Julie Sampson's Blog: Writing Women on the Devon Land, page 4

March 1, 2019

Territories of the Mind - an Extract

Landscape of the Mind - Finding Devon's Forgotten Feminist

Pages from M. P. Willcocks, Wings of Desire

Pages from M. P. Willcocks, Wings of Desire

Extract 2 from

Writing Women on the Devon Land

Opening pages from M.P.Willcocks. Mary Queen of Scots

Opening pages from M.P.Willcocks. Mary Queen of Scots

Thanks for reading.

Please follow!

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

Published on March 01, 2019 09:08

February 28, 2019

The Canon - or Not? An Excerpt

'The recognised notion of the literary history of southwest England’s C19/early C20 texts is of a distinctly male lineage, and indeed even now the prevailing view is that the ‘Victorian manuscript of...

[[ This is a content summary only. Visit my website for full links, other content, and more! ]]

[[ This is a content summary only. Visit my website for full links, other content, and more! ]]

Published on February 28, 2019 08:38

The Canon - or Not? An Extract

See Extract 1

The Canon - or Not?

From Writing Women on the Devon Land

Cover of Williamson's Tarka the Otter

Cover of Williamson's Tarka the Otter

Thanks for reading.

Please follow!

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

The Canon - or Not?

From Writing Women on the Devon Land

Cover of Williamson's Tarka the Otter

Cover of Williamson's Tarka the OtterThanks for reading.

Please follow!

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

Published on February 28, 2019 08:38

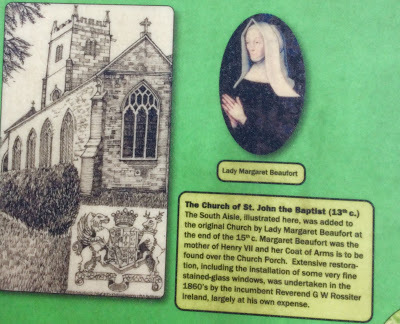

Skipping Qs or Rs, but Spending Time down in Sampford Peverell - Looking for Mid-Devon's Literary Links with a King's Mother

Writing Women on the Devon Land

A – Z of Devon Women Writers & Places

Sampford Peverell Church & Richmond Houseonce home of Margaret BeaufortPhoto Julie Sampson

Sampford Peverell Church & Richmond Houseonce home of Margaret BeaufortPhoto Julie Sampson

Skipping Qs or Rs, but Spending Time down in Sampford Peverell - Looking for Mid-Devon's Literary Links with a King's Mother

For the first time, I'm a little stuck in this A-Z. If anyone out there knows about a link between a woman writer and a Devon parish beginning with Q or R (she should have been living in any period ending 1965 or so - the time period of Writing Women on the Devon Land ), well please do get in touch. She may have lived in the parish, or have written about the place or indeed stayed there at some point. I may have to give up with Q (Queen's Nympton? ) but R might be possible - Rackenford, Romansleigh, Rose-Ash?

Lady Margaret BeaufortUnidentified painter [Public domain]

Lady Margaret BeaufortUnidentified painter [Public domain]

So, given the above comments, I've decided to pass on to S parishes, for which there are many choices. This time round I'm going for Sampford Peverell, whose connections with Henry VII's mother Lady Margaret Beaufort Countess of Richmond and Derby make the village an intriguing place to look at, especially for those who are interested in Devon's lost literary links. Sampford Peverell's Society website has a useful page about Margaret and the village, which notes how she had the old rectory built for her own use.

I posted a short fragment of fiction about Margaret Beaufort Countess of Richmond and Derby on my previous blog Re-Imagining the Queen's Mother some time ago. The piece eventually became part of Matroyshka, a fictional sequence written around various woman who wrote in Devon. This blog also contains Imagining Translation, a short poem based on Margaret's links with Sampford Peverell.

Both poem and fiction fragment were very much based on facts about Lady Beaufort, who is known to have visited and stayed at the village in 1467 (see Sampford Peverell Society).Then, twenty years later in 1487, a couple of years after her son became king, his mother spent time down in Devon again. By now, with popular consent she was called 'My Lady, the King's Mother'.

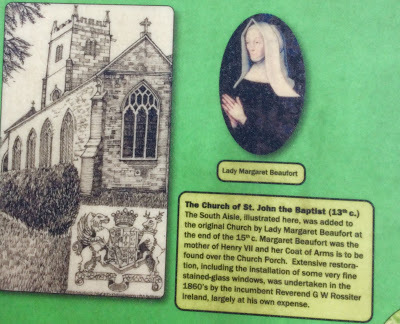

Plaque in Sampford Peverell about Margaret Beaufort and the church During this time, as a keen and avid reader and translator, Margaret may have been reading a then popular chivalric French romance, called Blanchardine and Eglantine.[See note2). She is said to have purchased a copy of the text from Caxton, then commissioned him to print and publish it in the vernacular, which he did, in 1489.

Plaque in Sampford Peverell about Margaret Beaufort and the church During this time, as a keen and avid reader and translator, Margaret may have been reading a then popular chivalric French romance, called Blanchardine and Eglantine.[See note2). She is said to have purchased a copy of the text from Caxton, then commissioned him to print and publish it in the vernacular, which he did, in 1489.

The historical narrative assessment of this important royal woman tends to stress her political involvements, and work as patron of other literary texts, but Margaret Beaufort is an important literary woman in her own right. She's considered by academics to have been 'Renaissance England's first female translator' and/or the 'first English woman in print' (see note1) and her own translations of two religious treatises are now being recognised as significant contributions in their own right to the canon of English literature.

Margaret's contribution to the translated text of Blanchardine and Eglantine was as sponsor and patron of Caxton, but I have wondered if she may have studied the original work in French and perhaps used it as a practice text for her own later translations. Of course it is only in my imagination that she was reading and working on that text when she was down in her Devon manor, but given the dates, it is feasible to picture her in the process of turning over the story in her imagination as a theme for fictional re-invention.

Mother of the man whose ultimate future depended on the outcome of the turbulent events in the autumn of 1483, during one of those especially critical periods, when the outcome of events taking place in the Westcountry would unfold and ultimately impact disastrously on the whole country, Margaret had taken centre-stage, masterminding the whole plot of the western based Buckingham Rebellion against Richard III.The support she gained in 1483 from

Westcountry noble-men may have left her with a soft spot toward the region and its people. Perhaps the manor at Sampford Peverell and its nearby villages (including Uplowman, where Margaret arranged for the building of the church) became a place of refuge for Margaret). Given that she also stayed at one of her other manors along the Devon lanes, at Torrington, Devon seems to have been close to her heart.

Uplowman church

Uplowman church

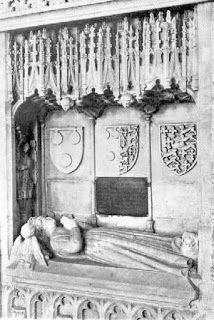

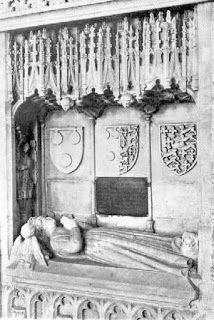

Tomb in Colyton Churchnow thought to be Margaret Beaufort wife of Thomas Courtenay13th Earl of Devon

Tomb in Colyton Churchnow thought to be Margaret Beaufort wife of Thomas Courtenay13th Earl of Devon

The county may also have held a special place for her because many of her ancestors were rooted in the county, although Margaret may not have remembered her aunt of the same name, for she had died when her niece was only 5. (Granddaughter of Edward III, the earlier Margaret Beaufort had married Thomas, 5th Earl of Courtenay during the early upheavals of the Wars of the Roses. An effigy in Colyton church is now thought to be that of Margaret Beaufort Courtenay, Lady Margaret Beaufort's aunt).

As well as her literary pursuits, Beaufort's interest in Devon may have been associated with the turbulent vicissitudes of the pre-eminent Courtenay family, whose main residence at Tiverton castle was less than two miles west along the trackways from Sampford Peverell. In 1467, Edward IV conferred the rich Devon estates of Henry, the latest attainted Courtenay Earl, on Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy, who'd recently been appointed Lord High Treasurer. By November of the same year that the Beaufort couple made their visit to Sampford Peverell, Blount had married, as his second wife, Lady Anne Neville, Duchess of Buckingham, who through her first husband, Humphrey Stafford 1st Duke of Buckingham, became Margaret Beaufort's mother-in-law. Just coincidence maybe. The Staffords' journey and stay in their Sampford Manor during that time was perhaps connected with that of the newly married Blounts, who may have been down in Devon viewing their newly acquired lands. The women had more than their respective lands in common. Like her daughter in law Anne Neville was a book addict and known for her piety and advanced learning. In her will she left Margaret several texts: 'a book of English called Legenda Sanctorum, a book of French, called Luun, another book of French epistles and gospels and a primer with clasps of silver gilt covered with purple velvet'. (See The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women.)

In and not far from the village of Sampford Peverell, there are still sites that in the fifteenth century must have been stand-out places in the landscape, likely to have been places-to-visit by the royal entourage. Just up the hill from Richmond House to the north (near the site of the original village) was the (probable) castle, which had been built just over one hunded years before -

Looking toward possible site of Sampford Peverell castle from the villageIt's not easy to work out which family owned the castle in the late fifteenth century - it having passed through several prestigious locals' hands (including Dinhams/Aisthorpes and Peverells), but given that at this time it was Margaret herself who had inherited the manor from John, Earl of Somerset, I can't help wondering if she may even have stayed there herself. And then there were the nearby religious establishments - the Halberton Augustinian priory (or College) along the track toward Tiverton, at Halberton and the also Augustinian Priory just east at Canonsleigh, which I wrote about in an earlier blog-post The Mystery of the Ancrene Wisse and the Canononnesses at Canonsleigh. I'd love at this blog-point to be able to establish a link between at least one of the prioresses of Canonsleigh and Lady Margaret, who was famed for her charitable deeds, her piety and commitment to daily religious observance, and believe there may be some kind of close connection as yet unrevealed.

Looking toward possible site of Sampford Peverell castle from the villageIt's not easy to work out which family owned the castle in the late fifteenth century - it having passed through several prestigious locals' hands (including Dinhams/Aisthorpes and Peverells), but given that at this time it was Margaret herself who had inherited the manor from John, Earl of Somerset, I can't help wondering if she may even have stayed there herself. And then there were the nearby religious establishments - the Halberton Augustinian priory (or College) along the track toward Tiverton, at Halberton and the also Augustinian Priory just east at Canonsleigh, which I wrote about in an earlier blog-post The Mystery of the Ancrene Wisse and the Canononnesses at Canonsleigh. I'd love at this blog-point to be able to establish a link between at least one of the prioresses of Canonsleigh and Lady Margaret, who was famed for her charitable deeds, her piety and commitment to daily religious observance, and believe there may be some kind of close connection as yet unrevealed.

There are tantalising hints, waiting for someone who can fathom out the necessary archival documents to tease out the lost links. For instance, Margaret's extended royal networks may link to at least two, possibly more, of the abbesses who were prioresses of the abbey which was in Burlescombe only a few miles east of Sampford Peverell. The three prioresses whose time at the priory coincided with the framing period just before and just after Margaret Beaufort's lifetime, were Margaret Beauchamp (1410-49), Joan Arundell (1449-1471) and Alice Parker (1471-1488). Although the only one of these who I am able to identify with certainty is Joan Arundell, each of these names indicate that the prioress concerned probably came from one of the distinctive families who were knitted into the very genealogical fabric of the C15.

Margaret Beauchamp of Canonsleigh may have been the Margaret Beauchamp who is named on some online ancestral sites as daughter of Thomas Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick and Margaret de Ferrers; given this Margaret Beauchamp's estimated birth date, circa 1376, she would have been the correct age to fit that of the prioress and try as I might (although there are several Margaret Beauchamps in this period), as yet I am not able to find any other who fits dates and other life-facts. It is said that this Margaret married a John Dudley and that following his death became a nun. But as yet that is all I am able to find about her, except that she comes from the heart of a well-known C15 female literary network and also hooks into the royal familial network during the Wars of the Roses - all facts which in light of her possible Devon connections and the possibility of literary associates - make her intriguing.

In 1410, one of Margaret Beauchamp's sister in laws, Elizabeth Berkeley (first wife of Richard 13th Earl of Warwick,), ordered a translation of Boethius' De Consolation Philosophie, which was eventually printed in Tavistock, in Devon in 1525. Another of Margaret Beauchamp (the nun's) sister in laws, Richard's second wife Isabel le Despenser, who died in 1439, was also known as a literary patron; she commissioned John Lydgate to write Fifteen Joys of Our Lady. (See The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women). Meanwhile. Elizabeth Despenser's daughter, who was nun Margaret's niece (and incidentally, just to confuse things even more, was one of the other woman also like her aunt, named Margaret Beauchamp), took up her maternal family habit and became literary patron; she is linked with Talbot's Book of Hours and is also said to have commissioned Lydgate's life of Guy of Warwick (See for example, Book Production in the Nobel Household). One of her husband John Talbot's sisters, Anne Talbot, married Hugh Courtenay 4th Earl of Devon; it was their son Thomas who married Lady Margaret Beaufort's aunt of the same name. Through Anne Beauchamp 16th Countess of Warwick, one of the daughters of her brother and his second wife Isabel le Despenser, Margaret Beauchamp, nun was great aunt of Anne Neville, Queen Consort of England, wife of Richard III.

I must repeat that I am not sure about Margaret Beauchamp of Canonsleigh's identity, but wonder if my hunch is correct and she was the nun-daughter of Thomas 12th Earl of Warwick. I hope any history buffs out there seeing this may be able to connect up the missing dots about this woman, who was prioress up until 1449, just after Lady Margaret Beaufort's birth.

The next abbess, Joan Arundell, followed Margaret Beauchamp as prioress of Canonsleigh until her death in 1470/1. An interesting conjunction of events, for this was only three years after it is known that Lady Margaret Beaufort was staying at Sampford Peverell. If the various online ancestral trees are correct, then Joan Arundell was daughter of John Arundell who was Sheriff of Cornwall and Vice Admiral of England under Thomas Beaufort Duke of Exeter - who was Margaret Beaufort's great uncle. In his will of 1433 John Arundell left '20 marks to Joan my daughter at Camalye'.

Although from our contemporary perspective, Joan Arundell is on history's sidelines, during the turbulent years leading up to Henry VII's reign, men in her family and kin were often in the thick of the action. For example, the year before she died, in 1469, Humphrey Stafford, 1st Earl of Devon, one of the richest Westcountry landowners of the time, who was step-son of Joan's nephew John Arundell through Katherine Chideock, the latter's second wife, was executed by a local mob in Bridgwater. Stafford, a Yorkist, was from a cadet branch of the earls of Stafford and may have been in service for his distant cousin, son of Humphrey Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. A couple of years before, Humphrey Earl of Devon had been appointed Keeper of Dartmoor and Constable of Bridgwater Castle and he'd instigated the execution of Henry Courtenay 7th Earl of Devon. Things went badly wrong for him after this during some altercation in one of the skirmishes of the ongoing war. That's when Stafford was put to death. (See details on Luminarium).

Other men in Joan Arundell's close family link up with literary patronage - which suggests that the women of the family were similarly engaged with books, reading and translation. Her great niece Elizabeth Arundell (daughter of John Arundell and his second wife Katherine Chideock, married Giles Daubeney, whose father William Daubeney is said to have requested Caxton to print an early book about Charles the Great. I'm not sure of the year, but presumably as Daubeney died in 1461, this must have been during the time of Joan Arundell's time at the Devon priory. This contact provides a clue that connects to both Canonsleigh prioress and Margaret Beaufort's own literary activities.

Thomasine Arundell, another of Joan Arundell's great nieces, (she was another of John Arundell's daughters by Katherine Chideock, and sister of Elizabeth), married Sir Henry Marney, who was a member of Henry VII's privy council and in Lady Margaret Beaufort's household.

Alice Parker, the third Canonsleigh prioress who took over from Joan Arundell in 1471, is also interesting to consider in light of possible links with Lady Margaret Beaufort. I'm not totally sure of who she was, just like her predecessors she is now on the margins of history, but all the signs are that Alice was one of the Parker family who were Earls of Morley. The Parker/Morley genealogical network is not easy to trace and there are differing accounts of them online. But as far as I am able to make sense so far, Henry Parker, 10th Baron grew up in Margaret Beaufort's household and was known as a translator. He was son of Alice Lovell Parker, 9th Baroness of Morley and William Parker, who was standard bearer to Richard III. Alice's brother Henry Lovell, 8th Baron Morley married Elizabeth de la Pole, who was daughter of Elizabeth Plantaganet. The name Alice recurs through Parker family generations - one of them was Alice Lovell Parker's daughter. However, that is as far as I can get, because the dates as given do not fit that of the Canonsleigh prioress. Possibly Alice at Canonsleigh was one of the daughters from one of the earlier cadet branches, or alternatively, the estimated dates which are provided on the online sites are not correct. Hopefully one day someone will work out who Alice, prioress, was.

I'm wading a little deep here with this cross-section of mid to late C15 aristocracy in terms of their possible literary and social links with the prioresses of Canonsleigh and/or Margaret Beaufort. I do not pretend to have discovered anything important, yet nor have I covered half of the possible networks of connection. It's surely just the tip of a lost literary iceberg. I'm just trying to lay out how, with a little perseverance, the story of Margaret Beaufort and Devon branches out into a welter of literary and historical possibility.

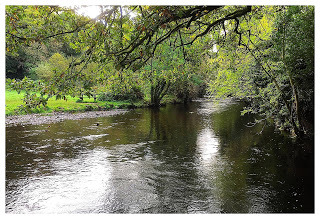

Dedications and inscriptions found on a variety of printed books from this era indicate that books were passed on between sisters, from mothers to daughters or other sororal pairs and between women from extended kinship groups. It's not difficult to re-invent a scene in a shadowed solar chamber high up in the Devon manor house next to the church, where a group of women (along with other female kin) all at the top of the social hierarchy and all closely allied to the royal family, pour over one of their beloved books. The readers might occasionally glance up and out through the window with its tiny criss-crossed glass panes and gaze over the landscape panning out over the low-lying patchworked lands of the Culm valley, with its scrublands and sheep-grazed strip lands. No sign of the canal snaking quietly beneath the trees and through the meadows, where we, now, can step onto the towpath and walk for miles west or east admiring the natural tranquillity of the scene. No sign of the once presence of a woman who's left us with such a rich literary and historical legacy; though hidden in our past, she still surely hovers in the very ether of this place.

Looking toward Sampford Peverell churchfrom the canal.

Looking toward Sampford Peverell churchfrom the canal.

1. PATRICIA DEMERS Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme

Vol. 35, No. 4, Special issue / Numéro spécial : Women's Translations in Early Modern England and France / La traduction au féminin en France et en Angleterre (XVIe et XVIIe siècles) (FALL / AUTOMNE 2012), pp. 45-61

2. Thomas Penn, Winter King: Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England, (Penguin, 2011), 311.

Thanks for reading.

Please follow!

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

A – Z of Devon Women Writers & Places

Sampford Peverell Church & Richmond Houseonce home of Margaret BeaufortPhoto Julie Sampson

Sampford Peverell Church & Richmond Houseonce home of Margaret BeaufortPhoto Julie SampsonSkipping Qs or Rs, but Spending Time down in Sampford Peverell - Looking for Mid-Devon's Literary Links with a King's Mother

For the first time, I'm a little stuck in this A-Z. If anyone out there knows about a link between a woman writer and a Devon parish beginning with Q or R (she should have been living in any period ending 1965 or so - the time period of Writing Women on the Devon Land ), well please do get in touch. She may have lived in the parish, or have written about the place or indeed stayed there at some point. I may have to give up with Q (Queen's Nympton? ) but R might be possible - Rackenford, Romansleigh, Rose-Ash?

Lady Margaret BeaufortUnidentified painter [Public domain]

Lady Margaret BeaufortUnidentified painter [Public domain]So, given the above comments, I've decided to pass on to S parishes, for which there are many choices. This time round I'm going for Sampford Peverell, whose connections with Henry VII's mother Lady Margaret Beaufort Countess of Richmond and Derby make the village an intriguing place to look at, especially for those who are interested in Devon's lost literary links. Sampford Peverell's Society website has a useful page about Margaret and the village, which notes how she had the old rectory built for her own use.

I posted a short fragment of fiction about Margaret Beaufort Countess of Richmond and Derby on my previous blog Re-Imagining the Queen's Mother some time ago. The piece eventually became part of Matroyshka, a fictional sequence written around various woman who wrote in Devon. This blog also contains Imagining Translation, a short poem based on Margaret's links with Sampford Peverell.

Both poem and fiction fragment were very much based on facts about Lady Beaufort, who is known to have visited and stayed at the village in 1467 (see Sampford Peverell Society).Then, twenty years later in 1487, a couple of years after her son became king, his mother spent time down in Devon again. By now, with popular consent she was called 'My Lady, the King's Mother'.

Plaque in Sampford Peverell about Margaret Beaufort and the church During this time, as a keen and avid reader and translator, Margaret may have been reading a then popular chivalric French romance, called Blanchardine and Eglantine.[See note2). She is said to have purchased a copy of the text from Caxton, then commissioned him to print and publish it in the vernacular, which he did, in 1489.

Plaque in Sampford Peverell about Margaret Beaufort and the church During this time, as a keen and avid reader and translator, Margaret may have been reading a then popular chivalric French romance, called Blanchardine and Eglantine.[See note2). She is said to have purchased a copy of the text from Caxton, then commissioned him to print and publish it in the vernacular, which he did, in 1489. The historical narrative assessment of this important royal woman tends to stress her political involvements, and work as patron of other literary texts, but Margaret Beaufort is an important literary woman in her own right. She's considered by academics to have been 'Renaissance England's first female translator' and/or the 'first English woman in print' (see note1) and her own translations of two religious treatises are now being recognised as significant contributions in their own right to the canon of English literature.

Margaret's contribution to the translated text of Blanchardine and Eglantine was as sponsor and patron of Caxton, but I have wondered if she may have studied the original work in French and perhaps used it as a practice text for her own later translations. Of course it is only in my imagination that she was reading and working on that text when she was down in her Devon manor, but given the dates, it is feasible to picture her in the process of turning over the story in her imagination as a theme for fictional re-invention.

Mother of the man whose ultimate future depended on the outcome of the turbulent events in the autumn of 1483, during one of those especially critical periods, when the outcome of events taking place in the Westcountry would unfold and ultimately impact disastrously on the whole country, Margaret had taken centre-stage, masterminding the whole plot of the western based Buckingham Rebellion against Richard III.The support she gained in 1483 from

Westcountry noble-men may have left her with a soft spot toward the region and its people. Perhaps the manor at Sampford Peverell and its nearby villages (including Uplowman, where Margaret arranged for the building of the church) became a place of refuge for Margaret). Given that she also stayed at one of her other manors along the Devon lanes, at Torrington, Devon seems to have been close to her heart.

Uplowman church

Uplowman church

Tomb in Colyton Churchnow thought to be Margaret Beaufort wife of Thomas Courtenay13th Earl of Devon

Tomb in Colyton Churchnow thought to be Margaret Beaufort wife of Thomas Courtenay13th Earl of DevonThe county may also have held a special place for her because many of her ancestors were rooted in the county, although Margaret may not have remembered her aunt of the same name, for she had died when her niece was only 5. (Granddaughter of Edward III, the earlier Margaret Beaufort had married Thomas, 5th Earl of Courtenay during the early upheavals of the Wars of the Roses. An effigy in Colyton church is now thought to be that of Margaret Beaufort Courtenay, Lady Margaret Beaufort's aunt).

As well as her literary pursuits, Beaufort's interest in Devon may have been associated with the turbulent vicissitudes of the pre-eminent Courtenay family, whose main residence at Tiverton castle was less than two miles west along the trackways from Sampford Peverell. In 1467, Edward IV conferred the rich Devon estates of Henry, the latest attainted Courtenay Earl, on Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy, who'd recently been appointed Lord High Treasurer. By November of the same year that the Beaufort couple made their visit to Sampford Peverell, Blount had married, as his second wife, Lady Anne Neville, Duchess of Buckingham, who through her first husband, Humphrey Stafford 1st Duke of Buckingham, became Margaret Beaufort's mother-in-law. Just coincidence maybe. The Staffords' journey and stay in their Sampford Manor during that time was perhaps connected with that of the newly married Blounts, who may have been down in Devon viewing their newly acquired lands. The women had more than their respective lands in common. Like her daughter in law Anne Neville was a book addict and known for her piety and advanced learning. In her will she left Margaret several texts: 'a book of English called Legenda Sanctorum, a book of French, called Luun, another book of French epistles and gospels and a primer with clasps of silver gilt covered with purple velvet'. (See The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women.)

In and not far from the village of Sampford Peverell, there are still sites that in the fifteenth century must have been stand-out places in the landscape, likely to have been places-to-visit by the royal entourage. Just up the hill from Richmond House to the north (near the site of the original village) was the (probable) castle, which had been built just over one hunded years before -

Sampford Peverell had a castle or at least a castellated mansion built about 1337 and referred to as Sampford Castle. Its exact location is unknown but earthworks north of Sampford Barton may be the remains of this structure. There is also some evidence of either a possible moat or fish ponds. (Sampford Peverell Society)

Looking toward possible site of Sampford Peverell castle from the villageIt's not easy to work out which family owned the castle in the late fifteenth century - it having passed through several prestigious locals' hands (including Dinhams/Aisthorpes and Peverells), but given that at this time it was Margaret herself who had inherited the manor from John, Earl of Somerset, I can't help wondering if she may even have stayed there herself. And then there were the nearby religious establishments - the Halberton Augustinian priory (or College) along the track toward Tiverton, at Halberton and the also Augustinian Priory just east at Canonsleigh, which I wrote about in an earlier blog-post The Mystery of the Ancrene Wisse and the Canononnesses at Canonsleigh. I'd love at this blog-point to be able to establish a link between at least one of the prioresses of Canonsleigh and Lady Margaret, who was famed for her charitable deeds, her piety and commitment to daily religious observance, and believe there may be some kind of close connection as yet unrevealed.

Looking toward possible site of Sampford Peverell castle from the villageIt's not easy to work out which family owned the castle in the late fifteenth century - it having passed through several prestigious locals' hands (including Dinhams/Aisthorpes and Peverells), but given that at this time it was Margaret herself who had inherited the manor from John, Earl of Somerset, I can't help wondering if she may even have stayed there herself. And then there were the nearby religious establishments - the Halberton Augustinian priory (or College) along the track toward Tiverton, at Halberton and the also Augustinian Priory just east at Canonsleigh, which I wrote about in an earlier blog-post The Mystery of the Ancrene Wisse and the Canononnesses at Canonsleigh. I'd love at this blog-point to be able to establish a link between at least one of the prioresses of Canonsleigh and Lady Margaret, who was famed for her charitable deeds, her piety and commitment to daily religious observance, and believe there may be some kind of close connection as yet unrevealed. There are tantalising hints, waiting for someone who can fathom out the necessary archival documents to tease out the lost links. For instance, Margaret's extended royal networks may link to at least two, possibly more, of the abbesses who were prioresses of the abbey which was in Burlescombe only a few miles east of Sampford Peverell. The three prioresses whose time at the priory coincided with the framing period just before and just after Margaret Beaufort's lifetime, were Margaret Beauchamp (1410-49), Joan Arundell (1449-1471) and Alice Parker (1471-1488). Although the only one of these who I am able to identify with certainty is Joan Arundell, each of these names indicate that the prioress concerned probably came from one of the distinctive families who were knitted into the very genealogical fabric of the C15.

Margaret Beauchamp of Canonsleigh may have been the Margaret Beauchamp who is named on some online ancestral sites as daughter of Thomas Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick and Margaret de Ferrers; given this Margaret Beauchamp's estimated birth date, circa 1376, she would have been the correct age to fit that of the prioress and try as I might (although there are several Margaret Beauchamps in this period), as yet I am not able to find any other who fits dates and other life-facts. It is said that this Margaret married a John Dudley and that following his death became a nun. But as yet that is all I am able to find about her, except that she comes from the heart of a well-known C15 female literary network and also hooks into the royal familial network during the Wars of the Roses - all facts which in light of her possible Devon connections and the possibility of literary associates - make her intriguing.

In 1410, one of Margaret Beauchamp's sister in laws, Elizabeth Berkeley (first wife of Richard 13th Earl of Warwick,), ordered a translation of Boethius' De Consolation Philosophie, which was eventually printed in Tavistock, in Devon in 1525. Another of Margaret Beauchamp (the nun's) sister in laws, Richard's second wife Isabel le Despenser, who died in 1439, was also known as a literary patron; she commissioned John Lydgate to write Fifteen Joys of Our Lady. (See The Cultural Patronage of Medieval Women). Meanwhile. Elizabeth Despenser's daughter, who was nun Margaret's niece (and incidentally, just to confuse things even more, was one of the other woman also like her aunt, named Margaret Beauchamp), took up her maternal family habit and became literary patron; she is linked with Talbot's Book of Hours and is also said to have commissioned Lydgate's life of Guy of Warwick (See for example, Book Production in the Nobel Household). One of her husband John Talbot's sisters, Anne Talbot, married Hugh Courtenay 4th Earl of Devon; it was their son Thomas who married Lady Margaret Beaufort's aunt of the same name. Through Anne Beauchamp 16th Countess of Warwick, one of the daughters of her brother and his second wife Isabel le Despenser, Margaret Beauchamp, nun was great aunt of Anne Neville, Queen Consort of England, wife of Richard III.

I must repeat that I am not sure about Margaret Beauchamp of Canonsleigh's identity, but wonder if my hunch is correct and she was the nun-daughter of Thomas 12th Earl of Warwick. I hope any history buffs out there seeing this may be able to connect up the missing dots about this woman, who was prioress up until 1449, just after Lady Margaret Beaufort's birth.

The next abbess, Joan Arundell, followed Margaret Beauchamp as prioress of Canonsleigh until her death in 1470/1. An interesting conjunction of events, for this was only three years after it is known that Lady Margaret Beaufort was staying at Sampford Peverell. If the various online ancestral trees are correct, then Joan Arundell was daughter of John Arundell who was Sheriff of Cornwall and Vice Admiral of England under Thomas Beaufort Duke of Exeter - who was Margaret Beaufort's great uncle. In his will of 1433 John Arundell left '20 marks to Joan my daughter at Camalye'.

Although from our contemporary perspective, Joan Arundell is on history's sidelines, during the turbulent years leading up to Henry VII's reign, men in her family and kin were often in the thick of the action. For example, the year before she died, in 1469, Humphrey Stafford, 1st Earl of Devon, one of the richest Westcountry landowners of the time, who was step-son of Joan's nephew John Arundell through Katherine Chideock, the latter's second wife, was executed by a local mob in Bridgwater. Stafford, a Yorkist, was from a cadet branch of the earls of Stafford and may have been in service for his distant cousin, son of Humphrey Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. A couple of years before, Humphrey Earl of Devon had been appointed Keeper of Dartmoor and Constable of Bridgwater Castle and he'd instigated the execution of Henry Courtenay 7th Earl of Devon. Things went badly wrong for him after this during some altercation in one of the skirmishes of the ongoing war. That's when Stafford was put to death. (See details on Luminarium).

Other men in Joan Arundell's close family link up with literary patronage - which suggests that the women of the family were similarly engaged with books, reading and translation. Her great niece Elizabeth Arundell (daughter of John Arundell and his second wife Katherine Chideock, married Giles Daubeney, whose father William Daubeney is said to have requested Caxton to print an early book about Charles the Great. I'm not sure of the year, but presumably as Daubeney died in 1461, this must have been during the time of Joan Arundell's time at the Devon priory. This contact provides a clue that connects to both Canonsleigh prioress and Margaret Beaufort's own literary activities.

Thomasine Arundell, another of Joan Arundell's great nieces, (she was another of John Arundell's daughters by Katherine Chideock, and sister of Elizabeth), married Sir Henry Marney, who was a member of Henry VII's privy council and in Lady Margaret Beaufort's household.

Alice Parker, the third Canonsleigh prioress who took over from Joan Arundell in 1471, is also interesting to consider in light of possible links with Lady Margaret Beaufort. I'm not totally sure of who she was, just like her predecessors she is now on the margins of history, but all the signs are that Alice was one of the Parker family who were Earls of Morley. The Parker/Morley genealogical network is not easy to trace and there are differing accounts of them online. But as far as I am able to make sense so far, Henry Parker, 10th Baron grew up in Margaret Beaufort's household and was known as a translator. He was son of Alice Lovell Parker, 9th Baroness of Morley and William Parker, who was standard bearer to Richard III. Alice's brother Henry Lovell, 8th Baron Morley married Elizabeth de la Pole, who was daughter of Elizabeth Plantaganet. The name Alice recurs through Parker family generations - one of them was Alice Lovell Parker's daughter. However, that is as far as I can get, because the dates as given do not fit that of the Canonsleigh prioress. Possibly Alice at Canonsleigh was one of the daughters from one of the earlier cadet branches, or alternatively, the estimated dates which are provided on the online sites are not correct. Hopefully one day someone will work out who Alice, prioress, was.

I'm wading a little deep here with this cross-section of mid to late C15 aristocracy in terms of their possible literary and social links with the prioresses of Canonsleigh and/or Margaret Beaufort. I do not pretend to have discovered anything important, yet nor have I covered half of the possible networks of connection. It's surely just the tip of a lost literary iceberg. I'm just trying to lay out how, with a little perseverance, the story of Margaret Beaufort and Devon branches out into a welter of literary and historical possibility.

Dedications and inscriptions found on a variety of printed books from this era indicate that books were passed on between sisters, from mothers to daughters or other sororal pairs and between women from extended kinship groups. It's not difficult to re-invent a scene in a shadowed solar chamber high up in the Devon manor house next to the church, where a group of women (along with other female kin) all at the top of the social hierarchy and all closely allied to the royal family, pour over one of their beloved books. The readers might occasionally glance up and out through the window with its tiny criss-crossed glass panes and gaze over the landscape panning out over the low-lying patchworked lands of the Culm valley, with its scrublands and sheep-grazed strip lands. No sign of the canal snaking quietly beneath the trees and through the meadows, where we, now, can step onto the towpath and walk for miles west or east admiring the natural tranquillity of the scene. No sign of the once presence of a woman who's left us with such a rich literary and historical legacy; though hidden in our past, she still surely hovers in the very ether of this place.

Looking toward Sampford Peverell churchfrom the canal.

Looking toward Sampford Peverell churchfrom the canal.1. PATRICIA DEMERS Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme

Vol. 35, No. 4, Special issue / Numéro spécial : Women's Translations in Early Modern England and France / La traduction au féminin en France et en Angleterre (XVIe et XVIIe siècles) (FALL / AUTOMNE 2012), pp. 45-61

2. Thomas Penn, Winter King: Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England, (Penguin, 2011), 311.

Thanks for reading.

Please follow!

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

Published on February 28, 2019 08:17

February 5, 2019

Plymouth's Literary Past in the Writing of its Women

Plymouth Hoe and Smeaton's Tower

Plymouth Hoe and Smeaton's Towercc-by-sa/2.0 - © Ian Capper - geograph.org.uk/p/4651696 A – Z of Devon Women Writers & Places

Plymouth's Literary Past in the Writing of its Women

Early Plymouth Radicals

Yes, I know I could have chosen Paignton, Pinhoe or Princetown as the parish to represent P in this A – Z of Devon’s Women Writers (up to ca. 1965). There’s a cluster of women linked with these places whose lives and writings could be included. But really, it had to be Plymouth. Or, rather, given its important place in Devon’s history and the fact that it is the second largest city in the south-west, Plymouth could not be left out. Over the years (and up until circa 1965) plenty of women writers have lived in or near or written about Plymouth. I’ve already mentioned a few in passing in previous blog posts - see

Frances Gregg, the War and The Mystic Leeway and The Parker Circle of Saltram.

I want to at least acknowledge a handful of others on this A-Z of Devon places associated with women writers of the past.

Back in 1654, having recently traipsed across the rough waterlogged tracks of the wild Devon moors on her way to Cornwall, notorious Fifth Monarchist prophet Anna Trapnel found herself behind bars in a Plymouth prison. Trapnel’s apparent crimes included ‘witchcraft, madness, whoredom, vagrancy, and seditious intent’, all accusations probably manufactured by Cromwell’s henchmen after she’d had the audacity to condemn the Protectorate.

For Trapnel, newly converted visionary who was experiencing frequent and long-lasting trances, the stark moor landscape was a direct sign of God, its idiosyncratic tors ram-full of metaphorical Biblical meaning. Apparently amazed by the ruggedly bleak landscape Trapnel tramped across the moors, remarking later

'that's a far journey indeed … My thoughts were much upon the Rocks I passed by in my journey and the dangerous rocky places I rode over … now I feared not, but was very cheerfully carried on, beholding my rock, Christ, through those emblems of Rocks …The young prophetess was not in the city of Plymouth for long; she was soon hauled out and transported back to jail in London.

At Truro she once again spoke in public (or at least in her lodgings in front of an open window) and began to pray, sing, and go into trances. She again became a centre of popular interest. People came to pull her out of bed and out of her trance, to take her before justices of the peace on suspicion of being a witch. She refused to wake, even when her eyelids were forced open to check on her state of consciousness. Thus arrested for "aspersing the government", she was brought before judges at Plymouth, notably Judge Lobb. She pleaded not guilty on God's express orders. She was interrogated, bound over in recognizances of £300, and sent back from Plymouth to London, still a prisoner.

Trapnel was down in Cornwall again the following year, in 1655. Coincidence maybe, or possibly the notoriety surrounding her preaching and consequent punishment had a spin-off; for in the same year two Plymouth born women were also charged after interrupting their church minister in the middle of a service - purportedly at ‘the steeple house’, at St Andrew’s Church; the women were taken away from the city and plonked into prison up the road, in Exeter. Though like Trapnel this pair became well-known for penning influential religious tracts, unlike her, they were Quakers.

The women were Priscilla Cotton and Mary Cole, who whilst in prison, from October 1655 to sometime in 1656, co-authored a short, passionate and confrontational pamphlet titled To The Priests and People of England (read extracts and about this text at Radical Christian Writings) – which is said to be the first known extended female defence of female preaching. Arguing that inspired women are duty bound to speak and that church ministers are ‘weakwomen’, their text critiques the state Church of England and challenges a wife’s duty to be subservient to both husband and the ‘head’ of church. Cotton also penned and published As I was in the Prison-House, in 1656 and A Briefe Description, 1659 and A Visitation of Love, in 1661. There are various online sources which feature these two women.

Priscilla Cotton was born in Saltash and married a Plymouth Merchant called Arthur Cotton. As far as I can tell no one has yet established the identity of her parents, but after a quick search via Find My Past, it looks as if Priscilla’s maiden name was Martyn and that her marriage to Arthur Cotton (also traceable via Find My PastRecords), took place inPlymouth, on 20 June 1646:Marriage of Priscilla Martyn to Arthur Cole and below birth of their daughter Elizabeth

Mary Cole was the wife of a Plymouth merchant. She may have been Mary Head, who married a Richard Cole in Plymouth in 1643,Record of marriage of Mary Head & Richard Cole see FindMyPast

or/and a relative of Nicholas Cole, who is mentioned in various sources as a distributor of Quaker texts.

Pamphleteering women played an important part in the early Quaker movement and consequently their works are significant in terms of changing and challenging the roles of women both in that sect and in the wider community, during the years of upheaval before and during the Civil War. Because of this, the Quaker women writers have sometimes been labelled as ‘Mothers of Feminism’ (See Print Culture and the Early Quakers).

Plymouth in those mid-century years of the C17 was a popular place for female preaching, imprisonment and subsequent writing. Given the number of women involved and the close dates, it’s possible that there may have been a network of like-minded radical women working in the south-west (and beyond), perhaps crossing the sectarian divides to achieve a common purpose. (See Print Culture). Katherine Martindale’s name sometimes appears along with that of Cole and Cotton as another woman who took part in the insurrection against the priest, in 1655 (See History of Plymouth). The following year, two more women found themselves in jail after speaking aloud after the priest’s sermon:

In 1656, two otherwise obscure Friends, Margaret Killam and Barbara Patison, addressed a “Warning from the Lord to the Teachers and People” of the city of Plymouth, England. (Why didn't the Early Quakers Celebrate Christmas?)

The women’s written protest included ‘a warning to corrupt magistrates who are persecuting the innocent and the just; witness your practices at Exeter prison’ (See The History of Plymouth from the Earliest Period to the Present Time). Some sources note that Killam’s and Pattison’s protest took place in 1655, the same year as Cole and Cotton were in trouble. Pattison and Killam were from the north of the country, but they had travelled down to Plymouth from the north of the country.See Print Culture and The Early Quakers

The tracts written by all these women share common features: they are typically co-authored, collaborative works, rather than single-authored; they are frequently written and issued from prison; they concern similar themes and issues. It’s easy from our own secular age to side-line these women and their works, but it seems to me that Devon – and especially Plymouth – should be proud of these radical literary foremothers, who were not afraid to stand up, speak their minds and in a day when on the whole women did not put pen to paper, make their protests last the test of time.

****

The Three Reynolds Sisters

It was in the second decade of the C18, only sixty years so or after the appearance of the C17 sectarian women’s writings, that three sisters, not-to-be-ignored C18 literary women were born in Plymouth, or to be more precise, in Plympton. A trio of writers of a generically idiosyncratic bag of texts, that would, from the perspective of the C21 all be considered highly unusual texts. One was Elizabeth Reynolds Johnson, Pamphleteer, whose writings could (in some ways) be viewed as successors to those of the earlier protest tract writers. Elizabeth, who some have labelled ‘pious’ and other as ‘literary theorist’, penned a series of pamphlets, including The Explication of the Vision to Ezekiel,1781, but each of these was apparently printed anonymously. There’s a fascinating piece, which includes the story of how (as one of only two women who ever tried) Elizabeth entered her pamphlet ‘The Astronomy and Geography of the Created World, and of course the longitude', into the competition for the search for longitude, at The Elusive Ladies of the Longitude.

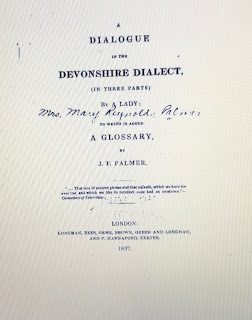

Elizabeth’s older sister Mary Reynolds Palmer’s writing achievements could hardly have been more different from those of her predecessor tract writers, nevertheless Mary wrote at least one text which, though hardly well-known, has not completely disappeared from the literary radar. ‘A Dialogue in the Devonshire Dialect' was once assessed by The Dictionary of National Biography, as the ‘best piece of literature in the vernacular of Devon". The text, written in the form of a play, is an account of the county’s various characters, customs and in particular, the idiosyncratic Devon dialect.From A Dialogue in the Devonshire Dialect

Unfortunately, as has so often happened to many women authors through the centuries, the publishing fate of Dialogue in the Devonshire Dialect was not straightforward; the publication and attribution of authorship to Mary Palmer was not automatic. Although extracts from the text appeared in periodicals during Palmer’s lifetime, the text wasn’t attributed to her and whilst a proportion of Devonshire Dialect did get printed over a century later in 1837, (see images above), even this edition hardly gave credence to its author. It took another two years before a complete edition of the original was published, edited by Palmer’s daughter, Theophila Gwatkin. I'm not yet sure if the copy available via Amazon is this full text.

The youngest writer-sister of the three was Frances Reynolds, who is known more as artist than writer. However, Frances did write, and her Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Taste and the Origins of our Ideasof Beauty &c. has received considerable attention from fashion and cultural theorists. Frances also wrote poems, including A Melancholy Tale, 1790, which according to one source was inspired after 'travelling in a post chaise with a woman she met in Devonshire near the churchyard of Wear near Torrington ...' (see English Female Artists). Frances also kept a Commonplace Book (See Sir Joshua Reynolds; the Painter in Society) and wrote at least one memoir about Samuel Johnson.

None of the sisters appear to have remained in Plymouth. Following marriage to a local solicitor called John Palmer (and Mayor of the town), in 1740, Mary Palmer moved away to GreatTorrington, probably spending the remainder of her life at Palmer House.cc-by-sa/2.0 - © Patricia Barnes - geograph.org.uk/p/2374014

Palmer House

also see The Johnson Society Elizabeth married William Johnson in 1753 (see

But, even if their life-journeys took them away from their home-town, the Reynolds sisters are fascinating to consider in light of their local Plymouth/Plympton connections. Firstly, they were all siblings of their much-more famous artist Joshua Reynolds and it is mostly through him that details of his sisters’ – and their family’s lives - become traceable. Secondly, as I’ve so often found after starting to dig around the archives, the sisters appear to have been participants in a network of contemporary interrelated literary/artistic women.Former Plympton Grammar SchoolFormer Plympton Grammar Schoolwhere the Reynolds' sisters' father was Master

cc-by-sa/2.0 - ©N Chadwick - geograph.org.uk/p/5958100 The sisters’ father was Rev. Samuel Reynolds, Fellow of Balliol College and Master at Plympton Grammar School. Mary born in 1716, was the eldest daughter and third child of eleven children (one source says five or six of them died in infancy). Elizabeth, born in 1721 was a couple of years older than Joshua whilst Frances, born 1729, was apparently the youngest of the siblings.

You can find quite a lot about Samuel via online searches, but information about the Reynolds' mother is elusive. After delving into genealogical websites I was able to piece bits and pieces together. Theophila Potter came from Great Torrington, which presumably explains why several of her children returned there in adult life. However, Theophila's own parentage has been disputed. The best account I’ve come across is that in an old edition of Devon and Cornwall Notes & Queries (1913), which even then, questioned the accepted maternal ancestry of the famed Joshua. Unfortunately, all the hard work that O. A. R. Murry, (the researcher) achieved does not seem to have trickled down the time-line one hundred years later. All the other accounts of the Reynold’s family’s maternal family-tree appear to repeat the genealogy which, true or not, has become part of that family’s legend.

Both Samuel Reynolds and Theophila were said to be religious and scholarly. However, as so often happens with many women who’ve been all but deleted from history, you have to be prepared to do a lot of extra snooping around to find out more than cursory information about the women of the family. Once you start looking at the lives of a mysteriously unknown woman’s father, husband and/or brother/s, and male acquaintance networks, then detective-like, you can soon scoop up all sorts of rich details about the woman/women-in-their-lives. Though virtually air-brushed out of history, if you’re lucky, you can piece her back together, reinvent her. In the case of the trio of Reynolds sisters, you can start to reconcile them, one with the other.

The sisters’ life-journeys and literary accomplishments have more or less been overshadowed by the fame of their brother who happened to end up as the most celebrated English painter of his time. Inevitably, when one’s dipping in and out of the various sources, the references to any one of the women tends to embed at least one rather derogatory judgemental comment. For example, Joshua’s assessment of his sister Frances’ paintings was that ‘they made others laugh and him cry’ (for example, see Joshua Reynolds; the Painter in Society). Ironically perhaps, Mary Elizabeth and Frances Reynolds are best found again through studying their brother’s life and contacts.

Re Mary Palmer, Wikipedia commenting on Joshua, her younger, famous brother, informs us that his eldest sister was:seven years his senior, author of Devonshire Dialogue, whose fondness for drawing is said to have had much influence on him when a boy. In 1740 she provided £60, half of the premium paid to Thomas Hudson the portrait-painter, for Joshua's pupilage, and nine years later advanced money for his expenses in Italy. (Wikipedia)Another source notes that Joshua commented that he had copied drawings of two of his sisters who ‘had a turn for art’. You can find Joshua’s portraits of his sisters and if you look at Plymouth Museum Galleries Archive you can find about the background to the Reynolds family via their postings about Joshua. Frances, the youngest sister (who unlike her sisters did not marry), apparently lived with her brother for many years. She is sometimes referred to as ‘the other Reynolds’, probably because of her closeness to Joshua and also perhaps because (apparently) unlike Mary and Elizabeth, she is directly associated with painting. You’ll more likely find more immediate information about her than her two sisters – probably again, due to her long-time proximity to Joshua.

One enlightening sourcebook I stumbled upon is The Johnson Circle; a Group Portrait, by Lyle Larson, an eye-opener when it comes to establishing the gender family dynamics between the distinguished artist and his three sisters:He treated them with much the same indifference he treated Frances. His behaviour seems all the more strange considering his obligations to them, because they had funded his trip to Italy when he was a young man, so that he could study the Renaissance masters (The Johnson Circle).

Regarding the Reynolds’ sisters’ swirls of social and cultural networks, so far, with an hour or so of internet browsing, I’ve touched upon the following:

Through her husband’s mother, Mary Palmer and her sisters would have been acquainted with Hannah More. Frances painted Hannah's portrait.

Writer Samuel Johnson was in immediate contact with the Reynolds family, as was his companion, the welsh poet Anna Williams.

Poet Elizabeth Carter was probably in the social/literary networks of the Reynold’s family.

The famous ‘Queen of the Blues’ Bluestocking Mrs Elizabeth Montague is said to have been a friend of Frances Reynolds and Frances dedicated her Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Taste and the Origins of our Ideas of Beauty &c. to her. There are a series of letters exchanged between the two women. It is likely perhaps that Frances’ two sisters also participated in meetings and activities of the Bluestockings, one of whose other famous woman members was Fanny Burney, who (because she was a close contact of Mary Palmer’s husband’s mother) is known to have been a visitor at the Reynold’s house in Plymouth, in 1779.

There is a wonderful self-portrait (by Frances Reynolds) of the three Reynolds sisters, which I’d love to reproduce here but for obvious copyright reasons cannot. You can see it on the source listed below In this A-Z I could just as appropriately have included this piece about the Reynolds sisters under T, for Torrington (or G, for Great Torrington), as they all appear to have centred the focus of their lives there, back in the maternal lands of their mother and grandmother, rather than back in Plymouth. However, I felt it better to take them back home, to the place at the heart of their births and textual origins... … And now, resurfacing after immersion in Reynolds' sisters paraphernalia, I am suddenly aware that I've long exceeded the blog-post word limit which blog experts advocate. Oh well, the other Plymouth women writers will need to wait until the next time around ...

[i]Anna Trapnel's Report and Plea: or a Narrative of her Journey from London into Cornwall (1654)

See Hilary Hinds, God's Englishwomen: Seventeenth-century Radical Sectarian Writing and Feminist Criticism (MUP, 1996), 127.[ii] A Blue-Stocking Friendship: The Letters of Elizabeth Montagu and Frances Reynolds in the Princeton Collection. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 41, No. 3 (SPRING 1980), pp. 173-207 (35 pages)[iii] Ibid.

Thanks for reading.

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

Published on February 05, 2019 09:00

August 13, 2018

On the Ways to the Old Literary Roads around Okehampton

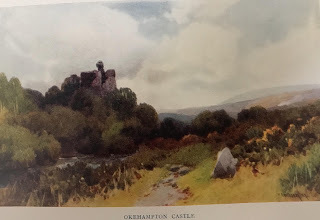

Okehampton Castle

Okehampton CastlePhoto Julie Sampson

Writing Women on the Devon Land

A-Z of Devon Women Writers & Places

On the Ways to the Old Literary Roads around Okehampton

I could have chosen Offwell, Ogwell, Okeford, Otterton, or Ottery St Mary. But for this Alphabet of Devon Women Writers (up to about 1960), I settled on Okehampton. It's partly nostalgia, the town being a favourite place of my childhood, where I (albeit fairly briefly) and before me, both my parents attended school. I don't know of any individual woman author whose home was in the parish up to circa 1960 - but I do know several who included the place in their writings. Rosalind Northcote, Mary Ward and Sophie Dixon all set down in text their personal responses to the scenic, and/or historical characteristic of the Okehampton locality ...

... It is not just the romantic lines of Okehampton castle ruin that call, either when you spot Okehampton castle from the dual carriageway of the A30, or as you negotiate the upward swirls of the road curling up and away from the old town deep in the valley beneath, or through light reflected leaves on the left of the road. It is also the intricate lineage of the genealogical patterning of the past, which suggests that this near empty shell must once have harboured both men and women closely connected to the topmost ruling class, who were likely to be of the then literate fraternity. By the time you see the ruin you have entered the hallowed receptacle of the moor. Before you, are a multitude of enticements.

For me, the northern doorway to Dartmoor's charm has always been the historical marker of this well-known Devon castle. Rosalind Northcote's travelogue/guide-book/historical survey, Devon; its Moorlands, Streams & Coasts (See on Project Gutenberg) outlined the ruin and its vicinity as it appeared in the rustic environment of the early C20.

The castle of Okehampton stands about half a mile from the town and looks on one side over fertile hills and valleys, woods, and rich meadows, and the gleaming waters of the West Okement, on the other towards the bold, changeless outlines of the outer barriers of Dartmoor. The castle was once surrounded by its park ... The Okement rippling over a rocky bed – the name ‘uig maenic’ means the ‘stony water’ – hurries past the foot of a knoll on which the castle rises out of a cloud of green leaves that shelter and half hide the walls. Protected by the river and a steeply scarped bank on the south, a natural ravine on the north and a deep notch cut on the western side, the mass of slate rock that it stands on was a point of vantage.[i]

By West Okement, from where you can see glimpses

By West Okement, from where you can see glimpsesof ruins of Okehampton Castle glinting through the trees.

Old Town Park

Old Town ParkLocal Nature Reserve

Okehampton

There are copies of Northcote's Devon book available from various sites, including Abe Books. I tend to agree with the fairly recent review of the book on the jsbookreader blog. The best feature of Devon; its Moorlands, Streams & Coasts is its inclusion of colour plates of Devon scenes, by acclaimed painter Frederick John Widgery. I feel rather mean saying this about this, but tend to agree with jsbookreader's assessment: Devon; its Moorlands, Streams &Coasts is 'largely built around scraps of learned but much-recycled material'.

Colour Plate of Okehampton Castle, painting by FJ Widgery.

Colour Plate of Okehampton Castle, painting by FJ Widgery.taken from Devon: its Moorlands, Streams & Coasts.

Devon; its Moorlands, Streams & Coasts is a book which anyone who likes to collect Devon history, or landscape books collectors, would love, and ought to have in their library. Of nostalgic value, the text is in the tradition of and influenced by such canonic male-authored Devon books as Crossing's Guide to Dartmoor; but once you get into the mind-set of the time in which it was written,

Devon; its Moorlands, Streams & Coasts does have a certain time-less appeal and Rosalind Northcote's passion for her home county is evident. There are individual touches which the author most likely obtained from personal visits to many of the places she describes.

Daughter of Walter Stafford Northcote, Second Earl of Iddesleigh, Lady Rosalind Northcote wasn't the only author in her family. I'm not sure whether she had any literary female relations, but both her father and her brother Stafford Harry Northcote, Viscount St Cyres also wrote and published books, whilst her grandfather, Stafford Northcote First Earl of Iddesleigh, also had literary interests. For centuries, the Northcote family seat was at Pynes House near Exeter, which, though nowadays known as Devon's Downton Abbey and popular as a local wedding venue, is also known locally for its apparent close association with Jane Austin:

'The second Earl, Walter Stafford Northcote, was a huge admirer of the literary talent of Jane Austen and believed most fervently that his house was indeed the inspiration for Barton Park in Austen’s iconic work, Sense and Sensibility. This tale is still told in the local area and remains as popular as ever' (Pynes House Website)

I'm not saying the information isn't out there in the archives, but in the limited time I've been able to devote to researching Rosalind Northcote I've not found much about her life; maybe someone out there does know about her, or has come across documentation about her in a record office somewhere. The Pynes archives at A2A certainly seems promising. There are a couple of tantalising snippets dotted round the web. One concerns Lady Rosalind's next youngest sister, Lady Elizabeth Northcote, who in 1914 married Sir Randolph Bruce in a celebrated wedding held at Pynes. According to one source, there had initially been plans for Bruce to marry author Rosalind, eldest daughter, but she was found 'prickly' and 'unapproachable' (see Lady Windemere) Elizabeth was 38 at the time of her marriage, quite old for her generation. There are various easily accessible online accounts about this couple; a year after their marriage they travelled to Paris with Rosalind, which suggests the two sisters were probably close. The same description notes that unlike her sister (!) Elizabeth had a 'sweet disposition' and 'was very thoughtful of others' (Lady Windemere). Sadly, Elizabeth died within a year of her marriage, probably of appendicitis.

Lady Rosalind survived her other siblings and died at Pynes in 1950. A visitor to Pynes during her last years is said to have commented: 'She was a law unto herself quite a formidable woman. She used to spend most of her day in a large sitting room with the windows open, chain smoking.' (Lady Windemere).

The National Portrait Gallery has a portrait of Lady Rosalind here.www.columbiavalleypioneer.com/news/the-lady-of-lake-windermere/ ....

But, at this point, though it is tempting to stray further I must not wander away too far from Okehampton, the subject of this blog piece. One hundred years before Northcote's Devon book another local Devon author wrote about Okehampton castle and its surroundings. Sophie Dixon's C19 journals provide us with another detailed panning shot of the castle and its vicinity in an even more pastoral, pre-technologically dominated landscape than that about which Northcote wrote.

Pages from Sophie Dixon's Journal

Pages from Sophie Dixon's Journal which mention Okehampton,

1830 I get the feeling that unlike Rosalind Northcote , Sophie Dixon had more first hand acquaintance with the places she wrote about. You'll find Dixon's name pops up readily in Google searches, especially linked to various descriptions and accounts of Dartmoor. For instance:

Contemporary writers often refer to Dixon, probably because her writing is striking in its detail and immediacy. In his Garden History of Devon Todd Gray notes that she was 'decisive in her writing'. Along, with Anna Eliza Bray and Rachel Evans , two other contemporary female author/travellers whose homes were in the vicinity of Tavistock, Dixon contributed to the C19 discourse of Dartmoor discovery.

For sometime Dartmoor was the home of Miss Sophie Dixon, the charming writer, and her acquaintance with it was extensive. She was in the habit of taking long rambles, setting forth at an early hour, and covering as much ground in a day as many would do in three. Sometimes when on a pedestrian tour she would rise at midnight, and start on her journey soon after, in order to avoid walking under a burning summer sun (Quoted in William Crossing's One Hundred Years on Dartmoor).

In her book Ten days excursion on the western and northern borders of Dartmoor , you can still sense the immediacy of the rapturous, pseudo-pioneering mode of discovery experienced and then voiced by Dixon after she crosses the C19 wild Dartmoor reaches, in 1830:

… we passed near the source of the Lyd, and then altering the direction of our steps the Sourton Tors rose before us, until again diverging to the right we came in view of the West Okement, winding amid a rocky channel, below a descent almost precipitous ... The valley inclining almost to a ravine, the river enters by a winding channel at the foot of Black Tor, which closes the view in a southerly direction. An extensive range of hill, dark with heath, occupies the opposite side of the valley, while a third mountain meets it below.’

... Following a trip to the locality of Fatherford I scribbled a short piece reflecting simultaneously on my own visit and what I re-imagined of Sophie Dixon's ...

If you're lucky ... on moor's northen slopes, at the, just, still, tranquil site of Fatherford, just east of Okehampton and on the edgelands of the multiplying, mushrooming new housing estates, you can reflect and muse beside west Okement’s mirror river, where the wooden bridge crosses over into the glade the other side, where water’s lyrics, a ‘voice of waves’, will lull you to the beguiling wild haunts that writer Sophie Dixon intuited a hundred or so years ago ... Royal ferns flutter at our feet, taking us, slowly, surely, into their green and empty world, beyond glittering light.

Sophie knew she felt, she heard, here, where road and river dissect, where dual worlds seem to briefly meet and part, here, where one looks (and moves us to loop unhurriedly, like snails snaking the undergrowth at our feet), back to the past and the other hurtles us onto the future, which can’t wait; this conveyor belt of concrete we cannot get escape.

As you leave the glade, spin around to catch a glimpse of your past, and hers, before a covey of orange monbretias in the hedge by the stream flare a signal, we are still here, still here, here, here, find us. Us ...

Sophie Dixon also wrote poetry. Her Castalian Hours is made up of a sequence of poems; its title poem Stanzas Written on Dartmoor revels in the wildness and solitude of Longaford, and the surrounding moorland. It's with pseudo-Wordsworthian delight that she captures the scenic grandeur of moor's romantic enticements

And these are yours oh Mountains, these aroundWilliam Crossing praised Dixon’s poems in his Dartmoor travelogue ' Amidst Devonia's Alps' but nowadays, like Rachel Evans and Anna Eliza Bray, although versions of her books are still obtainable, unlike that of their male equivalents, Crossing and Carrington, these women’s published writings are not generally recognised or acclaimed as being significant Dartmoor texts. This is a shame, for between them the trio of C19 Tavistock women fully documented a kaleidoscope of Dartmoor’s richly diverse data. There are, I believe, as yet unexplored interconnections between the three women, Bray, Dixon and Evans, linking both their lives and their texts. All three left a rich legacy of documents, which are testaments to the moor’s unique contribution to Devon’s landscape and heritage and are also encyclopedic in their value to the researcher. If a researcher wants to know something about someone or somewhere concerning Dartmoor’s history, then the likelihood is that they will eventually find the answer in one of the texts of Bray, Dixon or Evans ...

Your time-bleached summits, mingle in the air

A potent voice, a passion stirring sound ...

... I'm asking myself, am I straying again from the ostensible main theme of this blog-piece? I hope not. I don't think so. Okehampton is very much enclosed within, or in the dip of the wrap-around protective landscape cloak, so the Dartmoor-linked comments about the women authors I've so far discussed are relevant ...

... Some fifty years or so before Dixon's journal was published, in 1807, in her collection Original Poems, a Devon poet called Mary Ward evoked the ruin in a poem titled ' Oakhampton Castle '. Albeit rather laboured in tone, Ward's poem's darkly laboured iambic lines project an appropriate mood of Gothic splendour:

stupendous pile whose mouldering towers/declare the wide uncultured day/when thou couldst boast terrific powers/that sought to make the world obey.Ironically, the considerable historical significance of such an ancient skeletal and now ruined building as Okehampton Castle is emphasised because of the poet's use of overly ornate language. The style may be ornate, as well as foreign to contemporary ears, but the underlying message is authentic and eternal. Such an edifice, sunk into the foundations of solid earth within our land was – and is – forever replete with the stories of those who lived before. Nevertheless, Ward’s poem about the once striking and significant castle makes its own original contribution to the maintenance of the site’s importance in public memory. 'Oakhampton Castle's' flourish of romantic ornamentation can help to preserve reflecting fragments of history as they are wrapped within the sparse shell of a ruined building in the landscape. The poem aims to mirror the reality of what was.

However, other than her poems in the collection Original Poems, little seems to be known about the poet herself. Mary Ward herself is elusive and attempts to discover anything substantial about her have proved well-nigh fruitless: she is said to have come from Brixham ; she dedicated her book to the Countess of Loudon (who might be this Flora Campbell); she was an acquaintance of the owner of Raithby Hall, in Leicestershire, Robert Carr Brackbenbury, who rather intriguingly, was also known as a poet. Yet, that is all I have found... If there is anyone out there who knows anything about this elusive C19 poet, please get in touch, so I can add more information about her ...

... Before I leave the lanes and literary losts of Okehampton I'll just mention I've included a short fragment of fiction based on an imagined scenario at Okehampton castle in Part Two of the as yet unpublished Writing Women on the Devon Land . It's based on Hawisia ... a real noblewoman of the C12, whose ancestors from Okehampton were closely connected to the Norman/Plantaganet royal court. Following a lot of detailed and genealogical research, it occurred to me that this Hawisia may well have known the mysterious C12 poet Marie de France . .. 'Someone, who in the mind's interior depths, heard a whisper from that long-ago past, telling me that yes indeed, she was Marie and not to leave her (and her circle of kin including Hawisia) out, from my own reinvented (or as I now see it, reinventing) story' ...

Here's a little taster from the opening of the fictional fragment:

Okehampton Castle’s ruins lie like an abandoned fairy-tale in a hollow on a spur of shale between two rivers flowing beneath Dartmoor.

There’s a deep ditch between it and the country around. Outside the still quite massive wall of the castle, above the curling west Okement river, lie the immense lands of the Chase - the hunting-park of the medieval Courtenay family - which once sprawled its green-throw beneath the splatterings of C20/21 edifices. There’s the army camp, the relatively recently constructed A30, the golf-course, various other houses and paraphernalia ...

Thanks for reading.

© Julie Sampson 2017 All Rights Reserved

Published on August 13, 2018 10:13

June 13, 2018

Noting the Ns in North Tawton

Writing Women on the Devon Land A-Z of Devon Women Writers & Places Noting the Ns in North Tawton

View from beside river Taw

View from beside river Tawat North Tawton

toward Cosdon

Photo Julie Sampson

North Tawton, my Devon parish of choice for 'N' in this alphabet, will often feature on this blog. You will already find the parish mentioned in its introductory pages and at least one other post. This small central Devon town, the place of my childhood years, is anchor for my book about Devon's women writers. It has to be the parish of choice for this A-Z, although I could have picked out several other 'Norths', such as North Molton, North Lew or North Bovey, or other N's, such as Newton Abbot, Newton St Cyres ... For this letter, unlike some, I was spoilt for choice.

Sadly, during the last few weeks, when I have been reflecting on this blog piece, a prominent member of the contemporary North Tawton community has passed away. I want therefore firstly to join in the tributes to Dr JeanShields, an acquaintance, a family friend of my late parents and of my uncle, whose invaluable, painstaking and rigorous research and writing about local history over a period of many years has provided the community with a wealth of invaluable historical material relating to North Tawton and beyond to many other Devon places. Amongst many other achievements - including those attained in her other medical personal - Dr Shields co-edited The Book of North Tawton, a rich resource for anyone who has connections to the parish, or indeed is researching its past. Many times since I've started to research for my book on Devon women writers, when looking up information about the parish and its history, but stumbling on a block, I've turned to the book shelves for The Book ofNorth Tawton. Invariably, a fact, a new or overlooked detail will surface somewhere and I'll be off again. Down a new track of discovery. Some of the information which I'll use in this piece emerged in this way.

Dr Jean Shields, North Tawton's, local history researcher/writer will be sorely missed ...