Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 5

October 8, 2024

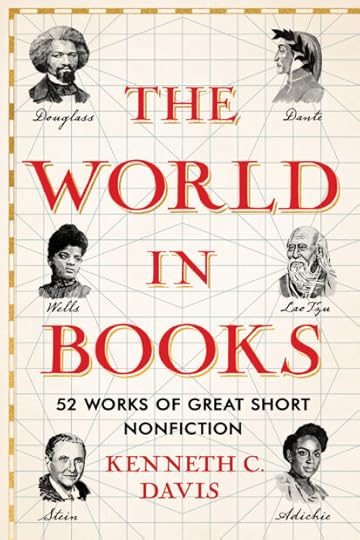

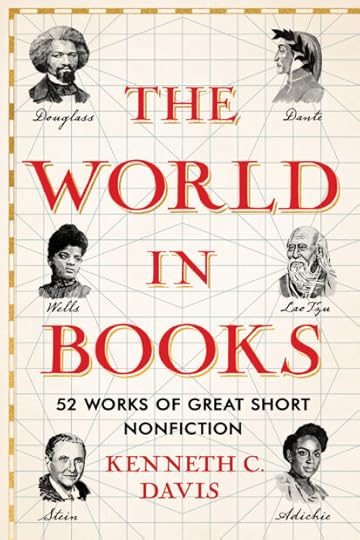

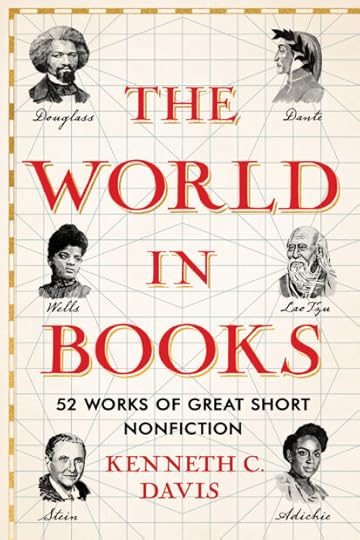

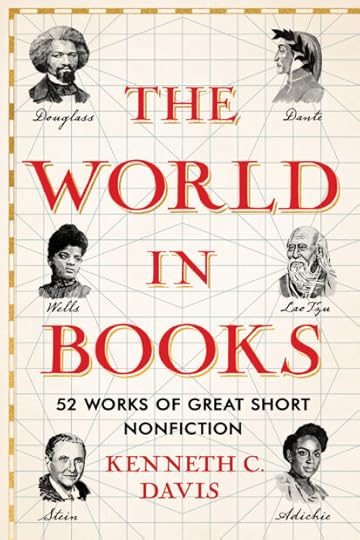

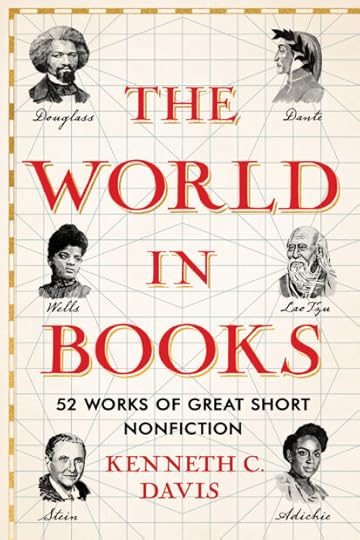

The World in Books-Now Available

THE WORLD IN BOOKS:

52 Works of Great Short Nonfiction

Named to “The Most Anticipated: The Great Fall 2024 Preview” by The Millions

First Trade review from Kirkus Reviews

“A wealth of succinct, entertaining advice.” Full review

Now out from Scribner Books and Simon & Schuster Audio on October 8, 2024. Read more and preorder copies here.

More advance Praise for The World in Books:

“Kenneth C. Davis’s The World in Books is a testament to both the beauty and power of the written word. And also, a very smart guide to books that have changed the way we think – and sometimes even changed us.”

–Deborah Blum, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century and the bestseller, The Poisoner’s Handbook.

“In his accessible, well-written, and unanticipatedly humorous The World in Books, Kenneth C. Davis takes readers on a journey that highlights fifty-two short yet provocative works of non-fiction. Highlighting both traditional favorites and contemporary classics, Davis offers his sharp insights in ways that appeal to the inquisitive mind, regardless of its familiarity with the selected texts. His poignant “Introduction” sets the stage for the contemporary relevance of why books like these matter in contemporary times, which makes this collection all the more relevant. Highly recommended for every person who treasures the freedom to read and values the transformative power it has for us all.”

—Dr. J. Michael Butler, Kenan Distinguished Professor of History, Flagler College and author of Beyond Integration

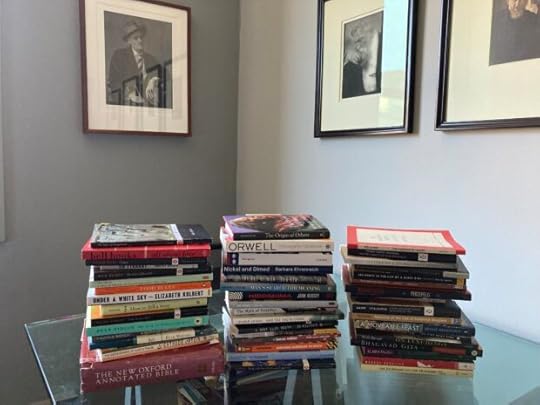

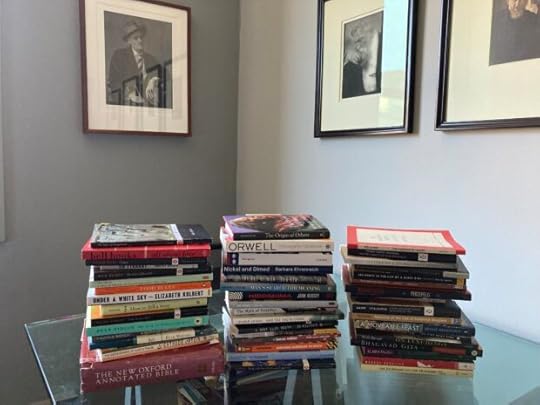

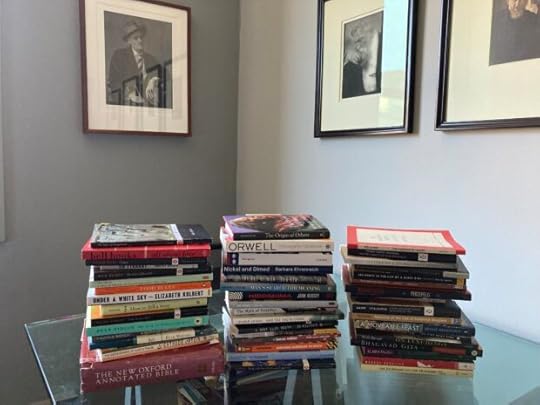

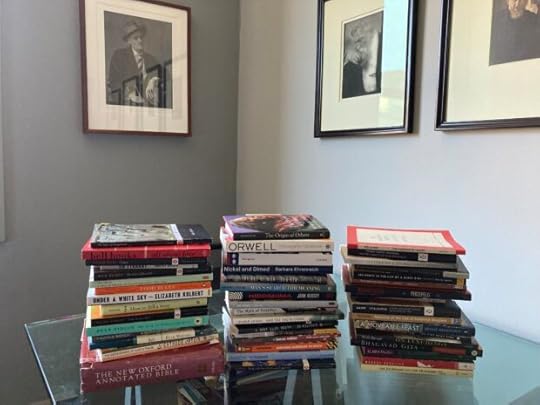

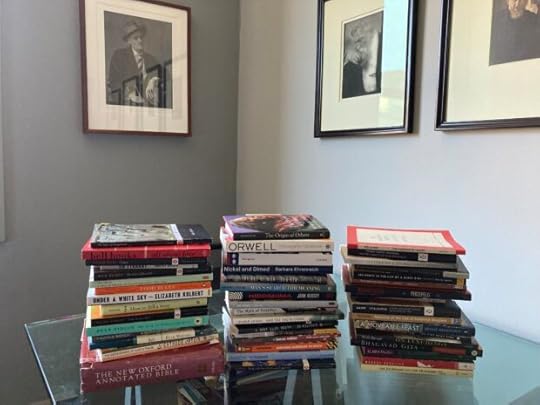

What a “Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like….

Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis

Among the 52 titles I have included are The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, the poetry of Sappho, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and such profoundly influential writers as Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Helen Keller, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Timothy Snyder.

The essential message of this book is that books matter–now more than ever. We must continue to educate ourselves. I believe that Open Books Open Minds.

I look forward to talking about this book in the coming months and sharing my fundamental belief that books can change us and the world.

In the meantime, please read and enjoy Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly

The post The World in Books-Now Available first appeared on Don't Know Much.

The World in Books- Out Today October 8, 2024

THE WORLD IN BOOKS:

52 Works of Great Short Nonfiction

Named to “The Most Anticipated: The Great Fall 2024 Preview” by The Millions

First Trade review from Kirkus Reviews

“A wealth of succinct, entertaining advice.” Full review

Now out from Scribner Books and Simon & Schuster Audio on October 8, 2024. Read more and preorder copies here.

More advance Praise for The World in Books:

“Kenneth C. Davis’s The World in Books is a testament to both the beauty and power of the written word. And also, a very smart guide to books that have changed the way we think – and sometimes even changed us.”

–Deborah Blum, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century and the bestseller, The Poisoner’s Handbook.

“In his accessible, well-written, and unanticipatedly humorous The World in Books, Kenneth C. Davis takes readers on a journey that highlights fifty-two short yet provocative works of non-fiction. Highlighting both traditional favorites and contemporary classics, Davis offers his sharp insights in ways that appeal to the inquisitive mind, regardless of its familiarity with the selected texts. His poignant “Introduction” sets the stage for the contemporary relevance of why books like these matter in contemporary times, which makes this collection all the more relevant. Highly recommended for every person who treasures the freedom to read and values the transformative power it has for us all.”

—Dr. J. Michael Butler, Kenan Distinguished Professor of History, Flagler College and author of Beyond Integration

What a “Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like….

Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis

Among the 52 titles I have included are The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, the poetry of Sappho, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and such profoundly influential writers as Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Helen Keller, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Timothy Snyder.

The essential message of this book is that books matter–now more than ever. We must continue to educate ourselves. I believe that Open Books Open Minds.

I look forward to talking about this book in the coming months and sharing my fundamental belief that books can change us and the world.

In the meantime, please read and enjoy Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly

The post The World in Books- Out Today October 8, 2024 first appeared on Don't Know Much.

October 4, 2024

The World in Books-Coming in October 2024

THE WORLD IN BOOKS:

52 Works of Great Short Nonfiction

Named to “The Most Anticipated: The Great Fall 2024 Preview” by The Millions

First Trade review from Kirkus Reviews

“A wealth of succinct, entertaining advice.” Full review

Coming from Scribner Books on October 8, 2024. Read more and preorder copies here.

More advance Praise for The World in Books:

“Kenneth C. Davis’s The World in Books is a testament to both the beauty and power of the written word. And also, a very smart guide to books that have changed the way we think – and sometimes even changed us.”

–Deborah Blum, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century and the bestseller, The Poisoner’s Handbook.

“In his accessible, well-written, and unanticipatedly humorous The World in Books, Kenneth C. Davis takes readers on a journey that highlights fifty-two short yet provocative works of non-fiction. Highlighting both traditional favorites and contemporary classics, Davis offers his sharp insights in ways that appeal to the inquisitive mind, regardless of its familiarity with the selected texts. His poignant “Introduction” sets the stage for the contemporary relevance of why books like these matter in contemporary times, which makes this collection all the more relevant. Highly recommended for every person who treasures the freedom to read and values the transformative power it has for us all.”

—Dr. J. Michael Butler, Kenan Distinguished Professor of History, Flagler College and author of Beyond Integration

What a “Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like….

Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis

Among the 52 titles I have included are The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, the poetry of Sappho, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and such profoundly influential writers as Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Helen Keller, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Timothy Snyder.

The essential message of this book is that books matter–now more than ever. We must continue to educate ourselves. I believe that Open Books Open Minds.

I look forward to talking about this book in the coming months and sharing my fundamental belief that books can change us and the world.

In the meantime, please read and enjoy Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly

The post The World in Books-Coming in October 2024 first appeared on Don't Know Much.

September 19, 2024

Who Said It? 10/28/2021

President Dwight D. Eisenhower (June 14, 1953)

President Eisenhower (Courtesy: Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum)

In 1953, Senator Joseph McCarthy, with assistance from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, campaigned to suppress books hinting at any connection to Socialism or Communism.

In April 1953, two of McCarthy’s underlings, Roy Cohn and David Schine, were dispatched to Europe, partly to scour U.S. Information Service libraries. Created to provide war-ravaged countries with American books, these collections – McCarthy claimed – held thousands of works by Communists. Intimidated by McCarthy’s men, foreign service officials removed titles by, among others, the blacklisted writers Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Howard Fast.

Reluctant to challenge the powerful Senator, Eisenhower offered these words to a commencement audience at Dartmouth:

Look at your country. Here is a country of which we are proud, as you are proud of Dartmouth and all about you, and the families to which you belong. But this country is a long way from perfection–a long way. We have the disgrace of racial discrimination, or we have prejudice against people because of their religion. We have crime on the docks. We have not had the courage to uproot these things, although we know they are wrong. And we with our standards, the standards given us at places like Dartmouth, we know they are wrong.

Now, that courage is not going to be satisfied–your sense of satisfaction is not going to be satisfied, if you haven’t the courage to look at these things and do your best to help correct them, because that is the contribution you shall make to this beloved country in your time. Each of us, as he passes along, should strive to add something.

It is not enough merely to say I love America, and to salute the flag and take off your hat as it goes by, and to help sing the Star Spangled Banner. Wonderful! We love to do them, and our hearts swell with pride, because those who went before you worked to give to us today, standing here, this pride.

And this is a pride in an institution that we think has brought great happiness, and we know has brought great contentment and freedom of soul to many people. But it is not yet done. You must add to it.

Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency. That should be the only censorship.

“Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement Exercises”

Source and complete text: Dwight D. Eisenhower, Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement Exercises, Hanover, New Hampshire. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project

It is also worth noting that Eisenhower’s words did not translate into much action. U.S. Information Services libraries were stripped of thousands of titles.

The post Who Said It? 10/28/2021 first appeared on Don't Know Much.

When Robin Hood Was Blacklisted

(Originally posted in 2022; updated September 19, 2024)

“The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

American Library Association “Freedom to Read” Statement, first issued on June 25, 1953.

“This is a dangerous time for readers and the public servants who provide access to reading materials. Readers, particularly students, are losing access to critical information, and librarians and teachers are under attack for doing their jobs.”

– Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom

Banned Books Week 2024 is marked from September 22-28, 2024

Book censorship is as American as apple pie, slavery, and lynching. This post offers a brief overview of book banning in America.

Robin Hood was a Commie.

That, at least, is what an Indiana state textbook commissioner thought back in 1953. This official called for schools to ban books mentioning Robin Hood for the simple reason that Robin and his Merry Men robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Their antics reeked suspiciously of godless Socialism.

It is easy to laugh off this overlooked history as an amusing bit of trivia. Except the Hoosier state assault on Robin Hood was part of a larger nationwide effort to ban books and suppress intellectual freedom. It was led by Senator Joseph McCarthy during the anti-Communist “witch hunts.” It targeted books, writers, and libraries both at home and around the world. And it holds pointed lessons about safeguarding democracy from the forces threatening it today.

After the 1947 blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten” screenwriters by the House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC), Senator McCarthy emerged as the face and unrelenting voice of a crusade against Communist influences in America. In 1950, McCarthy claimed to possess an extensive list of Communists who worked in the State Department. Launching his war on alleged Communist infiltrators as chairman of a Senate committee on government operations, McCarthy was abetted by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. To be labeled a Communist was an accusation from which there was no escape. Claims of innocence or invoking the Fifth Amendment were tantamount to confession.

Set against the Korean War begun in 1950, and with the convictions of Alger Hiss that year for perjury over espionage and the Rosenbergs in 1951 for atomic spying, America’s fear of Communism spread like wildfire. Gaining an army of rabid followers, McCarthy’s crusade to root out subversives widened to focus intently on libraries, which were pressured to purge their collections of works by Marx. By 1952, the New York Times described a pervasive wave of educational book censorship in America. Around the country, self-appointed local committees— “volunteer educational dictators” in the words of one librarian—were coercing librarians to remove books considered “un-American,” the Times found.

This anti-Communist juggernaut was not only steam-rolling domestic libraries. McCarthy sent it on a road trip. In April 1953, McCarthy’s underlings, attorney Roy Cohn and associate David Schine, were dispatched to Europe. Part of their mission was to scrutinize U.S. Information Service libraries, created to provide war-ravaged countries with American books. McCarthy claimed that these collections held thousands of works by Communists. Targeting suspect authors, just as Hollywood had been purged of “Red” screenwriters, Cohn and Schine succeeded in intimidating foreign service officials. No fires were set, but titles by Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Howard Fast, among others, were pulled from the shelves.

Inaugurated in January 1953, President Eisenhower was hesitant to challenge McCarthy. But he discreetly fired back. He told a Dartmouth commencement audience in June of that year:

“Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency.”

–President Eisenhower, “Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement”

Unfortunately, Eisenhower’s defense of reading was less than full-throated. Ultimately, his State Dept. folded to McCarthy’s men.

“Only reckless men, under these conditions, could choose to take steps offensive to McCarthy since the President and the Secretary [of State John Foster Dulles] have rarely backed up their subordinates whom McCarthy has singled out for attack.”

—The New Republic June 29, 1953

But America’s librarians were not about to be silenced. Despite the stale caricature of an old lady in a bun shushing the patrons, many librarians spoke out, daringly, given the nation’s fearful mood and threats to their jobs. Responding to this mounting pressure, the American Library Association (ALA), in concert with the American Association of Publishers, issued on June 25, 1953 a “Freedom to Read” statement –since revised several times—that begins, “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

Unfortunately, the ALA was right then—and now. Ike’s “book burners” are back—or perhaps it is more accurate to say they never left. Across America, a concerted effort to purge school and public libraries of “offensive” literature has found new vigor and a louder voice. There is a long history of attempts to rid libraries of books considered objectionable—it is the reason the ALA launched its annual Banned Books Week in 1982 ago to highlight local challenges to books. But these perennial community-level attempts to challenge books deemed “subversive” or “indecent” have reached a new level of intensity.

Currently, in America’s riven political ecosystem, the hyper-charged urge to purge has been fused with anger over vaccinations and mask mandates and the assault on teaching any American history that doesn’t fit a suitably patriotic mold. In such states as Florida, Texas, and Virginia, the backlash has grown intense and been wrapped in the pretense of giving parents “control” over their children’s education. The bullseye has moved from Robin Hood, The Communist Manifesto, and The Catcher in the Rye to a new set of targets. Many of the books now under fire deal with race, slavery, gender issues, and of course, sexuality.

Raising the fever pitch are books exploring gay relationships and gender identity. In November 2021, a Virginia school board member was quoted in press reports as saying, “I think we should throw those books in a fire.”In February, a Tennessee pastor went further, leading a book burning that saw Harry Potter and Twilight consigned to the flames—both among the usual suspects in recent book bans and challenges.

We’ve seen these flames before. In fiction, they raged in Ray Bradbury’s dystopic Fahrenheit 451 in which “firemen” burn outlawed books. Bradbury’s 1953 novel was written in large part as a reaction to the ongoing purges under McCarthy and his followers.

But these flames have also roared more frighteningly in fact. Book burnings are actually older than books, dating to ancient times in Greece and China. After Gutenberg’s printing revolution, the Vatican created the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a catalog of banned books, some of which were burned, sometimes along with their authors—like Giordano Bruno in 1600.

Most notoriously in pre-World War II Germany, some 25,000 “un-German” books were consigned to Nazi bonfires in May 1933. Targeted by Hitler’s loyal disciples were works by German Jews and Marx, Freud, and Einstein. Books by German novelists Thomas Mann and Eric Maria Remarque—author of the World War I classic All Quiet on the Western Front— went into the flames along with such American writers as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Helen Keller.

Book Burning May 10, 1933 Image courtesy US Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/conten...

Can it happen here? It has.

Nearly a century before the Nazi book burnings, a concerted effort to flood the slaveholding states with abolitionist literature was met with fire. In the summer of 1835, an angry mob raided a Charleston, South Carolina post office and consigned thousands of abolitionist pamphlets to a bonfire. The book burning was topped off with an effigy of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison being set ablaze. Garrison was lucky. Tragically, abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy was not. Two years later, a mob intent on burning anti-slavery literature in Alton, Illinois murdered Lovejoy as he tried to defend his presses. A century later, in 1939, California growers burned Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath.

Scrubbing the nation’s public square of “offensive” materials and torching books—despite the protections in the Bill of Rights—are as American as apple pie, lynch mobs, burning crosses, and now, tiki torches.

But there’s something new in the equation. The latest wave of book suppression is not simply about “subversion” or “dirty words.” Scratch the surface of recent book bans and it is clear that the assault on free expression cannot be separated from the larger Orwellian effort to sanitize American history, delegitimize literature by gay writers and people of color, and undermine democracy.

This revitalized onslaught carries the distinct whiff of white, Christian nationalism. This is the racial, cultural, and political ideology that once reared its head as nineteenth-century Nativism, the reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, and the America Firsters of the 1930s.

Claiming that the United States is a “Christian nation,” this strand of anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic American DNA is older than the nation itself. Time has not diminished its power. Now adding “globalists” to their enemies list, white Christian nationalism has been tied to the Charlottesville rioters who chanted “You will not replace us” and the January 6 insurrection by experts who study the movement.

America has no monopoly on this historically powerful faction. A form of white Christian nationalism, with its claims of racial superiority, certainly fed Hitler’s rise in Germany.

And that is why this revived wave of book suppression is a piece of a much larger development. The reason that Maus, a Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel-memoir about the Holocaust, was ostensibly pulled from schools in Tennessee was for some of its language and a discreet cartoon illustration of the author’s mother—an Auschwitz survivor—naked in the bathtub where she had committed suicide. But its critics apparently sought a kinder, gentler discussion of the Holocaust, although any attempts to soften that history tiptoe dangerously toward denialism. This is how history goes down 1984’s “Memory Hole.”

It is more than a little ironic that this onslaught of suppression comes as many on the Right decry the so-called “cancel culture” of the Left. Claiming their right to free speech is under attack, modern-day “book burners” crush that freedom under their boot heels as they attempt to distort or erase history and silence unwelcome voices. When such voices and ideas are deemed a threat and suppressed by the government, religious authorities, or a political party, we teeter on the thin ice of authoritarianism. The ice cracks when a fictional character is attacked—whether it is Homer Simpson, Huckleberry Finn, or Robin Hood. All three have come under fire over the years.

Banning books, legislating against “divisive concepts” in history class, and purging diversity all come straight from the playbook of the Strongman. He knows the power of the pen. Books make us think. Literature cultivates the free mind. Writers are truth-tellers. In 1917, Soviet leader Lenin ordered a “Decree on Press” threatening closure of publications critical of the Bolsheviks. Authoritarians know the danger posed by truth. And they are more than willing to use sword and flame to cut it down.

The question is what can we do about it?

“The antidote to authoritarianism is not some form of American authoritarianism,” Cooper Union librarian David K. Berninghausen told the Times in 1952. “The antidote is free inquiry.”

When Robin Hood was threatened by a textbook commissioner in 1953, some Indiana State University students fought back. Five of them gathered chicken feathers, dyed them green, and spread them across campus. Their protest caught on at other colleges, including UCLA, where two hundred students dressed up as Sherwood Forest’s Merry Men for a Green Feather drop. A clever, well-aimed protest, the Green Feather movement broke no windows or legs. Robin Hood was spared.

But those more innocent days are gone. In the internet age, the lines are more sharply drawn, sides set in stone, and the stakes much higher.

That is why dumping some green feathers or wearing an “I READ BANNED BOOKS” t-shirt will not be enough for this moment. If we care, we must take to heart Ike’s advice and “read every book.” We must firmly resolve to read. But buying and reading Maus or Toni Morrison’s Beloved are only the first steps.

We have to make sure that others can read these books. We must be audacious in support of free libraries and vigorously support all teachers who want to encourage students to read, debate, and think for themselves. And we must vigilantly push back on politicians and schoolboards purging libraries of uncomfortable truths. A few loud voices dominating a schoolboard or town hall meeting do not a majority make. To allow a noisy minority to dictate what we read and teach is skating on that thin ice of totalitarian loyalty oaths typical of a Mussolini or Stalin.

On this final note, history is clear. When you have succeeded in marking a writer as “degenerate” or “immoral”—as the Nazis did—you have moved towards dehumanizing them. It is a few short perilous steps from censorship to suppression to a conflagration far worse. In Berlin, on the spot where Nazis threw books into a bonfire, there is a plaque citing German playwright Heinrich Heine’s 1820 words, which read in part: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

The road to Hell is lit by burning books.

UPDATE: “From School Librarian to Activist”

“Amid a surge in book bans nationwide, the librarian Amanda Jones was targeted by vicious threats. So she decided to fight back.”

UPDATE: “Virginia Legal Action Threatens the Freedom to Read” (National Coalition Against Censorship)

“This legal action could profoundly limit the availability of books in the Commonwealth of Virginia. No book has been banned for obscenity in the United States in more than 50 years. Prohibiting the sale of books is a form of censorship that cannot be tolerated under the First Amendment.”

I am also linking to this article from American Libraries, a publication of the American Library Association; “Same Fight, New Tactics,” which offers tips for meeting challenges to books in libraries.

Here are some key organizations leading the fight against book bans and other forms of censorship:

National Coalition Against Censorship

American Library Association (ALA) Office of Intellectual Freedom (OIF)

ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) “What is Censorship?

© Copyright 2022, 2023, 2024 Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

The post When Robin Hood Was Blacklisted first appeared on Don't Know Much.

September 5, 2024

The World in Books-Coming in October 2024

I am very excited to announce the publication of my latest work:

THE WORLD IN BOOKS:

52 Works of Great Short Nonfiction

First Trade review from Kirkus Reviews

“A wealth of succinct, entertaining advice.” Full review

Coming from Scribner Books on October 8, 2024. Read more and preorder copies here.

More advance Praise for The World in Books:

“Kenneth C. Davis’s The World in Books is a testament to both the beauty and power of the written word. And also, a very smart guide to books that have changed the way we think – and sometimes even changed us.”

–Deborah Blum, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century and the bestseller, The Poisoner’s Handbook.

“In his accessible, well-written, and unanticipatedly humorous The World in Books, Kenneth C. Davis takes readers on a journey that highlights fifty-two short yet provocative works of non-fiction. Highlighting both traditional favorites and contemporary classics, Davis offers his sharp insights in ways that appeal to the inquisitive mind, regardless of its familiarity with the selected texts. His poignant “Introduction” sets the stage for the contemporary relevance of why books like these matter in contemporary times, which makes this collection all the more relevant. Highly recommended for every person who treasures the freedom to read and values the transformative power it has for us all.”

—Dr. J. Michael Butler, Kenan Distinguished Professor of History, Flagler College and author of Beyond Integration

What a “Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like….

Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis

Among the 52 titles I have included are The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, the poetry of Sappho, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and such profoundly influential writers as Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Helen Keller, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Timothy Snyder.

The essential message of this book is that books matter–now more than ever. We must continue to educate ourselves. I believe that Open Books Open Minds.

I look forward to talking about this book in the coming months and sharing my fundamental belief that books can change us and the world.

In the meantime, please read and enjoy Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly

The post The World in Books-Coming in October 2024 first appeared on Don't Know Much.

September 4, 2024

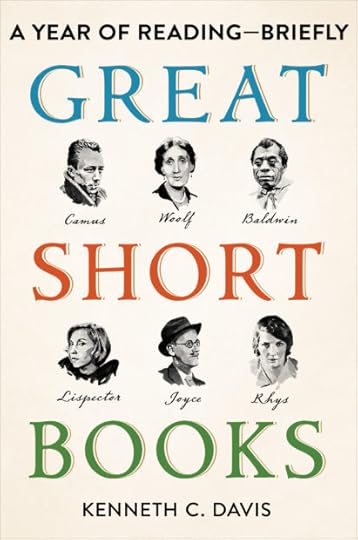

GREAT SHORT BOOKS: A Year of Reading–Briefly

NOW IN PAPERBACK

GREAT SHORT BOOKS:

A YEAR OF READING — BRIEFLY

Scribner/Simon & Schuster and Simon Audio (Unabridged audio download)

“An exciting guide to all that the world of fiction has to offer in 58 short novels — from ‘The Great Gatsby’ and ‘Lord of the Flies’ to the contemporary fiction of Colson Whitehead and Leïla Slimani — that, ‘like a first date,’ offer pleasure and excitement without commitment.” New York Times Book Review

Booklist “Editors’ Choice Adult Books 2022″

“…The most exceptional of the best books of 2022 reviewed in Booklist…”

“Delightfully accessible, Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly presents 58 fact-filled reviews of short books, a smorgasbord of titles sure to entice readers.” –Cheryl McKeon, Shelf Awareness

“I consider Davis’ ‘Great Short Books’ a gift to readers, a true treasure trove of literary recommendations.” —Sue Gilmore, SFGate

“Anyone who’s eternally time-strapped will treasure Kenneth C. Davis’ Great Short Books. This nifty volume highlights 58 works of fiction chosen by Davis for their size (small) and impact (enormous). Each brisk read weighs in at around 200 pages but has the oomph of an epic.” —Bookpage Full Review

“An entertaining journey with a fun, knowledgeable guide…. “ Kirkus Reviews

“A must-purchase for public and school libraries.” ALA Booklist

FIRST TRADE REVIEWS FROM KIRKUS, PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, BOOKLIST

“Davis feels that novels of 200 pages or less often don’t get the recognition they deserve, and this delightful book is the remedy…A must-purchase for public and school libraries.” *Starred Booklist review

“An entertaining journey with a fun, knowledgeable guide…. His love of books and reading shines through. From 1759 (Candide) to 2019 (The Nickel Boys), he’s got you covered.” –Kirkus Reviews

Full KIRKUS review here

“Davis’s conversational tone makes him a great guide to these literary aperitifs. This is sure to leave book lovers with something new to add to their lists.” FULL PUBLISHERS WEEKLY REVIEW here

During the lock-down, I swapped doom-scrolling for the insight and inspiration that come from reading great fiction. Inspired by Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” and its brief tales told during a pandemic, I read 58 great short novels –not as an escape but an antidote.

“A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more. It can lead to greater possibilities. But there is no long-term commitment.”

–From “Notes of a Common Reader,” the Introduction to Great Short Books

Read “The Antidote to Everything,” an excerpt from the Introduction published on Lit Hub

The result is a compendium that goes from “Candide” to Colson Whitehead, and Edith Wharton to Leïla Slimani. And yes, Maus and many other Banned Books and Writers.

What “A Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like

Voltaire in Great Short Books

Art © Sam Kerr

Edith Wharton in Great Short Books

Art © Sam Kerr

Advance Praise for Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—Briefly

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a fascinating, thoughtful, and inspiring guide to a marvelous form of literature: the short novel. You can dip into this book anywhere you like, but I found myself reading it cover-to-cover, delighting in discovering new works while also revisiting many of my favorites. GREAT SHORT BOOKS is itself a great book—for those who are over-scheduled but want to expand their reading and for those who will simply delight in spending time with a passionate fellow reader who on every page reminds us why we need and love to read.”

–Will Schwalbe, New York Times bestselling author of THE END OF YOUR LIFE BOOK CLUB

“This is the book that you didn’t know you really needed. I began digging into this book as soon as I got it, and it was such a delight to read beautiful prose, just a sip at a time, with Kenneth Davis’ notes to give me context and help me more fully appreciate the stories. Keep this book near your bed or on your coffee table. It will be read and loved.”

–Celeste Headlee, journalist and author of WE NEED TO TALK and SPEAKING OF RACE

Recording audio book of Great Short Books (Sept. 2022) Photo by Katherine Cook

From hard-boiled fiction to magical realism, the 18th century to the present day, Great Short Books spans genres, cultures, countries, and time to present a diverse selection of acclaimed and canonical novels—plus a few bestsellers. Like browsing in your favorite bookstore, this eclectic compendium is a fun and practical book for any passionate reader hoping to broaden their collection— or anyone who is looking for an entertaining, effortless reentry into reading.

Listen to a sample of the audio book of Great Short Books

And Indie booksellers weigh in:

“Need something grand, something classic, uh…. something short to read, but don’t know where to start? Check out Kenneth Davis’s guide to Great Short Books and you’ll soon find just the right tale to delight your literary palate. For each suggestion, Davis gives us first lines, a plot summary, an author’s bio, a reason for reading it, and, finally, what you should read next from the author’s canon. Pick up a copy… you’ll be glad you did. You’re welcome!”—Linda Bond, Auntie’s Bookstore (Spokane, WA)

“Kenneth Davis has presented the perfect solution for too many books, not enough time—a collection of exceptional short books perfect for reading in a society seemingly without any free time. Many of the books may be familiar by name, some are obscure, some even forgotten, but all belong in the canon of superb literature. He teases with a brief synopsis and explains why each book deserves attention. An absolutely intriguing bonus is a short biographical sketch of each author, many of whom had fascinating but traumatic lives. It is the perfect book to provide comfort literature for busy readers.”—Bill Cusumano, Square Books (Oxford, Miss.)

More early reviews from readers at NetGalley.com

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a wonderful, breezy but deep look at the outstanding short books of the last 150 years. Kenneth C. Davis is a genius at summarizing each book and making the reader want to read said book post haste. This is a book I didn’t know the world needed but the world did.” –Tom O., reviewer

“…an incredibly valuable tool for book clubs and readers everywhere! Some authors/titles are well-known and others will be new discoveries….HIGHLY RECOMMENDED for any book group looking to find new titles or any reader who wants to know what to read next.” –Ann H. reviewer

“I found over a dozen new authors or titles I want to now read that were included in his main list, and the Further Reading at the end of each chapter and at the end of the volume itself.

As others have suggested, this is a great tool for Book Clubs!

Not Lit Crit, it is mostly focused on necessary, just-the-facts-mam information on one person’s reading of short books over a year. Well worth a read, and great for browsing!” –Stephen B., Librarian

“What better way to introduce new readers to more than 50 ‘short’ books. This handy book is full of non-spoiler descriptions and cultural context that situate these stories within our world.” –Kelsey W., librarian

S0urce: Great Short Books via NetGalley

I can’t wait to start talking about this book with readers everywhere.

Teachers, Librarians, Book Clubs and Other Learning Communities:

Invite me for a visit to your school, classroom, library, historical group, book club or conference.

The post GREAT SHORT BOOKS: A Year of Reading–Briefly first appeared on Don't Know Much.

August 31, 2024

Who Said It? (Labor Day edition)

(Reposted from 2014)

Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (“State of the Union”) December 3, 1861

It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life.

Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless.

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights.

Source and Complete text: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” Read more about Lincoln, his life and administration and the Civil War in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the Civil Warand Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Labor Day became a federal holiday on September 3, 1894.

Read about the history of Labor Day in this post.

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

The post Who Said It? (Labor Day edition) first appeared on Don't Know Much.

August 30, 2024

Labor Day 2024

[Post updated August 30, 2024]

To most Americans, the first Monday in September means a three-day weekend and the last hurrah of summer, a final outing at the shore before school begins, a family picnic. The federal Labor Day was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland during his second term in 1894.

130 years later, organized American labor has seen its ups and downs. But recently, unions have had a comeback, helped in part by the most pro-labor Administration in modern history.

As a U.S Dept of Labor blog put it:“Unionized workers made significant gains through their collective action during the past 12 months:

The United Auto Workers notched two major victories for workers – historic new contracts with the Big Three automobile manufacturers and an organizing win at the Chattanooga, Tennessee Volkswagen plantSeveral Hollywood entertainment unions representing actors, writers, production crews, musicians and other craftspeople reached new deals with the film and television industry that contained significant economic advances as well as protections for their members from the increasing use of artificial intelligenceLabor unions representing pilots and flight attendants continued to deliver on their promises to their members by negotiating contracts that buoyed the economic securityof airline industry workers.The International Brotherhood of Teamsters reached a new 5-year contract with Anheuser-Busch, boosting pay, benefits and job security for about 5,000 union-represented employees.Source: US. Dept. of Labor blogLabor suddenly has muscle. After years of struggles, workers have begun on a grassroots level to organize unions at such places REI, Trader Joe’s, Starbucks, Amazon warehouses, and a LA topless bar. And for the first time in many years, Labor has a friend in the White House. President Biden and Vice President Harris–now the Democratic nominee for Preisdent — joined a United Auto Workers picket line last year.A 2023 White House fact sheet read:

“President Biden promised to be the most pro-worker and pro-union President in American history, and he has kept that promise. Support for unions is at its highest level in more than half a century, inflation-adjusted income is up 3.5% since the President took office, and the largest wage gains over the last two years have gone to the lowest-paid workers. ” Source: White House Fact Sheet

But as we rethink work and life, it is a most fitting moment to consider how we labor and the history of Labor Day. The holiday was born at the end of the nineteenth century, in a time when work was no picnic. As America was moving from farms to factories in the Industrial Age, there was a long, violent, often-deadly struggle for fundamental workers’ rights, a struggle that in many ways was America’s “other civil war.” (From “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”)

“Glassworks. Midnight. Location: Indiana.” From a series of photographs of child labor at glass and bottle factories in the United States by Lewis W. Hine, for the National Child Labor Committee, New York.

The first American Labor Day is dated to a parade organized by unions in New York City on September 5, 1882, as a celebration of “the strength and spirit of the American worker.” They wanted among, other things, an end to child labor.

In 1861, Lincoln told Congress:

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation.

Today, in postindustrial America, Abraham Lincoln’s words ring empty. Labor is far from “superior to capital.” Working people and unions have borne the brunt of the great changes in the globalized economy.

But the facts are clear: In the current “gig economy,” the loss of union jobs and the recent failures of labor to organize workers is one key reason for the decline of America’s middle class.

Read the full history of Labor Day in this essay: “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day” (2011)

The post Labor Day 2024 first appeared on Don't Know Much.

August 27, 2024

The World in Books-Coming in October 2024

I am very excited to announce the publication of my latest work:

THE WORLD IN BOOKS:

52 Works of Great Short Nonfiction

First Trade review from Kirkus Reviews

“A wealth of succinct, entertaining advice.” Full review

Coming from Scribner Books on October 8, 2024. Read more and preorder copies here.

More advance Praise for The World in Books:

“Kenneth C. Davis’s The World in Books is a testament to both the beauty and power of the written word. And also, a very smart guide to books that have changed the way we think – and sometimes even changed us.”

–Deborah Blum, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century and the bestseller, The Poisoner’s Handbook.

“In his accessible, well-written, and unanticipatedly humorous The World in Books, Kenneth C. Davis takes readers on a journey that highlights fifty-two short yet provocative works of non-fiction. Highlighting both traditional favorites and contemporary classics, Davis offers his sharp insights in ways that appeal to the inquisitive mind, regardless of its familiarity with the selected texts. His poignant “Introduction” sets the stage for the contemporary relevance of why books like these matter in contemporary times, which makes this collection all the more relevant. Highly recommended for every person who treasures the freedom to read and values the transformative power it has for us all.”

—Dr. J. Michael Butler, Kenan Distinguished Professor of History, Flagler College and author of Beyond Integration

What a “Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like….

Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis

Among the 52 titles I have included are The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, the poetry of Sappho, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and such profoundly influential writers as Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Helen Keller, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Timothy Snyder.

The essential message of this book is that books matter–now more than ever. We must continue to educate ourselves. I believe that Open Books Open Minds.

I look forward to talking about this book in the coming months and sharing my fundamental belief that books can change us and the world.

In the meantime, please read and enjoy Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly

The post The World in Books-Coming in October 2024 first appeared on Don't Know Much.