fourth quarter of 2011 was likely to be greater than $18.155 trillion, they would take the Fed up on its offer: give cash to the Fed now, collect the contract in a year by receiving 1/18,155,000,000,000 of 2011Q4 GDP, and (hopefully, if they were right) make money--thus the money stock would fall.

If nominal GDP were expected to fall, the Federal Reserve would be shoveling money out the door at negative expected nominal interest rates. If his scheme were applied today it would be quantitative easing on a pan-galactic scale, as everybody would run to the Fed with bonds to use as collateral for their promises to pay the expected futures contract in a year in exchange for the cash now.

The Federal Reserve would then become truly the lender of not just last but first resort. Why would anybody borrow on the private market even at 0% per year when they could borrow from the Fed at -3%/year? Savers would simply hold cash rather than try to match the terms that the Fed was offering borrowers. Borrowing firms would borrow from the Fed exclusively. The Fed would thus create a wedge between the minimum nominal interest rate that savers would accept (zero, determined by the alternative of stuffing cash in your mattress) and the nominal interest rate open to borrowers.

I see how this would solve a monetarist downturn--a shortage of liquid cash money projected to lead to nominal GDP below its target. Once arbitrage had kicked in there would be no shortage of cash money.

I see how this would solve a Keynesian downturn--a shortage of savings vehicles that means that balancing savings and investment at full employment requires a nominal interest rate of -3%, which the zero-bound keeps you from getting to. The Fed would lend to all comers at a nominal interest rate of -3%.

I cannot quite see how this would solve a Minskyite downturn--a flight to quality because of a collapse in the market's risk tolerance and a shortage of safe assets. But perhaps this is because I am a bear of too little brain to figure it out during the Econ 1 final when the GSIs are glowering at me because I am supposed to be outlining the answers for the essay questions...

Scott goes on, anticipating that implementation of his proposal would bring the New Jerusalem: "And the building of the wall of it was of jasper: and the city was pure gold, like unto clear glass. And the foundations of the wall of the city were garnished with all manner of precious stones. The first foundation was jasper; the second, sapphire; the third, a chalcedony; the fourth, an emerald; 20: The fifth, sardonyx; the sixth, sardius; the seventh, chrysolite; the eighth, beryl; the ninth, a topaz; the tenth, a chrysoprasus; the eleventh, a jacinth; the twelfth, an amethyst":

This sort of policy regime addresses many of the liberal arguments for big government. Right now conservatives don’t have good counterarguments to Paul Krugman’s insistence that all the laws of economics go out the window when we are in a “depression.” Classical economics assumes full employment; how credible are classical arguments against federal job-creation schemes when unemployment is 9.8 percent? Yes, government intervention doesn’t even work very well when there is economic slack. But with NGDP futures targeting, there is no respectable argument for fiscal stimulus, as the money supply would already be set at the level expected to produce the desired level of future nominal spending.

In a world of NGDP futures targeting, liberals would no longer be able to mock those who invoke Say’s Law (supply creates its own demand). It would be transparently obvious that any auto demand created by a bailout of GM would be at the expense of less demand in some other sector of the economy. Nor would the Washington elites be able to intimidate people into bailing out the big banks by pointing to the specter of an economic depression. Banks would fail, but the money supply would adjust so that expected future nominal spending continued to remain on target. Creative destruction could do what it’s supposed to do, with jobs lost in declining industries being offset by jobs gained in creative new enterprises.

There are two types of conservatism. One is pessimistic, resentful, dismissive of any claims of progress in governance. It relies on nostalgia for a mythical golden age, before big government ruined everything. It is scornful of intellectual inquiry into new policy approaches. Nominal GDP futures targeting is part of an optimistic, forward-looking conservatism; it is progressive in the best sense of the term. It is based on time-tested conservative principles, such as the fact that markets can set prices and quantities better than government can, but also builds on the serious academic work of scholars such as Milton Friedman, who understood the devastating effects of a serious plunge in nominal output. There’s no going back, but we can build a monetary regime that undercuts the liberal arguments for big government while providing an economic environment where capitalism can flourish.

I am somewhat skeptical. It seems to me that sensible fiscal policy might be better than mega-TARP helicopter drops to bankers under some circumstances. And people even quarrel over the construction of the New Jerusalem. Wikipedia:

Revelation lacks a list of the names of the Twelve Apostles, and does not describe which name is inscribed on which foundation stone, or if all of the names are inscribed on all of the foundation stones, so that aspect of the arrangement is open to speculation. The layout of the precious stones is contested. All of the precious stones could adorn each foundation stone, either in layers or mixed together some other way, or just one unique type of stone could adorn each separate foundation stone...

Yes, of Course Nick Clegg Should Blow Up Britain's Conservative Government and Send Miliband to Kiss the Queen's Hands. Why Do You Ask?

Nick Clegg is on the road to winning the contest to be the worst British politician since Ramsey MacDonald.

Philip Stephens:

Britain’s coalition badly needs a Plan B: The uproar over higher education funding has exposed what was always going to be the coalition’s weak point. Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats – the junior partner – have found themselves serving as the lightning rod for public anger at policies framed by David Cameron’s Conservatives. The steep rise in student tuition fees was a Conservative choice. You would not think so from the public furore. Mr Cameron, who has a habit of putting himself above the fray at awkward moments, has artfully left Mr Clegg to absorb the opprobrium. Voters could be forgiven for thinking that the Lib Dem leader had been the architect of a policy that he and his party had roundly denounced during the election campaign.... There will be other collisions. The coalition agreement promised Mr Clegg’s Lib Dems an end to top-down reorganisations of the health service. Yet Andrew Lansley, the Tory health secretary, is now pushing through the most radical shake-up since the inception of the NHS....

It is the economy that will make the political weather during the first half of 2011... things will be grim.... It is hard to see where the growth will come from. Value added tax is set to rise in January. The Bank of England’s suspension, in effect, of its 2 per cent inflation target will see a further squeeze on household incomes as prices outpace wages. Swingeing spending cuts will see the public sector shed programmes and jobs ahead of the new financial year.

The government’s answer is that exports and investment will do the trick. The very radicalism of its planned fiscal retrenchment will persuade business that better times are around the corner.

Not everyone is so confident. A confidential paper circulating in Downing Street suggests the government should consider in advance if not a fully worked up “Plan B” then at least a series of possible stimulus measures.... [M]ore quantitative easing by the Bank... lend directly to business through buying commercial as well as government bonds... accelerate spending in infrastructure.... Tax cuts would be another option....

The fundamentalists... may be proved right. As in the 1930s, they have the Bank governor on their side, though that is hardly a recommendation. I have not come across many practical economists who share their confidence....

The government really should have a Plan B. Mr Clegg might consider whether he also needs a Plan C.

Nick Rowe on Why the Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle Is Arrant Nonesense

As Milton Friedman once said, Friedrich von Hayek was a great economist, but his contributions definitely did not lie in business cycle theory.

Nick Rowe:

Worthwhile Canadian Initiative: Money, Barter, and Recalculation: The [economic] calculation problem doesn't solve itself. It takes people to solve it. The price system helps them solve it. Monetary exchange helps them solve it. But it isn't easy to solve.... And if technology, resources, and preferences are changing as well, people have to keep re-solving it. That's what I take to be the [economic] re-calculation problem.

But that re-calculation is happening all the time. What's it got to do with recessions?

The answer, as Nick says very well, is "absolutely nothing":

Sure, sometimes a really big real shock comes... and it takes a lot more re-calculation than it normally does.... [A] financial crisis isn't... a change in the underlying tastes, technology, and resources.... But... it too would require a re-calculation. And maybe output would fall while we are trying to figure out how to re-solve the economic problem. Maybe even employment would fall too:

Hang on guys, don't commit to doing anything quite yet, while I try and figure out where you should best be working now that everything's changed...

But I just can't buy it as a full story of recessions. It's the general glut thing that's missing. Stuff gets easier to buy in a recession, and stuff gets harder to sell.... What makes a recession a recession, and something more than a bad harvest, or a re-calculation, is that most goods, and most labour, gets harder to sell and easier to buy. And I really want to call that an excess demand for money. Because it is money we are selling stuff for, and it is money we are buying stuff with. And... I've also got a theory... which says that an excess demand for money will cause a drop in output and employment, and an excess supply of goods and labour...

Why Oh Why Can't We Have a Better Press Corps? (Sewell Chan of the New York Times Edition)

That Thomas Hoenig has consistently overestimated the impact of Fed policy on the inflation rate throughout his tenure at the Kansas City Fed does not mean that he is wrong today. But it is something that a reporter like Sewell Chan needs to put his article. Chan's failure to do so breaks his contract with his readers:

Hoenig, Contrarian at the Fed, Keeps Wary Eye on History: As the lone dissenter on the Federal Reserve committee that sets interest rates, Mr. Hoenig, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, has been a persistent skeptic of just about everything the Fed’s chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, has done to try to stimulate the flagging recovery. Mr. Hoenig’s latest, loudest objections, aimed at the Fed’s risky $600 billion infusion into the markets to reinvigorate the economy, have made him a champion of the Fed’s critics in Congress, on Wall Street and among business leaders, who, like Mr. Hoenig, fear that the central bank is risking runaway inflation, asset bubbles and a weakened dollar.... To him, Mr. Bernanke’s plan is “a dangerous gamble” and “a bargain with the devil,” strong words that have rankled some officials of the Fed, where dissent is tolerated but not celebrated....

Why oh why can't we have a better press corps?

December 13, 2010

What Does an Unmanaged Macroeconomy Look Like?

In some very nice musings about Lawrence Summers's farewell address, Greg Ip commits one misstep when he writes that:

What will scholars’ verdict of Mr Summers’ contribution be?... The pessimistic view... macroeconomic activism failed because its success in the decades before the crisis sowed the seeds of ever more risk-taking and complacency...

