T. Carlos Anderson's Blog, page 3

December 8, 2022

Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown

I was almost four years old when the CBS network debuted A Charlie Brown Christmas on December 9, 1965. From the living room of a house that my parents rented on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota, I most likely watched its premiere. My dad was a second-year seminary student at the time, and, like many of his classmates, a big fan of Charles Schulz and his Peanuts comic strip. As my dad completed his education and began his career as a pastor and chaplain – prompting a family move to Portland, Oregon, a return to Minneapolis-St. Paul, and then a permanent relocation to the Chicago area – Christmas seasons for our family consistently centered upon snow, lights, a tree, presents, church, and plenty of anticipation. Watching A Charlie Brown Christmas, a show that incorporated all of these themes, was a high point of each Christmas celebration in my childhood home as our family grew to include my younger brothers and sister.

A generation later, my wife, Denise, and I lived in Houston with our three young children where I worked as a pastor. A cherished copy of A Charlie Brown Christmas was prominent in our VCR tape collection alongside copies of Disney classics that the kids watched over and again. As Christmas 1992 approached, it occurred to me that I needed more than the VCR copy of the Peanuts’ gang Christmas. I had to get a copy of the soundtrack. Those wondrous bits of jazz piano, bass and drums that undergirded the animated TV special beckoned me. I had heard its notes sway and its chords swing from my earliest days. There had to be a recording of these songs where the musicians stretched out.

These were pre-Amazon days. The CD era was cresting, but even so, it wasn’t until I went to a fourth or fifth “record store” (that’s what we called them back then) that I found a cooperative store manager who promised to order me (from an inventory catalog pulled down from a shelf) a CD of the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Bingo – Guaraldi and his bandmates stretched out magnificently, matching my expectations.

The next few Christmas seasons, I purchased additional copies of the CD and gifted them to family and friends. Then, in 1995, it was my turn to preach the Christmas Eve sermon at the church, Holy Cross Lutheran, I served in Houston. There was no question as to what I’d do for the message that year: a recapitulation of A Charlie Brown Christmas. It was a bit of a risk – telling a child’s tale for one of the largest worshipping crowds of the year. But I had the blessing of my pastoral colleague Gene Fogt and – even though the animation has no adult characters – I knew Charlie Brown’s story wasn’t just for kids.

The opening scene of the special features Charlie Brown confiding to his buddy Linus van Pelt: “I just don’t understand Christmas, I guess. I like getting presents . . . but I’m still not happy. I always end up feeling depressed.”

Writer Charles Schulz wonderfully develops a twenty-two minute animated homily from this starting confession to convey his own sense of Christmas’s true meaning: not the glitz and glitter of over-commercialization – which ultimately doesn’t deliver on its promise – but human and divine solidarity through the birth of a child. “For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger,” Linus tells Charlie Brown, quoting Luke 2.

A recently retired USAF colonel, Rolf Smith, was visiting the congregation that Christmas Eve with his family. He loved the sermon (as he told me later) and returned to Sunday worship services in the new year. As we got to know each other, I learned that Rolf had spearheaded the launch of “innovation” as a corporate strategy for the air force. To him, recasting A Charlie Brown Christmas for a sermon was “highly innovative.” That spring, he and his spouse, Julie, joined the church.

Another congregant, however, expressed her disdain to me about the sermon. She deemed a rendering of “a cartoon” as inappropriate for Christmas Eve worship. It wasn’t until a few years later that I discovered that a family member of hers struggled mightily with depression. The message was too close to home. For Christmas Eve worship, I surmised, she had not wanted any mention of depression and its effects.

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” Melendez

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” MelendezCharles Schulz, from his Sebastopol, California studio, collaborated with producer Lee Mendelson and animator Bill Melendez after Coca-Cola agreed to underwrite the special in the summer of 1965. Adhering to a fast-tracked schedule, Schulz and Melendez drew out 13,000 stills for the animation. Mendelson, having met and worked with the Grammy award-winning Guaraldi the previous year, commissioned the jazz pianist to record the soundtrack. A children’s choir from an Episcopal church sang for two of the tracks. Mendelson himself wrote the lyrics to Guaraldi’s tune Christmas Time is Here, now covered by hundreds of musicians the world over.

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince Guaraldi

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince GuaraldiA Charlie Brown Christmas is now playing its 58th Christmas season, and still going strong even for new generations.

When my son, Mitch, who was born in 1991, comes home to see us at Christmas, one of his first requests after hugging his mother is to hear some Christmas music – “the Snoopy and Charlie Brown disc.” I always oblige – he’s heard it every Christmas since he can remember. Lucky guy.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

May 26, 2022

Bluebonnets – Life and Beauty in the Face of Adversity

What would you do if you won a beautiful handmade bluebonnet quilt? I was recently faced with such a question after winning the main prize of our church’s raffle fundraiser. A few fellow church members ribbed me for winning, as if a pastor was ineligible to win. Ha—I paid for my raffle tickets like everyone else and was happy to support our congregation’s food pantry, one destination for the funds.

As I explained in a subsequent sermon message, it was appropriate that I won since I’m known as the “bluebonnet guy” in our neighborhood. We have a semi-xeriscape yard and each spring it draws onlookers with its array of cobalt bluebonnets and crimson and pink poppies. Even the Davis Lane median behind our house boasts of bluebonnets because I’ve sown seeds there. In May and June when the bluebonnets in nearby South Austin public spaces seed out, I turn into Robin Hood and equitably distribute seeds to other nearby locales that need a burst of spring color.

Many Texans are unaware that bluebonnets start their growing cycle each fall as rains coax seeds from the previous season to sprout. The little plants can handle adversity—cold weather, even snow and ice, as they lay low from October to February. Ponder for a moment that most all of the Central Texas bluebonnet blooms we saw in 2021 came from plants that endured the week-long February freeze and snow cover. The bluebonnet is not only a cherished and beautiful plant, it’s a wise teacher of life’s ability to withstand and overcome adversity.

We need its teaching example, especially now. As if two years of the pandemic weren’t enough, a horrible and brutal invasion of a peaceful nation by its bullying neighbor has created gloom and anxiety for those of us following the news from afar.

In the third chapter of the book of Lamentations, the prophet Jeremiah writes about his people’s exile from their beloved Jerusalem as it fell to the invading Babylonian army. He chronicles the affliction he saw—people chained and crying for help, their teeth ground into the dirt and gravel, people forgetting what happiness and prosperity were. The invasion was brutal, hateful, and ugly.

It wasn’t, however, the end of the story. The prophet purposely recalled promises as a way to mitigate the destruction and misery that he and his people experienced. “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness . . . I will hope in him.”

For the prophet, remembering God’s past goodness and love was a way to help his people survive the onslaught of doubt, anxiety, and fear that adversity brought. Remembering God’s past goodness and love gave hope for tomorrow and the strength to act in the moment to counter adversity’s multiple effects.

Seeing bluebonnet blooms in the spring, I think, tells a similar story of life and beauty flourishing in the face of adversity. Again, this year, most of the bluebonnet blooms we currently see around Austin are from plants that survived a blanket of snow and ice in February.

My two-year-old granddaughter will be the recipient of the beautiful bluebonnet quilt, crafted by Diane McGowan of Abiding Love Lutheran Church. Diane is a retired AISD high school math teacher and co-founder of our church’s food pantry, a ministry that has provided nutrition and encouragement for individuals and families dealing with the adverse effects of living in poverty. This gift will give me the opportunity to teach my granddaughter, a young Central Texan, about the beautiful flowers she sees each spring in her grandparents’ yard and elsewhere. As she gets older and the quilt continues to keep her warm during the winter months, its beautiful images and patterns will remind her of spring’s promise—life, beauty, and vitality emerging on the heels of winter’s snow and ice.

Spring 2020 – Our South Austin front yard

Spring 2020 – Our South Austin front yardT. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

April 3, 2022

What I Learned from César Chávez; Reflections on His Holiday

One of the highlights of my long legal career was the honor of serving as César Chávez’ lawyer for 18 years and for the United Farm Workers, AFL-CIO here in Texas during its organizing campaigns. I also had the opportunity of marching with César on twin 60-mile marches in South Texas, from Brownsville and Rio Grande City that met in San Juan, to raise farm labor wages.

At this time of the year, when we commemorate César’s life with a holiday in many parts of the country, I always feel compelled to write a bit about his life and impact. I’ve done so for about 25 years now. This year, I want to focus on what I learned personally from him in the hope my reflections might be helpful for others involved in social change efforts.

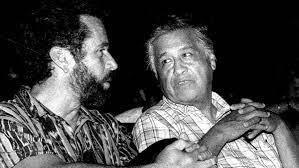

Jim Harrington and César Chávez, circa 1991

Jim Harrington and César Chávez, circa 1991César inspired many and changed their lives. He inspired me to move from Michigan to the Rio Grande Valley and work there. I learned much from him about the movement and how to be a lawyer that works with the community.

So, here my takeaways for your consideration, as they occur to me.

Love your family, and love everyone else and everyone else’s family.

Practice nonviolence as a way of life, not a movement tactic. Non-violence does not accept non-action, and may require fierce action. Farm workers were brutally beaten by police and goons during organizing campaigns, and three were killed. As John Lewis put it, you must look the person in the eye who is brutalizing you with the compassion of non-violence that understands your assailant is as much of a victim as the person being beaten. Love the person who is the brutalizer, but struggle against the system the brutalizer represents.

Keep focused on the goal and do not get distracted. There was once an impetus in the Chicano movement, as it was called then, to recognize César as its paramount national leader. He declined, saying his work was for the farm labor movement, and to that end, he would remain exclusively dedicated.

Develop a deep spirituality with the faith that justice will prevail no matter how ferocious, ruthless or sophisticated the opposing tactics are against the movement.

César never got beyond 8th grade because he had to join the migrant stream to help support his family, but that never stopped him from reading all the time. He always traveled with books of all kinds, and often read after everyone went to bed. Read, read, read.

Be personally disciplined, part of which is fasting. César, of course had three major weekslong fasts, one being to keep the movement in a mode of non-violence. He never suggested that others do that; but he was clear that weekly, regular fasting for a day or two was important.

Don’t be materialistic. Like other UFW organizers at the time, César earned $5/week, plus modest living expenses. Seeking a high salary, living in a nice part of town, driving an elegant car, for example, lead to distraction and self-centeredness.

As far as any form of a movement for justice (civil rights, economic, environmental), dignity is what’s at stake. From that, all justice flows.

We must live and breathe our cause; it is not a 40 hour/week endeavor. And we must work with the community and not just for it. As César often said, “If the poor are not involved, change will never come.” We don’t organize for, but with.

César may not be among us any longer, but his spirit is. He gave us an example of an unrelenting fierceness for justice, bringing together our common suffering and love for each other.

He framed it once this way: “The truest act of valor is to devote ourselves to others in the non-violent struggle for justice.”

Jim Harrington

Jim HarringtonHighly recommended Jim Harrington autobiographical article linked here.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

March 20, 2022

Bluebonnets – Life and Beauty in the Face of Adversity

What would you do if you won a beautiful handmade bluebonnet quilt? I was recently faced with such a question after winning the main prize of our church’s raffle fundraiser. A few fellow church members ribbed me for winning, as if a pastor was ineligible to win. Ha—I paid for my raffle tickets like everyone else and was happy to support our congregation’s food pantry, one destination for the funds.

As I explained in a subsequent sermon message, it was appropriate that I won since I’m known as the “bluebonnet guy” in our neighborhood. We have a semi-xeriscape yard and each spring it draws onlookers with its array of cobalt bluebonnets and crimson and pink poppies. Even the Davis Lane median behind our house boasts of bluebonnets because I’ve sown seeds there. In May and June when the bluebonnets in nearby South Austin public spaces seed out, I turn into Robin Hood and equitably distribute seeds to other nearby locales that need a burst of spring color.

Many Texans are unaware that bluebonnets start their growing cycle each fall as rains coax seeds from the previous season to sprout. The little plants can handle adversity—cold weather, even snow and ice, as they lay low from October to February. Ponder for a moment that most all of the Central Texas bluebonnet blooms we saw in 2021 came from plants that endured the week-long February freeze and snow cover. The bluebonnet is not only a cherished and beautiful plant, it’s a wise teacher of life’s ability to withstand and overcome adversity.

We need its teaching example, especially now. As if two years of the pandemic weren’t enough, a horrible and brutal invasion of a peaceful nation by its bullying neighbor has created gloom and anxiety for those of us following the news from afar.

In the third chapter of the book of Lamentations, the prophet Jeremiah writes about his people’s exile from their beloved Jerusalem as it fell to the invading Babylonian army. He chronicles the affliction he saw—people chained and crying for help, their teeth ground into the dirt and gravel, people forgetting what happiness and prosperity were. The invasion was brutal, hateful, and ugly.

It wasn’t, however, the end of the story. The prophet purposely recalled promises as a way to mitigate the destruction and misery that he and his people experienced. “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness . . . I will hope in him.”

For the prophet, remembering God’s past goodness and love was a way to help his people survive the onslaught of doubt, anxiety, and fear that adversity brought. Remembering God’s past goodness and love gave hope for tomorrow and the strength to act in the moment to counter adversity’s multiple effects.

Seeing bluebonnet blooms in the spring, I think, tells a similar story of life and beauty flourishing in the face of adversity. Again, this year, most of the bluebonnet blooms we currently see around Austin are from plants that survived a blanket of snow and ice in February.

My two-year-old granddaughter will be the recipient of the beautiful bluebonnet quilt, crafted by Diane McGowan of Abiding Love Lutheran Church. Diane is a retired AISD high school math teacher and co-founder of our church’s food pantry, a ministry that has provided nutrition and encouragement for individuals and families dealing with the adverse effects of living in poverty. This gift will give me the opportunity to teach my granddaughter, a young Central Texan, about the beautiful flowers she sees each spring in her grandparents’ yard and elsewhere. As she gets older and the quilt continues to keep her warm during the winter months, its beautiful images and patterns will remind her of spring’s promise—life, beauty, and vitality emerging on the heels of winter’s snow and ice.

Spring 2020 – Our South Austin front yard

Spring 2020 – Our South Austin front yardT. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

February 5, 2022

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

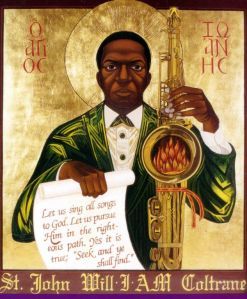

John Coltrane released his masterpiece A Love Supreme in February 1965. For those of you unfamiliar with Coltrane’s work, A Love Supreme is as fresh and timeless today as it was more than fifty years ago. Accessibly melodic, Coltrane’s exuberant tenor sax fuses with McCoy Tyner’s teeming piano chords and riffs to produce an unparalleled thirty-three-minute session of ascendant and flowing grace.

Give it a look and listen here:

Coltrane’s road to A Love Supreme was anything but straightforward. He was born in North Carolina in 1926. His father passed away when he was only twelve years old. Around this same time, a church music director introduced the young adolescent Coltrane to the saxophone. After moving to Philadelphia when he was seventeen, Coltrane enlisted in the US Navy and played clarinet in a military band while serving in Hawaii. He returned to Philadelphia in 1946 and dedicated himself to becoming a jazz musician.

He found success and played alongside the biggest names of the early bebop era: Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Johnny Hodges, and Miles Davis.

The hungry ghost of addiction haunted him; he was booted out of Miles Davis’s band in 1957 for continued heroin use, including a near overdose. The close call, however, propelled him to clean up. From the autobiographical liner notes of A Love Supreme: “During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life.” His calling was “to make others happy through music,” which, he claimed, was granted to him through God’s grace. “No matter what . . . it is with God. He is gracious and merciful. His way is in love, through which we all are. It is truly – A Love Supreme – .”

Yes, Coltrane’s credo – like some of his music later in his career – is a bit vague and esoteric. Let me put the credo in other terms, more accessible: love is a sufficiency all its own. In Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good, I detail the societal desire and drive that is never satisfied with enough, always seeking “just a little bit more.” Love is the antidote to the pursuit of more and more; it helps us to be grateful, to relax, to rest, to enjoy, to share, and to know what and when is enough. Love also helps us to do great things – busting our tails in the process – for our neighbor and the common good. Love covers it all.

John Coltrane died of liver cancer in 1967, having completed only 40 years of life on this earth. Forgive the obvious cliché – his music does live on. Coltrane biographer Lewis Porter (John Coltrane: His Life and Music, University of Michigan Press, 2000) explains that Coltrane plays the “Love Supreme” riff (four notes) exhaustively in all possible twelve keys toward the end of Part 1 – Acknowledgement, the first cut on the disc. Love as sufficiency – it covers all we need and then some.

The conclusion of Coltrane’s liner notes: “May we never forget that in the sunshine of our lives, through the storm and after the rain – it is all with God – in all ways and forever.”

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Community Development for Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

January 2, 2022

Blessed Dryuary – Again

Six years ago during Christmas, our daughter Alex shared her upcoming new-year endeavor : “Dryuary.” I had never heard the word before but understood it instantly – dry January. Alex, a vegetarian and daily exerciser, proceeded to converse with me and her mother, Denise, about the wisdom of bodily and mental detox after December’s season of excesses. It made an impression. A year later, Denise and I jumped on the Dryuary bandwagon and we thanked Alex for role-modeling the idea. Alex yet practices Dryuary as do other family members. This year will mark Denise’s and my fifth year to do Dryuary together.

As 2021 wound down, I especially looked forward to Dryuary’s hiatus on alcohol. Denise and I have wine with most dinners . . . but with Covid-induced staying at home and fewer evening meetings on my schedule, I’ve consumed more wine with dinners – and afterwards – than in previous years. Dryuary not only gives a mild cleanse to one’s psychological and physical states, but also a chance to reset them.

I’m in resetting mode and, to boot, there are good historical reasons that make the case for Dryuary and its invitation to reclaim the wisdom of moderation.

The winter solstice, December 21 – the shortest day in the Northern Hemisphere – has a deep cultural history related to the rhythms of year-end harvest. For millennia, the period preceding and following the solstice (what we moderns call October, November, December, and January) has been the time of gathering in harvests, slaughtering for fresh meat, and enjoying the products of fermentation, beer and wine. December was and is the time for excess – eating, drinking, celebrating, leisure – a time to enjoy labor’s rewards at year’s end.

Our modern-day December holiday season with gifts and the exaltation of consumerism, rich food and libations, and celebrations simply follows suit. Santa Claus, with his round belly and deep laugh, is the iconic representative of our modern season of excesses. (For those wondering about how December’s religious aspect – namely, the baby Jesus – fits into this topic, I cover that here.)

Have you ever put on a few pounds during the winter holidays? Have you ever signed up for a gym membership in January? If so, you’ve experienced the natural rhythms of this time of the year. There’s nothing wrong with occasional excesses. The hundreds of seeds produced by my garden’s basil and cilantro plants when they flower – in anticipation of next season’s reproduction – is a prime example of the goodness of excess.

When excess, however, becomes a way of life – addiction being excess’s most devious manifestation – problems multiply for individuals so afflicted and for the society in which they live. Eating, drinking, consumerism – all necessary parts of the human enterprise – are best done in moderation. This is the basic theme and message of my first book, Just a Little Bit More.

As we age, we slow down and our habits – both the good and bad ones – become more engrained. Youth’s ability to shrug off mistakes and pivot to new possibilities has diminished. Hopefully, for those of us in the aging mode, the wisdom of the years has accumulated and produced effective strategies for dealing with the vagaries of life. As we’ve heard it said: “For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven.”

I have, God willing, good plans for 2022: multiple house projects, recovering my golf game, writing another book, continuing the meaningful social ministry work I’m able to do with fantastic partners, and – along with everyone else – I look forward to the end of the pandemic. Dryuary helps me get a head start on these good ambitions where needed.

Even though Twitter is awash with Dryuary bashing – “I made it 8 hours into this year’s #Dryuary before a bottle of reserve Rioja was calling my name . . . ” – I’m not persuaded otherwise. The pendulum has swung away from December into blessed Dryuary. I raise my glass of iced hibiscus tea with fresh mint to the new year!

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

December 21, 2021

Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown

I was almost four years old when the CBS network debuted A Charlie Brown Christmas on December 9, 1965. From the living room of a house that my parents rented on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, Minnesota, I most likely watched its premiere. My dad was a second-year seminary student at the time, and, like many of his classmates, a big fan of Charles Schulz and his Peanuts comic strip. As my dad completed his education and began his career as a pastor and chaplain – prompting a family move to Portland, Oregon, a return to Minneapolis-St. Paul, and then a permanent relocation to the Chicago area – Christmas seasons for our family consistently centered upon snow, lights, a tree, presents, church, and plenty of anticipation. Watching A Charlie Brown Christmas, a show that incorporated all of these themes, was a high point of each Christmas celebration in my childhood home as our family grew to include my younger brothers and sister.

A generation later, my wife, Denise, and I lived in Houston with our three young children where I worked as a pastor. A cherished copy of A Charlie Brown Christmas was prominent in our VCR tape collection alongside copies of Disney classics that the kids watched over and again. As Christmas 1992 approached, it occurred to me that I needed more than the VCR copy of the Peanuts’ gang Christmas. I had to get a copy of the soundtrack. Those wondrous bits of jazz piano, bass and drums that undergirded the animated TV special beckoned me. I had heard its notes sway and its chords swing from my earliest days. There had to be a recording of these songs where the musicians stretched out.

These were pre-Amazon days. The CD era was cresting, but even so, it wasn’t until I went to a fourth or fifth “record store” (that’s what we called them back then) that I found a cooperative store manager who promised to order me (from an inventory catalog pulled down from a shelf) a CD of the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s A Charlie Brown Christmas.

Bingo – Guaraldi and his bandmates stretched out magnificently, matching my expectations.

The next few Christmas seasons, I purchased additional copies of the CD and gifted them to family and friends. Then, in 1995, it was my turn to preach the Christmas Eve sermon at the church, Holy Cross Lutheran, I served in Houston. There was no question as to what I’d do for the message that year: a recapitulation of A Charlie Brown Christmas. It was a bit of a risk – telling a child’s tale for one of the largest worshipping crowds of the year. But I had the blessing of my pastoral colleague Gene Fogt and – even though the animation has no adult characters – I knew Charlie Brown’s story wasn’t just for kids.

The opening scene of the special features Charlie Brown confiding to his buddy Linus van Pelt: “I just don’t understand Christmas, I guess. I like getting presents . . . but I’m still not happy. I always end up feeling depressed.”

Writer Charles Schulz wonderfully develops a twenty-two minute animated homily from this starting confession to convey his own sense of Christmas’s true meaning: not the glitz and glitter of over-commercialization – which ultimately doesn’t deliver on its promise – but human and divine solidarity through the birth of a child. “For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord. And this shall be a sign unto you; ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger,” Linus tells Charlie Brown, quoting Luke 2.

A recently retired USAF colonel, Rolf Smith, was visiting the congregation that Christmas Eve with his family. He loved the sermon (as he told me later) and returned to Sunday worship services in the new year. As we got to know each other, I learned that Rolf had spearheaded the launch of “innovation” as a corporate strategy for the air force. To him, recasting A Charlie Brown Christmas for a sermon was “highly innovative.” That spring, he and his spouse, Julie, joined the church.

Another congregant, however, expressed her disdain to me about the sermon. She deemed a rendering of “a cartoon” as inappropriate for Christmas Eve worship. It wasn’t until a few years later that I discovered that a family member of hers struggled mightily with depression. The message was too close to home. For Christmas Eve worship, I surmised, she had not wanted any mention of depression and its effects.

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” Melendez

Producer Lee Mendelson, Peanuts’ creator Charles Schulz, and animator José Cuahtomec “Bill” MelendezCharles Schulz, from his Sebastopol, California studio, collaborated with producer Lee Mendelson and animator Bill Melendez after Coca-Cola agreed to underwrite the special in the summer of 1965. Adhering to a fast-tracked schedule, Schulz and Melendez drew out 13,000 stills for the animation. Mendelson, having met and worked with the Grammy award-winning Guaraldi the previous year, commissioned the jazz pianist to record the soundtrack. A children’s choir from an Episcopal church sang for two of the tracks. Mendelson himself wrote the lyrics to Guaraldi’s tune Christmas Time is Here, now covered by hundreds of musicians the world over.

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince Guaraldi

Peanuts’ piano players: Schroeder and Vince GuaraldiA Charlie Brown Christmas is now playing its 56th Christmas season, and still going strong even for new generations.

When my son, Mitch, who was born in 1991, comes home to see us at Christmas, one of his first requests after hugging his mother is to hear some Christmas music – “the Snoopy and Charlie Brown disc.” I always oblige – he’s heard it every Christmas since he can remember. Lucky guy.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

November 23, 2021

Sharing More Than a Meal at Thanksgiving

Some years back my mother insisted that I watch the movie “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles.” Released in 1987, the movie revolves upon the difficulties of Thanksgiving holiday travel. On a deeper level, it’s also about the common grace that two very different individuals — Steve Martin’s uptight business executive and John Candy’s garrulous shower curtain ring salesman — find in each other. Appropriately, the paths of these two strangers, by suggestion of the movie’s final scene, will ultimately merge at a Thanksgiving table, where despite their differences, they will sit side by side.

Here’s the reason my mom recommended the movie: We had recently travelled on a family trip through Peru with all kinds of setbacks — flat tires, roadblocks and requests to prove our U.S. citizenship. The movie’s premise, however, seemed to me exceedingly cliché. But after a first viewing, I was hooked. Our family has watched the movie every Thanksgiving holiday since.

The first American Thanksgiving, legend tells us, brought Pilgrims and indigenous people together in peace in 1621 to share a bountiful harvest in present-day Massachusetts. Closer examination of the historical record reveals that the Pilgrims — half their numbers didn’t survive the previous winter — and the indigenous had plenty of reason to be wary of one another. The Pilgrims anticipated another brutal winter, and the Chief Massasoit-led Wampanoag were squeezed by their immigrant table guests to the east and their long-time rivals, the Narraganset, to the west. The first Thanksgiving, like the gathering featured in “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles,” was all about strangers encountering one another face to face, forced to consider the possibility that their differences did not outsize their commonalities.

American society is at a precarious state with the arrival of Thanksgiving 2019. Nationally, our politics have become divisive and hyper-partisan; in Texas, there are immigrant children separated from their parents and needlessly traumatized at the border; locally in Austin, there is a homelessness problem and statewide wrangling about how to respond to it. Longtime friends and family members sometimes don’t see eye-to-eye on these and other issues. Due to a crisis of national leadership, there is permission to disparage one another simply because of a difference of opinion.

This polarization threatens not only family gatherings, but civic life as well. Thanksgiving Day is the only national holiday with a specified menu, and consequently, the requirement to be seated at a table. At a table with turkey and varied trimmings, we encounter one another — family, friends and sometimes strangers — with a face-to-face intimacy that is not required on July 4 or Labor Day.

My wife and I lived with our infant daughter in Perú in the late 1980s as I completed a two-year internship during my seminary education. When my parents, who spoke zero Spanish, visited us, food and tables were exclusively the method by which they met Peruvians (few who spoke English). My wife and I were the translators — bridgers — to explain the food and personally connect those who shared the table.

In this hyper-partisan age, those of us who are bridgers have an abundance of worthy and necessary work to do. Gratitude, generosity, and grace are the classic Thanksgiving virtues shared at the table. After we turn the calendar on Thanksgiving, may we have the civic pride to continue to practice these virtues with family, neighbors, political adversaries and even strangers. Our very survival as a civil society depends upon it.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

October 19, 2021

The Code Breaker – Book Review

When I heard that biographer extraordinaire Walter Isaacson had written a new book focused on Messenger RNA (mRNA) and the race to produce a vaccine against Covid-19, I purchased The Code Breaker and bumped it up on my “to-read” list – a rare occurrence. Even though the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are the first genetic vaccines produced using mRNA technology, they act like other vaccines to spur the body to produce specific antibodies. The Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses the older technology – harkening back to Edward Jenner’s eighteenth-century discovery of using the cowpox virus to inoculate his patients against deadly smallpox – introducing an inactivated version of the coronavirus to spur immunity. Isaacson forwards the claim of the dozens of scientists he writes about in this book that mRNA vaccines in the future will be used to help humans fight off an array of genetic diseases, from Alzheimer’s to certain types of cancers.

The book primarily follows the career path of American code-breaking biochemist Jennifer Doudna, who, along with French scientist Emmanuelle Charpentier, won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work together to create a CRISPR-based gene-editing tool.

CRISPR is the acronym for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” and its technology is described by Isaacson as “based on a virus-fighting trick used by bacteria, which have been battling viruses for more than a billion years. In their DNA, bacteria develop clustered repeated sequences, known as CRISPRs, that can remember and then destroy viruses that attack them.” A CRISPR-editing tool, as instructed by mRNA, cuts up – as if a pair of scissors – targeted and unwanted genes in a strand of DNA.

Doudna and Charpentier are the sixth and seventh women to have won the Nobel for Chemistry of 184 total winners. Additionally, CRISPR-technique technology is employed to create mRNA vaccines. Messenger RNA instruct cells to produce Covid’s crowned “spike” protein, thus priming the recipient’s immune system to respond rapidly if the real coronavirus strikes. The injected mRNA dissolves after giving its instructions with no permanent (or even temporary) altering of DNA.

Scientists have known about the possibility of creating mRNA-based genetic vaccines since the late 1980s. But it wasn’t until 2012, when Doudna and Charpentier developed their CRISPR technology, that the door opened to the new era of genetic vaccines, giving humanity brand-new weapons in its survival-of-the-fittest campaign.

CRISPR has the potential to do all sorts of gene editing, from eliminating debilitating diseases like sickle cell and Huntington’s to enhancing human embryos with desired traits, such as eye, hair, and skin color, muscular build and height. Isaacson quotes Russian President Vladimir Putin touting the potential of CRISPR for human enhancements from a 2017 youth festival speech: “This may be a mathematical genius, an outstanding musician, but this can also be a soldier, a person who can fight without fear or compassion, mercy or pain.”

The ethical implications of CRISPR run deep.

Genetic control: Is it a new eugenics – a type of selective breeding to create higher quality humans? Could we eradicate not only sickle cell, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases, but also breast and ovarian cancers related to the BRCA gene? Would it be ethical NOT to eradicate certain genetic diseases? Will Putin (or his clone) one day have his heartless and robotic soldiers? Will the rich order designer babies? Who decides? Inequality is a huge issue in today’s world made up of humans produced by the genetic lottery. Severe inequality could become DNA-ingrained if a select percentage of the human race had access to the “genetic supermarket.”

The Code Breaker trumpets the optimism inherent to scientific discovery and advancement. Isaacson wisely tempers the enthusiasm however with the reality that we humans, with our new capabilities, might mess things up like never before.

Isaacson quotes Francis Collins, the outgoing director of the National Institute of Health: “Evolution has been optimizing the human genome for 3.85 billion years. Do we really think that some small group of genetic tinkerers could do better without all sorts of unintended consequences?”

Collins’s statement testifies to the fact that our scientific knowledge is yet lacking as concerns CRISPR gene editing. Doudna states that it should only be used when “medically necessary.” Isaacson quotes Doudna summarizing her thoughts based on the numerous ethics conferences on CRISPR she’s participated in: “Science doesn’t move backwards, and we can’t unlearn this knowledge, so we need to find a prudent path forward . . . We now have the power to control our genetic future, which is awesome and terrifying. So we must move forward cautiously and with respect for the power we’ve gained.”

The Code Breaker covers a lot of ground – scientific breakthroughs and the personalities driving them, Covid myths and realities, biomedical ethics – in its 500 pages. Highly recommended reading.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”

May 2, 2021

The Second Chance Club – Book Review

Author Jason Hardy worked as a probation and parole officer in New Orleans in the middle part of the previous decade. The Second Chance Club: Hardship and Hope after Prison (Simon & Schuster, 2020) details his interactions with a handful of his charges. Most everybody deserves a second chance, don’t they?

Hardy and his overworked fellow officers, each responsible for more than 200 cases, checked in with their “max risk” cases by visiting them at their places of residence. Some of these slept on family members’ couches, other tented under bridges at homeless camps, some resided at halfway houses, and others – drug dealers – lived in decked-out apartments in poor neighborhoods and drove Range Rovers.

For fresh parolees, Hardy writes that drug dealing and gang membership – much more so than slapping mayo on a customer’s footlong at Subway – “offer immediate relief from poverty, loneliness, and harassment” in those places like New Orleans East or the Lower Ninth Ward “where other opportunities for upward mobility are scarce” (p. 65, paperback).

Hardy, in his debut book, tells it like it is.

The book is not a hopeful read as it goes deep on the bleak realities faced by those re-entering society from prison. It is, however, a must read for those interested and those conversant in the criminal justice reform debate in the US, the home of the brave and of the mass-incarcerated. For twenty years, the US has had the world’s highest incarceration rate. We have only 5 percent of the world’s population but more than 20 percent of those incarcerated worldwide.

Prison boards, wardens, and guards have a dual mission: protection of society by separating inmates from civilians, and rehabilitation of inmates. (Critics and some supporters of the status quo assign a third purpose to the overall mission – punishment.)

Parole and probation officers are tasked with the same mission by seeing that their charges, still in the correctional system, follow the stipulations of their tenuous freedom.

Rehabilitation? Jason Hardy writes that the goal of his public service job is rather best described as “disaster prevention.” Criminal re-offense and drug overdose are the two prevalent disasters that Hardy and his co-worker officers most worried about.

Hardy, who grew up white and privileged in the New Orleans suburbs, followed in his parents footsteps and taught high school English right out of college. That lasted three years. In another three years, he had earned a Master’s degree in creative writing from LSU and produced a 300-page novel. He claims, however, that the novel was of such quality that even his mother didn’t like it. It didn’t get published.

“The Probation and Parole position,” he writes, “seemed like the best chance to make myself useful before I turned thirty.”

Hardy did his homework and knew the numbers going in. In the early ’70s, some 250,000 were incarcerated in the US. Today, that number has exploded to more than 2.2 million, with Blacks and Browns disproportionally represented. And of these 2 million plus, 90 percent will one day leave prison.

Which brings us back to rehabilitation and second chances. If only it was a simple as holding down that minimum-wage job at Subway and then working oneself up the ladder. Reading Hardy’s book is a reality check against such simplistic thinking.

Many states restrict voting rights for ex-prisoners, along with deeming them ineligible to receive SNAP (food stamps) and other benefits. Sometimes job applications ask, “Have you ever been convicted of a crime?” or “Have you ever been treated for drug addiction?”

Good rehabilitation programs for prisoners and parolees are far and few between. People who work and volunteer for restorative justice programs like the Texas prison system’s “Victim-Offender Dialog” and prison ministries like Bridges To Life – which I’ve written about – truly understand how the “90 percent issue” makes prisoner re-entry a vital social concern.

At the end of the book, Hardy advocates for two things. The first is prison re-entry programming tied to job-training. “Good jobs will always be the single strongest crime reduction measure there is” (p. 241).

The second is restorative justice practices. Hardy admits that he initially he “rolled his eyes” upon reading about – especially – face-to-face meetings between perpetrators and crime victims. Remorse, he’s seen, is not hard for a perp to fake either to a judge or a crime victim. Hardy came to see, however, “that alternative sanctions don’t have to work on everybody to be worth implementing” (p. 243).

If restorative practices work, he writes, to reduce recidivism among even a small percentage of violent offenders, the economic savings alone – keeping these from returning to prison – could in turn fund programming designed to prevent young people from becoming violent in the first place.

Hardy now works for the FBI as a special agent, focused on white collar crime.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), the social ministry expression of a dozen ELCA (Evangelical Lutheran Church in America) congregations in Austin, Texas. I’m the author of There is a Balm in Huntsville: A True Story of Tragedy and Restoration from the Heart of the Texas Prison System (Walnut Street Books, 2019). Readers describe it as “compelling,” “inspiring,” and “well written.”

I’m also the author of Just a Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common Good (ACTA-Chicago, 2014), which traces the history of economic inequality in American society. Reviewing Just a Little Bit More, journalist Sam Pizzigati says, “Anderson, above all, writes with a purpose. He’s hoping to help Americans understand that an egalitarian ideal helped create the United States. We need that ideal, Anderson helps us see, now more than ever.”