Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 78

June 12, 2015

Signing and Speaking-June 13 & 14-Tidewater, Virginia

I’ll be in the heart of American history country this weekend for two events. Come out and celebrate Flag Day, the U.S. Army’s Birthday … and get ready for Father’s Day (June 21-Hint, Hint!!!)

Saturday June 13 William & Mary Bookstore (Barnes & Noble) in Williamsburg, VA 4-6 PM

Sunday June 14 Tidewater Community College Bookstore in Norfolk, VA. 2-3:30 PM

Please stop in and say hello if you are in the neighborhood!

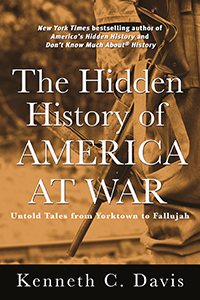

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About the Lovings

The Loving Story Photo by Gray Villet (Source: HBO)

As we await a new set of rulings on marriage equality from the Supreme Court, I am reposting this essay from 2013.

As the nation awaits the Supreme Court’s ruling in two cases related to marriage equality, it is worth revisiting the facts in the case of Loving v Virginia –decided by the Supreme Court on June 12, 1967. The case involved the law in Virginia, and other states, which prohibited interracial marriage, or “miscegenation.”

Loving v. Virginia changed that. And America.

Richard Loving, a white man, married Mildred, a 18-year-old woman of African-American and Native American descent, in Washington, D.C. When they returned to their native Virginia, they were arrested in the middle of the night and the Lovings were forced to leave Virginia. A few years later, young Mildred asked Robert F. Kennedy, the new Attorney General, for help. He suggested the American Civil Liberties Union and she wrote to them. Two young lawyers decided to take the case. They brought suit which eventually found its way to the Supreme Court

The Court ruled that anti-miscegenation laws, such as those in Virginia, violated the “Due Process Clause” (“No person shall be … deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law….” ) and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (“nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law …”). In the unanimous majority opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote:

“Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival.”

The Loving case is clearly part of the arguments that were made before the Supreme Court in a pair of cases in March 2013. (Since those arguments same sex marriage has been approved in Delaware and Minnesota, making same sex marriage legal in 12 states and the District of Columbia.)

Change in American history is often slow. And it usually comes from the bottom up –not the top down. Whether it was abolition, civil rights, or even independence itself, when it comes to most of the great social upheavals of our past, the politicians and “leaders” have generally had to be dragged kicking and screaming in the direction of change. It may be glacially slow, but it will happen, in part because there is a generational change that will someday make the existing same sex marriage prohibitions on the books seem as antiquated –and despicable—as the now-unconstitutional bans on interracial marriage.

Before her death in 2008, Mildred Loving, the woman of African-American and Native American descent who brought the suit against Virginia, issued a statement on the 40th anniversary of the decision. She wrote:

“Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don’t think of Richard and our love, our right to marry, and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the ‘wrong kind of person’ for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people’s religious beliefs over others. I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.”

I can’t say it any better than that.

The January/February 2012 issue of Humanities magazine featured the Lovings as did a recent HBO documentary, The Loving Story.

There is a more complete discussion of the history of the Lovings, their case and its connection to the same sex marriage debate in the new, revised edition of Don’t Know Much About History: Anniversary Edition.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 8, 2015

Who Said It (6/8/15)

View from the West Berlin side of graffiti art on the wall in 1986. The wall’s “death strip”, on the east side of the wall, here follows the curve of the Luisenstadt Canal (filled in 1932). Source : Wikipedia

“The wall cannot withstand freedom.”

Ronald Reagan, “Speech at Brandenburg Gate” (June 12, 1987)

As I looked out a moment ago from the Reichstag, that embodiment of German unity, I noticed words crudely spray-painted upon the wall, perhaps by a young Berliner, “This wall will fall. Beliefs become reality.” Yes, across Europe, this wall will fall. For it cannot withstand faith; it cannot withstand truth. The wall cannot withstand freedom.

This speech is perhaps best known for the phrase:

Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Video of the “Berlin Wall Speech”

Source: The American Presidency Project (americanpresidency.org), established in 1999 as a collaboration between John T. Woolley & Gerhard Peters at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Read more about the Fall of Berlin in 1945, the Marshall Plan and the Cold War in The Hidden History of America At War

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books Random House Audio)

May 26, 2015

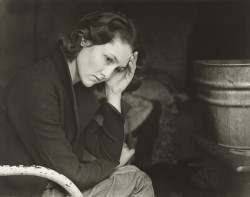

Don’t Know Much About® Dorothea Lange

Daughter of Migrant Tennessee Coal Miner Living in American River Camp near Sacramento, California

(1936) by Dorothea Lange Credit: Gift of the Farm Security AdministrationMoMA Number:313.1938 Source: Museum of Modern Art

Dorothea Lange was born on May 26, 1895, in Hoboken,NJ.

Best known for her photographs of Depression-era America, she also recorded the the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

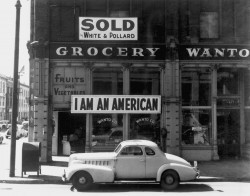

Photo by Dorothea Lange of Japanese-American grocery store on the day after Pearl Harbor Source: Library of Congress

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan, there was a wave of fear and hysteria aimed at Japanese and people of Japanese descent living in America, including American citizens, mostly on the West Coast. In February 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which declared certain areas to be “exclusion zones” from which the military could remove anyone for security reasons. It provided the legal groundwork for the eventual relocation of approximately 120,000 people to a variety of detention centers around the country, the largest forced relocation in American history. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens. (Smaller numbers of Americans of German and Italian descent were also detained.)

Photo Source: National Archives

The attitude of many Americans at the time was expressed in a Los Angeles Times editorial of the period:

“A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched… So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere… notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American…” (Source: Impounded, p. 53)

The exclusion order was rescinded in 1945 and internees were allowed to leave, although many had lost their homes, businesses and property during their confinement. However, the last camp did not close until 1946.

In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate the internment and, in 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which provided for a reparation of $20,000 to surviving detainees.

One of those detainees was Albert Kurihara who told the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981:

“I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget.” (from Impounded, Norton)

Photographer Dorothea Lange also photographed the internment camps and her censored images were published in 2006 in the book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (WW Norton, 2006).

The National Parks Service offers a Teaching With Historic Places lesson plan based on the camps some of which are now part of the National Parks System including Minidoka in Idaho and the Manzanar camp in California.

The Library of Congress offers an extensive collection of Lange photographs.

Who Said It? (May 26, 2015)

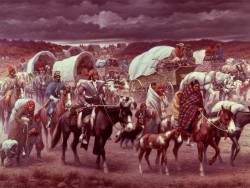

This picture, The Trail of Tears, was painted by Robert Lindneux in 1942. It commemorates the suffering of the Cherokee people under forced removal. If any depictions of the “Trail of Tears” were created at the time of the march, they have not survived.

Image Credit: The Granger Collection, New York (Source PBS Online)

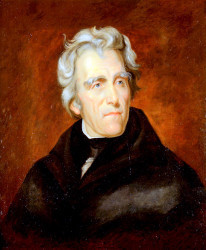

Andrew Jackson “Second Annual Message to Congress” (December 16, 1830)

Andrew Jackson (1825) by Thomas Sully (Source: US Senate)

The benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly 30 years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation….

Toward the aborigines of the country no one can indulge a more friendly feeling than myself, or would go further in attempting to reclaim them from their wandering habits and make them a happy, prosperous people. I have endeavored to impress upon them my own solemn convictions of the duties and powers of the General Government in relation to the State authorities. For the justice of the laws passed by the States within the scope of their reserved powers they are not responsible to this Government. As individuals we may entertain and express our opinions of their acts, but as a Government we have as little right to control them as we have to prescribe laws for other nations….

The present policy of the Government is but a continuation of the same progressive change by a milder process. The tribes which occupied the countries now constituting the Eastern States were annihilated or have melted away to make room for the whites. The waves of population and civilization are rolling to the westward, and we now propose to acquire the countries occupied by the red men of the South and West by a fair exchange, and, at the expense of the United States, to send them to a land where their existence may be prolonged and perhaps made perpetual.

Doubtless it will be painful to leave the graves of their fathers; but what do they more than our ancestors did or than our children are now doing? ….

Complete Text and Source: Andrew Jackson: “Second Annual Message,” December 6, 1830. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830. It gave the president authority to grant unsettled lands west of the Mississippi in exchange for Indian lands within existing state borders.

“A few tribes went peacefully, but many resisted the relocation policy. During the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839, the Cherokees were forcibly moved west by the United States government. Approximately 4,000 Cherokees died on this forced march, which became known as the ‘Trail of Tears.'”

Source: Library of Congress, Indian Removal Act “Primary Documents in American History”

May 24, 2015

Starred PW Review of “The Hidden History of America At War”

The first critical review of my book, The Hidden History of America At War: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah appeared in a “Starred Review” in Publishers Weekly.

“His searing analyses and ability to see the forest as well as the trees make for an absorbing and infuriating read as he highlights the strategic missteps, bad decisions, needless loss of life, horrific war crimes, and political hubris that often accompany war.”

Please read the full review here

May 22, 2015

The Divisive History of Memorial Day

It is a well-established fact that Americans can argue over anything. And we do. Mays or Mantle. A Caddy or a Lincoln. And, of course, abolition, abortion, and guns.

But a debate over Memorial Day –and more specifically where and how it began? America’s most solemn holiday should be free of rancor. But it isn’t and never has been.

Born out of the Civil War’s catastrophic death toll as “Decoration Day,” Memorial Day is a day for honoring our nation’s war dead.

Waterloo, New York claimed that the holiday originated there with a parade and decoration of the graves of fallen soldiers in 1866. When LBJ signed a proclamation there in 1966 that seemed to cement Waterloo’s claim.

But according to the Veterans Administration, at least 25 places now stake a claim to the birth of Memorial Day. Among the pack are Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, which says it was first in 1864.( “Many Claim to Be Memorial Day Birthplace” )

And according to historian David Blight, Charleston, South Carolina can point to a parade of emancipated children in May 1865 who decorated the graves of fallen Union soldiers whose remains were moved from a racetrack to a proper cemetery.

This “We–were-first” sentiment is weighted by emotion. Few towns, north or south were untouched by death in a conflict that claimed 800,000 lives. Historian Drew Gilpin Faust called it a “Republic of Suffering.”

But the passions cut deeper than pride of place.

From its inception, Decoration Day (later Memorial Day) was linked to “Yankee” losses in the cause of emancipation.

Calling for the first formal Decoration Day, Union General John Logan wrote, “Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains…”

Leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, Logan set the first somber commemoration on May 30, 1868, in Arlington Cemetery, the sacred space wrested from property once belonging to Robert E. Lee’s family.( When Memorial Day was No Picnic by James M. McPherson.)

In other words, Logan’s first Decoration Day was divisive— a partisan affair, organized by northerners.

In 1870, Frederick Douglass gave a Memorial Day speech in Arlington that focused on this division:

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

Needing to mourn their losses, southern states created their own Confederate Decoration Days with grave decoration and picnics afterwards becoming annual rites. But the question remains: what inspired Logan to call for this rite of decorating soldier’s graves with fresh flowers?

The simple answer is—his wife.

While visiting Petersburg, Virginia – which fell to General Grant 150 years ago in 1865 after a year-long, deadly siege – Mary Logan learned about the city’s women who had formed a Ladies’ Memorial Association. Their aim was to show admiration “…for those who died defending homes and loved ones.”

Choosing June 9th, the anniversary of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” in 1864, a teacher had taken her students to the city’s cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen. General Logan’s wife wrote to him about the practice. Soon after, he ordered a day of remembrance.

The teacher and her students, it is worth noting, had placed flowers and flags on both Union and Confederate graves.

