T. Carlos Anderson's Blog, page 5

December 9, 2020

Grace from the Rubble – Book Review

A generation ago, a bombing in Oklahoma City shocked an entire nation. An intentional truck-bomb blast killed one hundred sixty-eight people and injured more than six hundred at the Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995. The event is the deadliest domestic terrorist attack in US history.

[image error]

Grace from the Rubble gives a thorough sketch of the build-up to the fateful day. If you were born after 1985 and have never read up on the event, Grace provides an overview of the calamity with personal touchpoints. The crux of the book, however, is the unlikely friendship that develops between Bud Welch, whose daughter Julie Welch perished in the blast, and Bill McVeigh, father of perpetrator Tim McVeigh.

Author Jeanne Bishop is a trained journalist, a decades-long public defender, and crime-victim survivor – all of which makes her uniquely equipped to tell this story. Her first book, Change of Heart, details a personal tragedy: the murder of her younger sister, three months pregnant, and brother-in-law, perpetrated by a wayward teenager during a robbery gone awry. The memoir focuses on the author’s journey of acceptance of the event and her reconciliation with the imprisoned offender – years after the crime.

Jeanne Bishop recently spoke to me by telephone from her Chicago-area residence. She told me about her transformation, inspired by her Christian faith, from wanting her sister’s murderer to rot to death in prison to advocating for prisoner rehabilitation and the abolition of the death penalty. “God’s taught me that every life is precious.” For Jeanne Bishop that includes teenagers who commit serious crimes, often deemed unworthy of rehabilitation in this society.

Her work as a public defender and her involvement in abolition advocacy often pits her against capital punishment supporters. “Every time I’d get into a debate about the death penalty, people would say ‘If it was your family member who was killed, you’d want the death penalty for the murderer.'” She says her opponents often have no idea that she is one of those family members.

Those debate experiences compelled Bishop to write her first book – “I wanted to tell my one small story of my sister” – in order to provide a counternarrative to the commonly-held idea that retributive punishment is a naturally part of the healing process for crime-victim survivors.

Through her advocacy work to abolish the death penalty, she met a kindred spirit in Oklahoman Bud Welch. They’d speak as panelists at the same criminal justice reform conferences – two crime-victim survivors, she of a horrific family murder by a sixteen-year-old kid fascinated by guns and he of a barbaric attack by an anti-government, militia-movement extremist.

For years, Bishop heard Welch speak from podiums and in personal conversations about his connections with the elder McVeigh. The implausible Welch-McVeigh companionship gave birth to her second book, Grace from the Rubble. “I wanted to write about how we respond to evil. We have to learn how to respond to that other than with more evil.”*

In the immediate months after his daughter Julie’s death in the rubble, Bud Welch’s life consisted of three excesses: cigarettes, booze, and vivid images of revenge. After reeling for six months, Bud intentionally focused in on how he might feel if and when Timothy McVeigh was executed. Through splitting hangover headaches most every day for a month, Bud Welch finally decided that killing a killer made no more sense the original heinous act. Bud Welch, a Roman Catholic, cut back on booze and smokes, and began to let the thoughts of revenge go. Instinctively, he knew that McVeigh’s eventual execution would do nothing for his own healing process.

He happened to tell an AP reporter of his desire that McVeigh not be executed. The story went viral: The father of an Oklahoma City bombing victim who didn’t want McVeigh to fry. The Washington Post quoted Bud at the time: “That was why Julie and the other one hundred sixty-seven people were dead – because of vengeance and rage. It has to stop somewhere.”

A Roman Catholic nun in the death penalty abolition movement happened to read about Bud Welch and his opposition to McVeigh’s execution. The nun invited Bud to come and speak to her advocacy group in Buffalo, New York. Bud agreed, and he had a favor to ask. He knew that Bill McVeigh, also a Roman Catholic, lived in nearby Pendleton, New York. Bud asked the nun if she’d set up a meeting between him and the elder McVeigh.

The rest of this improbable story is in the final chapters of Grace from the Rubble. Kudos to Bud Welch for pursuing an encounter with Bill McVeigh, and kudos to Jeanne Bishop for sharing their story with the reading public. Their story is one of restorative justice – healing the harm done by crime beyond what happens in the courtroom or in a prison death chamber. **

At the end of our interview, I asked Jeanne Bishop to share her thoughts on restorative justice. “The beauty of restorative justice is that it allows for people to come together in their humanity with an opportunity to redeem a tragic event.”

* Quote from article by Norman Jameson, Baptist News Global, “ 25 years later, grace and forgiveness still rise from rubble of the Oklahoma City bombing – Baptist News Global .”

** Tim McVeigh was executed on June 11, 2001, the first federal execution since 1963.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

December 2, 2020

Dopesick – Book Review

Beth Macy’s Dopesick is one of many revealing books on the opioid epidemic, with Sam Quinones’s Dreamland being the most prominent. You’ve made your way to my blog . . . which means there’s a good chance that you are a reader. Macy’s book goes deep on personal stories of pain and tragedy from Appalachia, the crucible of the crisis. It’s not an uplifting or hopeful read, but to ignore its details is akin to burying your head in the sand while this crisis guts out a portion of American society, leaving numerous families – like yours and mine – devastated in its wake.

Addiction surfaced onto my radar when I was a twelve-year-old kid. My dad, who worked as a chaplain at a drug treatment facility, brought my eleven-year-old brother and me to an Alcoholics Anonymous public speaker meeting. While the name of the speaker escapes me more than forty-five years later, I remember that he was a retired major-league baseball player who said that alcohol cut his career short. In that mostly full high school auditorium, my nascent self-identity – partly based in the importance of playing sports – was tinged by the introduction given by the fallen but redeemed athlete to the human predicament of addiction.

My dad – now in partial retirement – still works in the field of addiction. Last Christmas, he sent Dopesick my way as a gift. I’m grateful that he introduced me so many years ago to this intriguing and beguiling subject about which I’m still learning. Dopesick taught me plenty in its 350-plus pages.

Macy breaks down the opioid epidemic in the following fashion. Big pharmaceuticals (led by Purdue Pharma) produce opioids (like OxyContin) in the late 1990s and push their pills like crazy as the new panacea for pain, claiming for them a low incidence-rate of addiction; a number of doctors over-prescribe these pills helping create addicts ranging from teenagers to seniors; federal government finally cracks down with significant regulation in 2016; and today, heroin, much cheaper and more readily available than opioids, fills the void created by the crackdown.

There’s your quick-and-dirty summary of the crisis that’s not even close to being over. In 2016, more than 100 Americans died each day from opioid overdose. This rate increased in 2017 and epidemiologists say it will continue to increase into the new decade, possibly more than doubling the 2016 rate.

For many years, I thought of drug and alcohol addiction – now also called “substance use disorder” – as binary: you either were afflicted with the monkey on your back or you weren’t. I now understand that there are levels and layers in between the two ends of the one continuum. The potency of opioids, however, can anchor most users – even first-time recreational users – at the continuum’s far bleak end.

Dopesickness, Macy explains, is the underside of addiction: vomiting, shakes, sweats, diarrhea, nausea, paranoia, and the feeling of skin-crawling – when there’s no more drug. More so than the craving for another high, the fear and avoidance of dopesickness is why the afflicted rob family members and banks, break into pharmacies, and frequent urban centers like Baltimore to buy cheap heroin off the streets.

Macy, on page 106 of the hardback version, summarizes the findings of addiction researcher Warren Bickel. He calculated the nonaddicted person’s perception of the future to be 4.7 years, which greatly contrasts with the addicted person’s perception of the same: just nine days. When one’s comprehension only sees nine days into the future – the threat of a long prison sentence, the strategy of “Just Say No,” and the prospect of sobriety lose their affect.

Macy promotes an adjusted understanding of sobriety – traditionally, the complete abstinence from mood-altering substances – due to the severity of this crisis and opioids’ insidious ability to enslave its victims. Successful medication-assisted treatment (MAT) – the use of maintenance drugs like methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapies, including 12-Step programming – can typically last up to five years. In some A.A. circles that favor the traditional understanding of sobriety, MAT patients can be stigmatized.

Humans will go to great lengths to avoid pain, whether it be physical, emotional, or psychic. Opium, like alcohol, is a natural remedy that helps mitigate pain, but the beast of addiction lurks on the other side of its attractive coin. In the early 1800s, scientists first refined morphine, ten times stronger than opium. Toward the end of that century, heroin was introduced, at double the strength of morphine. Both drugs were touted as non-addictive by early proponents and widely available. One hundred years later, OxyContin – a reformulation of oxycodone (originally compounded in 1917) – received the same type of “wonder-drug” roll-out: a non-addictive panacea, appropriate for any type of patient – not just cancer patients in hospice care – seeking to alleviate pain.

Again, multiple books published in the last five years break down the opioid crisis. If you’ve not read any, Dopesick is a good place to start. Macy’s skill is her reporting that reveals the personal and societal tolls that this crisis is reaping in this country where it’s much easier to get addicted than to secure treatment.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

November 22, 2020

How To Be an Antiracist – Book Review

If you caught the final presidential debate, you heard Donald Trump describe himself as “the least racist person in the room.” The president wasn’t aware that this type of antiquated statement now serves as a red flag, waived by its claimant, to nullify such description.

A scholar and activist, not yet forty years of age, can claim chief responsibility for delegitimizing such statements that come from people, like the president, who attempt to distance themselves from the ugliness of racism.

[image error]

Ibram Kendi’s How To Be an Antiracist hit #1 on the New York Times bestseller list this past summer. Interest in his book and others like White Fragility and Me and White Supremacy peaked after the murder of George Floyd and the shooting of Breonna Taylor. Over one million copies of Anti-Racist are now in print. Kendi is a renown writer and thinker – his earlier book, Stamped From the Beginning, won the 2016 National Book Award for Non-Fiction.

Kendi raises the bar for those truly concerned about the prolonged effect racism continues to wield in this society. For someone to assert “I’m not a racist” no longer suffices according to Kendi and he admonishes such a person to self-identify as an antiracist and to act as one. Some will dismiss Kendi’s ideas as reeking of politically correct wokeness, but I disagree. Kendi has obliterated what previously passed as acceptable, as did US track athlete Dwight Stones in 1973 when he used a new technique – the Fosbury Flop – to set the world record for the high jump. No world-class high jumper has since used the previously preferred Straddle Style technique.

2020 marks new territory – for better and for worse – as concerns racial matters in the US. The Trump administration’s and the president’s permissiveness, in particular, with white supremacist groups has sullied the racial environment. According to a recent Gallop poll, fewer than half of Americans say race relations between Blacks and whites are good – its lowest rate in twenty years. The racially and ethnically diverse demonstrations this past summer in the wake of the Floyd and Taylor killings, however, and the expanding conversation on the history and continuing effects of racism in America tell a different story. There’s regression and advance at the same time for Americans in their understandings about race.

Is there systemic racism in the US? Consider the yay and nay responses to this question in today’s America, mirroring the cultural and political identities that divide so many in this society.

Kendi offers a different response to the question. He writes that “institutional” or “systemic racism” are terms that are too vague. Rather he points to racist policies: decades-long redlining practices that have produced segregated housing markets; 1990s-era crack cocaine criminalization that has contributed to the current mass incarceration of Blacks; standardized testing and its results used by groups to focus on “achievement” gaps rather than opportunity gaps; voter ID laws, many of which are current-day manifestations of Jim Crow-era restrictions.

Kendi says he learned from a young age the stock creed that racist ideas cause racist policies. He no longer stands by this creed and its implication that moral persuasion is the best practice to mitigate racism and its effects. His research showed him that self-interest, more so than ignorance and hate, is the fueler of racism. “Racist power produces racist policies out of self-interest and then produces racist ideas to justify those policies” (pgs. 129-30).

An antiracist, according to Kendi, works to create and support policy that reduces racial inequities. Activists, he writes, do more than just preach, teach, protest, or write op-eds or books. True activists successfully change policy.

Like many of his classmates at Florida A&M University, Kendi was a first-time voter on November 7, 2000. He writes that he and many of his friends at the Historically Black University voted for Al Gore, in opposition not only to George W. Bush but also to Bush’s brother and Florida governor, Jeb, who had gutted many of the state’s affirmative action programs the previous year.

In the weeks after the election, Kendi heard anecdotal reports from numerous classmates that their Black relatives’ and friends’ votes in Florida were either nullified, denied or not counted. Eventually, George Bush was declared Florida’s winner by a mere 537 votes which clinched him the national electoral vote. Florida invalidated close to 180,000 ballots and more than half of these were from Black voters. Overall, Black voter ballots were invalidated at a rate ten times that of white voter ballots in Florida in 2000.

That’s racism in action – policy, practice, payoff.

Is it any wonder that in the two decades since Florida 2000, hundreds of new voter restriction measures have been implemented in dozens of states?

As of this writing, Donald Trump still pretends to have won the 2020 election. A deeply narcissistic self-interest propels Trump’s fantasies as his campaign actively tries to eliminate votes from Detroit, Philadelphia, Milwaukee and Atlanta where Blacks are most populous. As for Phoenix, which only has a 6 percent Black population, the Trump campaign has been comparably silent about their loss in Arizona.

As the president desperately tries to subvert the results of the election, a recent FBI report named 2019 the worst year for hate crimes in the thirty years that such records have been kept. The report labels white supremacy the main culprit.

Kendi’s book is timely. Like me, you might not agree with everything Kendi writes in the book. Countering racists and racism in America is now a full-time job for many of us – Kendi’s main and crucial point. The bar has been raised, and conversation with Kendi is a necessary part of the antiracist’s job training.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

October 22, 2020

Still Better Than Church

The women file past me into the room. They all wear the same bland prison whites, a pullover top matched to loose pants with an elastic waistband. Most of the women are in their twenties and thirties, and not attractive in the conventional sense. Their collective presence jars me, though I do my best to appear nonchalant. The prison unit, a substance abuse felony punishment facility in Texas that offers treatment for alcohol and drug abuse, claims them for seven to twelve months because of drug possession or DWI conviction. A number of the women are missing teeth, due to crystal meth abuse. Some of the women’s faces betray hard decisions and painful memories – of which I will hear when they begin to speak.

[image error]

I’m at a graduation ceremony for Bridges To Life (BTL), a restorative justice prison ministry that joins surrogate crime victims and perpetrators face-to-face. All of the women in the room have completed the ministry’s fourteen-week program that coaxes forth self-awareness, accountability, and restoration by requiring participants to engage in rigorous self-evaluation. Small group discussions allow participants to honestly share their stories with one another. The traditional healing practices of confession and forgiveness are used to help inmates examine the effects of their crimes upon themselves, upon their relationships with family and friends, and upon the relationships their offenses have created with the victims of their crimes. (BTL is a volunteer program that is not part of the prison’s in-house drug treatment efforts, but it buttresses those efforts all the same.)

It’s open-mic for this evening ceremony of graduation. Three questions will guide the women’s remarks: 1) How have you changed in the last fourteen weeks? 2) How do you feel now? 3) What do you want to say to the group?

A woman slowly steps up to the wood podium in front of six neat rows of folding chairs, from where her fellow inmates, ten BTL volunteers, the prison chaplain, and I watch her intently. She tries to speak but can’t as tears well up in her eyes. Immediately, a chorus of fingers snapping in-time and raised in the air – as I’ll learn, their particular expression of support – fills the room. The woman covers her face with her hand and wipes her tears. She takes a deep breath and begins: “For the first time in a long time, I’m living actively and not passively. I feel alive again and my attitude has changed immensely. I’m letting feelings about my past go as I’ve learned I need to forgive myself. I feel important to myself again.” This last phrase jars me, but in a distinct manner from the jarring that internally shook me when the women filed into the room. I feel important to myself again – this particular description, the tip of an iceberg of human darkness and light, sets the stage. I will hear variations on the same theme of transformation for the next seventy-five, tear-inspiring minutes.

Released emotions, more tears, and at-the-ready snapping fingers accompany the ensuing testimonies, each one upon its conclusion met with cheers and applause:

“I didn’t feel like I was worthy of change before, because I came here with a lot of guilt and shame . . . but now I have acceptance.”

