T. Carlos Anderson's Blog, page 2

April 25, 2024

My Next Book – Fall 2024

There is a Balm in Huntsville came out, no foolin’, on April 1, 2019. A nonfiction narrative using present-tense voice, it tells the story of the development of the first state-sponsored victim-offender dialogue program in the nation. Within this story, one prisoner’s tale of transformation through this ground-breaking restorative justice practice is told. Readers and a number of reviewers agree—Balm is a page-turner that reveals the power of truth-telling.

More than five years later, I’m pleased to announce that a book in the same vein, There is a Balm in Wichita Falls: The Healing Journeys of Mr. White and the Ninja Lady, will be released later this year. Using the same nonfiction narrative style as its predecessor, Balm II (as I’m calling it) tells the separate stories of two crime-victim survivors who eventually meet and join together in the search for answers and healing.

Balm II is intended for church groups, book clubs, and persons interested in restoration and recovery. It will expose readers to the core concepts of restorative justice as it highlights the healing journeys of two extraordinary and unforgettable protagonists. It will be published by Wipf & Stock in the fall of 2024.

March 7, 2024

Bluebonnets – Life and Beauty in the Face of Adversity

What would you do if you won a beautiful handmade bluebonnet quilt? I was recently faced with such a question after winning the main prize of our church’s raffle fundraiser. A few fellow church members ribbed me for winning, as if a pastor was ineligible to win. Ha—I paid for my raffle tickets like everyone else and was happy to support our congregation’s food pantry, one destination for the funds.

As I explained in a subsequent sermon message, it was appropriate that I won since I’m known as the “bluebonnet guy” in our neighborhood. We have a semi-xeriscape yard and each spring it draws onlookers with its array of cobalt bluebonnets and crimson and pink poppies. Even the Davis Lane median behind our house boasts of bluebonnets because I’ve sown seeds there. In May and June when the bluebonnets in nearby South Austin public spaces seed out, I turn into Robin Hood and equitably distribute seeds to other nearby locales that need a burst of spring color.

Many Texans are unaware that bluebonnets start their growing cycle each fall as rains coax seeds from the previous season to sprout. The little plants can handle adversity—cold weather, even snow and ice, as they lay low from October to February. Ponder for a moment that most all of the Central Texas bluebonnet blooms we saw in 2021 came from plants that endured the week-long February freeze and snow cover. The bluebonnet is not only a cherished and beautiful plant, it’s a wise teacher of life’s ability to withstand and overcome adversity.

We need its teaching example, especially now. As if two years of the pandemic weren’t enough, a horrible and brutal invasion of a peaceful nation by its bullying neighbor has created gloom and anxiety for those of us following the news from afar.

In the third chapter of the book of Lamentations, the prophet Jeremiah writes about his people’s exile from their beloved Jerusalem as it fell to the invading Babylonian army. He chronicles the affliction he saw—people chained and crying for help, their teeth ground into the dirt and gravel, people forgetting what happiness and prosperity were. The invasion was brutal, hateful, and ugly.

It wasn’t, however, the end of the story. The prophet purposely recalled promises as a way to mitigate the destruction and misery that he and his people experienced. “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness . . . I will hope in him.”

For the prophet, remembering God’s past goodness and love was a way to help his people survive the onslaught of doubt, anxiety, and fear that adversity brought. Remembering God’s past goodness and love gave hope for tomorrow and the strength to act in the moment to counter adversity’s multiple effects.

Seeing bluebonnet blooms in the spring, I think, tells a similar story of life and beauty flourishing in the face of adversity. Again, this year, most of the bluebonnet blooms we currently see around Austin are from plants that survived a blanket of snow and ice in February.

My two-year-old granddaughter will be the recipient of the beautiful bluebonnet quilt, crafted by Diane McGowan of Abiding Love Lutheran Church. Diane is a retired AISD high school math teacher and co-founder of our church’s food pantry, a ministry that has provided nutrition and encouragement for individuals and families dealing with the adverse effects of living in poverty. This gift will give me the opportunity to teach my granddaughter, a young Central Texan, about the beautiful flowers she sees each spring in her grandparents’ yard and elsewhere. As she gets older and the quilt continues to keep her warm during the winter months, its beautiful images and patterns will remind her of spring’s promise—life, beauty, and vitality emerging on the heels of winter’s snow and ice.