It is certainly possible that the relative macroeconomic calm of what we used to call the "Great Moderation" from 1985-2005 played a material role in setting the stage for our current volatility and distress. But in the larger sweep of history, even our current volatility and distress has been quite effectively handled and managed--at least compared to what went on back before the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve took on the mission to attempt and handle and manage the macroeconomy.

We can see this if we take a look back and ask the question: what does an economy without effective macroeconomic regulation look like?

We do not have all that many examples. Britain's Bank of England started regulating the macroeconomy in response to the industrial business cycle back in 1825. The Bank of France was not far behind. Almost as soon as a country had a capital-intensive industrial sector capable of generating a modern business cycle, it had a central bank to stabilize its macroeconomy.

The U.S. was an exception. It lost its proto-central bank to Andrew Jackson in the 1830s. It did not acquire a central bank until 1913--and the central bank had no clue what to do in a recession after the death of Benjamin Strong in 1928. The pre-World War II U.S. was as close to an economy without effective macroeconomic regulation as we have--and even there we have occasional monetary and banking policy conducted by the pickup central banks that were the House of Morgan in 1907 and the Belmont-Morgan syndicate in 1895. It was the passage of the Employment Act of 1946 that marked the start of systematic stabilization policy in the United States.

And, at least from the perspective of the metric that is the non-farm unemployment rate--the agricultural sector does not have an industrial business cycle, after all--there is no evidence that macroeconomic management has not been vastly better than the alternative.

Greg Ip:

American economic policy: The legacy of Larry Summerst: FOR two years the Obama Administration’s economic policy has been caricatured from the right as an invasive expansion of government and from the left as a cowardly capitulation to Wall Street free market fundamentalism. How can it be both things at once? It helps to understand the philosophy of the man who most embodies that policy, Larry Summers, who today delivered perhaps his final public speech as Barack Obama’s National Economic Council director. The "Summers Doctrine" fuses microeconomic laissez faire with macroeconomic activism. Markets should allocate capital, labour and ideas without interference, but sometimes markets go haywire, and must be counteracted forcefully by government.

The most liberal economists concede the intrinsic superiority of markets in allocating real economic resources but many make an exception for financial markets. Mr Summers doesn’t, and that’s what critics from the left most hold against him. In his tenure in the Clinton Administration he championed the repeal of Glass-Steagall and blocked Brooksley Born’s efforts to regulate over-the-counter derivatives. Mr Summers holds regulators in low esteem.... He brought this view with him to the White House, battling efforts on the Hill and inside the Administration to nationalise banks, corral bankers’ pay, or curb derivatives and trading activity.

Yet Mr Summers’ mistrust of government is not the same as a trust in markets.... Mr Summers supplemented his academic appreciation of markets’ limitations with real-world experience in the Clinton Administration. The Mexican and east Asian financial crises demonstrated to horrific effect how markets could rapidly go from complacency to panic. Mr Summers sums up the lesson with a line he attributes to former Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo: “Markets overreact—and that means policy has to overreact.” Crises call for the financial equivalent of the “Powell Doctrine”: the application of overwhelming monetary force so that market participants have no doubt about the ability and will of policymakers. Austrian economists fret that this simply sows moral hazard; to Mr Summers, this was precisely the point: with the government providing insurance against catastrophe, investors could take more risks, generating more innovation, more growth, and more welfare....

When Mr Summers reflected on his two years in the White House in today’s speech....

Scholars … will continue to debate just how close the American financial system and economy came to all-out collapse in the six months between September of 2008 and April of 2009… Had it not been for President Obama’s willingness to support a sufficiently aggressive response … I have little doubt that we would be looking at a vastly different world today.

He framed the recent tax deal Mr Obama negotiated with Republicans the same way. Excluding the extension of expiring tax provisions, it contains about $280 billion of new stimulus. Only by the standards of the last few years is that less than overwhelming. Mr Summers went on:

It is right and necessary for government to counteract private sector deleveraging. … Even with our deficits, the amount of extra debt is less than the amount of reduced borrowing in the private sector… the recent tax agreement … averts what could have been a serious collapse in purchasing power and adds far more fiscal support than most observers thought politically possible.

What will scholars’ verdict of Mr Summers’ contribution be?... The optimistic view is that the economy is now in a sustained, though restrained, recovery that will prove Mr Summers right. The pessimistic view takes two paths. One follows Ireland, a country that applied more Powell doctrine than it could afford; by guaranteeing all its banks’ liabilities it has undermined the solvency of the sovereign. This seems unlikely. The other follows Japan into a trap of stagflation and deflation, one that Mr Summers is unwilling to dismiss: “The risks of deflation or stagnation in the United States exceed the risks of uncontrolled growth or high inflation.” If that is indeed America's fate, we may conclude that macroeconomic activism failed because its success in the decades before the crisis sowed the seeds of ever more risk-taking and complacency...

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers