Tom Stafford's Blog, page 44

November 16, 2013

With every language, a personality?

The Medieval Emperor Charlemagne famously said that “to have another language is to possess a second soul” but the idea that we express different personality traits when we speak another language has usually been left as anecdote.

The Medieval Emperor Charlemagne famously said that “to have another language is to possess a second soul” but the idea that we express different personality traits when we speak another language has usually been left as anecdote.

But The Economist takes this a step further and examines the science behind this idea – which may have more weight than we might first think.

It looks at the issue from lots of intriguing angles. Perhaps the most obvious is that bilingual speakers may have different associations with each language – for example, home and work – and so come to associate different sorts of social behaviours with each.

One of the most interesting is how different language structures might allow for different behaviours, although a grammatical explanation for why the Greeks having a tendency to interrupt during conversation is given short shrift

Is there something intrinsic to the Greek language that encourages Greeks to interrupt?…

In this case, Ms Chalari, a scholar, at least proposed a specific and plausible line of causation from grammar to personality: in Greek, the verb comes first, and it carries a lot of information, hence easy interrupting. The problem is that many unrelated languages all around the world put the verb at the beginning of sentences. Many languages all around the world are heavily inflected, encoding lots of information in verbs. It would be a striking finding if all of these unrelated languages had speakers more prone to interrupting each other. Welsh, for example, is also both verb-first and about as heavily inflected as Greek, but the Welsh are not known as pushy conversationalists.

There’s plenty more interesting analysis in the Economist article and it turns out the magazine’s language blog, called Johnson (relax Americans, it’s a reference to Samuel Johnson) is very good as a whole.

Link to ‘Do different languages confer different personalities?’

November 9, 2013

Look before you tweak: a history of amphetamine

I’ve just found a fascinating article in the American Journal of Public Health on ‘America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic’ and how it compares to the current boom in meth and Ritalin use.

The first amphetamine epidemic ran from 1929–1971 and was largely based on easily available over-the-counter speed in the form of ‘pep pills’, widely abused decongestant inhalers and amphetamine-based ‘anti-depressants’.

The idea of giving speed to depressed people seems quite amazing now, especially considering its tendency to cause anxiety, addition and psychosis in the doses prescribed at the time, but it was widely promoted for this purpose.

The following is a 1945 advert for Benzedrine showing a gentleman who has just been treated for depression and is now a proud and dynamic member of society. Thanks pharmaceutical grade crank!

As an aside, when patients complained about the agitation associated with amphetamine treatment, the drug companies brought out new medications which were speed mixed with barbituates, a class of sedatives.

Not mentioned by the article is the fact that one particular brand of this upper-downer mix called Dexamyl has had a remarkable effect on history – but you’ll have to check the Wikipedia page for the details.

As it happens America is in the midst of another phase of massive stimulant popularity – in the form of street methamphetamine and prescribed Ritalin. In fact, use is at virtually the same levels as when you could buy speed over-the-counter.

By the way, the author of the article also wrote the excellent book On Speed if you want a more in-depth look at the history of the drug.

Link to article in American Journal of Public Health (via @medskep)

2013-11-09 Spike activity

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

The worst neurobollocks infographics on the web – found by the neurobollocks blog.

The symptoms of cyberchondria. Only Human covers an interesting study on online hyperchondria.

The Chicago Reader has a profile of razor-sharp psychologist and voice-hearer Nev Jones.

The trials and benefits of bringing up a bilingual baby in The Economist.

USA Today has an excellent piece on how elite troops who are hyper-adjusted to combat re-adjust to civilian life.

The excellent Providentia blog has an interesting historical piece on babies born in the then Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

Popping the hood on synaesthesia – what’s going on in there? Interesting piece on the neuroscience of synaesthesia from Wiring the Brain.

The Guardian reports on the luxury-stay addiction rehab industry in Malibu.

BREAKING – Psychologist has opinion: Atheism caused by externalised rage at ‘defective father’ according to new psychoanalytic theory of not believing in Gods reported by Religion News Service.

November 8, 2013

How muggers size up your walk

The way people move can influence the likelihood of an attack by a stranger. The good news, though, is that altering this can reduce the chances of being targeted.

How you move gives a lot away. Maybe too much, if the wrong person is watching. We think, for instance, that the way people walk can influence the likelihood of an attack by a stranger. But we also think that their walking style can be altered to reduce the chances of being targeted.

A small number of criminals commit most of the crimes, and the crimes they commit are spread unevenly over the population: some unfortunate individuals seem to be picked out repeatedly by those intent on violent assault. Back in the 1980s, two psychologists from New York, Betty Grayson and Morris Stein, set out to find out what criminals look for in potential victims. They filmed short clips of members of the public walking along New York’s streets, and then took those clips to a large East Coast prison. They showed the tapes to 53 violent inmates with convictions for crimes on strangers, ranging from assault to murder, and asked them how easy each person would be to attack.

The prisoners made very different judgements about these notional victims. Some were consistently rated as easier to attack, as an “easy rip-off”. There were some expected differences, in that women were rated as easier to attack than men, on average, and older people as easier targets than the young. But even among those you’d expect to be least easy to assault, the subgroup of young men, there were some individuals who over half the prisoners rated at the top end of the “ease of assault” scale (a 1, 2 or 3, on the 10 point scale).

The researchers then asked professional dancers to analyse the clips using a system called Laban movement analysis – a system used by dancers, actors and others to describe and record human movement in detail. They rated the movements of people identified as victims as subtly less coordinated than those of non-victims.

Although Professors Grayson and Stein identified movement as the critical variable in criminals’ predatory decisions, their study had the obvious flaw that their films contained lots of other potentially relevant information: the clothes the people wore, for example, or the way they held their heads. Two decades later, a research group led by Lucy Johnston of the University of Canterbury, in New Zealand, performed a more robust test of the idea.

The group used a technique called the point light walker. This is a video recording of a person made by attaching lights or reflective markers to their joints while they wear a black body suit. When played back you can see pure movement shown in the way their joints move, without being able to see any of their features or even the limbs that connect their joints.

Research with point light walkers has shown that we can read characteristics from joint motion, such as gender or mood. This makes sense, if you think for a moment of times you’ve recognised a person from a distance, long before you were able to make out their face. Using this technique, the researchers showed that even when all other information was removed, some individuals still get picked out as more likely to be victims of assault than others, meaning these judgements must be based on how they move.

Walk this way

But the most impressive part of Johnston’s investigations came next, when she asked whether it was possible to change the way we walk so as to appear less vulnerable. A first group of volunteers were filmed walking before and after doing a short self defence course. Using the point-light technique, their walking styles were rated by volunteers (not prisoners) for vulnerability. Perhaps surprisingly, the self-defence training didn’t affect the walkers’ ratings.

In a second experiment, recruits were given training in how to walk, specifically focusing on the aspects which the researchers knew affected how vulnerable they appeared: factors affecting the synchrony and energy of their movement. This led to a significant drop in all the recruits’ vulnerability ratings, which was still in place when they were re-tested a month later.

There is school of thought that the brain only exists to control movement. So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that how we move can give a lot away. It’s also not surprising that other people are able to read our movements, whether it is in judging whether we will win a music competition, or whether we are bluffing at poker. You see how someone moves before you can see their expression, hear what they are saying or smell them. Movements are the first signs of others’ thoughts, so we’ve evolved to be good (and quick) at reading them.

The point light walker research a great example of a research journey that goes from a statistical observation, through street-level investigations and the use of complex lab techniques, and then applies the hard won knowledge for good: showing how the vulnerable can take steps to reduce their appearance of vulnerability.

My BBC Future column from Tuesday. The original is here. Thanks to Lucy Johnston for answering some of my queries. Sadly, and suprisingly to me, she’s no longer pursuing this line of research.

November 5, 2013

A multitude of PTSDs

A new paper in Perspectives in Psychological Science looked at all the possible combinations of symptoms that could achieve a DSM-5 diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder and found there are now 636,120 ways to have PTSD.

This shows one of the many drawbacks of having a ‘check-list’ approach to classifying mental disorder.

636,120 Ways to Have Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Perspectives in Psychological Science

November 2013 vol. 8 no. 6 651-662

Isaac R. Galatzer-Levy

Richard A. Bryant

In an attempt to capture the variety of symptoms that emerge following traumatic stress, the revision of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) criteria in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) has expanded to include additional symptom presentations. One consequence of this expansion is that it increases the amorphous nature of the classification. Using a binomial equation to elucidate possible symptom combinations, we demonstrate that the DSM–IV criteria listed for PTSD have a high level of symptom profile heterogeneity (79,794 combinations); the changes result in an eightfold expansion in the DSM–5, to 636,120 combinations. In this article, we use the example of PTSD to discuss the limitations of DSM-based diagnostic entities for classification in research by elucidating inherent flaws that are either specific artifacts from the history of the DSM or intrinsic to the underlying logic of the DSM’s method of classification. We discuss new directions in research that can provide better information regarding both clinical and nonclinical behavioral heterogeneity in response to potentially traumatic and common stressful life events. These empirical alternatives to an a priori classification system hold promise for answering questions about why diversity occurs in response to stressors.

Many argue that psychiatric diagnoses are mostly just descriptions of syndromes: groups of signs and symptoms that tend to group together rather than the result of a single underlying disorder.

Sometimes they are better thought of a convenient classifications for testing treatments against.

When diagnoses are developed, however, there is always the temptation to continually tweak the definition to allow the inclusion or exclusion of different experiences as valid targets for treatment.

These changes are usually well-intentioned but can lead to unintended consequences – as this study shows.

Link to locked paper from Perspectives in Psychological Science.

November 3, 2013

Hofstadter’s digital thoughts

The Atlantic has an amazing in-depth article on how Douglas Hofstadter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Gödel, Escher, Bach, has been quietly working in the background of artificial intelligence on the deep problems of the mind.

The Atlantic has an amazing in-depth article on how Douglas Hofstadter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Gödel, Escher, Bach, has been quietly working in the background of artificial intelligence on the deep problems of the mind.

Hofstadter’s vision of AI – as something that could help us understand the mind rather than just a way of solving difficult problems – has gone through a long period of being deeply unfashionable.

Developments in technology and statistics have allowed surprising numbers of problems to be solved by sifting huge amounts of data through relatively simple algorithms – something called machine learning.

Translation software, for example, long ago stopped trying to model language and instead just generates output from statistical associations. As you probably know from Google Translate, it’s surprisingly effective.

The Atlantic article tackles Hofstadter’s belief that, contrary to the machine learning approach, developing AI programmes can be a way of testing out ideas about the components of thought itself. This idea may be now starting to re-emerge.

The piece is also works as a sweeping look at the history of AI and the only thing I was left wondering was what Hofstadter makes of the deep learning approach which is a cross between machine learning stats and neurocognitively-inspired architecture.

It’s a satisfying thought-provoking read that rewards time and attention.

If you want another excellent, in-depth read on AI, a great complement is another Atlantic article from last year where Noam Chomsky is interviewed on ‘where artificial intelligence went wrong’.

Both will tell you as much about the human mind as they do about AI.

Link to ‘The Man Who Would Teach Machines to Think’ on Hofstadter.

Link to ‘Noam Chomsky on Where Artificial Intelligence Went Wrong’.

November 2, 2013

2013-11-01 Spike activity

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Alcohol, Sleep, and Why You Might Re-think that Nightcap. Gaines, On Brains on why booze isn’t the best sleep promoter.

The Verge reports on the shocking state of evidence in disaster response psychology.

A neuroscience study on a patient in a coma-like vegetative state indicates he is probably paying attention to sounds – reports BBC News.

The Guardian reports that babies remember melodies heard in the womb according to a new study.

What does it feel like to hold a human brain in your hands? A beautiful piece on Oscillatory Thoughts.

Rethinking the adolescent brain. Neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore talks to The Lancet.

BPS Research Digest covers a study on the ‘cheater’s high‘.

A new psychology paper has found that, ethically, we get worn down over the course of a day. Interesting take from Science 2.0.

mind splutter has a brilliant piece: Time Out Of Mind: A linguistic analysis of 50 years of Bob Dylan lyrics.

This week’s edition of Science is a neuroscience special – all locked sadly – but with a free podcast.

November 1, 2013

My punitive superego is lighting up my brain

This sentence actually appeared in the British Journal of Psychiatry:

This sentence actually appeared in the British Journal of Psychiatry:

Carhart-Harris et al’s finding of activation of Cg25 region of the cingulate gyrus in profound depression is consistent with the idea of an interpersonally isolated and punitive superego desperately trying to prevent overwhelming Pankseppian modalities impulses of panic and rage from reaching consciousness.

Find that in a dead salmon neuroscience haters!

This curious interpretation appeared in a letter in the BJP arguing for how neuroscience supports Freudian psychology.

Link to letter in the BJP.

October 31, 2013

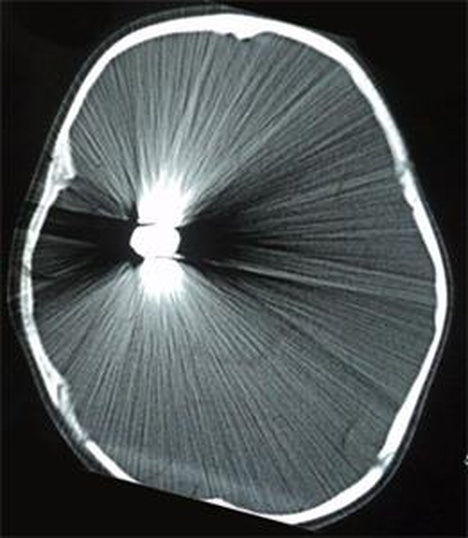

A buried artefact

Sometimes there is an accidental beauty in the most macabre of events. Having a bullet lodged in your brain can produce beautiful CT scans due to the scanner’s difficulty with imaging metal objects.

The scan is from an 8-year-old girl who was hit by a bullet that was fired into the air in celebration. She was reportedly fine but this scan is from her hospital admission.

This pattern is an unintended consequence. It’s called a ‘streak’ or ‘star’ artefact and is caused by a combination of the CT scanner beam being over-absorbed by the dense metal object and the image construction software not being able to make sense of the incoming information correctly.

There’s various other images online if you want more unintended brain glitter.

October 29, 2013

Does studying economics make you more selfish?

When economics students learn about what makes fellow humans tick it affects the way they treat others. Not necessarily in a good way, as Tom Stafford explains.

Studying human behaviour can be like a dog trying to catch its own tail. As we learn more about ourselves, our new beliefs change how we behave. Research on economics students showed this in action: textbooks describing facts and theories about human behaviour can affect the people studying them.

Economic models are often based on an imaginary character called the rational actor, who, with no messy and complex inner world, relentlessly pursues a set of desires ranked according to the costs and benefits. Rational actors help create simple models of economies and societies. According to rational choice theory, some of the predictions governing these hypothetical worlds are common sense: people should prefer more to less, firms should only do things that make a profit and, if the price is right, you should be prepared to give up anything you own.

Another tool used to help us understand our motivations and actions is game theory, which examines how you make choices when their outcomes are affected by the choices of others. To determine which of a number of options to go for, you need a theory about what the other person will do (and your theory needs to encompass the other person’s theory about what you will do, and so on). Rational actor theory says other players in the game all want the best outcome for themselves, and that they will assume the same about you.

The most famous game in game theory is the “prisoner’s dilemma”, in which you are one of a pair of criminals arrested and held in separate cells. The police make you this offer: you can inform on your partner, in which case you either get off scot free (if your partner keeps quiet), or you both get a few years in prison (if he informs on you too). Alternatively you can keep quiet, in which case you either get a few years (if your partner also keeps quiet), or you get a long sentence (if he informs on you, leading to him getting off scot free). Your partner, of course, faces exactly the same choice.

If you’re a rational actor, it’s an easy decision. You should inform on your partner in crime because if he keeps quiet, you go free, and if he informs on you, both of you go to prison, but the sentence will be either the same length or shorter than if you keep quiet.

Weirdly, and thankfully, this isn’t what happens if you ask real people to play the prisoner’s dilemma. Around the world, in most societies, most people maintain the criminals’ pact of silence. The exceptions who opt to act solely in their own interests are known in economics as “free riders” – individuals who take benefits without paying costs.

Self(ish)-selecting group

The prisoner’s dilemma is a theoretical tool, but there are plenty of parallel choices – and free riders – in the real world. People who are always late for appointments with others don’t have to hurry or wait for others. Some use roads and hospitals without paying their taxes. There are lots of interesting reasons why most of us turn up on time and don’t avoid paying taxes, even though these might be the selfish “rational” choices according to most economic models.

Crucially, rational actor theory appears more useful for predicting the actions of certain groups of people. One group who have been found to free ride more than others in repeated studies is people who have studied economics. In a study published in 1993, Robert Frank and colleagues from Cornell University, in Ithaca, New York State, tested this idea with a version of the prisoner’s dilemma game. Economics students “informed on” other players 60% of the time, while those studying other subjects did so 39% of the time. Men have previously been found to be more self-interested in such tests, and more men study economics than women. However even after controlling for this sex difference, Frank found economics students were 17% more likely to take the selfish route when playing the prisoner’s dilemma.

In good news for educators everywhere, the team found that the longer students had been at university, the higher their rates of cooperation. In other words, higher education (or simple growing up), seemed to make people more likely to put their faith in human co-operation. The economists again proved to be the exception. For them extra years of study did nothing to undermine their selfish rationality.

Frank’s group then went on to carry out surveys on whether students would return money they had found or report being undercharged, both at the start and end of their courses. Economics students were more likely to see themselves and others as more self-interested following their studies than a control group studying astronomy. This was especially true among those studying under a tutor who taught game theory and focused on notions of survival imperatives militating against co-operation.

Subsequent work has questioned these findings, suggesting that selfish people are just more likely to study economics, and that Frank’s surveys and games tell us little about real-world moral behaviour. It is true that what individuals do in the highly artificial situation of being presented with the prisoner’s dilemma doesn’t necessarily tell us how they will behave in more complex real-world situations.

In related work, Eric Schwitzgebel has shown that students and teachers of ethical philosophy don’t seem to behave more ethically when their behaviour is assessed using a range of real-world variables. Perhaps, says Schwitzgebel, we shouldn’t be surprised that economics students who have been taught about the prisoner’s dilemma, act in line with what they’ve been taught when tested in a classroom. Again, this is a long way from showing any influence on real world behaviour, some argue.

The lessons of what people do in tests and games are limited because of the additional complexities involved in real-world moral choices with real and important consequences. Yet I hesitate to dismiss the results of these experiments. We shouldn’t leap to conclusions based on the few simple experiments that have been done, but if we tell students that it makes sense to see the world through the eyes of the selfish rational actor, my suspicion is that they are more likely to do so.

Multiple factors influence our behaviour, of which formal education is just one. Economics and economic opinions are also prominent throughout the news media, for instance. But what the experiments above demonstrate, in one small way at least, is that what we are taught about human behaviour can alter it.

This is my column from BBC Future last week. You can see the original here. Thanks to Eric for some references and comments on this topic.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers