Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 124

July 26, 2011

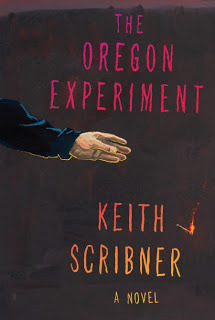

Keith Scribner talks about professional noses and The Oregon Experiment

Keith Scribner'

s third novel The Oregon Experiment is irresistible. Trust me. His two previous novels include The GoodLife and Miracle Girl. The GoodLife appears in translation, was selected for the Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers series, and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. I loved The Oregon Experiment and am thrilled Keith agreed to let me pepper him with questions. Thank you, Keith!I love the fact that you have a professional "nose" in the book. That brilliant element did what the best works of literature do--it made me see and feel and experience the world differently. So tell me about the research you did for this. What did you find that surprised you?"

Keith Scribner'

s third novel The Oregon Experiment is irresistible. Trust me. His two previous novels include The GoodLife and Miracle Girl. The GoodLife appears in translation, was selected for the Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers series, and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. I loved The Oregon Experiment and am thrilled Keith agreed to let me pepper him with questions. Thank you, Keith!I love the fact that you have a professional "nose" in the book. That brilliant element did what the best works of literature do--it made me see and feel and experience the world differently. So tell me about the research you did for this. What did you find that surprised you?"I read at least 8 or 10 books about the nose and how we smell, about perfume making, and about anosmia. Then I was very lucky to be introduced to a perfume maker in San Francisco, Yosh Han. She invited me to her studio and I spent the day making (with her help) the perfume that Naomi is trying to make in the book. It was really fun, intoxicating, fascinating. She lined up all her nastiest smelling Northwest essences to make the frog juice. I told her about the frog and the auto body putty. As I describe in the novel, it's a process of selecting then editing. Although many perfumiers use dipsticks (as Naomi does in the novel), Yosh lines the vials up on her worktable and sniffs them in order from base notes to top, then back down. In one long breath, you try to take in the full essence. Just this week I wrote a blog on this subject for Powell's Books.

I think what surprised me most was to learn how many people never think about smells and claim they can't smell at all, AND that people for whom smell is important (like Naomi) who lose it are so completely devastated. Also, that the relationship between smells and tastes is even closer than I'd thought, and that certain things, like basil and mint, are actually more smell than taste although we perceive them as tastes.

I also adored the whole secessionist movement in the novel. It seemed both divinely inspired and highly plausible at the same time. Where did this come from?

There's a long and continuing tradition of secessionism in Oregon and the Northwest generally. And as you say, its plausibility--the fact that the arguments for it are so sensible--yet the fact that it's so unlikely made it appealing to me. All my characters are idealists--or at least are struggling between their ideals and the realities of the world--so a very unlikely yet plausible movement seemed like an enterprise they should be involved in. Secession also acts metaphorically throughout the book--Scanlon and Naomi separating themselves from the east coast, Sequoia separating herself from her father and her past; the secessionist movement for her is both deeply personal and political. The rejection of the patriarchy for all the characters is alive in both the personal and political.

In general, secession, or moving from a state of union to separateness, is all over the book. I'm sure you know the experience of latching on to an idea like this and then seeing it in everything.

The writing is so dazzling, and the plotting so assured. What's your writing process like?

When I started the novel--for about the first two years of writing--it was all in Scanlon's point of view. As the characters of Naomi, Sequioa, and Clay came to life for me, I was too constrained just staying with Scanlon. As the story opened out, the points of view had to, too. One thing that helps me with plotting is that I note each scene on a card after I've written it and stick it up on a bulletin board. I usually start the board going when I hit about page 100 of a novel, which is the point at which I begin to have trouble keeping the whole thing in my head. With the note cards, I can see in a glance what follows what; I can move scenes around; I can pull something out and see all the implications. I'm not sure I could write a novel without this big visual representation of the structure, especially when I'm nearing the end and it's so hard to hold the entire thing in my head at once.

As for dazzling writing--thank you. All I can say is it's hundreds of passes over every sentence, many of those reading aloud so I can hear the language. And my phenomenal editor Gary Fisketjon deserves a nod, too--from big picture elements of plot and theme to his line-level genius, he's as good as they get.

What's obsessing you now?

My new novel is set partly in Oregon but mostly in Connecticut. As you might know, Connecticut shade and broadleaf tobacco are the best cigar wrappers in the world. When I was a kid, growing up in East Granby, Conn, lots of my friends worked tobacco. (I didn't; there was a truck farm near my house where I worked.) Shade tobacco is grown under cheesecloth nets (now synthetic). Local kids and migrant workers have worked the fields since the late nineteenth century. For now, the novel is set in the 1970s as well as the present, and I've become obsessed with researching the delicate process of growing, picking, and drying the very valuable leaves. I think tobacco will be for this novel what perfume and scents are for THE OREGON EXPERIMENT. I've made contact with a tobacco buyer who's going to get me under the nets this summer or next. And I aim to enjoy a cigar before I'm done writing the book. So far, I love the smell of cigar smoke from a distance, but smoking one makes me a little sick.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

Let's see....Since smells can be the most direct path to memory, in a novel that's so much about how our pasts can define us and haunt us, the emphasis on smell worked to my advantage.

Related to this, I'm interested in how each character engages the world differently--Naomi's engagement is mostly sensuous, through her nose, and in this way she acts primally. Clay too acts primally, and instinctively. Sequoia engages the world through her body; Scanlon is motivated cerebrally and also by ego. Although I began with much neater ideas about each character in this regard (and they became complicated in the writing), they each do engage the world in different ways, which helps to define them, lead to conflict, misunderstanding, trouble in general and, I hope, the different perspectives that are one of the pleasures of a polyphonic novel.

Published on July 26, 2011 14:23

July 24, 2011

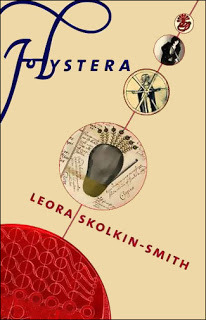

Leora Skolkin-Smith and Jessica Brilliant Keener talk about the brave new world of publishing and the Fiction Studio Imprint

Welcome to publishing not as usual!

The Fiction Studio Imprint is the brain child of New York Times bestselling author, former publisher of Avon Books and Berkley Books, Lou Aronica. An invitation only imprint, The Fiction Studio publishes books in paperback and e-book format and it represents a revolutionary new way of publishing. Aronica,created this new frontier, a gathering of "ambitious wildly creative writers." To read the whole story, look here.

I have Lou coming on here later, but in the meantime, I wanted to talk to two of the writers who were invited to this imprint.

Leora Skolkin-Smith's first book The Fragile Mistress is about to launch as a feature film from Triboro Films and her second novel Hystera will be published by the Fiction Studio. The Fragile Mistress was nominated for the 2006 Pen/Faulkner Award and the Pen/Ernest Hemingway Award by Grace Paley. It was a National women Studies Association Conference Selection, A Bloomsbury Review Pick and a Jewish Book Council Selection.

Jessica Keenerr's novel Night Swim will be published by the Fiction Studio. Jessica writes for The Boston Globe, and reads fiction for Agni. Her work has appeared in O: The Oprah Magazine, Poets & Writers and more, and her business memoir, Time to Make the Donuts, continues to sell. Jessica's fiction has been listed in the Pushcart Prize under "100 Outstanding Writers," and excerpts from Night Swim have been published in MiPoesias, Eclectica Magazine, Night Train and Wilderness House Literary Review, which awarded her with a Chekhov Prize for Excellence in Fiction. Another excerpt from Night Swim was awarded a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant in fiction.

Both are extraordinary writers and both agreed to have a conversation about Fiction Studio for my blog. Thank you, Leora and Jessica!

Jessica: So why the Fiction Studio for you?

Leora: I think, for me, Lou's acceptance gave me a certain freedom, that is I could finally write and not have to hustle and please editors I knew I couldn't. It took the hopelessness away, all that anguished activity which had to with trying to fit into some a priori model in which I felt estranged.I didn't have to write to please, or be a writer for hire. I had some older European tradition in my soul. I honestly wanted to write find out who I was, what meaning I could bring to fiction. Pretentious, right?

Jessica: Leora-I'm there with you and your old, European soul. When I finally took this leap to go with Lou and publish Night Swim, I felt freed (at last), all my internal blocks pulverized. But it definitely took some time to get there. (How about years?) I continue to feel more joyous everyday. I love this sensation of regaining control. I love knowing that I can leap after wild marketing ideas and pursue them without waiting for so many layers of approval. Lou is super easy and responsive and has a steady demeanor. Also, over the past decade, I've seen what's been happening to so many fantastic writers--writers whose stories haunt, disturb and inspire--yet these writers were getting turned away (and still are). It was more than just sad or disappointing for myself and for others, it started to feel wrong, like the balance--in the old Shakespearean sense--was out of whack.

Suddenly, the world of fiction and literary arts is open again. There's a party and neighborhood for all kinds of writers and readers, and a way to bring variety back into books. This is what I find most exciting. Writers and readers can't all squeeze through one door.

Leora: Jessica, this is so reassuring, I think one of the things that happened to me was a sense of such utter alienation..and what's so great is people understanding, feeling the same way, self-affirmation but also a affirmation in a community. I'm happier, too, and able to write, just write. And yes, the taking back of control was crucial.

My experience with "regular publishing" was this internal sense of not being able to please, to be excluded among the "chosen", like a mark across the forehead, a curse of some devil phantom because at 59, I'm way past trying just to make an editor believe in my work, I had developed my own inner laboratory and did not want to just get "hired" to dazzle. I couldn't dazzle. I'm serious and my work is trying on the nervous system of a reader, and then (here's the fatal blow) I'm very" intellectual." I love literature as much as I love trying to write it and have learned so much when wonderful editors gave me the chance to write literary criticism...still, another part of me was self-lacerating when I couldn't "dazzle" and I started to internalize all the alienation, and I had to walk around with this armload of anger. Sometimes even rage. I began to feel hopeless in this era of publishing. Was my life as a writer reduced now to just making a young editor go "Wow, I love it!" I didn't want that, essentially, for myself or my work. It felt humiliating, a bit degrading, or at the very least, counter to my own desires as a writer. Writing well was about taking the risk of being disturbing, not pleasing, shaking the world up a bit, exploring the dark and mysterious and yet it seemed the publishing business was so intent on this one-dimensional "Wow, I love it!" .Lou's acceptance was different.

What attracted to me to Lou's imprint was Lou. He has a quiet and accepting manner and he's a real businessman, a real publisher. It was fascinating to talk to him and hear his long experiences with publishing, how he saw the new world of e-books, how he viewed the whole world of publishing, a veteran was talking to me, a person of substantial experience. I got the feeling I was with the real thing in the sense of a real publisher in the old school way, an entrepreneur, excited about his business and what he could do in his field, he made me feel as energetic and hopeful.

Now, well, I'm feeling free. I started a new book and I don't feel the old demons tugging at me,( that is the demons of "I HAVE to make sales and show someone I can be a profit-earning player." ) I'm a writer again, my only demons are mine. I'm only haunted by my own images and stories. Whether I'm good or bad, is not as important as the simple fact that I AM.

Jessica: This is my debut novel, so this is a huge time for me, a breakthrough after years--dare I tell you it's been decades--of frustration. I've been represented by top agents at top agencies and earlier novels have made the rounds with no "luck" or whatever you want to call it, though I've gotten writing grants, awards, honors and all those good things. So, the obvious answer is that my experience trying to get a novel published basically sucked. I co-published a business memoir and that went well, actually. I wrote a proposal and sold it in two weeks, then supported myself on the advance I got. I wrote that book in nine months. The book (Time to Make the Donuts) is still selling. The hardcover sold out and it's available now on Kindle. But, finding a publisher for my novel was a completely different, totally unrequited experience.

I sent Lou Night Swim and a mere two weeks later I got and email saying he loved it and wanted to publish it. We talked on the phone the next day. I was thrilled, but a nagging part of me still hesitated, still holding out internally for the old way--the way of my other book. But, my dad had recently died, and everything felt intense. I saw time passing so quickly. It scared me. Still, I held off for almost four months. Yet, I liked Lou immensely. He's easy to talk to. He's calm. He's a veteran. An editor and a writer. I feel I can be myself, and that, in my opinion, is golden. I also liked that he was particular about what gets published by Fiction Studio Books. This wasn't a free-for-all publication venture. Quality matters to Lou, and it matters to me.

I'm a debut novelist, and right now everything feels wonderful,exciting and liberating. I'm going through copy edits. Next up, is my book cover. Every step feels new and affirming. I find myself smiling a lot and when people congratulate me and share in my joy, it's a gracious sensation. I love that Lou wants to support what I love doing, and that I have this opportunity, at long last.

The Fiction Studio Imprint is the brain child of New York Times bestselling author, former publisher of Avon Books and Berkley Books, Lou Aronica. An invitation only imprint, The Fiction Studio publishes books in paperback and e-book format and it represents a revolutionary new way of publishing. Aronica,created this new frontier, a gathering of "ambitious wildly creative writers." To read the whole story, look here.

I have Lou coming on here later, but in the meantime, I wanted to talk to two of the writers who were invited to this imprint.

Leora Skolkin-Smith's first book The Fragile Mistress is about to launch as a feature film from Triboro Films and her second novel Hystera will be published by the Fiction Studio. The Fragile Mistress was nominated for the 2006 Pen/Faulkner Award and the Pen/Ernest Hemingway Award by Grace Paley. It was a National women Studies Association Conference Selection, A Bloomsbury Review Pick and a Jewish Book Council Selection.

Jessica Keenerr's novel Night Swim will be published by the Fiction Studio. Jessica writes for The Boston Globe, and reads fiction for Agni. Her work has appeared in O: The Oprah Magazine, Poets & Writers and more, and her business memoir, Time to Make the Donuts, continues to sell. Jessica's fiction has been listed in the Pushcart Prize under "100 Outstanding Writers," and excerpts from Night Swim have been published in MiPoesias, Eclectica Magazine, Night Train and Wilderness House Literary Review, which awarded her with a Chekhov Prize for Excellence in Fiction. Another excerpt from Night Swim was awarded a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant in fiction.

Both are extraordinary writers and both agreed to have a conversation about Fiction Studio for my blog. Thank you, Leora and Jessica!

Jessica: So why the Fiction Studio for you?

Leora: I think, for me, Lou's acceptance gave me a certain freedom, that is I could finally write and not have to hustle and please editors I knew I couldn't. It took the hopelessness away, all that anguished activity which had to with trying to fit into some a priori model in which I felt estranged.I didn't have to write to please, or be a writer for hire. I had some older European tradition in my soul. I honestly wanted to write find out who I was, what meaning I could bring to fiction. Pretentious, right?

Jessica: Leora-I'm there with you and your old, European soul. When I finally took this leap to go with Lou and publish Night Swim, I felt freed (at last), all my internal blocks pulverized. But it definitely took some time to get there. (How about years?) I continue to feel more joyous everyday. I love this sensation of regaining control. I love knowing that I can leap after wild marketing ideas and pursue them without waiting for so many layers of approval. Lou is super easy and responsive and has a steady demeanor. Also, over the past decade, I've seen what's been happening to so many fantastic writers--writers whose stories haunt, disturb and inspire--yet these writers were getting turned away (and still are). It was more than just sad or disappointing for myself and for others, it started to feel wrong, like the balance--in the old Shakespearean sense--was out of whack.

Suddenly, the world of fiction and literary arts is open again. There's a party and neighborhood for all kinds of writers and readers, and a way to bring variety back into books. This is what I find most exciting. Writers and readers can't all squeeze through one door.

Leora: Jessica, this is so reassuring, I think one of the things that happened to me was a sense of such utter alienation..and what's so great is people understanding, feeling the same way, self-affirmation but also a affirmation in a community. I'm happier, too, and able to write, just write. And yes, the taking back of control was crucial.

My experience with "regular publishing" was this internal sense of not being able to please, to be excluded among the "chosen", like a mark across the forehead, a curse of some devil phantom because at 59, I'm way past trying just to make an editor believe in my work, I had developed my own inner laboratory and did not want to just get "hired" to dazzle. I couldn't dazzle. I'm serious and my work is trying on the nervous system of a reader, and then (here's the fatal blow) I'm very" intellectual." I love literature as much as I love trying to write it and have learned so much when wonderful editors gave me the chance to write literary criticism...still, another part of me was self-lacerating when I couldn't "dazzle" and I started to internalize all the alienation, and I had to walk around with this armload of anger. Sometimes even rage. I began to feel hopeless in this era of publishing. Was my life as a writer reduced now to just making a young editor go "Wow, I love it!" I didn't want that, essentially, for myself or my work. It felt humiliating, a bit degrading, or at the very least, counter to my own desires as a writer. Writing well was about taking the risk of being disturbing, not pleasing, shaking the world up a bit, exploring the dark and mysterious and yet it seemed the publishing business was so intent on this one-dimensional "Wow, I love it!" .Lou's acceptance was different.

What attracted to me to Lou's imprint was Lou. He has a quiet and accepting manner and he's a real businessman, a real publisher. It was fascinating to talk to him and hear his long experiences with publishing, how he saw the new world of e-books, how he viewed the whole world of publishing, a veteran was talking to me, a person of substantial experience. I got the feeling I was with the real thing in the sense of a real publisher in the old school way, an entrepreneur, excited about his business and what he could do in his field, he made me feel as energetic and hopeful.

Now, well, I'm feeling free. I started a new book and I don't feel the old demons tugging at me,( that is the demons of "I HAVE to make sales and show someone I can be a profit-earning player." ) I'm a writer again, my only demons are mine. I'm only haunted by my own images and stories. Whether I'm good or bad, is not as important as the simple fact that I AM.

Jessica: This is my debut novel, so this is a huge time for me, a breakthrough after years--dare I tell you it's been decades--of frustration. I've been represented by top agents at top agencies and earlier novels have made the rounds with no "luck" or whatever you want to call it, though I've gotten writing grants, awards, honors and all those good things. So, the obvious answer is that my experience trying to get a novel published basically sucked. I co-published a business memoir and that went well, actually. I wrote a proposal and sold it in two weeks, then supported myself on the advance I got. I wrote that book in nine months. The book (Time to Make the Donuts) is still selling. The hardcover sold out and it's available now on Kindle. But, finding a publisher for my novel was a completely different, totally unrequited experience.

I sent Lou Night Swim and a mere two weeks later I got and email saying he loved it and wanted to publish it. We talked on the phone the next day. I was thrilled, but a nagging part of me still hesitated, still holding out internally for the old way--the way of my other book. But, my dad had recently died, and everything felt intense. I saw time passing so quickly. It scared me. Still, I held off for almost four months. Yet, I liked Lou immensely. He's easy to talk to. He's calm. He's a veteran. An editor and a writer. I feel I can be myself, and that, in my opinion, is golden. I also liked that he was particular about what gets published by Fiction Studio Books. This wasn't a free-for-all publication venture. Quality matters to Lou, and it matters to me.

I'm a debut novelist, and right now everything feels wonderful,exciting and liberating. I'm going through copy edits. Next up, is my book cover. Every step feels new and affirming. I find myself smiling a lot and when people congratulate me and share in my joy, it's a gracious sensation. I love that Lou wants to support what I love doing, and that I have this opportunity, at long last.

Published on July 24, 2011 16:02

July 17, 2011

Katharine Weber talks about family, lies and The Memory Of All That

I first met Katharine Weber after asking her for a blurb for a novel of mine, which to my delight, came with an offer of friendship. We quickly became confidants, and now spend hours talking about books, writing, food, art, music and gossip, too, of course. Her career is enviable. She debuted with a story in the New Yorker, and three of her novels were New York Times Notable books. Her extraordinary just-out memoir, which is also her sixth book, The Memory of All That: George Gershwin, Kay Swift, and My Family's Legacy of Infidelities, has already garnered an A from Entertainment Weekly and raves from Booklist, Publishers Weekly and More. I'm so happy to have Katharine here! (Thank you, Katharine!)

This book defies labeling--though it's the story of your family, it's also the story of so many other things, so you can't really call it a traditional memoir. Can you talk about how you stretched and changed the boundaries of the genre?

The book really isn't a traditional memoir, is it? It is not my story in any complete or historical sense. It is my sensibility and my awareness of this vast cast of characters in my family, starting with my mother and father, but it is certainly not the story of my life in a traditional sense. At the same time, even though there is a great deal you won't learn about me from this book, in some essential ways, it really is very intimate and personal. These are my people, and these are my experiences of my people, and here is more of their story which I have researched in the writing of the book. So in a certain sense, it is a researched group biography hybridized with a very personal memoir strategy. Is that stretching and changing the boundaries of the genre? I had no idea I was writing the book this way when I set out to do it. Though I did want to use my father's enormous FBI file as an organizing element with the contrast between my memories of childhood in contrast to the FBI 's way of telling the same story about my family. I thought the book would be much more about the ways we tell our stories.

How would you say writing this book changed you? Did anything surprise you? Did you have something in mind and then the book took on a life of its own?

I do think writing this book changed me, and in some unexpected ways. For one thing, it really expanded my capabilities as a writer in some practical ways. I knew how to write a novel, or at lest, after five novels I knew how to teach myself how to write each of those novels and will know how to teach myself to write the next novel, and the next. But I didn't know how to write a book like this, a book based entirely on actual people and actual events, an amalgamation of what I experienced and remembered about them, what I knew about them, and what I discovered as I researched these many very different family members and their stories. I kept getting deep into the material and losing my perspective, feeling that every tiny fact and discovery had equal value and weight for the story, which wasn't the case.

If I had been writing fiction, I would have been able to recognize the extraneous material as I wrote it or at least as I revised it, so I would have had better control of the shape and pace of my narrative as I wrote. Instead, I labored over pages of material, revising and revising, only to recognize (often thanks to my editor John Glusman, who read and line-edited the manuscript thoroughly for each of three drafts) that I had overdeveloped something that didn't really serve the story at all and it needed to be eliminated.

John also confronted me with the chaotic and associatively unruly order of the first draft. Once again, my experience as the author of five novels had not prepared me to write in a less organic and more pre-determined and straightforward structure. I can trust my novelist's instinct when it comes to layering a narrative with associative and tangential interludes, while always keeping the narrative arc in mind and moving the character development and story forward, often in very nonstandard ways. But that same narrative instinct had led me to craft something far too organic the first time through -- which is to say I had lost control of the narrative because I was inside it and hadn't succeeded in maintaining a long view at all.

And at first I didn't have a "voice" for the story, because I wasn't inhabiting a narrating character, whose needs and wants would be clear to me, I was telling my own story. I always interrogate my narrator as I write, asking her, What do you want? What do you do to get what you want? Can you change in the course of this story? Do you change or do you fail to change? In what ways does this matter to this story? But I had failed to question myself. I needed to develop my own narrative voice, which I think I did, in the end write the book the way I would write a novel. So on the one hand I was to dependent on my experience as a novelist, and on the other hand I wasn't at first aware of the necessity to work at developing the narrative voice in exactly the same way I would for a novel. All of this was a giant learning curve.

Perhaps the change and surprise for me that came out of The Memory Of All That was realizing at the very end that I now had a profound understanding, for the first time, of the difference between grievance and grief. I think I moved from grievance to grief from the start to the finish of the book. So that is the answer to the question I pose to the main character of every novel, among the questions I had to pose to myself, about change, and how it signifies for the book.

I'm very interested in process. Can you talk about what you're working on now and how you work at it?

I am writing a new novel. I have been spending a lot of time with it in my head, though I have very little to show for it yet on the page. It has taken me a long time to accept that this is my process, this stage of development which might look like "not writing" to someone else. There is value for me in holding the increasingly complex vision of the novel until it has, to quote Virginia Woolf "grown heavy in my mind." When I discovered something Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary, when she was beginning to write The Waves, it was a huge relief to me -- I had a revelation about this process of developing a new novel with which I had previously struggled. Something I had always thought was a liability, this delaying of the moment when I would begin writing it all down, I now understood was actually an asset, and it gave me permission to write the way I write. This is what she said: "I am going to hold myself from writing till I have it impending in me: grown heavy in my mind like a ripe pear."

What kind of legacy do you think our families leave us and how can that be understood in writing?

What an intriguing question, Caroline. I think it varies tremendously from family to family, don't you? Starting with how families define for themselves what a legacy is. In some families, the legacy is absence, secrets, mysteries, lost connections, disappearances, missed opportunities. In other families it's Aunt Polly's good silver, the earlobes that mark you as a Worthington, the family tone deafness, and the right to be buried in a family plot where all your ancestors have been laid to rest since the Pilgrims landed. How we write about legacy seems to me the basis for many of the great novels and plays. Our heritage, our legacy -- does it define us, or do we define ourselves in conflict with it?

I think one of the most intriguing written documents of legacy that human beings create is very literally about legacy -- a Last Will and Testament. In my case, as I write in The Memory Of All That, I discovered that my father had cut me out of his Will in response to the news that I was pregnant with my first child. In my novel True Confections, disputes about the intentions underlying ambiguous language in a Will are central to the plot. What someone leaves behind in his or her Will, in addition to material objects and money that can delight or harm the recipients, can be anything from fantastic generosity to cruel rejection.

Can you talk about your writing process? Are you an outliner?

I have learned to be an outliner because, challenging as it is to do it, working from a solid outline can save you from wasted energy going up a lot of blind alleys and it can make you a more efficient writer. On the other hand, my method is pretty much to make an outline and then deviate from it significantly at certain junctures. If I stuck to the outline all the way through a first draft, to the end, with no deviations, that would herald a failure of some kind on my part. It would be a sign that something about this draft wasn't really succeeding.

Your novels have been optioned many times for films--how difficult is it to let go of a project and see it transformed, sometimes into something very different?

I would love to have more experience with this sort of difficulty, I assure you! I have seen a lot of scripts, but nothing has made it to the screen yet. However, a short story of mine, "Sleeping," has been made into an award-winning short film by Doug Conant and Group-Six Productions, and that was an intriguing experience. I loved the look and feel of the film, and the casting was terrific. The ending was changed -- in my story there is ambiguity, while in the film there are concrete explanations. I wouldn't have scripted it the same way. However, it's not my film, it's Doug Conant's film.

Published on July 17, 2011 16:34

July 16, 2011

Rachel Machacek talks about dating and The Science of Single

I first met

Rachel Machacek

at a writers' dinner at the Gaithersburg Book Festival. I was hot, tired, low-energy and the truth was, I really wanted to just go to sleep, but I loved the writers I knew who were coming to the dinner and I wasn't about to pass it up. The fabulous Eleanor Brown (The Wicked Sisters) brought Rachel and as soon as she told me that Rachel was writing a book about the dating scene, I was interested. Rachel was so funny, so entrancing, and her stories so wonderful, I knew I had to read her book and have her on here. Thanks, thanks, thanks, Rachel!

I first met

Rachel Machacek

at a writers' dinner at the Gaithersburg Book Festival. I was hot, tired, low-energy and the truth was, I really wanted to just go to sleep, but I loved the writers I knew who were coming to the dinner and I wasn't about to pass it up. The fabulous Eleanor Brown (The Wicked Sisters) brought Rachel and as soon as she told me that Rachel was writing a book about the dating scene, I was interested. Rachel was so funny, so entrancing, and her stories so wonderful, I knew I had to read her book and have her on here. Thanks, thanks, thanks, Rachel!So what IS the science of single?

I think there are two parts to being single. Like, literally, learning to be single and enjoying your own company. The other part is learning to date, the inference being that one is looking for some sort of a relationship. I believe most of us are. Ultimately, it's less of a science, more the art of delicate negotiation between embracing your singledom and being open to the possibility of something more. Seems like a no brainer, but sometimes it's like opposing forces pulling you in two different directions, arm tendons straining.

What was really fascinating was how your relationship with Jeb actually suffered because of the book you were writing. Care to tell that story?

Oh Jeb. That relationship was going to suffer no matter what. When you get involved with someone and dig into their life, there's always something. Some sort of issue, boundary, stuffed-to-the-gills luggage that you uncover, cross, unpack. And whatever it is that you find out about the other person, well, it's either a dealbreaker or it's not.

When Jeb found out I was writing a book about my dating experience, we weren't even two weeks into dating each other and I hadn't had a chance (found the nerve) to tell him yet. I still don't know how he found out. But me writing about dating – writing about me and him – coupled with a number of difficult things going on in his life – it all became one big ole dealbreaker. I sort of understood. I sort of didn't. He was a private person, so I think that probably had a lot to do with it.

Of all the dating sites you tried out, which was the best and which was the worse, and why?

They all worked. I found dates under every single cyber rock I overturned. I prefer the ones that are easy on the pockets or, even better, free. OK Cupid is my current go-to. It's free, it's well designed and it's one of the most popular sites in DC right now, so lots of people looking for dates there. I disliked eHarmony the most because there was so much ePaperwork. Pages and pages of questions and forms. Took me 30 minutes to get through it all. The dates were fine, but not worth the fuss. And it's pricey.

What was the writing of this book like? Did you have a preconceived idea of how the book might end? What did you learn that surprised you?

I had absolutely no idea what I was getting into with this book. If I had, I still don't know if I would have been able to finish it. (I would have. But you know what I mean.) All that dating. All those men. All the break ups. The self discovery. It was traumatic and dramatic and sometimes really wonderful. I had a magnifying glass on my thought process and feelings for a full year while I experimented with dating, and then after all the dating was said and done, I sat down to write it all out, reliving the entire year in roughly five weeks. There were a lot of tears. A lot of worry about hurting the feelings of the people I went out with. (I used aliases, but they know who they are.) Laughing too.

The thing that surprised me: I thought my problem was not being able to meet men. Turns out, that was the least of my problems. As one salty reviewer indicated, the problem was me. I had a terrible of cycle of being way too picky and then not picky enough. Filter on. Filter off. And I was looking for this chemistry. Like the entire fireworks display in DC crashing over my head at once. It's just not practical. There should be some chemistry, but you gotta let a relationship grow.

What's obsessing you now?

Baking. Moving beyond the casual date. Portulaca and my garden in general. Sitting with uncertainty. Zucchini bread. La Roux. Moon phases. Off-the-cuff haiku. Knee-Jerk mag. My Second Book.

Of course I have to ask, how are you dating now?

I'm dating someone who I feel like I should have met years and years ago. (It's pretty new, him and I.) But we've been in each other's stratosphere for a long time. While I was too chicken to actually walk up to him when I was three feet away from him on the metro a few months ago, I finally friended him on Facebook. Thank you Mark Zuckerburg for allowing me to be simultaneously introverted and outgoing in the click of a button. My old dating coach would have failed me. But hey, he emailed.

Published on July 16, 2011 10:36

July 6, 2011

Dawn Tripp talks about Game of Secrets and how writing is like being in love

I can't remember when and how I met

Game of Secrets is genius, and I'm not just saying that because we're friends. Intricately structured and exquisitely written, it pulls you in like an undertow and it truly is startlingly original. Thanks so much for being here, Dawn.

I can't remember when and how I met

Game of Secrets is genius, and I'm not just saying that because we're friends. Intricately structured and exquisitely written, it pulls you in like an undertow and it truly is startlingly original. Thanks so much for being here, Dawn.

I'm always interested in process. Game of Secrets has such an intricate structure, where information is slowly revealed. Did you plan all this out, or did it happen more organically?

This novel felt different from my first two—a literary thriller with a small-town murder at the heart of it—a mystery played out through a Scrabble game. But it didn't start that way.Late spring, several years ago, I was working on something else—a historical novel—and out of the blue, over the course of a month I wrote a series of forty poems. I haven't written poetry since my twenties, although as a writing form, it is my primary impulse. And what I noticed is that those forty poems were all digging into things I couldn't quite bear to write straight out in narrative, and so they surfaced, in bits and pieces, in those poems. I wrote about a mother and her son, a friend who died abruptly, a girl crossing over a bridge, a car accident, an illicit love and its consequence, a dream stubbed out, I wrote about an unconscionable act of cruelty, and a young man staring at a woman across a moving street while the rest of the world fell away. I wrote about the loss of a child.It didn't take much for me to see that those poems had a life, an emotional complexity that the novel I was working on did not. So I ditched that other book, almost 400 pages of it, because these were the stories I wanted to walk into, these were the lives I was on fire to tell.Out of those fragments, there were three that I couldn't stop thinking about: the image of a 14 year old boy driving fast down an unfinished highway in a borrowed car; the image of two women playing Scrabble; the image of two lovers, a man and a woman, meeting in an old cranberry barn. I did not know their names, but I could feel the charge of a threat and the desire between them—I knew that this would be the last time they would meet. I had already filled a notebook when an older man from town told me a story of a skull that surfaced back in the 60s out of a truckload of gravel fill, a neat bullet hole in the temple. The moment the story was out of his mouth, I knew that skull had everything to do with the two friends playing Scrabble, the lovers in the cranberry barn, and with that boy driving fast down an unfinished highway in a stolen car.My best work starts in this place: with fragments that are burning, sharp, acute. They might feel linked, and I might glimpse the larger story they belong to but, curiously, the longer I can resist the impulse to pin everything down into place, the longer I can keep things open, the more necessary the writing becomes. That doesn't mean the order isn't there. It doesn't mean some dark underside of my mind hasn't already figured it out. I put my faith in the fact that there is such a cogent order. And I write to discover it.All three of my books are highly structured, but not in a traditional linear form. In the novels I admire most, structure—no matter what form it takes—serves the voice of the narrative. As a result, there is a certain dreamlike immediacy, a certain life of the work that takes precedence, a nuanced undercurrent of thought and feeling that runs through the story and is absorbed by the reader in a more visceral, intuitive way.

I loved the haunting metaphor of the board game. Can you talk about why you chose it, and how it came about?

I love Scrabble. I grew up playing with my grandmother. She and my father always played games—they taught me pitch and gin. When my aunt was visiting, they needed a fourth, and so they taught me bridge. But the game I loved was Scrabble. I remember the thrill I felt when I was old enough to keep my own letters, to have my own rack. We would all play after lunch, then after a game or two, my aunt and father would drift off to something else. "You want to play again, Nana?" I'd ask. And my grandmother would nod, light another cigarette, and start flipping over the tiles. We'd play game after game, uThe book has a kind of syncopation to the writing, an inescapable rhythm. Paragraphs stop short and then are connected again. There are character asides and all these different voices come together in a real and poetical way. Was this a deliberate choice or did it evolve?

I grew up writing poetry. Still now, when I take time away from a book I am working on, to let my mind go fallow and do its underground work—I read poetry. Most of the novelists I adore have a certain cadence to their work. I have faith in what you call that 'inescapable rhythm' of a narrative. I feel that along with 'voice,' it's a key element of creating fiction that is often overlooked. Rhythm draws a reader through a story. The meanings of words touch the mind—the twists in plot engage the intellect—but that rhythm calls forth a deeper, more intuitive connection to the lives of the characters, their struggles and their fates. A shift in rhythm allows a reader to feel a shift in thought, a change of heart, that breath-caught-sharp moment of a revelation. I strive to keep my language spare, but I always have that attention to the rhythm pace of a sentence, a paragraph, a passage—and its emotional effect. One consequence of this is that when my editor takes a pen to my draft for a line-edit, I don't mind at all if she draws a big X through a paragraph, or even suggests I cut a page. I'll make that cut easily. But if she cuts a word or two in a sentence and the rhythm is thrown off, I have to go back and rework that line until the flow and cadence feels right.In this novel, I wanted to write a complex, but fast-paced story. This was something that felt critical to me, not simply because Game of Secrets is a literary thriller, but because pace is something I want to master. I took an extra year to go back through and rework this book. To cut out the chaff—to pare out even moments I may have loved but that felt extraneous to the story and its arc. It's essential, I believe, to learn that kind of ruthlessness—where you can let go of what you long to keep—it gives what remains a kind of luminous intensity. Things rise up, breathe, in a different way. I have a file for those cast-offs. I go back through them sometimes and strip-mine what still has life for me—shift the details, and transform it, into my new work.

What is your writing life like?

When I am in a story, it's like a shadow that is always with me. And that is true whether I am at my desk, out for a run with the dog, driving, sitting on the dock, or folding the laundry. That story is always falling through me—words, half-thoughts, some knot of a scene I have been wrestling with that finally begins to unravel. In the early stages of a book, I turn my back completely on that adage 'write what you know.' I write what moves me, what I am impelled by. I rarely start at the beginning. More often somewhere in the middle—it's like an ocean—this early stage, all tumult and wind-shift. Everything is distance. Everything is possible. I love that. I write my early work longhand. Every draft starts with a pen against a page. For me, there is a certain kinesthetic joy in the act of writing, which engages the intellect, but ultimately serves a more primitive, intuitive mind, what Mary Oliver has called 'the dreams of the body.' Sometimes I write on little slips of paper—receipts, grocery lists, throw-away things that I then transcribe into notebooks—and from there to my laptop. I am oddly superstitious about the pens I use, the notebooks I use. I am particular about who I show my work to, and when. Not out of fear of judgment, but because when I am really living in a story, I am open. I don't my polish my drafts up too soon. I leave notes in the margins, I leave some passages entirely without punctuation. I leave things raw, untidy, open to change. That openness, I feel, is critical. I find that when I can let myself stay open to possibilities in a story that I may not yet have uncovered, when I can let myself be driven by what I do not yet know, the story often turns, deepens, in unexpected, revelatory ways. Every six months or so, I need to leave my work for a week or two—oddly enough, this is never easy for me—but it clarifies my seeing, it clarifies my vision of the story. My mind sorts things through while I am looking away. During that time, I walk the beach and the woods with the dog. And I read. Sometimes contemporary novelists. Sometimes I re-read short novels that I love, that kick open windows in my brain and somehow never fail to change me, in some slight but vital way, with each re-reading. Most often though, it's poetry I am drawn to. W.S. Merwin. Rilke. Eliot. Seamus Heaney. Mary Oliver. I don't know what it is about poetry that does its work on me. But it's like entering another element. It's like breathing different air. Poetry is not what I write. But it's deeply intrinsic to why.

You and I have had –and continue to have—long conversations about writing, one of which I put up on this blog. Yet many writing books out there don't dig into the angst and the obsession, but instead focus on the how-to of craft. Why do you think this is, and don't you feel it's more productive to get at the heart of what happens to a writer when he or she struggles to write? (I realize this is a loaded question, but I can't resist asking it.)I think it's easier, safer, to focus on the how-to of craft. Writing is a discipline. Writing takes drive. No doubt about that. You need to stick with it, passage after passage. You need to work and rework a sentence, a chapter, a draft, until it breathes. And yet, there is that other ineffable, essential and immutable aspect of the process—what is mystical, obsession, inspiration, doubt—all of that, which to my mind are only different turns of the same coin. And so much more challenging to pin down or render into words.I often feel that in my fiction, I work toward what I cannot say. I write for what lies just past words. Every novel I have written has started with some dark secret I can't quite bring myself to tell, and so I tell it on the slant, through the story.For me, those early months are breathtaking, feverish—it's like being in love; it's like having the flu—and even though I can't always see how the disparate pieces will fall into place, I have come to have faith in that particular state, which is often beyond the reach of intellect, and coming from an altogether different mind. There is doubt, sometimes piercing doubt (will this all work out? can I pull it off?), yet that uncertainty—when you write into it—can be as galvanizing and as necessary as the dizzying rush of inspiration that is so much easier to adore.Game of Secrets was an unusual book for me in the sense that I felt like I was continually being overturned. I knew in my gut that I had to stay open to that. I had to keep my balance with that. Again and again, I would discover some new element that was not in my original vision for the novel, and often in consequence, the arc of the story would change, and I would have to let it change.I wrote what I thought was the ending of the story early on. I fell in love with it. It became that kind of horizon a strong ending can be that drives you, day in, day out, to create the 300 pages leading up to that moment. What I did not expect, and could not have foreseen, was that in fact that ending was not the climax. The most powerful revelation was something I was writing toward without even realizing it, until all at once, I did. A story can do that. A game can do that. It can all turn at the end.

Published on July 06, 2011 06:11

July 3, 2011

Gwendolen Gross talks about sisters, writing, obsessions and The Orphan Sister

I've known

Wendy

for quite a few years now. I don't remember how we met, exactly. I think we both had novels out at the same time, but we became instant friends. The Orphan Sister really struck home with me because it's about belonging and family ties and all the murky things I'm obsessed with. Yep, I blurbed it, and I called it "breathtakingly original." And I meant it. Thank you so much Wendy, for being here on my blog today and answering my pesty questions.

I've known

Wendy

for quite a few years now. I don't remember how we met, exactly. I think we both had novels out at the same time, but we became instant friends. The Orphan Sister really struck home with me because it's about belonging and family ties and all the murky things I'm obsessed with. Yep, I blurbed it, and I called it "breathtakingly original." And I meant it. Thank you so much Wendy, for being here on my blog today and answering my pesty questions. What is it about sisters that is so compelling?

What is it about sisters that is so compelling?

Sisters! Well, first of all, I have three, one of whom has a different mother and who is 20 years younger than I. She was the first baby for whom I fell, completely; people asked if she was my first (thinking she was my baby), and I said, "No, I have two other sisters!"

Anyone who has sisters knows you share many things: frame of reference, in-jokes, adolescent contempt for parents, deep and sometimes jealous love of those same parents. Sisters give you a model, a mold, for many of life's relationships. Shared experience and competition, both. I think of my sisters daily, but viscerally, rather than intellectually. My son smells like my older sister, Claudia, when he wakes up (a wonderful smell, not morning breath). If I make an absurd nonsequiteur no one gets, I think: Becca would understand, or: I have to tell my friend Cindy (with whom I don't share parents or childhood, but somewhere, historically, we must share genes). Since so much of sisterhood is collective circumstance, adoptive sisters might have their own shared frame--but different matting or something. That could be another book!

What I loved about this novel was how different it seemed from your previous ones (not that I didn't love them, as well.) Did you feel that you were treading new ground and how terrifying was that to contemplate?

First, thank you so very much! As you know, someone who has read your book is someone you have loved, even if only a little, even if you'll never meet (though I've been lucky enough to meet you). I think writers tend to have both infinite stories and finite truths--the truths emerge in the exploration of character, place, plot. With this book I hoped to make something as active and immediate and suspenseful as I might, while telling the slower truths of familial and romantic love that emerged from the story. I had the kernels: polyzygotic triplets, father with a secret life, one sister who feels separate, and I tried to balance the elements of a novel: dialogue, internal monologue, exposition, etc. I wanted to write a good read! I wanted to write a friend! A sister!

The book really probles the whole issue of who we are--and who we want to be. Do you ever think the two can be one and the same?

Yes.Of course, it may take all the living and it may be that the getting there is the best--and only lasting--part. Nothing stops until we die (does it stop then?); we keep building our own stories of conversations, petted foreheads, mistakes, bike rides, tweets, births, meals, love.(Caroline--you're inspiring philosophy!)

What's your writing life like?

My writing life is spackled between the bricks of parenthood, teaching, home, exercise, friendship, sleep. I write while my daughter's at gymnastics, while my son learns photoshop. I sneak away while they're in school and write at a cafe or bookstore with my laptop. I find scrappy notes of great importance (on the back of receipts) stuffed in the pocket of my riding breeches. The truth is, I don't know if I will be any more productive when my family needs me less immediately. I suppose I always need space and time to thing, but also chaos to control by making fiction.

What's obsessing you now?

Writing-wise: another family secret that isn't my own--and the fallout of secrets and lies.Also: the way a piano owns fingers.Also: horses.Also, in reading: how authors make their narrators fallible but strong. I'm reading piles of YA and MG fiction because my kids want me to read what they love, and I'm staggered by some of the writing (The Underneath!) and trying to figure out whether storytelling for different ages really is any different.

What question didn't I ask that I should have? (I just read the answer and I'm blushing furiously.)

What have you recently learned from following the success story of the eloquent, dazzling, benevolent Caroline Leavitt? You have to put all those adjectives in!

Answer: Always, always, always be kind of fellow writers, who are also your best and most important readers. We mustn't ever think of writing as a competition; there's room for every story, and we do this not because it makes us famous or rich (though I wish that upon my favorites, at least the rich part), but because books, stories, have saved and enriched our lives. You are not only an extraordinary writer, Caroline, but a teacher and woman of patience, kindness, and generosity. Let us all aspire to the same!

Published on July 03, 2011 09:23

June 28, 2011

Michael Kimball talks about Us

One of my favorite books of the year is Us by Michael Kimball. I carried it around with me on the subway, and when I finished, I couldn't let it go. I kept it by my desk and kept rereading parts of it. Michael's also the author of four other fantastic novels including Dear Everybody and he's responsible for the innovative Michael Kimball Writes Your Life Story (On a Postcard), which I have inexplicably been too chicken and shy to do. He's one of my heroes, and I'm just dazzled to have him here.

What sparked this particular book?

Us started out as a kind of an accident. I had approached the novel a few different ways, a few different times, none of which worked. Then I was sitting at my desk one night writing longhand and I wasn't really thinking about anything in particular, but I just started writing this voice—the one that opens the first chapter—and it seemed to capture a feeling that I had in mind. I wrote a few chapters before I realized that I was writing about one pair of my grandparents who were around a lot when I was growing up, that I was writing about their last days together. I used my feelings about them and other people in my life that I have lost to write the novel, a kind of method writing, so to speak. The novel was written out of those feelings of loss and grief, but also very much out of love. I wanted the reader to feel what I felt or at least to understand it and to honor it. And there was a desire to fill in a void. I was trying to make something to replace two people who could not be replaced. I was imagining more life for my grandparents and it was a small comfort.

I deeply admire the structure, which is a moment-to-moment account of a particular time in an old marriage. What made you decide on this structure? Also, what strikes me is that this particular time is very much indicative of the whole and long marriage.

I found the structure after I found the voice. There was a really specific syntax, a particular way of describing things, and an especially particular thought-structure—the little leaps between his wife and almost everything else that he encounters. After that, I imposed some unspoken rules on the narrator—what he could describe and how. Limiting the scope of his narrative enacted a kind of close attention in what he tells us. There is great care and great love in that close attention, which makes it a culmination of sorts for their long and loving marriage.

The writing in this book seems so clear and clean and almost simple, yet every word is like an iceberg, with levels of meaning that radiate outwards. I've told you that I'm asking all my UCLA students to read this, as an example of what writing can and should do. How conscious were you of paring things down as you were writing, or does this simply come naturally to you?

I'm very conscious of paring things down. I'm trying to tell as much story and convey as much feeling as possible with as few words as possible. I'm making some assumptions about what a reader brings to reading a book when I do this. There is a lot that fiction writers don't need to describe anymore. I get to that pared down state by drafting material and then distilling it, getting rid of everything that doesn't seem absolutely necessary. This takes a different form in Us (where feeling is the thing that is compressed) than Dear Everybody (where it is story that is compressed). Also, I'm trying to write the kind of thing that I would most like to read. I want a kind of intensity, also a certain narrative speed, two things that compression can make happen.

You've said that the book is about "how love can accumulate between two people." It's such a deeply moving novel, and yet, despite the sorrow in it, it's also incredibly optimistic about love. Can you comment on this?

The behavior of the main narrator is driven by grief, both anticipatory grief and then actual grief, which becomes more extreme as the novel progress. The extreme grief is a sad and terrible thing, but only because the long love of their marriage is such a great and beautiful thing.

Can you talk about your writing process?

I used to have a terrible time getting anything down on the page. Once I did, once I had something to work with, then I would revise endlessly. But my writing process has evolved quite a bit over the years, I have found ways to open myself up on the page. I try to be brave on the page. I move into any space where I sense any kind of resistance—personal, emotion, aesthetic, etc. I try to be fearless. I try to let the voice tell the story and let the story tell me what it is. I try to find new ways to get from sentences to sentence. For instance, sometimes I find a word or phrase or turn by looking at the surrounding acoustics or graphics rather than by considering the semantic logic. It can lead to some surprising choices that I couldn't possibly think of, but that I only have to recognize. It moves the narrative in different ways and helps the energy and the tension build. More and more, I'm trying to be open and receptive to anything happening on the page.

What's obsessing you now?

I just finished writing a new novel and I haven't been able to stop thinking about it. It takes me months to let go of the voices from my novels. So I'm at once obsessed with what I've just done and with trying to figure out what the next thing might be. Also, I've been trying to figure out how to make a short film using this abandoned swimming pool that's been filled in with dirt and has grass growing where the surface of the water would be. I can see some of the action and hear the soundtrack, but I feel as if I'm missing an important element, and I have no idea what it is.]

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

It would have been nearly impossible to come up with this, but you could have asked me what position I play for the Poet's Athletic Club, which is a co-ed softball team made up of Baltimore writers and artists. I would have told you that I haven't played organized anything in a couple of decades and that playing first base for the Poet's Athletic Club is so much fun that it makes me feel like a giant kid.

Published on June 28, 2011 11:46

Ellen Sussman talks about letting your writing marinate

Ellen Sussman 's French Lessons, about how a single day in Paris changes the lives of three women, is already racking up some raves, including Ann Packer, who says, "This is a novel to savor." I asked Ellen if she'd write something for my blog, and I'm honored that she did. Thank you, Ellen!

Let it MarinateEllen Sussman

I tried to write a novel about a young woman's relationship with her dying mother about six months after my mother died. The novel failed. I didn't put my creative energy into the work – I was reporting from the front lines. That's not the way good fiction gets written – at least for me.

I need distance. I need separation. I need to forget what really happened and let my imagination soar.

I lived in Paris from 1988 until 1993. I loved my time there, even though I was raising babies and struggling with loneliness in my marriage. I was writing while I lived in Paris – but never about Paris. I'll wait until I get home for that, I told myself.

Years passed and I never found my Paris story. I knew I had to write about Paris – no experience in my life had been richer, lived in such big bold colors. And it was a complicated time – I experienced life as a foreigner, with a new language and culture. I stepped outside of my comfort zone. I learned more about myself in that year than at any other point in my life. So why couldn't I write about it?

I wasn't ready. I needed to let those memories build flavor and intensity. I wanted to forget in order to remember those stories in a brand new way.

A few years ago, I was invited to teach at the Paris Writers Conference. My husband joined me for the trip and I bought him a gift – a week with a French tutor, walking the streets of Paris while I taught. After the first day, I figured out that not only was the tutor good at her job, but she was also young and beautiful. What a gift! And soon I had an idea for a novel: a happily married man feels the first stirring of lust for another woman – what does it do to him and to his marriage?

But I have so much more to say about Paris, I thought. And so I created two more Americans and two more French tutors, all of them walking the streets of Paris, talking about love and loss. The novel, FRENCH LESSONS, wrote itself in a mad rush. I had all that material, all those memories and impressions, ready to pour into my story.

Give me a good ten years to let an experience marinate. Over those years, I forget the details and the memories become fuzzy, vague. So when it's time to sit down and write, I have to create the story on the page. I have to invent character and plot twists – I can't rely on who was there and what happened, because I just don't remember! That's when my fiction comes alive – that's when I'm making it happen on the page.

Published on June 28, 2011 11:46

Bestselling author John Shors talks about Cross Currents, writing and more

When bestselling author John Shors sent me a copy of his terrific new novel Cross Currents, he sent a little shell in a box along with it--which I now have on my desk and treasure as much as his book. Both Amy Tan and Robert Olen Butler have called him a masterful storyteller, and I'm chiming in. Cross Currents is an unusual story of a family's drama set against Thailand's 2004 tsunami and I'm thrilled to have John here to talk about it. Thanks, John!

I had asked John a bunch of questions, but it struck me how his answers read even better without the intrusion of my queries, so here they are, and thank you, thank you, John.

I have been fortunate enough to do quite a bit of traveling overseas. One of the most magical places I've been to is a small island in Thailand known as Kho Phi Phi. There are no motorized vehicles. The beaches are perfect. The locals are friendly. When I first traveled to Kho Phi Phi in 1992 I felt as if I had uncovered an unknown slice of paradise. I returned every few years thereafter, and felt even more connected to the setting.

On December 26, 2004, I watched in horror on my television as images of the Indian Ocean Tsunami came to vivid life. Thailand was hit hard, and I soon learned that Kho Phi Phi was devastated. I wanted to fly to Thailand and help, but my wife and I had two toddlers at home, and international travel wasn't practical. And I so I waited, finally returning to the island in 2007. I had expected to see widespread devastation, but the Thais had rebuilt almost everything. During my trip I spoke with many locals who had survived the experience, and their stories of saving others and being saved by others were extremely inspiring. It suddenly occurred to me that no one had ever written a novel about the Indian Ocean Tsunami, despite the fact that it was a global event. The seeds of Cross Currents were planted on that trip. I felt like I had an opportunity to create a special story and immediately starting thinking about how it might unfold.

The research for Cross Currents was fairly straightforward. I had been to Ko Phi Phi many times, so I felt as if I had a good understanding for the island and its inhabitants. The challenge in terms of the research was recreating the tsunami in an accurate way. To ensure success with this, I interviewed many Thais who had survived the event. Their descriptions gave me a strong sense of what happened. I came to imagine how the island was consumed by the wave.

One of my goals with my writing is to bring beautiful places and cultures to life on the page. To make that happen, I visit the places I write about, and get to know them well. Once I have created a rapport with a setting and a people, I then go back to the States and sit down and really think about the story that I want to tell. I create a detailed outline, though I find that once I'm neck-deep in the first draft that the story seems to gain a life of its own, taking me in directions that I hadn't expected.

Well, I'm quite pleased with Cross Currents and am eager to see how people react to it. I'm donating some of the funds generated through the book to the International Red Cross, and am grateful that the support of so many readers allows me to do such things.

As far as what I'm working on now, I'm almost finished with my first draft of a work of historical fiction that is set in ancient Cambodia and has to do with the temple of Angkor Wat. It will be an epic story, somewhat akin to my first novel, Beneath a Marble Sky, which brought the Taj Mahal to life. I haven't written historical fiction for a few years, and it's good to be back in the genre, though all of the research definitely adds a layer of work to the writing process.

And, of course, I'm thinking about future books. I know that I will write ten or maybe twelve novels in my career, so it's important for me to take my time as I ponder what are the best stories for me to write, and for my readers to enjoy.

I also continue to talk with book clubs around the world (via speakerphone and Skype). To date, I've chatted with about 3,000 book clubs, which has been a great experience for everyone involved. It's important for me to try and connect with my readers, and my book club program is one way of doing that.

Published on June 28, 2011 11:45

June 25, 2011

Christine Sneed Talks about Portraits of a Few of the People I've Made Cry

Christine Sneed is incredible. Not only does she have this great, inventive website, that comes with literary brainteasers, puns, jokes, and more, she's also the author of a brilliant collection of stories: Portraits of a Few of the People I've Made Cry (long listed for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award and nominated for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize). I'm thrilled Christine offered to write something for my blog. She's hilariously funny and truly, her collection is genius.

Christine Sneed is incredible. Not only does she have this great, inventive website, that comes with literary brainteasers, puns, jokes, and more, she's also the author of a brilliant collection of stories: Portraits of a Few of the People I've Made Cry (long listed for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award and nominated for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize). I'm thrilled Christine offered to write something for my blog. She's hilariously funny and truly, her collection is genius. A Casual Introduction:

Several of the ten stories in Portraits examine the perils of love and what it means to live during an era when people will offer themselves, almost unthinkingly, to strangers. Risks and repercussions are never fully weighed. Mysterious, dangerous benefactors, dead and living artists, movie stars and college professors, plagiarists, and distinguished foreign novelists are among the many different characters. No one is blameless, but villains are difficult to single out--everyone seemingly bears responsibility for his or her desires and for the outcome of difficult choices so often made hopefully and naively.

Getting Personal:

Q. I've been asked by a couple of readers why some of my characters seem to have easygoing attitudes about infidelity. One reader recently said, "The people I know who have been cheated on don't take it as well as your characters do. Don't you think they should be more upset when it happens to them?" A. My characters actually are upset about being cheated on, but I try not to write scenes that veer toward melodrama. One of my goals with these stories is only to point toward the rage, jealousy and despair – all of the feelings that attend romantic disappointment – and to let readers imagine the rest for themselves.

Q. Why are there so many May-December romances in this book? Do you have an old-man fetish? A sugar-daddy obsession? A. I don't think I have an old man fetish, and I've never had a sugar daddy, but I am always curious about why two people decide to become a couple, and the different worldviews and experiences that two people with a big age gap frequently have to navigate have always interested me. One of the stories, "By the Way," was also a kind of assignment that I gave myself. I wanted to write a convincing story with a twist on the usual May-December paradigm, that is, the woman is the older member of the couple – seventeen years older than her boyfriend. She doesn't believe in her boyfriend's (truly earnest) feelings for her and is afraid that once he finds out how old she is, he will want to break up with her.

Q. How many people have you made cry?A. Not too many, but yes, there have been a few. The title story is about the granddaughter of a famous artist, and after his death, she finds a series of portraits in his study that he titled "People I've Made Cry," all women, incidentally, because he was a lady's man, something that kind of gives his rather prudish granddaughter the willies.

Q. Why should I read these stories?A. I tried to be as honest as possible when writing them, especially about how I believe a lot of people, women in particular, feel about themselves when they're falling in love, or feeling vulnerable to someone, or feeling the desire to be someone else. There's quite a bit of longing in these ten stories, and many insecurities on display. I don't know how interesting it would be to read a story about someone who doesn't ever worry or feel afraid or jealous or angry. I think much of what defines human character is how we handle our insecurities.

Published on June 25, 2011 11:13