Caroline Leavitt's Blog, page 2

March 17, 2022

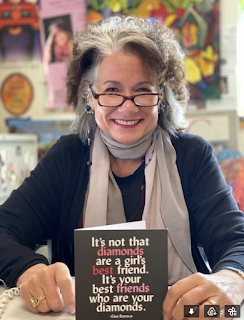

Women are rewriting their own story! Come see how in Gina Barreca's hilarious collection of flash fiction from some of the fiercest women around: FAST FIERCE WOMEN

No one writes a funnier bio than Gina herself, So here it is:

Gina Barreca has appeared, often as a repeat guest, on 20/20, The Today Show, CNN, the BBC, NPR and, yes, on Oprah to discuss gender, power, politics, and humor. Her earlier books include the bestselling They Used to Call Me Snow White But I Drifted: Women’s Strategic Use of Humor, It’s Not That I’m Bitter, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying About Visible Panty Lines and Conquered the World, If You Lean In, Will Men Just Look Down Your Blouse, and Babes in Boyland: A Personal History of Coeducation in the Ivy League. Of the other six books she’s written or co-written, several have been translated into to other languages–including Chinese, Spanish, Japanese, Portuguese and German. Called “smart and funny” by People magazine and “Very, very funny. For a woman,” by Dave Barry, Gina was deemed a “feminist humor maven” by Ms. Magazine. Novelist Wally Lamb said “Barreca’s prose, in equal measures, is hilarious and humane.” Her latest project is a book on loneliness that will be released in 2020!

Gina’s award-winning weekly columns from The Hartford Courant are now distributed internationally by the Tribune Co.; her blog for Psychology Today has well over 6 million views. Gina’s work has appeared in most major publications, including The New York Times, The Independent of London, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Cosmopolitan, and The Harvard Business Review. Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Connecticut, Gina’s also the winner of UConn’s highest award for excellence in teaching. She’s delivered keynotes at events organized by national organizations in the U.S. and abroad, including Women In Federal Law Enforcement, Chautauqua, The Smithsonian, the Women in Science, Dentistry, Osteopathy & Medicine, the American Payroll Association, the National Association of Independent Schools, and the National Speaker’s Association, to name a few.

Her B.A. is from Dartmouth College, where she was the first woman to be named Alumni Scholar and the first alumna to have her personal papers requested by the Rauner Special Collections Library at the College. Her M.A. is from NewHall/Murry Edwards College at Cambridge University, where she was a Reynold’s Fellow. Her Ph.D. is from the City University of New York, where she lived close to a very good delicatessen. A member of the Friars’ Club, holder of a number of honorary degrees, and honored by the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, Gina can be found in the Library of Congress or in the make-up aisle of Walgreens. She grew up in Brooklyn and Long Island but now lives with her husband in Storrs, CT. Go figure.

And what I need to add is that Gina is my adored friend. I'd do anything for her. Well, maybe not eat a mayonnaise sandwich, but you know what I mean.

You and I have talked so much about how humor saves us. But so does being fierce! Can you define what fierce means to you, and we ALL know it does not mean being a bitch, which is a word used to denigrate rather than empower? And can you tell us how the idea for Fast Fierce Women began?Every time a woman opens her mouth and anything apart from a cooing noise or a compliment comes out, she’s called a “bitch.” I don’t like the word “bitch” and so I don’t use it--and I ask my students not to use it around me, not even as way of congratulating or praising each other. But “tough"? That’s a good word. Tough broads, tough gals, touch chicks (although “chicks" only worked until around 1982) are all seriously great descriptions. They connote resilience, resistance, and a refusal to stick to the code of benign, simpering femininity. Fierce is the BEST word, though, because it conveys an active desire not to settle for less than we’ve always wanted, which is a good time and a fair fight. I am absolutely loving all the books you do with flash creative NON fiction. I’ve never actually DONE flash fiction before you asked me, too, and I love the punch it really does pack. How did you come to decide on this format?

All great writing holds a mirror up to life and the short form holds up a compact mirror: you see a miniature, an accurate but scaled down weekly columns for than 20 years and, like you, blog for PSYCHOLOGY TODAY. I enjoy the short form; it’s the right cut for my weird shape (and what woman doesn’t think her shape is weird? That’s something for another collection).

Tell us about some of your fave pieces in the collection? And how hard was it to decide what to pick?!

Every essay is about strength, focused power, passion, and determined intelligence, often coupled often with instinct, tenacity, persistence, resilience, rage, and inflexibility. These themes or ideas or stories are often coupled with humor, and deal with friendship, loyalty, talent and community—what’s not to like? Some of the emerging writers in the book, young women who have never seen their words in print before, have written impressive pieces: “Black People Don’t Do This” by Ashaleigh Carrington, a former student, is both funny and heartbreaking—talking about going to therapy with her middle-aged shrink’s “white noise” going in the background, but her own wish to make her life better determining her commitment to mental stability; Nicole Catarino writes about a battle with OCD and, again, tells her story with ferocity and without self-diminishment—and also with humor. There are stories about flight attendants who finally got the revenge on the jerk passenger we’d all like to get, and stories about first jobs, old sex, and love—so many stories about love, we discover that fierce love is the most enduring kind of love there is. I’m proud of every piece, as different as they are—or maybe because they are so different from one another.

We’ve also talked about how with women, part of the reason we all go to the ladies’ room together, is to talk, to laugh. Even when we go alone, we start up convos with whoever is there, and soon become fast friends. I have always felt that meeting you was like Friends at First Sight. I just KNEW immediately. And the more we know each other, the stronger our friendship gets. My husband often says that his best friends are women—because they go deeper, they are more honest, more real, and I was wondering why do you think the friendships are different?

Every woman I know believes her own friendships are endowed with a kind of secret significance. I certainly do—my friends keep me alive. Look, I’m not married to my best friend. I’m married to my husband. He’s a man I adore but he’s not my best friend. For that I am fantastically grateful. One of life’s great gifts is that there’s no taboo against having multiple best friends. You don’t have to go on reality television or into family court to explain or defend yourself. Nobody says “What? You’ve had twenty friends in twenty years? That’s terrible. How could you?” And that’s because friends are people you’re supposed to have in your life—the more the better. Nobody says that about spouses.When we’re with our women friends, we believe that we are in extraordinary company; that’s how I felt about meeting you, Caroline, right from the beginning. Making us feel rare and prized, our friends capture our imagination and offer us perspective. They remind us not only who we are, but also why we’re significant. Friendships inspire us. They allow us to express ourselves, even when we can’t stand the self we’re expressing or when we’re so far from our true selves that we turn to our friends to bring us back, as if we’d put our personalities in pawn and gave our friends the receipt for safekeeping—as if they were the ones we trusted, more than we trust ourselves.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

I wish I had smarter and more wide-ranging answers to this insightful questions. I’m scared by the news, which makes me rock back-and-forth, worrying about whether I should spend money trying to arm Ukrainian soldiers, or install just another generator and hoard more seltzer—I feel useless and ignorant. My greatest fear in life is being useless. I feel at my lowest when I feel as if I am trying my best and getting nowhere. When that feeling comes around, I go all self-torturing. Nothing I have done is enough, nothing I can do will be enough, who I am is absurd—and that’s why the question about friendship is crucial. When I feel this way, I turn to my friends and they help, lending me their own perspective when mine is wobbly.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

You asked ALL the good questions. You are kind and generous, and I am lucky to know you. THANKS DOLL!!

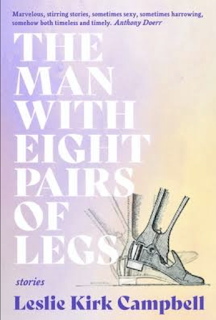

Leslie Kirk Campbell, winner of the Mary McCarthy Prize for Short Fiction talks about her astounding new collection, THE MAN WITH EIGHT PAIRS OF LEGS, longings, settings, and so much more

Leslie Kirk Campbell is the author of Journey Into Motherhood: Writing Your Way into Self-discovery. Her latest stunning collection of stories, The Man With Eight Pairs of Legs, has just come out. Visit her and learn more at www.lesliekirkcampbell.com

I always think that writers are haunted into writing their stories, or looking to write their way into an answer for some questions they have. Was it this way for you?

I am a writer richer in ideas than in characters. These ideas often arise from a question that is unexpectedly provoked by an image, a movement, a sound, or a dream. My story “Nightlight,” for example, arose from a vivid dream I had in which a middle-class woman, a wife, is looking out her bay window, surprised to see her husband walking away from her down the street, his arm around a young homeless man, the two almost glowing as the sun rises in front of them. Why did this man leave? I wanted to know. What drove him to make that decision? On another occasion, I heard the sound of someone cutting trees for hours while I worked in the old convent where I often go to write. I walked up the street and saw a woman standing alone at the top of her steep drive. I felt her sadness deep in my gut along with the sadness of the trees lying now in pieces on the ground. What sadness, I wondered, caused this woman to slaughter so many beautiful trees? I wrote “Tasmanians” to try to answer that question.

Story after story in THE MAN WITH EIGHT PAIRS OF LEGS was driven by my curiosity. What would it be like not to have legs? I wondered after seeing a row of fascinating prosthetics in a TED talk. And then, what makes a human human anyway? (“The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs”) How can a woman still love her philandering husband? (“Thunder in Illinois”). What might drive an abused woman to kill? (“Overture”) Each question, of course, connects with some key aspect of my own emotional landscape.

Your work made me think of that great book The Body Keeps the Score, about how our memories react to our memories, how the truth of what happened might be suppressed in our minds, but it always comes out in our bodies. Can you talk about that for us please?

The body does keep the score, as much as boulders along the sea or in the foothills hold the marks of tides, snow and wind. My own body has been repeatedly objectified, cut into by surgeons, its kidney bruised, an arm fractured, the body broken in half in a car accident. It has been assaulted, embraced, touched, and invaded with the threat of death. The body remembers.

That same body gave natural birth to two ten-pound babies (without epidurals), ran varsity track, and spent years studying modern dance, seeing itself in a wall of mirrors. I didn’t realize as I was writing these first stories of mine, that the body was so prominent in them. It took someone else to point out what I hadn’t seen. Over and over, as I attempted to write fiction, my body had been talking to me.

I believe in the emotional intelligence of the body, in the molecules of emotion. I believe we privilege the mind at the expense of listening to our own bodies. My body IS my story and the holder of my stories over time – even, it turns out to a time before I was born.

My maternal side of the family is Jewish, and immigrated through Ellis Island in the late 1800s. A couple decades ago, I went to the small town in Germany where my husband grew up. One night, on a stroll through his town, he pointed to a row of apartment buildings and said, in a neutral voice, “That’s where Kristallnacht took place.” Suddenly overcome, I sobbed sadness relentlessly in his arms. No one in my family had lived through WWII, but there it was, the grief of my people hidden, until then, inside my body. The body remembers.

My characters, too, are marked by their pasts and continue to be marked in present time: bruises that never totally disappear, scars, lesions, heroin tracks. In the “The Hermit’s Tattoo,” the main character tries to erase a tattoo with the name of a childhood friend he once loved. He rubs his skin raw with salabrasion for months, but her name is still there. For Mariam, the protagonist in “Tasmanians.” marks from her past are invisible, yet she feels the ancestral pain of genocide burning on her skin, as real as the fires that burned her grandmother’s family.

“City of Angels” arrived almost in one piece as I unconsciously repeated a particular movement in an improv class. We hold memories along our spines, in our groin, within the softest part of our wrists. I don’t believe that the brain is a closed container; it leaks and spreads, the nervous system reaching everywhere in the body with its rivers and tributaries.

Writing this first book of fiction, I discovered that to really know my characters I had to get inside their physical bodies. I did not want to simply be an authorial witness to their actions. I wanted to rummage around inside them, feel their heat, their aches, listen to their blood circulating – to feel in my body what it feels like to be them.

There is such a deep sense of longing in the stories, that I was wondering – what makes you long?

Perhaps I am a victim of my own restlessness. I lived in six different cities and went to ten different schools by the time I was 18. I longed to have a home like my friends who had lived in the same house since they were born. I was a song leader in high school cheering on the teams, but would imagine myself a prostitute in some foreign country. I was a ‘good’ girl, but I longed to be bad. I realized in my late 20s how male-identified I was and longed to know, finally, who I was as a woman.

At one point I was going to call my collection, Exit Stratgies, when I realized all my main characters seemed bent on escaping some form of imprisonment, whether literally, like the abused woman in “Overture,” or figuratively, from something in their past. Llyn and Grady in “Triptych” are refugees from Kentucky and New Orleans; Reiner in “Nightlight” is a refugee from his family farm in a small German town, and now wants to escape the mundanity of a middle-class job and marriage. My characters seem to seek something other than what they have, often taking dangerous risks to live out their passions, or to quell them.

I’m always curious (because I write novels, not short story collections) how writers decide which story goes first. Which one goes last? What was that process like for you?

When I started writing fiction in my late fifties, I simply wrote the stories I needed to write without any thought of a book. I used these first few stories to cut my teeth on fiction. But once I realized I had enough stories for a collection, and discovered a theme that could unify them, I had to come up with an order. I obsessively made lists in columns. Which ones were in first person, which in third? Which had a male protagonist and which a female? Where is the setting? Which ones are long and which short? Which ones ended with despair, which with hope? I didn’t want any two sequential stories to be too similar.

I had six long short stories and one short short. So I wrote a second one to balance things out. I put one in the first half of the book and one in the second half as a relief from the longer stories. I wanted this collection to be an orchestration, just as I did with each individual story, with variation of movement, texture, and feel. I chose to start with my title story, which I felt would be a great introduction to the collection’s emphasis on the body and longing for something else. I knew I wanted to end the collection on a very strong note. I knew, from attending more of my share of football games, that even after dazzling plays – passes, runs and interceptions – resulting in touchdowns along the way, how dejected I feel if my team ends in defeat. Filing out of the stadium, the exalting moments are forgotten. I needed my last story to be a winner. I chose “Triptych.” I wanted the reader to end their journey with a feeling of love, compassion, and hope.

You’ve been praised so highly for your prose – and rightly so – that I wanted to ask, do you read your word aloud to hear it as well as see it?

Yes, I do. In fact, I record each story and listen back with my eyes closed. I care, perhaps obsessively, about the music of the sentences, each paragraph a movement in a musical composition. I began as a poet. I wrote my first poem to the ocean in Capitola when I was ten, amazed that words could capture my unspeakable feelings of grandeur and awe. In college, I studied poetry from Spain, Britain, France, then traveled through Asia for a year picking up poetry books in every country, got an MA in poetry, studying modern Italian poetry at the Universita di Firenze. As a result, I understand the power of each sound in language, the magic of surprise juxtapositions. I’ve trained students to know what a poet knows about writing as a foundation for their writing in any form for nearly forty years. An image, a metaphor, a phrase or sentence can be thrilling to read, and I want it to be. I want the language to live on the page, it’s music – rhymes and rhythms, its silences, its musical scoring and orchestration. Language is the writer’s medium, just as clay is for the ceramicist, stone for the sculptor, and the body for the dancer. Too often, perhaps, writers take language for granted. But for me it is essential to love language like a poet, to be aware of its natural resources, to feel its exuberance. This is the kind of literature I get excited reading. Rhyme is not just the ‘cat in the hat’. In my stories there are echoes of idea, theme, and image, as well as sounds. I love this kind of layering and relish creating it, although it takes a long time…

What’s obsessing you now and why?

I am currently working on a second collection called Free Radicals. What I am exploring with these stories is the outlaw, the passionate outlier, and the meaning of freedom. I am re-reading Hannah Arendt on totalitarianism and reading Maggie Nelson’s On Freedom. In the long story Lilith that is the ground story for the collection, a Welsh woman wanders freely from place to place, making temporary friends along the way. As poor as she is, she seems not to have a care in the world. But how free is she? What has she lost? What has she gained? What about the love between a Nicaraguan landowner and a Sandinista revolutionary? A lesbian in a homophobic society? Is the lesbian free once she is allowed to get married (a kind of bondage) or was she freer as an outlaw? (I saw Thelma and Louise again recently, which also begs this question.). We are living through a time of angst around this question. What makes one person feel free, may injure someone else. Does anyone really have freewill?

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

Readers have commented on the richness of my stories’ settings and the way they are often grounded in a particular time in history.

Everything happens in a place, and that place cannot be separated from the characters, whether it is a city or a small room with mosquito nets over the bed. I am a firm believer in the power of sensory detail: smell, sound, touch. Together these details create a fully dimensional world. The small-town Colorado setting of “The Man with Eight Pairs of Legs” feels critical to the story of Harriet and Callahan with its bounty of churches (the “good”) and prisons (the “bad”) and its dramatically beautiful mountains and gorges. In “The Hermit’s Tattoo,” the wild fires arrive in sheets over the rolling hills. In each story, there is strong interplay between the character and the place they are in. These descriptive details invite the reader to thoroughly inhabit the worlds I have created for them – to smell the eucalyptus tar along with Mariam in “Tasmanains;” reading “City of Angels,” to feel the salt air and sunlight on their skin.

I am almost organically interested in the reality of history, of social context, of the way a character’s personal triumphs and tribulations do not occur in a vacuum, but within the fabric of a cultural and political era. What is happening beyond the confines of the characters’ individual lives puts pressure on their personal conflicts and choices. In some cases, it is a particular time in history I have lived through like the AIDS epidemic in the 80s, or I will spend hours researching to get the details I need so that the layers of politics, history, and the personal are all there together on the page.

March 14, 2022

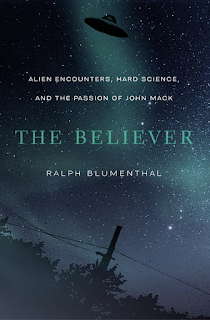

Alien Encounters, Hard Science, and the Passion of John Mack. Ralph Blumenthal writes about his fascinating new book THE BELIEVER

The Passion of John Mack:

A Hero’s Journey Into the Heart of Cosmic Darkness

By Ralph Blumenthal

What was I thinking when a used paperback fell into my hands in Texas in 2004? I can’t honestly remember. As the new Houston bureau chief of The New York Times, I was always looking for story ideas. But I sure wasn’t thinking that here was a book that would upend my world and send me on a voyage of nearly two decades into the deepest mysteries of creation.

The title was intriguing enough: “Passport to the Cosmos: Human Transformation and Alien Encounters.” That’s even before I saw that the author, John E. Mack, was a Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Lawrence of Arabia. What, I wondered, was a distinguished Harvard academician doing writing about extraterrestrials? I was more intrigued after finishing the book, an account of Mack’s unlikely investigation of seemingly normal people with stupefying accounts of interactions with unearthly creatures that (who?) abducted them for apocalyptic warnings of planetary destruction, bizarre pseudo-medical tests, and the harvesting of eggs and sperm for the apparent breeding of a hybrid race.

I had spent my then-40-year Times career writing about very different -- and decidedly earthly -- subjects like crime, cops, crooked politicians, and Nazi war criminals. But here was a story hard to pass up. I resolved to track down this Professor Mack for an interview. I had little idea how prominent he already was, having aired his research in two best-sellers, countless articles, and TV interviews -- and having survived a secret Harvard inquest, or inquisition, to use a term of one of his tormentors.

But then I picked up The Times a few days later in September 2004 to find Mack dead. He had been in the U.K. for a T.E. Lawrence retrospective and, looking the wrong way down a London street, as Yanks are wont to do, been run down by an inebriated driver.

That was hardly the end of my interest, but rather a new impetus. Now the story had an ending, however grim. I found Mack’s half-sister, Mary Lee, in Massachusetts and requested access to his archives. She and Mack’s wife, Sally, and their three grown sons, Danny, Tony and Kenny, were too understandably grief-stricken to immediately respond. But I stayed in touch with them and eventually they agreed, making available his vast archives, including his private journals, unpublished manuscripts, home movies and family photographs, even taped sessions with his own Indian guru therapist. The only exclusions were privacy-protected interviews with patients and research subjects, although some of these, too, would emerge over time.

And so began my own quest that would consume the next 17-plus years, through publication of my book, “The Believer: Alien Encounters, Hard Science, and the Passion of John Mack” (High Road Books/University of New Mexico Press). The paperback comes out March 15, 2022, a year to the day since publication of the hard cover.

So what did I learn? That Mack had stumbled on a colossal mystery, one that seems as intractable today as when he encountered it in 1990 in a serendipitous visit to another unlikely pioneer, Budd Hopkins, an artist whose sighting of a UFO on Cape Cod had come to obsess him, as it would Mack, with an inexplicable conundrum. Before meeting Hopkins, Mack assumed that anyone recounting an abduction by alien beings had to be mentally ill. But then Hopkins sent Mack off with a bundle of letters from people sharing their unfathomable experiences, and Mack was hooked. He never did answer the ultimate question of what lay behind the abduction riddle but he grew convinced of one thing: somehow, in whatever dimension of reality, something undeniably terrifying had indeed happened to these people.

Mack’s heroic journey into the heart of cosmic darkness (as I came to think of it) was rooted in a maverick stubbornness to follow his own lights, as one of his favorite poets, Antonio Machado, had written: “the path is made by walking.” Mack had grown up with a strong moral compass in a well-to do secular German-Jewish household. His father, Edward, was a professor of English at the City College of New York (at a time when I was an undergrad there -- one of many strange synchronicities I later recognized). Mack’s birth mother, Eleanor Liebman, from a family of transplanted German brewers renowned for their Rheingold beer, had died of appendicitis when Mack was an infant, leaving him with an aching sense of loss that came to haunt his subsequent search for the hidden in the cosmos. Adding to his angst was a new stepmother, Ruth Prince Gimbel, a onetime socialite and strong-willed New Deal economist, the widow of a great-grandson of the founder of the department store chain, who had jumped out of a window during the Great Depression, leaving her with their four-year-old daughter, Mary Lee, who became Mack’s unexpected sibling. (I also later came across some of Ruth’s papers at Baruch College where I was organizing archives -- another synchronicity.)

Mack attended Oberlin and Harvard Medical School, soon joining the Harvard psychiatric faculty where he established ground-breaking mental health services in long-downtrodden Cambridge. He had fixated on Lawrence of Arabia after seeing the Hollywood blockbuster, prompting him to spend a dozen years on a landmark study of the quixotic British adventurer, “A Prince of Our Disorder,” awarded the 1976 Pulitzer Prize for biography. Suddenly the author was a recognized expert on the war-torn Middle East and soon an avid campaigner for peace and protester against atomic weapons. He experimented with LSD and other hallucinogens and, at a 1987 demonstration of Dr. Stanislav Grof’s Holotropic Breathwork at Esalen on the Pacific, excavated new dimensions of his consciousness. He imagined a previous life as a Russian peasant and his mother’s struggle to bring him to life. And it was at another breathwork seminar that he learned of Budd Hopkins and alien abduction.

Mack had quickly assembled his own group of experiencers -- his preferred term of neutrality for those who had encountered God-knows-what -- and soon came to some powerful conclusions. These people weren’t crazy. Something truly terrifying had indeed happened to them. But what? There was, of course, no hard evidence. Yet Mack was intrigued by Budd Hopkins’s letters and the congruence of the countless similar accounts he began hearing from so many different and otherwise normal people, teachers, housewives, engineers, doctors, lawyers, police officers and every other profession. They were notoriously publicity shy, so unlikely to be fabricating outlandish stories for fame or profit. Some were little children, too young to be quoting books or movies. One common denominator was the sighting of a U.F.O., although not every experience involved a spaceship. And everyone seemed genuinely terrorized in ways a trained psychiatrist could recognize.

Mack ended up laying out 13 of his best case studies in a 1994 bestseller, “Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens.” Predictably, it discomfited superiors at Harvard where his unconventional research had been hardly a secret but now, displayed to the world, it was drawing ridicule from influential alumni. A secret committee of inquiry was convened, subjecting Mack to intrusive questions about his beliefs and methods. But in the end, he was exonerated of any wrongdoing and continued his research, foraying into other mystifying byways of the anomalous, from crop circles to survival of consciousness -- life after death. Some said they even encountered Mack’s spirit after he passed.

Mack, I granted, was at times naive and gullible. His heroic quest for the ineffable in the cosmos may well have been rooted in something as profoundly personal as the childhood loss of his mother, a trauma that left him in long search of missing love, to, ultimately, the sad undoing of his marriage. Mack knew all this, of course, and persisted nonetheless, consumed by an intractable mystery we have yet to fathom. But he at least began the path, by walking.

---

February 18, 2022

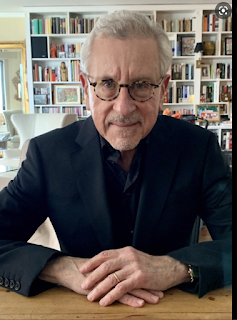

Jonathan Papernick (perfect last name for a writer, right?) talks about I AM MY BELOVEDS, infusing Judiasm in his work, "method-writing." and so much more

A modern couple tests the complicated boundaries of their relationship in Jonathan Papernick's astounding new novel, I am My Beloveds. Jonathan is not only a longtime pal, he's also the author of the brilliant novel The Book of Stone, and the short story collections, The Ascent of Eli Israel, and There is No Other. He's the Senior Writer in Residence at Emerson College in Boston, and the founder of Paper & Ink Editorial. "Papernick's fiction takes no prisoners," Says Hadassah magazine. "And the New York Times praises his "muscular certainty." You'll love his work, too.

When did you know you were a writer?

For as long as I remember I have always wanted to be a writer. I grew up right across the street from a shopping mall and the bookstore there was a magical place for me and I would go there when I had nothing to do and browse through the books. I think the first story I recall that made me want to be a writer was when my second grade teacher Mrs. Spooner read us The Hobbit. I think from that point at like six or seven years old I definitely knew I wanted to be a writer and for years I wanted to write that kind of high fantasy stuff and did a lot of Lord of the Rings kind of fan-fiction with trace pictures from the cartoon movie that came out a million years ago. I just didn't think I had the talent through much of my high school years and even had a high school creative writing teacher tell me she thought I wasn't a very strong writer, but I've always wanted to be a writer and now my fifth book is coming out with my sixth on the way later in the year.

What’s your motivation for infusing Judaism into your work?

I write about Judaism in my work because I write about what I am interested in, and writing about Judaism explains things to me that I couldn't possibly understand through any other process. I grew up kind of ignoring my Jewish heritage even though I did have a bar mitzvah, but after I went to Israel in my early 20s I realized I was part of a really powerful and beautiful tradition. I still don't enjoy going to synagogue and I don't keep kosher, but I engage with Jewish ideas through my fiction that help explain to me how I relate to Judaism. I see the world through a very Jewish lens, so it would be dishonest for me to write through the eyes of a Catholic priest or a Buddhist monk. This is my tradition and this is how I understand it, through my fiction writing.

Do you believe in method-writing, or experiencing what your characters do?

There is a sort of fallacious idea that we are supposed to write what we know, but I believe that it makes more sense to write about what you want to know. I usually come up with a situation, and a character who desires something and figure out what they do to try and get that. So, everything I write comes through my experience even if I'm writing about an octogenarian Holocaust survivor, or a suicide bomber or somebody in a polyamorous relationship. There are bits and pieces of me in all of my characters, but I don’t need to experience what has happened firsthand to write about it. I just imagine my way into each character through an almost meditative state. When I sit down to write, it's like a smarter part of myself steps out of the darkness of my subconscious and whispers the answers in my ear. Of course experience is always valuable; I could not have written my first book, set in Jerusalem if I hadn't lived in Jerusalem. I could not have written my first novel which was set in Brooklyn if I didn't live in Brooklyn, but all of the characters are fictional for the most part and are made up of bits and pieces of me or potential me’s.

Which of your characters would you want to have dinner with most?

I feel like I have already had dinner with all of my characters because when I am writing they live in my head so strongly it is as if they are present. I've written about more than my fair share of psychopaths, crazies and weirdos, so I would certainly have to pass on dining with any of them irl. I think all of the characters in my new novel I Am My Beloveds are most similar to me since none of them are killers or psychopaths and just ordinary confused people trying to figure out love. Now if you were to ask me which dead person I would like to have dinner with, I would throw a massive dinner party with Anthony Bourdain at the head of the table, and Bruce Lee, and probably Jesus because I really want to know what he has to say about all of the things that have been done in his name; Amy Winehouse would be awesome, Hedy Lamar, though I don't know much about her, but she sounds pretty awesome, Winston Churchill, David Ben Gurion, Albert Camus and Lenny Bruce. My living date would be Lana Del Rey. I'd make sure there would be plenty of alcohol and I would livestream the whole thing.

What type of the scene do you find most challenging to write?

I don't believe there is a particular kind of scene that I find most difficult. I am equally comfortable writing ultraviolence as I am writing an intimate sex scene. I'm very comfortable with dialogue as well as lengthy description. Heart to hearts and crazy rants are all the same to me. I think it really comes down to how creative I am feeling at the time. Lately it has become more and more difficult for me to get into that writing headspace where I'm able to channel these characters. So when I can't get there I can't really seem to do anything right, but when I do get there, anything goes.

Do you approach each novel project in the same manner? Is there a formula to your methods?

I think I approach each writing project in the same manner. Fear, panic, and doubt. There are some moments of great confidence and that is when I'm able to convince myself it's okay to write, but I do find it challenging to sit down and write, so when I'm on a roll, I try and keep it going as long as I can possibly do so. Some projects take more research. My first collection of stories relied on lots of things I experienced in Jerusalem, but I also did some supplementary research. In fact I had so much material left over in my mind that my novel the Book of Stone just built upon that material to write about a terrorist plot with Jewish extremists in Brooklyn. I Am My Beloveds took some research, but a lot of it came from my own heart, but certainly listening to Dan Savage's Savage Lovecast was a constant voice in the back of my head.

January 27, 2022

In Kimmery Martin's eerily prescient new novel DOCTORS AND FRIENDS, three doctors (all friends) find themselves facing a contagious virus spreading across the globe. Here, Kimmery talks about her gripping new novel, her work in ERs, the politics of medici

When Ron Block, one of the literary world's guardian angels, AND the podcast host for Friends and Fiction AND the chief honcho for the wonderful Cuyahoga County Public Library tells me that I have to meet an author, that we will love each other--I ALWAYS LISTEN BECAUSE HE IS ALWAYS RIGHT. And yep, yep, he was.

Kimmery Martin is an emergency medicine doctor-turned novelist whose works of medical fiction have been praised by The Harvard Crimson, Southern Living, The Charlotte Observer and The New York Times. Kimmery is hilarious, smart and I also loved her novel DOCTORS AND FRIENDS. So does everyone else, because look at the praise:

"The lives of three doctors—friends since medical school who meet for an annual get together—are thrown upside down when a contagious virus begins to spread across the world in this eerily prescient and timely novel written before the COVID-19 pandemic. Martin’s complex characters are infused with such raw emotion that they nearly jump off the page.”—Newsweek

“Martin’s riveting latest focuses on a group of doctors during a pandemic…Martin fills the hospital scenes with vivid descriptions and moving moments. This fully realized account of a fictional pandemic manages to convey the deeply personal as well as the bigger picture.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“With echoes of Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone, John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza, and Anna Hope’s Expectation, Doctors and Friends is precise in details but sweeping in scope and impact. With an innate understanding of emergency room medicine, the inner workings of government agencies, and the complexities of decades-long friendships, Martin’s novel is compelling to its core.”–Booklist (starred review)

“There is beauty in Martin’s gem of a story that confirms that friendship is a powerful force.”– Library Journal (starred review)

Thank you so much, Kimmery for letting me pepper you with questions! And thank you so much for waiting for me to recuperate from my daredevil headlong fall down a flight of stairs.

I always believe that authors are somehow haunted into writing their books, that they write to answer a question that won’t leave them alone. Is it that way for you?

Yes, to a degree. I’m character oriented: the first thing that occurs to me is the personality of the protagonist. (Which is not a great way to begin a novel, actually, because readers care most about the big central question every novel seeks to answer.) But once I have my main character settled, then figuring out their particular challenge comes next, and I think that does spring from some sort of mental haunting. The head of an author is a truly weird place.

Let’s talk about Doctors and Friends which I loved. And so does everyone else because you have starred reviews from everyone. Reviewers have praised it for being eerily prescient. So I have to ask, when you were writing it, as a doctor yourself, did you always have expectations that a pandemic was waiting to happen?

Sure. We’ve been locked in periodic mortal combat with viral pathogens since the dawn of humankind. It didn’t require a degree in epidemiology to figure it would happen again. I didn’t expect it to happen precisely as I was finishing a novel about it happening, however. The one good thing about the timing, though, was I learned a nifty new word: prescient. It turns out professional book reviewers really like that word. I might get a tattoo of it.

Not only do you write about serious subjects, but you are hilarious about them. Even your bio on your website had me laughing. So I have a weird and hopefully fun question. Do you or did you have different personas as a doctor and as a novelist? How do the two intersect?

I’ve got to congratulate you because no one has ever asked me that exact question before. I do think there is some overlap in the fields of medicine and literature, because in both careers you are dealing with a lot of drama. The difference is that as a doctor you are trying to alleviate suffering and as an author you are deliberately inflicting it. (I should probably clarify that last part: as an author you are trying to inflict suffering upon your characters, not upon your readers. Although you would think it was the opposite if you read my Goodreads reviews.)

As a physician, I’ve been blessed to work in a field where I can offer an immediate impact on the life of other human beings when they’re injured or ill. Emergency medicine is a career overflowing with people at their most vulnerable. We work alongside them, trying to diagnose their sickness, ease their pain, haul them back as they walk the line between life and death. I can’t imagine practicing emergency medicine without humility and a strong sense of compassion.

But to better answer your question: the voice in my novels is pretty similar to my actual voice (i.e. nerdy and a bit snarky.) I tone down my sense of humor at work because a sense of humor during an emergency is prized by no one. Just as the best writers are those who possess keen insight into others, the best doctors are those with empathy as well as technical competence. I don’t know if those qualities are abundant in my writing, but I tried my hardest as an ER doctor to treat everyone with respect and compassion … and I cared very much about what happened to my patients.

You might call yourself a lifelong literary nerd, but I am a lifelong medical nerd. I used to be the one reading JAMA in the waiting rooms while everyone else was looking at People. (Hey, I have a subscription to that one.) And I’ve been told by all my doctors that Emergency Medicine is where the most exciting medicine is. Tell us about that, and about how you moved from there to multi-starred author!

You are obviously way cool, Caroline. And yes: EM is not dull. It comes in handy at parties: when everyone finds out you are an ER doc, they immediately want to know what the weirdest object is you’ve ever extracted from somebody’s nether regions, if you catch my drift. I’m not kidding: I think laypeople see the ER as 10% heart attacks, 10% broken bones, and 80% sex gone wrong. (And with that statement I’ve probably taken your blog in an entirely uncharted direction.)

I became a novelist because I am, first and foremost, a reader. I love words, love stories, love books of all sorts. But I’d never been a writer. When I first had the wild idea to try to write a novel, I was clueless about the process. How to structure scenes, how to craft compelling dialogue, how to maintain suspense—those are all things I learned the hard way, by doing it very, very wrong. Now I teach writing classes on those subjects but the road to basic competency at authoring was long and humbling for me. I attended conferences and read books and received a lot of help from other writers. Which is another thing my two careers have in common: both authors and doctors (especially women) are exceptionally supportive of one another.

What kind of writer are you? Do you map things out or just let them go with the flow?

I’m all flow, unfortunately. I wish I weren’t: it’s an inefficient way to write. I understand the principles of plotting but so far I haven’t been able to achieve them up front. So I try to apply those techniques to my revision process.

What’s obsessing you now and why?

Ohhhhh. Ugh. Well, several things: I think a lot about the bizarre turn our country has taken with regard to the politicization of medicine. Deep divisions, where we cannot even agree on the most fundamental aspects of science, or of reality, for that matter. The devaluation of expertise in favor of whatever suits your bias. Demagoguery. Authoritarianism.

But those things are happening more on a macro-level. When you talk with ordinary people, they are often far more likely to listen to one another and less likely to label each other as the enemy. All this division we are experiencing right now is history repeating itself and I believe there are ways out of it.

On a different note, I am fascinated by the intersection of quantum physics and the biotechnologies of the future—and what the applications and implications might be. I love reading dumbed-down theoretical physics books.

What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

Usually when people realize I wrote a pandemic novel before Covid, some degree of apprehension flits across their face. This always precedes the same question: what am I working on now? So … I’m not going to answer that one because I don’t want to alarm everyone. Let’s just say what I am writing about now is less likely to occur than the events of Doctors and Friends.

January 8, 2022

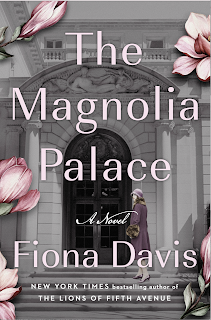

Fiona Davis talks about The Magnolia Palace, dual timelines, writing strong female characters, writing during lockdown, and so much more!

Note the sublime photo above, of Audrey Munson. the first supermodel who was named "Miss Manhattan." The perfect icon for a blog about Fiona!

I adore Fiona Davis. Not just her books, either. I'm not sure when we met, but I keep happily running into her at books events (or I did, pre-pandemic, and every time I do, I get a glow. She is the New York Times bestselling author of six historical fiction novels set in iconic New York City buildings, including The Dollhouse, The Address, and The Lions of Fifth Avenue, which was a Good Morning America book club pick. Her novels have been chosen as “One Book, One Community” reads and her articles have appeared in publications like The Wall Street Journal and O the Oprah magazine. She first came to New York City as an actress, but fell in love with writing, and we are all so happy she did.

Her newest masterwork, The Magnolia Palace is about lies, betrayals and even murder in the gilded age mansion. It's got starred raves from Kirkus, Library Journal and from Publisher's weekly, and a slew of raves from the likes of Christina Baker Kline and Lisa Wingate. Welcome Fiona! I just wish this was in person!

I always believe that writers are somehow obsessed into writing the books they write. What was haunting you that created this wonderful book?

I’ve always loved wandering around old buildings and wondering about the people who lived there over the years, so writing about iconic landmarks really fuels my obsession. The Frick Collection was built in 1914 as a residence, and then turned into a museum in the thirties. As a museum, it feels like it’s been frozen in time, with splendid furnishings everywhere and art by masters like Rembrandt, Turner, and Vermeer hanging on every wall. When you walk in, it’s as if the Frick family is out at a dinner party and will be back at any moment.

I love that you set your novels in these fabulous New York Buildings! I always feel that buildings have their own personalities, almost something you can feel when you go inside. Do you walk into these great buildings and just inhale the atmosphere and then ideas perk? And can you tell us what building is next?

The building definitely becomes like another character in the story, with its history and layout impacting the plot. During my behind-the-scenes tour of the Frick, I discovered there’s a circa 1914 bowling alley in the basement – which still works – and of course had to include that as a scene location. As I wandered the rooms I definitely began to imagine ideas for scenes and characters. For example, what was it like for a member of the household staff who lived on the top floor, with that splendid view of Central Park? As for the next book, I have a short story being published this summer that’s set at Carnegie Hall, and then the next novel is set at Radio City Music Hall, from the point of view of a Rockette in the 1950s. There are so many possibilities in New York City!

There’s so much wonderful material in this book, from the Spanish Flu to the Frick Mansion/Museum. (I love the Frick and imagine you went to visit and visit and visit again.) What was your research like?

Because the world went into lockdown a couple of months into my research, I wasn’t able to get back inside after my initial tour – and in fact now it’s closed for renovations (although the works of art are brilliantly exhibited at the Frick Madison nearby). Luckily, at the Frick’s website (frick.org), there’s a floor plan with a 360-degree view of all of the public rooms. So I virtually visited multiple times a day as I was writing the drafts. Research for this book involved going through the Frick archives, which had fun surprises like dinner party menus from 1915, or payroll records of the staff, as well as interviewing experts in the art world.

I loved your female characters, as I always do, Veronica Weber and Lillian Carter. So here is a writerly question. How did you go about developing those women? And what parts of you are in your characters? And what parts of them do you wish you had?

Veronica and Lillian are both models in different time periods – Lillian in the 1910s and Veronica in the 1960s, so it was really fun to figure out how that particular career had changed over time – and also the ways in which it hadn’t. I wish I was more of a free-spirit like Lillian, who is willing to take huge risks and throw herself into life. I’m afraid that’s just not my style. Veronica is probably a little more like me: slightly overwhelmed in a crowd and happy to watch the action from the sidelines.

And another writerly question. Using a dual timeline nearly killed me! Any tips, because you did it beautifully.

Dual timelines can be an absolute beast, no question. I figure out the plot and outline it fairly thoroughly before I sit down to write that first draft. There’s so much to keep track of, especially with an element of mystery and clues that need to be dropped at the exact right time. Once that outline is firm, I tend to write the older timeline first, and then the newer one. I find that’s easier than bouncing back and forth, which will ultimately be the way the reader views it.

What’s obsessing you now and why? What question didn’t I ask that I should have?

These days I’m obsessed with the novel The Ballerinas, by Rachel Kapelke-Dale, which is set in Paris at the ballet, and is beautifully written and a great mystery as well. And I think you covered all the bases! Thank you for this amazing opportunity, and I can’t wait to see you in person one of these days and give you a (gentle) hug.

November 7, 2021

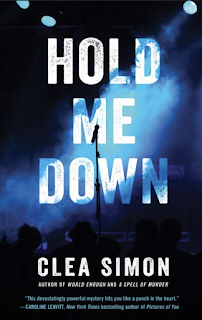

Clea Simon talks about Rock and Roll, the 1980s, memory, and her raved-about new novel HOLD ME DOWN

I am so thrilled to Host Clea Simon my blog! Yep, I blurbed her new novel, HOLD ME DOWN, because it is so incendiary, so thrilling, so important, too. And I'm honored to have her here. Thank you, Clea!

Hello! Thanks so much for hosting me, Caroline, and for helping me to celebrate my new psychological suspense, Hold Me Down.

Gal Raver was a rock star. But that was 20 years ago and as HOLD ME DOWN opens she is back in Boston playing a big stage for the first time in years. The occasion is a memorial concert for her late drummer and best friend Aimee, who cofounded the band with her. But as she’s playing she sees – or think she sees – a face from the past, which unsettles her. The next day she hears that that person was murdered behind the venue and Amy’s widower Walter arrested. When Walter chooses not to fight the charges, Gal is compelled to get involved – not only to save her friend but to understand why, for a moment there, she thought “it should’ve been me,” an investigation that leads her back into her own wild, rock star days.

Why did you set this book in the rock world?

For starters, it’s a world you and I both know well! Like Simon at the start of your wonderful With or Without You, Gal begins her journey living in clubland – as did I, once upon a time. Back when I was in my twenties, I not only worked as a rock critic, I lived for the scene. It was my “third place,” neither home nor work. Where I spent my free time, and where I forged so many relationships.

I guess, in a way, those relationships are key. Because it’s such a self-contained world, the relationships that develop in it are great for fiction: the same characters thrown together constantly, with generous helpings of alcohol and other substances, are bound to interact in interesting ways. For me as a mystery writer, the club world functions like an English village would in a classic Agatha Christie novel – whatever happens, whatever crimes and whatever motives – are going to spring organically from a contained cast of characters.

It also interested me, that for all that rock is obsessed with youth with the now, it also constantly seeks to memorialize itself. When we meet Gal, for example, she’s playing a benefit – songs that she wrote twenty-odd years before. And, of course, once something is written or recorded it becomes a time capsule – a reflection of what was happening then. With crime fiction that also allows you to plant clues or exposition

What research did you do?

I tried to evoke the physical memories of those days: Listening to a lot of older garage-punk bands. Picking up my electric bass for the first time in ages. I’d forgotten how heavy it is and how you stand when it’s strapped onto your shoulder.

Other than that, I talked to a bunch of people who were on the scene at the time, many of whom were willing to share some very personal memories. These conversations all fed into my memories – and into who Gal was becoming in my mind. For example, when a buddy who used to sing with a band mentioned how far back into a club she could see from onstage, I thought, “I can use that.” And then, when I have Gal noting that, I realized, well, yes, Gal can see all the way to the dark corners of the club. But is she really seeing hijinks back there, or is something else going on?

So Gal is an unreliable narrator?

Not in the sense of, say, Gone Girl, where the narrator sets out to deceive you. Hold Me Down is written in close third person: Gal is telling us what she believes she knows. But what that is is unreliable as it is for all of us. Our perception of what is happening is always subjective. Throw in memory, and it becomes even less objective, as nostalgia, denial, and regret all tend to shift our understanding of what is real.

This uncertainty is really at the center of Hold Me Down. At its core are really two mysteries: Who committed the murder (and why isn’t Gal’s friend Walter defending himself), but also what happened to Gal to bring her to this point?

Hold Me Down flips back and forth in time, why did you decide to do that?

Really three times. We first meet Gal in the present day, when she’s jaded, sober, but kind of stuck in a holding pattern. In flashbacks, we see Gal at her rock star peak, when she was kind of crazy but unstoppable. But we also get peeks of the young Gal who first started the band with Aimee, nearly paralyzed with stage fright, dying to break though.

I’m realizing that one of my constant themes seems to be memory – not only nostalgia and regret but the way we the past sets us on specific paths

Not to give too much away, but you also deal with trauma – sexual assault and PTSD

Yes, Gal’s a survivor, as am I. As many of us are – but even though we survive, we’re shaped by what we’ve experienced. It’s like we’ve been pushed slightly askew by what hit us. Our lenses on the world are maybe a bit warped. So again, Gal sees things that are maybe not quite as they should be.

Gal’s songs reflect a lot of what she went through, don’t they?

In a way they serve as touchstones for who she is at any given time. I really enjoyed exploring how she interacts with her own work. For example, when she’s young and anxious, she’s very careful about crafting a bridge to one of her tunes. Later, at her rock star wildest, she dismisses that same bridge as overly fussy and skips over it in concert. What else does she want to skip over?

But these songs exist outside of Gal, too, and the reader gets to see how everyone reacts to them, from the suits from the record label to the fans. And, perhaps most important, Gal’s bandmates, who may hear something different than Gal does – or perhaps than she intended. These songs take on a life of their own, and they serve to reflect back not only who Gal is at any given time, but how she is received in the world.

How would you describe Gal, as she is when we meet her?

She’s fiercely loyal. She can’t leave Walter even though he doesn’t want to defend himself. That’s partly because of her love for Aimee, which she’s transferred to Aimee’s daughter Camille and also to Walter. But she is also coming to terms with the damage she’s done to those she loved.

I love writing about process – what it feels like to channel something and then to craft it, whether that’s a song or a story. But it requires really making yourself vulnerable. You and I have talked about this, how as writers, we have to “go for the heat” and write about whatever feels most immediate or real. You’ve always encouraged me to be brave and do this, and I’m so grateful! I think it’s one of the reasons you’re such a great friend!

A former journalist, Clea Simon is the Boston Globe-bestselling author of three nonfiction books and 29 mysteries. including the new psychological suspense HOLD ME DOWN. While most of these (like A Cat on the Case) are cat “cozies” or amateur sleuth, she also writes darker crime fiction, like the rock and roll mystery World Enough, named a “must read” by the Massachusetts Book Awards. Her new psychological suspense Hold Me Down (Polis Books) returns to the music world, with themes of PTSD and recovery, as well as love in all its forms. She can be reached at www.cleasimon.com, on Twitter @Clea_Simon and on Instagram @cleasimon_author

October 30, 2021

Larry Baker talks about WYMAN AND THE FLORIDA KNIGHTS, Florida, mortality, writing, the looming presence of Trump, and so much more.

Larry Baker is the author of From a Distance, The Flamingo Rising, The Education of Nancy Adams, Love and Other Delusions, A Good Man, and his latest, most wonderful novel WYMAN AND THE FLORIDA KNIGHTS. He's also become a treasured friend and I am delighted to host him here! Thank you, Larry!

I always believe that writers are haunted into writing books. What was haunting you?

Haunted? Oh, other than a compounding fear of death and obscurity. I am 74. I have published seven novels. I think my best one is still trapped inside me, but I have less and less time, less and less energy. Cliched metaphor warning: A lack of sand in the hourglass haunts me.

For WYMAN, I wanted to do something I have never done, attempt historical fiction. Not focusing on an individual, but a family over centuries. Having become a grandfather, myself, I am more aware of my own past, and I see my future in my grandsons, my family story continuing with them. I am optimistic about their future, but as I was writing WYMAN, I began to see how a family often has to overcome its past, its origins. In literary terms, the Faulknerian sins of the fathers. I'm a lapsed Baptist, a current Catholic agnostic, but I have never shed my Christian sense of guilt. Go back to Cain and bel, and toss in an artist's Faustian Bargain, and you'll understand what was haunting me.

What's your usual writing life like, and has it changed during the pandemic?

Sadly, I write less and less nowadays. That began when I finished the first draft of WYMAN a year ago. Old age, some family health problems, life itself has changed how I write. If the Pandemic had occurred a few years ago, with the enforced isolation, I suspect that I would have written one or two more novels. I no longer have the five hours a day of uninterrupted isolation that made me productive in the past.

WYMAN and the Florida Knights is actually dealing with really contemporary issues. Can you talk about that please?

The story begins in 1866 with the arrival in Florida of the Northern Evangelical Thomas Knight and it ends on Election Day 2016 before the votes are finalized. Trump is a looming figure in the background in 2016 but this story ends before the polls are closed, so the reader will have to imagine how his election will change the characters' lives. The Knight family came as Northern Republicans but their kind of Republicanism has devolved by 2016 and they are about to be usurped by darker forces. Thus, WYMAN is about how Florida is the avatar of American fragmentation. That sense of political fragmentation has parallel stories of alienation in the private lives of all the characters. Fathers and sons. Husbands and Wives. Artists and art. All unable to connect. But the story has a hopeful side. The old Knights are gone, but a new generation is rising.

Throughout my story, the characters are all battling to determine who tells their story. The central character is Sandra Knight, the owner and editor of the small-town newspaper. One of my favorite chapters in the book is when she goes to a T4ump rally in Orlando. Plus, the role of journalism (my first college major a million years ago) has always intrigued me. Sandra has to deal with every economic and social force that is killing newspapers all over America. Of all the characters in WYMAN, she works the hardest to keep her town from vanishing.

I always want to know, do you feel that a new book grows out of an old one, or must you wrestle with something completely new?

Well, since most of my novels have been under-whelming sellers, I can safely steal from myself and most new readers will never know. So, if I were an objective critic of Larry Baker, I would say that he is perennially writing about a few themes that recur over and over in his work. Emotional obsessions top that list. Misguided love, a quest for the ideal mate, sins and moral lapses done in the pursuit of some idealized "other." My first novel, FLAMINGO RISING, had a character named Alice, inspired by a real person. But, with that character written, that inspiration became irrelevant.

My novel, A GOOD MAN, also had an Alice who was hiding from her past. The second Alice was not inspired by the real person who inspired the first. WYMAN also has a character named Alice.

Other recurring themes? A quest for faith. And the universal theme of fiction--identity. How well does a writer know his characters, how well do they know themselves? With WYMAN, I made ample use of a trope I first explored in A GOOD MAN, how a character hides themselves in a name. I named a character Harry after a boy named Harry in a Flannery O'Connor story and after a radio DJ in a Harry Chapin song. Their stories, written by other writers, became the background for my own Harry.

Me, I have always hated my own name, Larry Baker. I look into a mirror, I do not see a Larry Baker.

I love that you write about Florida, especially now with all that's happening there. Talk about that, please.

I lived in Florida for three years, enough time to accumulate a ton of material for fiction. It's a unique state. In the early 1800s, it was the least American of all the other states. part of that was its Spanish background, but the single most important distinction was its natural environment. Today, science and capitalism have destroyed that original environment. Today, Florida might be the most American state, a hot mess, the worst of what America is becoming.

What's obsessing you now and why?

Did I mention my sense of dwindling mortality? In literary terms, I might have one final project. I self-published a political novel in 2005, ATHENS/AMERICA, but I was never happy with it. It was too autobiographical, and thus too off-putting for most readers. Surprise, surprise, I am not always a sympathetic character. But the core of that story, how do fathers deal with the loss of a child, was still compelling to me. I needed another voice in the story, an observer of the two fathers in my original version.

As I looked at ATHENS again, I imagined a new character, arriving. Adding him let me create a backstory for him. I'm going to self-publish my revised novel in 2022. New title? THREE MEN AND A DEER.

What question didn't I ask that I should have?

I dunno, maybe, "Have you dusted off your mantel and made a space for your future Pulitzer?" Or, "Your wife must be incredible patient and forgiving. Why did she marry you?" But here's a question that I like to ask other writers: "Is it possible to write an honest memoir?" People tell me all the time that I should write a memoir, but I have a simple answer: Never. I've been writing fiction for almost sixty years (not to be confused with publishing fiction.) Any processing of my life has been done through that, turning facts into fiction.

August 30, 2021

Cai Emmons talks about Sinking Islands, weather, living with ALS, writing, and so much more

I met and befriended Cai the way I do almost every new friend: a book comes in the mail and I love it so much, I have to know the author! In Cai's case that was Weather Woman, followed by Sinking Islands. I'm thrilled to have Cai here, and I thank her for her patience with me for taking so, so long to get this up.

Cai Emmons is the author of the novels His Mother’s Son (Harcourt), The Stylist (HarperCollins), and Weather Woman (Red Hen Press). A sequel to Weather Woman, is called Sinking Islands. Her story collection Vanishing, winner of the 2018 Leapfrog Fiction Contest came out in March 2020. His Mother’s Son received starred reviews from Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly, was a Booksense and Literary Guild selection, was translated into French and German, was reviewed by O Magazine and The Economist, and won an Oregon Book Award (the Ken Kesey Award) for fiction. About The Stylist, one of the earliest novels featuring a transgender character, Booklist said: “With family relations as twisted as a French braid and language as vivid as a platinum dye job, Emmons’ potent novel features magnetic characters and complex and compelling secrets.” Weather Woman, Emmons’s most recent novel, about a meteorologist who discovers she has the power to change the weather, has been featured in such places as LitHub, The Rumpus, Book Riot, Montana Public Radio, Aspen Public Radio, The CCNY Grad Center, among others (see more coverage under “News”). The novel won a Nautilus Book Award and has been shortlisted for the Eric Hoffer Grand Prize.

What was haunting you into writing your latest book?

I love that you speak about this idea of being haunted into writing a book. I’ve never heard anyone speak about writing this way, but that’s exactly how it operates for me. Something begins poking at me such that I can’t stop thinking about it. The thinking becomes a bit obsessive. Questions begin to form and maybe a what-if develops, and pretty soon a novel is taking shape. In terms of Sinking Islands, I was haunted by the idea that people might read Weather Woman and think that I was putting forth the idea that a single person with superpowers might be the solution to our climate crisis. I don’t believe that at all. So I wanted to think about human beings collaborating and teaching each other. Having spent my entire adult life teaching in some form or other, and having benefitted so much from my own teachers, I wanted to write about that. Teaching is such a powerful tool. I think we all have a bit of the teacher in us. Good parenting is really all about teaching. There are so many doom-and-gloom dystopian books out there about our climate crisis; I like to think that I’ve written one of the few climate books that offers a modicum of hope—or at least it doesn’t wallow in despair!

Do you feel like your writing grown with each book?

This is another superb question. I always, just after I’ve finished a book, feel that it is the best thing I’ve ever written, but of course that feeling fades quickly and I begin to ask, “Is this really any good?” It is impossible to answer that myself. My agent says she thinks my most recent novel, Unleashed (out from Dutton in 2022) is the best thing I’ve ever written, and I tend to agree with her. But I also feel as if I can never really be the judge of my own work. I can only weigh in on how the process has changed for me over the years.

When I step back and think about each book I’ve written I think that I’ve become more ambitious. When I began writing novels I only dared write from one character’s perspective. Then I began incorporating a number of characters’ perspectives in the same novel. Then I began to stretch my imagination to write about things that are not entirely “real” though they are metaphorically and psychologically real. And most recently I wrote a first-person novel which I have never done before. So I think there has been some growth in terms of what I’ve dared to take on. And there is another kind of growth too—I’m sure you’ve experienced this—which is that you trust the process more and even when you’re stuck you know you can find a way through to the end. Along with that comes an ease with sentence-making and knowing what material is superfluous and can be cut. There is greater facility with manipulating what you have written so that seems like a kind of growth.

I think my biggest fear is that I might begin repeating myself in subsequent novels. In a way I think we’re always writing around the same themes again and again, packaged somewhat differently. But I still feel, despite that fear, amazingly driven to keep writing, to keep exploring what it means to be human.

What’s your writing life like now?

Three years ago I gave up my teaching job in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Oregon. At the time I had two books scheduled for publication, and I didn’t see how I was going to be able to publicize them and keep writing while also teaching. I was a bit frightened to no longer have the cushion of academia, but my husband has a good job that could support us both. I am so glad I decided to prioritize my writing when I did. I had no idea then that I would be diagnosed with ALS (I was diagnosed in February of this year), but something was telling me back then that it was time to go for broke and pay exclusive attention to my own work. I feel a great urgency to write every story that is still in me while I can. So far ALS has stolen my ability to speak, but I am so grateful that I am still able to move around and write and type. The 2020 pandemic year was extremely productive for me, and I now have two books that are scheduled to come out in 2022, and I’m working on a new novel that I hope to complete sometime early next year. Fingers crossed.

My writing days are still much as they have always been, writing first thing in the morning (longhand, with coffee, propped up in bed), and staying there for several hours until I am called upon to participate in the larger world. My afternoons are occupied with typing up what I’ve written or doing the “business” of being a writer. I guess my biggest challenge of late has been figuring out how to publicize my books without being able to speak. I have a high-tech computer that speaks what I type, which is extremely useful, but it necessitates slowing down, for me and for whoever I’m talking to. In social situations I am trying to adjust to being a listener instead of the talker I’ve always been!

What was it like writing a sequel?

Since I never intended to write a sequel to Weather Woman I was figuring things out as I went along. I knew that in Sinking Islands I had to remain true to what I’d set up in Weather Woman and build on that. I couldn’t change backstory events, or names, or rules I’d set up about how Bronwyn employs her power, etc. I was particularly brought up short when one character in Weather Woman, Earl, who I wanted to include in Sinking Islands was off-limits because he was already dead. I considered, very briefly, bringing him back to life, but that would have been violating the world I’d set up. So I ended up having another character, Patty, talk to Earl as if he was still alive. I also debated with myself about whether it would be okay to have Bronwyn have lost a pinkie to frostbite in Siberia, even though I had not mentioned that in Weather Woman (I decided that would be okay since it could have happened after the book ended). I spent a lot of time searching through the pages of Weather Woman for specific details I’d already laid down. It was kind of like doing continuity for a film—I didn’t want readers to discover inconsistencies. So far, no one has, but it’s not beyond the realm of possibility!

What question haven’t I asked that I should have?

I am always intrigued by the question of why people write in the first place, and that question has been more on my mind of late since I know that I will be dead in the next few years. Why do I still want to spend my remaining time writing instead of traveling or doing any of the other things human beings find rewarding? I think part of the answer to that is that when I am writing I am in some kind of flow state and at my happiest. Also, since talking has become so hard there is a great deal I don’t say aloud, so writing has become an even more essential vehicle for expression. And over the years writing has become a habit that isn’t easily broken—it is my way of processing the world around me. But there is that other ineffable thing that keeps me—and other writers—writing. Some pressing desire to document what it feels like to be a particular human being, living in a particular place at a particular time in history. I don’t feel as if my experience is particularly important on its own, but I feel as if I’m part of a chorus of writers all saying, this, and this, and this, and it adds up to an amazing cantata of voices, all of which are neces

July 28, 2021

Portrait of a prolific seventeen-year-old author! Max Rudin talks about writing sci-fi, physics, what inspires him and more!

What's more exciting than discovering new writing talent? Especially when it is from a teenager? I've hosted young people here before (We have a ten-year-old in our family who already has written a novel, and our son Max wrote a novel "Movies of Doom" when he was eight. We gave him the full author treatment, getting blurbs from writer friends, writing a book club set of questions , getting an author photo, too.) So when writer/producer/comedienne /friend Bari Alyse Rudin told me about her talented 17-year-old son, who had already written many books available for purchase, I asked to see a few pages. To my astonishment, they were truly great! Professional! Sophisticated, too. So I wanted to host him on my blog to support him.

Thank you so much, Bari, and huge thanks to Max!

I'm astonished that you are so good a writer at such a young age. When did you first start writing?

Besides assignments for school, I first started writing when I was in fifth grade. In fifth and sixth grade, my friend Sebastian and I came up with many ideas for books that we wanted to write. Over the phone, we’d work together on the start of different stories, never ending up finishing them. However, working on those stories was incredibly fun, and I realized that I loved storytelling. Also, I’ve always had a tendency to daydream and think through different scenarios in my head. Combined with my interest in astronomy, physics, and other sciences, this led to questions about how humans might live in space in the future. By the time I was a high school freshman, I was determined to start and finish a book on my own. That book ended up as my first, A Truly Dead Rock.

Where do you find inspiration? What else do you love besides writing? What books inspire you?

The inspiration for my books started with natural wonders, the different landscapes that exist in space and how they might look. How does a sunset look on the Moon or Venus? Then, I began to think about manmade wonders. How would the sky of a domed city or a large space station look? From these images of beauty, I wrote about the people that would get to see them in the distant future and what sorts of conflicts they might face in their lives.

Besides writing, I enjoy making educational YouTube videos and podcasts. In doing so, I research topics that interest me in science or history and explain them in an intuitive way. This is very fun for me, because I get to teach and because I get to learn. Whenever there’s something I wonder about, I want to research it so that I can teach others about it through my videos or through my writing.

My favorite sci-fi books are Red Mars, Green Mars, and Blue Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson, which were a great inspiration for me. These books outline a detailed history of an inhabited Mars for hundreds of years in the future. They are very long books and include vivid descriptions of the different landscapes at different times in Martian history. These beautiful scenes inspired me to bring other uninhabited parts of the universe to life. I also very much enjoyed Jurassic Park and The Lost World by Michael Crichton. I watched the Jurassic Park movies when I was ten and couldn’t stop watching them over and over. They drew me into sci-fi, and when I found out that there were books behind them, I immediately decided to read them. Crichton’s explanations of complex topics in science and math always made sense, and I enjoyed the logical flow. Understanding the science behind the science fiction enhanced the experience of reading.

You are incredibly prolific! I want to know your secret!