J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 2131

December 27, 2010

Paul Krugman and Robin Wells Are Really Unhappy with How Obama Has Played His Hand...

PK and RW:

Where Do We Go from Here? : [D]espite warnings from many economists (ourselves included) that the stimulus package that resulted was much too small, Obama engaged in premature triumphalism. In February 2009, he said of the plan:

It is the right size, it is the right scope. Broadly speaking it has the right priorities to create jobs that will jump-start our economy and transform it for the twenty-first century.

The only thing missing was a “Mission Accomplished” banner.

Worse, the administration seemed unable to change its line once it became clear that the program was, in fact, inadequate. Progressives kept waiting for the moment when Obama would say something like “My predecessor left the economy in even worse shape than we realized—it’s time for further action.” That moment never came. Instead, officials kept insisting that the recovery was on track.... After the midterms, leading Democratic strategists blasted the administration for being tone-deaf: “A metaphor about a car in the ditch when people are in trouble and angry about the abuse of Wall Street, it’s just out of touch with what’s going on,” declared the pollster Stan Greenberg, while James Carville asked, “What were they thinking?” A better political strategy, said Carville, could have limited Democratic losses in the House to thirty seats, but the administration remained weirdly passive right through to election day.

The same passivity was visible on other fronts: the administration did nothing as its mortgage modification program degenerated into a subject of derision; it did nothing to address public anger over Wall Street bailouts; it dithered in the face of Chinese currency manipulation; it hesitated and prevaricated for weeks after the Gulf oil spill. The administration’s political strategy seemed to boil down to sitting around and waiting for the economy to improve.

Now the Republicans control the House and have effective blocking power in the Senate. And all indications are that they are ready and willing to use this position to deny the Obama administration any achievements it could point to in 2012.... Most telling of all is the recent furious, coordinated assault on Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve. Until that assault began, the possibility of “quantitative easing” (purchasing bonds in an attempt to reduce long-term interest rates) by the Fed had been widely viewed as the conservative alternative to fiscal stimulus. The Fed would take action to reduce interest rates and thereby promote private spending. As many have pointed out, the Fed’s current approach is very much in line with the policy prescriptions of Milton Friedman, the patron saint of conservative economics. Indeed, in 1998, when Japan was suffering economic difficulties very similar to those we face now, Friedman urged the Bank of Japan to adopt what amounted to a policy of quantitative easing. But when the Fed finally announced a modest program of quantitative easing on November 3, it was rocked back by outraged demands from Republicans—in the company of China and Germany, two countries that through their own economic policies are thwarting the global economic recovery in the Eurozone and the US—to immediately cease and desist. Moreover, key Republicans in both the Senate and the House demanded that the Fed abandon any effort to promote employment and limit its mandate to price stability. The budget expert Stan Collender, with a sharp sense of realpolitik, anticipated the Republican “scorched economy” strategy back in August: “Ben Bernanke may have painted a big bullseye on the Federal Reserve,” he wrote on his blog Capital Gains and Games. He went on to say:

The same political pressure that has brought fiscal policy to a standstill in Washington is very likely to be applied to the Fed if it decides to move forward. With Republican policymakers seeing economic hardship as the path to election glory this November, there is every reason to expect that the GOP will be equally as opposed to any actions taken by the Federal Reserve that would make the economy better, and that Republicans will openly and virulently criticize the Fed for even thinking about it. The criticism is likely to come both before any action is taken to try to stop it from happening and afterwards to make the Fed think twice about doing more. This will come in spite of the fact that, unlike fiscal policy changes, the actions the Fed is considering will not increase the budget deficit. The deficit has never really been the real issue; it has always been subterfuge and an easy and convenient way to build opposition to the White House’s efforts to deal with the economy.

Thus the Democrats must begin by facing up to the reality of an uphill struggle. The historic opportunity of 2008 has been squandered.... Democrats... can’t count on the economy to propel Obama to reelection—in part because Republicans, whatever they claim or actually believe, will do all they can to keep the economy depressed. Nor can they count on Obama himself to lead a comeback. In a dispiriting 60 Minutes interview given after the midterms, he actually seemed to accept Republican smears—blaming himself, not the GOP, for the failure to “maintain the kind of tone that says we can disagree without being disagreeable.” And it’s truly astonishing that as corporate profits hit new records despite mass unemployment, Obama apparently takes seriously accusations that his administration is antibusiness. Even if Obama were suddenly to find an inner FDR, would anyone notice? His aloofness has become so indelibly registered in voters’ minds that if he tried to change style—even if he wanted to, a big “if”—this would immediately come across as opportunistic...

December 26, 2010

Why Oh Why Can't We Have a Better Press Corps? (New York Times Abuses History Edition)

Margaret MacMillan:

The War to End All Wars Is Finally Over: In truth, the reparations, as the name suggests, were not intended as a punishment. They were meant to repair the damage done, mainly to Belgium and France, by the German invasion and subsequent four years of fighting. They would also help the Allies pay off huge loans they had taken to finance the war, mainly from the United States. At the Paris peace talks of 1919, President Woodrow Wilson was very clear that there should be no punitive fines on the losers, only legitimate costs. The other major statesmen in Paris, Prime Ministers David Lloyd George of Britain and Georges Clemenceau of France, reluctantly agreed, and Germany equally reluctantly signed the treaty...

John Maynard Keynes's view of the same:

: The subtlest sophisters and most hypocritical draftsmen were set to work, and produced many ingenious exercises which might have deceived for more than an hour a cleverer man than the President.... Instead of giving Danzig to Poland, the Treaty establishes Danzig as a "Free" City, but includes this "Free" City within the Polish Customs frontier, entrusts to Poland the control of the river and railway system, and provides that:

the Polish Government shall undertake the conduct of the foreign relations of the Free City of Danzig as well as the diplomatic protection of citizens of that city when abroad....

Such instances could be multiplied. The honest and intelligible purpose of French policy, to limit the population of Germany and weaken her economic system, is clothed, for the President's sake, in the august language of freedom and international equality.

But perhaps the most decisive moment, in the disintegration of the President's moral position and the clouding of his mind, was when at last, to the dismay of his advisers, he allowed himself to be persuaded that the expenditure of the Allied Governments on pensions and separation allowances could be fairly regarded as:

damage done to the civilian population of the Allied and Associated Powers by German aggression by land, by sea, and from the air

in a sense in which the other expenses of the war could not be so regarded. It was a long theological struggle in which, after the rejection of many different arguments, the President finally capitulated before a masterpiece of the sophist's art....

[T]he President was set. His arms and legs had been spliced by the surgeons to a certain posture, and they must be broken again before they could be altered. To his horror, Mr. Lloyd George, desiring at the last moment all the moderation he dared, discovered that he could not in five days persuade the President of error in what it had taken five months to prove to him to be just and right. After all, it was harder to de-bamboozle this old Presbyterian than it had been to bamboozle him...

McMillan could honorably write--and the Times could honorably publish--a piece arguing that Keynes's belief that reparations were in large part punitive was wrong. She cannot honorably write--and it cannot honorably publish--a piece that denies that there is an issue here.

Why oh why can't we have a better press corps?

Econ 1: Fall 2010: U.C. Berkeley: September 29 Economic Growth Lecture

20100929: Econ 1: Fall 2010: U.C. Berkeley: September 29 Economic Growth Lecture:

Thank You For Taking the Midterm: Let me thank you all for taking next Monday's midterm. I know--it is way too early to be proper midterm. The problem is that I need it as an instructor reality-check device.

I stand up here and lecture at you. There are 620 of you. I cannot read your faces well enough to figure out what you are getting and what you are not. I have little clue right now whether my lectures are over most of your heads, or are mind-numbingly slow.

One reason that I lecture--even though I have little clue right now as to whether I am lecturing at the right pace--is that back in the Middle Ages a book cost the same share of average incomes as $50,000 is today. Look at a book. Think that if you were in the Middle Ages--well, you would probably be illiterate. If you were in the Middle Ages and were literate you would probably regard a book kind of like Southern Californians regard a BMW convertible. Students could not really afford books--at least, not many.

Suppose you were a student at the University of Naples in the 12th century. Suppose you owed student loans to the moneylender. Suppose you wanted to leave Naples--in order to go visit your parents in their manor near, say, Goslar. You could not--unless you first gave the moneylender your books to hold as a pledge. The idea was that your books were so valuable that you would repay your student loans if the moneylender had your books.

Come Gutenberg and the invention of printing books become cheap. The idea that teachers have to lecture because students cannot afford to buy all the books for the courses goes away. But still the very large lecture--a staple of education back in the days when the books were really, really expensive and what about the only way to get access to the book was for a group of you to get together and hear it read aloud--still continues. It continues for lots of reasons. But since it has lost its initial purpose as the only effective way that you can learn the words inside the textbook, it is important that our lectures be good. This means that I have to pitch them at the right level. This means that I have to figure out what you have learned. Hence this reality-check midterm, this early reality-check midterm. I really cannot stress enough that it is for my benefit, not yours. So I thank you all for taking it.

Before the Birth of Human Civilization: So, on to the economics of long-run growth.

When did we collectively invent agriculture? When was the Neolithic Revolution? When did we stop being very smart East African Plains Apes with stone tools and actually become civilized people--with fields and firms and domesticated animals and civilizations?

Figure that it happened soon after 10,000 BC.

Dating the invention of agriculture is important, because the invention in agriculture was one of the perhaps four major changes in human life worldwide, at least from an economic point of view. I claim that the first big change was when we learned how to make fire and stone tools. I claim the second was when we developed language: language allows for plannin,g and for collective action of scale much larger than otherwise possible. Otto von Bismarck said: "Fools learn from their own experience. I prefer to learn from other people's experience." Without language it is really difficult to learn from the experience of very many other people: you actually have to see Ogged poke a hornet's nest with a stick. With language it is easy: the cautionary tale of not to do what Ogged did to the hornet's nest can spread rapidly around the entire globe.

I claim that the third big change was the invention of agriculture.

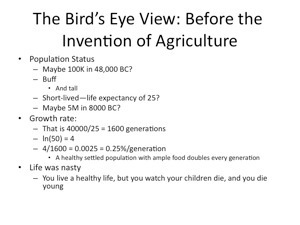

What was human life like in the perhaps 50,000 years--perhaps more, but it is unlikely to be less--between the invention of language on the one hand and the discovery of agriculture? Those were the years when some of us decided to leave our original East African home and venture out across the Red Sea into Arabia, and then from there to pretty much everywhere else in the world (except for Antarctica) over the next 20,000 or 30,000 years?

For one thing, back before 10,000 BC we were pretty buff. Adult males were perhaps 5'8" on average. We were pretty strong too. We had high-exercise lifestyles. We were, however, short lived: life expectancy fracked. Infant mortality was high--babies are fragile things to drag around. And life was pretty dangerous: break a leg and your odds were not good at all; get an infected tusk gore and your odds were very bad.

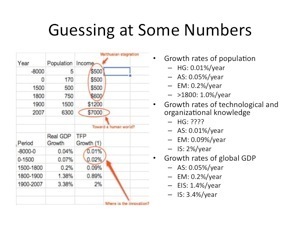

Nevertheless, we rose in population numbers from perhaps 100,000 humans in 48,000 BC to perhaps 5,000,000 worldwide by 8000 BC. That is impressive: a population multiplication by a factor of 50,000 in what is on the evolutionary time scale a remarkably short time. Tell the biologists that a population multiplies 50-fold in 1600 generations and they will be impressed.

On the other hand, we can calculate growth rates. Take the natural log of 50--that is four. Divide that by 1600 generations--that is a population growth rate of 0.25% per generation. That is a population growth rate of 0.01% per year. Look across the average century between 48,000 BC and 8,000 BC: in the average century, for every 100 humans who were alive at the century's beginning there were 101 alive at the century's end.

Contrast that growth rate of 0.01% per year with the current human population growth rate of about 1% per year today, or the growth rate of 3% per year from natural increase alone seen during much of the nineteenth-century temperate-settlement pioneer experience.

That slow population growth rate tells us something pretty important about material standards of living. Think of the British colonist landing on the coast of North America after the plagues, the epidemics, and the wars had decimated the Amerindian population. The rule of thumb is that a healthy settled human population with low female literacy, no effective means of artificial birth control, and ample food doubles every generation. Figure ten pregnancies per potential mother eight of which survive to term six of which survive infancy four of whom reach adulthood. Between 48000 BC and 8000 BC, it wasn't 4 children surviving to adulthood per potential mother but rather 2.005. 1.995 adult children per potential mother that we would expect to see in a settled population with ample food simply do not survive.

That much excess mortality tells us that life was not just short--life expectancy at birth of 25 or so--but brutish. You lived the healthy life. You got lots of exercise hunting and gathering. But you watched perhaps three-quarters of your children die. But you did have pretty much all your teeth--hunters and gatherers had a low-carbohydrate zero refined sugar diet. That is what life was like between 48,000 BC and 8000 BC. You were physically relatively fit. But populations grew at only the most glacial pace--which means that the odds were good that the jaguar got ya.

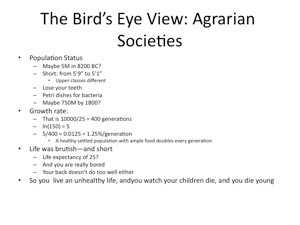

The Agrarian Age: Now let us move on to the world of agriculture that starts in 8000 BC or so: the agrarian society where people figure out:

there are these grasses that have really big seeds

if we plant all these grasses right next to each other in a place that has a lot of water, then

if then we stick around for a while and drive off the birds before they eat the seeds

we will be able to get a lot of our nutrition from these really huge grass seeds--they are quite nourishing

and we won't have to rumble around our hundred square-mile foraging territory: we can just sit at home and each day gather some more grass seeds--especially if we figure out how to dry them so they will keep.

Nowadays we call these seeds by other names. We call them "wheat" "rice," "rye," "barley," "corn," and other things. They still contribute 75% of the calories that human beings eat--some of it in bizarrely-processed forms like the high-fructose corn syrup we drink. With the coming of agriculture your ability to get the calories to maintain your family goes way way up, and the necessity of roaming about the countryside looking for food goes the way way down. Thus you can start building permanent structures. You have much more time to start weaving plant fabrics together with turkey feathers and furs so you can have better clothes to wear.

Inventing agriculture seems like a no-brainer, right? You can build and live in a permanent house so you don’t get as wet. You can weave and stitch better clothes to wear so you don’t get as cold.

But when we dig up skeletons from 100 BC or so, we find that the adult males are not averaging 5'8" any more: they are averaging 5'2". Some people are taller--that Karl who was son of Pippin (called "the short") and of Bertha (called "greatfoot") appears to have been well over six feet tall. On the other hand, this was the guy whom Pope Leo III proclaimed Boss on Christmas Day of the year 800 AD:

Since the title of emperor had become extinct among the Greeks and a woman [Empress Irene] claimed the imperial authority [in the city of Constantinope]...

Pope Leo:

crowned [Karl] with a most precious crown. Then all the faithful Romans, seeing how [Karl] loved the holy Roman church and its vicar and how he defended them, cried out with one voice by the will of God and of St. Peter, the key-bearer of the Kingdom of Heaven, "To Karl, most pious Augustus, crowned by God, great and peace-loving emperor, life and victory." This was said three times before the sacred tomb of blessed Peter the Apostle, with the invocation of many saints, and he was instituted by all as emperor of the Romans. Thereupon, on that same day of the nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ, the most holy bishop and pontiff anointed his most excellent son Karl as king with holy oil...

You can bet that if there was food around, Karl got it--from infancy onward, and before that in utero, for you can bet that Bertha Greatfoot did not go hungry either. The lesson is that the upper classes were different--and with the coming of agriculture there are for the first time real upper classes. Most people after the invention of agriculture, look to have been quite short. Most people look to have been pretty much toothless and eating corn mash by the time they were 40--if they were alive. Everybody looks to have become a wonderful environment for human diseases: think of a bunch of people living together in a village, talking to each other, coughing at each other, drinking each other’s water--the bacteria love it and disease becomes a much bigger deal.

If your adult height is 5'2" for males or 4'11" for females, something has gone very wrong with respect to protein and calcium deprivation. If you were to feed your future children a diet that would make make the boys 5'2" at their adult height, California Child Protective Services would take your children away. But that appears to have been the kind of diet that most human beings seem to have had in the years between 8200 BC and, say, 1800 A.D.

There were, of course, exceptions. The biggest people that the anthropologists have are found so far are in fact the Sioux--the Lakota Indians of the American Great Plains. What is going on? By 1600 a bunch of tame horses imported into America by the Spanish Empire have escaped and run north. These are animals whose ancestors had been tamed and domesticated by humans for 3000. So the Souix can tame them. And all of a sudden the Sioux are no longer dragging their teepees and their other belongings behind them on human or dog-drawn travois as they follow the buffalo. They are riding horses--they can outrun the buffalo. It is, for them, a two-century paradise--until the railroads and the cavalry show up and want to replace the buffalos with cows behind barbed wire, and also want to mine the gold under the Black Hills. The Souix, not surprisingly object and make their objections strongly at places with names like "The Greasy Grass." But they are overwhelmingly outnumbered.

But the Sioux after the coming of the horse and before the coming of the railroad are exceptions. For most humans life is not only short and brutish, but nasty as well--protein and calcium deprivation and tooth decay and epidemic disease wreak their havoc.

Still, human populations grow. Maybe five million people in 8000 BC become 750 million people by 1800. A fifteen-fold multiplication in 10,000 years or 400 generations. That is a population growth rate of 1.25% per generation, or 0.05% per year--fully five times as fast as in the previous hunter-gatherer era. This is still a human population that is in toto close to the margin of "subsistence"--but not quite as close as in the hunter-gatherer age.

On the other hand, life appears to have been a lot less healthy in the biomedical sense. That calcium and protein deprivation hit your bones is obvious from the height of skeletons--and I shudder to think of what it did to your brains. Moreover, life is boring: you no longer have to roam around using your knowledge of plans--this is edible, this will this give me a rash, this will make me sick, this animal we might be able to catch, that animal is called a "grizzly bear" and it is time to run--but instead you do the same thing over and over again, ploughing, sowing, weeding, watering, harvesting, threshing, and so forth. Yesterday we transplanted rice seedlings all day. Today we are going to transplant rice seedlings. And tomorrow we get to transplant rice seedlings. The day after that we get to try to scare off the birds before they eat your rice. And because it is wet rice there are all these nice little worms that like to crawl up through your feet and then live inside you.

The stoop labor is not too good for your back either.

These are all things that lead UCLA professor Jared Diamond to say that the invention of agriculture was probably a mistake.

Yes we do have a lot more people in the world. The carrying capacity for the human race of a world with pre-industrial agriculture technology is about 750 million. That is a lot more than the five million carrying capacity of a world with hunter-gatherer technology. But for the overwhelming majority of the people you were illiterate peasants in the agrarian age, it was probably much more fun and much healthier being a hunter-gatherer back before 8000 BC than being protein-deprived, calcium-deprived, bored out of your skull, infested with hook worm, and suffering chronic plagues in the agrarian age.

The Population Explosion: Come 1500 or so there seems to be somewhat of a change. In the half-century starting in 1500 populations in America collapse: the Spanish land, bringing smallpox and a huge number of other diseases the Amerindians have never seen and have no immunity to with them. But everywhere else between 1500 and 1800 human populations appear to have grown by half--a population growth rate worldwide averaging 0.15% per year, three times as fast as in the previous agrarian age proper.

And since 1800 things have been very different indeed. From 1800 to 1900 our population grew at 0.7% per year. From 1900 to today our population grew at 1.5% per year. There are now nearly seven billion of us on the planet. At the moment we are hoping that the spread of birth control, female literacy, and wealth--together with the fact that while most literate women with opportunities to work outside the home want and are extremely happy to have one or two children, rather few want to have four or more--means that our global population will top out at a peak of ten billion come 2050. But if it does not--if human populations keep growing at 1.5% per year so that by 2100 we have 28 billion and by 2200 we have 127 billion people on the globe, our great-grand children's lives will become very interesting indeed, and not in a way that is likely to be good.

Making Sense of the Pattern: How do we read this broad pattern of human demography? Why were average standards of living so close to "subsistence" for so long? And why are they so different today?

The way to think about humanity once people get the bright idea of agriculture and settlement--and so for the first time it becomes really easy not to forget technologies when the people who invented them die--is more or less like this:

Once we have agriculture and settlement, it becomes rare that human knowledge is lost. You have to look hard for cases--the Dorian Dark Age after the Trojan War in the Aegean, the fall of the Roman Empire in the west--to find them. And human knowledge does improve. Sometimes the improvements are remarkable and marvelous. Between the Tang and the Sung dynasties humans develop via selective breeding strains of rice that allow for double- and then triple-cropping each year. Before 800 AD or so Southern China and Southeast Asia were not very advantageous places to live. It was hard to grow enough food to support a substantial population. But with the coming of multiple-crop wet-rice strains, things change. And so people move from the largely wheat-growing Yellow River valley south, to where a family with a relatively small wet-rice farm can eat their fill. By 1200 there are 50 million people living in and south of the Yangtze in the rice bowl that is southern China.

That is why the history of China before 1000 is a history of northern dynasties and populations--Chin, Han, Tang--while the history of China after 1000 is primarily a history of southern populations--and the capital stays in the north, when it does, to keep an eye on the Mongols.

It is a wonderful thing to develop triple-crop strains of rice. It is a significant technological improvement. It all by itself allows the world population to grow by ten percent or so in the years before 1500--and still feed the 10% higher population at the same standard of living that the lower population had had in 1000.

But such impressive inventions and innovations really are a once-in-two-hundred-years thing. And because such innovations come only once every two centuries, the fact that better-fed people with stronger immune systems have more children meant that human populations expanded and so living standards fell back to "subsistence" rather than having improvements in living standards cumulate. Before 1500 human technological inventiveness tended to produce not better-fed people or richer people, but (save for the upper class) only more people. Figure 0.01% per year as a rough yardstick measure of the pace at which human technological capacity grew.

Since the Industrial Revolution: Today things are very different. Right now the worldwide rate of growth of human technological capabilities looks to be not 0.01% per year but rather 2% per year. This iPad could not have existed ten years ago. It cost something like $500 last April. It will cost $250 next April--when its successor is released. These days we get as much technological progress in a single year as our agrarian society ancestors would get in two centuries. Then it would be a really big deal when you finally figured out a way to attach a horse to a cart in such a way that the weight of the cart was on its shoulders rather than on its neck. It took until 750 AD before people out a plough that was actually any good for ploughing Northern European soils.

Back in the agrarian age each year saw on average one-two thousandth more stuff produced than the previous year. In the 1500-1800 commercial revolution early modern period each year saw on average one-two hundredth more stuff produced than the previous year. The first century of the industrial revolution era--1800-1900--saw perhaps one-seventieth more stuff produced each year than the previous year. But today world global GDP is growing by about one-thirtieth every year. What we humans produce is right now doubling every generation, and has reached a level of about $7000 per person per year.

Now this $7000 bucks per person per year of stuff is not distributed evenly. We have say greater than san Francisco--in which the average material standard of living is close to $50,000 bucks per person per year.We have Somalia where, in a good year, the standard of living is $500 per person per year.

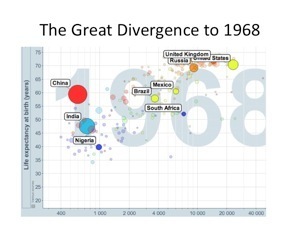

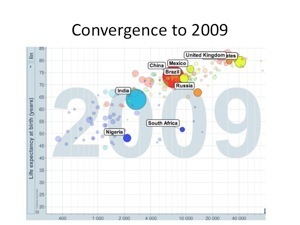

We had in 1968 the most unequal world that humanity had ever seen--or at least humanity had ever seen when some groups of Eastern Africa Plains Apes had developed language and others had not. But there are very good reasons to hope that the world will draw closer together in the future as it has during the past generation and a half. And I think that in the long perspective the most extraordinary thing our great grandchildren will remember about the two past centuries will not be the fact the world has become so unequal but rather that it has become so remarkably rich relative to our past.

Think of it: we had nearly 10,000 years during which humanity was closed to a subsistence agriculture standard of living--a bowl of millet and a bowl of rice every day, maybe a chicken egg once a week, maybe a chicken once a month, and whatever greens you can gather.That was how most people lived most of the time between the invention of agriculture and the industrial revolution.

Our Wealth: Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, conqueror of the Persian Empire, Lord of Asia--the guy who led his soldiers all the way from Greece to Punjab. (At Punjab he turned back because his veteran soldiers started asking him: "just why the frack are we still doing this? I understand revenging the defeats suffered by our ancestors. I understand that Babylon would be a nice push place to live. But here we are by the Jhelum River. Do you really want us to go further? Why?)

Alexander the Great owned two books--the Iliad and the Odyssey. Alexander the Great carried them with him in a gold chest. The books were worth more than the chest.

I, by comparison, have here in this iPad 20000 books instantly accessible for the price of ten steak dinners. And when Google Books becomes properly online I will have access to millions of books. Alexander the Great thought his books were among the most precious things he owned. In book-wealth, I outstrip him by a factor of ten thousand--and will soon outstrip him by a factor of millions.

Back, say, 500 years before Alexander the Great, suppose you wanted a high-status career path. If you were athletic and noble-born you could be a king--even king of a small territory would do because it would give you some armed retainers at your back to help you sack cities. Think Agamemnon son of Atreos, or Akhilleus son of Peleos, or Odysseus son of Laertes. But suppose you weren't a king. Then the best upwardly-mobile career path available to you would probably be to learn how to chant the Odyssey. That would make you a good person to have around in the cold winter nights, and on the warm summer nights too. It could get you a place at the table and a warm place to sleep. Telling the story of the adventures and the homecoming of Odysseus was an economically-valuable service that you could perform:

"What ails you, Polyphemus," said they, '"that you make such a noise,

breaking the stillness of the night, and preventing us from being

able to sleep? Surely no man is carrying off your sheep? Surely no

man is trying to kill you either by fraud or by force?

But Polyphemus shouted to them from inside the cave,

"Noman is killing me by fraud! Noman is killing me by force!"

"Then," said they, "if no man is attacking you, you must be ill;

when Jove makes people ill, there is no help for it, and you had better

pray to your father Neptune."

Then they went away, and I laughed inwardly at the success of my clever stratagem...

But if someone comes up to you today and says: "I know how to chant the Odyssey--and I am going to use this skill to get a high-paying job," we try to let them down gently. We point out that people can buy the audiobook of Ian McKellen chanting the Odyssey for $26.37. We point out that people can buy the Kindle version of Robert Fagles's translation for $12.99--and can download Alexander Pope's translation for free.

Things that would have been regarded in the recent past as valuable and important skills--well, today we are so rich we really don’t notice them at all. That is the change that the industrial revolution. has made.

Why the Industrial Revolution?: Thus the big historical question is: what happened after 1800, and even more so after 1900, that made what we call the industrial revolution? It is the fourth of the big changes in how humanity has lived--along with the invention of agriculture, the development of language, and the invention of stone tools and of fire.

The answer to "what happened" is not "the market economy happened.: Ancient Greece had the market economy. Sung China had the market economy. Neither had the explosion of the economic growth we have seen.

The answer might be "limited government." After 1500, for the first time ever, we have governments that are able to promise that they won’t steal your stuff when they feel like it and to actually carry through on those promises. Before 1500 if had stuff and if you wanted to keep it, the only way to be sure you could do so was to rapidly become part of the government and focus all your attention on keeping yourself part of the government. Government is, as the great Arab historian Ibn Khaldun liked to say, an organization that prevents all injustice except for that it commits itself. A limited government is a government that binds itself not to commit (much) injustice. Under such a government people can turn their attention to other things. For example, Steve Jobs in Cupertino can turn his attention away from lobbying the government and doing favors to politicians so that they don't steal his stuff, and instead turn his attention to terrorizing the engineers of Apple Computer and otherwise motivating them to produce the best possible successor device next April to this iPad I hold before you.

Some of the answer might be "the Columbian exchange." Starting in 1500 all of a sudden humans start moving all kinds of useful plants across the world--transfer the rubber plant from Brazil to Malaysia, transplant the coffee plant from Ethiopia to Java and from Java to Brazil, transplant the hot Mexican pepper to Sichuan, transplant the Peruvian potato pretty much everywhere. That may have given humans enough of an edge above subsistence to allow them to turn more attention to invention and innovation rather than just trying to keep their heads above water.

It is interesting. We look across the dividing lines of 1500 or 1800 in practically every field of human excellence, and our predecessors speak to us. We still listen to the music of Pachelbel. We still study the orations or some of us study the orations of Cicero. We still examine the campaigns and battles of Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great. We still admire the statues of Michelangelo. Poets, generals, politicians, musicians, sculptors, playwrights, artists--we don’t seem to have much more on the ball than they did, even though there are a lot more of us today and you would expect the law of large numbers to produce more excellence today than in the past.

But the economy is different. Wherever we turn in the economy, we find that the organizations we have have literally nothing to learn from anybody in the past.

So what happened to produce this divide is the big historical question. Because this is a principles of economics class and not an economic history class we are not going to answer them. I recommend that you take a global economic history or a sociology of modernity class. But I don't have time here to cover these issues. Thus next time we are going to talk about not why the industrial revolution occurred, but rather how economies have grown since the industrial revolution.

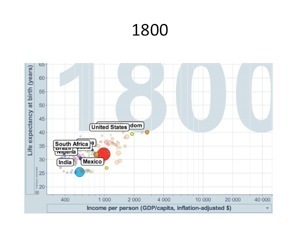

Gapminder.com: Let me close by cutting and pasting from the gapminder.com website which has a bunch of very nicely represented data series on levels of prosperity and standards of living in different countries since 1800 along the horizontal axis and life expectancy at birth along the vertical axis. It shows us how the world was in the 1800, when the great mass of human standard of living is something between $200 and $1000 per capita per year (with China being the big red ball in the middle, and with the United States and the United Kingdom the industrializing societies out there on the prosperous edge).

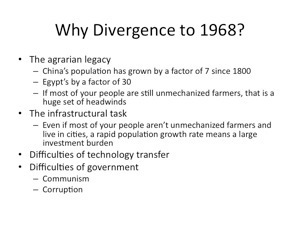

Fast forward to 1968. A whole bunch of countries, mostly in Africa, look very much like they looked back in 1800 with respect to income--but everybody looks much better with respect to public health and life expectancy.

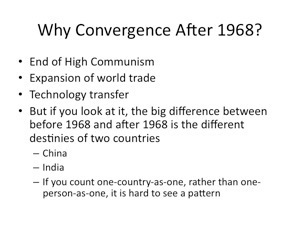

Since 1968 the world has continued to grow and has become a much, much more equal place. The reduction in inequality stems from the fact the big red ball (China) and the big blue ball (India) have joined the upward merge of prosperity bigtime. It is not so much that the universe of countries have been doing different since 1968. It is that two countries have been doing different since 1968: together they are a third of the human race.

The Coronation of Charlemagne

Annales Laurehamenses:

THE CORONATION OF CHARLEMAGNE: Since the title of emperor had become extinct among the Greeks and a woman (Empress Irene) claimed the imperial authority, it seemed to Pope Leo and to all the holy fathers who were present at the council and to the rest of the Christian people that Charles, king of the Franks, ought to be named emperor, for he held Rome itself where the Caesars were always accustomed to reside and also other cities in Italy, Gaul and Germany. Since almighty God had put all these places in his power it seemed fitting to them that, with the help of God, and in accordance with the request of all the Christian people, he should hold this title. King Charles did not wish to refuse their petition, and, humbly submitting himself to God and to the petition of all the Christian priests and people, he accepted the title of emperor on the day of the Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ and was consecrated by Pope Leo.

Vita Leonis III (795-816)

On the day of the Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ all [who had been present at the council] came together again in the same basilica of blessed Peter the apostle. And then the venerable and holy pontiff, with his own hands, crowned [Charles] with a most precious crown. Then all the faithful Romans, seeing how he loved the holy Roman church and its vicar and how he defended them, cried out with one voice by the will of God and of St. Peter, the key-bearer of the kingdom of heaven:

To Charles, most pious Augustus, crowned by God, great and peace-loving emperor, life and victory.

This was said three times before the sacred tomb of blessed Peter the apostle, with the invocation of many saints, and he was instituted by all as emperor of the Romans. Thereupon, on that same day of the nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ, the most holy bishop and pontiff anointed his most excellent son Charles as king with holy oil.

Joe Klein Falls Out of Love with John McCain

Joe Klein:

Two Dreams, One Dead - Swampland - TIME.com: The Senate today passed the repeal of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," which is a good thing. It did not pass the "Dream Act," which is a cold, cold abomination. There is a relationship between the two. Repealing "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" will allow homosexuals--who have fought honorably in every one of America's wars--to serve openly. Blocking the "Dream Act" means that young immigrants, who were brought here illegally by their parents, will not be able to gain citizenship by completing college or by serving in the military.... [L]et us focus for a moment on the "Dream Act," a vote of staggering cynicism and ugliness on the part of most Republicans and five morally-deficient Democrats. Two of the original sponsors, John McCain and Orrin Hatch, voted against the bill... and one wonders why, especially in McCain's case, given the fact that he recently won reelection and doesn't have to pretend to be a troglodyte anymore. McCain has professed himself all misty and honored in the past when he attended ceremonies in which green-card holders and other non-citizens achieved citizenship.... [T]his flagrantly cynical and cowardly politician would deny... status to young people who--through no fault of their own--were brought to this country as children, grew up as Americans and love the country enough to serve it. If the Dream Act were passed, we would have gained an estimated 65,000 valuable, patriotic and productive citizens--college graduates, military service-members--each year. We could use them....

McCain distinguished himself doubly this weekend, opposing the Dream Act and leading the opposition to "Don't Ask," despite the very public positions of his wife and daughter....

I used to know a different John McCain, the guy who proposed comprehensive immigration reform with Ted Kennedy, the guy--a conservative, to be sure, but an honorable one--who refused to indulge in the hateful strictures of his party's extremists. His public fall has been spectacular.... He's a bitter man now, who can barely tolerate the fact that he lost to Barack Obama. But he lost for an obvious reason: his campaign proved him to be puerile and feckless, a politician who panicked when the heat was on during the financial collapse, a trigger-happy gambler who chose an incompetent for his vice president. He has made quite a show ever since of demonstrating his petulance and lack of grace.

What a guy.

December 21, 2010

Money and Marbles

Jim Hamilton:

Econbrowser: Velocity of money: I wanted to follow up on Menzie's recent observations about what's been happening to the supply and demand for money. These discussions are sometimes conducted in terms of the following equation:

MV = PY.

Here M is a measure of the money supply, V its velocity, and nominal GDP is written as the product of the overall price level (P) with real GDP (Y). We have direct measurements on nominal GDP. And once we agree on a definition of the money supply (no trivial matter), we have a number for M. But where do we come up with data on this concept of the velocity of money, V?... [W]e don't.... [W]e measure the velocity of money from

V = PY/M....

[D]ifferent people come up with different answers for how we should measure the money supply. One measure is M1... currency held by the public and checkable deposits... the monetary base... currency held by both banks and the public plus deposits banks hold in their accounts with the Federal Reserve.... You get the idea-- use your favorite M to get your favorite V.

Arnold Kling, for example, proposed that we might use for M the quantity of marbles. Which perhaps sounds a little silly.... [Y]ou could still go ahead and use the equation above to define the velocity of marbles. But what you'd find is that when marbles go up, the marble velocity goes down, and it makes no difference for output or inflation.

OK, so let's look at the velocity of M1. It turns out to look a lot like you'd expect the velocity of marbles to behave-- when M1 goes up, the velocity of M1 goes down by an almost exactly offsetting amount.... So maybe we'd be better off using the monetary base as our value for "M"? I don't think so....

Obviously the interest in an equation like MV = PY comes not from using it as a definition of V for some arbitrary choice of M. Instead there must be some kind of behavioral idea, such as that there is some desired value of M1, or monetary base, or marbles, that people want to hold. Suppose it was the case that to a first approximation, this desired quantity was essentially proportional to nominal GDP. If that were true, we would see the graphs of V above behaving roughly as constants instead of simply tracking the inverse of whatever happens to M.

Now, I think it is true that, in normal times, nominal GDP is one of the most important determinants of the demand for M1 or the monetary base.... But conditions at the moment are far from normal.... The demand for reserves has increased by a trillion dollars since 2008. The demand for currency held by the public has not. The supply of reserves could therefore increase a trillion dollars without causing inflation. The quantity of currency held by the public could not. Now, the time will come when banks do see something better to do with these reserves, at which point the Fed will need to take appropriate measures in response, namely a combination of raising the interest rate paid on reserves and selling off some of the assets the Fed has been accumulating....

But someone who insists that inflation (P) must go up just because the monetary base (M) has risen may have lost their marbles.

The Year Kenny Loggins Ruined Christmas

Hyperbole and a Half:

The Year Kenny Loggins Ruined Christmas: The year I learned that Christmas did not, in fact, originate as a celebration of my amazing ability to temporarily transform into a "good" child for a few weeks was the year my grandparents took me to see their church's nativity play.... From my grandparents' flowery explanation and frequent use of the word "miracle," I went in expecting to be blown away by the production. Unfortunately... the story just seemed to center around everyone being really impressed with Jesus and there wasn't much suspense and not a single battle scene. I could see that the story had potential, but I was deeply disappointed by the whole experience.

By the time my grandparents dropped me off at home, I had convinced myself that I needed to take matters into my own hands and reinvent the birth of Christ so that it conformed to my expectations.... I walked through my front door with purpose and gathered my family members in the living room to tell them about my vision. I was going to rewrite the birth of Jesus Christ and I was going to make it POP. My mom, always wanting to nurture my creative side, agreed on behalf of everyone that we should go forward with the production. I would be playing the part of Mary and my dad would be Joseph. My aunt and my grandma would play the wise men. My mom would be filming...

[...]

For a moment, it seemed as though my outburst had succeeded in bringing my family back into a more serious mindset. But after a few moments of tense silence, my aunt quietly squeaked:

Kenny Loggins wouldn't beat the baby Jesus...

It was over. Any hope I had ever had of getting my family members to act out their parts with integrity was shattered. They laughed and laughed until I thought they were going to asphyxiate on their own wretched spittle.

My mom eventually realized that it was her maternal duty to step in and discipline me when I did things like strike the baby Jesus repeatedly with a blunt object, so she tried to pull herself together and send me to my room:

GO TO YOUR ROOM!

You aren't supposed to hit things with sticks.

Especially not Jesus.

Or...

KEENNNYYY LOGGINNNSSS...

Things You Can Learn on the Internet: Earl Grey Tea

Wikipedia:

In one case study, a patient who consumed 4 litres of Earl Grey tea per day reported muscle cramps, which were attributed to the function of the bergapten in bergamot oil as a potassium channel blocker. The symptoms subsided upon reducing his consumption of Earl Grey tea to 1 litre per day...

Will Wilkinson Says That the Executive of the Modern State Is But a Committee for Managing the Affairs of the Ruling Class...

Didn't somebody else say that, sometime?

Will:

: I should clarify that I did not mean to be pointing out a huge hole in the logic of liberal redistribution. Rather, I was pointing out a problem for the classical progressive idea of the regulatory state as a check on concentrated economic power. In any case, I must say I'm dazzled by the audacity of Mr Chait's claim that the "private capture of public functions" is rare. My reading of the economic and political history of the United States is that regulation is very, very, very often turned into (or originally fashioned) as a weapon of business power.... Mr Chait's regulatory-capture denialism is especially notable when the matter at hand is the Washington-Wall Street nexus, as the case for a significant degree of corporate control over financial regulation is extremely compelling. Indeed, that this revolving door is so well-trafficked constitutes perhaps the most impressive piece of evidence that financial regulators are too bound up socially, professionally, and ideologically with their regulatees to offer impartial oversight in the public interest.... [F]inancial markets are not the only ones largely regulated in the interests of dominant firms.... The federal government's role in radio and television from the 1920s through the 1960s, for instance, was nothing short of a disgrace...

Daniel Klein and Carlotta Stern Makes Their Bid for This Year's Stupidest Economist Alive Crown

It is really too bad the contest has already been won.

Somebody who wishes me ill sends me to proof-texting from Daniel Klein and Carlotta Stern:

Daniel Klein and Charlotta Stern: Is There a Free-Market Economist in the House? The Policy Views of American Economic Association Members

Abstract: People often suppose or imply that free-market economists constitute a significant portion of all economists. We surveyed American Economic Association members and asked their views on 18 specific forms of government activism. We find that about 8 percent of AEA members can be considered supporters of free-market principles, and that less than 3 percent may be called strong supporters.... Even the average Republican AEA member is “middle-of-the-road,” not free-market....

Political economists are in general quite suspicious of governmental intervention. They see in it inconveniences of all kinds--a diminution of individual liberty, energy, prudence, and experience, which constitute the most precious resources of any society. Hence, it often happens that they oppose this intervention... -- Frédéric Bastiat ([1848])

In 1848, Bastiat’s statements were probably true. Nowadays they are not. Here we present evidence from a survey of American Economic Association (AEA) members showing that a large majority of economists are either generally favorable to or mixed on government intervention, and hence cannot be regarded as supporters of free-market principles. Based on our finding, we suggest that about 8 percent of AEA members can be considered supporters of free-market principles, and that less than 3 percent may be called strong supporters...

Would Daniel Klein and Carlotta classify Frederic Bastiat as a "free market economist"? The answer is "no."

Let's turn the microphone over to Frederic Bastiat:

(1) There is an article in the Constitution which states: "Society assists and encourages the development of labor.... through the establishment by the state, the departments, and the municipalities, of appropriate public works to employ idle hands..." As a temporary measure in a time of crisis, during a severe winter, this intervention on the part of the taxpayer could have good effects... as insurance. It adds nothing to the number of jobs nor to total wages, but it takes labor and wages from ordinary times and doles them out, at a loss it is true, in difficult times...

(2) For a nation, security is the greatest of blessings. If, to acquire it, a hundred thousand men must be mobilized, and a hundred million francs spent, I have nothing to say. It is an enjoyment bought at the price of a sacrifice...

(3) It is quite true that often, nearly always if you will, the government official renders an equivalent service to James Goodfellow. In this case there is... only an exchange... my argument is not in any way concerned with useful functions. I say this: If you wish to create a government office, prove its usefulness.... When James Goodfellow gives a hundred sous to a government official for a really useful service, this is exactly the same as when he gives a hundred sous to a shoemaker for a pair of shoes. It's a case of give-and-take, and the score is even...

(4) [L]ast year I was on the Finance Committee. Each time that one of our colleagues spoke of fixing at a moderate figure the salaries of the President of the Republic, of cabinet ministers, and of ambassadors, he would be told: "For the good of the service, we must surround certain offices with an aura of prestige and dignity. That is the way to attract to them men of merit.... A certain amount of ostentation in the ministerial and diplomatic salons is part of the machinery of constitutional governments, etc., etc..." Whether or not such arguments can be controverted, they certainly deserve serious scrutiny. They are based on the public interest, rightly or wrongly estimated; and, personally, I can make more of a case for them than many of our Catos, moved by a narrow spirit of niggardliness or jealousy...

(5) Should the state subsidize the arts?... [A]rts broaden, elevate, and poetize the soul of a nation; that they draw it away from material preoccupations, giving it a feeling for the beautiful, and thus react favorably on its manners, its customs, its morals, and even on its industry. One can ask where music would be in France without the Théâtre-Italien and the Conservatory; dramatic art without the Théâtre-Français... ask whether, without the centralization and consequently the subsidizing of the fine arts, there would have developed that exquisite taste which is the noble endowment of French labor and sends its products out over the whole world.... To these reasons and many others, whose power I do not contest, one can oppose many no less cogent. There is... a question of distributive justice. Do the rights of the legislator go so far as to allow him to dip into the wages of the artisan in order to supplement the profits of the artist?... I confess that I am one of those who think that the choice... should come from below, not from above, from the citizens, not from the legislator.... Returning to the fine arts, one can, I repeat, allege weighty reasons for and against the system of subsidization... in... this essay, I have no need either to set forth these reasons or to decide between them.... When it is a question of taxes [and subsidies], gentlemen, prove their usefulness by reasons with some foundation, but not with that lamentable assertion: "Public spending keeps the working class alive"...

(6) When a public expenditure is proposed, it must be examined on its own merits... a presumption of economic benefit is never appropriate for expenditures made by way of taxation. Why?... In the first place, justice always suffers from it somewhat. Since James Goodfellow has sweated to earn his hundred-sou piece... he is irritated... that the tax intervenes to take this satisfaction away from him and give it to someone else.... [I]t is up to those who levy the tax to give some good reasons for it.... If the state says to him: "I shall take a hundred sous from you to pay the policemen who relieve you of the necessity for guarding your own security, to pave the street you traverse every day, to pay the magistrate who sees to it that your property and your liberty are respected, to feed the soldier who defends our frontiers," James Goodfellow will pay without saying a word...

(7) Another species of spoilation is commercial fraud, a term which seems to me too limited... [when restricted to] the tradesman who changes his weights and measures... the physician who receives a fee for evil counsel, the lawyer who promotes litigation, etc.

So Frederic Bastiat is in favor of:

Stimulative expansionary fiscal policy to fight depressions,

large public expenditures for national security,

government provision of services that government can provide as cheaply and effectively as the private sector,

high salaries for public officials to attract workers of talent and energy and also to boost the prestige and dignity of the government,

subsidies for the arts to the extent that purlic subsidies properly elevate taste and aesthetic values,

public provision of police, justice, defense, transportation, and other infrastructure,

public regulations of professional practice a la the FDA in order to avoid "spoilation" by doctors and pharmaceutical companies that receive "a fee for evil counsel."

Let us be very clear: The key for Frederic Bastiat is whether Jacques Bonhomme receives good value for the government expenditures financed by his taxes. Bastiat does not care whether or not Jacques Bonhomme is "coerced" when he is taxed to pay for public schools, public roads, public theatres, government-run courts, government-paid police officers, government armies. He cares about whether the goods and services that the government provides are valuable ones. The key is whether Jacques Bonhomme receives good value for his private purchases--if not, if the physician or pharmaceutical company provides "evil counsel," then the government has the same duty to intervene via regulation as it does when confronted with fraud in weights and measures.

Klein and Stern say:

Many economists [falsely] maintain that they are essentially free-market supporters but recognize that externalities, asymmetric information, diminishing marginal utility of wealth, etc. call for exceptions.... A “natural rights” libertarian who has no economic understanding is nonetheless a supporter of free-market principles.... At the heart of such principles are private property rights and the freedom of contract.... When a survey respondent does not oppose such coercive government action, it is... a clear case of not supporting free-market principles.... [G]overnment ownership and production of schooling... government programs that draw on taxation and distort or crowd out private enterprise... to not oppose such government programs is to not support free-market principles.... The distinction between voluntary and coercive action is... the basis upon which we call certain cases “the free market” and certain policies “government intervention.” A clear understanding of the distinction is crucial to economics as a scientific enterprise...

We have gone beyond ideology into absurdity.

A definition of "free-market supporter" that excludes Frederic Bastiat from the set is not useful.

J. Bradford DeLong's Blog

- J. Bradford DeLong's profile

- 90 followers