Julie Sampson's Blog: Writing Women on the Devon Land

March 18, 2023

Finding a Forgotten Devon Author's Grandmother; Who was ...

Finding a Forgotten Devon Author's Grandmother; Who was Edith Dart’s Granny Jane Sampson?

Lanes, distant moor and ‘Lydcott’, a farm

Lanes, distant moor and ‘Lydcott’, a farm (once home of my mother Clarice Green Sampson) in area of

South Tawton, Taw Green & Sampford Courtenay

Cover of PlayBook Sareel

Cover of PlayBook Sareel

Writing the Devon Rural

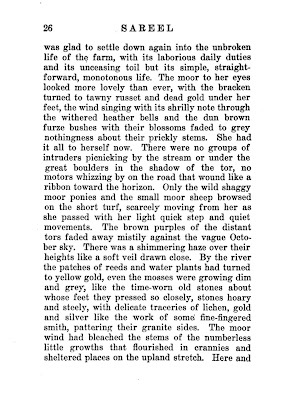

It was a long low house, with whitewashed cob walls and a thatched roof, cowering underneath the shelter of a tor, with only a little patch of garden ground, roughly fenced in, separating it from the open land that stretched away from it on either side. On one hand there was cultivated land that had been snatched from the jealous moor in other days, when public rights were less authoritative than at present; but it was a small portion only, kept from returning to its wild state by constant toil and unremitting efforts. The granite boulders pushed through the surface everywhere, the garden was no more than a handful of earth above it, where only hardy plants and a few straggling bushes might survive (From Sareel, Edith Dart)The vivid description of a farmhouse on the edge of Dartmoor comes from Sareel , a novel by Edith Dart, published circa 1920.

As I’ve already noted in earlier posts about this more or less forgotten Devon author, as yet Sareel is the only one of her several novels I’ve been able to read. Like the fiction of Dart’s close friend MP Willcocks, this story and I’m assuming most, if not all, of her other novels, Sareel, is well and truly bedded down in and around the moorland landscape which, rimming the northern horizon of her Crediton home, must have been a formative influence and inspirational force for the young writer and then later, a potent location providing a never-ending physical and sensory descriptive backdrop for the gentle romance tale of her young fictional heroine.

Views of Dartmoor ridge from places

Views of Dartmoor ridge from places near South Tawton/ Sampford Courtenay/and Taw Green

The farmhouse where young orphan Sareel is driven as she leaves her orphanage home is located on moorland’s liminal edges, a place which had ‘only a little patch of garden ground, roughly fenced in, separating it from the open land that stretched away from it on either side’.

Another passage near Sareel’s opening evokes a farmhouse kitchen:

She went down to the great stone - paved kitchen, with its huge open fire - place and fire of logs on the hearth , above which hung on chains great pots and kettles that she was soon to find very heavy to move and fill. There was a black oak dresser, laden with crockery and winking brass candlesticks, and huge cupboards let into the wall on two sides of the room . Sareel wondered timidly if she would ever get to learn where everything was kept.Reading the novel I began to wonder Edith where gained her inspiration for her fiction’s backdrops; was she just drawing on her own imagination, or more likely from her own observations of the landscapes with which she must have been familiar from jaunts out and about on and near the moor? Or, could she perhaps have more specific locations in mind, taken from places she herself knew, or knew of, through her parents’ tales about them? Fiction of this time set in rural Devon locations by women authors is rare (at least in terms of the writers we know about; there were more female novelists out there, but they and their books have long been forgotten). Speaking from the point of view of a reader who has memories of farming places it’s a revelation for me to be able to read novels written by Devon women about individuals from the past whose backgrounds are similarly countrified.

Edith may have been influenced by her friend MP Willcocks, whose family had been yeomen farmers in Devon for generations, showed personal knowledge of farming life in her novels - and although their names are often changed or swapped for one another’s - people and places in her fiction appear to be directly taken from real people and places in her Devon rooted life. For example, in her first novel Widdicombe the places and characters are very much fictional transformations of moorland or parishes near her home at Ivybridge.

Common Names

I was thinking about the fictional Devon based scenes-capes conjured by Edith Dart whilst whiling away a few hours delving into one branch of the author’s paternal ancestry. My interest was partly because as literary researcher there is often fascination with the background life of the subject, including an understanding of their own family. And in Edith’s case my academic motivation was promoted by a more personal curiosity. When I first posted about Edith I was intrigued to find that we shared a grandmother’s name: her paternal grandmother was called Jane Sampson; my paternal grandmother was identically named Jane Sampson. Could there be an ancestral link? Could the two Janes be connected? Did Edith’s and my family have a close link? The latter possibility was soon put aside. Edith’s Jane and my Jane, no not related: our family’s Jane Sampson was actually her married name; whereas Edith’s Jane Sampson, her father William Dart’s mother, was her maiden name.

How many generations back?

But for centuries back my/our Sampson family has been deeply rooted in the parishes of mid – north Devon, and given that Crediton was Edith’s home town, it seemed logical that her father’s Sampson ancestors may have also sprung from these parts; so it’s feasible the two family clusters are connected. But, if so, how? And when? Luckily, as hundreds of other people with access to the brilliant various online genealogical tools, I’ve already spent hours and hours tracing my father’s paternal predecessors. Although there are still many gaps in our Sampson genealogy, one side of this genealogical puzzle was semi-half complete.

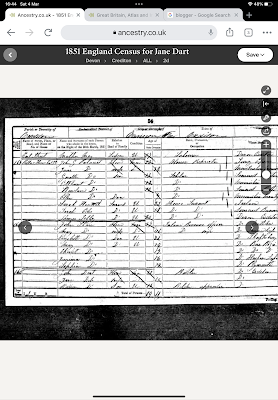

Amateur genealogists love any excuse to loiter in the shadows of genealogy so I began to delve into Edith’s ancestry, looking into the immediate paternal branch of her father’s mother. Who was Edith’s Jane Sampson? Where was she born? There were clues… On the census of 1851 Jane is listed living in Crediton along with her husband, Edith’s grandfather John Dart.

Census 1851 Crediton showing Jane Dart (Sampson)

Census 1851 Crediton showing Jane Dart (Sampson)The couple had married in 1814. According to the census, like John, his wife was from Crediton. However experience has taught me that the given matching of name and place of origin on a census is not necessarily proof of anything, especially of place of birth or baptism. I needed to widen the exploratory net. Was this Jane Sampson really from Crediton?

I went off on a genealogical diversion. Although others had already researched Edith’s immediate family these studies didn’t trace her Sampson grandmother branch.

But when I logged into Ancestry and browsed through related family trees it was soon clear that several others have already researched Edith Dart’s Sampson branch. Thus, here, to some degree I’m indebted to and repeating what I’ve found on those trees; where and when possible (because trees on Ancestry need to be checked as there are often notorious errors) I’ve endeavoured to verify the facts. It’s not always possible though, as frequently with the large families in the rural communities of C18/19 Devon there are complex multiple instances of children with the same name; ie first/second cousins and it’s not simple to work out which branch of the family the individual is from.

For this study I’m also indebted to another literary member of the Devon Sampson family. Fay Sampson has meticulously traced her own Sampsons and has constructed a brilliant website about them.. It is her investigation into the earliest of her own Devon Sampsons back in the vicinity of Winkleigh that has enabled me to hazard a guess about one possible ancestor from whom I think logically all these other Sampsons may have sprung. Of that more later…

Trees just east of Winkleigh looking over to Dartmoor

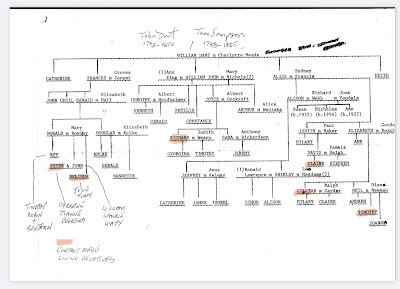

Trees just east of Winkleigh looking over to DartmoorWilliam Dart’s mother Jane

So we begin with William Dart, Edith the author’s father, a local builder from Crediton, born in 1833 who was son of John Dart, born in 1792, who had married Jane Sampson. As noted above Jane and John along with their son William, aged 16, ‘builders apprentice’ are named on the 1851 census; Jane, 61, is three years older than her husband. The 1841 census ten years before has the couple, now both the same age (45), with five children – the I believe youngest sibling William (Edith's father) is eight. In other words there appears to be some discrepancy in facts about Jane’s age.

As I said I’d already done a bit of digging and had a bit of a hunch that rather than being born in Crediton where she spent her married life, Jane may have come from a branch of the Sampson family who for several generations had rooted in the parish of South Tawton just east of Okehampton. So it was with some satisfaction that I came upon a Dart family tree naming Jane and laying out a retreating trail of South Tawton Sampsons. And, oh brilliant (!) the extending familial surnames tree took in those who also pop up in our family line – Lang; Gregory; Paddon; I felt I might be getting closer!

South Tawton Church & Church House

South Tawton Church & Church HouseThere were a few other possible Janes, but the folks on Ancestry trees seemed mostly in agreement. And after a bit more exploration the tree seemed to make a lot of sense. Daughter of William and Frances Sampson (nee Gregory, baptised in North Tawton), Jane was baptised in South Tawton in 1789, second eldest child of a large family. The siblings are all recorded: Robert (1785); Jane (1789); Mary (1791); John (1794); Oliver (1796); Fanny (1800); William (1893); Elizabeth (1806); Caleb (1809); Aaron (1812); and Maria.

Who were they? Where?

First I want to establish the basic line of what I believe to be the kin-connection between Edith Dart’s Sampson branch and our Sampson branch; in those days the latter were well and truly established yeoman farmers in nearby Broadwoodkelly. I’d followed the male line back to the end of the C17 and there’s evidence they were in the parish and nearby other parishes centuries before this.

The following will not be a definitive genealogy, far from it, the ancestral lines are too confusing and convoluted, with several possible divergent familial branches; but putting it out here may one day attract another Sampson historian; someone who can hopefully tease out the intricacies of the mid Devon rural genealogical mazes more than I’m able to.

So here’s the outline of the Sanpson tree that descended to Jane Sampson of South Tawton as it seems to proceed:

Jane’s mother Frances’ husband William Sampson, also from South Tawton, was son of another William. It looks as if the elder William had moved over to South Tawton from Winkleigh.

William’s father Caleb Sampson’s parents were from nearby Broadwoodkelly, and that’s where our family’s Sampson branches, from whose descendants Edith’s and our Sampson clusters merge, may meet up. It’s a retreating line of approximately six generations.

The supposed common ancestor, two more generations back, an Edmund Sampson, born in 1615 (probably) son of another Edmund Sampson married Dorothy Brocke, in Broadwoodkelly in 1644.

As Fay Sampson explains,

‘There are intermittent records there [in Broadwoodkelly] from 1609, which include the baptisms of Edmond, son of Edmond Sampson, in 1615, and George, son of Edmond Sampson, in 1620. Edmond senior died in 1626. There is then a gap in the baptismal register from 1635-54.’ (See Fay Sampson Family website).

Fay surmises that her own forefather, John Sampson, (who happens to be from the same branch as that of Jane Sampson, our erstwhile Edith’s grandmother) – and for whom there seem to be no other recorded baptisms - most likely was a son of this Edmund:

‘This includes the period around 1650 when we would expect John to be born. When the register recommences, there are baptisms for three children of Edmond Sampson, presumably the one born in 1615: Edmond 1655, Richard 1657, and Sarah 1660. It is likely there were more children born before them. From the late 1660s there are children for William Sampson, and in 1678 for Robert Sampson. Both of these could be older sons of Edmond, and it is possible that John was, too’. (Fay Sampson’s site)My supposition, similarly to Fay’s, is that our Sampson branch’s ancestor may well have been the Robert mentioned above, who could have been, like John, another son of Edmund; but like him, his record is missing in the Broadwoodkelly records gap. (It’s beyond the scope of this piece, but our Sampson branch in BWK comes to an abrupt halt with a Simon Sampson. I’ve spent years trying to establish Simon’s birth parents, and at present Robert seems the most likely candidate to be his father).

Anyway, here we can catch up with John Sampson, probable son of Edmund of Broadwoodkelly (forefather of Fay Sampson and Edith Dart’s grandmother Jane Sampson). This John married Grace Paddon. They were parents of five children including the Caleb Sampson listed above. Thus the line from which our Crediton author Edith probably stems descends from John through Caleb Sampson, (his wife ‘Elizabeth’); William Sampson (and his wife Jane Lang); William Sampson (and wife Frances Gregory); Jane Sampson (and her husband John Dart). William Dart Edith’s father, is John’s son.

Broadwoodkelly and Beyond: South Tawton: North Tawton

For several centuries the Sampson family branch from which Edith’s grandmother Jane came were based in South Tawton, a large parish tucked into the edges of the northern moorland folds.

Old photo of Road approaching South Tawton

Old photo of Road approaching South TawtonYou can get a glimpse of the parish during these times from the following passages taken from SOUTH TAWTON PARISH COUNCIL THE FIRST 50 YEARS:

… some were modestly well off, as tenant farmers, small property owners, or as successful tradesmen, blacksmiths, tailors, boot & shoe makers, innkeepers, or, for a few, as skilled manual workers, carpenter, masons, thatchers and so on. But the majority of the population lived at a poverty level, uncertain of work and paid at minimal level when employed (Nine tenths of the women in the parish, (all of the poorest class) are spinners and are regularly supplied by the serge makers with constant employment. Throughout the 19th century the bulk of the population were dependent upon farming for their livelihood, and the majority of men and boys were employed, when work was available, in one or other class of farm work. These labourers lived with their families in small and overcrowded houses in the villages or hamlets of the Parish earning their living from the, often seasonal, work on farms and, at least in the early part of the century, frequently dependent on the charity of the Overseers of the Poor and the Church for the workless periods… The majority of the labourers wives were fully engaged in housekeeping and child bearing and rearing, but, for the first half of the century as Eden describes in the "State of the Poor", there was a sizeable cottage woollen industry in the locality, which employed a few widows, wives, and daughters as spinners and weavers of wool in their cottages. The industrial woollen factory, Pearce's in Sticklepath, employed many more, mainly young unmarried women, from the villages of Ramsley, South Zeal and South Tawton until its closure in the mid 19th century.

A couple of archival documents and censuses suggest possible homes and occupations allowing us glimpses into fragments of the South Tawton Sampson family’s lives. For example, we can work out a little about the lives of William and Frances Sampson and their children. The family seem to have very evident traces in South Tawton during the late C18 and early C19. It might be this William Sampson who took a Mary Gregory as apprentice in 1785. Was he a yeoman in the parish, as were his distant cousins back in Broadwoodkelly where his ancestors were from? Was Mary a close relation of Frances? Perhaps sister, or niece? Land Apportionments for 1847 for South Tawton show a Robert Sampson occupier of a house and garden in the parish; he could be Robert, William and Frances’ eldest son and eldest brother of Jane, Edith Dart’s grandmother. Similarly, an Oliver Sampson rents house and garden at a hamlet of South Tawton called Ramsley and is also renting other property and or land, a garden at Burgoins and four acres at Town Barton and another plot at Holmeses. Oliver also has part share of a couple of plots with another man called George Westaway. Oliver is probably another, younger son of William and Frances, born in 1796. A Mary Sampson is named on the land census as tenant at the large and probably ancient farm at Cesslands. She may be another daughter of the family, or more likely, a widow of one of the sons. Turning to A2A Discovery: an abstract of a Will in 1807 for Caleb Sampson (Cessland/Sessland), may be that of the same William Sampson’s uncle, who was born in 1736. He must be the same Caleb of Sessland, who takes in Samuel Gillard a ten year old apprentice in 1841; a number of other apprentices are taken by Caleb in the years running from circa 1830-up to 1841. I’m tentatively suggesting that an earlier generation of the family – possibly beginning with the Caleb Sampson who seemingly moved over to the parish from Winkleigh (marrying a mysterious ‘Elizabeth’ whose surname as yet is not known - took over Sessland after this marriage. Possibly earlier generations of the family were farming there. These references taken together suggest that, as with the Sampson kin over at Broadwoodkelly, the South Tawton Sampsons were more than likely farming. I think though that the branch of the family whose descendants included Jane wife of John Dart, were, by the time of her generation no more established yeoman of their own farms; more likely the decline in agriculture, which happened as the C19 unfolded, had an impact on them and so during Jane’s lifetime the menfolk were probably tenant farmers, or/and agricultural workers.

Like their cousins over in Broadwoodkelly, by the end of the C18 and early C19 the South Tawton branches appear to have an extended intermarried and complicated family in the parish and surrounding villages; many more hours of research hours are needed to be sure about matching names and places. I’ll have to leave this delight to others (and indeed I believe some researchers have already made studies of this cluster of the family), but for the purpose of this piece I shall restrict further commentary to tracing just a little of the family of Edith Dart’s great grandmother Frances (Gregory) Sampson.

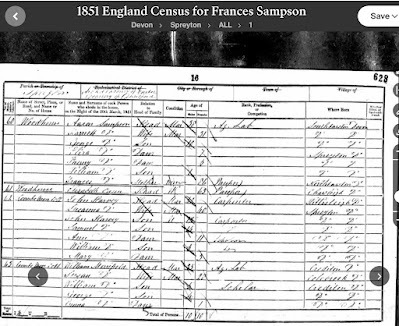

Frances; a Devon author’s Great Grandmother

I've not yet have a chance to find out about Frances Gregory's family back in North Tawton where she was baptised. Gregory is a well-known longstanding North Tawton name and the family have for generations intermarried with branches of the Sampson family. I've concentrated on exploring Frances' life as mother following her marriage. In 1851 Frances Sampson, who I believe was mother of Jane Sampson (Edith Dart’s great grandmother and grandmother respectively) aged 86 is living (or staying?) at ‘Woodhouse’ farm with one of her sons and his family. Her husband, William from the Sampson ancestral line, must already have died. Aaron Sampson is I believe Frances’ youngest son from a family of 10-11 siblings; 58 years old, he is named as agricultural labourer. Wife Harriet and 4 children are named along with Frances, now not only a widow, but rather sadly, also labelled as ‘pauper’.

1851 Census showing Frances Sampson (Pauper) with her family

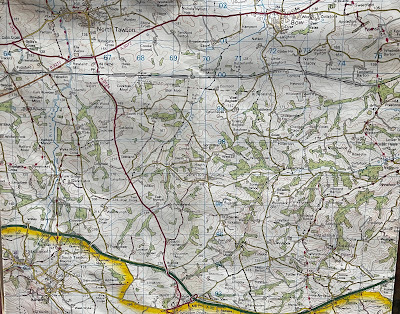

1851 Census showing Frances Sampson (Pauper) with her family Woodhouse is a farm which I think is nowadays designated as in the parish of nearby Spreyton, but it may in the past have straddled several parishes, including nearby Bow.

Scenes around Spreyton Church

Scenes around Spreyton ChurchIn 1842 Woodhouse was about 120 acres. According to one source online Woodhouse was owned in the mid C19 by the Battishill family. Eventually the farmland was assimilated into the nearby farm of Week and the farmhouse used to house farm labourers, which probably explains why the Sampsons were living there. Apparently Woodhouse is reached by a drive off the Spreyton-Bow road and from a path from Week, but back in the years when this Sampson family were there you could probably reach it from another path between Spreyton and Spreytonwood Water road.

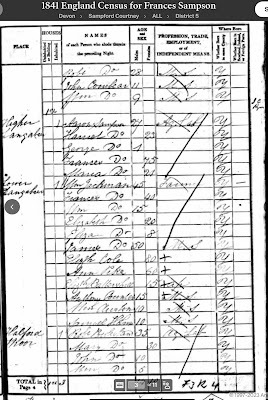

Frances Sampson had probably lived with her youngest son Aaron for many years. She’s listed with his family ten years before, in the 1841 census; the family are at Higher Langabeer farm, a farm bordering Sampford Courtenay some six or seven miles west of Woodhouse.

1841 Census Frances at Langabeer

1841 Census Frances at Langabeer  Map showing both Woodhouse and Langabeer Farm

Map showing both Woodhouse and Langabeer Farm 75 years old, Frances is named with Aaron’s wife, and their son George. There’s also Maria (21), who people on ancestry usually record as Frances’ youngest daughter, but who realistically cannot have been; by 1820, Maria’s baptismal year, Frances would have been well over fifty! I believe Maria must be illegitimate daughter of Frances’s daughter also called Fanny. Perhaps her grandmother took the child in and brought her up… (Interestingly a census sample for 1851 records Fanny Sampson (Maria’s mother), as house servant at nearby Oxenham House).

By the end of 1851 Frances, William’s widow, has died, presumably while she was with her family at Woodhouse. As mentioned above, she was born and married in nearby North Tawton (1765 and 1785 respectively) so had probably never moved far away from her childhood home. (And here, time allowing I’d love to go on another genealogical recce to explore the Gregory family descent, for our Broadwoodkelly Sampsons also interrelate with the family).

In 1841, Jane, Frances’s eldest daughter was, as I noted earlier in this piece, married and living in Crediton. Jane is about 45. The couple have five children: Samuel (20); James (15); Maria (13); Elizabeth (11) and William (who years later would be father of Edith Dart), their youngest, who is eight. Presumably, Jane, with William and some of his siblings would have travelled across from Crediton to the farmhouse over in the rural backwaters near Sampford Courtenay, to visit her mother and brother and family. Ten years later, in the early 1850s, journeys to visit Frances over at Woodhouse farm would have been shorter. By then William’s grandmother was nearing the end of her life; her youngest son and still living with his parents in 1851William could easily have accompanied his mother as she spent time with his ailing grandmother back in South Tawton.

Finding the Farmhouses

As noted in Remembering Edith Dart Edith Dart’s immediate paternal family, especially her father William, were established and increasingly respected local builders; but her agricultural farming family legacy linked with her Sampson grandmother may have influenced her as writer when she was growing up providing backdrops and backstories for the fictional characters she created. Although Edith’s grandmother on the Sampson side had died in 1865, several years before her youngest granddaughter’s birth in 1872, Edith’s older sisters must have known Jane as at the age of 72, in 1861, their grandmother was still living with her son and his young family in Fountain Court, Crediton. I guess there were cousins from the extended family still living in and around South Tawton who her father and his kin may have kept in touch with. I imagine that Edith Dart picked up the tales told her by her father about his visits to his grandmother’s home in the farmhouse back in South Tawton and he may also have related folk tales about forefathers and foremothers in the rural hideouts of the Devon villages, hamlets and farms lying under moor’s rim.

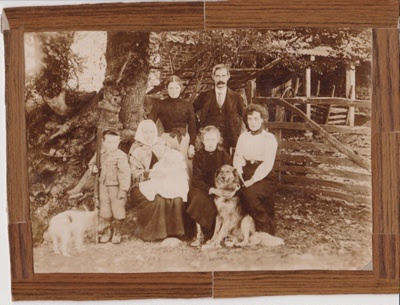

I know as poet sometimes I return to the tales told me about people in my parents’ families who I never had the chance to meet. And amongst the vivid memories of special places in childhood we all carry mine include a farm house in the depths of mid Devon, where my own father Laurence Sampson loved to take us as he rekindled his own nostalgia for the place. The farm had a mixed effect on me. Dark and brooding and so atmospheric, yet at the same time its inhabitants, Dad’s first cousins, always gave us a welcome, and their Devon teas were to die for. The obligatory huge open fireplace pervaded the place, gave it its sense of unfathomable history; its atmospheric mystery. We were cocooned within the crocks and fire-irons around which we all sat brooding as our father and his cousins caught up with the latest farm gossip.

Coulson is situated between the villages of Winkleigh and Broadwoodkelly and is still as far I know a working farm. One of the many such inhabited by a long stream of Dad’s farming forefathers - where back in the 1950’s his cousins John and Henry and John’s wife Edie still farmed and where (though I wasn’t consciously aware of in those days), a tangled family network unfolded.

One of the family photos at Coulson, where Sampsons and Paddons lived and farmed. The photo includes our grandfather Samuel Sampson, his sister Jinny

One of the family photos at Coulson, where Sampsons and Paddons lived and farmed. The photo includes our grandfather Samuel Sampson, his sister Jinny and our great grandmother Nancy Earland/Sampson/Paddon

The family included Dad’s grandmother, Nancy Earland Sampson Paddon, who I assume moved to Coulson after marrying Bartholomew Paddon following her first husband John Sampson’s death. Meanwhile, Nancy’s daughter Jinny married Bartholomew’s son, another Bartholomew. Both Nancy and Bart. had families who in turn intermarried and had their own children. A complex affair! (And they say modern family set ups are complicated!) Coulson may have been inhabited by one or other of the family networks (Sampsons/Paddons et al) for many generations. Certainly Dad often spoke of his grandmother, my great grandmother. Our family is still in possession of a couple of evocative old photos of the farm including at harvest time, with members of the extended family gathered around, eating, chatting, laughing.

When we visited in the 1950s it was as if we’d returned to the world of our departed kin. The long table covered with white damask and spread with Devon cream-laden tea - scones, Victoria sponge, junket, jellies and steaming tea. All set in front of a long bench, a delight for young kids. Pewter pots and pans hung round the walls. Portraits of Victorian clad ancestors on the whitewashed walls. And in the here and now of then, Dad’s cousins, one swarthy, jocular and friendly, the other a silent broad shouldered man, whose Devonshire accent when he spoke was so broad even we brought up with the dialect could not follow…

But I must not let myself get carried away… I just wanted to explore how even a rural Devon family background can remain in one’s heart and pop up sometimes needing to be resurrected as fiction, or in my case, as poetry…

I must return to Edith’s novel Sareel.

Sareel, the young girl heroine orphan in the novel, herself utterly immersed in the physicality of moor through her new home and work as farm servant, soon finds the local Genius loci has entered her very being. See for example the following page from the novel’s early chapters:

From Sareel

From SareelThe woman who created her young heroine knew first hand how Devon’s landscape can hook you and I believe, like her great friend Mary Willcocks, Edith Dart took her father’s forebearers and their countryside homes to heart, transforming her own observations and her father‘s memories and nostalgic recollections into the beating centre of her romantic Devon moorland novel. Sareel must have made an impression on the literati of her time for the book was apparently made into a film. I just wish I could locate it. Perhaps someone will?

I can’t judge the literary quality of Edith Dart’s other novels for reasons I’ve already explained. I'd need to have a chance to read them, which I hope will happen one day. But isn’t it odd, isn’t there something amiss when novels by male authors of her, or of her near contemporary male writers such as Eden Philpotts, are remembered, praised for the way they record and bring local characters and places to life and indeed, are still in print. For example see this assessment of a novel based in South Zeal by the acclaimed Eden Philpotts:

Oxenham house was brought to life by EP The Oxenham Arms and Captain John Oxenham have been written about in many, many books and novels over its 850 years of existence . Charles Kingsley's "Westward Ho" describes how Oxenham and the book "The Beacon" by the author Eden Philpotts was entirely written about and around The Oxenham Arms and a fictional barmaid Lizzie Denshaw and the beautiful and strong characters of the village of South Zeal …https://www.theoxenhamarms.com/historyI understand that as I write up this post there’s an amazing and long due project afloat to bring Edith’s friend M P Willcocks to the attention of contemporary readers and interested local communities. My hope is that eventually a similar gathering of community and attention will resurrect Edith Dart and her writings from the dark basement of the archives where they currently reside; perhaps this post may encourage someone to bring her work into print again, and so back into the canon of C20 novels.

One day perhaps our missing legacy of as yet abandoned Devon women novelists from this time will be lifted out of the shadows again. ... Still, if nothing else, it’s been fun to have an excuse to follow the genetic trails of the Devon Sampson clan as it leaves us fast-receding into our home landscape’s past.

(If anyone coming across this is interested in the Sampson family of Broadwoodkelly and its links with Jane Sampson's ancestry) I've set out the possible ancestry on Tribal Pages. Just contact me for details.)

Thanks for reading this post. I hope you enjoyed it. Please follow!© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

February 19, 2023

Edith Dart; A Devon Writer's Journey to Publication

Edith Dart’s Writing

Crediton Church Christmas Tree Festival 2022.

Crediton Church Christmas Tree Festival 2022.'She heard one voice between her chants, from

matins to compline.

It sang not canticle nor psalm.

It drowned the Mass divine.

"Can there be sin in Christendom, Mother of God,

as mine?"

From 'A Sin' in Earth with its Bars & Other Poems,

by Edith Dart

Contexts; Fiction and Poetry

Edith Dart published short stories, novels and poetry. Her work also appeared in a wide variety of contemporary journals and anthologies. There’s also a scattering of reviews about her work published in various contemporary papers and journals. Remembered especially for her novel Sareel which was apparently made into a film (but unfortunately as yet I’ve not found any reference to it) according to her friend Mary Patricia Willcocks Edith apparently gained national recognition for several of her books and for her poetry.

As yet I’ve only had the opportunity to read one or two of Edith’s short stories printed in journals accessed via archives. I’ve also read the novel Sareel her last published and apparently most popular novel, as it’s available via google play books; but it’s proved very difficult to get hold of any of the other novels, which are in the out of print, rare books category; although one or two local/national archives hold copies of some of them, the novels are not necessarily easy to access, unless you are close to said archive or/and have the funds to order copies of sample pages. Currently I’m not in a position to do either. I’ve been so lucky to have some generous offers of help out there - freely given – which has enabled me to read the archival documents explained below. Devon Record Office does hold at least one copy of several of Dart’s books, but I’m not sure it’ll be me that gets to read them.

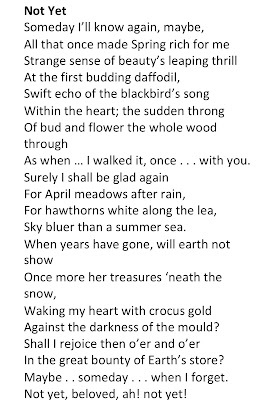

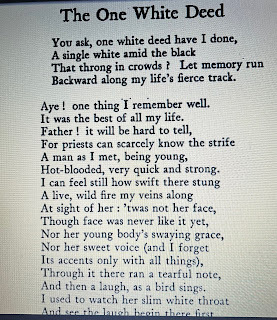

I have also browsed through a few of Dart’s poems published in contemporary journals and her poetry collection Earth with its Bars and Other Poems (pub 1914, which, like Sareel is available via Google PlayBooks). Given the era during which it was written and published, this collection would be read now within the aesthetic style of traditional late Edwardian poetry. Not even slightly taking up the more experimental modes of the early modernist or impressionist poets such as H.D. (whose first collection, Sea Garden would be published while the poet was staying in Devon, in 1916, just two years after Dart’s), Dart’s poems are conventional in tone, subject and form, often imbued with the mores of Christianity (which had obviously formed the roots of Edith’s early years). However, I think some of Edith Dart’s poems in Earth with its Bars and elsewhere are more complex than this. Such poems as ‘The One White Deed’ and ‘Not Yet’ (published 1920 in The English Review - see below) are reminiscent of other of the author’s near contemporaries such as Charlotte Mew (1869-1928); Mary Coleridge (1861-1907) and Christina Rossetti (1830 - 1894), all of whose work is deceptively subtle and all of whom had Devon connections.

One characteristic the poems of Coleridge, Mew and Rossetti often share is the hint of a hidden narrative. Enigmatic poems such as ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ (Mew); ‘The Fiery Dawn’ (Coleridge); and ‘Winter: My Secret’ (Rossetti) are echoed in ‘Not Yet’ and ‘The One White Deed’, both of which are suggestive of a half-told story, perhaps a secret love relationship. The latter poem’s narrative persona is, perhaps surprisingly, male; but in such it is a poem that resembles several of Charlotte Mew’s including ‘The Farmer’s Bride’, which also features a male persona:

Opening of 'The One White Deed'

Opening of 'The One White Deed'There’s so much potential for future research in studying links and correspondences between these poets, both their lives and their work, but it’s beyond the scope of what I’m trying to cover here.

Several contemporary reviews tell us that Dart's poetry collection Earth with its Bars was well received by the poetry establishment:

‘Earth and Her Bars,… is the work of a Crediton lady, Miss Edith Dart, and deserves more recognition locally than it has received, for it has met with the general approval of critics. “The Literary World”, for instance says that the poetess, “apart from the technical mastery of rhythm, possesses that essential gift of touching to ecstasy the heart’s inmost chords which call poetry”. (Western Times, 16 March 1915)

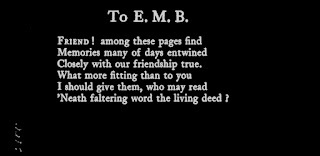

Before, regrettably, leaving further comments about her poetry I must just comment on Edith Dart’s dedication in Earth and its Bars, whose wording is itself somewhat mysterious. The book is dedicated to E.M. D., who is addressed as a friend. I don't know the identity of EMD, perhaps her readers were not supposed to. Curiosity however always gets the better of a keen researcher and though it's only a hunch as yet, when I went on an online family history recce a possibility suggested itself. There was a local Crediton family called Borne who according to the relevant census lived in the High Street, quite near to Edith Dart's home before she moved to The Orchard. One daughter was named Edith Mary Borne. Her birth date was in 1898 so she was a lot younger than Edith the author, but I wonder if her namesake may be the mystery friend of the poetry collection. (Interestingly a document of Crediton Board of Guardians (1895) mentions a Miss Dart alongside Miss Borne as applicants for a local post; the Miss Borne mentioned here can not be Edith born in 1898, but perhaps the two 'Bornes' are related?)

Dedication to E.M.D. frontispiece Edith Dart's collection of poetry

Dedication to E.M.D. frontispiece Edith Dart's collection of poetryEarth with it Bars and Other Poems

I must emphasise, my firsthand reading of Edith Dart – especially of her fiction is of necessity limited. But I did so enjoy the novel Sareel! Ok, it’s ‘olde-worlde’ and to us contemporary readers archaic in style and theme; yet the story still engages. The tale of a young orphan, Sarah Hill, brought up in a local workhouse who becomes servant to a farmer and his wife in the depths of Dartmoor - whose characterful landscape becomes a backdrop to the gently dramatic love-interest story that emerges. Like many of the novels written by Dart’s friend Mary Patricia Willcocks (which were published over several decades, from about 1905), Sareel’s heart is immersed in the moors of Devon, and its surrounding hinterlands; these two authors conjure for us the wild remoteness of Dartmoor, as it once was:

wide open moor broke upon her in great, undulating, unfettered spaces, wave upon wave of soft misty browns, merging by infinite gradations into dull purples and quivering violets, until it reached the sky-line…’(Sareel).

There is so little fiction set within Devon’s landscapes written by local women writers during the decades of the early C20, so for any reader who loves this part of the Westcountry, along with Willcocks’ fiction, and one other local woman writer of romance fiction (more below), Sareel is well-nigh a stand alone novel. As such, it’s a book that we ‘Devonians’ should treasure. It’s not easy to make a judgement as to comparisons between Dart and Willcocks’ work, mostly because there’s little opportunity to actually read the former’s novels, whereas thanks to the diligent research of Bob Mann, Willcocks is gradually beginning to spark renewed interest amongst literary aficionados. Given this proviso it may be unfair to suggest that Dart’s novels do not quite come up to the subtle and complex layerings of psychological character portrayal evident in the fiction of her friend. I think from my limited reading so far I’m more inclined to compare Edith Dart’s writing with her near neighbour and contemporary novelist Margaret Pedler, publication dates of whose books roughly correspond with the years during which Dart’s novels appeared. I’ve no idea if the two women knew one another but they were both born in the same decade, the 1870’s and their homes were only say seven or eight miles apart, Dart’s in Crediton and Pedler’s near Zeal Monachorum, so surely they must have at least known of one another’s work. Pedler became a household name after the success of several of her many ‘romance’ novels, in particular The Hermit of Far End, which was apparently published in 1920, the same year as Dart's Sareel. Mills & Boon published several, if not most of both Pedler's and Dart's novels.

Dart’s and Pedler’s work led me to think more about these women novelists whose books published by Mills and Boon are now definitively labelled as default roman fiction. I want to clarify something that’s been bothering me for a while when thinking about several Devon associated female fiction writers of this early C20 generation. I wonder if, too often, we look back and, noting that a novel first published at the time was under the label 'popular romance', make an automatic presumptive prejudiced judgement about the text’s quality, ie its ‘not so good as more ‘literary’ or ‘highbrow’ novels.

Whilst researching Edith Dart I happened upon the intriguingly titled blog Furrowed Middlebrow, which helped put my own concerns into words. Scott, The writer of the blog documents and publishes ‘British women writers who published at least one volume of fiction during the years 1910-1960’. I’d not come upon the secondary text it mentions but the blog is evidently indebted to an academic study text called The Feminine Middlebrow Novel 1920’s – 1950’s by Nicola Humble. What defines a ‘highbrow’, what we’d now term a ‘literary’ novel? How does the reader distinguish between it and another book which has been designated as ‘middlebrow’, or ‘popular’, ie judged as less worthy? …..

I’d not realised that when Mills & Boon began to publish during the first decade of the C20 rather than specialising in the romance genre for which they became famous, they were general publishers, although the first book they put out (perhaps ironically) was a romance:

Mills & Boon wasn't all about lust and amour at first - when the company initially launched, it was a general fiction publisher, turning out books about everything from travel to craft. The first book it ever published was prophetically a romance book - Arrows From The Dark, by Sophie Cole. Critics gave it a glowing report and by 1914, 1,394 women had bought a copy. The writer went on to pen another 65 thrilling titles for the publisher during her fruitful career. (Mills & Boon History)

So, just because a novel published during these early years of the C20 was through Mills & Boon, as at least a few of Dart’s were (and most of Margaret Pedler’s), it doesn’t necessarily follow that it was the kind of narrative defined by our C21 literary understanding of 'romance novel'. Such is suggested in several contemporary reviews of Edith Dart’s novels, of which more below. Ultimately it's impossible to categorise or definitively assess a novel’s 'true' quality, for to begin with, readers change with the times and as the Furrowed Middlebrow blog suggests, a novel that might at one period be understood as brilliantly literary or highbrow, read say a generation later by readers with different preferences and mindsets, might well (as with pop music?) failing to pass the latest literary fashion, be delegated to the canon’s ‘slush-pile’ (ie from thenceforth be labelled as ‘popular’ or ‘middlebrow’).

With these musings in mind I’m now going to try and trace a little of Edith Dart’s writing journey - with the proviso that, as I noted above, it's not easy to locate her primary texts and there’s not much easily located extra material about her out in archives. But luckily I did find a couple of fascinating files in archives which do reveal a little about Edith Dart's own literary journey.

The Literary Journey

I imagine that towards the end of her life, self-defining with the status of ‘novelist’, Edith must have felt she’d achieved her literary ambition. But reading between the lines of a handful of archival documents I’ve stumbled on which feature her I think this Crediton author’s literary journey toward that goal was a long one and that, like so many other women writers before and since, she had quite a struggle to achieve her literary goals. (There is nothing new in the publishing world as many

When she presented the bouquet to his wife, at the time of General Buller’s homecoming (see Remembering Edith Dart) Edith must already have been writing seriously, sending out and getting poems and short stories published in a variety of magazines and anthologies. A spell of online browsing will turn up several archival references to her work appearing in a number of contemporary magazines and anthologies. However in 1900, as far as I know she did not have a full poetry collection or novel published, nor apparently did she for several more years, probably not until after moving into her last home, The Orchard (See Remembering Edith Dart). An intriguing series of letters Edith sent to one of the UK’s then leading literary agents unfolds the story of a rather tortuous trail, a writer plying her trade, reaching out to at least one agent for advice and help to get her novels and poetry collections out there and published. I’m grateful for the kind assistance given me by staff at Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections & University Archives Northwestern University – especially to Jason Nargis – for his (and their) generosity in helping me locate this file of precious archival documents and granting me permanent to quote from the file; the letters provide the researcher with unique information helping to tracing an author’s difficult route to success.

The letters were written intermittently by Edith between March 1906 and 1912. They were penned during the period when, following her father William’s death, the Dart family moved from 128 High Street in Crediton to The Orchard just north of the main street; there is a break in the letter sequence which may be explained by the Darts’ move up to their new home. The letters were sent to James B Pinker, who was a leading literary agent for many of the leading British and American writers of his age. A giant and pioneer in the field, Pinker is considered to be one of the first literary agents, at least as the modern literary world understands the role.

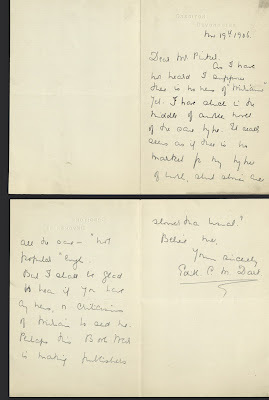

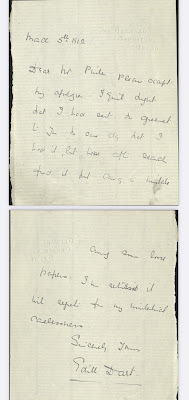

Letter from Edith Dart March 1906 to James B Pinker

Letter from Edith Dart March 1906 to James B PinkerReproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections

and University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries

Edith’s letter of March 7th 1906 indicates that this is not the beginning of their correspondence. Indeed, her words suggest she has been assiduous in seeking the help of the agent for several years. She notes there had already been ‘an agreement’ between the two of them and is apparently seeking a formal end to their contract:

‘Although our agreement was virtually at an end some time ago, I believe that it has never been formally put and it would perhaps be as well that that were done: perhaps you would just send me a line to that effect sometime. I was very sorry to be such a disappointing client, my only plea is that I suffered too!’ (From Edith Dart letter to James B Pinker 7th May 1906)

Evidently in 1906 - when she was 34 - Edith Dart was not feeling at all fulfilled or happy with her writerly achievements. Reading between the lines, although she tries to make light of it, she’s not entirely satisfied with the help she’s (not) had from Pinker. It’s not only the fact that her novel/s haven’t yet been taken up by a publisher that bothers her; Edith tells the agent she ‘has to peg on to the ‘bits’ that help bring me pennies’. Although she’s desperate to finish the ‘long tale’ that has ‘been so long on the stocks’, she implies it is the more tedious everyday graft of writing formulaic pieces for publishing in paid magazines and journals that she must persist working on.

Edith writes to Pinker again two months later, 23rd May 1906. She’s apparently sending him the ‘final’ chapters of a novel, for feedback and advice: ‘I hope that you will think well of them, and that somebody else will too!’The novel is titled Miriam and is, one assumes, the ‘long tale’ she mentioned in her previous letter. She also adds a postscript asking Pinker to ‘show Gillespie this collection of verse for Mclure’s’; ‘some of it’ she adds, ‘has been published before, mostly in the Pall Mall Gazette’. (‘Mclures’ I assume must have been a misspelling for McClures; McClures Magazine was an illustrated monthly journal at the turn of the C20. Sometimes the magazine published a serialised novel. I haven’t had a chance yet to explore further about McClure’s links with Edith Dart but there are various online sites featuring the publication, so more research may turn up something). The letter of May 6th suggests that this time Pinker had responded to the earlier communication and made editorial suggestions for her revision of said manuscript. (Unfortunately we only have Edith’s side of the written interchange between them).

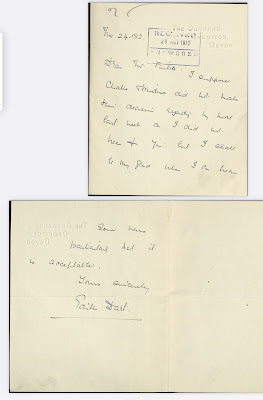

Letter from Edith Dart to James B Pinker May 1906

Letter from Edith Dart to James B Pinker May 1906Reproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections

and University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries

Presumably this time Edith’s perseverance (subtle reprimand of the agent) got her somewhere, for eventually Miriam was to be her first published novel, making its appearance in 1908, two years after this letter was sent to the agent. Perhaps this time round Pinker did after all come up trumps, putting the effort into helping the Devon novelist on her way to ‘proper’ publication. However, whatever the means, the eventual satisfactory route to publication of Miriam, that first novel, two years later was not handed to Edith on a plate.

In August 1906 she was anxiously chasing her agent again:

‘I suppose there is no news, or no good news from Constable, or you would have let me know? … I am most anxious to hear, but don’t want to hurry them into sending bit back, if they are inclined to like it.’

In this letter we find more about Edith’s current writing projects and, putting two and two together (with actual dates of novel publication at hand), can work out the probable title of the latest ‘long tale’ she says she’s ‘lately’ working on whilst waiting for feedback about the earlier novel. This must be the novel Rebecca Drew, which came out in 1910, two years after publication of Miriam.

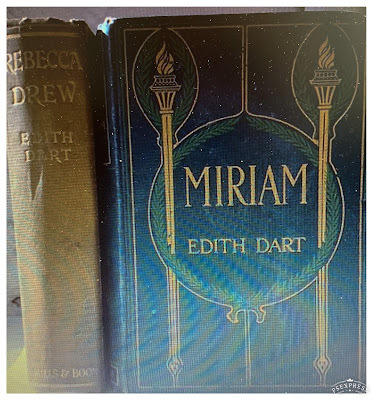

Covers of novels Miriam and Rebecca Drew by Edith Dart

Covers of novels Miriam and Rebecca Drew by Edith DartBut in 1906 all that was still to happen. Three months after the August letter Edith wrote to Pinker again. Rather than typed, as were the earlier ones this letter was handwritten, with what appears a hasty scrawl.

Edith Dart letter to Pinker 19th Nov 1906 Reproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries.

Edith Dart letter to Pinker 19th Nov 1906 Reproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries.She’s still convinced that there is no market for her type of novel and is markedly discouraged that Miriam has not been taken up by anyone. Confirming she’s ‘in the middle of another novel of the same type’… Edith adds, ‘it really seems as if there is no market for my kind of work … not popular enough’, and also, reflecting on the current political context, she wonders whether ‘this Boer War is making publishers slower than usual’ (perhaps meaning the South African Wars, as the Boer War ended 1902?).

The agonising wait continued; there were more set-backs yet to come.

Early the following year, January 4th 1907, there’s still ‘nothing of Miriam’ and Edith is evidently trying to resign herself to the unsatisfactory situation: ‘there will be nothing to hear, Alas’; but she is still persevering, posting her now just finished manuscript of the novel which I believe must be Rebecca Drew; she says she’ll ‘be glad to know what he [Pinkney] thinks of it’ and that he will think it ‘ought to be longer but it wouldn’t be despite my best efforts’. There’s a note of desperation in this letter: ‘I do hope the tide is going to turn soon, or I shall have to take up some other work’. (It is hard to know whether she is being serious apropos her financial situation. Although it was a couple of years after he’d died, given the success of Dart and Frances, the family firm (See Remembering Edith Dart) one would assume that her father’s widowed wife and unmarried daughters would have been left with a surfeit of funds. But perhaps not; or was Edith deliberately pleading poverty?

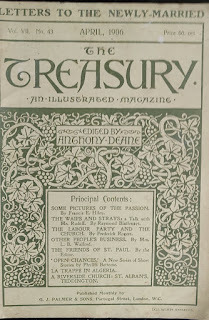

This letter concludes with another query regarding a contemporary illustrated magazine called The Treasury.

Cover of an issue of The Treasury

Cover of an issue of The TreasuryEdith says that Deane, the editor has already published some of her verses and she wonders if he/they’ll ‘care for this’. I’m not sure if she’s referring to the latest fiction manuscript she’s enclosing with her letter to Pinker, or if she’s also (as before) sending Pinker more poems. Again, she ends with a little throwaway comment, her work is not ‘goody’ enough for that magazine; this comment, like her others, is revealing about Dart’s real annoyance /frustration. I get the impression that Edith does not want her work to be considered as romantic slush (indeed she’s derisory about such writing), but that she feels she has to conform in order to achieve publication.

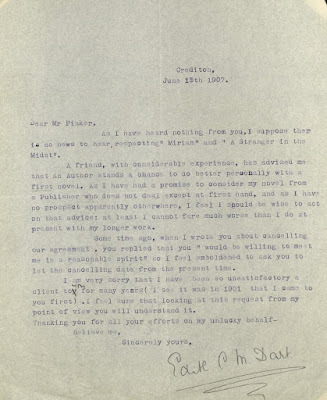

The last letter in the first batch of letters to the agent was written in June 15th 1907. Edith’s patience with Pinker has seemingly run out. She’s effectively terminating her agreement with him. Having had good news from a publisher, who only deals with authors ‘firsthand’ - they have given her a ‘promise to consider my novel’ – and advice from a friend (perhaps M.P. Willcocks), that she should accept that offer, she adds ‘As I have no promise otherwise, I feel I should be wise to act on that advice’.

Letter from Edith Dart to James Pinkey June 15th 1907Reproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collectionsand University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries

Letter from Edith Dart to James Pinkey June 15th 1907Reproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collectionsand University Archives, Northwestern University LibrariesI’m not sure which of her novels she’s referring to in the letter as by now Pinker must be dealing with two of her manuscripts; she names them both, Miriam and A Stranger in the Midst (which I believe to be a first title for the novel that became the writer’s second published one, Rebecca Drew). We find why Dart had decided to approach Pinker again following the initial letter (when she’d suggested an end to their contract); he’d apparently responded that he would ‘be willing to meet me in a reasonable spirit’. However, this time she’s had enough and tells the agent that she’s ‘emboldened to ask you to let the cancelling date from the present time’. Sadly perhaps, rather than challenging the man about what appears to be lack of action on his behalf, she ends with another self put-down; ‘I’m sorry that I have been so unsatisfactory a client to you for so many years’. It becomes clear from this letter that Edith Dart’s first dealings with Pinker were in 1901, that is when Edith was living in the High Street and her father was still alive.

Now there is a long break in the correspondence. It’s March 5th 1912, five years later, when (according to this sequence) she next writes to him. Everything has changed for her; she now has several published novels. It's a short handwritten scrawl again (as are the final letters in the batch), this time on headed paper noting her address as ‘The Orchard’, she’s apologising and sending her agent ‘something’ that she thought in her ‘carelessness’ she’d already done; (but because of the difficult handwriting, I’m not sure what!) I’m assuming it’s another agreement. This second group of Dart’s letters is penned in very untidy handwriting so I’m having to hazard a lot of guesses; (anyone out there who comes upon this and can decipher please let me know).

Letter March 5th 1912 from Edith Dart to James PinkerReproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries

Letter March 5th 1912 from Edith Dart to James PinkerReproduced Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives, Northwestern University LibrariesFrom now on my comments are trying to get the gist of Dart’s communications with Pinker. From these one-sided letters it’s unclear whether their initial contract did end in 1907, or whether, chastened by the writer's criticism of him, Pinker got his act together and pulled some strings for her, thus after all finding a publisher for the novels. I think possibly the latter, but am not sure.

There has been a long break in their exchange, but knowing, with hindsight, that by the time of the letter of March 1912 Edith Dart has at least two novels in print – and probably a third recently published (ie Miriam, Rebecca Drew and Likeness), the success of having achieved publication of a trio of novels must have boosted her confidence as successful author. Engaged in writing her ‘latest’ novel which will be ready, she says, in May, she is evidently returning to Pinker to gain some advice about her next course of action. Near the end of the letter we find the title of her latest manuscript is The Tale of Tamsin (I don’t know if this manuscript was ever published or/and if so, what its final title was).

Edith’s concerns now centre around what kind of narrative mode she’d be best to focus on; her letter reads as if her main impetus is the commercial value of her work rather than its intrinsic artistic value. She is torn between confirming to the requirements of Mills and Boon, whose style she deliberately conformed to in those earlier novels, and who I believe published her first novels; or, perhaps, she wonders, trying another ‘form ‘. (Of course, in connection with my comments about Mills and Boon above, the implication here is that for authors this publisher already had associations with the now established stylistic features of the romance mode).

She also mentions a couple of other possible publishers who could be approached, including Constable: ‘Do you think Constable would be likely to look favourably on my work if we decide to give up Mills and Boon’? (The ‘we’ is perhaps telling?) This reads as if having achieved a degree of success with Miriam, Rebecca Drew and Likeness, her first trio of published novels, Edith is in fear of losing the support of the publisher who has taken her on; she’s afraid to take the risk of approaching someone else, in case. Her attitude toward Pinker has apparently changed; she’s now respectfully trusting of him and reaching out for his advice.

A week or so later Edith writes to the agent again, sending the first few chapters of Tamsin along with a short accompanying note. And then we have the final letter in the series to the Pinker. Of course there may be or may have been others; perhaps if so one day they’ll come to light. As yet I’ve not been able to make out the writing in full, but in this final rather brief note written in November 1912, the tone returns almost full circle to where the letters began, in 1906. Edith’s chasing Pinker for a response again: this time she’s waiting to hear from Chatto and Windus: ‘ I shall be glad when I hear some news particularly if is is acceptable.’ …

Letter 24th November 1912 from Edith Dart to James Pinker

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives,

Northwestern University Libraries

Was ‘Tamsin’ ever published, either with that, or another title? I don’t know.

Perhaps it did, as The Loom of Life (published 1916) … ?

And What They Said …

… I don’t know the fate of Dart’s novel Tamsin, but in manuscript form, it features in the other Edith Dart file I stumbled upon in the archives. This document, along with a selection of reviews from papers and magazines of the time, makes it possible to comment, albeit tentatively, on how Edith Dart’s writings were received by her contemporaries.

The file about Tamsin was located at the University of Reading Special Collections. It’s a Reader’s Report written by Bernard Miall, in June 1916, four years after Dart’s last letter to her agent Pinker Miall was a well-known translator and publisher’s reader for Allen & Unwin. According to one source he was living in Devon in 1925, so it’s possible he knew Edith. I haven’t yet managed to get permission to quote from this document, or reproduce any of it, so my remarks here will be limited to a summary. Calling it a ‘psychological study’ Miall felt Tamsin was serious and well-intentioned – yet ultimately its plot twisting failed to convince and, he noted, required a rewrite. Miall’s reading of the narrative concluded that its heroine's crisis lacked convincing explanation. This reader’s report gives us a synopsis of the book, which seemingly has echoes of Sareel (presumably written after Tamsin), Dart’s most successful novel (and the only one I’ve been able to get hold of). Set in Devon, both of these novels’ narratives swirl around the fate of an orphan; the story in both novels takes place on a farm - a farmer is an important character; also, in both novels, Dartmoor is at the heart of the setting.

Miall’s critique of the manuscript titled Tamsin comes across as somewhat condescending in tone (he assesses the author’s work as ‘improving ‘ and - offering to read the manuscript again if it’s revised - forecasts that Dart might in future write a ‘creditable novel’. Perhaps Edith was unlucky with her reader. As it’s unlikely the manuscript will come to light (unless published under another name), we shall probably never know.

However I’ve found from a newspaper article that Dart’s most acclaimed novel Sareel was published by Phillip Allan & Co., so perhaps it was through Miall's eventual support that her final success was obtained.

Sareel’s success was perhaps guaranteed by one its earliest reviews, published 3rd June 1920, in Brixham Western Guardian. I'd love to know the fate of the mystery novel Tamsin ...

Edith Dart's life and writing must surely become focus of future research for those who, like me, are fascinated with all the gaps in our knowledge about women who wrote Devon in the depths of our county's past...

Postscript; A Few Contemporary Reviews

A New Devonshire Story

Sareel is the title of the new novel by Edith Dart, just published by Messrs. Phillip Allan & Co.. It is in many senses a fascinating problem story, with a vein of intensely human interest running through it from end to end, which cannot fail to grip the reader, who recognise Dartmoor, in the delightfully drawn word pictures amid which Sara Hill’s romantic introduction to life took place, and where eventually she found, in an unconventional rescuer, an ideal life partner. A workhouse reared girl, with a keen love of beauty in her soul, planted amid glorious scenery, day by day subjected to tyranny, invective, and reproach by a virago of a mistress, and ignorant in the ways of the world, finds a champion in distress in a London, visitor, young and impressionable, on whom her primal simplicity casts an irresistible spell, until she becomes a Cinderella to him as the fairy Prince. And here commences, lives tango.

The interception of letters, Sareel’s disappointment, her marriage to the unconventional, Robert Nugent, the writer, who lives alone, in primitive, simplicity, the discovery of the perfidy of her late mistress, her decision to go to her old lover, only to find herself a source of embarrassment to him, and that her young romance had been shattered, her “return out of the darkness and chill of the valley of death and humiliation into the light, an open air, under gods heaven” to the realisation of true love, won at last “out of the tangle and perplexity of the strange mysterious web of fate” have been drawn to life in what may be termed an out-of- the- ordinary type of novel, which cannot fail to please those who are looking for something really worth reading. (See in Brixham Western Guardian, 1920, in British Newspaper Archive)

Here’s what they said … a few other quotes from contemporary reviews

Rebecca Drew

‘A Fine Novel’ …The Book has quality and treats a limited subject with a largeness of outlook and a lack of the catchpenny emotions that give it distinction. The whole thing is more suggestion than fact. But it is a large suggestion. It rouses. It interests. It touches the imagination (Daily News, see British Newspaper Archive)

Rebecca Drew is a tale of rural English life after the manner, but happily devoid of the offensive qualities of the Hardy school. A petty, gossiping English hamlet; a maiden with some unbeautiful idiosyncrasies, but with a perfect genius for loving, unselfish helpfulness; a stranger who alights on the little community from goodness knows where, and who proves himself a fully nine days’ wonder; an English Church parson of the right sort to whom every villager turns in his time of trouble; … Bessie Spade’s case is haloed round with a golden nimbus noble self-sacrifice- such in brief bald outline are the contents of a remarkably fine story by Edith Dart… the air is sweetly laden with the perfume of the fields and the scented clover … (Dundee Courier, 1910, see British Newspaper Archive)

Likeness

A chance meeting in a picture gallery, in front of a portrait, makes two young women in different spheres of life – a typist and the daughter of a millionaire- acquainted with each other, and with the fact that they are so like that except by dress, no one can distinguish them apart … there are happenings and results. The idea is far from original. But it is followed out with some skill, and worked into a story that keeps the attention rivetted to the close, in a double wedding. (The Scotsman, 5th October 1912, in British Newspaper Archive)

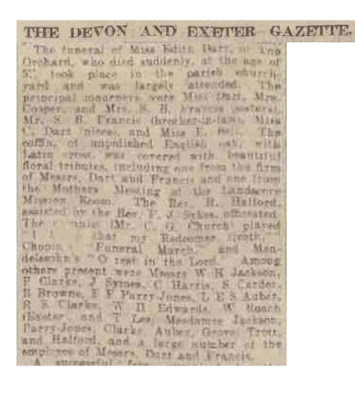

Sareel

Sareel by Edith Dart, is published by Philip Allan and Co, is a very charming Dartmoor story, in the early part of which the vernacular of the moor is freely and accurately used. It has the genuine tone of a first-class romance, and like the well-written story, it undoubtedly is, fixes and maintains the interest of the reader throughout. There is no attempt at anticipating the clever denouement of the love tangle. Its role is emotive, and the sequence of events is unbroken. The last chapters are touching and pathetic and Sareel emerges from her ordeal with the charming simplicity of a tumultuous life, purified, unchastened and unsullied. The farmers wife, narrow in vision, sordid. (The Devon and Exeter Gazette 18 May 1920, in British Newspaper Archive)

See also Remembering Edith Dart, Crediton’s Edwardian Novelist and Poet

Acknowledgments

I’m grateful for the kind assistance given me by staff at Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections & University Archives Northwestern University – especially to Jason Nargis and for his/their kind permission to quote from this file of letters.

I'm also grateful to Emma Farmer, Reading-Room Assistant at The Museum of English Rural Life and University of Reading Special Collections for her help in locating the Reader's Report by Bernard Miall on Tamsin by Edith Dart.

I'm also grateful to staff at Devon Record Office for help with my queries about Edith Dart.

And for help with research about Edith Dart's life I'm especially grateful to Keith Parsons (Researcher Crediton Museum); William (Bill) Jerman (Crediton Church); John Heal (Crediton Museum).

February 4, 2023

Remembering Edith Dart, Crediton’s Edwardian Novelist and Poet; 'As a novelist in “Miriam,” in “Likeness,” in “Rebecca Drew,” and especially in “Sareel,” Devon lives again':

Remembering Edith Dart, Crediton’s Edwardian Novelist and Poet; As a novelist in “Miriam,” in “Likeness,” in “Rebecca Drew,” and especially in “Sareel,” Devon lives again'

(Quotation from Obituary for Edith Dart by Mary Patricia Willcocks)

The Grand Affair

General Buller's Return to Crediton 1900

General Buller's Return to Crediton 1900I am grateful to staff at Crediton Museum for locating the image.

‘Miss Edith Dart, attired in a costume of purple tweed with longer black picture hat presented Lady Audrey Buller with a magnificent shower bouquet with red, white and blue favours’. (The Scotsman 2 November 1900).

General Buller's Return to Crediton 1900

General Buller's Return to Crediton 1900I am grateful to staff at Crediton Museum for locating this image.

As far as I’m aware the vivid depiction in the passage above picturing the young writer and Crediton born woman who, at the time the article from which this quote was written and published in The Scotsman, 2nd November 1900, was about 27, is the only extant description of her. (And it is possible that Edith is in the photo). The passage conjures a vibrant picture, such as, for me, suggests a woman who intends to stand out from the crowd, not someone who prefers seclusion and isolation. For, the occasion about which this feature was written, was by all accounts a grand affair: the return of Crediton’s most renowned hero General Sir Redvers Buller to his home town following a long-standing military career. Buller’s carriage had just come to a standstill outside the railed-off enclosure at Crediton’s then Town Hall steps, bands were striking out 'The Boys of the Old Brigade', and hundreds of local citizens, a thousand children and a detachment of Yeomanry, must have made an arresting greeting-party.

Edith Dart, the young woman who was presenting the bouquet to Buller’s wife, was youngest daughter of one of the town’s leading townsmen, renowned and prosperous builder William Dart:

‘The Dart family is deeply rooted in the soil of Crediton, where her father founded the well-known firm of woodworkers and carvers.’ (From M.P. Willcocks, Appreciation/Obituary for Edith)

Edith was already an author who had short stories and poems published in a variety of contemporary magazines and anthologies. A years later considerable success was to come her way with publication of a poetry collection, Earth with her Bars and Other Poems and several then acclaimed novels, including Miriam, Likeness,and Rebecca Drew, The Loom of Life and Sareel - which was made into a film. You can find and read Sareel and Earth with her Bars on Play Books App. The other books I'm afraid are very hard to come by. There are copies of them at Devon Record Office, but if like me it's not easy to get there, it's a matter of luck finding a old book still in print (and invariably at a great cost) via the internet.

I'll post about Edith's writing in a second post. Here I'm going to concentrate on her life.

Until I came across the account of Buller’s return to Crediton I’d assumed that Edith, who now. in the C21, is just another of the female authors of her time who many years ago disappeared under the cultural radar, had a fragile disposition and perhaps reclusive personality; someone who retired to her attic to pen her books away from the crowd. And for a while when I sent out tentative feelers this assumption was credible because one of the few facts you can glean about Edith - repeated in the few available sources (apparently originally provided by a niece) - is that she was, or at some point became, an invalid, who for many years was virtually immobile in her own room.

I think now that Edith's life story was more subtle and complicated than this…

My interest in Edith is twofold. She's an intriguing novelist/poet whose stories and poems predominantly featured Devon landscapes and people - yet another to add to the list of long forgotten female writers. But also as a keen family historian, when I found that her paternal grandmother’s name twinned that of my own – (though Edith's 'Jane Sampson' was a maiden name and mine my paternal grandmother’s married name), I felt immediately drawn to find more about her; perhaps we met somewhere along her grandmother’s/my grandfather’s family lineages.

Also, whilst browsing various archives and internet sources in search of background information about Edith I’d been staggered to discover that, with a couple of exceptions, including her near neighbour Margaret Pedler, rather than being the only mid-Devon woman who wrote during these early decades of the C20, as initially I believed, Edith Dart was one among a crowd of women from Devon who wrote poetry or and fiction during this era. Many of the women I believe were probably linked with one another through a friendship network. Names of others, some of whom I mentioned in my previous post will I hope one day feature on this blog. I don’t know if Edith knew Margaret Pedler, but she was definitely a close friend of Devon’s ‘forgotten feminist’ writer Mary Patricia Willcocks, who wrote the obituary (quoted from above) for her younger friend following Edith’s death in 1922. I found out about MP Willcocks some years ago. Until some of the other contemporary Devon who wrote begin to receive much more long neglected attention M.P.W., Margaret Pedler and Edith Dart almost stand as sole representatives of a cluster of writers who for the most part have disappeared under the radar, although some of their names are beginning to resurface.

Finding her

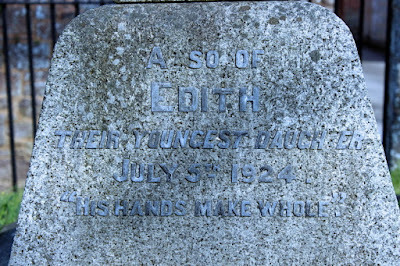

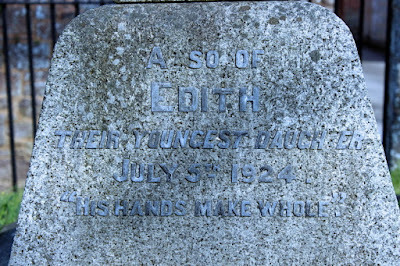

… So who was the once acclaimed Crediton writer Edith Charlotte Maria Dart, whose family were evidently closely linked socially with the town’s then foremost family, the Bullers? Presumably it was the achievements of her father, respected builder whose many projects in and around Crediton brought local attention to the family; especially his notable contributions to Crediton’s church. In 1865, seven years before his youngest daughter was born, William Dart had been appointed carpenter to Crediton church corporation and as such was responsible for much of the church furnishings during that time. (Following William’s death the business was taken over by his son and family and major church improvements continued, including the Buller memorial and a WW1 memorial plaque in the nave). According to a descendant of the Dart family the firm later became called The Ecclesiastical Art Works.

Edith’s paternal ancestral family had deep roots in mid Devon. William’s father John, born in 1792, had married Jane Sampson (born 1788), who was from another intricate family maze, linked with nearby parishes such as South and North Tawton. (I am attempting to follow the Dart Sampson line to see if/when and where they might have connected with our Sampson family).

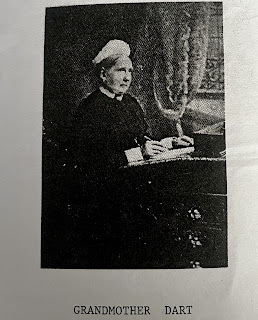

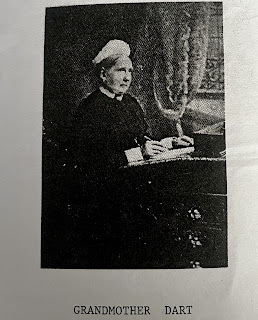

Charlotte, Edith’s mother’s family on the other hand were apparently from Kent. I’ve not yet had too much chance to find out very much about their background, but I wonder if Edith's literary interests in part derived from her mother's side of the family. A pamphlet about the Dart family written by one of the descendants includes a photo of Charlotte at a writing desk, holding a pen.

According to various family history records, born in 1830 in Foots Cray, Kent, Charlotte Elizabeth Mead, one of about seven siblings, was daughter of John Mead, a blacksmith; her mother’s name was Mary (born Mumford), whose ancestors were possibly well-established in the parish. By the time she was 22, in 1851, Charlotte was a servant for a family in Lambeth. Within another four years, in November 1855, far away from Kent and London, she was married and living in Crediton, but I don’t know how, where, or when she met William Dart, Edith’s father. In 1861, the couple with their first two children and William’s widowed mother Jane, were living in Fountain Court in Crediton’s High Street. By 1871, the year before Edith’s birth, the Darts with two more children had moved across the road and were living in a house called Bank Court, which I believe is now 18 High Street. Perhaps Edith, the Dart’s youngest child, was born there, the following year. By the time she was eight, in 1881, the family were living at 128 High Street (near what is now Boots).

128 High Street Crediton showing archway to Dart and Francis.

128 High Street Crediton showing archway to Dart and Francis.Catherine and Alice are named along with Edith, their youngest sibling; the two other children, William, the Dart ‘s son and Frances/Fanny, middle daughter, are not named in the census; perhaps they are married or living elsewhere. William Dart, father and Head of the House is also absent but there are a couple of visitors (Robert Tule and Anne T?) and a servant called Susan Lott.

Just two years later in April 1883 a local tragedy which happened near the town must have severely affected the Dart family. William’s older brother John was killed in a terrible accident whilst out at Kenford Hookway gathering wood for the firm; rolling an elm tree to move it to a timber carriage the chain had broken and John was killed outright by the falling tree.

Now aged eighteen, in 1891 Edith was still at 128 High Street with her father, mother and eldest sister Catherine (Kate). Others in the house the day the census was taken were a sister in law, Frances Mead, Charlotte’s sister, ‘living on her own means’; George Cooper, a grandson, aged three; and a servant called Ada Connall, from nearby Chulmleigh. This house in the middle of Crediton High Street remained the Dart’s home for at least another ten years.

Said to be educated at home (I’m not sure if at the end of the C19 home education was typical for young women of her middle-class status), Edith did attend at least one locally held course and a follow-up examination in 1896, when she was 24. The course in Greek Art and Social Life was held at Exeter Technical College and organised by The University of Cambridge. Edith gained a distinction (Exeter Flying Post, 1 February 1896).

At the time of the next census in 1901 (not long after the celebrations described above commemorating General Buller’s return to his hometown) the eldest and youngest daughters, Catherine and Edith were still with their parents, now both in their late sixties. William, listed as ‘Contractor’ was now 67 and Charlotte two years older; their daughters were 43 and 28. Gerald, another grandson, is also with the family and a different servant, called Anne (Sether?).

During this period of her life (perhaps before she succumbed to the restrictions caused by her heart condition), the young writer was actively involved in a variety of local enterprises. There are glimpses of her comings and goings in contemporary newspapers. In 1895, when she was 23, she may well be the ‘Miss Dart’, one of five local women who applied for the post of Assistant Nurse and/or Industrial Trainer, (Crediton Board of Guardians). In 1899, the year before the occasion I described at the opening of this piece when Crediton welcomed Redvers Buller back to Crediton, she was bridesmaid at a friends’s wedding. In 1902, not long after the class in Exeter, Edith was Treasurer of Crediton’s Packer Fund (a charity organised by the town’s Board of Guardians, who were the overseers for Crediton's Poor Law Union). I haven’t yet had opportunity to find more but I believe she may also have been active with the Crediton suffragette group, one of whose leading figures was Amy Montague, a Crediton woman of Edith's generation who must have known and may have been another of the author's friends.

By the time of the next census, in 1911, everything had changed for the family. Most significantly, Edith’s father had died in 1904, and she, along with her widowed mother and eldest sister, who the family called Kate, had moved north of the High Street into a house called ‘The Orchard’, which I understand had been built by William for his retirement; but sadly that was not to be.

The Orchard Crediton