“My everything has changed – the way I look at others and the way I look at myself. I’m proud of myself. I haven’t been proud of myself for years.”

“For so long, I hated myself and couldn’t forgive myself. But I feel lighter and freer now. The more I tell people about my weakness, the more restored God has made me feel. I have hope again.”

“Before I started this program, I felt like I was a victim. But when we wrote our letters, it occurred to me that I had harmed other people. I was blind, but now I see.”

The letters to which the last speaker refers are confessional letters of apology to those harmed by the offender’s actions. Letters are written to a family member and a victim of the offender’s crime – the letters are not sent but used for small group discussion in the weekly BTL sessions, for the purpose of the offender claiming responsibility and accountability.

Another woman, who will be the final one of the evening at the podium, lowers her head and fights back tears like so many before her. She then gazes up to the ceiling and takes a deep breath. The finger snaps fade and the room is absolutely still. In a voice quiet yet saturated in determination, the woman speaks the following words of profound self-understanding:

“Because of this program, now I remember who I am . . .”

By this time, I’ve come upon an eye-opening realization myself. I see that what these women are sharing, straight from their souls, is the most beautiful thing I’ve witnessed in some time. Now I remember who I am. As a male in the yet male-dominated twenty-first century world, my first glance at women often times, almost instinctively, is one of simple examination for what my eye understands to be beauty or good looks. I don’t say this in a braggadocious way, but in a truthful and confessional way. The women this night – some with missing teeth, and others unkempt in prison whites and freed from having to present themselves to the outside world – remind me that what binds us together more than anything is the common humanity we carry inside consisting of feelings, emotions, and experiences. All of us are in need of the inner gifts of love, acceptance, and support. Outward displays of possessions, accomplishments, and good looks – all of these having positive attributes – are overemphasized in popular culture, often to the detriment of the more important inner gifts.

The woman who invited me to the graduation, Ellen Halbert, told me ahead of time: “You’ll see. The graduation ceremony is incredible.” She was, and is, absolutely right. Ellen is a crime victim and a prominent restorative justice proponent – the prison unit in Burnet, Texas where we’ve gathered for the graduation, is named for her. A volunteer for BTL since its inception the late 1990s, she shared her story with the women during an earlier session of the fourteen-week program. The women were so moved by hearing Ellen’s story that they insisted she come back for their graduation.

As we linger in the room and share refreshments with the graduates and volunteers, I – a preacher – share with Ellen my evaluation of the evening: “You’re right, Ellen. This was great – better than church.” She smiles and nods her head. She’s seen it before and she’ll see it again: The healing power of shared story and testimony to make a new way forward, for bearer and listener alike.

I originally wrote this post after making the prison visit with Ellen Halbert in July 2017. It was published in the Austin American-Statesman later that same year. In 30 years of ordained ministry, this is the most impactful ministry event I’ve witnessed.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

October 13, 2020

Zooming In on Book Club Discussions

How do you do an author interview and book discussion in the Covid-era? Anyway you can! I recently had a worthwhile exchange on There is a Balm in Huntsville with a dozen readers of a church book club from Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Three of us were on a Zoom connection, and nine others, socially-distanced and masked, shared a speaker phone hook-up inside their church’s sanctuary in South Dakota’s largest city (the church’s Wi-Fi was either overwhelmed or malfunctioning). In an upstairs bedroom at my home in Austin, Texas, I sat in front of my computer’s built-in camera for the Zoomers and palmed my phone in my right hand for the folks participating by audio.

We shared seventy-five minutes of vibrant discussion and interchange on restorative justice, the possibilities of transformation, and prison reform and recidivism.

Lynn, a member of the church’s book club, emailed a few days later: “The story you shared about this man’s journey with life-changing consequences really provided new perspective for me. Thank you for answering our book club questions as I really appreciated learning more from you and WHY you decided this story needed to be told, your time in writing and researching and the ‘factual-ness’ of the information provided. It is hard to know when reading if things have been embellished to ‘make the story’ and your willingness to answer more questions about the people and situation shows your passion and the amazing things God can do for both victims and perpetrators. Thank you.”

Balm tells the unlikely and astonishing story of the development within the Texas criminal justice system of “Victim-Offender Dialog” (VOD), the first state-sponsored restorative justice program of its kind in the nation for victims of violent crime. Within that larger story, Balm details the story of one offender and the parents of a young woman the offender killed in a drunk-driving wreck. They meet at a victim-offender dialog table in a prison in Huntsville, Texas, the offender admitting his grievous mistakes and the parents looking for answers and accountability.

It’s a true story. I wrote Balm in narrative non-fiction style. As the book clubbers from South Dakota can tell you, Balm reads like a novel. I’ve heard from other readers who’ve finished the book in a single day. My Lancaster, Pennsylvania publishers at Walnut Street Books and I are convinced that Balm, when it was published, was the only third-person narrative in the restorative justice genre. There are plenty of good academic books available that explain restorative justice and its practices. Balm, however, is unique because readers learn about restorative justice through the stories of crime-victim survivors and perpetrators.

[image error]

In the year that Balm came out, I had eighteen engagements – at bookstores and churches mostly, and others including a radio interview on Texas Standard and a speaker event at Texas Lutheran University – where I shared the book’s story and answered questions about the writing process. At a few of those events, I shared the stage with two important characters in the book: crime-victim survivor extraordinaire Ellen Halbert and VOD developer and practitioner, David Doerfler. I’m deeply honored to tell Ellen’s and David’s stories of healing, restoration, and bold advocacy in the book.

The pandemic brought an abrupt end to author book events. But all of us are now readjusting. I’m available to meet with your book club or group to discuss restorative justice and its related topics via teleconferencing hook-ups like Zoom (or phone, if necessary!). Thanks to new friends in South Dakota for their openness to new possibilities – for book club discussions and for the healing ways of restorative justice practices.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

October 11, 2020

Restorative Justice – No Need to Politicize It

Like millions of Americans, I watched the Democratic and Republican National Conventions as they ran on consecutive weeks in August. My personal antennae sprung to attention when an aggrieved father, Andrew Pollack, spoke during the RNC about his daughter, Meadow, a victim of the Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Meadow Pollack, a senior, planned to attend college and spoke of becoming a lawyer.

He blamed “restorative justice” for the death of his daughter.

Mr. Pollack is a member of a small club to which no parent wants admittance. The depth of his anger and pain is unfathomable to the rest of us – myself included – who have not lost children to senseless and brutal acts such as the one that took Meadow’s and sixteen other lives, and left seventeen others wounded on Valentine’s Day 2018.

The gunman, Nikolas Cruz, a troubled and disturbed nineteen-year-old (at the time of the shooting) who legally purchased an assault style AR-15, faces life in prison or the death penalty. The COVID pandemic has delayed the start of his trial.

There have always been shootings at schools in the US, the vast majority being situations of personal vendetta or revenge toward a known individual. The 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting marks the beginning of an era of indiscriminate mass shootings at schools. Columbine, in 1999, horrified the nation and called attention to the sheer escalation of such shootings. A national reckoning ensued: Why do these tragedies continue to happen and how is it that teenagers are behind the trigger causing, essentially, child-on-child mass violence?

Many answers emerged: easy access to weapons and weak gun control laws; bullying; movie, TV, and video game violence; isolation; unstable home situations and rising rates of depression and mental health issues among young people.

The post-Columbine period coincided with the cresting of the mass incarceration wave in the US. With only 4 percent of the world’s population, the US today claims 25 percent of the world’s prison population and the highest incarceration rate of any country. Consider that in 1972 there were 200,000 prisoners in the US. Today that figure is 2.1 million. Browns and Blacks are proportionately much more likely to be imprisoned that whites – a process that starts in elementary and middle schools as juveniles are entered into the criminal justice system. What is described as the “school-to-prison pipeline” is recognized as a failed result of an overly punitive approach to misconduct and a marker of systemic racism.

Restorative justice, at its core, is the process of healing the harm caused by crime. South Africa’s “Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” a restorative process, helped the country transition from decades of unjust apartheid to democracy. Restorative justice programs – whether in district attorney offices or prisons – help offenders accept accountability for their actions and bring healing to crime victims.

The implementation of restorative justice principles in school systems is an attempt to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline that traditional discipline approaches (“zero tolerance” suspensions and expulsions) have helped create. Restorative principles utilize preventative measures (mediation or training programs) designed to build skills and capacity in students.

In blaming restorative justice for his daughter’s death, Andrew Pollack alludes to a federal initiative started under the Obama administration, the “Supportive School Discipline Initiative.” A collaborative effort of the Justice and Education Departments, the initiative’s purpose was “to support good discipline practices to foster safe and productive learning environments in every classroom” (press release, US DOJ, July 21, 2011). Breaking up the school-to-prison pipeline was another purpose of the initiative.

Based upon this initiative, in 2014, the Obama administration mandated federal school discipline guidelines, aimed at reducing discriminatory discipline against Black and Hispanic students.

A year prior, in 2013, the Broward County (Florida) School Board adopted its own variation of school discipline reform, called PROMISE Program (Preventing Recidivism through Opportunities, Mentoring, Interventions, Supports, and Education). Troubled and non-compliant Nikolas Cruz, a student in the Broward school system, languished three years in PROMISE Program – eventually exhausting his stay. He was indefinitely expelled in the year prior to the shooting.

In the aftermath of the Parkland school shooting, President Trump seemed to entertain the idea of enhanced gun control laws – a ban on assault weapons, mandatory background checks, a “red flag” law to disarm gun owners who pose risks to themselves or others. Advocating for such changes were a majority of Douglas High School parents who had lost a child in the massacre, along with a vocal group of survivor students at the high school.

The Trump administration, however, backed away from most of the gun control policy changes. Andrew Pollack allied himself with Trump after a White House “listening session” at which, a week after the shooting, Pollack and other parents spoke to the president. Then, in December 2018, the administration issued a school safety report in wake of the Parkland shooting. The report rescinded Obama’s 2014 policy mandate on school discipline, giving school districts the autonomy to determine their own approach to discipline – whether “zero tolerance” policies, the newer policies, or some combination of the two.

The school safety report contained two recommendations that dealt with guns: arming “well-trained” school personnel; and, encouraging states to adopt “extreme-risk protection orders” in order to disarm potentially dangerous individuals, as would a “red flag” law. This last recommendation, possibly, could have kept Nikolas Cruz from purchasing an AR-15.

America has some 35,000 gun deaths a year – the largest number and highest per capita rate of any of the OECD nations (El Salvador has the highest rate, and Brazil the most deaths). Sixty percent of these deaths in the US are suicides. As for school shootings, the US has more incidents and deaths in this category than all other developed nations combined.

Mr. Pollack makes a valid point about the tragic deaths of his daughter and the other sixteen on that horrible day: The shooter should not have had legal access to a gun. Was that the fault of “restorative justice”?

The simpler truth is this: Places, like the US, with more guns will have more gun deaths – whether in cases of domestic violence, violence against police, homicides, suicides, or mass shootings. We have as many guns in this country as we do citizens, a rate that far exceeds that of any other nation.

Until we muster the political will to sign into law sensible gun violence prevention measures, the status quo will continue.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

September 23, 2020

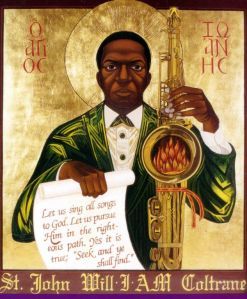

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

John Coltrane released his masterpiece A Love Supreme in February 1965. For those of you unfamiliar with Coltrane’s work, A Love Supreme is as fresh and timeless today as it was more than fifty years ago. Accessibly melodic, Coltrane’s exuberant tenor sax fuses with McCoy Tyner’s teeming piano chords and riffs to produce an unparalleled thirty-three minute session of ascendant and flowing grace.

Give it a look and listen here:

Coltrane’s road to A Love Supreme was anything but straightforward. An incredible talent, he often travelled a wayward path. The hungry ghost of addiction haunted him; he was booted out of Miles Davis’s band in 1957 for continued heroin use, including a near overdose. The close call, however, propelled him to clean up. From the autobiographical liner notes of A Love Supreme: “During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life.” His calling was “to make others happy through music,” which, he claimed, was granted to him through God’s grace.

Coltrane was raised a Christian, and he also sought out other faith traditions after his epiphany. His conclusion: “No matter what . . . it is with God. He is gracious and merciful. His way is in love, through which we all are. It is truly – A Love Supreme – .”

Yes, Coltrane’s credo – like some of his music later in his career – is a bit vague and esoteric. Let me put the credo in other terms, more accessible: love is a sufficiency all its own. In Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good, I detail the societal desire and drive that is never satisfied with enough, always seeking “just a little bit more.” Love is the antidote to the pursuit of more and more; it helps us to be grateful, to relax, to rest, to enjoy, to share, and to know what and when is enough. Love also helps us to do great things – busting our tails in the process – for our neighbor and the common good. Love covers it all.

John Coltrane died of liver cancer in 1967, having completed only 40 years of life on this earth. Forgive the obvious cliché – his music does live on. Coltrane biographer Lewis Porter (John Coltrane: His Life and Music, University of Michigan Press, 2000) explains that Coltrane plays the “Love Supreme” riff (four notes) exhaustively in all possible twelve keys toward the end of Part 1 – Acknowledgement, the first cut on the disc. Love as sufficiency – it covers all we need and then some.

The conclusion of Coltrane’s liner notes: “May we never forget that in the sunshine of our lives, through the storm and after the rain – it is all with God – in all ways and forever.”

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

September 5, 2020

My Jazz Story

I’m not much of a musician, but I love to listen to music – especially jazz. My intro to the American idiom goes back forty years, to the summer of 1980. I labored on a grounds crew at a large Chicago-area hospital, marking the days, eight-shift hours at a time, until college started that fall.

I had recently graduated from a suburban Chicago high school and the Upper-Midwest baked and scorched under a record heat wave. Halfway across the world, fifty-two US hostages lingered helplessly in the American embassy in Tehran. Countless Chicagoland teenagers, me included, bopped their heads to the aggressive bassline of shock-jock Steve Dahl’s parody hit, “Ayatollah.” Based on The Knack’s 1979 chart-topper, “My Sharona,” the parody expressed adolescents’ rage toward Iran’s revolutionary leader whose followers demonstrated in the streets and chanted “Death to America.”

Steve Dahl, in his lyrics, countered with similar bravado: “Don’t get us too upset or we’ll do something nuclear.” But he also chilled out and encouraged his adversary to do the same: “Cool your jets. Meditate. Eat a hamburger.”

Music as language – the capture and expression of emotion – can calm, inspire, incite, humor, encourage, soothe, make you swing, take you back in time, and even heal. At eighteen years of age, my music of choice was rock ‘n’ roll. My brother and I, while lifting weights in our backyard, would turn up Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Bayou Country” as loud as we could on our stereo system. It was pure adrenaline.

Jazz and its more subtle powers introduced themselves to me through my summer job at the large Chicago-area hospital. One day, my supervisor instructed me to go to the supply department, located on the bottom floor of the 15-story hospital building. I carried my boss’s written instructions for my pick-up task – the specific item I was to retrieve is lost to memory. What I do remember: Dim fluorescent lights, a basement-type mustiness, and endless chain-link fence cages – work-space cubicles – separating a sea of desks. The men (it was 1980, I don’t remember seeing any women) all wore bland khaki uniforms as they labored to keep the hospital and its machinery humming. They supplied plumbers, electricians, masons, woodworkers, and various types of construction workers and technicians. I also distinctly remember thinking that a job like this is exactly what I don’t want to have in the future – all the more reason to go to college to equip myself for “better” work.

In this decisive state of mind, I arrived to my destination. Inside a fenced cubicle, a short man sat at a desk, his head keeping time with music. He looked up at me and greeted me with a smile: “What can I do for you, pal?” I held out my requisition note. Both his upbeat demeanor and his music – classic jazz with a bopping bass – startled me. “Give me a second,” he said. “I’ll be right back with the part you need.”

Wow. I had half-expected some grizzled guy, having a bad day at a despised job, to ignore or belittle me and my duty. I was fully prepared for: “What the hell do you want, kid?” Instead, “Jerry” – as the tag on his work shirt proclaimed – interacted with me warmly. By all accounts, he looked to be having a good day and seemed to enjoy his job. Even better to my eighteen-year-old impressionable mind, his eight-hour shift grooved with hip music emanating from the radio on the corner of his desk.

I’ll never forget it – my intro to jazz. I had heard jazz before, but it had yet to make an impression.

[image error]

Jerry’s example – a burst of light in that expansive and dim bottom floor of the building where he worked – showed me that whatever type of work one does can be positively affected by attitude. I might be wrong, but I walked away from his fenced cubicle that day with the impression that his positive attitude was jazz-flavored.

Jazz is hard to define. More than 125 years after its birth in New Orleans, jazz is an incredibly varied genre with worldwide expressions. But when you hear it – you know it. It swings, just like Duke Ellington declared in 1932: “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).” Ellington penned his famous tune between performance sets during a month-long gig in Chicago.

I did go to college. After which I went to seminary, living for a time in South America in order to better master Spanish. I became a pastor and moved to Houston where I had the offer to work bilingually. The jazz and blues shows on Houston’s KTSU became my mainstays and I enriched my personal music library with Miles, Coltrane, Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Oscar Peterson, Houston’s own Jazz Crusaders, and Mark Whitfield – to name a few.

A few years later, we moved to Austin where KUT played jazz every afternoon. My disc collection continued its expansion: Joe Pass, Eliane Elias, McCoy Tyner, Diana Krall, Gary Burton, Arturo Sandoval, Brad Meldau, Eddie Palmieri, Gene Harris.

I’ve now been in Texas for thirty years and currently direct social ministry efforts for a group of churches in Austin. But I haven’t forgotten my Chicago roots.

Over the years, while visiting family in the Chicago area, I’d always tune into 90.9 FM, WDCB, Chicago’s stalwart jazz station. What a gift, a few years ago, when ‘DCB started to stream its signal over the Internet. I now listen just about every day. As I do my work – writing, researching, reading, or driving to a meeting or event – my world is jazz-flavored. Jazz makes my world lighter, fuller, and richer – with a touch of swing.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

August 23, 2020

Peter Steinke’s Uproar

Pete Steinke authored fourteen books, and at the time of his unexpected passing in July 2020, he harbored plans to write a few more. As I’ve detailed in the two previous posts in this series, Pete was not only a pastoral colleague and good friend of mine, but also a writing mentor. He was one of the most well-read persons I’ve known. An old schooler, he’d cut out periodical articles or copy important sections in books on the two topics I’ve written on – the interplay between inequality and egalitarianism, and restorative justice – and send them to me via the US Mail.

Every mailing offered new insight, just like conversation with Pete did.

[image error]

He accumulated an expansive share of wisdom in his eighty-two years, and fortunately for us, much of it is distilled in his last published work, Uproar: Calm Leadership in Anxious Times (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Two of his gifts were synthesizing varying ideas into the same space and adaptation of those ideas to current contexts.

All of his previous books were written for church folks, and, especially after his introduction to Bowen family systems in the mid-1990s, focused on leadership. With Uproar, however, Pete desired to take his well-honed theories on human behavior and his experience as a church leadership consultant to families, groups, and organizations beyond church walls.

Uproar surprised me when I first read it. I was familiar with the main ideas – non-anxious presence, narcissism’s erosion on a leader’s abilities, self-differentiation – these weren’t the surprise. Pete took on the big pink elephant in the room, and I was pleasantly surprised that his new publisher didn’t stifle his voice. The big pastel pachyderm was and is the leadership exhibited by the 45th president of the United States.

Don’t get me wrong. Trump is not the main focus of Uproar, but his narcissistic style of leadership – the need of an adoring audience, the use of lies and misinformation, the inability to suffer criticism – is something Pete saw multiple times in large-egoed pastors of congregations mired in deep conflict.

Pete writes that like some of these narcissistic pastors he observed, Trump is a master artist and that his admirers are model enablers. “Narcissistic functioning is a systemic problem . . . The system is composed of two needy parts, each dependent on the other. This system exists where a self-absorbed and charming leader becomes the object of others’ devotion.”

Chapter 9 of Uproar delves into the Greek mythological tale of Narcissus. Pete reminds us that Narcissus admired his own image in a pool but despaired because he couldn’t possess the image at which he unceasingly stared. Distressed, he eventually fell into the pool and drowned, never to be seen again.

From pages 98-99 of Uproar: “We have been witnessing a strong measure of narcissistic functioning from Donald Trump. When someone has to use hyperbole to magnify achievements, exaggerate numbers beyond reality, and boost self-importance at the expense of others, the person displays a weakness, an immaturity, and a low sense of self. If these behaviors were true of our children, we would be worried about their level of self-esteem, no less their mental states.”

Reinforcing supply – adoration, fawning, praise – keeps a narcissistic leader in power. In this type of a system, there is little differentiation between the adorers and the adored. This is why Trump could get away with, as he arrogantly claimed before being elected, shooting someone in the middle of 5th Avenue in New York City. None of his ardent followers would hold him accountable. They are fused together in lock-step.

This type of leadership doesn’t perform well during emergencies, much less during crises. Why? Because of the worst tendencies of group-think. Zero space between a leader and his or her minions, literally, leaves no room for options or solutions that originate outside of the leader’s own perspective. To wit, Trump’s leadership is severely hindered by his obsession with loyalty. He rejects the advice of experienced institutional leaders – whether epidemiologists, diplomats, or military – who show him no loyalty. They have to “fuse” with him. If they don’t, Trump marginalizes or fires them.

In Uproar and his other books, Pete consistently advocates for “self-differentiated leadership.” Such a leader is not a reactionary, stuck in survival mode. A differentiated leader – Ernest Shackleton, the captain of Endurance, is the consummate example – uses the neo-cortex brain region that distinguishes humans from the rest of the animal kingdom to reason, to think clearly, and to communicate effectively with others to overcome obstacles. Courageous, principled and calm leadership – coming out of the space created by differentiation – is the type of leadership most especially needed during times of uproar.

Peter Steinke leaves a legacy of superior writing on leadership. May we who lead – whether large institutions, small businesses, or families – do so with courage and humility, self-awareness and responsibility, and a clear-eyed commitment to the values inherent to our missions.

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

August 13, 2020

The Lore of American Exceptionalism

Jorge Castañeda’s new book, America Through Foreign Eyes (Oxford, 2020), invites readers to consider the lore of American Exceptionalism. What exactly is it? Does it still exist? And if so, can Americans yet claim it with a straight face while Donald Trump is president?

[image error]

The author of this 250-page book offers a layered perspective. A Mexican national who has spent decades living and working in the US (and in other parts of the world), Castañeda knows the nuances of American culture and language yet manages to maintain the detached viewpoint of an outsider. Only once did I notice him using first person plural – “we” – when talking about the country he knows so well north of the Rio Grande.

America’s exceptionalism, he writes, started with its economic creation of a middle class in the latter part of the nineteenth century. While Germany was the first country to offer a state-sponsored social safety net under Bismarck in the 1880s, America’s DNA was cast: a populous middle class de facto was in and of itself a social safety net. While most European nations’ class stratifications persisted, America made the argument that a country’s economic engine, and consequent social mobility, would provide the necessary benefits for its populace.

Of course, many Americans were excluded from the blessings inherent to the establishment of a middle class: Blacks, Latinos, Chinese immigrants, Native Americans. More on this type of exceptionalism below. The devastations of the Great Depression forced the US to institute social safety nets in the 1930s. America, as a society, has struggled ever since with the necessity of state-sponsored social programs. Castañeda reminds us that – another form of exceptionalism – the US is the only one of the thirty-five industrialized nations in the world today that doesn’t offer universal healthcare to its citizenry. Try to fight a pandemic without a national healthcare safety net.

Castañeda, however, sees that American Exceptionalism is a pendulum that swings both ways. The emergence of the world’s first middle-class society (again, restricted mostly to whites), produced an American “mass culture.” This mass culture was a form of social and economic egalitarianism enviable to the rest of the world. Products from automobiles and refrigerators to radios and televisions were not solely the providence of elites, but of all.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, most of the states in the union jumped on the compulsory public education bandwagon, while long-established European societies clung to idea that education was the mainstay of elites. The literacy rate of 88 percent for American whites in 1870 was comparably much higher than that of British, French, and German citizens. Additionally, the widespread proliferation of free public libraries was an American innovation. The US was the first country, Castañeda illustrates, to favor its middle classes and not just its elites. This was and is exceptional, in the best of ways.

But therein lies the rub.

The historic and deeply-engrained restrictions of Blacks and browns from this egalitarian favor is anathema to Castañeda. Continuing the above comparison, the literacy rate for Blacks in America in 1870 is estimated at 20 percent, rising to 70 percent by 1910. Castañeda references other foreign observers – 150 years’ worth – similarly calling out this society’s racism, describing it as “the greatest condemnation of the American experience . . . the most flagrant and hateful contradiction between the promise of the country at birth and its reality nearly two hundred and fifty years later.”

This is a horrific exceptionalism. Castañeda points out a reality I had not previously considered: While the British, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Belgians all enforced and exploited slavery, only the United States and Brazil – of today’s industrialized nations – did so on their own land. This odiousness, much more than a past blemish, actively plagues this land.

Latino and Asian immigrants, he writes, have had better success than Blacks at integrating into American society. Why? While these immigrants have suffered deep exclusions, neither group was institutionally enslaved. As one of many examples to illustrate racism’s long reach, he states that the intergenerational transfer of wealth – 2012 presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s “get a $20,000 loan from your parents” – is essentially non-existent for Black families in this country.

America, he writes, is exceptional because it allowed and promoted equality for many. Yet, America’s persistent and centuries-long exclusions towards Blacks and other minorities nullifies foundational American credos such as “all are created equal” and “liberty and justice for all.” Additionally, American economic inequality, currently on a forty-year run, is making America like the countries of yesterday’s Europe and like many other countries today where elites enjoy and cultivate favor at the expense of the lower and middle classes.

Castañeda also dives deep into explanations on America’s current political gridlock, arguing that our political system – its original participants a relatively small group of white landowners – is incompatible with today’s entrenched inequality and surging heterogeneity of the voting populace.

An admirer, participant in and benefactor of the American experiment, Castañeda bemoans the dulling of America’s exceptional shine. No longer favoring the middle class, America’s inequalities make her like so many other countries in the world. She will need, he writes, to forge ahead as the other industrialized countries have done by offering additional social safety nets. The coronavirus’s far-reaching effects upon America’s public health and economy – exacerbated by Trump’s inept and vacant leadership – have verified Castañeda’s views which received their final edits months before Trump claimed, in February, that the virus would simply “disappear.”

[image error]

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

[image error]

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”