Tom Stafford's Blog, page 24

January 21, 2015

pwned by a self-learning AI

Backchannel has a fascinating profile of DeepMind founder Demis Hassabis which although an interesting read in itself, has a link to a brief, barely mentioned study which may herald a quiet revolution in artificial intelligence.

The paper (available online as a pdf) is entitled “Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning” and describes an AI system which, without any prior training, learned to play a series of Atari 2600 games to the point of out-performing humans.

The key here is ‘without any prior training’ as the system was not ‘told’ anything about the games. It worked out how to play them, and how to win them, entirely on its own.

The system was created with a combination of a reinforcement learning system and a deep learning network.

Reinforcement learning is based on the psychological theory of operant conditioning where we learning through reward and punishment what behaviours help us achieve certain goals.

One difficulty is that in video games, the reward (points) may only be distantly related to individual actions because strategy is not something that can be boiled down to ‘do this action again to win’. Mathematically there is lots of noise in the link between an action and eventual outcome.

Traditionally this has been solved by programming the structure of the game into the AI agent. Non-player characters in video games act as effective opponents because they include lots of hard-coded rules about what different aspects of the game symbolise, and what good strategy involves.

But this is a hack that doesn’t generalise. Genuine AI would work out what to do, in any given environment, by itself.

To help achieve this, the DeepMind Atari AI uses deep learning, a hierarchical neural network that is good at generating its own structure from unstructured data. In this case, the data was just what was on the screen.

To combine ‘learning effective action’ and ‘understanding the environment’ the research team plumbed together deep learning and reinforcement learning with an algorithm called Q-learning that is specialised for ‘model-free’ or unstructured learning.

So far, we have performed experiments on seven popular ATARI games – Beam Rider, Breakout, Enduro, Pong, Q*bert, Seaquest, Space Invaders. We use the same network architecture, learning algorithm and hyperparameters settings across all seven games, showing that our approach is robust enough to work on a variety of games without incorporating game-specific information…

Finally, we show that our method achieves better performance than an expert human player on Breakout, Enduro and Pong and it achieves close to human performance on Beam Rider.

The team note that the system wasn’t so good at Q*bert, Seaquest and Space Invaders, and it wasn’t asked to battle the real K-Dan Empire after playing Starfighter, but it’s still incredibly impressive.

It’s an AI that worked out its environment, its actions, and what it needs to do to ‘survive’, without any prior information.

Given, the environment is an Atari 2600, but the AI is a surprisingly simple system that ends up, in some instances, outperforming humans from a standing start.

Essentially, the future of humanity now rests on whether the next system is given a gun or a dildo to play with.

Link to Backchannel profile of Demis Hassabis.

pdf of paper “Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning”

January 12, 2015

A love beyond illusions

Articles on people’s experience of the altered states of madness often fall into similar types: tragedy, revelation or redemption. Very few do what a wonderful article in Pacific Standard manage: give an account of how a young couple learn to live with psychosis.

Articles on people’s experience of the altered states of madness often fall into similar types: tragedy, revelation or redemption. Very few do what a wonderful article in Pacific Standard manage: give an account of how a young couple learn to live with psychosis.

It’s an interesting piece because it’s not an account of how someone finds the answer to loving someone who has episodes of psychosis, it’s how a couple find an answer.

It discusses psychiatry, antipsychotics and R.D. Laing but not in terms of what we should or could think of psychosis and society, but what one couple takes from them – finding value where it helps.

Touching, genuine, unpretentious and uncensored.

It is romantic in the truest sense.

Link to ‘My Lovely Wife in the Psych Ward’.

January 9, 2015

Spike activity 09-01-2015

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Game theorists crack poker according to a fascinating report from Nature. First nuclear war, now poker. Whatever next!

Harvard Business Review has a genuinely interesting piece on the psychology of office politics.

Child mental health services have been secretly cut by £50m according to BBC News. What we need is some important politician to tell us how important mental health is to make this right again.

British Journal of Psychiatry puts a psychedelic portrait of the Shulgins on its front cover. Rumour has it that if you lick the pages your hallucinations disappear.

There’s an interesting piece in Wired about images specifically generated to mislead AI image recognition algorithms.

The New York Times has an extended and interesting profile of innovative neuroscientist Sebastian Seung.

Can deaf people hear hallucinated voices? An interesting piece in Mosaic tackles the issue.

The scan says we add fries and call it a special

Marketing magazine has an interview with the marketing director of KFC who explains why he thinks neuroscience holds the key to selling deep-fried junk food.

Marketing magazine has an interview with the marketing director of KFC who explains why he thinks neuroscience holds the key to selling deep-fried junk food.

“Marketing as a whole is undergoing transformation,” he says. “We now know through neuroscience how people’s brains work and what affects their decision-making. So what we’re trying to do is take the new knowledge and say – this is how we put it together, this is how a brain actually works – and this is how we should be marketing.”

Somebody, please, find me a pizza.

Link to Marketing interview.

The scan says we adds fries and call it a special

Marketing magazine has an interview with the marketing director of KFC who explains why he thinks neuroscience holds the key to selling deep-fried junk food.

Marketing magazine has an interview with the marketing director of KFC who explains why he thinks neuroscience holds the key to selling deep-fried junk food.

“Marketing as a whole is undergoing transformation,” he says. “We now know through neuroscience how people’s brains work and what affects their decision-making. So what we’re trying to do is take the new knowledge and say – this is how we put it together, this is how a brain actually works – and this is how we should be marketing.”

Somebody, please, find me a pizza.

Link to Marketing interview.

Excellent NPR Invisibilia finally hits the wires

A sublime new radio show on mind, brain and behaviour has launched today. It’s called Invisibilia and is both profound and brilliant.

A sublime new radio show on mind, brain and behaviour has launched today. It’s called Invisibilia and is both profound and brilliant.

It’s produced by ex-Radiolab alumni Lulu Miller and radio journalist Alix Spiegel – responsible for some of the best mind and brain material on the radio in the last decade.

The first episode is excellent and I’ve had a sneak preview of some other material for future broadcast which is equally as good.

It’s on weekly, and you can download or stream from the link below, and you can follow the show on the Twitter @nprinvisibilia.

Recommended.

Link to NPR Invisibilia.

January 8, 2015

Is public opinion rational?

There is no shortage of misconceptions. The British public believes that for every £100 spent on benefits, £24 is claimed fraudulently (the actual figure is £0.70). We think that 31% of the population are immigrants (actually its 13%). One recent headline summed it up: “British Public wrong about nearly everything, and I’d bet good money that it isn’t just the British who are exceptionally misinformed.

This looks like a problem for democracy, which supposes a rational and informed public opinion. But perhaps it isn’t, at least according to a body of political science research neatly summarised by Will Jennings in his chapter of a new book “Sex, lies & the ballot box: 50 things you need to know about British elections“. The book is a collection of accessible essays by British political scientists, and has a far wider scope than the book subtitle implies: there are important morals here for anyone interested in collective human behaviour, not just those interested in elections.

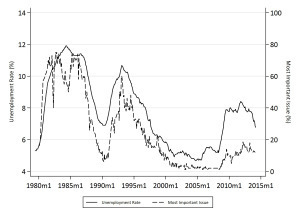

Will’s chapter discusses the “public opinion as thermostat” theory. This, briefly, is that the public can be misinformed about absolute statistics, but we can still change our strength of feeling in an appropriate way. So, for example, we may be misled about the absolute unemployment rate, but can still discern whether unemployment is getting better or worse. There’s evidence to support this view, and the chapter includes this striking graph (reproduced with permission), showing the percentage of people saying “unemployment” is the most important issue facing the country against the actual unemployment rate . As you can see public opinion tracks reality with remarkable accuracy:

Unemployment rate and share of voters rating unemployment as the most important issue facing the country, from Will Jenning’s chapter in “Sex, lie & the ballot box” (p.35)

The topic of how a biased and misinformed public can make rational collective decisions is a fascinating one, which has received attention from disciplines ranging from psychology to political science. I’m looking forward to reading the rest of the book to get more evidence based insights into how our psychological biases play out when decision making is at the collective level of elections.

Full disclosure: Will is a friend of mine and sent me a free copy of the book.

Link: “Sex, lies & the ballot box (Edited by Philip Cowley & Robert Ford).

Link: Guardian data blog Five things we can learn from Sex, Lies and the Ballot Box

January 4, 2015

Bringing us closer to the blueprints of the brain

I’ve got a piece in today’s Observer about the amazing science of doing functional brain imaging and behavioural studies with babies while they are still in the womb to see the earliest stages of neurocognitive development.

I’ve got a piece in today’s Observer about the amazing science of doing functional brain imaging and behavioural studies with babies while they are still in the womb to see the earliest stages of neurocognitive development.

Brain development during pregnancy is key for future health, which is why it gets checked so thoroughly during prenatal examinations. But neuroscientists have become increasingly interested in how the activity of the brain becomes progressively integrated and synchronised during development to support human experience, something developmental neuroscientist Moriah Thomason calls “bringing us closer to the blueprints of the brain”.

It’s difficult to state how remarkable this is, both technically and scientifically, as researchers have managed to measure the unborn brain in action as it responds to the outside world through the womb.

The article looks at how this science is developing and what it’s telling us about the earliest stages of the developing brain.

Exciting stuff.

Link to ‘Prenatal blueprints give an early glimpse of a baby’s developing brain’

December 31, 2014

A new year with an old friend

I’ve just found a curious article in the scientific journal Clinical Anatomy which reprints a Victorian story called ‘Celebrating new year in Bart’s dissecting room’ where the corpses come to life. It finishes with some interesting observations about the psychological impact of dissecting a dead body as a rite of passage for medical students.

I’ve just found a curious article in the scientific journal Clinical Anatomy which reprints a Victorian story called ‘Celebrating new year in Bart’s dissecting room’ where the corpses come to life. It finishes with some interesting observations about the psychological impact of dissecting a dead body as a rite of passage for medical students.

The story is of “a somewhat desultory student” who has been treating the body on which he has been working disrespectfully and is reminded of its humanity as it comes to life. “As a result, he resolves to behave differently in the future”.

The authors of the article, which reprints the story, discuss its modern day relevance for young medical students faced with a dead body they have to cut up.

In some dissecting rooms, even into the twentieth century, the dead were still being treated with irreverence and levity (Smith, 1984).

Today, it is understood that some of these behaviors may result from unresolved tensions. Recent studies by Hafferty (1991), Horne et al. (1990), and Gustavson (1988), have shown that first reactions to the dissecting room and to dissection itself may include faintness, physical symptoms of unease, even flight. Anxiety may be expressed as embarrassment, levity, or bravado.

Coping mechanisms include the bestowal by students of fictitious names or speculative personalities or life stories upon the dead. A curious sort of bond can develop between the student and the “person” of the dead body. The emotional experience contrasts with and supplements students’ efforts to internalize anatomical knowledge. There may evolve a sense of familiarity, contact and intimacy, mixed perhaps with a sense of transgression or guilt, and of obligation.

For those not from the UK, ‘Barts’ refers to St Bartholomew’s Hospital which is the oldest working hospital in Europe and probably best known for being associated with Sherlock Holmes.

The article is open, so you can read it online in full.

Link to ‘Celebrating new year in Bart’s dissecting room’.

December 29, 2014

Why you can live a normal life with half a brain

A few extreme cases show that people can be missing large chunks of their brains with no significant ill-effect – why? Tom Stafford explains what it tells us about the true nature of our grey matter.

How much of our brain do we actually need? A number of stories have appeared in the news in recent months about people with chunks of their brains missing or damaged. These cases tell a story about the mind that goes deeper than their initial shock factor. It isn’t just that we don’t understand how the brain works, but that we may be thinking about it in the entirely wrong way.

Earlier this year, a case was reported of a woman who is missing her cerebellum, a distinct structure found at the back of the brain. By some estimates the human cerebellum contains half the brain cells you have. This isn’t just brain damage – the whole structure is absent. Yet this woman lives a normal life; she graduated from school, got married and had a kid following an uneventful pregnancy and birth. A pretty standard biography for a 24-year-old.

The woman wasn’t completely unaffected – she had suffered from uncertain, clumsy, movements her whole life. But the surprise is how she moves at all, missing a part of the brain that is so fundamental it evolved with the first vertebrates. The sharks that swam when dinosaurs walked the Earth had cerebellums.

This case points to a sad fact about brain science. We don’t often shout about it, but there are large gaps in even our basic understanding of the brain. We can’t agree on the function of even some of the most important brain regions, such as the cerebellum. Rare cases such as this show up that ignorance. Every so often someone walks into a hospital and their brain scan reveals the startling differences we can have inside our heads. Startling differences which may have only small observable effects on our behaviour.

Part of the problem may be our way of thinking. It is natural to see the brain as a piece of naturally selected technology, and in human technology there is often a one-to-one mapping between structure and function. If I have a toaster, the heat is provided by the heating element, the time is controlled by the timer and the popping up is driven by a spring. The case of the missing cerebellum reveals there is no such simple scheme for the brain. Although we love to talk about the brain region for vision, for hunger or for love, there are no such brain regions, because the brain isn’t technology where any function is governed by just one part.

Take another recent case, that of a man who was found to have a tapeworm in his brain. Over four years it burrowed “from one side to the other“, causing a variety of problems such as seizures, memory problems and weird smell sensations. Sounds to me like he got off lightly for having a living thing move through his brain. If the brain worked like most designed technology this wouldn’t be possible. If a worm burrowed from one side of your phone to the other, the gadget would die. Indeed, when an early electromechanical computer malfunctioned in the 1940s, an investigation revealed the problem: a moth trapped in a relay – the first actual case of a computer bug being found.

Part of the explanation for the brain’s apparent resilience is its ‘plasticity’ – an ability to adapt its structure based on experience. But another clue comes from a concept advocated by Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist Gerald Edelman. He noticed that biological functions are often supported by multiple structures – single physical features are coded for by multiple genes, for example, so that knocking out any single gene can’t prevent that feature from developing apparently normally. He called the ability of multiple different structures to support a single function ‘degeneracy’.

And so it is with the brain. The important functions our brain carries out are not farmed out to single distinct brain regions, but instead supported by multiple regions, often in similar but slightly different ways. If one structure breaks down, the others can pick up the slack.

This helps explain why cognitive neuroscientists have such problems working out what different brain regions do. If you try and understand brain areas using a simple one-function-per-region and one-region-per-function rule you’ll never be able to design the experiments needed to unpick the degenerate tangle of structure and function.

The cerebellum is most famous for controlling precise movements, but other areas of the brain such as the basal ganglia and the motor cortex are also intimately involved in moving our bodies. Asking what unique thing each area does may be the wrong question, when they are all contributing to the same thing. Memory is another example of an essential biological function which seems to be supported by multiple brain systems. If you bump into someone you’ve met once before, you might remember that they have a reputation for being nice, remember a specific incident of them being nice, or just retrieve a vague positive feeling about them – all forms of memory which tell you to trust this person, and all supported by different brain areas doing the same job in a slightly different way.

Edelman and his colleague, Joseph Gally, called degeneracy a “ubiquitous biological property … a feature of complexity”, claiming it was an inevitable outcome of natural selection. It explains both why unusual brain conditions are not as catastrophic as they might be, and also why scientists find the brain so confounding to try and understand.

My BBC Future column from before Christmas. The original is here. Thanks to everyone on twitter who chipped in on the plural of cerebellum

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers