Tom Stafford's Blog, page 23

February 14, 2015

Half a century of neuroscience

The Lancet has a good retrospective looking back on the last 50 years of neuroscience, which in some ways, was when the field was born.

The Lancet has a good retrospective looking back on the last 50 years of neuroscience, which in some ways, was when the field was born.

Of course, the brain and nervous system has been the subject of study for hundreds, if not thousands, of years but the concept of a dedicated ‘neuroscience’ is relatively new.

The term ‘neuroscience’ was first used in 1962 by biologist Francis Schmitt who previously referred to the integrated study of mind, brain and behaviour by the somewhat less catchy title “biophysics of the mind”. The first undergraduate degree in neuroscience was offered by Amherst College only in 1973.

The Lancet article, by one of the first generation ‘neuroscientists’ Steven Rose, looks back at how the discipline began in the UK (in a pub, as most things do) and then widens his scope to review how neuroscience has transformed over the last 50 years.

But many of the problems that had beset the early days remain unresolved. Neuroscience may be a singular label, but it embraces a plurality of disciplines. Molecular and cognitive neuroscientists still scarcely speak a common language, and for all the outpouring of data from the huge industry that neuroscience has become, Schmitt’s hoped for bridging theories are still in short supply. At what biological level are mental functions to be understood? For many of the former, reductionism rules and the collapse of mind into brain is rarely challenged—there is even a society for “molecular and cellular cognition”—an elision hardly likely to appeal to the cognitivists who regard higher order mental functions as emergent properties of the brain as a system.

It’s an interesting reflection on how neuroscience has changed over its brief lifespan from one of the people who were there at the start.

Link to ’50 years of neuroscience’ in The Lancet.

February 13, 2015

Spike activity 13-02-2015

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

US Governor proposes that welfare recipients should be drug screened and have negative results as a condition for a payment. A fascinating Washington Post piece looks at past data on similar schemes.

BPS Research Digest launches the PsychCrunch podcast. First episode: evidence-based dating.

The brain, interrupted: neurodevelopment and the pre-term baby. Excellent Nature piece.

Fusion has a great piece on *how* we should worry about artificial intelligence.

“The world’s first hotel staffed entirely by robots is set to open in Japan” reports the International Business Times. Clearly they’ve never visited a Travelodge.

Forbes reports on the ‘coming boom in brain medicines’. Personally, I won’t be holding my breath.

There’s an excellent update on new psychoactive substances and synthetics drugs over at Addiction Inbox.

The Scientific 23 is a great site that interviews scientists and there are lots of cognitive scientists discussing their work.

February 10, 2015

You can’t play 20 questions with nature and win

“You can’t play 20 questions with nature and win” is the title of Allen Newell‘s 1973 paper, a classic in cognitive science. In the paper he confesses that although he sees many excellent psychology experiments, all making undeniable scientific contributions, he can’t imagine them cohering into progress for the field as a whole. He describes the state of psychology as focussed on individual phenomena – mental rotation, chunking in memory, subitizing, etc – studied in a way to resolve binary questions – issues such as nature vs nature, conscious vs unconscious, serial vs parallel processing.

There is, I submit, a view of the scientific endeavor that is implicit (and sometimes explicit) in the picture I have presented above. Science advances by playing twenty questions with nature. The proper tactic is to frame a general question, hopefully binary, that can be attacked experimentally. Having settled that bits-worth, one can proceed to the next. The policy appears optimal – one never risks much, there is feedback from nature at every step, and progress is inevitable. Unfortunately, the questions never seem to be really answered, the strategy does not seem to work.

As I considered the issues raised (single code versus multiple code, continuous versus discrete representation, etc.) I found myself conjuring up this model of the current scientific process in psychology- of phenomena to be explored and their explanation by essentially oppositional concepts. And I couldn’t convince myself that it would add up, even in thirty more years of trying, even if one had another 300 papers of similar, excellent ilk.

His diagnosis for one reason that phenomena can generate an endless excellent papers without endless progress is that people can do the same task in different ways. Lots of experiments dissect how people are doing the task, without constraining sufficiently the things Newell says are essential to predict behaviour (the person’s goals and the structure of the task environment), and thus providing no insight into the ultimate target of investigation, the invariant structure of the mind’s processing mechanisms. As a minimum, we must know the method participants are using, never averaging over different methods, he concludes. But this may not be enough:

That the same human subject can adopt many (radically different) methods for the same basic task, depending on goal, background knowledge, and minor details of payoff structure and task texture\u2014all this\u2014 implies that the “normal” means of science may not suffice.

As a prognosis for how to make real progress in understanding the mind he proposes three possible courses of action:

Develop complete processing models – i.e. simulations which are competent to perform the task and include a specification of the way in which different subfunctions (called ‘methods’ by Newell) are deployed.

Analyse a complex task, completely, ‘to force studies into intimate relation with each other’, the idea being that giving a full account of a single task, any task, will force contradictions between theories of different aspects of the task into the open.

‘One program for many task’ – construct a general purpose system which can perform all mental tasks, in other words an artificial intelligence.

It was this last strategy which preoccupied a lot of Newell’s subsequent attention. He developed a general problem solving architecture he called SOAR, which he presented as a unified theory of cognition, and which he worked on until his death in 1992.

The paper is over forty years old, but still full of useful thoughts for anyone interested in the sciences of the mind.

Reference and link:

Newell, A. You can’t play 20 questions with nature and win: Projective comments on the papers of this symposium. in Chase, W. G. (Ed.). (1973). Visual Information Processing: Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Carnegie Symposium on Cognition, Held at the Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, May 19, 1972. Academic Press.

See a nice picture of Newell from the Computer History Museum

February 3, 2015

What gambling monkeys teach us about human rationality

We often make stupid choices when gambling, says Tom Stafford, but if you look at how monkeys act in the same situation, maybe there’s good reason.

When we gamble, something odd and seemingly irrational happens.

It’s called the ‘hot hand’ fallacy – a belief that your luck comes in streaks – and it can lose you a lot of money. Win on roulette and your chances of winning again aren’t more or less – they stay exactly the same. But something in human psychology resists this fact, and people often place money on the premise that streaks of luck will continue – the so called ‘hot hand’.

The opposite superstition is to bet that a streak has to end, in the false belief that independent events of chance must somehow even out. This is known as the gambler’s fallacy, and achieved notoriety at the Casino de Monte-Carlo on 18 August 1913. The ball fell on black 26 times in a row, and as the streak lengthened gamblers lost millions betting on red, believing that the chances changed with the length of the run of blacks.

Why do people act this way time and time again? We can discover intriguing insights, it seems, by recruiting monkeys and getting them to gamble too. If these animals make dumb choices like us, perhaps it could tell us more about ourselves.

First though, let’s look at what makes some games particularly likely to trigger these effects. Many results in games are based on a skill element, so it makes reasonable sense to bet, for instance, that a top striker like Lionel Messi is more likely to score a goal than a low-scoring defender.

Yet plenty of games contain randomness. For truly random events like roulette or the lottery, there is no force which makes clumps more or less likely to continue. Consider coin tosses: if you have tossed 10 heads in a row your chance of throwing another heads is still 50:50 (although, of course, at the point before you’ve thrown any, the overall odds of throwing 10 in a row is still minuscule).

The hot hand and gambler’s fallacies both show that we tend to have an unreasonable faith in the non-randomness of the universe, as if we can’t quite believe that those coins (or roulette wheels, or playing cards) really are due to the same chances on each flip, spin or deal.

It’s a result that sometimes makes us sneer at the irrationality of human psychology. But that conclusion may need revising.

Cross-species gambling

An experiment reported by Tommy Blanchard of the University of Rochester in New York State, and colleagues, shows that monkeys playing a gambling game are swayed by the same hot hand bias as humans. Their experiments involved three monkeys controlling a computer display with their eye-movements – indicating their choices by shifting their gaze left or right. In the experiment they were given two options, only one of which delivered a reward. When the correct option was random – the same 50:50 chance as a coin flip – the monkeys still had a tendency to select the previously winning option, as if luck should continue, clumping together in streaks.

The reason the result is so interesting is that monkeys aren’t taught probability theory as school. They never learn theories of randomness, or pick up complex ideas about chance events. The monkey’s choices must be based on some more primitive instincts about how the world works – they can’t be displaying irrational beliefs about probability, because they cannot have false beliefs, in the way humans can, about how luck works. Yet they show the same bias.

What’s going on, the researchers argue, is that it’s usually beneficial to behave in this manner. In most of life, chains of success or failure are linked for good reason – some days you really do have your eye on your tennis serve, or everything goes wrong with your car on the same day because the mechanics of the parts are connected. In these cases, the events reflect an underlying reality, and one you can take advantage of to predict what happens next. An example that works well for the monkeys is food. Finding high-value morsels like ripe food is a chance event, but also one where each instance isn’t independent. If you find one fruit on a tree the chances are that you’ll find more.

The wider lesson for students of human nature is that we shouldn’t be quick to call behaviours irrational. Sure, belief in the hot hand might make you bet wrong on a series of coin flips, or worse, lose a pot of money. But it may be that across the timespan in evolution, thinking that luck comes in clumps turned out to be useful more often than it was harmful.

This is my BBC Future article from last week. The original is here

February 1, 2015

A refocus of military influence

The British media has been covering the creation of 77th Brigade, or ‘Chindits’ in the UK Army which they’ve wrongly described as PsyOps ‘Twitter troops’. The renaming is new but the plan for a significant restructuring and expansion of the UK military’s influence operations is not.

The British media has been covering the creation of 77th Brigade, or ‘Chindits’ in the UK Army which they’ve wrongly described as PsyOps ‘Twitter troops’. The renaming is new but the plan for a significant restructuring and expansion of the UK military’s influence operations is not.

The change in focus has been prompted by a growing realisation that the success of security strategy depends as much on influencing populations at home and abroad as it does through military force.

The creation of a new military structure, designed to tackle exactly this problem, was actually reported last year in British Army 2014 – a glossy annual policy publication. The latest announcement of the 77th Brigade is really just a media-friendly re-branding of the existing plan.

You can read the document online (warning it’s a 50Mb plus pdf) but here’s a crucial section from page 121 onwards:

Our potential adversaries and partners are increasingly blurring the lines between regular and irregular and between military, political, economic and information activities. At least three nations who operate large conventional ‘traditional’ armies have now also adopted the Chinese concept of Unrestricted Warfare.

Author Steve Metz describes this as involving “diverse, simultaneous attacks on an adversary’s social, economic and political systems. It ignores and transcends the ‘boundaries the boundaries between what is a weapon and what is not, between soldier and non-combatant, between state and non-state or suprastate.” If we wish to succeed in such as environment we need to compete on an equal footing.

To do this, we must change not only our physical capabilities but our conceptual approach, our planning and our execution. This is not to say that the virtual and cognitive domains now produce a ‘silver bullet’ that will mean the end of combat, but that “superiority in the physical environment was of little value unless it could be translated into an advantage in the information environment”…

In order to shift the Army’s thinking in the approach to this new manoeuvre, the Security Assistance Group (SAG) will form in September 2014. It will form through the amalgamation of the current 15 Psychological Operations Group, the Military Stabilisation Support Group, the Media Operations Group and the Security Capacity Team.

However, these structures are merely the start point for a fully integrated capability that will harness a wide range of powers to achieve the desired effects – from cyber through to engagement, commercial, financial, stabilisation and deception. At the heart of the new structure must be a culture and attitude that is both Defence and civilian orientated.

And that is really what the ‘newly announced’ 77th Brigade is all about.

To see how seriously the British Army are taking this, the 77th is reportedly going to be made up of up to 2,000 full-time and reserve troops. Think Defence report that the combined strength of all the existing relevant groups that will be incorporated is just 300 people.

The idea is to make Information Operations a much more central part of military doctrine. This includes electronic warfare and computer hacking, physical force targeted on information resources (like taking out infrastructure), psychological operations – traditionally focused on changing belief and behaviour in the theatre of war, media operations – essentially corporate PR, and a wider use of media to influence external populations and potential adversaries.

The Daily Express reports that “the brigade will bring together specialists in media, signalling and psychological operations, with some Special Forces soldiers and possibly computer hackers” which seems likely to reflect exactly what the Army are aiming for in their new plan.

From this point of view, you can see why governments are so keen to hold on to their Snowden-era digital monitoring and intervention capabilities.

They typically justify their existence in terms of ‘breaking terrorist networks’ but they are equally as useful for their role in wider information operations – targeting groups rather than individuals – now considered key to national security.

The formation of the 77th Brigade is a mostly reflection of a wider refiguring of global conflict that puts cognition and behaviour at the centre of political objectives.

It is simultaneously more and less democratic that ‘hard power’. It makes the battle of ideas, rather than the use of force, central to determining political outcome but attempts to shape the information environment so some ideas become more equal than others.

January 31, 2015

Spike activity 30-01-2015

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

PLOS Neuroscience has an excellent interview on the strengths and limitations of fMRI.

There’s an excellent profile of clinical psychologist Andrea Letamendi and her interest in comics and mental health in The Atlantic.

The Wall Street Journal has an excellent piece on hikikomori – a syndrome of ultra withdrawal by Japanese youth.

The Hearing Voices Network as an alternative approach to supporting voice hearers is covered by a good article in The Independent.

Backchannel looks at the largest ‘virtual psychology lab’ in the world.

Does subliminal advertising actually work? asks BBC News.

BPS Research Digest covers a study finding that psychologists and psychiatrists rate patients less positively when their problems are explained biologically. Along the lines of several similar studies.

In the 21st Century, project management for parents

I’ve just read an excellent book on the surprising anomaly of modern parenting called All Joy and No Fun.

I’ve just read an excellent book on the surprising anomaly of modern parenting called All Joy and No Fun.

It’s by the writer Jennifer Senior who we’ve featured a few times on Mind Hacks for her insightful pieces on the social mind.

In All Joy and No Fun she looks at how the modern model of childhood born after the Second World War – “long and sheltered, devoted almost entirely to education and emotional growth” – has begun to mutate in some quarters into an all consuming occupation of over-parenting that has meant childcare has been consistently rated as one of the least enjoyable family activities in a wide range of studies.

The book combines field trips with parenting in middle American (YMMV) and a look at the surprising data about how parenting has become almost a competitive sport which requires forever more money, time, restrictions and plans, lest you be accused be being a ‘bad parent’.

New parents in the United States, Mead observes, are willing to try almost any new fad or craze for their baby’s sake. “We find new schools of education, new schools of diet, new schools of human relations… And we find serious, educated people following their dictates.” Which is why attachment parenting is consdiered de rigeur one year and overbearing three years later. And why cry-it-out is all the rage one moment and then, after a couple of seasons, considered cruel. And why organic home-milled purees suddenly supplant jars of Gerber’s, though an entire generation has done just fine on Gerber’s and even gone on to write books, run companies and do Nobel-winning science. Uncertainty is why parents buy Baby Einstein products, though there’s no evidence that they do anything to alter the cognitive trajectory of a child’s life, and explains why a friend – an extremely bright and reasonable man – asked me, with the straightest of faces and finest of intentions, why I wasn’t teaching my son sign language when he was small.

Because he was writing in the 1950s, psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott talked about the ‘good enough mother’, but taking its more modern version, we could say that ‘good enough parenting’ is all that parents need to aspire to.

All Joy and No Fun is a thought-provoking exploration of how childrearing become so unenjoyable in the 21st Century, and how fads, fashions and commerce, seek to undermine ‘good enough parenting’.

Link to more details on All Joy and No Fun.

January 30, 2015

Hard Problem defeats legendary playwright

I’ve written a review of legendary playwright Tom Stoppard’s new play The Hard Problem at the National Theatre, where he tackles neuroscience and consciousness – or at least thinks he does.

The review is in The Psychologist and covers the themes running through Stoppard’s new work and how they combine with the subtly misfiring conceptualisation of cognitive science:

This is a typical and often pedantic criticism of plays about technical subjects but in Stoppard’s case, the work is primarily about what defines us as human, in light of the science of human nature, and because of this, the material often comes off as clunky. It’s not that the descriptions are inaccurate – allusions to optogenetics, Gödel and the computability of consciousness, game theory, and cortisol studies of risk in poker players, are all in context – but Stoppard doesn’t really understand what implications these concept have for either each other or for his main contention. Questions about mind and body, consciousness and morality, are confused at times, and it’s not clear that Stoppard really understands the true implications of the Hard Problem of consciousness.

It’s worth saying, I actually enjoyed the play, but it was Stoppard’s philosophy and unwieldy use of neuroscience that didn’t quite hang together for me.

The full piece is the link below.

Link to review of The Hard Problem in The Psycholgist

January 24, 2015

A misdiagnosis of trauma in Ancient Babylon

Despite the news reports, researchers probably haven’t discovered a mention of ‘PTSD’ from 1300BC Mesopotamia. The claim is likely due to a rather rough interpretation of Ancient Babylonian texts but it also reflects a curious interest in trying to find modern psychiatric diagnoses in the past, which tells us more about our own clinical insecurities than the psychology of the ancient world.

Despite the news reports, researchers probably haven’t discovered a mention of ‘PTSD’ from 1300BC Mesopotamia. The claim is likely due to a rather rough interpretation of Ancient Babylonian texts but it also reflects a curious interest in trying to find modern psychiatric diagnoses in the past, which tells us more about our own clinical insecurities than the psychology of the ancient world.

The claim comes from a new article published in Early Science and Medicine and it turns out there’s a pdf of the article available online if you want to read it in full.

The authors cite some passages from Babylonian medical texts in support of the fact that ‘symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder’ were recorded in soldiers. Here are the key translated passages from the article:

14.34 “If his words are unintelligible for three days […] his mouth [F…] and he experiences wandering about for three days in a row F…1.”

14.35 “He experiences wandering about (for three) consecutive (days)”; this means: “he experiences alteration of mentation (for three) consecutive (days).”

14.36 “If his words are unintelligible and depression keeps falling on him at regular intervals (and he has been sick) for three days F…]”

19.32 “If in the evening, he sees either a living person or a dead person or someone known to him or someone not known to him or anybody or anything and becomes afraid; he turns around but, like one who has [been hexed with?] rancid oil, his mouth is seized so that he is unable to cry out to one who sleeps next to him, ‘hand’ of ghost (var. hand of […]).”

19.33 “[If] his mentation is altered so that he is not in full possession of his faculties, ‘hand’ of a roving ghost; he will die.”

19.34 “If his mentation is altered, […] (and) forgetfulness(?) (and) his words hinder each other in his mouth, a roaming ghost afflicts him. (If) […], he will get well.”

Firstly, it’s clearly a huge stretch to suggest these are symptoms of PTSD which is defined as groupings of intrusive memories of the traumatising event, heightened arousal or emotional numbing, avoidance of reminders and, since the DSM-5, depression-like symptoms.

The authors suggest that the strongest evidence for the fact that the ancient descriptions are PTSD is that the ‘ghost’ mentioned in the text is often considered to be the ghosts of enemies whom the patient killed during military operations, and these could be PTSD-like flashbacks.

The trouble is that ‘ghosts’ are given as causes of many disorders in Babylonian medicine. Furthermore, all of the symptoms the authors describe could clearly also describe epilepsy and, in fact, are described in Babylonian texts on epilepsy.

For example, these are all symptoms described in BM 47753 a Babylonian tablet on epilepsy, discussed a 1990 article, that also describes wandering, confusion and unintelligible speech.

If he keeps going into and out of (his house) or getting into and out of his clothes .. or talks unintelligibly a great deal, does not any more eat his bread and beer rations and does not go to bed…

If, in a state of fear, he keeps getting up and sitting down, (or) if he mutters unintelligibly a great deal and becomes more and more restless…

Most symptoms are diagnosed as a form of being touched by the hand of a supernatural being. Below are some ‘ghost’ afflictions that are clearly epilepsy related, including ‘ghosts’ who have died violently in various ways, including a ‘mass killing’.

If at the end of his fit his limbs become paralysed, he is dazed (or, dizzy), his abdomen is “wasted” (sc., as of one in need of food) and he returns everything which is put into his mouth …….-hand of a ghost who has died in a mass killing.

If when his limbs become at rest again like those of a healthy person his mouth is seized so that he cannot speak,-hand of the ghost of a murderer. R: hand of the ghost of a person burned to death in a fire.

If when his limbs become at rest again like those of a healthy person he remains silent and does not eat anything,-hand of the ghost of a murderer; alternatively, hand of the ghost of a person burned to death in a fire

Oddly, the authors of the ‘ancient PTSD’ article suggest that references to slurring of speech and cognitive difficulties might reflect co-morbid drug abuse. They also admit that all their cited symptoms could be caused by head injury but as prognosis is given as non-fatal, they were probably PTSD-related. But again, epilepsy seems a much better fit here both from a contemporary and Babylonian perspective.

In fact, historians Kinnier Wilson and Reynolds, who wrote the 1990 article on Babylonian epilepsy texts, were quite convinced that references to ‘ghosts’ were ancient terms for nocturnal epilepsy, not ‘flashbacks’.

But it’s also worth mentioning that the ‘ancient PTSD’ argument is in a long-line of studies that attempt to match contemporary psychiatric diagnoses to vague historical references as a way of legitimising the modern concepts.

However, the ways in which psychological distress, particularly trauma, is expressed are massively affected by culture. PTSD is unlikely to be a concept that transcends time, place and social structure.

In fact, historians have not been able to convincingly find any PTSD-like descriptions in history and there seems a virtually complete absence of any records of flashbacks in the medical records of First and Second World War veterans, let alone in Ancient Babylon.

War, violence and tragedy has left its psychological mark on individuals from the beginning of time.

PTSD is a useful diagnosis we’ve created to help us deal with some of the consequences of these awful events in the limited but important contexts in which it occurs – but it’s not a universal feature of human nature.

Who knows whether anything like PTSD existed for the Babylonians but the fact that we can use it to help people is all we need to legitimise it.

January 22, 2015

From the machine

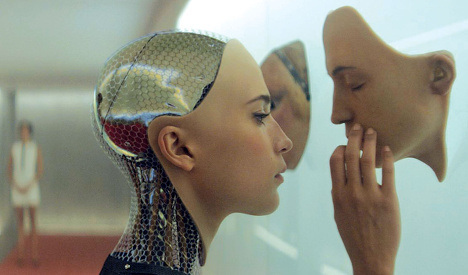

A new film, Ex Machina, is released in the UK tomorrow and it is quite possibly one of the best sci-fi films of recent times and probably the best film about consciousness and artificial intelligence ever made.

The movie revolves around startup geek turned tech corp billionaire Nathan who has created the artificially conscious android Ava. Nathan invites one of his corporate coders, Caleb, to help test whether Ava feels conscious.

The film is near-future but in the tradition of sci-fi as a theatre in which to test ideas, it focuses on the stark and unexpected issues raised by self-conscious robots designed for the human market.

Writer and debut director Alex Garland clearly put a lot of effort into getting the scientific concepts right, enlisting biologist Adam Rutherford and cognitive roboticist Murray Shanahan to finesse the philosophy of mind.

In addition, it’s brilliantly acted, paranoid, subtly disturbing and thought-provoking – long after the credits roll.

It’s also sparked some great reviews of the movie and the cognitive science behind it. The Independent has an excellent piece on the science behind the plot and there’s a great interview with the scientific advisors in Dazed.

But probably the best so far is consciousness researcher Anil Seth’s extended review in New Scientist which tackles the core of the film’s philosophical kick:

While the Turing test has provided a trope for many AI-inspired movies… Ex Machina takes things much further. In a sparkling exchange between Caleb and Nathan, Garland nails the weakness of Turing’s version of the test, a focus on the disembodied exchange of messages, and proposes something far more interesting. “The challenge is to show you that she’s a robot. And see if you still feel she has consciousness,” Nathan says to Caleb.

This shifts the goalposts in a vital way. What matters is not whether Ava is a machine. It is not even whether Ava, even though a machine, can be conscious. What matters is whether Ava makes a conscious person feel that Ava is conscious. The brilliance of Ex Machina is that it reveals the Turing test for what it really is: a test of the human, not of the machine. And Garland is not necessarily on our side.

In fact, the film constantly flips viewers between thinking of Ava as a machine, and as a conscious being, and forces us to constantly check the shifting plot reality to see if it still holds together.

At the end of the film you come to realise that it’s not Ava who’s being tested, it’s you.

Link to Ex Machina page on Wikipedia.

Link to trailer on YouTube.

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers