Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 123

August 9, 2011

Help send the novel Alice Bliss around the world

I now turn over this blog to a kind of unique promotion, from Laura Harrington, author of Alice Bliss. Laura's inviting everyone to be a part of "Where's Alice Bliss?"

What Is Where's Alice Bliss?Where's Alice Bliss? is a campaign to send copies of the novel Alice Bliss to as many countries and U.S. states as possible. Through bookcrossing.com, copies of Alice Bliss will be registered and tracked as they travel around the world, passing from one reader to the next. Your bookcrossing ID (BCID) allows you to follow your book wherever it goes. It's like a passport enabling your book to travel the world without getting lost. Once your book is registered, you will leave it in a public place with a note inside for someone else to find, read, and pass on, like a modern-day message in a bottle. You will be part of an international movement encouraging readers to read, register, and release books for others to enjoy.

How Do I Join?If you are a teenage or adult book blogger, you are invited to request a copy of Alice Bliss through lauraharringtonbooks.com. Click on the "Where's Alice Bliss?" page and fill out the submission form. The copy you receive will have a bookcrossing book plate on the inside with our "Where's Alice Bliss?" logo. Please go to www.bookcrossing.com to register your book and get your book's unique bookcrossing ID (BCID). Put the BCID in the space provided on the bookmark. This number will allow you to track your book's journey.

What Do I Do When I Get My Copy?Upon receiving your copy of Alice Bliss, you should read and review the book before logging on to bookcrossing.com and following the instructions to "release" your book to someone new. Photograph or video your "release" and upload your images to your blog and/ or Tumblr account and send us a link.

Goal:We want to send Alice to four continents and all 50 U.S. states

How Can I Follow Alice?You can find out where Alice is by going to wheresalicebliss.wordpress.com, see pictures and videos of Alice all around the world on wheresalicebliss.tumblr.com, and get Where's Alice Bliss? updates by following WheresAB on Twitter.

Laura Harrington's debut novel, ALICE BLISS, Pamela Dorman Books, VIking/Penguin, available June 6, 2011: "This may be the Our Town of the 21st Century." Anne Roiphe, author of Epilogue, a MemoirALICE BLISS is a "People Pick" with 4 out of 4 stars.ALICE BLISS: "The Best Books of the Summer" Entertainment Weekly.ALICE BLISS has been selected for the Barnes&Noble "Discover Great New Writers" program.Read more at:www.lauraharringtonbooks.comwww.facebook.com/LHarringtonbooks

Published on August 09, 2011 15:35

August 4, 2011

Rachel Simon talks about The Story of Beautiful Girl

Rachel Simon s an award-winning author and nationally known public speaker. She is best known for her critically acclaimed, bestselling memoir Riding The Bus With My Sister, which was adapted for a Hallmark Hall of Fame movie of the same name. She's also a terrific writer and I'm thrilled to have her here!

Rachel Simon s an award-winning author and nationally known public speaker. She is best known for her critically acclaimed, bestselling memoir Riding The Bus With My Sister, which was adapted for a Hallmark Hall of Fame movie of the same name. She's also a terrific writer and I'm thrilled to have her here!What sparked the writing of The Story of Beautiful Girl? What usually sparks the writing of your novels? (I know, the truly horrific question every writer is always asked--horrific because sometimes we truly don't know!)

No single source sparks my ideas. My first book, Little Nightmares, Little Dreams, was a collection of stories that came from sources as varied as single lines that came to mind as I was waking up in the morning, memories both sweet and harsh that returned after many years, and anecdotes told to me by relatives, strangers, and newspapers. My first novel, The Magic Touch, came from temping in an engineering firm and noticing that the women the male engineers tended to flirt with weren't necessarily the prettiest, but the most full of life. Somehow this led to me coming up with the idea of writing about a woman with magical sexual powers that could restore joie de vivre to those who'd come to feel lackluster about their existence. My memoir Riding The Bus With My Sister was derived from the simple fact that my sister, who has an intellectual disability, rides city buses all day, every day; she asked me to join her and I reluctantly agreed.

I think the simple answer is that ideas can, and do, come from everywhere, but never fully baked. They are only the ingredients, and they cannot blend together without the actual process of writing. A perfect example of this is my most recent novel, The Story of Beautiful Girl.

As I mentioned, my sister Beth has an intellectual disability. When she was born in 1960, it wasn't uncommon for doctors to recommend to parents that they place children like my sister in institutions, but my parents never considered that option. I had little idea about the way people who lived there were treated.

Many years later, I wrote Riding The Bus With My Sister, and started getting asked to do public speaking around the country at disability-related conferences. There I met people whose personal or professional experience involved institutions, and who were eager, sometimes tearfully so, to share their stories with me. Over and over, I returned home, reeling. The reality of institutions had obviously been widespread and affected millions of people—yet no one outside of these conferences spoke about such things. In fact, the only institutions most Americans even seemed to be aware of were institutions for people with mental health issues, which is an entirely different system from the institutions where my sister might have been placed. I began wondering if I could write something, fiction or nonfiction, that dealt with the material, but the subject seemed so massive, I put the idea to the side.

The material, however, didn't stop coming my way. One day, as I was wrapping up a talk, I came across a book at a vendor's table, God Knows His Name: The True Story of John Doe No. 24, by Dave Bakke. In 1945, I learned, a deaf, African American teenager was found wandering the streets in Illinois. No one understood his sign language so no one knew who he was. A judge declared him "feebleminded" and he was put away in one of these institutions. There he remained, despite the suspicion of many staff that he had no intellectual disability at all, until he died fifty years later. The tragedy of John Doe No. 24 haunted me.

Yet I still couldn't figure out how I might present such an emotionally fraught topic.

Then in 2007, the creative writing department where I'd taught for over a decade decided to restructure the department and I was let go. Grieving the loss of a job and students I had loved, I set about trying to figure out what to do with my life. I was sure of only one thing: I wanted to keep writing. Though what I wanted to write about, I didn't know. In this vulnerable state, I sat down with a blank pad of paper, waiting to see what would emerge. Instantly, there it was. The novel I'd been vaguely thinking about all this time.

It is 1968. Night. A rain storm. An elderly widow is reading a book. Who is she, I asked myself, and without hesitation, I knew: she was a retired schoolteacher, in a state of grief. Unlike me, her grief was for a child and a bad marriage; like me, she had stayed in touch with her former students. A knock comes to her door. Who is it, I asked myself. Again, I knew. Standing before her is someone who has my sister's disability—and someone who is like John Doe No. 24. She is the love of his life. Although I don't know it for another fifty pages, he calls her Beautiful Girl. They have just escaped from an institution—and Beautiful Girl has just borne a baby girl. I continued writing, and the whole first chapter spilled out. When I reached its ending, I was as shocked as my readers have been. I had no idea she would say to the widow: "Hide her." That's where The Story of Beautiful Girl came from. It was only bits and pieces of ideas, but they got alchemized by the process of writing.

The story of institutional life is horrific. How did you approach the research and what was that like? What surprised you?

When I started meeting people who'd lived in or worked at institutions, I became interested in collecting books and documentaries about the history and reality of those places. I wasn't actually planning to use them for research so I could write a book; I was simply curious about the material, though I was also sad about how little material I could find, and just how abysmal the conditions turned out to be. Indeed, one of the details that kept sticking in my mind was the connection between low funding from the state and the quality of life, leading to, in one book I read, a situation where the forty residents in each cottage had to share the same toothbrush every morning. It was details like this that made me keep thinking I should do something with this material – but something that would also be about justice and hope and freedom and love.

When I began writing The Story of Beautiful Girl, I created a fictional institution that was a composite of several real places that I learned about from these conversations, books, and documentaries. I also set up a visit at a closed institution a few hours from my house, where a compassionate former staff person drove me around and related memories about the people she'd cared for there and what daily life was like.

Many things surprised me about institutions, and not all of them were horrific. One was that there were devoted, loving staff people, like my guide at that closed institution. Another was that friendships developed among the residents that went on for decades and helped sustain both individuals. Of course, there were chilling details, like the stories of families who were told to stop visiting their sons and daughters, or the abuse suffered by residents (which, in my book, I decided to keep off-stage). But there were also real relationships that formed and made a huge difference in everyone's life. This is part of why I created the character of Kate, the dedicated staff person. It's also why the whole book is a love story between two residents, and their lifelong quest to live ordinary lives where they can be together, living not behind stone walls, but free, unhidden, out in the world.

Did you know when you started the novel, how it would end? Are you an outliner, or a writing-by-the-seat-of-your-pen artist?

I don't outline, even with nonfiction. It's always seemed too constraining. I'm a big believer in the writing process, and the way it leads to depth of thought and intricacies of character that would otherwise have remained unknown. This requires a great deal of faith and discipline, and it doesn't always pay off (I've written many books that just didn't end up working out), but when it does, it's a thrill for me as the writer and, from what others tell me, for them as readers.

In the case of The Story of Beautiful Girl, the ending came to me within the first hour of handwriting my first chapter. This is quite amazing to me even now, four years after beginning that draft. It is something that never happened to me before and might not happen again. But as soon as I realized it, I was able to start thinking about how to get to that ending. I didn't know the answer except in the vaguest of ways, but I trusted that the climax of the book would be so powerful and emotionally satisfying that I was happy to work on that draft another next year and a half, not to mention another couple of years on revisions.

What's obsessing you now?

I'm afraid I can't answer this question. I always keep my work totally private, even from my husband. It gives me room to explore, and room to fail.

What question didn't I ask that I should have asked?

The two main characters, Lynnie and Homan, are not only people with disabilities who are in love, they're also characters who are seldom found in fiction. Even rarer is a story in which the reader gets to view the world through the eyes of a character with a disability. Was it difficult for you to put yourself in their place?

As I've mentioned, my sister has an intellectual disability, like Lynnie, so even though their personalities have little in common, it felt fairly natural to me to imagine the way Lynnie would think, feel, and express herself. Writing her point of view came easily in the first draft. I did have to use my imagination to incorporate aspects of Lynnie's life that are unlike my sister's, especially her many years in the institution, her lack of education, and her selective mutism. But I supplemented my imagination with research, conversations, and interviews with other people who've had those experiences, or have been close to someone who has, and then revised endlessly.

The same applies for Homan, including my ease in the first draft. I was, though, even more careful, since I am not, nor am I related to, anyone who is deaf. (I am also not related to anyone who is Deaf, which is the way those in the deaf community who have a strong identity as a deaf person and are involved in deaf culture, write about themselves.) In terms of his ethnicity, I did have a personal connection; my sister's boyfriend, Jesse, is African American, and some of the stories he's shared with me from his childhood informed my understanding of Homan's past.

So do you agree with the writing dictum, Write what you know?

Not really, as that would eliminate the possibility of Flaubert writing about the adulterer Madame Bovary, or Nabokov writing about the pedophile Humbert Humbert, or Flannery O'Connor writing about a girl with a wooden leg.

I think it's just as important, if not more so, to write about what matters to you. For The Story of Beautiful Girl, it just so happened that I did know about some of the things that mattered to me. But I didn't know about a whole lot more. It was my interest in the topic that made me learn what I needed, and then trust, over several years, that the writing process w

Published on August 04, 2011 08:52

Lesley Kagen talks about revisiting characters and Good Graces

Lesley Kagen is an actress, restaurateur and New York Times bestselling author. Her newest novel, Good Graces, will be released on September 1st, and it's a fabulous book. I asked Leslie if she'd write something for my blog, and I'm honored to have her here. Thank you, Leslie!

Right Where I'd Left Them

When my debut novel, Whistling in the Dark, was released, much to my shock and delight, readers feel in love with the two little sisters trying to make a go of it in Milwaukee during the summer of '59. (With all the wonderful books out there it really is a minor miracle when one makes the New York Times bestseller list, which I will have engraved on my tombstone.)

Of course, I was not at all prepared for the aftermath a successful book would lay at my feet. Interviews. Book signings. Fan mail so sweet it made a crusty broad weep. But the most surprising unexpected gift of all was the book clubs invitations. Not having participated in one before, I had no idea how wonderful these woman gatherings would be! They fed me, offered me alcoholic beverages. Sometimes we even managed to talk about the book. Younger women seemed intrigued by the old school setting, the seasoned gals adored the nostalgic time period. Some wanted to know if it was difficult to write in a ten-year-old's voice. (Not really.) Others wondered how much of the book was biographical. (More than you'd think.) But the one comment all the book clubbers had was, "We want to know what happens to the O'Malley sisters. When will there be a sequel?"

"Never," I told them with much certainty. I'd already moved to small town Kentucky where my second book Land of a Hundred Wonders is set and was enjoying the southern comforts so much that I decided to stay put for my next book as well.

And then a funny thing happened. Soon after I handed in the Tomorrow River manuscript to my editor, I found myself aching to do what I'd told the book clubbers I would never do. Revisit Whistling in the Dark. I was missing the characters. The smell of the chocolate chip cookies that permeated the neighborhood. Drive-ins. The lingo. So I packed my literary bags and headed back to Milwaukee.

I thought my biggest challenge in writing Good Graces would be to recapture the voice of ten-year-old narrator, Sally. She'd been through the wringer the previous summer. And Troo, that little vixen…would she have changed? How had life treated the sisters while I'd been gone?

I needn't've worried. Those girls were right where I'd left them. On the corner of Vliet Street, listening to an aquamarine transistor radio, snapping their fingers to the beat. "What's the word, hummingbird?" they grinned and asked.

Oh, man, it was good to be home.

Visit her at LesleyKagen.com and on facebook.com/LesleyKagenBooks.

Published on August 04, 2011 08:45

August 2, 2011

Ken Salikof talks about books as time machines

Ken Salikof is a sharp, funny writer, and a friend. Paris To Die For, written under a pen name, is just as sharp and funny, too. 'm honored to have him on the blog today! Thank you, Ken!

Some books are like time machines. Want to know what it felt like to live in New York in 1882? Read Jack Finney's classic Time and Again (1970), which is, coincidentally, about time travel. Want to experience the horrors and heroics of the Indian Sepoy Mutiny of 1857? Read J.G. Farrell's Booker Prize-winning The Siege of Kirshnapur (1973).

I tried to join the august company of these writers when I found out about a letter written in 1951 by a 22-year-old Jacqueline Lee Bouvier, in which she reveals the possibility of going to work for the CIA. My imagination immediately captivated, I instantly conjured a novel in which Jackie, as a neophyte agent for the CIA, would have an espionage adventure in Paris, her favorite city, in 1951. The task at hand became researching Paris in that year and recreating it for the reader to achieve that all-important time machine effect.

Each day, at my computer, the first thing I would do was play Henry Mancini's propulsive theme from the movie Charade, whose Hitchcockian blend of romance and suspense was my tonal inspiration. Then, having done my research and viewed as many period photographs and artifacts as I could find, I let my mind transport me to post-World War II Paris. I certainly gave my imagination a workout. I have never stood atop the belltowers of Notre Dame Cathedral, and yet I was describing what a fleeing Jackie would see and feel from this vertiginous vantage point. I have never been in a dangerous Vespa chase through the streets of Paris, but here I was dramatizing how Jackie would experience just such a pursuit.

In a way, this was an easy period to write about. Christian Dior had just created his signature "New Look." Marcel Marceau was first making a name for himself as a mime. And I peopled my narrative with cameos by once and future personalities who either were or could have been in Paris at the time. It was such a rewarding experience to have these real life characters interact with my fictional recreation of young Jackie Bouvier.

I also created three mini-narratives that flashbacked to the German Occupation, still so fresh in the minds of French citizens. One was a deliberate homage to Alan Furst, who has made this unique sub-genre his own; another was inspired by photographs in Serge Klarsfeld's landmark reference work, French Children of the Holocaust; while a third allowed me to recreate the joy of Paris' Liberation Day, August 25 1944.

Now I am not making a case that I am in the same league as any of the writers mentioned above, but I loved the experience of writing Paris to Die For because it allowed me to resurrect a place and a time that exists no more. As Woody Allen shows in Midnight in Paris, it is ultimately unprofitable to live in the past. But it is a hell of a lot of fun to write about and--hopefully--read about.

Published on August 02, 2011 06:24

August 1, 2011

Greg Olear talks about publishing, purgatory and never giving up

Greg Olear is an original. He's also the senior editor at the fabulous The Nervous Breakdown , the author of Totally Killer and the amazing Fathermucker, about a day in the life of a stay at home dad. You don't want to miss the hilarious and strange book trailer, either. I begged Greg to write something for the blog, and I'm thrilled with the results. Thanks, thanks, thanks, Greg!

WELCOME TO PUBLISHING PURGATORYThe Waiting is the Hardest Part

Three-and-a-half years ago, when my debut novel, Totally Killer, was making the publishing house rounds, I wrote this piece and sent it to a (minor) literary magazine, hoping to at last see my name in print. The day that the rejection letter came from said lit-mag—you can't make stuff like this up—was the same day I found out I got my book deal. The lesson? Don't give up.

When I was in the apprenticeship phase of my novelist career—and by "apprenticeship" I mean "getting as much lousy writing out of my system as possible"—I had an administrative day job with the Associated Press. The avuncular gentleman who handled the book reviews, knowing of my literary aspirations, would pass along every how-to-get-published guide that crossed his desk. The gyst of those books was that to get in print, you needed an agent. The agent, the books explained, was the bouncer at an exclusive nightclub called Publication, where hobnobbed the Paul Therouxes and the Ian McEwans and the Bret Easton Ellises (Bret Eastons Ellis?)—and where I stood outside, with countless other wordsmith wannabes, waiting beyond the velvet ropes. The key, the books assured me, was to get through the door. Find an agent, and you find a publisher. End of story.

Mind you, I didn't think I needed an agent. My novel, after all, was perfect in every way; its understated brilliance would be obvious to any editor worth her salt. Why should some glorified middleman (or middlewoman, as it were) be entitled to fifteen percent, I reckoned, just because the antiquated system happened to work that way? It was only after investing several paychecks in SASEs that I discovered the problem with this thinking: editors don't read anything—even unequivocal masterpieces like my novel—unless an agent tells them to.

With no choice but to play along, I did what the books instructed: I went out and found myself an agent. And it's a good thing, because, as it happened, I did need one—and not just to forward my manuscript to Random House and HarperCollins. What my agent did was nothing short of alchemy. She took what was a leaden first draft and turned it into…if not gold, then something that doesn't poison small children when used in paint. Then she did one better, selling some editors on the project.

So why is my book not available at Barnes & Noble, you ask? Ah, there is the rub. The how-to-get-published books, it seems, were not entirely straight with me. Agents are not gatekeepers. There is no literary nightclub. For all I know, Bret Easton Ellis and Paul Theroux have never even met.

I'd been led to believe that if an agent sold an editor on the book, that'd be that. Not so. Agent-to-editor is merely the first step in a complicated dance. The editor, once on board, must then pitch the book to senior editors and marketing people at what is known in the industry as the Editorial Meeting but what in my house is playfully nicknamed The Bane of My Existence. It is at the Editorial Meeting where the powers that be decide to eschew cutting-edge first-time fiction for more marketable fare, like Monday Night Jihad, by Denver Broncos placekicker Jason Elam. Four times my novel has made it to the Editorial Meeting, and four times it's been kibboshed. To continue the football motif, I'm like the Buffalo Bills, who went to the Super Bowl four times in a row, only to lose all four times.

Not that this warrants the playing of violins or the rending of garments. There is consolation. There is solace. For one thing, to lose the Super Bowl four times in a row, you have to be pretty good. I'm reasonably certain, at this point, that I am a better novelist than Paris Hilton is a musician. Not that this stopped Warner Brothers from bestowing a record deal upon her. In fact, if Paris Hilton were to write a novel (working title: Paris the Thought), she'd have no trouble finding a publisher—and she'd probably outsell everything this side of What to Expect When You're Expecting. By virtue of being a blonde leggy hotel heiress, Paris Hilton is a brand that can attach to, and sell, anything, from pop records to trade paperbacks to blue movies. I am not, needless to say (and alas), a blonde leggy hotel heiress. My name has neither cachet nor kitsch value. Whatever you think of my product, I am generic, the marketing equivalent of Vintage Cola. And my lack-of-named-ness is why my novel keeps getting killed in committee. Or so I tell myself, as the weeks turn to months, and the rejection letters pile up.

Check that: as the rejection letters slowly pile up. It hasn't actually been forty years of wandering the desert—I'm only thirty-five; old for a ballerina, young for a novelist—but boy does it feel that way. The publishing world moves at so deliberate a pace, Al Gore could make a documentary about it melting. After waiting so long and working so hard, with nothing to sustain me but the manna of an occasional "rave rejection" and blind faith in my writing talent that may turn out to be delusional—I can't even get a short story published! I didn't even get into an MFA program!—I've gone as far as I can go on my own. And lo, there is the Promised Land, in my sights. All I need is the thumbs up from Jehovah (or Jonathan Galassi, not that there's much difference) and I get to cross the River Jordan. Until then, I wait in literary Casablanca. And wait. And wait. And…

How does one cope with Publishing Purgatory? On this subject, the know-it-all how-to-get-published books fall dumb. Successful authors who crank out memoirs about their craft—Stephen King, say—have little to say about my situation, because if they were in my situation, they wouldn't be successful authors, and if they weren't successful authors, they wouldn't be writing memoirs about their craft. Heck, even the Bible, which is supposedly so uplifting, offers little hope; the Promised Land didn't work out so well for Moses.

So where does one turn for guidance? If there is an analog in all of literature, it is found in the nineteenth sonnet of John Milton, of all places. Throughout, and in the ultimate line particularly, the dour DWEM perfectly articulates my close-but-no-cigar anguish:

…thousands at [God's] bidding speed

And post o'er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait.

Milton, of course, was coping with the loss of his eyesight, next to which the loss of Editorial Meeting consensus takes on a decidedly hill-of-beans sort of quality. Still, the Zen lesson intended by the Christian poet is clear: Stay ready, and don't lose hope—the Universe has a plan for you.

Bret Easton Ellis was published at twenty-one because he was supposed to be. I'm where I am because I'm supposed to be. My writing talent will not go to waste! It will just improve with age, like single-malt scotch, digital cameras, Harry S Truman's presidential ranking…and John Milton's writing talent. Paradise Lost—the greatest literary achievement in the English language, it says here—was published in 1677, when its author was almost sixty.

So, while more fortunate men of letters speed and post without rest, I will keep standing and waiting. The publicity people may not be on my side. But time is.

—Greg Olear is the author of the novels Totally Killer and Fathermucker and the editor of Fathermucker: The Blog. He lives with his family in New Paltz, N.Y.

Published on August 01, 2011 09:42

July 29, 2011

Kim Wright talks about Hiding in Plain Sight, and being seen

Kim Wright's wonderful new novel, Hiding in Plain Sight, is about female friendships, marriage, infidelity and how we shape and view our lives. I asked Kim if she'd write something for me, and I'm honored to host her here. Thank you, thank you, Kim!

Hiding in Plain SightBy Kim Wright

In the mystery I'm working on now I've got a character – my bad guy, my villain, my favorite – who brags that he knows how to hide in plain sight. He explains how his father took him quail hunting as a boy and taught him that success wasn't a matter of complicated subterfuge but rather knowing how to blend into your environment so that the birds registered your presence, but didn't perceive it as a threat. It's his method for murder and my method for writing.

Writers have complicated feelings about being seen or unseen. On one level, our profession depends on our ability to observe things without being observed in return. In that way we're like spies, and I spent my childhood, in fact, sitting in a tree in my grandmother's yard wearing a black turtleneck and pretending to be a secret agent. The superpower I most craved was invisibility and recently I've come to understand that this was a common fantasy among children who grew up to be writers. Years later, as a college student determined to master the rhythms of dialogue, I would sit in a mall food court with a notebook, eavesdropping and transcribing conversations.

The realities of writing only make our natural born tendencies toward isolation and sneakiness worse. We work alone. We rarely talk to others. We squirrel away into corners. We mutter. It's pretty close to my childhood dream of invisibility.

And then the book comes out.

All of a sudden, with a speed that seems both jarring and cruel, we're expected to transform ourselves into public characters. While the job of the writer is to write, the job of the author is to tweet, blurb, blog, tour, engage, and promote. Of course we want our books to be successful and all that comes with it. We want to be seen, seen often, and preferably seen on Good Morning America.

But even these frenzied marketing attempts are a snap compared to the other ways in which publication makes us suddenly visible. Because when people read your books, they feel that they know you. More specifically, they believe that your main character is you. I've stood in front of many groups and sat in the circles of many book clubs, fielding the same questions: Is the book autobiographical? Is Elyse you?

In some ways I've invited this assumption, since I set my novel in my own home town and made my heroine a woman who is about my age, also divorced, and someone who furthermore has - as so few people do - brown hair. But I suspect writers go through a variation of this scrutiny even if they set their books in 15th century Japan or 28th century Saturn. We all put our own thoughts into our character's heads, our own fears into their plot twists. We all have one that we identify with most, whether we share surface similarities or whether we deliberately cast our secret selves into the character who least resembles our public persona. The resultant characters are us and not us and there are a thousand different ways to talk about this, different levels of confession for each writer which feel appropriate and true.

Sometimes I think the whole writing-to-publishing process is designed to take people who are half-crazy already and drive them fully insane. Because the first part of the process, writing, requires you to be anonymous, and the second half of the process, publication, requires you to be famous. And when someone stands up at a reading and quotes your own words back to you, it feels like you're not only seen, but exposed.

But it's part of the process, so writers who plan to keep writing learn to deal with it. For me, proclaiming that all of my characters are actually parts of myself - and yes, in many ways, Elyse more than any of them - is my own little ruse for preserving some privacy. If you say there's no mystery, then no one tries to solve the mystery. In the meantime I struggle with the issue of someone who simultaneously wants to be seen and unseen. And, like my fictional bad boy, I've opted to hide in plain sight.

Published on July 29, 2011 14:20

Carey Wallace talks about singing, inspiration and The Blind Contessa

I first heard Carey Wallace at the fabulous Word bookstore in Brooklyn, where we were doing a group reading. Not only did she read from her exquisite new book, The Blind Contessa's New Machine, but she sat in front of a keyboard and she sang. I was so gripped, I forgot my own stage nerves. I could have listened to her read and sing forever. I'm thrilled to have Carrie here.

I had the rare pleasure of hearing you sing at Word in Brooklyn and I came up and told you afterwards how haunted I felt listening. So tell me about crafting songs. How is it different for you than writing a novel?

Songs and books come to me in almost completely opposite ways. In both cases, I have a strong sense that I'm discovering something, rather than building it – that the process is one of searching for something that's already there, rather than gathering pieces, laying plans, and hammering it all together. But because books take such extended concentration, I've followed a practice of discipline in writing for all of my adult life: I write for two hours every working day, whether I have any desire to or not. Songs, on the other hand, tend to arrive unbidden. I don't go looking for them, I just take them as they come, and when they do, I write them anywhere I happen to be, over the course of several days, mostly by singing the pieces I've got over and over in my head until the missing lines or sections emerge. Once the writing process is finished, the reaction you get to songs or books is also really different: even people who've loved you for years tend to blanch when you mention you've got a novel they might like to read, but total strangers want to hear your new song.

Each song in your gorgeous CD refers to a literary work. What made you choose the books you chose?

Since my songwriting process is so mystical, the books actually seemed to choose me. When I wrote them, last summer, I was living in Michigan, caring for my mother in the small town I grew up in, as my first novel came out. The songs, and the books, that emerged from that time were about family, especially mothers, about hope for a world beyond this one, and about how the worlds we've left behind haunt us. The books all in some way intersected with these themes, and I mined them for images as I explored those themes in my own life.

The Blind Contessa, your novel, is this achingly beautiful novel about love and imagination. What sparked the idea for this novel?

Carbon paper. I was actually writing an early draft of a noir novel set in Detroit, and wanted to make sure that the carbon paper I planned to use in it wasn't an anachronism. When I looked up the advent of carbon paper, I discovered the story of the invention of the typewriter, which was invented at the same time by the same man (carbon paper was used in the original machine to make the image of a letter on the page). The elements of the story: a blind woman, an eccentric inventor, the hint of love triangles, and the typewriter itself seemed clearly the foundation of a novel.

What was it like writing a first novel? How is it different from your writing life now?

There are a number of candidates for my first novel: a fifty-page tome, heavily influenced by Dumas and full of flounces and French names, that I produced in the fifth grade; a full-length novel about a kid who sells his parents house, and takes the money and four of his friends to Disneyland that I wrote in college; and Choose, a forking paths novel about predestination and free will that was printed in an extremely limited run by a now-defunct press in Detroit in 2006. By almost no definition but the commercial one is The Blind Contessa's New Machine really my first novel. Interestingly, in the golden age of American publishing, publishers generally recognized that it took three full-length novels for a writer to come into their own, and, because those publishers didn't face the same financial constraints as publishers today, they were committed to nurturing their authors through that process. It's stunning to see how many significant novels are the third book of an author who was nurtured through this process, among them The Great Gatsby and A Farewell To Arms – and how little resemblance these mature books bear to the first novels that preceded them (This Side of Paradise and Torrents of Spring). I get quite sad about what great books we may be losing today because writers are now expected to accomplish their apprenticeships on their own. In some cases, the fight sharpens us and makes us stronger. But I believe many of the literary treasures that emerged from previous generations might never have seen the light, or perhaps never have been written at all, in our current climate.

What's obsessing you now?

Hydroelectricity in Paraguay. A good friend of mine is about to defend her brilliant dissertation, which I'm now editing, on the topic, and it's actually incredibly fascinating: Paraguay shares the world's most productive hydroelectric dam with Brazil, which is something along the lines of New York state damming Niagara Falls and then trying to split the electricity equally with Rhode Island. The story has all kinds of other amazing details—a priest who becomes president, hidden caches of torture records—but also wide implications for the pressing question of what it means to be a state in today's shifting global world, and the future of negotiations around borders, energy, and the economy throughout Latin America.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

How can your readers get a copy of Songs About Books for themselves?

First of all, Songs About Books isn't for sale – it's a gift, part of the celebration surrounding the paperback release of The Blind Contessa's New Machine. Anyone who wants to can download all the tracks for free athttp://www.careywallace.com/songsabou.... And if they'd like a super-beautiful actual CD, which is full of antique photographs of people holding books, they can send me something in trade. So far I've traded CDs for everything from translations of Italian poetry, to a box of pasta and homemade marinara sauce, to a single perfect rose from my favorite flower-shop owner. (Trade directions can also be found at the address above.) In September, I'm going to begin posting the trades in a gallery on my website, to share all the beautiful things, but also to create connections between the people who made them – so if you're an artist yourself of any kind, be sure to include your website with whatever you send, and I'll make sure to link to it.

Published on July 29, 2011 14:18

Carrie Wallace talks about singing, inspiration and The Blind Contessa

I first heard Carey Wallace at the fabulous Word bookstore in Brooklyn, where we were doing a group reading. Not only did she read from her exquisite new book, The Blind Contessa's New Machine, but she sat in front of a keyboard and she sang. I was so gripped, I forgot my own stage nerves. I could have listened to her read and sing forever. I'm thrilled to have Carrie here.

I had the rare pleasure of hearing you sing at Word in Brooklyn and I came up and told you afterwards how haunted I felt listening. So tell me about crafting songs. How is it different for you than writing a novel?

Songs and books come to me in almost completely opposite ways. In both cases, I have a strong sense that I'm discovering something, rather than building it – that the process is one of searching for something that's already there, rather than gathering pieces, laying plans, and hammering it all together. But because books take such extended concentration, I've followed a practice of discipline in writing for all of my adult life: I write for two hours every working day, whether I have any desire to or not. Songs, on the other hand, tend to arrive unbidden. I don't go looking for them, I just take them as they come, and when they do, I write them anywhere I happen to be, over the course of several days, mostly by singing the pieces I've got over and over in my head until the missing lines or sections emerge. Once the writing process is finished, the reaction you get to songs or books is also really different: even people who've loved you for years tend to blanch when you mention you've got a novel they might like to read, but total strangers want to hear your new song.

Each song in your gorgeous CD refers to a literary work. What made you choose the books you chose?

Since my songwriting process is so mystical, the books actually seemed to choose me. When I wrote them, last summer, I was living in Michigan, caring for my mother in the small town I grew up in, as my first novel came out. The songs, and the books, that emerged from that time were about family, especially mothers, about hope for a world beyond this one, and about how the worlds we've left behind haunt us. The books all in some way intersected with these themes, and I mined them for images as I explored those themes in my own life.

The Blind Contessa, your novel, is this achingly beautiful novel about love and imagination. What sparked the idea for this novel?

Carbon paper. I was actually writing an early draft of a noir novel set in Detroit, and wanted to make sure that the carbon paper I planned to use in it wasn't an anachronism. When I looked up the advent of carbon paper, I discovered the story of the invention of the typewriter, which was invented at the same time by the same man (carbon paper was used in the original machine to make the image of a letter on the page). The elements of the story: a blind woman, an eccentric inventor, the hint of love triangles, and the typewriter itself seemed clearly the foundation of a novel.

What was it like writing a first novel? How is it different from your writing life now?

There are a number of candidates for my first novel: a fifty-page tome, heavily influenced by Dumas and full of flounces and French names, that I produced in the fifth grade; a full-length novel about a kid who sells his parents house, and takes the money and four of his friends to Disneyland that I wrote in college; and Choose, a forking paths novel about predestination and free will that was printed in an extremely limited run by a now-defunct press in Detroit in 2006. By almost no definition but the commercial one is The Blind Contessa's New Machine really my first novel. Interestingly, in the golden age of American publishing, publishers generally recognized that it took three full-length novels for a writer to come into their own, and, because those publishers didn't face the same financial constraints as publishers today, they were committed to nurturing their authors through that process. It's stunning to see how many significant novels are the third book of an author who was nurtured through this process, among them The Great Gatsby and A Farewell To Arms – and how little resemblance these mature books bear to the first novels that preceded them (This Side of Paradise and Torrents of Spring). I get quite sad about what great books we may be losing today because writers are now expected to accomplish their apprenticeships on their own. In some cases, the fight sharpens us and makes us stronger. But I believe many of the literary treasures that emerged from previous generations might never have seen the light, or perhaps never have been written at all, in our current climate.

What's obsessing you now?

Hydroelectricity in Paraguay. A good friend of mine is about to defend her brilliant dissertation, which I'm now editing, on the topic, and it's actually incredibly fascinating: Paraguay shares the world's most productive hydroelectric dam with Brazil, which is something along the lines of New York state damming Niagara Falls and then trying to split the electricity equally with Rhode Island. The story has all kinds of other amazing details—a priest who becomes president, hidden caches of torture records—but also wide implications for the pressing question of what it means to be a state in today's shifting global world, and the future of negotiations around borders, energy, and the economy throughout Latin America.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

How can your readers get a copy of Songs About Books for themselves?

First of all, Songs About Books isn't for sale – it's a gift, part of the celebration surrounding the paperback release of The Blind Contessa's New Machine. Anyone who wants to can download all the tracks for free athttp://www.careywallace.com/songsabou.... And if they'd like a super-beautiful actual CD, which is full of antique photographs of people holding books, they can send me something in trade. So far I've traded CDs for everything from translations of Italian poetry, to a box of pasta and homemade marinara sauce, to a single perfect rose from my favorite flower-shop owner. (Trade directions can also be found at the address above.) In September, I'm going to begin posting the trades in a gallery on my website, to share all the beautiful things, but also to create connections between the people who made them – so if you're an artist yourself of any kind, be sure to include your website with whatever you send, and I'll make sure to link to it.

Published on July 29, 2011 14:18

Publishing not as Usual Part Two: Lou Aronica Talks about The Fiction Imprint

I've already run a piece about two writers who are now going to publish with the Fiction Studio Imprint, but now I have the man behind the The Fiction Studio Imprint , New York Times bestselling author, former publisher of Avon Books and Berkley Books, Lou Aronica. An invitation only imprint, The Fiction Studio publishes books in paperback and e-book format and it represents a revolutionary new way of publishing. Aronica,created this new frontier, a gathering of "ambitious wildly creative writers." To read the whole story, look here .

I'm thrilled to have Lou here.

You have a fascinating background, coming from the world of traditional publishing. Why don't you think this model works anymore? And can you tell readers something about the way Fiction Studio Imprint changes the rules?

I'm not saying that the traditional publishing model doesn't work anymore. What I'm saying is that it doesn't work for enough people any longer. I'm going to sound like an old codger with this, but back in the day, when I was a publisher at a big house, we offered writers a decent up-front income, careful editorial attention, and appropriately scaled marketing support (after having walked six miles uphill in the snow to get to work). When a traditional house is still willing to do this, it works very well for a writer. However, that combination of financial, editorial, and marketing is increasingly rare.

Meanwhile, the market has shifted in the writer's direction. Manufacturing and distribution – huge barriers to entry in the past – aren't an impediment as long as you can accept the online bookselling world as your marketplace. Many writers have visions of their books in bookstores all over the country. That's a very appealing vision, but you need to be willing to accept the baggage that comes with it in the form of heavy returns, pigeonholing, and publishers turning down your next book because the previous one didn't sell enough to keep the booksellers interested.

When I started Fiction Studio Books, I established a relationship with our distributor, National Book Network, that allows for bookstore distribution. I knew I was going to hold that in reserve, though. Because the focus of the program is on developing audiences for writers, I felt that the development had to happen on the digital side. Having the ability to distribute into the physical retail market means that if a book takes off to the point where we would feel comfortable with a physical distribution, we can do it, but we've had some very successful books already and I still haven't hit that point. By focusing on the digital side, Fiction Studio can publish a much wider range of fiction and take the time necessary to build an audience for a book.

The most significant way in which Fiction Studio changes the rules is that it is essentially a writer's collective. I'm the curator – I need to love every book we publish – and I make my thirty-plus years of publishing experience available to every writer on the list, but the writer remains in control of the publication and keeps the overwhelming share of the publishing income. I set it up this way because I wanted Fiction Studio to be a community of writers working together and sharing ideas. We've already gotten some nice results from that.

You published your novel Blue yourself—and made it a bestseller. I speak for every writer out there: how, how, how, did you do this???

The reason I wanted to publish Blue myself was that I knew it wasn't a novel that publishers could easily position. It's a father-daughter novel, but it's also a fantasy novel. One viewpoint character is a man in his early forties, another is his fourteen-year-old, largely estranged daughter, and the third is the twenty-year-old queen from the bedtime story world they created when the daughter was much younger. It's about the affect of divorce, but it's also about the value of imagination. I'd spent six years writing it, and I could imagine every publisher saying, "Yes, it's a nice story, but where do we put it in the store?" I knew there was an audience for it, though, and I felt that I needed to try to find it for myself.

Because I wasn't concerned about physical distribution, I didn't have to worry about the book selling in the first two weeks, and I didn't have to worry about where the book was going to be placed. That allowed me to be more patient with the publication and to cast a wider net in trying to draw attention to it. The first step was getting blog reviewers to take it under their wings. I pitched three different markets – the general fiction readership, the sf/fantasy readership, and the teen fantasy readership, and I got very encouraging review attention from bloggers in all three areas. I received about seventy reviews for the book and only a couple of them suggested that I consider a career in the fast food industry.

Once I'd established the novel's credibility, I decided to drop the e-book price dramatically. I couldn't do anything about the print price because those books had to be printed, but I realized that I'd already spent all the money on e-book production that I needed to spend (copyediting, proofreading, cover design, conversion, etc.). If I looked at that expense as a "sunk cost," everything I made thereafter was profit. That's the thing about the e-book business: it doesn't cost you any more to sell twenty thousand than it does to sell twenty. If I could take price out of the buying decision for the reader, maybe I could sell many, many more at $2.99 than I was selling at $9.99. That's when the book took off. I think the combination of the great reviews and the low price made it easy for readers to download. I don't think either by itself would have done the job.

Essentially, I used a very old technique. I saw the first life of the e-book as the "hardcover" to gather reviews. I then used the cred those reviews offered to sell the lower-priced edition, the "paperback reprint" if you will.

One thing you said, which I loved, was that writers are now getting second and even 10th chances to get their work out there in front of the public, which means there are a lot of sharks out there. Do you have any caveats for writers who want to go a non-traditional route?

While the barriers to entry are much lower than they've ever been, publishing is still a foreign experience for most writers. Many of them will seek help, and some people will try to take advantage of them. My feeling is that a writer should never pay a fee for publication. There are genuine costs involved in getting a book into the market. You might need a professional editor. You will definitely need a professional copyeditor. You will need a professional proofreader. You will need a professional cover designer (notice the repeated use of the word "professional" here; this isn't a cute literary device – there's an enormous difference in working with experienced professionals). You will need pages designed and composed for the print edition, and you will need a conversion house to create the e-book file. You will need to print copies for marketing purposes and spend the money to mail those copies out. You may need a marketing professional to help you promote the book. All of those are legitimate expenses and there are many excellent freelancers out there providing these services. However, any publisher charging a fee beyond the cost paid to the freelancer isn't, in my opinion, a real publisher. If a publisher is making money on a publication before the author sells a single copy, it's difficult to believe that this publisher is working in the writer's best interests.

Your imprint is by invitation only. How are you finding your writers? And what should a writer who wants to be noticed by you do?

The reason the imprint is invitation-only is that I don't make any money on a publication unless the books sell. Therefore, I need to believe that the author is going to be an extremely active partner in the publication. This isn't something I can identify simply by reading a manuscript. Therefore, I look for recommendations from people in the industry, writers who strike up a correspondence with me, tips from the guy at the farmer's market, that sort of thing. I'm going to go over my title target for the first year, so this method seems to be working (and thank you, Caroline, for sending two fabulous writers in my direction).

If someone wants to get my attention outside of these methods (I've heard that the guy at the farmer's market isn't above taking a little "seed money," if you know what I mean), they need to show a real interest in the process. I want to work with writers who are interested in writing and publishing. You can't really be a valuable member of the collective if you don't care about how things work in this industry. Then, of course, you need to get my attention with the writing itself. I'm far more interested in characters and character evolution than I am in plot or setting.

What's next on the horizon for the Fiction Studio? In other words, what's obsessing you about the book business?I'm hugely optimistic about the business right now, more than I have been in a very long time. Digital publishing is liberating in so many ways. Still, the publishing world is changing daily, and what's working right now will seem quaint in a few months. My real obsession at the moment is sustainability. How does a writer find an audience and keep that audience? Much of the energy in the business right now is coming from pricing and the growth of the user base (all those people getting their first Kindles, Nooks, iPads, Sony Readers, etc.). That allows for a certain level of success to come simply from seizing opportunities. However, sustainable success is going to come from staying in readers' minds. How do you capture the moment while working for the long-term. That's what gets me up very early in the morning.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

I think you nailed it.

Published on July 29, 2011 14:17

July 26, 2011

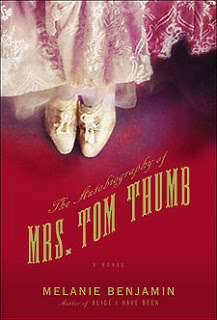

Melanie Benjamin talks about Mrs. Tom Thumb

I first interviewed Melanie Benjamin for her exquisite novel Alice, I Have Been, about the real Alice in Wonderland. When I was on my book tour, and in the middle of the worst blizzard in Chicago, not only did Melanie come out to hear me read, she drove me back to my bed and breakfast AND she waited until I got in, which was a good thing, because the door would not open with my key. That's an amazing person! I couldn't wait to read Mrs. Tom Thumb, because I had loved Alice, I have Been so much, and I was completely knocked out by the story. (It's already an August Indie Pick.) Lush, beautifully written, filled with drama and one one of the most vividly interesting women around, Mrs. Tom Thumb is just spectacular.

I'm honored to have Melanie here--she's just a wonderful writer, and a terrific friend.

Where did the idea for Mrs. Tom Thumb come from?

I was half-way through the 2nd book of my contract when I knew it was a dead end; I couldn't finish it. Yet I had a deadline mere months away! Before I told my editor, and gave her a heart attack, I knew I'd better come up with another idea and maybe a chapter or two. So I started Googling like mad, paging through lists and lists of historical events, figures, women - I did know the time period that I wanted to write, as well as the setting. Since ALICE was set in England, I wanted my next one to be an American story. On one of those lists I saw the name "Lavinia Warren Stratton - aka Mrs. Tom Thumb." It rang a bell and I remembered that she was in a small scene in one of my favorite books, E. L. Doctorow's RAGTIME. She was feisty, even in his book. So I started researching her and was immediately enchanted by her story and her voice.

As far as what she has to teach us - it's both an uplifting, and cautionary, story. Uplifting in that she truly never saw any limits, any obstacles - but cautionary in that she started to believe her own hype, in a way. She very willingly traded on her stature in order to see the world, but then somehow deluded herself into thinking others didn't see her, first and foremost, as a dwarf.

Can you talk about your writing process?

When I write, I really try to "become" the protagonist; it's the only way I can capture the voice. So Vinnie's voice was entirely different from Alice's, and thus, the book has an entirely different quality. ALICE was more lyrical, more dreamy - befitting the ALICE IN WONDERLAND books. MRS. TOM THUMB has a verve, a pulse - I think it's a uniquely American story, written in a uniquely American style. As Vinnie herself would have told you, she was a proud patriot, and I truly tried to capture something of that in the book. As far as what surprised me - her relationship with Barnum. That became the driving point of the book; I began to understand he was the only person in her life with a personality as big as her own. And I'm never consciously aware of "deciding" on a structure - I just let the book appear to me as it wants to.

As someone who was drowning in research this year, I have to ask you, how do you do it?

Research is fun! I love immersing myself in history books, finding amazing websites (and there are so many, as this book takes place against a rich panoply of American history). The only pitfall of research is spending too much time in it, and forgetting to tell the story! The characters and their relationships have always to be the main focus of the book; the historical details are important and rich, but they can't overwhelm the characters and their stories.

Come on, tell us about your writing life!

My writing life, now that I have one book out (ALICE I HAVE BEEN), one just out (THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF MRS. TOM THUMB), and one I just turned into my editor (for publication next year), is much more difficult than it used to be! I have to be much more disciplined, giving a certain amount of time over to paperwork, busy work - work, in other words! Which means I have to carve out my writing time, whereas before, my entire day was devoted only to writing. So in the mornings I usually do the busy work; in the afternoons, I write. Many of my evenings are now taken up with calling or SKYPING with book clubs, which is a joy.

What's up next for you?

Right now, I'm drawn to a couple of eras; one is pre-Civil War America, the other is the early days of Hollywood. I'm going back and forth, but keeping an eye open for anything else that might inspire me. I have a bit of time before I have to start the next book - the one that will be out in 2 years.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

You should have asked me what my favorite part of being an author is - because I would have answered, "Meeting fellow authors like you!"

Published on July 26, 2011 14:34