Spring 2020 – Our South Austin front yard

Spring 2020 – Our South Austin front yardT. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

January 24, 2024

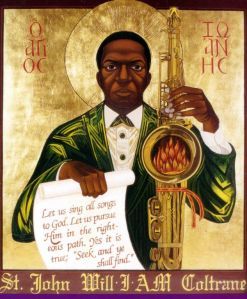

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

John Coltrane released his masterpiece A Love Supreme in February 1965. For those of you unfamiliar with Coltrane’s work, A Love Supreme is as fresh and timeless today as it was more than fifty years ago. Accessibly melodic, Coltrane’s exuberant tenor sax fuses with McCoy Tyner’s teeming piano chords and riffs to produce an unparalleled thirty-three-minute session of ascendant and flowing grace.

Give it a look and listen here:

Coltrane’s road to A Love Supreme was anything but straightforward. He was born in North Carolina in 1926. His father passed away when he was only twelve years old. Around this same time, a church music director introduced the young adolescent Coltrane to the saxophone. After moving to Philadelphia when he was seventeen, Coltrane enlisted in the US Navy and played clarinet in a military band while serving in Hawaii. He returned to Philadelphia in 1946 and dedicated himself to becoming a jazz musician.

He found success and played alongside the biggest names of the early bebop era: Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Johnny Hodges, and Miles Davis.

The hungry ghost of addiction haunted him; he was booted out of Miles Davis’s band in 1957 for continued heroin use, including a near overdose. The close call, however, propelled him to clean up. From the autobiographical liner notes of A Love Supreme: “During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life.” His calling was “to make others happy through music,” which, he claimed, was granted to him through God’s grace. “No matter what . . . it is with God. He is gracious and merciful. His way is in love, through which we all are. It is truly – A Love Supreme – .”

Yes, Coltrane’s credo – like some of his music later in his career – is a bit vague and esoteric. Let me put the credo in other terms, more accessible: love is a sufficiency all its own. In Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good, I detail the societal desire and drive that is never satisfied with enough, always seeking “just a little bit more.” Love is the antidote to the pursuit of more and more; it helps us to be grateful, to relax, to rest, to enjoy, to share, and to know what and when is enough. Love also helps us to do great things – busting our tails in the process – for our neighbor and the common good. Love covers it all.

John Coltrane died of liver cancer in 1967, having completed only 40 years of life on this earth. Forgive the obvious cliché – his music does live on. Coltrane biographer Lewis Porter (John Coltrane: His Life and Music, University of Michigan Press, 2000) explains that Coltrane plays the “Love Supreme” riff (four notes) exhaustively in all possible twelve keys toward the end of Part 1 – Acknowledgement, the first cut on the disc. Love as sufficiency – it covers all we need and then some.

The conclusion of Coltrane’s liner notes: “May we never forget that in the sunshine of our lives, through the storm and after the rain – it is all with God – in all ways and forever.”

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

December 30, 2023

Blessed Dryuary – Again

Eight years ago during Christmas, our daughter Alex shared her upcoming new-year endeavor : “Dryuary.” I had never heard the word before but understood it instantly – dry January. Alex, a vegetarian and daily exerciser, proceeded to converse with me and her mother, Denise, about the wisdom of bodily and mental detox after December’s season of excesses. It made an impression. A year later, Denise and I jumped on the Dryuary bandwagon and we thanked Alex for role-modeling the idea. Alex yet practices Dryuary as do other family members. This year will mark Denise’s and my seventh time to do Dryuary together.

As 2023 winds down, I especially look forward to Dryuary’s hiatus on alcohol. Denise and I have wine with most dinners . . . but purposely incorporating change into one’s habits gives an opportunity for perspective enhancement. Dryuary not only gives a mild cleanse to one’s psychological and physical states, but also a chance to reset them.

I’m in resetting mode and, to boot, there are good historical reasons that make the case for Dryuary and its invitation to reclaim the wisdom of moderation.

The winter solstice, December 21 – the shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere – has a deep cultural history related to the rhythms of year-end harvest. For millennia, the period preceding and following the solstice (what we moderns call October, November, December, and January) has been the time of gathering in harvests, slaughtering for fresh meat, and enjoying the products of fermentation, beer and wine. December was and is the time for excess – eating, drinking, celebrating, leisure – a time to enjoy labor’s rewards at year’s end.

Our modern-day December holiday season with gifts and the exaltation of consumerism, rich food and libations, and celebrations simply follows suit. Santa Claus, with his round belly and deep laugh, is the iconic representative of our modern season of excesses. (For those wondering about how December’s religious aspect – namely, the baby Jesus – fits into this topic, I cover that here.)

Have you ever put on a few pounds during the winter holidays? Have you ever signed up for a gym membership in January? If so, you’ve experienced the natural rhythms of this time of the year. There’s nothing wrong with occasional excesses. The hundreds of seeds produced by my garden’s basil and cilantro plants when they flower – in anticipation of next season’s reproduction – is a prime example of the goodness of excess.

When excess, however, becomes a way of life – addiction being excess’s most devious manifestation – problems multiply for individuals so afflicted and for the society in which they live. Eating, drinking, consumerism – all necessary parts of the human enterprise – are best done in moderation. This is the basic theme and message of my first book, Just a Little Bit More.

As we age, we slow down and our habits – both the good and bad ones – become more engrained. Youth’s ability to shrug off mistakes and pivot to new possibilities has diminished. Hopefully, for those of us in the aging mode, the wisdom of the years has accumulated and produced effective strategies for dealing with the vagaries of life. As we’ve heard it said: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven.”

I have, God willing, good plans for 2024: multiple house projects, weekly golf, publishing another book, and continuing the meaningful social ministry work I’m able to do with fantastic partners. Dryuary helps me get a head start on these good ambitions where needed.

Even though Twitter is awash with Dryuary bashing – “I made it 8 hours into this year’s #Dryuary before a bottle of reserve Rioja was calling my name . . . ” – I’m not persuaded otherwise. The pendulum has swung away from December into blessed Dryuary. I raise my glass of iced hibiscus tea with fresh mint to the new year!

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

December 11, 2023

Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown

I was almost four years old when the CBS network debuted A Charlie Brown Christmas on December 9, 1965. From the living room of a house that my parents rented on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota, I most likely watched its premiere. My dad was a second-year seminary student at the time, and, like many of his classmates, a big fan of Charles Schulz and his Peanuts comic strip. As my dad completed his education and began his career as a pastor and chaplain – prompting a family move to Portland, Oregon, a return to Minneapolis-St. Paul, and then a permanent relocation to the Chicago area – Christmas seasons for our family consistently centered upon snow, lights, a tree, presents, church, and plenty of anticipation. Watching A Charlie Brown Christmas, a show that incorporated all of these themes, was a high point of each Christmas celebration in my childhood home as our family grew to include my younger brothers and sister.

A generation later, my wife, Denise, and I lived in Houston with our three young children where I worked as a pastor. A cherished copy of A Charlie Brown Christmas was prominent in our VCR tape collection alongside copies of Disney classics that the kids watched over and again. As Christmas 1992 approached, it occurred to me that I needed more than the VCR copy of the Peanuts’ gang Christmas. I had to get a copy of the soundtrack. Those wondrous bits of jazz piano, bass and drums that undergirded the animated TV special beckoned me. I had heard its notes sway and its chords swing from my earliest days. There had to be a recording of these songs where the musicians stretched out.

These were pre-Amazon days. The CD era was cresting, but even so, it wasn’t until I went to a fourth or fifth “record store” (that’s what we called them back then) that I found a cooperative store manager who promised to order me (from an inventory catalog pulled down from a shelf) a CD of the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Bingo – Guaraldi and his bandmates stretched out magnificently, matching my expectations.

The next few Christmas seasons, I purchased additional copies of the CD and gifted them to family and friends. Then, in 1995, it was my turn to preach the Christmas Eve sermon at the church, Holy Cross Lutheran, I served in Houston. There was no question as to what I’d do for the message that year: a recapitulation of A Charlie Brown Christmas. It was a bit of a risk – telling a child’s tale for one of the largest worshipping crowds of the year. But I had the blessing of my pastoral colleague Gene Fogt and – even though the animation has no adult characters – I knew Charlie Brown’s story wasn’t just for kids.

The opening scene of the special features Charlie Brown confiding to his buddy Linus van Pelt: “I just don’t understand Christmas, I guess. I like getting presents . . . but I’m still not happy. I always end up feeling depressed.”

Writer Charles Schulz wonderfully develops a twenty-two minute animated homily from this starting confession to convey his own sense of Christmas’s true meaning: not the glitz and glitter of over-commercialization – which ultimately doesn’t deliver on its promise – but human and divine solidarity through the birth of a child. “For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger,” Linus tells Charlie Brown, quoting Luke 2.

A recently retired USAF colonel, Rolf Smith, was visiting the congregation that Christmas Eve with his family. He loved the sermon (as he told me later) and returned to Sunday worship services in the new year. As we got to know each other, I learned that Rolf had spearheaded the launch of “innovation” as a corporate strategy for the air force. To him, recasting A Charlie Brown Christmas for a sermon was “highly innovative.” That spring, he and his spouse, Julie, joined the church.

Another congregant, however, expressed her disdain to me about the sermon. She deemed a rendering of “a cartoon” as inappropriate for Christmas Eve worship. It wasn’t until a few years later that I discovered that a family member of hers struggled mightily with depression. The message was too close to home. For Christmas Eve worship, I surmised, she had not wanted any mention of depression and its effects.

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” Melendez

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” MelendezCharles Schulz, from his Sebastopol, California studio, collaborated with producer Lee Mendelson and animator Bill Melendez after Coca-Cola agreed to underwrite the special in the summer of 1965. Adhering to a fast-tracked schedule, Schulz and Melendez drew out 13,000 stills for the animation. Mendelson, having met and worked with the Grammy award-winning Guaraldi the previous year, commissioned the jazz pianist to record the soundtrack. A children’s choir from an Episcopal church sang for two of the tracks. Mendelson himself wrote the lyrics to Guaraldi’s tune Christmas Time is Here, now covered by hundreds of musicians the world over.

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince Guaraldi

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince GuaraldiA Charlie Brown Christmas is now playing its 59th Christmas season, and still going strong even for new generations.

When my son, Mitch, who was born in 1991, comes home to see us at Christmas, one of his first requests after hugging his mother is to hear some Christmas music – “the Snoopy and Charlie Brown disc.” I always oblige – he’s heard it every Christmas since he can remember. Lucky guy.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

November 8, 2023

Sharing More Than a Meal at Thanksgiving

Some years back my mother insisted that I watch the movie “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles.” Released in 1987, the movie revolves upon the difficulties of Thanksgiving holiday travel. On a deeper level, it’s also about the common grace that two very different individuals — Steve Martin’s uptight business executive and John Candy’s garrulous shower curtain ring salesman — find in each other. Appropriately, the paths of these two strangers, by suggestion of the movie’s final scene, will ultimately merge at a Thanksgiving table, where despite their differences, they will sit side by side.

Here’s the reason my mom recommended the movie: We had recently travelled on a family trip through Peru with all kinds of setbacks — flat tires, roadblocks and requests to prove our U.S. citizenship. The movie’s premise, however, seemed to me exceedingly cliché. But after a first viewing, I was hooked. Our family has watched the movie every Thanksgiving holiday since.

The first American Thanksgiving, legend tells us, brought Pilgrims and indigenous people together in peace in 1621 to share a bountiful harvest in present-day Massachusetts. Closer examination of the historical record reveals that the Pilgrims — half their numbers didn’t survive the previous winter — and the indigenous had plenty of reason to be wary of one another. The Pilgrims anticipated another brutal winter, and the Chief Massasoit-led Wampanoag were squeezed by their immigrant table guests to the east and their long-time rivals, the Narraganset, to the west. The first Thanksgiving, like the gathering featured in “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles,” was all about strangers encountering one another face to face, forced to consider the possibility that their differences did not outsize their commonalities.

American society is at a precarious state with the arrival of Thanksgiving 2019. Nationally, our politics have become divisive and hyper-partisan; in Texas, there are immigrant children separated from their parents and needlessly traumatized at the border; locally in Austin, there is a homelessness problem and statewide wrangling about how to respond to it. Longtime friends and family members sometimes don’t see eye-to-eye on these and other issues. Due to a crisis of national leadership, there is permission to disparage one another simply because of a difference of opinion.

This polarization threatens not only family gatherings, but civic life as well. Thanksgiving Day is the only national holiday with a specified menu, and consequently, the requirement to be seated at a table. At a table with turkey and varied trimmings, we encounter one another — family, friends and sometimes strangers — with a face-to-face intimacy that is not required on July 4 or Labor Day.

My wife and I lived with our infant daughter in Perú in the late 1980s as I completed a two-year internship during my seminary education. When my parents, who spoke zero Spanish, visited us, food and tables were exclusively the method by which they met Peruvians (few who spoke English). My wife and I were the translators — bridgers — to explain the food and personally connect those who shared the table.

In this hyper-partisan age, those of us who are bridgers have an abundance of worthy and necessary work to do. Gratitude, generosity, and grace are the classic Thanksgiving virtues shared at the table. After we turn the calendar on Thanksgiving, may we have the civic pride to continue to practice these virtues with family, neighbors, political adversaries and even strangers. Our very survival as a civil society depends upon it.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

October 26, 2023

Better Than Church

The women file past me into the room. They all wear the same bland prison whites, a pullover top matched to loose pants with an elastic waistband. Most of the women are in their twenties and thirties, and not attractive in the conventional sense. Their collective presence jars me, though I do my best to appear nonchalant. The prison unit, a substance abuse felony punishment facility in Texas that offers treatment for alcohol and drug abuse, claims them for seven to twelve months because of drug possession or DWI conviction. A number of the women are missing teeth, due to crystal meth abuse. Some of the women’s faces betray hard decisions and painful memories – of which I will hear when they begin to speak.

I’m at a graduation ceremony for Bridges To Life (BTL), a restorative justice prison ministry that joins surrogate crime victims and perpetrators face to face. (BTL is a volunteer program that is not part of the prison’s in-house drug treatment efforts, but it buttresses those efforts all the same.) All of the women in the room have completed the ministry’s fourteen-week program that coaxes forth self-awareness, accountability, and restoration by requiring participants to engage in rigorous self-evaluation. Small group discussions allow participants to honestly share their stories with one another. The traditional healing practices of confession and forgiveness are used to help inmates examine the effects of their crimes upon themselves, upon their relationships with family and friends, and upon the relationships their offenses have created with the victims of their crimes.

It’s open mic for this ceremony night of graduation. Three questions guide the women’s remarks: 1) How have you changed in the last fourteen weeks? 2) How do you feel now? 3) What do you want to say to the group?

The first woman to speak steps up to the wood podium in front of six neat rows of folding chairs, where her fellow inmates, ten BTL volunteers, the prison chaplain, and I watch her intently. She tries to speak but can’t as tears well up in her eyes. Immediately, a chorus of snapping fingers, raised in the air – as I’ll learn, their particular expression of support – fills the room. The woman covers her face with her hand and wipes her tears. She takes a deep breath and begins: “For the first time in a long time, I’m living actively and not passively. I feel alive again and my attitude has changed immensely. I’m letting feelings about my past go as I’ve learned I need to forgive myself. I feel important to myself again.” This last phrase jars me, but in a distinct manner from the jarring that internally shook me when the women filed into the room. I feel important to myself again – this particular description, the tip of an iceberg of human darkness and light, sets the stage. I will hear variations on the same potent theme for the next seventy-five, tear-inspiring minutes.

Released emotions, more tears, and at-the-ready snapping fingers accompany the ensuing testimonies, each one upon its conclusion met with cheers and applause that buoy the speaker back to her seat:

“I didn’t feel like I was worthy of change before, because I came here with a lot of guilt and shame . . . but now I have acceptance.”

“My everything has changed – the way I look at others and the way I look at myself. I’m proud of myself. I haven’t been proud of myself for years.”

“For so long, I hated myself and couldn’t forgive myself. But I feel lighter and freer now. The more I tell people about my weakness, the more restored God has made me feel. I have hope again.”

“Before I started this program, I felt like I was a victim. But when we wrote our letters, it occurred to me that I had harmed other people. I was blind, but now I see.”

The letters to which the speaker refers are confessional letters of apology to those harmed by the offender’s actions. A letter is written to a family member and a victim of the offender’s crime – the letters are not sent but used for small group discussion in one of the weekly BTL sessions, for the purpose of grabbing ahold of responsibility and accountability.

Others similarly testify:

“Some of us haven’t had positive role models in our lives. To have ears listening to us, helps restore my hope. I have a future again.”

“I never used to care about completing anything. Receiving this certificate tonight is so important – now I know I can complete things. My self-esteem has been lifted up so much.”

“To come here and be loved and accepted and forgiven – we’re all God’s little miracles.”

Toward the end of the testimonies, another woman, after fighting back tears like so many before her, shares with the group six words of profound self-understanding:

“Now I remember who I am . . .”

By this time, I’ve come upon an eye-opening realization myself. I see that what these women are sharing, straight from their souls, is the most beautiful thing I’ve witnessed in some time. As a male in the yet male-dominated twenty-first century world, my first glance at women often times, almost instinctively, is one of simple examination for what my eye understands to be beauty or good looks. I don’t say this in a braggadocious way, but in a truthful and confessional way. The women this night – some with missing teeth, and others unkempt in prison whites and freed from having to present themselves to the outside world – remind me that what binds us together more than anything is the common humanity we carry inside consisting of feelings, emotions, and experiences. All of us are in need of the inner gifts of love, acceptance, and support. Outward displays of possessions, accomplishments, and good looks – all of these having positive attributes – are overemphasized in popular culture, often to the detriment of the more important inner gifts.

The woman who invited me to the graduation, Ellen Halbert, told me ahead of time: “You’ll see. The graduation ceremony is incredible.” She was, and is, absolutely right. Ellen is a crime victim and a prominent restorative justice proponent – the prison unit in Burnet, Texas where we’ve gathered for the graduation, is named for her. She was a presenter, during an earlier session of the fourteen-week program with this same group. The women were so moved by hearing Ellen’s story of survival and empowerment that they insisted she come back for their graduation.

As we linger in the room and share refreshments with the graduates and volunteers, I – a preacher – share with Ellen my evaluation of the evening: “You’re right, Ellen. This was great – better than church.” She smiles and nods her head. She’s seen it before and she’ll see it again: the healing power of shared story and testimony to make a new way forward, for bearer and listener alike.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

Ellen Halbert and T. Carlos Anderson – 2019

Ellen Halbert and T. Carlos Anderson – 2019

June 27, 2023

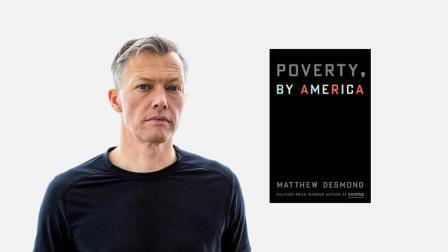

Poverty, By America – Book Review

Matthew Desmond’s new book, Poverty, By America, takes a hard look at prevalence of poverty in the richest country in the history of the world. As a writer on inequality and a pastor who works alongside low-income individuals and families, I enthusiastically recommend the book.

You might not agree with all of what Desmond writes about poverty in America—its causes, its persistence and proliferation, and his proposals for eradicating it. Not reading Desmond’s work, however, is akin to putting one’s head in the sand. His voice is one of the most prominent in the current debate on poverty in this country.

Desmond is a Princeton University sociologist and urban ethnographer. Although he previously taught at Harvard, he’s not a blue blood. At the turn of the century, he went to college with his parents’ encouragement but not their financial backing. While Desmond was in college, his working-class parents (his dad was a bi-vocational pastor) were not able to keep up with mortgage payments and a bank foreclosed on their home in Winslow, Arizona— the home in which Desmond grew up. It became a defining moment in his educational and vocational journey.

Desmond went on to graduate school in Madison at the University of Wisconsin. He figured studying sociology would give him the best chance to better understand, on a larger scale, the poverty his family knew personally. Ever since the Gilded Age helped make John D. Rockefeller the world’s first billionaire, the debate about poverty in America has been spirited. Left-leaners blame poverty on structural forces (discrimination, for example) and right-leaners focus on individual deficiencies.

Desmond argues for a comprehensive look at poverty that includes the voices of those living in it. “The poor were being left out of the inequality debate, as if we believed the livelihoods of the rich and the middle class were entwined but those of the poor and everyone else were not.”

The above quote comes from Desmond’s previous book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, which won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. As part of his research for Evicted, Desmond lived parts of two years in a trailer park and a low-income neighborhood in Milwaukee. This choice lent his research and subsequent writing a greater sense of validity and authority.

Desmond has critics—some of these pundits cashing paychecks from orgs and thinktanks on the far-right end of the political spectrum—who continue to sell the simplistic notion that poverty is primarily self-induced. The poor are lazy, hooked on government largesse, and/or are properly paying for their own foolish decisions and mistakes. Certainly, some living in poverty fit these categorical descriptions. But not all poor folks—especially the children living in poverty in this great nation—can be thus accused. Desmond notes that Germany, Canada, and South Korea have half the rate of children living in poverty than the US.

That the poor are solely responsible for their status is a convenient theory held by many, the aforementioned pundits included, who live in the well-to-do camp and, as a consequence, have zero interactions with those who are poor. As Desmond’s above quote alludes to, it’s best that those weighing in on the plight of the poor—especially pundits and politicians—actually have conversations and interactions with them.

Desmond leads the work of “Eviction Lab” at Princeton University. His team of researchers and students gather data on evictions throughout the country, with the mission of exposing the link between housing insecurity and poverty.

A crucial topic covered in Desmond’s new book, based on the research of Eviction Lab, is the symbiotic relationship between “private opulence and public squalor”—a reality alive and well in the US as much as it ever has been.

“As people accumulate more money, they become less dependent upon public goods and, in turn, less interested in supporting them. If they get their way, through tax breaks and other means, personal fortunes grow while public goods are allowed to deteriorate. As public housing, public education, and public transportation become poorer, they become increasingly, then almost exclusively, used only by the poor themselves” (pgs. 105–106).

The increasing income and economic segregations that exist in the US today, Desmond writes, is upheld by our political and personal choices. He calls the mortgage interest deduction a public housing policy benefit mostly for the rich; the stagnation of low wages he deems exploitation of the working poor; and, exclusionary zoning policies (i.e., prohibiting multi-family housing or smaller, affordable houses in high-income neighborhoods) he calls a polite and quiet way of promoting segregation.

Toward the end of the book, Desmond writes that “poverty abolition is a personal and political project” (p. 183). Austin City Lutherans’ ministry efforts—our food pantry, rent assistance programs, and furniture and household items provision for those transitioning from the streets to housing—will continue to be led by biblical mandates: “Love your neighbor,” “Bear one another’s burdens,” and “Care for orphans and widows in their distress.” As director of our ministries, I’ll make sure our organization is also paying attention to the words and works of Matthew Desmond, a prominent leader for positive change in the fight against the injustice of poverty.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

June 18, 2023

American-Made Mass Shootings – Again and Again

Remember the days when mass shootings in this country were rare events by rogue actors? Those days are long gone, as American-style mass gun violence—four or more people shot in a single incident—occurs daily.

The combination of readily available weapons and a society in crisis—politically polarized, beset by increasing inequality, exhausted by a pandemic—is making America less safe and more violent.

As religious leaders whose political views are shaped by theological convictions (and not the other way around), we say that it’s time to confront escalating gun violence with morality.

Jesus said not “fear” but to “love your neighbor.” His peacemaking advocacy was not based on the stockpiling weapons, but upon human-to-human, face-to-face relationships. Yes, some relationships are risky in this day and age. But foregoing them is becoming more and more deadly.

We don’t propose to have all the answers. We call upon people to talk with one another—in neighborhoods, at town halls and other public venues—to help shape how we should rightfully live together. And to consider the moral issues at play. We offer the following talking points.

The Second Amendment, historically, was to forge a power balance between citizens and a potentially over-reaching government. Extremists today stretch this understanding to “constitutional carry,” a dangerous interpretation championed by a gun lobby that profits (obscenely) from growing fears and chronic prejudices. It’s as if the political allies of the gun lobby are convinced that public safety is best carried out by crowdsourcing, even though many gun-toting “heroes” have never taken a gun-safety class or live-fire training.

Some fellow citizens warp the great American virtues of liberty and freedom to the point where these cherished ideals become excuses for irresponsible behavior. “I can do whatever I want”— cheat on taxes, vent and rage on an airplane or in other public spaces, and so on.

Violent assaults are on the rise. The “short-time-to-crime” window, where a weapon is purchased with the intent of committing a crime, has exploded. In 2020, the number of firearms purchased and then used in a crime within seven months more than doubled the 2019 rate.

When individual freedoms restrict and destroy communal freedoms, as they are now, it’s time for a social rebalancing, measuring the common good against an individual’s rights. Both need to be in play, but not submerging the other. This may even require amending the federal constitution.

This “anything I want” overindulgence spills over into allowing 18-year-old males to buy assault weapons. They can buy these modern-day killing machines and endless amounts of ammunition, but not cigarettes or alcohol. This, even though, the human neo-cortex, which regulates risk-taking behavior, isn’t fully developed until age 25. We call this “mature conscience,” and it should affect the age for gun purchases.

Politicians who take campaign donations from gun manufacturers and do nothing to change the purchase age of assault weapons—much less outlaw their sale entirely—are the leading enablers of mass killers. In our view, they are not acting like moral leaders.

The blood of innocent school children and their teachers, like those slaughtered in Uvalde and Santa Fe, Texas, is on the hands of politicians who do little to change the ever-worsening status quo.

The deterioration of community exacerbates this issue. We have innocent people knocking on the wrong door or driving their cars into the wrong driveway—only to be shot to death by fear-entrenched persons, cradling their smoking guns as they “protect” themselves and their property. Who is the criminal element in these appalling incidents?

Like most others, we have had enough. Mass shootings cannot become accepted as normal. Unless we make changes, we can expect them to happen again and again. What’s happened to American community values? Other countries have found the right moral balance between community safety and liberty, and have restricted mass gun violence.

Let’s work together to put a stop to “again.”

January 1, 2023

Blessed Dryuary – Again

Seven years ago during Christmas, our daughter Alex shared her upcoming new-year endeavor : “Dryuary.” I had never heard the word before but understood it instantly – dry January. Alex, a vegetarian and daily exerciser, proceeded to converse with me and her mother, Denise, about the wisdom of bodily and mental detox after December’s season of excesses. It made an impression. A year later, Denise and I jumped on the Dryuary bandwagon and we thanked Alex for role-modeling the idea. Alex yet practices Dryuary as do other family members. This year will mark Denise’s and my sixth time to do Dryuary together.

As 2022 wound down, I especially looked forward to Dryuary’s hiatus on alcohol. Denise and I have wine with most dinners . . . but with Covid-induced staying at home and fewer evening meetings on my schedule, I’ve consumed more wine with dinners – and afterwards – than in previous years. Dryuary not only gives a mild cleanse to one’s psychological and physical states, but also a chance to reset them.

I’m in resetting mode and, to boot, there are good historical reasons that make the case for Dryuary and its invitation to reclaim the wisdom of moderation.

The winter solstice, December 21 – the shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere – has a deep cultural history related to the rhythms of year-end harvest. For millennia, the period preceding and following the solstice (what we moderns call October, November, December, and January) has been the time of gathering in harvests, slaughtering for fresh meat, and enjoying the products of fermentation, beer and wine. December was and is the time for excess – eating, drinking, celebrating, leisure – a time to enjoy labor’s rewards at year’s end.

Our modern-day December holiday season with gifts and the exaltation of consumerism, rich food and libations, and celebrations simply follows suit. Santa Claus, with his round belly and deep laugh, is the iconic representative of our modern season of excesses. (For those wondering about how December’s religious aspect – namely, the baby Jesus – fits into this topic, I cover that here.)

Have you ever put on a few pounds during the winter holidays? Have you ever signed up for a gym membership in January? If so, you’ve experienced the natural rhythms of this time of the year. There’s nothing wrong with occasional excesses. The hundreds of seeds produced by my garden’s basil and cilantro plants when they flower – in anticipation of next season’s reproduction – is a prime example of the goodness of excess.

When excess, however, becomes a way of life – addiction being excess’s most devious manifestation – problems multiply for individuals so afflicted and for the society in which they live. Eating, drinking, consumerism – all necessary parts of the human enterprise – are best done in moderation. This is the basic theme and message of my first book, Just a Little Bit More.

As we age, we slow down and our habits – both the good and bad ones – become more engrained. Youth’s ability to shrug off mistakes and pivot to new possibilities has diminished. Hopefully, for those of us in the aging mode, the wisdom of the years has accumulated and produced effective strategies for dealing with the vagaries of life. As we’ve heard it said: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven.”

I have, God willing, good plans for 2023: multiple house projects, weekly golf, publishing another book, continuing the meaningful social ministry work I’m able to do with fantastic partners, and – along with everyone else – I look forward to post-pandemic recovery. Dryuary helps me get a head start on these good ambitions where needed.

Even though Twitter is awash with Dryuary bashing – “I made it 8 hours into this year’s #Dryuary before a bottle of reserve Rioja was calling my name . . . ” – I’m not persuaded otherwise. The pendulum has swung away from December into blessed Dryuary. I raise my glass of iced hibiscus tea with fresh mint to the new year!

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”