On this Memorial Day, as America wages its partisan wars at full pitch, this may be a lesson for us all.

More resources at the New York Times Topics archive of Memorial Day articles

The story of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” is told in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books Random House Audio)

© 2015 Kenneth C. Davis

May 21, 2015

War and Remembrance: Reflections on Memories and Memorial Day

War and Remembrance (Revised from May 25,2014 post)

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

–Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address

The souvenir is more than fifty years old. It is a wooden toy revolver. The legend stamped on the barrel reads, “JULY 1, 2, 3, 1863 Gettysburg, Pa.”

Toy wooden revolver from Gettysburg Battlefield-1963

(Author Photo)

I keep it nearby, on my desk—a reminder of what it felt like to be a nine-year-old boy standing for the first time in the fields at Gettysburg. I was certainly too young to understand what the war was about then and the details of what had happened in those fields and rock-strewn hills 100 years earlier. But I certainly was old enough to know that something special had happened there. I probably didn’t understand what Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address meant. But I felt in my young soul that I was on the ground he called “hallowed.”

The approach of another Memorial Day, as always, comes with thoughts of duty, honor, courage, sacrifice and loss. The holiday, the most somber date on the American national calendar, was born in the ashes of the Civil War as “Decoration Day,” when General John S. Logan –a-veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, a prominent Illinois politician and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union fraternal organization –called for May 30, 1868 as the day on which the graves of fallen Union soldiers would be decorated with fresh flowers.

“We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds.”

General John S. Logan’s General Order Number 11 (May 5, 1868)

Pointedly, Logan’s order was seen as a day to honor those who died ending slavery and opposing the “rebellion.”

Logan was inspired by the tradition of decorating graves by the women of Petersburg, Virginia. His wife told him of this ritual in March 1868 and Logan made his call for a “Decoration Day” that May. The events leading to this ritual in Petersburg are detailed in Chapter Two of THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

It was with that sense of war and remembrance of the Union war dead that families of Confederate soldiers were kept out of Arlington National Cemetery –a cemetery built on land confiscated during the war from Confederate General Robert E. Lee of Virginia. In response, Confederate states began to mark their own “Decoration” or Memorial Days.

From its beginnings, Decoration Day or Memorial Day, brought division. We can do better.

The Hidden History of America At War (Hachette Books Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much About® Memorial Day

(This video was originally posted May 2012. It was produced, edited and directed by Colin Davis.)

Memorial Day brings thoughts of duty, honor, courage, sacrifice and loss. The holiday, the most somber date on the American national calendar, was born in the ashes of the Civil War as “Decoration Day,” when General John S. Logan –a-veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, a prominent Illinois politician and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union fraternal organization –called for May 30, 1868 as the day on which the graves of fallen Union soldiers would be decorated with fresh flowers.

“We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds.”

Pointedly, Logan’s order was seen as a day to honor those who died in the cause if ending slavery and opposing the “rebellion.”

Every year at this time, I spend a lot of time talking about the roots and traditions of Memorial Day.

It’s not about the barbecue or the Mattress Sales. Obscured by the holiday atmosphere around Memorial Day is the fact that it is the most solemn day on the national calendar. This video tells a bit about the history behind the holiday.

One way to mark Memorial Day is by simply reading the Gettysburg Address. Here is a link to the Library of Congress and its page on the Address. I also discussed Memorial Day in a previous post.

One of the most famous symbols of the loss on Memorial Day is the Poppy, inspired by this World War I poem by John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields”

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe!

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high!

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.Source: The poem is in the public domain courtesy of Poets.org

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

Have a memorable Memorial Day!

(Images in video:Courtesy of the Library of Congress and Flanders Cemetery image Courtesy of the American Battle Monuments Commission)

May 20, 2015

June 6-Appearing at Printers Row Lit Fest

On Saturday June 6, I will be taking part in the Printers Row Lit Fest in Chicago. This two-day event is a book lover’s paradise. I will e speaking at 2 PM Saturday.

For more information about the Festival and the schedule of writers who are a

ppearing, check out the Printers Row site.