J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 1103

December 21, 2014

Liveblogging World War II: December 22, 1944: Malmedy

World War II Today:

21 December 1944: Malmedy--lone infantryman beats off Panzers:

It was in Malmedy that Sergeant Francis Sherman ‘Frank’ Currey in the 3rd platoon of Company K, 120th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division found himself in charge in the early hours of the 21st December.

The attack towards K Company’s roadblock began as an infantry attack. There was no artillery preparation, in fact, no artillery support at all. When the advancing enemy infantry got within three or four hundred yards of the roadblock’s outpost, they were discovered and fired upon.

A spirited firefight immediately developed. Under the cover of machine gun and direct fire, the attackers advanced and took possession of a house in the vicinity of the crewless TD gun, about 200 yards from the positions of the defending platoon.

The enemy made this house into a strong point and built up a line east thereof. Practically all of the hostile infantrymen carried automatic weapons.

After about six hours, during which the men of Company K fought off all efforts of the German infantry to overrun their position, the supporting hostile tanks moved forward up the road in an effort to break the resistance, which the infantry had been unable to do.

From the original 30th Division historical narrative:

We were guarding a bridge, a very vital bridge,

About four o’clock the next morning, here come the German tanks almost bumper to bumper, an armored column. One of them pulled right up to our position, and I had a Browning automatic rifle at the time, and the officer leading the column was up in the turret, and I fired at him, buttoned him up, and the others scattered.

…

We withdrew to this factory. It had a lot of windows in it, and we were firing from a window. ‘Move, fire, move, fire’ And made them think that we were a lot more than we actually were.

[Under cover of darkness, Sergeant Currey and his men escaped in an abandoned jeep.]

Now, visualize, five young men, the oldest 21-years-old, in the middle of Belgium, when it was dark. We couldn’t use lights on the jeep. We were surrounded by Germans. That’s youth!

See Hurleyville website for more. Currey was awarded the Medal of Honor, the citation for which describes the action in much more detail:

He was an automatic rifleman with the 3d Platoon defending a strong point near Malmedy, Belgium, on 21 December 1944, when the enemy launched a powerful attack.

Overrunning tank destroyers and antitank guns located near the strong point, German tanks advanced to the 3d Platoon’s position, and, after prolonged fighting, forced the withdrawal of this group to a nearby factory.

Sgt. Currey found a bazooka in the building and crossed the street to secure rockets meanwhile enduring intense fire from enemy tanks and hostile infantrymen who had taken up a position at a house a short distance away. In the face of small-arms, machinegun, and artillery fire, he, with a companion, knocked out a tank with 1 shot.

Moving to another position, he observed 3 Germans in the doorway of an enemy-held house. He killed or wounded all 3 with his automatic rifle. He emerged from cover and advanced alone to within 50 yards of the house, intent on wrecking it with rockets.

Covered by friendly fire, he stood erect, and fired a shot which knocked down half of 1 wall. While in this forward position, he observed 5 Americans who had been pinned down for hours by fire from the house and 3 tanks. Realizing that they could not escape until the enemy tank and infantry guns had been silenced, Sgt. Currey crossed the street to a vehicle, where he procured an armful of antitank grenades. These he launched while under heavy enemy fire, driving the tankmen from the vehicles into the house.

He then climbed onto a half-track in full view of the Germans and fired a machinegun at the house. Once again changing his position, he manned another machinegun whose crew had been killed; under his covering fire the 5 soldiers were able to retire to safety.

Deprived of tanks and with heavy infantry casualties, the enemy was forced to withdraw. Through his extensive knowledge of weapons and by his heroic and repeated braving of murderous enemy fire, Sgt. Currey was greatly responsible for inflicting heavy losses in men and material on the enemy, for rescuing 5 comrades, 2 of whom were wounded, and for stemming an attack which threatened to flank his battalion’s position.

Weekend Reading: Rick Perlstein in Democracy Journal on Why Jacob Weisberg's Reviewing License Should Be Withdrawn

Over at Democracy Journal:

Rick Perlstein:

The Reason for Reagan, Democracy Journal: Understanding Ronald Reagan requires looking beyond clichés to the cultural climate of the time. A response to Jacob Weisberg:

In 1980, the year Ronald Reagan won his first landslide presidential victory, pollsters at National Opinion Research Corporation asked Americans whether they thought, as Reagan did, that ‘too much’ was being spent on welfare, health, education, environmental, and urban programs. Only 21 percent did—the same percentage as had answered that way in 1976. The number that favored ‘keeping taxes and services about where they are’ was a healthy plurality, 45 percent—the exact same result as in 1975. READ MOAR

The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations did a similar poll in 1982, and found that since 1978, the year of the much-vaunted national tax revolt spearheaded by Proposition 13 in California, the percentage of Americans who wished to see welfare programs expanded rather than cut back had increased by 26 percentage points. In 1984, the year Reagan won 49 states and 59 percent of the popular vote, only 35 percent of Americans said they favored substantial cuts in social programs in order to reduce the deficit.

Given these plain facts, historiography on the rise of conservatism and the triumph of Ronald Reagan must obviously go beyond the deadening cliché that since Ronald Reagan said government was the problem, and Americans elected Ronald Reagan twice, the electorate simply agreed with him that government was the problem. But in his recent review of my book The Invisible Bridge [‘A Bridge Too Far,’ Issue #34], Jacob Weisberg just repeats that cliché—and others. ‘Rick Perlstein’s account of Reagan’s rise acknowledges his popularity,’ the article states, ‘but doesn’t take the reasons behind it seriously enough.’ Weisberg is confident those reasons are obvious. Is he right?

Begin with his opening judgment. He says Reagan’s stubborn insistence that Watergate didn’t matter was ‘anodyne’ and ‘the safe political course.’ Then why was he the only prominent political figure taking that position? Why did political handicappers like Rowland Evans and Robert Novak call it professional suicide, quoting aides agonizing that Reagan could go no further in his career until he made (in Evans and Novak’s words) that ‘politically necessary rupture’? (He never did.) Weisberg’s claim simply contradicts the record. For that matter, I did not say that there was a ‘deeper motive in Reagan’s evasion of the crisis.’ No: It was just Reagan being Reagan. And, as I demonstrate throughout The Invisible Bridge, Reagan being Reagan—projecting blitheness in the face of what others called chaos, in addition to being a shrewd politician, a gifted rhetorician, and an inventive beneficiary of the growing organizational forces of professional conservatism—is how his candidacy for the 1976 Republican presidential nomination evolved from an improbability to a near miss, and from that to his 1980 victory. It was not some unproblematic rallying of the masses to his skepticism of government.

Weisberg dislikes my method for arriving at this conclusion, which for his taste involves far too much use of everyday contemporary media sources. ‘[F]or long stretches, reading this book feels like leafing through a lot of old newspapers,’ he writes. Another way of understanding this, though—and, in addition to old newspapers, I’d add old newscasts, old magazines, old movies, old TV shows, old comic strips, old barroom and barbershop conversations, old shopping trips, old Mad magazines and Wacky Packages, old TV commercials and magazine ads and high school textbooks, etc.—is that I do history. I try to do it the way my methodological guide, the British philosopher R.G. Collingwood, described the ideal in his 1946 masterpiece, The Idea of History: by providing the reader occasion to empathetically ‘re-enact’ past thought.

‘[R]ather than present a case,’ Weisberg writes of this method, I indulge ‘the newsmagazine writer’s habit of substituting glib narrative for coherent argument.’ Perhaps it’s a matter of taste. But for me, conveying how the headlong rush of all that was solid melting into air felt, in the nation that defeated Hitler and created the world’s first mass middle class and which had seen itself as the moral light unto the nations, is anterior to understanding how politics changed during the period under study—why supporting Reagan became a temptation even for those indifferent to top marginal tax rates or runaway government bureaucracies. You can’t separate the dancer from the dance.

Other questions point to the reviewer’s inattentiveness. ‘Perlstein pays a lot of attention to cinema, but little to TV.’ He must have missed Chapter 1, which builds the narrative foundation partly on how the nightly newscasts covered the Vietnam prisoners of war. Or the ground-up account of the experience of watching the Senate Watergate hearings in 1973, and the House Judiciary Committee impeachment hearings in 1974. Or the crucial role my extended discussion of ‘M*A*S*H’ plays in Chapter 15, or my discussion of ‘The Waltons,’ Dean Martin’s celebrity roasts, TV coverage of the 1976 Winter Olympics, and more.

And then:

…still less to pop music, and none at all to literature. How can one write a cultural history of the 1970s without delving into ‘All in the Family,’ Born to Run, or John Updike?

Well, the cultural impact of ‘All in the Family’ was nugatory by the time my story begins. As to Born to Run, despite Bruce Springsteen’s coup of appearing simultaneously on the covers of Time and Newsweek in 1975, its stay near (never on) the top of the Billboard 200 album chart lasted less than a month. ‘It is a folly of too many,’ Jonathan Swift once remarked, ‘to mistake the echo of a London coffee-house for the voice of the kingdom.’ In fact, the albums people were actually listening to much, much more were Chicago IV, Elton John’s Greatest Hits, and Captain & Tennille’s Love Will Keep Us Together; and—so sue me—I’m just not sure what inner cultural logic those sources reveal. And I do talk about Updike, though I talk more about the far-better-selling Alive (a surprise hit among evangelicals). The choices I make are not accidents.

But what of my ‘failure to engage seriously with ideas’? Sometimes ideas have a powerful motor force in history. Sometimes they do not. So it’s the historian’s job to discern which, what, when, and how actual ideas actually affect the course of history, or not. ‘Ideas’—in the sense of serious intellectual work that diffuses outward to influence a wider public—were very important in the later 1970s, when the writings of formerly liberal intellectuals known as ‘neoconservatives’ did so much to make conservatism respectable to journalistic and political elites. But ideas in that sense were not, in my considered judgment, nearly as influential in the rise of conservatism earlier in the 1960s and ’70s—just a little bit, which is why I write about them only a little bit.

Historians are frequently biased toward overemphasizing ideas, because as intellectuals they find ideas interesting. There is also a bias—elsewhere I’ve called it a soft bigotry of low expectations—toward plumping up conservative intellectual work because it makes a liberally inclined historian sound fair. I first learned to distrust conservatives’ own protestations that theirs is a ‘movement of ideas’ when I read a speech transcript from a right-wing congressman in 1962 backing his defense of laissez-faire economics by dropping the name of Edmund Burke, who had less than nothing to do with laissez-faire economics. ‘Ideas’ in politics are often intuition in fancy dress.

You can read Hayek, Mises, or Friedman in order to understand how and why conservatives hold government intervention in the marketplace with contempt; or you can read a speech by a Chamber of Commerce executive in the 1920s, or an exchange of letters between factory owners in the 1950s, all of them managing to enunciate the very same thing without the benefit of scholarly clergy. And indeed, the vaunted ideas themselves are often not particularly deep, which is why General Electric was able to distribute Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom to its employees in comic book form.

Weisberg is also inattentive to those moments when I do examine ideas. I write in detail, for instance, about the influence of economist Henry Hazlitt on Ronald Reagan. (But not Milton Friedman, because the evidence of his radio broadcast suggests he began influencing Reagan in the fall of 1976, after my narrative ends. I’ll be writing a lot about Friedman in my next volume, covering the years 1977 to 1981.) He writes that ‘Perlstein might give more weight to the visible bridge of Reagan’s stated views,’ singling out those on welfare; but did he not notice my extensive (and laudatory) discussion of Reagan’s welfare reforms as governor in Chapter 18? He mentions my alleged lacuna concerning taxes. But I write a lot about Reagan and taxes, and where his ideas about them came from: It’s inside one of my three chapters, ranging over some 102 pages, specifically about what made Reagan tick.

Perhaps Weisberg skipped those, because he writes, ‘Perlstein doesn’t wonder about what made Reagan tick.’

Chronology matters, too, when it comes to ideas. Facts matter. Sources matter. Why didn’t I write about taxes as a formative conservative issue in the first half of the 1970s? Because, for the most part, they weren’t one. Weisberg claims:

With a top marginal rate of 70 percent kicking in at just over $100,000 for individuals (or around $275,000 in adjusted terms), income taxes were both too high and, with as many as 25 brackets, gratuitously complex.

(Actually, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that $100,000 kick-in point—$200,000 for married couples—adjusts in the years my study covers not to his claimed $275,000 but from a low of $418,000 to a high of $535,000.) Taxes just weren’t really a partisan issue during the period I’m writing about. As I point out on page 627, cleaning up the complexity of the tax code, which he liked to call a ‘disgrace,’ was a central part of Jimmy Carter’s platform in 1976.

Weisberg thinks I ‘pathologize conservative views.’ There are many pages in my book I could cite in refutation, but for the sake of brevity I’ll single out Chapter 15. That is where, amid my sympathetic discussion of the backlashes against liberal textbooks in Kanawha County, West Virginia, and against federal Judge Arthur Garrity’s desegregation decision in Boston, I write about how dispossessing it must have felt to be an ordinary American of conservative temperament in a liberalizing culture all but taken for granted by everyone who mattered in the media—institutionalized, for example, in hit TV shows like ‘M*A*S*H’ and in a popular high school history textbook that spoke of American capitalists as having ‘crushed the dreams of poor people.’

I describe a weary despair aimed at ‘liberal media gatekeepers who had made ordinary longings for simple order, tradition, and decorum suddenly seem so embarrassingly unfashionable.’ I note that old-fashioned patriotism ‘felt somehow forbidden,’ and I describe feelings of victimization ‘by a sort of radicalism that, because it graced Middle American classrooms, did not seem radical to most Americans at all.’ Among those who found empathy in such formulations was The Wall Street Journal’s Max Boot, who noted that I reserve ‘some of [my] most cutting barbs…for clueless establishment liberals who all too readily dismissed the significance of conservative champions.’

In some places Weisberg accuses me of writing things I did not actually write. I never accuse Reagan of ‘telling lies.’ Read carefully: I point out where he contradicted himself. Or said strange things that that were demonstrably untrue, or embellished, or repeated things he claimed were facts long after they had been debunked, or changed opinions while claiming he hadn’t changed them at all. That was, indeed, part of what made Reagan tick. For instance, concerning ‘Henry Kissinger’s amoral realpolitik’: Reagan defended it consistently and adamantly when Nixon was President, as I show, and excoriated it consistently and adamantly when Ford was President. Scholars of Reagan need to account for this, to venture arguments about why this was the case. Or should we ignore it? Does Weisberg think the legacy of Ronald Reagan can’t handle the truth?

‘Ronald Reagan,’ Weisberg writes:

was refining Goldwater’s pitch, shedding the warmongering, the pessimism, and the anti-New Deal extremism.’

No. He called the New Deal ‘fascism.’

Weisberg continues:

Reagan’s views were not simply Goldwater’s views; they were Goldwater’s views purged of their excesses and abstraction, grounded in the country’s lived experience, and given a hopeful cast.

This is an understandably tempting view, but quite ahistorical. There was much in the words I quote from Reagan’s that was mind-blowingly excessive, unrefined, and not hopeful at all: For instance, that teachers unions were following a script laid down by Hitler and the Nazi Party. Of course, he said other things, too, more hopeful, less excessive, and better grounded. It’s complicated. The writing of history must honor that complexity—and not just resort to tempting cliché.

Noted for Your Nighttime Procrastination for December 21, 2014

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Heather Boushey: You Can’t Help Today’s Middle Class with 1930s-Era Policies

Nick Bunker: Weekend Reading

Nauro Campos: The Riddle of Argentina

William H. Davidow and Michael S. Malone: What Happens to Society When Robots Replace Workers?

Plus:

Things to Read at Night on December 21, 2014

On Twitter:

Tech Words That Should Not Be (with images, tweets) · delong · Storify

Marxism vs. Liberalism vs. Conservatism (with image, tweets) · delong · Storify

Must- and Shall-Reads:

Scott Lemieux:

"The only two presidents who can even arguably been said to have presided over a more substantial body of progressive policy-making in the last century are FDR and LBJ, and both did so in significantly more favorable contexts..."

Simon Wren-Lewis:

Money Impotence in context

Miles Kimball:

Righting Rogoff on Japan's Monetary Policy

The Enlightened Economist:

Inequality, Economics and Politics: Thomas Piketty at the Bank of England

"Christopher Eppig and his colleagues... note that the brains of newly born children require 87% of those children's metabolic energy.... five-year-olds... 44% and even in adults... a quarter.... Any competition for this energy is likely to damage the brain's development, and parasites and pathogens compete for it in several ways..."

William Davidow and Michael S. Malone: What Happens to Society When Robots Replace Workers?

Nauro Campos: The Riddle of Argentina

Heather Boushey: You can’t help today’s middle class with 1930s-era policies

Nick Bunker: Weekend reading

Karl Whelan: Thoughts on “Teaching Economics After the Crash”

Miles Kimball:

John Stuart Mill on Being Offended at Other...

And Over Here:

Liveblogging World War II: December 22, 1944: Malmedy

(Early) Monday DeLong Smackdown Watch: Paul Krugman: The Simple Analytics of Monetary Impotence

Liveblogging World War II: December 21, 1944: Siege of Bastogne

Guy Vidra's Open Letter to "New Republic" Readers

Weekend Reading: Karl Whelan: Thoughts on “Teaching Economics After the Crash”

Liveblogging World War II: December 20, 1944: The Radio News

For the Weekend...

William Davidow and Michael S. Malone:

What Happens to Society When Robots Replace Workers?:

"Henry Adams... estimated that power output... between 1840 and 1900 [had] a compounded rate of progress of about 7% per year.... 1848... speed... 60 miles per hour. A century later... 600... a rate of progress of only about 2% per year. By contrast, progress today comes rapidly... semiconductor technology has been progressing at a 40% rate for more than 50 years. These rates of progress are embedded in the creation of intelligent machines, from robots to automobiles to drones, that will soon dominate the global economy.... We will soon be looking at hordes of citizens of zero economic value. Figuring out how to deal with the impacts of this development will be the greatest challenge facing free market economies in this century..."

Nauro Campos:

The Riddle of Argentina:

"Argentina is the only country in the world that was 'developed’ in 1900 and ‘developing’ in 2000.... Financial development and institutional change are [probably] two main factors behind the unusual growth trajectory of Argentina over the last century.... Some argue that the decline started with the Great Depression (e.g. Diaz-Alejandro 1985)... Taylor (1992) argues for 1913.... Yet by 1947 Argentina was still ranked 10th in the world in terms of per capita income and della Paolera and Taylor (2003) estimate that the ratio of Argentina’s to the OECD’s income declined to 84% in 1950, to 65% in 1973, and then to 43% in 1987. It rebounded in the 1990s but with the run-up to the 2001 crisis again reverted.... The PGARCH multivariate analysis reveals a robust positive effect of the development of domestic financial institutions (private and savings bank deposits to GDP) as well as a negative growth effect from the instability of informal institutions (chiefly general strikes and guerilla warfare). As for the indirect effects on economic growth (through growth volatility), the results support negative roles for formal political instability (constitutional changes) and trade openness.... The main lesson... is one that economic historians already knew... institutions do matter but among them, political institutions and financial institutions seem fulcral..."

Heather Boushey:

You can’t help today’s middle class with 1930s-era policies:

"America’s families look very different today than a generation or two ago. Too many families fear they are falling out of the middle class or will never get there due to a combination of stagnating wages, rising and high levels of income and wealth inequality, and an increase in jobs with unpredictable schedules and too few benefits. Yet, our workplaces are matched to a very different time. The foundation for labor standards in the United States are grounded in a set of policies implemented in the 1930s. They include the minimum wage, overtime provisions and unemployment insurance. This basket of social insurance programs presumes a specific kind of work and family structure that was prevalent then, but is not the norm now..."

Nick Bunker:

Weekend reading:

"Cardiff Garcia asks whether household formation... will pick up.... Matt O’Brien argues that the bad news [for the Russian economy] won’t end any time soon.... Paul Krugman points to the large private-sector debts that Russia ran up.... Neil Irwin... countries with large social insurance states have the highest employment rates. Danielle Kurtzleben... the stark gender divide in low-wage work.... Dietz Vollrath... [on] the difficulty of calculating productivity growth in the service sector..."

Karl Whelan:

Thoughts on “Teaching Economics After the Crash”:

"This is a long post on the state of economics and how it is taught to undergraduates. The world is not crying out for another such discussion, so blame Tony Yates, via whom I ended up listening to Aditya Chakrabortty’s documentary.... Like Tony, I viewed the programme as a hopelessly one-sided critique of the economics profession. Still, it was useful in the sense that it packed all the regular criticisms about economics into one short piece. I agree with most of what Tony wrote but I want to take a different approach because I think it’s worth engaging a bit more positively with the criticisms raised..."

Miles Kimball:

John Stuart Mill on Being Offended at Other...:

"In On Liberty, Chapter IV, ‘Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual’ paragraph 12, John Stuart Mill effectively downplays the problem of direct preferences over others’ conduct or opinions by arguing that preferences over others’ self-regarding conduct or others’ opinions tend to be weak compared to the strength of preferences over one’s own conduct or opinions: 'There are many who consider as an injury to themselves any conduct which they have a distaste for, and resent it as an outrage to their feelings; as a religious bigot, when charged with disregarding the religious feelings of others, has been known to retort that they disregard his feelings, by persisting in their abominable worship or creed. But there is no parity between the feeling of a person for his own opinion, and the feeling of another who is offended at his holding it; no more than between the desire of a thief to take a purse, and the desire of the right owner to keep it...'"

Should Be Aware of:

Joyce Miller:

"In fact, The Invisible Backpack [of White Privilege] contains the complete works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, along with the Western Canon... It’s handy to have a rich literary tradition to provide a validation of selfhood verging on the grandiose... with a detachable Gore-Tex underdog mentality that serves to justify the backpack’s pathological egotism, it often makes me consider writing a novel of my own..."

Chad Orzel:

Method and Its Discontents:

"I have a lot of sympathy for the defenders of method... calls to scrap falsifiability are mostly in service of the multiverse variants of string theory. And I find that particular argument kind of silly and pointless.... I’m sort of at a loss as to why ‘There are an infinite number of universes out there and one of them was bound to have the parameters we observe’ is supposed to be better than ‘Well, these just happen to be the values we ended up with, whatcha gonna do?’ I mean, I guess you get to go one step further before throw up your hands and say ‘go figure,’ but it’s not a terribly useful step.... I’m probably most sympathetic with the view expressed by Sabine Hossenfelder in her post at Starts With a Bang.... 'It is beyond me that funding agencies invest money into developing a theory of quantum gravity, but not into its experimental test. Yes, experimental tests of quantum gravity are farfetched. But if you think that you can’t test it, you shouldn’t put money into the theory either.'...I just don’t really believe we’ve exhausted all the options for testing theories, just because one particular approach has hit a bit of a dry spell. There are almost certainly other paths to getting the information we want, if people put a bit more effort into looking for them..."

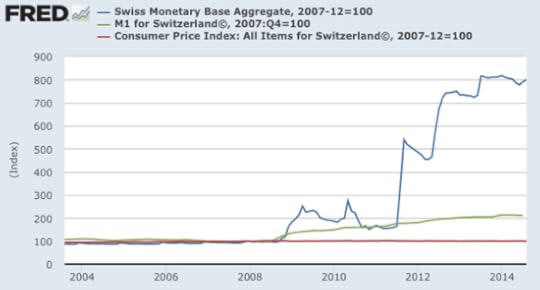

Paul Krugman:

The Dr. Oz Effect:

"There are a lot of [Dr.] Ozzes out there, including in areas you might not consider the entertainment business.... Conference planners tried to recruit me for an event in which I would be presenting the alternative view to the main experts--Arthur Laffer... who among other things warned about soaring inflation and interest rates thanks to the rapid growth in the monetary base... and the Stephen Moore who was caught using fake numbers to promote state-level tax cuts.... These ‘experts’ appeal to the political prejudices of a business audience, but taking their advice would have cost you a lot of money. So why isn’t their popularity dented by the repeated pratfalls? Are they, also, in the entertainment business? To some extent... yes. Simon Wren-Lewis... [says] the financial sector buys into really bad macroeconomics... [because] economists working for financial institutions... earn their money by telling stories that interest and impress their clients. To do that it helps if they have the same worldview as their clients. Thinking about Dr. Oz also... helps explain... [why] the right wants alleged experts who toe the ideological line, why can’t it get guys... recruit[s] and continue[s] to employ people who can’t do basic job calculations, or read their own tables and notice that they’re making ridiculous unemployment projections.... Anyone competent enough to avoid these mistakes would also be unreliable.... I now also suspect that the personality traits you need to be an effective entertainer on inherently not-so-much-fun subjects like health or monetary policy are inherently at odds with the traits you need to be even halfway competent.... A hired-gun economist who actually knows how to download charts from FRED probably wouldn’t have the kind of blithe certainty in right-wing dogma his employers want. So how do those of us who aren’t so glib respond? With ridicule, obviously. It’s not cruelty; it’s strategy."

Simon Wren-Lewis:

Bond Market Fairy Tales:

"When it comes to an issue involving financial markets, then it seems obvious who mediamacro should believe. Those close to the markets surely must know more about how those markets work than some unworldly academic. This post will suggest a more nuanced view.... Are we talking about what may happen over the next few days or weeks, or are we talking about what will happen over the next few years? In terms of very short term prediction, financial market economists beat academic economists.... Those working in the markets are not as concerned about the longer term.... Money is made in predicting short term movements, and knowledge of where things are going over the next few years is a relatively weak guide to what might happen over the next few days.... Economists working for financial institutions spend rather more time talking to their institution’s clients than to market traders. They earn their money by telling stories that interest and impress their clients. To do that it helps if they have the same worldview as their clients. Getting things right over the longer term seems less important.... It is also useful if they leave their clients with the impression that they have some unique insight.... So instead of suggesting... markets are governed by basic principles, it is better to suggest that the market is like some capricious god, and they are one of a few high priests who can detect its mood.... The incentive system for academics is very different..."

Benjamin Schwartz:

The American Conservative’s Christmas Reading:

"I’d read the cuboid book (848 pages) The Making of the English Working Class, by E.P. Thompson... the way that undergraduates too often read—too rapidly, for the purpose of regurgitating arguments in a seminar and to root out facts.... Revisiting it now... the book has given me the most exhilarating experience of my reading life this year.... How between 1780 and 1832 the culture, traditions, and economy of artisans, small producers, tradesmen, and the yeomanry gave way to wage labor, the factory system, and mass industrialization.... Thompson summoned up the causes, arguments, and stratagems of a nearly wholly forgotten political culture... industrial capitalism was uprooting communities, devaluing purposeful work, corroding family life, and concentrating wealth, resources, and production into... ‘but two classes of men, masters and abject dependents.’ Lost were the traditional values of liberty, independence, and individualism—and the open, confident, and generous approach to life those values engender. Won was a steely and resilient class consciousness.... This is a work, Thompson unabashedly makes clear, about history’s losers, and in its embrace of the losers, as well as in other ways, The Making of the English Working Class is a profoundly anti-progressive book.... Thompson’s historical imagination and sympathy allowed him to see the value, and the tragedy, of lost causes: 'I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver, the ‘utopian’ artisan… from the enormous condescension of posterity. Their crafts and traditions may have been dying. Their hostility to the new industrialism may have been backward-looking. Their communitarian ideals may have been fantasies. Their insurrectionary conspiracies may have been foolhardy. But they lived through these times of acute social disturbance, and we did not. Their aspirations were valid in terms of their own experience; and, if they were casualties of history, they remain, condemned in their own lives, as casualties. Our only criterion of judgement should not be whether or not a man’s actions are justified in the light subsequent evolution. After all, we are not at the end of social evolution ourselves. In some of the lost causes of the people of the Industrial Revolution we may discover insights into social evils which we have yet to cure.'"

(Early) Monday DeLong Smackdown Watch: Paul Krugman: The Simple Analytics of Monetary Impotence

Paul Krugman:

The Simple Analytics of Monetary Impotence:

"Monetary policy at the zero lower bound....

...Many... economists... don’t know about an analytical approach that, it seems to me, lets you cut through most of the confusion.... An infinite-horizon model... all the action takes place in period 1.... P* is the period 2 price level, C* the period 2 consumption level... un-asterisked symbols refer to period 1... no investment, just consumption....

What determines period 1 consumption?... If we have rational expectations and frictionless capital markets--which we don’t, but let’s see what would happen if we did--the... ratio of marginal utilit[ies]... equal[s] the relative price of consumption in the two periods, where the relative price is the real discount rate.... Assume logarithmic utility, so that marginal utility is 1/C. Then... C = C*(P*/P)/(1+r).... [This] Euler equation... lets us read off current consumption from future consumption, current and future price levels, and the interest rate....

In a New Keynesian world... prices are... sticky.... At the zero lower bound... r=0.... There’s only one moving part... the expected future price level. Anything... affects current consumption to the extent, and only to the extent, that it moves the expected future price level.... What you do now matters only to the extent that people take it as an indication of what you will do in the future. Don’t talk to me about monetary neutrality, or how it stands to reason that money must matter, or helicopter money, or even money-financed deficits; we’ve taken all of that into account en passant with the Euler equation....

I’m not claiming that this Euler equation is The Truth. If you want to make arguments about policy that rely on some failure of the assumptions, especially imperfect capital markets, fine. But that’s not what I hear... what I hear instead are... unintentional... word games. Instead of telling a specific story about what people are supposed to be doing and why, economists try to reason in terms of concepts like 'monetary neutrality' that aren’t as well-defined as they think, and end up fooling themselves into believing that they’ve demonstrated things they haven’t.

Now, one good exception is Brad DeLong’s argument: that money does too work in a liquidity trap because such traps are always the result of disrupted financial markets.

What I’d say is that they are sometimes caused by financial disruption. But is this one of those times? As the chart shows, we had a lot of disruption in 2008-9. Is that still a major factor in our economic weakness? Do we think that Japan’s problems have been rooted in the banking system all these years? Anyway, that’s how I see it. If you disagree, please try to put your argument in terms of what the people in your model are doing--not in high concepts...

Touché...

I am not going to get very far by claiming that a BAA-Treasury bond spread of 250 rather than 170 basis points indicates enormous credit-rationing of borrowing by companies that are BAA--especially since, almost invariably, their earnings right now are very healthy and their cash flow is such that they are investing in rather than borrowing from financial markets--am I?

The smackdown consists of two parts:

My household liquidity-constraints argument is really not monetary policy but fiscal policy: a transfer now to households with high marginal propensities to consume matched by future taxes in an environment in which household Ricardian equivalence is broken. I (or Miles Kimball) can call it a Federal Lines of Credit program--and claim that it is not expansionary fiscal policy but rather monetary policy, as we implement it by having everyone with a Social Security number automatically incorporated in Delaware as a bank holding company, join the Federal Reserve, and use the Discount Window--but it really is, when you get down to it, fiscal policy.

Credit spreads are back to normal, which means that the amount of moral hazard-driven credit rationing in financial markets is back to normal, and we do not usually think of that as a first-order macroeconomic phenomenon.

My first response is that I want to reserve the term "expansionary fiscal policy" to apply only to those situations in which the policy requires that the government, in order to balance its accounts, impose taxes on future taxpayers who are not the direct recipients of funds from or the direct beneficiaries of the program. Fiscal policy requires the use of the taxing power. Monetary policy buys and sells assets at market prices. I think this distinction makes more sense than Paul's, which classifies FLC programs as fiscal policy. But this is angels-on-pinheads territory.

My second response would have to be something like this: BAA-Treasury credit spreads are back to normal. But equity earnings yield-Treasury yield spreads are not. Nor is household access to mortgage finance back to normal either.

Maybe you don't want to call an 8%/year equity return premium vis-a-vis Treasury bills a "disrupted financial market" that is unable to properly mobilize the risk-bearing capacity of society/screen and classify investment project risks.

But what, then, do you want to call it?

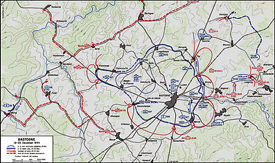

Liveblogging World War II: December 21, 1944: Siege of Bastogne

Wikipedia:

Siege of Bastogne

:

The 101st Airborne formed an all-round perimeter using the 502nd PIR on the northwest shoulder to block the 26th Volksgrenadier, the 506th PIR to block entry from Noville, the 501st PIR defending the eastern approach, and the 327th GIR scattered from Marvie in the southeast to Champs in the west along the southern perimeter, augmented by engineer and artillery units plugging gaps in the line. The division service area to the west of Bastogne had been raided the first night, causing the loss of almost its entire medical company, and numerous service troops were used as infantry to reinforce the thin lines. CCB of the 10th Armored Division, severely weakened by losses to its Team Desobry (Maj. William R. Desobry), Team Cherry (Lt. Col. Henry T. Cherry), and Team O'Hara (Lt. Col. James O'Hara) in delaying the Germans, formed a mobile 'fire brigade' of 40 light and medium tanks (including survivors of CCR 9th Armored Division and eight replacement tanks found unassigned in Bastogne).

Three artillery battalions were commandeered and formed a temporary artillery group. Each had twelve 155 mm (6.1 in) howitzers, providing the division with heavy firepower in all directions restricted only by its limited ammunition supply. Col. Roberts, commanding CCB, also rounded up 600+ stragglers from the rout of VIII Corps and formed Team SNAFU as a further stopgap force.

As a result of the powerful American defense to the north and east, XLVII Panzer Corps commander Gen. von Lüttwitz decided to encircle Bastogne and strike from the south and southwest, beginning the night of 20/21 December. German panzer reconnaissance units had initial success, nearly overrunning the American artillery positions southwest of Bastogne before being stopped by a makeshift force. All seven highways leading to Bastogne were cut by German forces by noon of 21 December, and by nightfall the conglomeration of airborne and armored infantry forces were recognized by both sides as being surrounded.

The American soldiers were outnumbered approximately 5-1 and were lacking in cold-weather gear, ammunition, food, medical supplies, and senior leadership (as many senior officers, including the 101st's commander—Major General Maxwell Taylor—were elsewhere). Due to the worst winter weather in memory, the surrounded U.S. forces could not be resupplied by air nor was tactical air support available due to cloudy weather.

However, the two panzer divisions of the XLVII Panzer Corps—after using their mobility to isolate Bastogne, continued their mission towards the Meuse on 22 December, rather than attacking Bastogne with a single large force. They left just one regiment behind to assist the 26th Volksgrenadier Division in capturing the crossroads. The XLVII Panzer Corps probed different points of the southern and western defensive perimeter in echelon, where Bastogne was defended by just a single airborne regiment and support units doubling as infantry. This played into the American advantage of interior lines of communication; the defenders were able to shift artillery fire and move their limited ad hoc armored forces to meet each successive assault....

The most famous quote of the battle came from the 101st’s acting commander, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe. When confronted with a written request from German General Luttwitz for the surrender of Bastogne, his reply was one word: "NUTS!" (the commander of the 327th GIR interpreted it to the German truce party as "Go to hell!").[13] After the battle, newspapers referred to the division as the "Battered Bastards of Bastogne".

The 101st Airborne Division's casualties from 19 December 1944 to 6 January 1945 were 341 killed, 1,691 wounded, and 516 missing. The 10th Armored Division's CCB incurred approximately 500 casualties.

December 20, 2014

Guy Vidra's Open Letter to "New Republic" Readers

Guy Vidra:

Open Letter to New Republic Readers:

"I started my career in journalism...

...My first job out of college was as a junior editor for a small publication in Dublin, Ireland. When I moved back to the United States, I worked as a copy editor for a company many do not remember today called Bridge News. At the time, Bridge was one of the largest financial news providers in the world but was quickly displaced by a faster moving competitor, Bloomberg. It was the first of many times in my career when I witnessed a traditional media outlet upended by a new competitor on the landscape.

My career has provided me with the privilege of working with some of the world’s best publishers. I have sat beside talented writers and editors and share their dedication to informing society and impacting the world through analysis and insight. I also saw those newsrooms suffer through round after round of layoffs. I saw resources cut. I heard prognostication that the world of publishing was nearing its end. Only one or two of us will remain, many said. In the last few years, however, we’ve seen publishers old and new defy those predictions.... through an array of different strategies--all of which use technology in the service of journalism....

I firmly believe that those who say that this publication was only ever meant to reach a small audience are wrong.... The New Republic has always been a place where contrarian views were embraced and ideas with impact flourished... published an unparalleled back of the book for decades and always sought to provide depth of ideas and high-mindedness to our society and our world.... There is a hunger for depth of ideas. We will provide that depth....

When we spend the time and energy to do a longform piece, we will create formats for our readers to engage with that information outside of print... immerse themselves in that story... imagery and video... tools to let you tailor the types of stories you read depending on the time of day or where you may be... writers and editors... product managers, engineers, designers, data visualization and multimedia editors.... What will not change is our dedication to the ideals that underpin our institution—experimentation, opinion, argument, ideas, and quality.

December 19, 2014

Weekend Reading: Karl Whelan: Thoughts on “Teaching Economics After the Crash”

Karl Whelan:

Thoughts on “Teaching Economics After the Crash”:

"This is a long post on the state of economics...

...and how it is taught to undergraduates. The world is not crying out for another such discussion, so blame Tony Yates, via whom I ended up listening to Aditya Chakrabortty’s documentary ‘Teaching Economics After the Crash’ for BBC Radio 4.

Like Tony, I viewed the programme as a hopelessly one-sided critique of the economics profession. Still, it was useful in the sense that it packed all the regular criticisms about economics into one short piece. I agree with most of what Tony wrote but I want to take a different approach because I think it’s worth engaging a bit more positively with the criticisms raised.

My sense is that a large number of undergraduate economics students are unhappy with the way that subject is taught and many would echo the criticisms in this programme. For this reason alone, these concerns are worth addressing constructively. Even if some of the criticisms reflect misconceptions that students have about economics, this raises questions about whether we should allow space in the curriculum for these misconceptions to be discussed and addressed.

The First-Year Student Problem: Economics and the Real World

A key part of the programme features economics students expressing their profound disappointment at what is (and is not) going on in the class room during their first year. For example, this student from Cambridge says:

It was very clear to me, a first-week economist student, how the economics profession has gotten itself into this strange cul-de-sac

Chakrabortty then editorialises that students were being ‘instructed by their professors to ignore the meltdown’ based on the following story from the same student:

It felt like doing economics was being asked to go into a bubble. Sometimes our tutors actually said out loud ‘Don’t try to think about this in relation to current events or don’t try to think about this in relation to the news headlines right now … Go into the library and do your problem sets.‘

Then there’s this, from one of the founders of the Post-Crash Economics Society at the University of Manchester:

Economics was in a state of uncertainty and flux and in a place where it didn’t have all the answers and then to come to uni and find people saying ‘this is how it works, learn it, recite it and we’ll do a multiple choice test for you at the end of the year’ and one of the things I will never forget is when an economics student came up to me and said ‘I feel so embarrassed when my friends and family say `What’s going on with the financial crisis?’ and I just don’t know what to tell them. I don’t feel anything I have learned can explain to them satisfactorily what’s going on.

Chakrabortty’s own attempt to demonstrate the weakness of the undergraduate syllabus is unintentionally hilarious, and significantly less compelling than the explanations offered by the students. He explains that students don’t know ‘basic stuff about the economy’ because they don’t do well on some ‘basic yet fun questions’ that he asks, such as ‘What is world GDP?’ and ‘When was the Bank of England nationalised?’ Of course, these questions are not basic or fun or things that anyone needs to know off the top of their head.

It is easy enough for economists to dismiss much of the above as generic student whining or the ramblings of a confused journalist with an agenda. In what version of the world would staff not be telling students to do their problem sets and study material for tests? And ask yourself, if rote learning of dates and numbers did feature heavily in the economics syllabus, do you reckon Chakrabortty would have applauded such an approach?

More seriously, of course students would like to get straight to the parts of the subject that they figured would be interesting when they signed up. But economics is hardly unusual in asking students to learn basic skills first before building up to more complex topics. For example, I teach a third-year module that focuses at length on banking crisis but even within that quite advanced course, it takes a number of weeks of essential nuts-and-bolts material before we cover how crises occur and their effects.

I suspect you could probably find first-year computer science students at most universities complaining how they were hoping to hear about robots and artificial intelligence and are now bored by a steady diet of maths and C++ programming or first-year biology students moaning about not hearing anything about nanotechnology. But it’s unlikely the BBC would make a documentary about them.

All that said, we as economists have to accept that the popularity of these complaints isn’t just bad luck. Economics really is different from other subjects. You don’t hear stories about AI or nanotechnology on the news every day and when there’s a recession, biology students aren’t asked by their friends and family to explain what’s going on. Economic events are part of the fabric of people’s daily lives and those who to study economics in university hope it will help them understand the important events going on in the world.

In this sense, I think the students have legitimate complaints about first-year economics programmes. Yes, it is crucial to give students a grounding in the analytical methods necessary to be a good economist, but we also need to devote more time to connecting to the real world events that are going on around us.

Introductory economics should be linking directly every week with something that is going on in the real world, whether it be some event illustrating basic economic principles or perhaps a release of macroeconomic data. This may be difficult for hard-pressed individual staff members to put together but with major textbooks now backed by interactive websites, there is no reason why we shouldn’t expect these websites to be providing lots of this kind of material.

Similarly, rather than boring students with ‘introductory quants’ classes that teach statistics in a dry fashion, students should be learning how to get their hands dirty with real-world data from day one, working with spreadsheets and preparing graphical presentations of data describing current events.

Another fair criticism aired in this documentary is that economics programmes don’t focus enough on past economic events. Economic history provides a crucial context for understanding how we ended up with the economy we have today and I think some amount of economic history should be part of every year of the economics syllabus.

So I can see both sides here. But, overall, I think the onus is on the economics profession to work harder to get the real world into the classroom.

Boring Abstract Theory?

The students are almost certainly right about the lack of real-world material in first-year classrooms. But what really jars with them is what they view as the abstract nature of much of the material they are asked to study. Another Manchester student from the documentary says:

I was amazed at what the economics was that I was learning. I didn’t recognise it to be what I understood as economics at all. And I assumed there would be discussion and I assumed we would be talking about the real world but it was just incredibly abstract theory and only one theory which didn’t help explain anything at all.

The most common complaint — given a thorough outing in the BBC programme — is that real people are complex social creatures and not the cold analytical calculating machines described in the classroom models. Hence, the logic goes, these models are clearly useless.

Listening to this, it struck me that economists over-do the ‘rational choice maximisation as the core of economics’ shtick with their first-year students. Most of the key insights of economics do not actually rely on people being optimising computers.

Take introductory micro, for example. We can derive models of supply and demand from first principles based on rational choice theory. But the basic insights of the model don’t rely on these assumptions. Do we need to assume hyper-rationality to argue that people probably purchase less of a good if its price goes up? Are we assuming people are maximising computer-like drones if we argue that the price of something going up makes it more attractive to supply it?

Similarly, undergraduate Keynesian macro is largely based on relationships that require minimal appeal to optimising behaviour, with examples being simple consumption functions, capital investment depending negatively on interest rates and prices being sticky. (This relatively weak link to optimisation is why many academic economists don’t like this stuff but it is undeniable that it still forms the core of undergrad macro at most universities).

But when we do use optimisation, how should we respond to ‘People don’t act that way so this model is false and therefore useless’? I think this is a critique that economists don’t do nearly enough to address when we discuss our theories with students and non-economists.

Why don’t models in economics describe how ‘real people’ act? The answer is that human beings are the most complex thing in the world — collections of flesh and blood directed by an operating system more complicated than the most advanced computers could ever be — so economic models could never be literal descriptions of how people behave.

The purpose of theory in economics is to use a model that is literally false but could help us get a better (if still incomplete) understanding of the world than we would have if we weren’t using the model to organise our thoughts. Rather than spend days modelling precisely what’s going on in the brain of the person buying a loaf of bread, the supply and demand models helps the student to think through what might happen to the price of bread if the government raises VAT, or demand for food goes up in China or there is a drought in grain-producing countries. And that stuff is actually pretty useful.

These points argue for allocating a bit less time to teaching theory in first year and spending a bit more time articulating how we view the role of theory and why it is useful. Some time spent on the history of economic thought, so students can see how we ended up using these particular models, would also be beneficial.

Economists as Neoliberals

Moving beyond the ‘abstract and out of touch’ material, Chakrabortty’s programme also focused on the idea that economics departments are devoted to promoting right-wing ideas, with academics consistently preaching the idea that free markets always work best.

The odd thing about this is that an enormous amount of undergrad economics education focuses on the many ways that free markets fail to produce the best outcome. After the standard treatment of supply and demand, most of the rest of undergrad microeconomics focuses on the many reasons why free and unregulated markets produce bad outcomes. Industrial organisation focuses on problems due to imperfect competition, public economics focuses on externalities and inequality, advanced micro focuses on problems caused by asymmetric information, game theory focuses on co-ordination problems and so on.

In addition, mainstream macro at the vast majority of universities is distinctly Keynesian in focus, emphasising the sub-optimality of a laissez faire approach and the need for systematic use of fiscal and monetary policy to promote macroeconomic stability.

It turns out that economists tend to vote in line with these widely-taught reservations about free markets. As the recent, widely publicised, paper by Marion Fourcade, Etienne Ollion and Yann Algan points out ‘Politically, economists vote more to the left than American citizens’.

In fact, the economics textbooks are so full of arguments for intervention, it might be surprising that economists are not a bunch of radical interventionists. So why aren’t we? I think the answer lies partly with many economists acknowledging the limitations of our own theories.

It’s one thing to know that a market with a small number of firms may produce sub-optimal outcomes. However, it is much harder in practice for a government regulator to know precisely what the socially-optimal price for various products should be at all points in time. In theory, governments may be able stabilise the economy using fiscal policy but in practice, an economy can often already in recession by the time government notices it and then takes action.

More generally, government policies are not simply the actions of the perfectly informed benign social planner of the economics textbooks. Rather, they are the outcome of a complex and politicised process in which the government only ever has incomplete information and in which those involved in policy formulation (whether they be lobbyists or public sector unions) may seek to manipulate the process for their own narrow interests.

In other words, designing interventionist policies to offset the problems due to free markets comes with its own set of problems. Some economists focus on these problems more than others depending on their ideological slant. But, ultimately, when at its best, the profession takes an evidence-based approach to assessing the impact of policy interventions and I believe that improvements in econometric methods are promoting an evidence-based approach to policy assessment.

So that’s the nature of debates within economics about free markets and the role of government, at least as I see it. But Chakrabortty’s programme misses this subtle debate in its entirety. Its star witness for the prosecution of economists as free market capitalism promoters was Victoria Bateman of Cambridge Economics department.

Victoria contributed the following:

At the fundamental root cause of the crisis is the belief of economists in the free market capitalist system and the result of this growing faith, that really began in the 1980s with the rise of Margaret Thatcher and with Reagan in the US, the result of that belief was a liberalisation of markets, privatisation, the rolling back of the state, deregulation of the financial sector. And so we began to experience full-blown capitalism. That it would be set forth free reign and the result would be low unemployment, inflation that was under control, respectable even high economic growth rates. The result was that, on the eve of the global financial crisis, economists were looking ahead and imagining a rosy future.

I genuinely do not recognise the economics profession in this description, nor indeed the description of the actual economy. In light of what we know from economic history, could the UK economy of the Tony Blair years — with its national health care and social welfare system — credibly be called ‘full-blown capitalism’?

Truth is, Thatcher and Reagan were not people that influenced the thinking of mainstream economists. Rather, they were politicians that were heavily influenced by the views of people like Milton Friedman and other economists from the so-called Chicago school. However, the Chicago school’s viewpoints were never representative of the ‘median economist’ and said median economist’s viewpoints on market liberalisations and regulation are generally boringly subtle.

Ultimately, mainstream economics can be used by either right or left-wing groups to make their points. Even if it appears that right-wing groups are very vocal in citing economic theories to support their viewpoints, equating the whole profession of economics with a right-wing political movement is misleading and unfair.

Methodological Narrowness?

While the criticism that economics is dominated by right-wing agenda is unfair, a related charge that is closer to the truth is that the profession is too narrow in its methodology.

Here the criticism comes in two brands. First, the profession is too focused on a specific narrow quantitative methodology. Second, the curriculum doesn’t focus enough on various ‘heterodox schools of thought.’

I have a lot of sympathy with the first point and less with the second. I do think economists are perhaps overly in love with their preferred set of methodologies and perhaps fail to see that mixing them up with the kind of broader knowledge I’ve discussed above could produce more rounded students. Even more critically, I think macroeconomists in particular are reluctant to admit to undergraduates (and sometimes to themselves) the full extent of the problems with their preferred modelling approach, based on rational expectations and optimisation.

Still, the fact that there are weaknesses in many of the theories taught at undergraduate level, does not mean there is a ready-made alternative set of models that work better.

For example, it is clear (to me anyway) that the standard rational-expectations-based model of asset pricing does not work for a wide range of important heavily-traded financial assets and that financial allocation decisions by households are some way different from what a textbook optimising model would say. This opinion is held by many economists so behavioural financial economics is a thriving field. There are plenty of insights from this research that can be distilled down and taught at an undergraduate level.

However, what behavioural economics has not yet achieved is an agreed core of principles and methods that are easily distilled and taught and which are proven to have general application. A ‘horses for courses’ approach to figuring out which kind of behaviour appears to explain which kind of ‘anomaly’ (economics for ‘stuff our models can’t explain’) can be insightful but it doesn’t provide an alternative foundation upon which to rebuild a discipline.

In relation to ‘heterodox’ economics, I think many of the concerns raised by the Manchester students and other groups would be addressed by more focus on history of economic thought, both as a stand-alone module and also as something addressed within modules on specific subjects. Many of the historical economists that the protestors view as systematically excluded from the curriculum can be given an airing and their ideas put in context.

But beyond that, I think it’s reasonable to decide that the curriculum doesn’t have to devote time to every ‘school of thought’ that was once fashionable. Most of the various schools that get mentioned in these debates turn out to be various forms of old-fashioned macroeconomics. But there really are more useful things for students of macroeconomics to learn about than Karl Marx’s labour theory of value or the Cambridge capital controversies. Sometimes, the profession moves on for the right reasons.

Prediction as the Litmus Test

Most of the complaints about economics from the Post-Crash society would have been accurate about any economics curriculum over the past few decades. They are so virulent now, however, because the global financial crisis changed many people’s view of economics. To many, the failure of mainstream economics to predict or prevent this crisis indicates that the subject has failed and needs to be fundamentally re-thought.

By definition, this specific critique is a post-crisis phenomenon but it can also be seen as a variant on a longer-running viewpoint that evaluates the success of economics on the basis of its ability to predict macroeconomic events, often likening it to a highly ineffectual version of weather forecasting.

This is an area where the public image of economists as masters of the universe with a superiority complex (as discussed by Fourcade et al) turns out to be misleading. The public focus on prediction in economics boils down to macroeconomics: Can we forecast business cycles, particularly the more extreme booms and busts? And here, the expectation levels of the general public (and first-year undergrads) about what is possible are way out of line with those of practicing macroeconomists.

People joke about weather forecasting but those guys have it easy. They pretty much know the underlying laws of physics that drive weather patterns, which is a great place to start. But solving millions of nonlinear differential equations and feeding them the correct initial conditions turns out to be tricky so they have to work on getting manageable approximations to the underlying true model.

Forecasting the macro-economy, however, is a completely different kettle of fish. We don’t know the underlying equations that determine one person’s economic behaviour and couldn’t even begin to imagine how we would ever write down the ‘right model’ for data generated by aggregating over the behaviour of the 7 billion people on the planet.

Looked at this way, expectations for macroeconomic forecasting should be set very low. And indeed, it turns out that those macroeconomists that devote their career to providing forecasts are pretty lousy at it. In fact, there’s some evidence that those who appear to do better than others might just be lucky.

The reality is that most practicing macroeconomists don’t participate in forecasting at all nor is their research focused on improving forecasts. So posing what many regular people view as the crucial question by which you judge macroeconomists — ‘Did you forecast the global recession?’ — is regarded my most macro people as a sign that you just don’t understand what they do.

So what use are macroeconomists then? One answer is they can explain important facts (such as how spending equals income in a closed economy) or important patterns in historical data (such as key trade-offs between various macro variables). Theoretical models and empirical analysis can also be useful for ‘What if?’ analysis i.e. if X happened, then what usually happens to Y? That kind of analysis isn’t always useful for forecasting (it may not be easy to forecast whether X is going to happen) but it can be useful for understanding major events (when X happens, we can recognise why it is having a particular impact) and for policy formulation (if X tends to lead to bad outcomes, then perhaps the government can try to prevent X from happening).

This might all sound a bit limited but it has its uses. For example, U.S. macroeconomic policy making in 2008/09 was certainly much better than it was during the Great Depression and, bad as things turned out, it would almost certainly have been far worse for the American public if the Federal Reserve and President had the macroeconomic beliefs of their equivalents from the 1930s (which is not to say that many influential people in Washington don’t still have these beliefs).

The Financial Crisis as a Defining Failure of Modern Economics

Which brings us to the financial crisis. Funnily enough, this is perhaps an area where the kind of critiques are furthest off base. The documentary carries commentary from economists such as Steve Keen arguing that mainstream macroeconomics pretty much ignored the role of money and banks.

I don’t think this is a fair assessment of pre-crisis economics. None other than Ben Bernanke became a leading figure in the profession via his analysis of the role of banking problems in the Great Depression and did plenty of work on the various the ways that banks and credit affect the economy. The mechanics of how banking crisis occur were well articulated in models such as the Diamond and Dybvig model from 1983. The much-lauded work of Robert Shiller had also placed the idea that financial markets were much too volatile to be considered fully rational centre-stage in debates in the macro and finance communities. While published in 2009, most of the research underlying Reinhart and Rogoff’s This Time Is Different, detailing eight centuries of financial crisis, reflected research undertaken and published prior to the crisis.

In this sense, the economics profession was not lacking the theoretical tools or historical examples to understand how financial crises occur and why they have such negative effects. What it was lacking was a widespread misunderstanding of the specific mechanics of how this crisis operated.

While similar in many ways, each financial crisis turns out to be subtly different from its predecessors. Often this is because economists have learned from previous crisis and governments have introduced policies to prevent these specific types of crises re-occuring. For example, thanks to deposit insurance, this modern financial crisis did not see spates of retail bank runs with queues of depositors around the corner (Northern Rock being the dishonourable exception — take a bow Mervyn King).

However, the global regulatory system in 2008 was in no way ready to deal with a crisis caused by complex financial products that many regulators did not understand and a level of global financial inter-connectedness that had never previously prevailed. And despite the lessons now learned about how this crisis occurred, it would be foolish to argue that some other kind of financial crisis — with some new defining features — won’t emerge again in the future. Perhaps again, the crisis will be declared a defining failure of economics by those too young to remember it was always like this.

Greenspan’s ‘Model’

Chakrabortty’s documentary gives airtime to the idea the financial crisis showed that ‘economists’ models’ were wrong. On this topic, there seem to be two different types of ‘model failure’.

The first is the type of model failure that the programme opens with: Alan Greenspan in 2008 saying he had

Found a flaw in the model that I perceive is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works, so to speak.

(Chakrobortty — a fan of facts — gets his facts wrong in saying that Greenspan was head of the Fed when he made this statement. He had stepped down almost two years earlier.)

Greenspan went on to say

I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organisations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms

Greenspan held an incredibly powerful position and Chakrobortty notes he was called ‘the Maestro’ by some. Hence, he is held up as an example of how economists thought. But this isn’t how the world works. Alan Greenspan was not an academic. He was a consultant who leveraged his substantial Washington connections into an appointment as Fed chairman. And his positions on economics were very far from the mainstream.

I worked for Alan Greenspan from 1996 to 2002 and met him quite a few times. He is a man of many talents but it’s an understatement to say that his approach to economics was idiosyncratic. It was an interesting combination of obsessive analysis of high frequency economic data and extreme right-wing views picked up from his time as part of Ayn Rand’s ‘inner circle.’ Hard to believe as it may be, the most powerful economist in the world held views that were very far from those taught in mainstream economics degrees.

There seems little doubt that Greenspan’s views on financial regulation had some influence and contributed to a highly complacent attitude towards the dangers posed by the financial sector. Even if didn’t necessarily reflect mainstream academic thinking on the financial sector, it is good news that this complacent ‘model’ that sees financial institutions as self-regulating has hopefully been dealt a lethal blow.

Quantitative Macro Models of the Financial Sector

Then there’s a completely different type of model: A quantitative model with equations. Something that can be put on a computer and used to do scenario analysis or provide bad forecasts. Like Tony, I think Bank of England chief economist, Andy Haldane, is referring to this kind of model when, in the documentary, he talks about ‘it turns out that the model we had was false.’

Andy is certainly right that the official macroeconomic models used by central banks prior to the crisis had very limited details on the role of the financial sector. And even those academic models that did feature such a role (such as the Bernanke-Gertler-Gilchrist financial accelerator model ) did so in ways that were so stylised they could never have been used to forecast a financial crisis.

The positive spin doctor in me would point out that there is lots of work being done now on quantitative models featuring interactions between the financial sector and the wider economy. One can point to a large body of research on integrating banking sectors into ‘DSGE’-style quantitative macro models as well as smaller models by super-smart people like Markus Brunnermeier and Hyun Song Shin.

Still, the realist in me suggests that we are still a long way away from having models that can be used to tease out the full range of mechanisms that could produce the next financial crisis. As with macro forecasting generally, anyone working in this area ends up becoming very humble in their ideas about what is feasible. I think the best we can hope for is that this kind of modelling can help us understand the mechanisms through which modern financial systems influence the wider economy. This could help us design better regulation and stave off the next crisis for longer than it would be if these issues were being ignored by economists. And that’s not a bad aspiration for a research programme.

Another aspect of the documentary that didn’t ring true to me was the idea — promoted by Steve Keen — that there are lots of alternative quantitative models of the role of credit in the economy that are very useful but just ignored by the mainstream for ideological reasons. I don’t see it this way.

So-called ‘heterodox’ quantitative models such as stock-flow models or Keen’s own brand of post-Keynesian macro are really just standard quantitative macro models with some tweaks. They are also subject to the exact same critiques about abstract theorising and unbelievable assumptions as standard models and are just as technically difficult. There are reasons why I think these models are not particularly popular: The stock-flow models have very useful detail on the structure of the economy but tend to be very unstable and hard to work with; Keen’s own models are highly stylised and seem to me to feature odd definitions and assumptions. In other words, I don’t think the reasons these models are unpopular with other economists revolve around ideology.

What of the idea that what students really need to know is deep in Marx or Minsky? Well you won’t learn much about Collateralised Debt Obligations in Marx. And if Minsky’s argument was that financial crisis are an innate part of capitalism, would economics be a branded a success when the next crisis occurs because we had been teaching all our students about Minsky and that such a crisis was inevitable? I reckon students would be better off reading Haldane’s speeches or having a go at reading Brunnermeier and Shin than ploughing through Marx.

Conclusion

I reckon nobody’s reading at this point, so I’ll just say what I think to keep myself happy.

The world economy is more complicated than any of us can understand and getting more so by the day. There are no magic formulae for understanding it and it takes many years of learning about it to even understand which kinds of approaches to thinking about the economy are useful versus which kinds are not. Undergraduate students are really not the best people to be designing a syllabus for a subject that is so bloody complicated.

But the truth is that many students are dissatisfied and a significant amount of their complaints are well-founded. With all the attractions of the information age available to them, students are more demanding than ever and can be turned off a subject more quickly in the past. We need to work harder to show students how economics connects with the real world and we need to explain to them how we think and why we think that way.

Noted for Your Nighttime Procrastination for December 19, 2014

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Equitable Growth--The Equitablog

Over at Grasping Reality: Hoisted from 2010: David Blanchflower: Welcome Back to 1930s Britain

Ed Luce: Too Big to Resist: Wall Street’s Comeback

Alan Blinder: ‘What’s the Matter with Economics?’

David Jolly: Swiss National Bank to Adopt a Negative Interest Rate

Paul Krugman: Switzerland and the Inflation Hawks

Nick Bunker:

Wealth inequality and the marginal propensity to consume

Nick Bunker:

Qualitative editing

Nick Bunker:

Weekend reading

Plus:

Things to Read at Night on December 19, 2014

Must- and Shall-Reads:

Rick Mishkin and Eugene White:

"We find that there were precedents for all of the unusual actions taken by the Fed. When these were successful... they followed contingent and target rules that permitted pre-emptive actions... but were combined with measures to mitigate moral hazard..."

Barry Eichengreen:

"The best thing the ECB could do to encourage fiscal consolidation and structural reform is to banish the specter of deflation... [by] full-bore quantitative easing can do that. Those who object that such audacity would discourage fiscal consolidation and structural reform should consider what deflation would do..."

Robert Huebscher and Jeremy Siegel:

Fair Value for the S&P 500 is 2,300

Joshua M Brown: