Tom Stafford's Blog, page 42

December 18, 2013

The best graphic and gratuitious displays

Forget your end of year run-downs and best of 2013 photo specials, it doesn’t get much better than this: ‘The 15 Best Behavioural Science Graphs of 2010-13′ from the Stirling Behavioural Science Blog.

As to be expected, some are a little better than others (well, Rolling Stone chose a Miley Cyrus video as one of their best of 2013, so, you know, no-one’s perfect) but there are still plenty of classics.

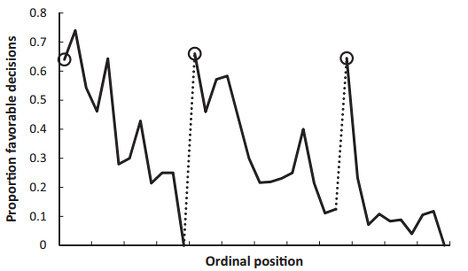

This one, from a study on parole rulings by judges based on the order of cases and when food breaks occur is particularly eye-opening.

This paper examined 1,112 judicial rulings over a 10 month period by eight judges in Israel. These judges presided over 2 parole boards for four major prisons, processing around 40% of all parole requests in the country. They considered 14-35 cases per day for an average of six minutes and they took two daily food breaks (a late morning snack and lunch), dividing the day into three sessions.

The graph looks at the proportion of rulings in favor of parole by ordinal position (so 1st case of the day, then 2nd, then 3rd, etc). The circled points are the first decision in each of the three decision sessions, the tick marks on the x-axis denote every third case and the dotted line denotes a food break. The probability of the judges granting parole falls steadily from around 65% to nearly zero just before the break, before jumping back up again after they return to work.

Moral of the story: don’t get banged up, make sure your judge has been recently fed, or bring snacks to court.

Anyway, plenty more fascinating behavioural science graphs to check out and no Miley Cyrus. At least, until she jumps on that bandwagon.

Link to ‘The 15 Best Behavioural Science Graphs of 2010-13′

December 15, 2013

A disorder of marketing

The New York Times has an important article on how Attention Deficit Disorder, often known as ADHD, has been ‘marketed’ alongside sales of stimulant medication to the point where leading ADHD researchers are becoming alarmed at the scale of diagnosis and drug treatment.

The New York Times has an important article on how Attention Deficit Disorder, often known as ADHD, has been ‘marketed’ alongside sales of stimulant medication to the point where leading ADHD researchers are becoming alarmed at the scale of diagnosis and drug treatment.

It’s worth noting that although the article focuses on ADHD, it is really a case study in how psychiatric drug marketing often works.

This is the typical pattern: a disorder is defined and a reliable diagnosis is created. A medication is tested and found to be effective – although studies which show negative effects might never be published.

It is worth highlighting that the ‘gold standard’ diagnosis usually describes a set of symptoms that are genuinely linked to significant distress or disability.

Then, marketing money aims to ‘raise awareness’ of the condition to both doctors and the public. This may be through explicit drug company adverts, by sponsoring medical training that promotes a particular drug, or by heavily funding select patient advocacy groups that campaign for wider diagnosis and drug treatment.

This implicitly encourages diagnosis to be made away from the ‘gold standard’ assessment – which often involves an expensive and time-consuming structured assessment by specialists.

This means that much of the diagnosis and prescribing happens by local doctors and is often prompted by patients turning up with newspaper articles, adverts, or the results of supposedly non-diagnostic diagnostic quizzes in their hands. There are many more marketing tricks of the trade which the article goes through in detail.

As the initial market begins to become saturated, drug companies will often aim to ‘expand’ into other areas by sponsoring studies into the same condition in another age group and treating the condition as an ‘add on’ to another disorder – each of which allows them to officially market the drug for these conditions.

However, fines for illegally marketing drugs for non-approved conditions are now commonplace are many think that these are just considered as calculated financial risks by pharmaceutical companies.

The New York Times is particularly important because it tracks the entire web of marketing activity – that aside from the traditional medical slant – also includes pop stars, material for kids, TV presenters, websites and bloggers.

It is a eye-opening guide to the burgeoning world of ADHD promotion but is really just a case study of how psychiatric drug marketing works. By the way, don’t miss the video that analyses the marketing material.

Essential stuff.

Link to NYT article ‘The Selling of Attention Deficit Disorder’

December 14, 2013

2013-12-13 Spike activity

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Beware the enthusiasm for ‘neuroeducation’ says Steven Rose in Times Higher Education.

Lots of studies use oxytocin nasal sprays. You can buy it from websites. Neuroskeptic asks does it even reach the brain?

Time magazine finds a fascinating AI telemarketer bot that denies it’s a robot when questioned – with some great audio samples of the conversations.

The Tragedy of Common-Sense Morality. Interesting interview with psychologist of moral thinking Joshua Green in Slate.

Brain Watch takes a calm look at the most hyped concept in neuroscience: mirror neurons.

As is traditional the Christmas British Medical Journal has some wonderfully light-hearted science – including a medical review on the beneficial and harmful effects of laughter.

How much do we really know about sleep? asks The Telegraph.

Chemical adventurers: a potent laboratory neurotoxin is being sold as a legal high online. The Dose Makes The Poison has the news.

Not really into kickstarters but this looks cool: open-source Arduino-compatible 8-channel EEG platform.

Did Brain Scans Just Save a Convicted Murderer From the Death Penalty? Wired on a curious neurolaw development.

How the US military used lobotomies on World War II veterans – an excellent multimedia expose from the Wall Street Journal.

New Scientist takes a critical look at the ‘genetics more important than experience in school exam performance’ study that’s been making the headlines.

The Manifestation of Migraine in Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Neurocritic on migraine and opera.

December 10, 2013

How sleep makes your mind more creative

It’s a tried and tested technique used by writers and poets, but can psychology explain why first moments after waking can be among our most imaginative?

It is 6.06am and I’m typing this in my pyjamas. I awoke at 6.04am, walked from the bedroom to the study, switched on my computer and got to work immediately. This is unusual behaviour for me. However, it’s a tried and tested technique for enhancing creativity, long used by writers, poets and others, including the inventor Benjamin Franklin. And psychology research appears to back this up, providing an explanation for why we might be at our most creative when our minds are still emerging from the realm of sleep.

The best evidence we have of our mental state when we’re asleep is that strange phenomenon called dreaming. Much remains unknown about dreams, but one thing that is certain is that they are weird. Also listening to other people’s dreams can be deadly boring. They go on and on about how they were on a train, but it wasn’t a train, it was a dinner party, and their brother was there, as well as a girl they haven’t spoken to since they were nine, and… yawn. To the dreamer this all seems very important and somehow connected. To the rest of us it sounds like nonsense, and tedious nonsense at that.

Yet these bizarre monologues do highlight an interesting aspect of the dream world: the creation of connections between things that didn’t seem connected before. When you think about it, this isn’t too unlike a description of what creative people do in their work – connecting ideas and concepts that nobody thought to connect before in a way that appears to make sense.

No wonder some people value the immediate, post-sleep, dreamlike mental state – known as sleep inertia or the hypnopompic state – so highly. It allows them to infuse their waking, directed thoughts with a dusting of dreamworld magic. Later in the day, waking consciousness assumes complete control, which is a good thing as it allows us to go about our day evaluating situations, making plans, pursuing goals and dealing rationally with the world. Life would be challenging indeed if we were constantly hallucinating, believing the impossible or losing sense of what we were doing like we do when we’re dreaming. But perhaps the rational grip of daytime consciousness can at times be too strong, especially if your work could benefit from the feckless, distractible, inconsistent, manic, but sometimes inspired nature of its rebellious sleepy twin.

Scientific methods – by necessity methodical and precise – might not seem the best of tools for investigating sleep consciousness. Yet in 2007 Matthew Walker, now of the University of California at Berkeley, and colleagues carried out a study that helps illustrate the power of sleep to foster unusual connections, or “remote associates” as psychologists call them.

Under the inference

Subjects were presented with pairs of six abstract patterns A, B, C, D, E and F. Through trial and error they were taught the basics of a hierarchy, which dictated they should select A over B, B over C, C over D, D over E, and E over F. The researchers called these the “premise pairs”. While participants learnt these during their training period, they were not explicitly taught that because A was better than B, and B better than C, that they should infer A to be better than C, for example. This hidden order implied relationships, described by Walker as “inference pairs”, were designed to mimic the remote associates that drive creativity.

Participants who were tested 20 minutes after training got 90% of premise pairs but only around 50% of inference pairs right – the same fraction you or I would get if we went into the task without any training and just guessed.

Those tested 12 hours after training again got 90% for the premise pairs, but 75% of inference pairs, showing the extra time had allowed the nature of the connections and hidden order to become clearer in their minds.

But the real success of the experiment was a contrast in the performances of one group trained in the morning and then re-tested 12 hours later in the evening, and another group trained in the evening and brought back for testing the following morning after having slept. Both did equally well in tests of the premise pairs. The researchers defined inferences that required understanding of two premise relationships as easy, and those that required three or more as hard. So, for example, A being better than C, was labelled as easy because it required participants to remember that A was better than B and B was better than C. However understanding that A was better than D meant recalling A was better than B, B better than C, and C better than D, and so was defined as hard.

When it came to the harder inferences, people who had a night’s sleep between training and testing got a startling 93% correct, whereas those who’d been busy all day only got 70%.

The experiment illustrates that combining what we know to generate new insights requires time, something that many might have guessed. Perhaps more revealingly it also shows the power of sleep in building remote associations. Making the links between pieces of information that our daytime rational minds see as separate seems to be easiest when we’re offline, drifting through the dreamworld.

It is this function of sleep that might also explain why those first moments upon waking can be among our most creative. Dreams may seem weird, but just because they don’t make sense to your rational waking consciousness doesn’t make them purposeless. I was at my keyboard two minutes after waking up in an effort to harness some dreamworld creativity and help me write this column – memories of dreams involving trying to rob a bank with my old chemistry teacher, and playing tennis with a racket made of spaghetti, still tinging the edges of my consciousness.

This is my BBC Future column from last week. The original is here. I had the idea for the column while drinking coffee with Helen Mort. Caffeine consumption being, of course, another favourite way to encourage creativity!

December 8, 2013

Where data meets the people

Ben Goldacre might be quite surprised to hear he’s written a sociology book, but for the second in our series on books about how the science of mind, brain and mental health meet society, Bad Pharma is an exemplary example.

Ben Goldacre might be quite surprised to hear he’s written a sociology book, but for the second in our series on books about how the science of mind, brain and mental health meet society, Bad Pharma is an exemplary example.

The book could essentially be read as a compelling textbook on clinical trial methodology with better jokes, but the crux of the book is not really the methods of testing medical interventions, but how these methods are used and abused for financial ends and what impact this has on professional medicine and, ultimately, our health.

In other words, the book looks at how clinical science is used socially and how social influences affect clinical science.

For example, this is question I often give students: If a trial is badly designed, are the results more likely to suggest the treatment is effective or more likely to suggest the treatment is ineffective?

Most students, naive to the ways of the scientific world, tend to say that badly designed trials would be less likely to show the treatment works but in the real world, badly designed trials are much more likely to give positive results.

There is nothing in the science that makes this happen. This is an entirely social effect. It’s worth saying that that this is rarely due to outright fraud but it’s those little decisions that add up over time, each of which seems completely justifiable to the researcher, that sway the results.

It’s like if your dad was school football coach. You’d probably get picked for the team more often not because your father was making a conscious decision to include you no matter what, but because he would genuinely believe he had recognised talent where others probably wouldn’t.

For scientists, the treatment they are testing is often their ‘baby’, and the same sort of soft biases creep in between the cracks. And the more cracks there are, the more creep occurs.

On the other hand, pharmaceutical companies are often deliberately trying to promote their product by distorting the evidence for its effectiveness. This often happens within the accepted regulations – the unethical but legal realm – but happens surprisingly often outside the law.

Bad Pharma is not specifically about psychiatry but as one of the medical specialities which is most corrupted by the influence of large pharmaceutical companies, it turns up a lot.

It is both an essential guide to understanding how treatments for mental health conditions are tested and has plenty of examples of how psychiatric drugs have been the subject of spin, over-selling and fraud.

Perhaps the only part where I think Goldacre is being too strong is in his criticism of ‘me too drugs’ which are new drugs which are often molecularly similar but no more effective for the target symptoms than the old ones.

At least in psychiatry, one of the big problems is not so much the effectiveness of the drugs, but their side-effects. Having other compounds which although no more effective may be more agreeable or less risky is a genuine benefit.

Goldacre is clear about this being a benefit, but I think he under-values it at times, especially since a lot of mind and brain medicine involves iterating through medications until the patient is happy with the balance between effectiveness and side-effects.

But this is a small point in an excellent book. It is essential if you want to know how medicine works and doubly essential if you have an interest in the mind, brain and mental health where these issues are both a significant battle ground and often under-appreciated.

I suspect Goldacre would prefer to call the book political rather than sociological, but if you are studying psychology, neuroscience or mental health it is a must read to understand how clinical science meets society.

Next and finally in this three-part Mind Hacks series on science and society – Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman’s The Empire of Trauma.

Link to more details of Bad Pharma.

December 6, 2013

2013-12-06 Spike activity

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

C-List celebrity is photographed with a psychology book in her hand and New York Magazine is all over it like Glenn Greenwald with an encrypted harddrive.

The New York Times covers a Dutch scheme to get alcoholics working by paying them in beer. Scheme to get stoners working by paying them in weed probably not as effective.

The British Medical Journal has an entertaining interview with psychiatrist Simon Wessely.

Soaring dementia rates prompt call for global action, reports New Scientist.

Bloomberg reports that the rate of US teens on psychiatric drugs remains steady at 6%. Hey, it could be worse.

Research on illicit drugs is being hampered by daft drug laws says David Nutt in Scientific America. Clearly not the worst scientific censorship “since the banning of the telescope” but the point remains.

Brain Watch has a good round up of discussions surrounding the ‘men and women’s brains are wired differently therefore stereotypes’ study that has been getting everyone’s unisex underwear in a twist.

Electric brain stimulation triggers eye-of-the-tiger effect. Not Exactly Rocket Science has the power-chords (and maybe the power cords – hard to see from this angle).

NPR has one of the few left-brain / right-brain articles you’ll ever want to read. Neuroscientist Tania Lombroso takes a detailed look at the science behind the concept.

The science of hatred. The Chronicle of Higher Education has an excellent piece on the psychology of genocide and racism.

Hallucinated voices and the community inside us

I’ve long been fascinated by the experience of ‘hearing voices’ and long been baffled by the typical scientific approach to the experience.

I’ve long been fascinated by the experience of ‘hearing voices’ and long been baffled by the typical scientific approach to the experience.

As a result, I’ve just had a paper published in PLOS Biology that focus on one of the most striking but ignored aspects of hallucinated voices.

Here’s how I describe the central paradox in the paper:

Auditory verbal hallucinations, the experience of “hearing voices”, present us with an interesting paradox: the experiences are generated from within a single individual but are typically experienced as a social phenomenon—that is, a form of communication from another speaker.

Current theories attempt to explain auditory verbal hallucinations as alterations to individualistic information processing—namely, misattributions of internal thoughts as external phenomena due to biases in cognitive monitoring.

The fact that voices stem from an internal source is, of course, clear, but the typical experience of “hearing voices” is not that thoughts seem to be “spoken aloud” but that hallucinated voices have a social identity with clear interpersonal relevance. In other words, voices are as much hallucinated social identities as they are hallucinated words or sounds.

The article discusses the psychology and neuroscience of social processing in the experience of hearing voices and suggests how we can begin to consider this as a central component of the experience in terms of scientific research.

It’s an academic article but should hopefully be fairly accessible to most people with an interest in the science of hallucinations.

Enjoy!

Link to article ‘A Community of One’ on social cognition and hearing voices.

December 4, 2013

London’s Shuffle Festival is back

London’s film, food and science festival in an abandoned psychiatric hospital is back as the Shuffle Festival kicks off its Winter run.

Hosted in the old buildings of St Clement’s Hospital the festival has an impressive programme including everything from Jarvis Cocker to Brian Cox.

There are also regular talks from working scientists including a couple of standout-looking ones on the neuroscience of religious experience and circadian rhythms.

There’s also a full film programme, DJs, a restaurant, music, theatre and an art gallery with a commissioned show.

As with the summer Shuffle Festival, the profits go to the East London Community Land Trust that will ensure that when the hospital gets redeveloped, affordable housing will be available to the local community. A welcome change from the usual practice of converting London’s old asylums into exorbitant luxury flats.

If it’s anything like last time, it should be awesome. And if you didn’t go in August, this may be your last chance to say you’ve experienced a festival in an abandoned Victorian-era asylum.

The full programme is at the link below. See you there!

Link to the Shuffle Festival.

December 3, 2013

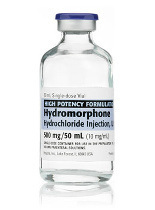

A life in the day of a medical morphine addict

AddictionBlog has an amazing article by a doctor and recovering morphine addict that describes the experience of injection, rush and withdrawal.

AddictionBlog has an amazing article by a doctor and recovering morphine addict that describes the experience of injection, rush and withdrawal.

It’s wonderfully written to the point of being painful and if you’re not good with needles, you’ll probably feel a bit queasy when reading it.

Heroin, by the way, is just the prodrug of morphine. In other words, the heroin molecule just gets broken down into morphine in the body and this is how it arrives in the brain.

But because each heroin molecule gets transformed into two morphine molecules (hence the medical name for heroin – diamorphine) the feeling can be a little different because increased concentration can apparently make the high more intense.

Neurochemically, however, the action in each opioid receptor is the same.

As morphine is used more widely in medicine than diamorphine, it is more likely to be used and turn up in cases of addiction.

As we’ve discussed previously, addiction and abuse of medical drugs by doctors is linked to clinical speciality – likely due to both knowledge of and access to particular compounds.

The AddictionBlog article is a strikingly written, honest, detailed and psychologically insightful piece if you want an insight into this curious corner of medical drug abuse.

Link to ‘What it’s like to take and withdraw from morphine’

Are men better wired to read maps or is it a tired cliché?

By Tom Stafford

The headlines

The Guardian: Male and female brains wired differently, scans reveal

The Atlantic: Male and female brains really are built differently

The Independent: The hardwired difference between male and female brains could explain why men are ‘better at map reading

The Story

An analysis of 949 brain scans shows significant sex differences in the connections between different brain areas.

What they actually did

Researchers from Philadelphia took data from 949 brain scans and divided them into three age groups and by gender. They then analysed the connections between 95 separate divisions of each brain using a technique called Diffusion Tensor Imaging.

With this data they constructed “connectome” maps, which show the network of the strength of connection between those brain regions.

Statistical testing of this showed significant differences between these networks according to sex – the average men’s network was more connected within each side of the brain, and the average women’s network was better connected between the two hemispheres. These differences emerged most strongly after the age of 13 (so weren’t as striking for the youngest group they tested).

How plausible is this?

Everybody knows that men are women have some biological differences – different sizes of brains and different hormones. It wouldn’t be too surprising if there were some neurological differences too. The thing is, we also know that we treat men and women differently from the moment they’re born, in almost all areas of life. Brains respond to the demands we make of them, and men and women have different demands placed on them.

Although a study of brain scans has an air of biological purity, it doesn’t escape from the reality that the people having their brains scanned are the product of social and cultural forces as well as biological ones.

The research itself is a technical tour-de-force which really needs a specialist to properly critique. I am not that specialist. But a few things seem odd about it: they report finding significant differences between the sexes, but don’t show the statistics that allow the reader to evaluate the size of any sex difference against other factors such as age or individual variability. This matters because you can have a statistically significant difference which isn’t practically meaningful. Relative size of effect might be very important.

For example, a significant sex difference could be tiny compared to the differences between people of different ages, or compared to the normal differences between individuals. The question of age differences is also relevant because we know the brain continues to develop after the oldest age tested in the study (22 years).

Any sex difference could plausibly be due to difference in the time-course of development between men and women. But, in general, it isn’t the technical details which I am equipped to critique. It’s a fair assumption to believe what the researchers have found, so let’s turn instead to how it is being interpreted.

Tom’s take

One of the authors of this research, as reported in The Guardian, said “the greatest surprise was how much the findings supported old stereotypes”. That, for me, should be a warning sign. Time and time again we find, as we see here, that highly technical and advanced neuroscience is used to support tired old generalisations.

Here, the research assumes the difference it seeks to prove. The data is analysed for sex differences with other categories receiving less or no attention (age, education, training and so on). From this biased lens on the data, a story about fundamental differences is also told. Part of our psychological make-up seems to be to want to assign essences to things – and differences between genders is a prime example of something people want to be true.

Even if we assume this research is reliable it doesn’t tell us about actual psychological differences between men and women. The brain scan doesn’t tell us about behaviour (and, indeed, most of us manage to behave in very similar ways despite large differences in brain structure and connectivity). Bizarrely, the authors seem also to want to use their analysis to support a myth about left brain vs right brain thinking. The “rational” left brain vs the intuitive’ right brain is a distinction that even Michael Gazzaniga, one of the founding fathers of “split brain” studies doesn’t believe any more.

Perhaps more importantly, analysis of how men and women are doesn’t tell you how men and women could be if brought up differently.

When the headlines talk about “hardwiring” and “proof that men and women are different” we can see the role this research is playing in cementing an assumption that people have already made. In fact, the data is silent on how men and women’s brains would be connected if society put different expectations on them.

Given the surprising ways in which brains do adapt to different experiences, it is completely plausible that even these significant “biological” differences could be due to cultural factors.

And even reliable differences between men and women can be reversed by psychological manipulations, which suggests that any underling biological differences isn’t as fundamental as researchers like to claim.

As Shakespeare has Ophelia say in Hamlet: “Lord, we know what we are, but know not what we may be.”

Read more

The original paper: Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain

Sophie Scott of UCL has some technical queries about the research – one possibility is that movements made during the scanning could have been different between the sexes and generated the apparent differences in the resulting connectome networks.

Another large study, cited by this current paper, found no differences according to sex.

Cordelia Fine’s book, Delusions of gender: how our minds, society, and neuro-sexism create difference provides essential context for looking at this kind of research.

Tom Stafford does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers