Tom Stafford's Blog, page 27

November 16, 2014

An earlier illusory death

For such an obscure corner of the medical literature, Cotard’s delusion is remarkably well known as the delusion that you’re dead. This was supposedly first described by Jules Cotard in 1880 but I seem to have found a description from 1576.

For such an obscure corner of the medical literature, Cotard’s delusion is remarkably well known as the delusion that you’re dead. This was supposedly first described by Jules Cotard in 1880 but I seem to have found a description from 1576.

It’s worth noting that although Cotard’s delusion has come to represent ‘the delusion that you’re dead’, Jules Cotard’s original description was not actually that – it was a delusion of negation where the patient believed, as noted by Berrios and Luque, that she had “no brain, nerves, chest, or entrails, and was just skin and bone”, that “neither God or the devil existed”, and that she did not need food for “she was eternal and would live forever”.

In its modern use, Cotard’s delusion typically refer to the belief that you’re dead, you don’t exist, or that your body is rotting or absent. It is rare but can occur in severe psychosis.

While spending my weekend reading Basil Clarke’s book Mental Disorder in Earlier Britain (yes kids, I’m like Snoop Dogg but for out of print history of psychiatry books), I found a mention of not one but possibly two cases of Cotard delusion.

They were apparently described Levinus Lemnius’s 1576 book The Touchstone of Complexions, as Clarke recounts:

A ‘Hypochondriake person’ was unshakeably convinced that frogs and toads were eating his entrails. This was accepted, and he was given purges and enemas, the doctor slipping ‘crawlynge vermyne’ into the pot to satisfy him. A case of a man who thought his buttocks were made of glass was incomplete. Another patient had fallen into ‘such an agonie, & fooles paradise’ that he thought he was dead and gave up eating. After a week, friends came into the dark parlour in shrouds and settled down for a meal. The ‘Passioned Party’, on asking, was told that they were dead and that dead men ate and drank. ‘Straightwayes skipped this Pacient out of his Bedde and joined them.’ After supper he was given a sleeping draught.

The mention of the man who believed he had glass buttocks is also interesting as this is the glass delusion, the belief that you are made of glass and might shatter.

This was apparently common in cases of madness during the Late Middle Ages but is now virtually non-existent. Famously, it affected Charles VI of France.

November 15, 2014

More on the enigma of blindness and psychosis

A long-standing enigma in psychiatry has been why no-one has been able to find someone who has both congenital blindness and a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The newest and most comprehensive archive study to date has just been published on exactly this issue although it raises more questions than it answers.

A long-standing enigma in psychiatry has been why no-one has been able to find someone who has both congenital blindness and a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The newest and most comprehensive archive study to date has just been published on exactly this issue although it raises more questions than it answers.

Evelina Leivada and Cedric Boeckx from the University of Barcelona in Spain conducted an extensive medical literature search and did come up with some cases of congenital blindness and schizophrenia – 13 in total, although only two case studies (outlining a total of four cases) were found which were convincing enough to be unaffected by other serious problems, like severe genetic disorders.

And these remaining four were hardly straightforward and as one report was from 1943 and the other from 1967 where standards of both vision and psychiatric assessment were significantly short of modern standards.

Notably, all cases of co-occurrence were from blindness due to eye problems or where blindness happened relatively late (after 6 years of age). No cases were found were people had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and were congenitally cortically blind – where blindness was caused by problems with the brain’s visual system.

What this new study provides is weak evidence for the possibility of certain sorts of blindness coexisting with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and more comprehensive support for the curious finding that blindness seems to reduce the risk of developing psychosis.

It’s worth noting that what is really needed is a prospective epidemiological study of psychosis in blind people. However, researchers have been searching for congenitally blind people with psychosis since the issue of non-co-occurrence was first seriously raised in the 1980s and none have been found. Based on the rates of occurrence for each condition, the combination should be fairly common. This suggests that hypothesis of protective effects of congenital blindness needs to taken seriously.

The Leivada and Boeckx paper goes on to speculate about neuropsychological reasons why congenital blindness might protect against schizophrenia (essentially, changes in the interaction between key visual system components and the language system) and, somewhat less convincingly, genetic reasons – as just extrapolating likely genes from case studies is very speculative and both the eye and brain develop from the same cells during embryo development so it’s not clear shared genes won’t just reflect generally impaired neurodevelopment.

I have to say, I find the concept of schizophrenia to be a fairly useless, but if the increasingly plausible hypothesis that congenital blindness protects against psychosis is confirmed, it has interesting implications for those that argue that psychosis is nothing but the result of marginalisation, stigma or difficult life circumstances where biological explanations are irrelevant.

Blindness, clearly would increase your chances of all of these, and so on this theory, we would expect an increased rate of psychosis, but this doesn’t seem to be the case.

It’s not that marginalisation, stigma or difficult life circumstances aren’t causal factors in developing psychosis, they clearly are, but ignoring neuro-level explanations outside these effects is equally as narrow as suggesting that they are the only relevant influences.

Link to ‘Schizophrenia and cortical blindness’ in Frontiers.

November 14, 2014

Spike activity 14-11-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

The Chronicle of Higher Education has an excellent piece arguing for more focus on developing good theories of the brain amid the cascade of cash for neuroscience methods.

Moving Beyond Left Brain, Right Brain, Neuroskeptic goes in-depth with Michael Corballis. More neuronerd goodness from PLOS Neuro.

Nature magazine has a special open-access special on depression.

The Air Loom is short film based on the madness of James Tilly Matthews.

Neuroskeptic has some more wonderful etymological maps of the brain.

When we lie to children, are we teaching them to be dishonest? Interesting piece from the BPS Research Digest.

BBC News reports on a colour blind artist who had a camera implanted in his skull to allow him to hear colours.

There’s a good post on Providentia on Barnum statements and the psychology of vague complements.

Trifles make the sum of life

I’ve just found a curious scientific paper that looks at whether computational models of neural function are of relevance to clinical psychiatry. Oddly, it is written as a debate between two Charles Dickens characters.

I’ve just found a curious scientific paper that looks at whether computational models of neural function are of relevance to clinical psychiatry. Oddly, it is written as a debate between two Charles Dickens characters.

The paper was published in the journal Neural Networks and is entitled “Are computational models of any use to psychiatry?”.

It starts entirely normally and then suddenly introduces two characters from the novel David Copperfield who begin to discuss the cognitive science of computational psychiatry.

Wise old Dr. Strong (Dickens, 1850) will now put the case against CMs [computational models] from the point of view of a psychiatrist. Our optimistic – or maybe unrealistic – friend Mr. Micawber will try to enthuse him about their cause. He is also a fan of reinforcement learning models.

It’s worth noting that in the original version of David Copperfield, Mr. Micawber barely mentions his admiration of computational reinforcement learning models (reading between the lines, he always seemed more of learning mechanism agnostic autoassociative memory man to me – but hey, I’m no English literature scholar).

Dr. Strong: First and foremost, CMs have failed to influence clinical practice.

Mr. Micawber: I would agree, Dr. Strong, that CMs have not influenced clinical practice to date; but neither have most advances in neurosciences. In fact, we believe that CMs will be instrumental in helping to bridge the gap between neurobiology and psychiatry because CMs are able to link levels of descriptions and make well-founded predictions at one level based on information at another level.

Dr. Strong: I disagree. The question is: are they clinically relevant, not will they be at some point in the future. All the models omit the very centre of psychiatry: subjective experiences. No one I have met believes that computers feel duty, personal bonds, or sexual titillation.

Weirdly, this is not the first cognitive science paper to be presented as a debate between two rather unexpected people.

Jerry Fodor’s paper “Fodor’s Guide to Mental Representation: The Intelligent Auntie’s Vade-Mecum” involves a discussion between him and his aunty about the finer points of mental representation.

Sadly, the paper is behind a pay-wall because Elsevier know that the cognitive science / Dickens combination can be deadly in the wrong hands.

Link to locked article “Are computational models of any use to psychiatry?”

Hearing WiFi

New Scientist has a fascinating article on Frank Swain who has hacked his hearing aid to allow him to hear WiFi.

New Scientist has a fascinating article on Frank Swain who has hacked his hearing aid to allow him to hear WiFi.

It’s a great idea and riffs on various attempts to ‘extend’ perception into the realm of being able to sense the usually unnoticed electromagnetic environment.

I am walking through my north London neighbourhood on an unseasonably warm day in late autumn. I can hear birds tweeting in the trees, traffic prowling the back roads, children playing in gardens and Wi-Fi leaching from their homes. Against the familiar sounds of suburban life, it is somehow incongruous and appropriate at the same time.

As I approach Turnpike Lane tube station and descend to the underground platform, I catch the now familiar gurgle of the public Wi-Fi hub, as well as the staff network beside it. On board the train, these sounds fade into silence as we burrow into the tunnels leading to central London.

I have been able to hear these fields since last week. This wasn’t the result of a sudden mutation or years of transcendental meditation, but an upgrade to my hearing aids. With a grant from Nesta, the UK innovation charity, sound artist Daniel Jones and I built Phantom Terrains, an experimental tool for making Wi-Fi fields audible.

Do also check out a fantastic radio documentary by Swain we featured earlier this year which is a brilliant auditory journey into the physics and hacking of hearing and hearing loss.

Link to NewSci article ‘From under-hearing to ultra-hearing’

November 7, 2014

Spike activity 07-11-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

The odd beauty of 60-Year-old preserved brains from the Texas State Mental Hospital. Photo series from the Washington Post.

The Concourse has an interesting piece by an ex-con who discusses violence as a social currency in the US prison system. Interesting contrast between forensic treatment and inmate views of how violence works.

The latest series of BBC Radio 4’s All in the Mind has just started and has hit the wires.

‘Taboo’ sexual fantasies are surprisingly common according to a study covered by Pacific Standard – see also the epidemiology of internet pornography.

The Scientist has an interesting and extensive piece on advances in face perception research.

Robots for the brain and neuroprosethics for the mind. Interesting Olaf Blanke talk.

Excellent retrospective of 50 years of methadone in Washington Monthly.

We’re Sexist Toward Robots. Sounds trivial but stay with it, actually quite an interesting piece in Motherboard.

Reddit AMA with Vanessa Tolosa – neuroscientist who develops implantable neural devices.

Fascinating BBC News article on the prehistoric population of Europe and the mystery group who brought farming with them.

Beautiful online neuroscience learning

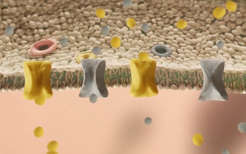

The Fundamentals of Neuroscience is a free online course from Harvard and it looks wonderful – thanks to them employing animators, digital artists and scientists to lift the course above the usual read and repeat learning.

The Fundamentals of Neuroscience is a free online course from Harvard and it looks wonderful – thanks to them employing animators, digital artists and scientists to lift the course above the usual read and repeat learning.

The course is already underway but you can register and start learning until mid-December and you can watch any of the previews to get a feel for what’s being taught.

As you can see from the syllabus it focuses on the fairly low-level operation of the biology of brain but it’s all essential knowledge that will undoubtedly be a joy to encounter or re-acquaint yourself with.

You need to register to access the full content but there’s plenty of trailers online. Great stuff.

Link to ‘Fundamentals of Neuroscience’ course.

November 4, 2014

Hallucinogenic bullets

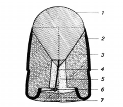

An article in the American Journal of Forensic Medicine & Pathology discusses the history of ‘modern toxic antipersonnel projectiles’ and it has a short history of ammunition designed to introduce incapacitating hallucinogenic substances into the body.

An article in the American Journal of Forensic Medicine & Pathology discusses the history of ‘modern toxic antipersonnel projectiles’ and it has a short history of ammunition designed to introduce incapacitating hallucinogenic substances into the body.

As you might expect for such an unpleasant idea (chemical weapon hand guns!) they were wielded by some fairly unpleasant people

The Nazi Institute of Criminology then ordered a batch of more powerful 9-mm Parabellum cartridges that could be used with the Walther P38. This time the bullets contained Ditran, a mixture of 2 structural isomers comprising approximately 70% 1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinylmethyl-alpha-phenylcyclopentylglycolate and 30% 1-ethyl-3-piperidyl-alpha-phenylcyclopentylglycolate (also known as Ditran B). Ditran B is the more active of the 2 isomers, both of which are strong anticholinergic drugs with hallucinogenic properties similar to those of scopolamine. Victims are thrown into such a state of mental confusion that they are incapable of reacting appropriately to the situations they find themselves in…

3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate, also known as QNB and coded BZ by NATO, is a military incapacitating agent. Like Ditran, it is an anticholinergic causing such intense mental confusion as to prevent any effective reaction against an enemy. These bullets were featured in the arsenal of the Serbian forces invading Bosnia-Herzegovina, particularly in Srebrenica in the 1990s.

Link to locked article ‘Modern Toxic Antipersonnel Projectiles’

November 2, 2014

Mind Hacks – Live!

At the end of November, we’ll be celebrating 10 years of Mind Hacks, and we’re putting on a live event in London to celebrate. You are cordially invited.

At the end of November, we’ll be celebrating 10 years of Mind Hacks, and we’re putting on a live event in London to celebrate. You are cordially invited.

Mind Hacks – Live! will be like the blog, but live, and with less scrolling.

Some of the details are still under construction, but here’s what we know:

Tom and Vaughan have hired London’s Grant Museum of Zoology. which will be like having the event inside a Victorian display case of science. But instead of looking at the exhibits, they’ll be looking at us. Awesome and wonderfully weird venue which you shouldn’t miss.

It’s in Central London, and Mind Hacks – Live! will be on Thursday 20th November 7pm to 9pm.

We’ve also got some fantastic speakers lined up:

Science wrangler Ed Yong will be talking about the real science behind media favourite oxytocin.

We’re hoping neuroscientist Sophie Scott is going to give us a whirlwind tour of the neuroscience of laughter.

Blogger, neuroscientist and international man of mystery Neuroskeptic will be talking about “something cool”.

Neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore is going to be debunking myths about the neuroscience of education and the teenage brain.

Cognitive scientist and Mind Hacks mastermind Tom Stafford is going to talk on ‘The Game': Are ‘Pickup Artists’ the ultimate Mind Hackers?

And we’re going to end on a serious note that should also serve as a stark warning to us all.

The sex scene from Susan Greenfield’s future-noir novel 2121 will be given a dramatised reading with Neuroskeptic and Vaughan Bell playing the protagonists who struggle to remember how to have sex because their brains have been mashed by the internet. Live and direct, people.

If you miss a ticket for the event, come have a drink with us after anyway. We’ll be just round the corner at The Marlborough Arms on Torrington Place (WC1E 7HJ) after the event and we’d love to see you.

Tickets for the event will cost £4 to cover costs, and you’ll receive a free commemorative email with every purchase.

Link to buy tickets for Mind Hacks – Live!

October 31, 2014

Spike activity 31-10-2014

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Nautilus has an interesting piece on how artificial intelligence systems are getting better at strategy.

Two neuroscientists explain why zombies have so much trouble walking in Slate

Vice magazine talks to a psychologist working in the Ebola outbreak in Liberia.

Neuroscientists manage to get past the blood-brain barrier for the first time potentially opening the way for getting new sorts of drugs to the brain. Covered in New Scientist.

The Neurocritic has an excellent piece on neuropsychological disorders involving mirrors.

The British are born to be miserable, according to a dreadful science story published in The Indepedent. Please note: The fact the conclusion happens to be true doesn’t mean it’s automatically good science.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers