Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 49

July 5, 2011

Bloodlust Writing Frenzy

Lately I've been kind of obsessed with finishing my new novel, which I'm still calling The Turing Chronicles. I'm around the final turn and in the last stretch.

It's kind of a 1950s invasion novel, involving a contagious mutation that makes people into telepathic shapeshifters. It includes two historical figures as main characters: the computer pioneer Alan Turing and the Beat writer William Burroughs.

Anyway, I've been using every spare minute to work on the novel, which is why I haven't been doing many blog posts lately. If I blog a lot, it's a pretty good sign that I'm not writing, and vice-versa. Although, of late, I continue tweeting even when I'm writing a lot—it's so easy to tweet a nice link or phrase that I find in my ongoing researches for a story or book.

Last week Sylvia and I were up in San Francisco for a couple of days and I took a few pictures.

The one above is the Bay Bridge seen from the Ferry Terminal at the end of Market Street. A lot of action here on Sundays, like the farmers market and lots of food. It always helps a bridge picture to have a sailboat in it. What I like the most are those gantry(?) cranes the background, from the port of Oakland, they load and unload containers from ships. They always remind me of giraffes.

We walked through Chinatown, on our way to our favorite Pho Noodle restaurant, the hole in the wall facing onto near the little square of park over the parking garage in front of the old Chinatown Holiday Inn. What makes the Golden Star great is that if you order Pho Ga (Pho with Chicken), the chicken is a broiled leg on the side, not a bunch of characterless white squares in the broth.

This is, like, my Nth picture of Chinatown. I always like the fire escapes and the brick walls and the people walking around.

Another Chinatown fire escape. I love the colors here, and the stripes of shadow and light. The world really is so remarkably intricate and beautiful.

Here's a simpler abstract pattern, maybe in Chinatown, maybe in Santa Cruz. For going on fifty years, I've been into taking pictures that fall into an assemblage of rectangular patterns. Finding the composition is always fun, and if you have good colors that's nice. Though faint pastels are good too, or you can play off the textures.

Sometimes I worry that I've taken pictures of everything I'd ever want to take a picture of, but if I carry my camera around, I'll see stuff, even though it's, in a way, the same old stuff as ever.

Like swirls of grass or cactus. These are in the Bezerkistan (excuse me, Berkeley) Botanical Garden, just up the hill from the football stadium that they're refurbishing. A steep $7 to get in, but really a lovely place.

Cactuses, too. My god, how many cactus pictures have I taken? This is a nice cactus though. I like the little "ears" on the lower lop-lop lobe.

Back in SF, there's a little park near Mason St. and California St., in front of the big Episcopal cathedral, I often walk up there when I have some spare time. Nice breeze up there, and they have a lovely Italianate fountain, complete with bronze turtles.

Good water coming off the fountain, too. Water's another thing I've photographed a zillion times. Sometimes I feel like I ought start shoving my lens into people's faces on the streets, or telephotoing them—and now and then I do that a little—sometimes I try and work to have a personality for street photography, but of course a lot of time, I don't want to work.

Well, here's one piece of light street photography, a mover in a van in Santa Cruz, you can't see his face, and he really does fill out the picture. Just that dolly isn't enough—I shot the picture first that way, and then with the guy in it, and with the guy it's much fuller.

I wrote a lot in the past week, working out many kinks in the outline for the ending, weaving in a lot of fixes, and writing maybe five thousand words of new material. I feel like I'm around the corner and into the home stretch. To use a more colorful and accurate metaphor, I feel like a primitive hunter in the woods.

I've been on the trail of this shaggy beast for five years, if I counting the preliminary first two chapters. It's wounded now, I can see more and more of its stains on the leaves, I can hear it in the underbrush up ahead, I'm pushing forward, heedless of the branches scratching my face, my whole being is focused on the task of taking down the beast at last, I want to bring it to the ground and tear out its throat to see it shudder and lie still, and to bathe my face in its last dribbles of ink, finishing my quest at last.

For the metaphor-impaired: Do understand that I'm speaking figuratively—in reality I've never hunted and, generally speaking, I even go out of my way to avoid killing insects. But a novel I've been actively working on for a year—and planning for five years—that's a beast I want to lay to rest.

My computer programmer friend John Walker used to speak of a "bloodlust hacking frenzy" when pulling long hours to finish a project. Bloodlust writing frenzy, yeah.

Home Stretch of "Turing Chronicles"

Lately I've been kind of obsessed with finishing my new novel, which I'm still calling The Turing Chronicles. I'm around the final turn and in the last stretch.

It's kind of a 1950s invasion novel, involving a contagious mutation that makes people into telepathic shapeshifters. It includes two historical figures as main characters: the computer pioneer Alan Turing and the Beat writer William Burroughs.

Anyway, I've been using every spare minute to work on the novel, which is why I haven't been doing many blog posts lately. If I blog a lot, it's a pretty good sign that I'm not writing, and vice-versa. Last week Sylvia and I were up in San Francisco for a couple of days and I took a few pictures.

The one above is the Bay Bridge seen from the Ferry Terminal at the end of Market Street. A lot of action here on Sundays, like farmer's market and lots of food. It always helps a bridge picture to have a sailboat in it. What I like the most are those gantry(?) cranes the background, from the port of Oakland, they load and unload containers from ships. They always remind me of giraffes.

We walked through Chinatown, on our way to our favorite Vietnamese Pho Noodle restaurant, the hole in the wall Gold Star facing onto near the little square of park over the parking garage in front of the old Chinatown Holiday Inn. What makes the Gold Star great is that if you order Pho Ga (Pho with Chicken), the chicken is a broiled leg on the side, not a bunch of characterless white squares in the broth.

This is, like, my Nth picture of Chinatown. I always like the fire escapes and the brick walls and the people walking around.

Another Chinatown fire escape. I love the colors here, and the stripes of shadow and light. The world really is so remarkably intricate and beautiful.

Here's a simpler abstract pattern, maybe in Chinatown, maybe in Santa Cruz. For going on fifty years, I've been into taking pictures that fall into an assemblage of rectangular patterns. Finding the composition is always fun, and if you have good colors that's nice. Though faint pastels are good too, or you can play off the textures.

Sometimes I worry that I've taken pictures of everything I'd ever want to take a picture of, but if I carry my camera around, I'll see stuff, even though it's, in a way, the same old stuff as ever.

Like swirls of grass or cactus. These are in the Bezerkistan (excuse me, Berkeley) Botanical Garden, just up the hill from the football stadium that they're refurbishing. A steep $7 to get in, but really a lovely place.

Cactuses, too. My god, how many cactus pictures have I taken? This is a nice cactus though. I like the little "ears" on the lower lop-lop lobe.

Back in SF, there's a little park near Mason St. and California St., in front of the big Episcopal cathedral, I often walk up there when I have some spare time. Nice breeze up there, and they have a lovely Italianate fountain, complete with bronze turtles.

Good water coming off the fountain, too. Water's another thing I've photographed a zillion times. Sometimes I feel like I ought start shoving my lens into people's faces on the streets, or telephotoing them—and now and then I do that a little—sometimes I try and work to have a personality for street photography, but of course a lot of time, I don't want to work.

Well, here's one piece of light street photography, a mover in a van in Santa Cruz, you can't see his face, and he really does fill out the picture. Just that dolly isn't enough—I shot the picture first that way, and then with the guy in it, and with the guy it's much fuller.

So now I'm back into The Turing Chronicles. Around the corner and into the home stretch. Not to overdramatize, but I feel like a primitive hunter in the woods.

I've been on the trail of this great beast for years, he's wounded now, I can see more and more of his blood on the leaves, I can hear him in the underbrush up ahead, I'm pushing forward, heedless of the branches scratching my face, my whole being is focused on the task of taking down the beast at last, I want to bring him to the ground and tear out his throat to see him shudder and lie still, finishing this long quest at last.

And do understand that this is metaphorical, in reality I've never hunted and, generally speaking, I even go out of my way to avoid killing insects. But a novel you've been actively working on for a year—and planning for five years—that's a beast you want to lay to rest.

June 22, 2011

Plans For The V-Bomb

I finished my painting of my friend Vernon Head near Mt. Umunhum and the Guadalupe Reservoir south of San Jose last week. I used a palette brush more than usual. Vernon's a good painter, you can see some of his oils here.

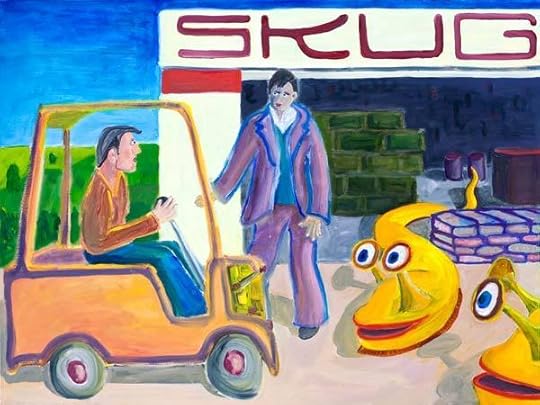

I want to get back into my novel The Turing Chronicles now, but I'm still painting, a piece called V-Bomb. I think the painting is helping me with the novel.

The V-bomb is a device that Alan Turing is going to use perhaps to remove these parasitic skug creatures from Earth—or perhaps to spread skugs all over Earth. We'll suppose that the V-bomb rays are expected to pass through matter, so there's no particular need to set it off high up in the atmosphere. It's just sitting in a tin shed in the Frijoles Canyon near Los Alamos. Like this:

I found another big stash of bomb photos online, including this one of the of the Trinity bomb, shown above, with gnarly exposed wiring. It was built in Los Alamos, they called it The Gadget, and it exploded in the first nuclear weapons test of an atomic bomb, which took place on July 16, 1945, near White Sands, New Mexico.

That cross-legged guy suggests the idea of Turing getting inside the V-bomb. And instead of expanding outwards, the V-bomb implodes. I got the imploding idea from my painting V-Bomb that I'm currently working on. I kind of ruined the painting today…a lot. The colors are horrible. But I did get the layout the way I wanted.

It's just a stage. Version 2. And now on to Version 3. I've recently developed this habit of photographing my painting in its current state, and then collaging or drawing in extra bits in Photoshop, and using that as a mockup for the next stage. So here's the mockup for Version 3.

The win for me in this process is that sometimes working on a painting can give me an idea for a piece of fiction I'm working on.

My idea in the mockup above is that Turing is squatting in the V-bomb on the right, and then he's vaporized and becomes the living essence of the blast—which is shrinking towards a tiny size—and then, when the blast is sufficiently compact, a rip opens up in the fabric of space, and Turing slides through into the afterlife.

"Turing and the Skugs", 40″ x 30″ inches, Oct 2010, Oil on canvas." Click for larger version.

Note, however, that he'll need to send out some rays—or perhaps some logic paradox?—to destroy any free-ranging skugs, and to restore any skuggers to their normal state.

June 20, 2011

My Oddest Fan Letter

Looking through my image files the other day, I unearthed my oddest fan letter ever—and, believe me, there's been some stiff competition over the years.

Click on the image to see a larger image.

This arrived in 1981, shortly after my first published novel , White Light. I'd crafted a subtle tale about the 1960s, higher infinities, and the afterlife. And having read my book in a prison library, some guy smeared ink on his foot, stomped on a piece of paper, and sent me the results. In his mind we were literary peers—and I should collaborate on a book with him.

A book about the wrinkle on his foot.

June 19, 2011

Fathers Day. Stan Ulam.

First a word about Father's Day. I'm lucky enough to have children and to have known my father. It's wonderful to think about the generations rolling on.

I hope all fathers and sons get some nice hammock time today or a reasonable equivalent thereof. Slack.

When my father died, he had very few possessions. I "inherited" four or five things of his, including a worn cardigan sweater, a Swiss knife, and an egg-cup that one of my daughters had made for him.

Thinking about the "rolling onward" and "eternal recurrence" aspects of being a son or a father, I took a picture of Pop's eggcup with a little can of Royal Baking Powder that happens to be in the Spanish language. The cool thing about the Royal label, well known to mathematicians and cartoonists, is that it incorporates an endless regress.

I think I got hold of this can about 25 years ago, soon after moving to CA, when I was still surprised to see Spanish, and I (with deliberate incongruity) used the name "Polvo Para Hornear" for the name of a landmark in my novel The Hacker And The Ants.

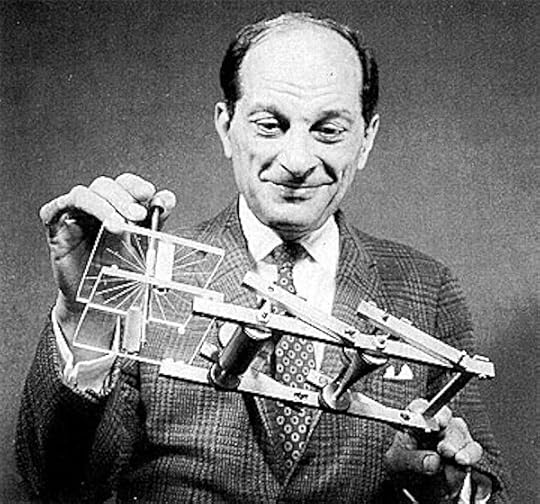

Switching topics now, I've been doing research on Stanislaw Ulam this week. He's going to appear as a character in my novel The Turing Chronicles. I like this photo of Ulam happy with some device he's cobbled together perhaps to model some arcane physical concept like the notion of a nonlinear springs he discussed in his classic "Fermi-Pasta-Ulam" paper, FPU for short.

For more on this topic, see the software and papers on my Capow page, where I used continuous-valued cellular automata software to run the FPU simulation, reproducing some of Ulam's results, such as the ergodic long-term reoccurrence of states for the cubic nonlinear CA.

I found a very interesting essay (although somewhat eccentric and possibly unfairly critical or eve hostile) essay by his mathematician friend (?) Gian-Carlo Rota: The Lost Cafe.

Summary: Rota says Ulam was lazy, didn't like to work out the details, preferred the flash of insight. He was as sort of alienated and sarcastic, didn't like authority, felt that ultimately everything was meaningless. Undisciplined. Generous and kind. Liked getting into new fields and picking off the interesting big results. Often didn't get around to publishing his results, just shared them informally. He had green eyes.

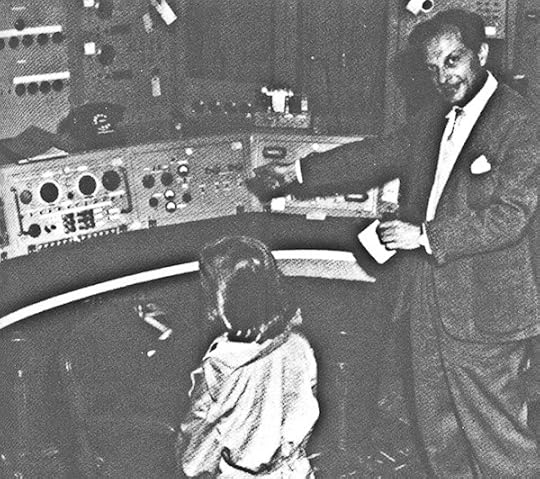

Classic photo of Ulam and the MANIAC computer with his daughter Claire. I first saw this photo in Ulam's autobiography, Adventures of a Mathematician. I wrote LANL and got permission to use it as an illo in my Lifebox tome.

Ulam is known for his work on the H-bomb, indeed he's sometimes called the father of the H-bomb. Ulam and Edward Teller made a joint application for a patent on the H-bomb!

In wondering if Ulam was "evil" for helping to invent the H-bomb, keep in mind that he was from a Jewish family in Lwow, Poland, and that he and his brother happened to escape to the US in 1938. The rest of his family died in the holocaust. Perhaps this motivated him to help the military of his new home country.

Another factor in Ulam's work here was that of scientific obsession. Ulam didn't get along with Edward Teller, and he developed his design for the H-bomb partly in a desire to demonstrate the Teller's original design for such a weapon was wrong. Teller then jumped on Ulam's design and worked on it some more.

Photo of an A-bomb fireball, from a photo-rich Russian site. Note the Joshua trees about to be consumed. I'm intrigued by the irregular spots on the fireball. No natural phenomenon is ever completely uniform.

June 15, 2011

Drifting Point of View

Today's post drifts through several topics.

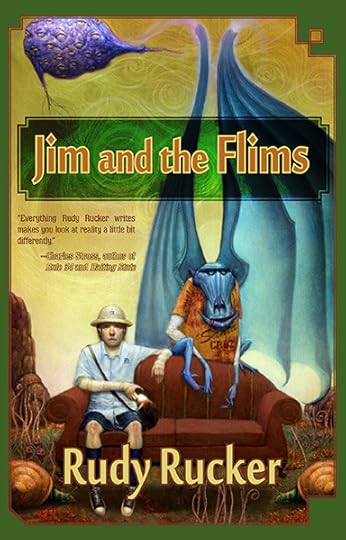

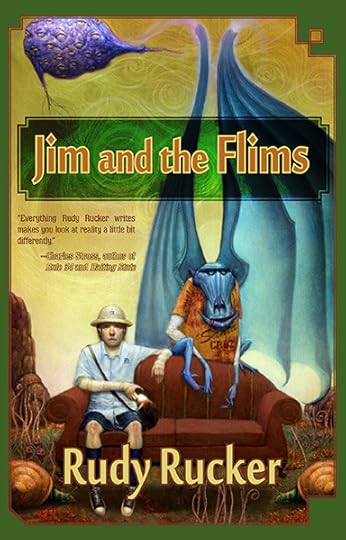

My new book Jim and the Flims got a nice review on the webzine Tor.com. The book's out in hardback and Kindle format now.

Our daughter Georgia was out here last month. We spent one afternoon painting together, dressed in in my hobo-like no-worries-about-smudges painting clothes. I was working on a picture of a landscape with my painter friend Vernon, and Georgia was working on a picture of me painting the picture of Vernon. A regress! (I'll post the picture of Vernon next week.)

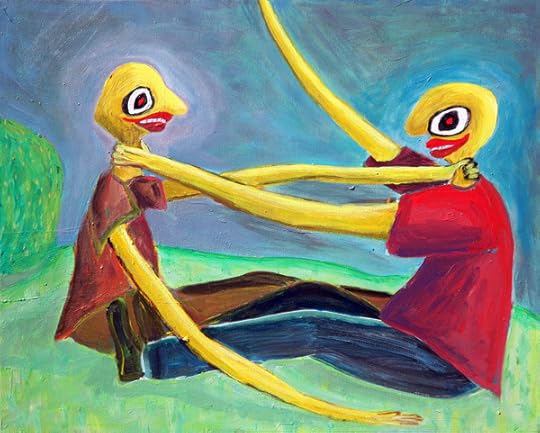

I also started a new abstract that looks kind of like two olives. This is only a snapshot of a preliminary draft.

The thing with abstracts is that usually right at the beginning after only a little bit of work, the picture looks really great. But I don't want to stop then, I want to have more painting fun. So then I ruin the picture. And then I spend the next few weeks trying to fix it. This is in fact a kind of typical process in painting: A beautiful start, you ruin it, and from then on you're trying to fix it…and once it's okay, maybe you ruin it again, and paint some more.

I very rarely abandon a picture and just scrape it off. I think it's kind of nice to have the layers accumulate and to keep adding more. Throwing good paint after bad. My new goal, suggested by Paul Mavrides, is to try and build up a thicker texture on my canvases. Let me remind any newcomers that my painting are for sale, either as originals or prints. Sell it, Ru.

I wrote a story, "To See Infinity Bare," with my pal Paul DiFilippo in August, 2008. It was in some measure inspired by the image in the film Amadeus of the great Mozart being buried in a sheet in a public grave. And by James Blish's cool 1954 story, "Beep." The vicissitudes of publishing are such that "To See Infinity Bare" has appeared only now, three years later. In any case it's in a very nice anthology, Postscripts #24/#25 from the redoubtable PS Publishing.

The other day I saw my writer friend Karen Fowler, and she remarked that T. C. Boyle's 2003 Drop City was perhaps the best 1960s book she'd read.

So I finally got around to reading Drop City myself. Boyle has a beautiful style, and the characters are nicely developed (if maybe a little too clearly good guys or bad guys). But it was a total page-turner, I hadn't read a book like that for quite awhile. The plot was nicely woven, like macramé you might say. I like when I have a book like that, as then I don't have to worry about what to do with my spare time—I just lie on the couch and read more!

Boyle's hippie characters are very much like the characters in Thomas Wolfe's 1968 The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Maybe there's only one way to write those characters.

The only thing I didn't quite like about the book was the number of violent scenes. These Hollywood-type fist-fights with one guy's arm raising and lowering like a piston as he repeatedly slugs his felled enemy in the face. In reality I've never seen a fight like that in my whole life, and Drop City has probably a dozen. People really don't do that kind of thing very often, and those passages are kind of dull, like porno or dream journals.

But other than those very few pages, it's a wonderful book, and it really does bring back the past for this old hippie.

I'm nearing the home stretch on my work in progress, The Turing Chronicles. I'm about to write a double-length chapter called "Nonlinear Feedback."

Up till now I'd planned for two separate chapters here, but then I got the idea that it would be richer if could shuffle two chapters together.

The chapter title "Nonlinear Feedback" expresses the kind of flow I'd like to see. One weird kick after another, each kick jolting the next one to a higher level than anticipated. Each kick adding nonlinear feedback.

Given that I have two chaps worth of material, it's a little hard to wrestle it into shape in my outline. For awhile I had a structural idea of using a kaleidoscopic approach and structuring the chapter as a series of short pops, with each POP from a different point of view.

When I say "pop," I'm thinking of a string of firecrackers going off.

So I wrote out a list of pops a few days ago and printed out the list and cut them apart with scissors and shuffled them by hand, Burroughs-cut-up style, and that made me excited.

And then I rearranged my electronic text to match the pasted-up cut-up, and it wasn't quite right, so I did, like, four more rewrites of the chapter outline, and in the process I smoothed away the potentially jarring section breaks.

And then I got into clarifying the chapter's timeline, nailing down the date and time for each event, to help master the flow. With a complex chapter like this, it's all about finding a way to control the material. Thinking in terms of point of view and of timeline are two different ways to chunk the material at a higher level.

Regarding point of view, I will in fact switch points of view repeatedly during the chapter, but I'll be using the risky "drifting point of view" favored by Philip K. Dick (and by amateur writers). I'll be using a third-person narration, but getting close-in on the current viewer, kind of looking through their eyes. It is possible to make the drifting POV work, but it's tricky. Ordinarily I prefer having like "***"-type section breaks to signal the shifts. But doing the drift sets me a new challenge and that keeps the game interesting.

The carrot drawing me on is that pretty soon I get to send Alan Turing into a really huge bomb explosion. The V-bomb which may or may not generate a ray to turn everyone in the U.S.A. into a skugger! Did I mention that The Turing Chronicles is a 1950s Invasion Story?

June 10, 2011

Death vs. Immortality

I'd like to thank Emilio, Steve H, Rick York, and Justin, for their kind and encouraging comments on my previous post, "My Brain Event as a Jump-Cut."

There's nothing like a good bull-session about death and immortality! I'll fuel the discussion with a few further remarks sparked by the comments.

(1) It will never be absolutely certain that death really is the end. There's so much that we don't know about the universe. But, given my personal experiences, my inclination these days is to go ahead and accept that death is the end, and see where that leads me. It's worth mentioning that, throughout history, people have often used the promise of immortality as way to take advantage of their followers. Perhaps it's just as well to accept the very high probability of total dissolution and find ways to get past the fear.

A related point. It's very healthy and reasonable to fear and to avoid death—that's what gets us through our lives! But we might learn to take a different view of the final and unavoidable encounter with the Reaper.

(2) It's correct that it's not accurate to use "black" to refer to the experience of total lack of consciousness. That's just a conventional term for "no visual input". But if there's no "eye" and no brain, it isn't even black. It's void.

It's also true that the void is what precedes my birth. (Unless I want to claim that my soul is reincarnated, and that between incarnations I hang out in the Heavenly Clouds, and when, eventually, I get overly interested in watching a man and woman having sex, I get pulled back into the material plane, down into a fertilized egg.)

I would say that the unconsciousness you experience during total anesthesia or as the effects of a brain event does have a different quality from the unconsciousness felt during sleep. There are no dreams and, upon awaking, no sense of an intervening passage of time. Thus my use of the phrase "jump-cut".

I think it's a unpleasant sensation at two levels. First of all, we like to feel that, at any time, we're at some level monitoring our body and keeping it save. Secondly, the experience (or non-experience) of a total mental void is, as I've been saying, a stark preview of death.

(3) There are various partial forms of immortality that we comfort ourselves with, such as genetic immortality or software immortality. On the genetic front, we might, if we're lucky, leave some children behind, bearing our genetic info and some of our memories. On the software front, you might make an impression on people, perhaps as an educator or a social worker. Another form of software immorality is to leave books, recordings or works of art.

These forms of pseudoimmortality mean something to us, even if actual death truly is a matter of lights-out and that's all she wrote. When you're younger you're often concerned about living long enough to do things you feel you need to do—you want to taste the pleasures of life, and it may be that you also want to set up some pseudoimmortality of the genetic or software forms.

I still remember my terror, as a teen, at the prospect that I might die a virgin. If you're fortunate, you live long enough to check off most of the things on your list. And at this point death begins to lose some of its sting.

(4) The SF notion of creating a replica of oneself, as in my 1982 novel Software, is a perennial favorite, popular these days among Singulatarians and Transhumanists.

Perhaps you save off your brain software and copy it over to a healthy young clone, for instance. Or perhaps, at some later time, as Steve H suggests, some future biohackers do this for you, creating an emulation of your brain software based on whatever lifebox type data you left behind. ("The blog is the road to immortality!")

I've always been intrigued by the existential questions that arise here. Even if I manage to create a new Rudy, my old self still enters the void. My new self may have the illusion of being a continuous extension of my old self, but nonetheless, my old self—(and what does that really mean?)—is annihilated. I delve into this in more detail in my non-fiction books Infinity and the Mind and The Lifebox, the Seashell and the Soul.

June 6, 2011

My Brain Event as a Jump-Cut

I haven't directly blogged about this topic before, but on July 1, 2008, right after I finished the final draft of my novel Hylozoic, I had a hemorrhagic stroke. This meant that a blood vessel in the right half of my brain had suddenly burst. The fact that it was prone to bursting was in the nature of a birth defect, a booby-trap that had been waiting for 62 years. I kind of prefer the euphemism "brain event" for it.

Fortunately I didn't suffer any really dire consequences like paralysis or speech-slurring. For me, the most disturbing thing about the experience was in some sense philosophical. When I awoke in the hospital, I had no sense at all of any intervening time period. And that still bothers me. The interval when I'd been unconscious was like a jump-cut. Bam. And it seemed fairly clear that it would have been entirely possible to never wake up at all.

A couple of months afterwards, on September 12, 2008, I made a painting called, "Cerebral Hemorrhage." I wasn't quite that bad off, but it almost felt that way. I like the 3D blob of blood and its shadow on the sheet, also the way the guy's soul is flowing out through the soles of his feet…with the lobes of his brain piled up on the right like a compost heap, with a terrified, watchful eye on top, twinned with the eye in that starfish-shaped soul.

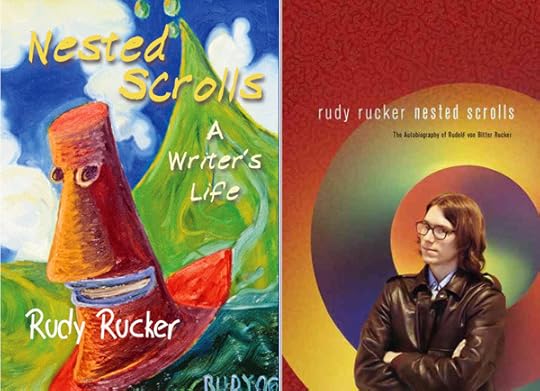

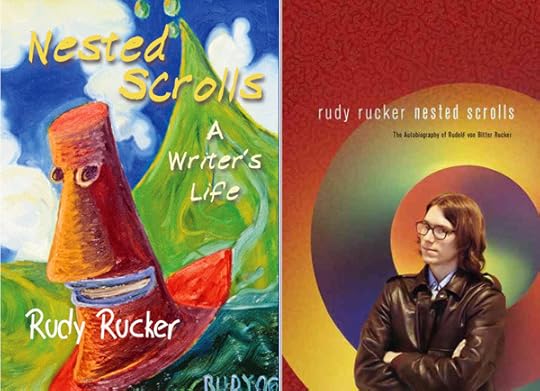

And I started writing about the stroke that fall in what turned into two books. The first is my autobiography, Nested Scrolls, which starts out with the stroke.

Conditioned by a zillion novels and movies, you tend to think of death as a big drama—with a caped Grim Reaper kicking in your midnight door. But death may be as ordinary as an autumn leaf dropping from a tree. No spiral tunnel, no white light, no welcome from the departed ones. Maybe it's just that everything goes black.

In those first mornings at the hospital, I'd sit on their patio with an intravenous drip on a little rolling stand, and I'd look at the clouds in the sky. They drifted along, changing shapes, with the golden sunlight on them. The leaves of a potted palm tree rocked chaotically in the gentle airs, the fronds clearly outlined against the marbled blue and white heavens. Somehow I was surprised that the world was still doing gnarly stuff without any active input from me.

As I slowly recuperated in July and August of 2008, I started writing in my journal, and then in a Notes document. At that point I wasn't yet sure whether I was planning to write a memoir or a novel.

One the one hand, my brush with death had made it very clear that, if I was ever going to write an autobiography, the time was now.

On the other hand, my trains of thought were running very loopy, and it seemed like it might be entertaining to use the stroke as an event in a transreal novel, possibly a novel involving the afterworld.

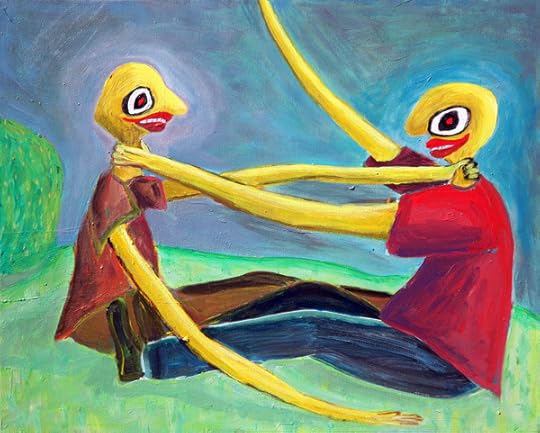

I actually did a painting before "Cerebral Hemorrhage." This one, finished July 21, 2008, is called "Collaborators." I went out to some en plein air painting with my friend Vernon. We were bickering a little about whether or not I'd picked a good spot.

I started out with an image of two painters, and then I had them start choking each other. As I really don't have any strong hard feelings towards Vernon, I'd say that what I was really depicting is the stroke itself as an external being attacking me. Choking me around the neck. It's not so uncommon in dreams, or in adventure movies, to have a hero and his demon/double get into a choking contest.

But then I remembered that right before my stroke I'd just finished a rather bruising round of revisions on a story I was co-writing with Bruce Sterling—our fifth short story, "Colliding Branes," which appeared in Asimov's in 2009. So it oddly amused me to tell Bruce, who I love, that my attack of "apoplexy" was his fault for being so intransigent and argumentative. He'd pushed me over the edge. He'd nearly killed me. Not falling for the guilt trip, Bruce imperturbably replied that I wouldn't have any further problems if I would just accept that he was always right. Actually, our sixth collaboration, "Good Night Moon", in 2010, went much smoother. I'd accepted that Bruce was often (if not always) right.

One of the things bothering me was that I wasn't feeling as if I had an eternal soul. As I wrote in my journals on July, 20, 2008.

I have a new sense of seeing the street scene without "me" at the center. I used to see the world as if it had a big reflecting ball in the middle, the ball being me and my feelings. But this week it feels like the ball is gone. I'm just seeing a lawn with people. I'm not there at all, or I'm much smaller than before. It's like there's a hole in the scene.

I express a related idea in Nested Scrolls.

I think this was when I finally came to accept that the world would indeed continue after I die. Self-centered as I am, this simple fact had always struck me as paradoxical. But now I understood it, right down in my deepest core. The secrets of the life and death are commonplace, yet only rarely can we hear them.

As you can see from a blog post of mine, "Teeming Tales," by August 4, 2008, I'd pretty much decided to write a novel in parallel to my memoir. Although I had less reason than ever to believe in an actual afterworld, but this only meant that I had more of a reason than ever to fantasize about life after death. Fantasy and science-fiction novels are, after all, to a large degree instruments for authorial wish-fulfillment. You write about the kinds of worlds that you wished you lived in. And I wished more than ever that I lived in a world where there was an afterworld—call it Flimsy.

Some of the stroke material ended up in my novel Jim and the Flims.

I vegged out on my dusty Goodwill couch, reading a paperback fantasy novel. It was a peaceful summer afternoon, with the sunlight lying across the roof and yard like heavy velvet.

After awhile I began having the feeling that I could read the pages of the book without actually looking at them. But I was having trouble making sense of what I read. Thinking I needed a nap, I laid down my book and curled up on my side. I dropped off to sleep.

The next thing I knew, I was lying on the living room floor, very confused. It was dark outside. I felt like I'd been—gone. I ached all over, in every muscle and joint. My tongue was bleeding. Something very bad was happening to me.

I crawled across the room to where my cell phone sat with my keys. I didn't trust myself to walk. It took all my concentration to dial 911. And then everything went black again.

I awoke in a hospital room. It was still night. A nurse was standing over me, a woman with a calm, sympathetic face. She said I'd had two seizures. They weren't sure why. Maybe I'd be okay. They had me on an IV drip with painkillers and an anti-seizure drug. I needed to rest.

I slept fitfully. In the morning I was able to think a little. I could hardly believe I was in the hospital. How disturbing to think that I'd been to death's door and back. I hadn't seen any white light or spiral tunnel or dead relatives while I'd been out—none of that cool, trippy stuff. I'd been nowhere and I'd seen nothing. It just felt like I'd had a couple of time-sequences snipped out of my life. Discouraging.

Two final remarks. First of all, I'm happy to report that I'd made a full recovery from that July 1, 2008, brain hemorrhage by the fall of 2008. I got off easy. I went back to life as usual—writing books, going on trips with my wife, making visits with the kids, writing blog posts. Regular life is such a sweet and wonderful thing.

A second point. It feels like ever since I had my brain hemorrhage, people have been telling me to watch Jill Bolte Taylor's TED video talk "A Stroke of Insight". So today I finally did.

And it's really a lovely talk. She's a great speaker, very emotional, funny at times, and with an uplifting message: stay in touch with your non-linear, mystical right brain. The way she gets from the stroke to the message is that the blood vessel that burst in her brain happened to be in the logical, left hemisphere. And it didn't immediately knock her out. So she had a few minutes more or less like an acid trip, in which she was seeing the world through the right brain.

In my case, the blood vessel burst in the right half of my brain, and I almost immediately blacked out. For me it wasn't like like an acid trip, it was a jump cut. Bam, everything black, then you're awake. And at some point, Jill hit the jump-cut, too, although she doesn't talk about it very much. It's sort of negative and disturbing thing. And people don't really want to think about that. They want to push that aside and think about the insight and the high. Let them.

I'm all for living in my right brain and being in touch with the cosmos at large. I was just now outside in our garden watching the fat bumblebees on our salvia flowers. Right-brain joy.

But I'm living in the fairly sure and certain knowledge that at some moment in my future, it's all going to stop. Bam. And I more or less have to be okay with that. If I worry about it, the fear poisons my life. If I accept it, I can enjoy what I have left. More flowers, food, family, and writing. It's good while it lasts. For that matter, it's a miracle and a blessing that we get any life at all.

My Stroke as a Jump-Cut

I haven't directly blogged about this topic before, but on July 1, 2008, right after I finished the final draft of my novel Hylozoic, I had a hemorrhagic stroke. This means that a blood vessel in the right half of my brain had suddenly burst. The fact that it was prone to bursting was in the nature of a birth defect, a booby-trap that had been waiting for 62 years.

The most disturbing thing about the experience was that, when I awoke in the hospital, I had no sense at all of any intervening time period. The interval when I'd been unconscious was like a jump-cut. Bam. And it seemed fairly clear that it would have been entirely possible to never wake up at all.

A couple of months afterwards, on September 12, 2008, I made a painting called, "Cerebral Hemorrhage." I wasn't quite that bad off, but it almost felt that way. I like the 3D blob of blood and its shadow on the sheet, also the way the guy's soul is flowing out through the soles of his feet…with the lobes of his brain piled up on the right like a compost heap, with a terrified, watchful eye on top, twinned with the eye in that starfish-shaped soul.

And I started writing about the stroke that fall in what turned into two books. The first is my autobiography, Nested Scrolls, which starts out with the stroke.

Conditioned by a zillion novels and movies, you tend to think of death as a big drama—with a caped Grim Reaper kicking in your midnight door. But death may be as ordinary as an autumn leaf dropping from a tree. No spiral tunnel, no white light, no welcome from the departed ones. Maybe it's just that everything goes black.

In those first mornings at the hospital, I'd sit on their patio with an intravenous drip on a little rolling stand, and I'd look at the clouds in the sky. They drifted along, changing shapes, with the golden sunlight on them. The leaves of a potted palm tree rocked chaotically in the gentle airs, the fronds clearly outlined against the marbled blue and white heavens. Somehow I was surprised that the world was still doing gnarly stuff without any active input from me.

As I slowly recuperated in July and August of 2008, I started writing in my journal, and then in a Notes document. At that point I wasn't yet sure whether I was planning to write a memoir or a novel.

One the one hand, my brush with death had made it very clear that, if I was ever going to write an autobiography, the time was now.

On the other hand, my trains of thought were running very loopy, and it seemed like it might be entertaining to use the stroke as an event in a transreal novel, possibly a novel involving the afterworld.

I actually did a painting before "Cerebral Hemorrhage." This one, finished July 21, 2008, is called "Collaborators." I went out to some en plein air painting with my friend Vernon. We were bickering a little about whether or not I'd picked a good spot.

I started out with an image of two painters, and then I had them start choking each other. As I really don't have any strong hard feelings towards Vernon, I'd say that what I was really depicting is the stroke itself as an external being attacking me. Choking me around the neck. It's not so uncommon in dreams, or in adventure movies, to have a hero and his demon/double get into a choking contest.

But then I remembered that right before my stroke I'd just finished a rather bruising round of revisions on a story I was co-writing with Bruce Sterling—our fifth short story, "Colliding Branes." So it oddly amused me to tell Bruce that my attack of "apoplexy" was his fault for being so intransigent and argumentative. He'd pushed me over the edge. He'd nearly killed me. Not falling for the guilt trip, Bruce imperturbably replied that I wouldn't have any further problems if I would just accept that he was always right.

One of the things bothering me was that I wasn't feeling as if I had an eternal soul. As I wrote in my journals on July, 20, 2008.

I have a new sense of seeing the street scene without "me" at the center. I used to see the world as if it had a big reflecting ball in the middle, the ball being me and my feelings. But this week it feels like the ball is gone. I'm just seeing a lawn with people. I'm not there at all, or I'm much smaller than before. It's like there's a hole in the scene.

I express a related idea in Nested Scrolls.

I think this was when I finally came to accept that the world would indeed continue after I die. Self-centered as I am, this simple fact had always struck me as paradoxical. But now I understood it, right down in my deepest core. The secrets of the life and death are commonplace, yet only rarely can we hear them.

As you can see from a blog post of mine, "Teeming Tales," by August 4, 2008, I'd pretty much decided to write a novel in parallel to my memoir. Although I had less reason than ever to believe in an actual afterworld, but this only meant that I had more of a reason than ever to fantasize about life after death. Fantasy and science-fiction novels are, after all, to a large degree instruments for authorial wish-fulfillment. You write about the kinds of worlds that you wished you lived in. And I wished more than ever that I lived in a world where there was an afterworld—call it Flimsy.

Some of the stroke material ended up in my novel Jim and the Flims.

I vegged out on my dusty Goodwill couch, reading a paperback fantasy novel. It was a peaceful summer afternoon, with the sunlight lying across the roof and yard like heavy velvet.

After awhile I began having the feeling that I could read the pages of the book without actually looking at them. But I was having trouble making sense of what I read. Thinking I needed a nap, I laid down my book and curled up on my side. I dropped off to sleep.

The next thing I knew, I was lying on the living room floor, very confused. It was dark outside. I felt like I'd been—gone. I ached all over, in every muscle and joint. My tongue was bleeding. Something very bad was happening to me.

I crawled across the room to where my cell phone sat with my keys. I didn't trust myself to walk. It took all my concentration to dial 911. And then everything went black again.

I awoke in a hospital room. It was still night. A nurse was standing over me, a woman with a calm, sympathetic face. She said I'd had two seizures. They weren't sure why. Maybe I'd be okay. They had me on an IV drip with painkillers and an anti-seizure drug. I needed to rest.

I slept fitfully. In the morning I was able to think a little. I could hardly believe I was in the hospital. How disturbing to think that I'd been to death's door and back. I hadn't seen any white light or spiral tunnel or dead relatives while I'd been out—none of that cool, trippy stuff. I'd been nowhere and I'd seen nothing. It just felt like I'd had a couple of time-sequences snipped out of my life. Discouraging.

Two final remarks. First of all, I'm happy to report that I'd made a full recovery from that July 1, 2008, brain hemorrhage by the fall of 2008. I got off easy. I went back to life as usual—writing books, going on trips with my wife, making visits with the kids, writing blog posts. Regular life is such a sweet and wonderful thing.

A second point. It feels like ever since I had my brain hemorrhage, people have been telling me to watch Jill Bolte Taylor's TED video talk "A Stroke of Insight". So today I finally did.

And it's really a lovely talk. She's a great speaker, very emotional, funny at times, and with an uplifting message: stay in touch with your non-linear, mystical right brain. The way she gets from the stroke to the message is that the blood vessel that burst in her brain happened to be in the logical, left hemisphere. And it didn't immediately knock her out. So she had a few minutes more or less like an acid trip, in which she was seeing the world through the right brain.

In my case, the blood vessel burst in the right half of my brain, and I almost immediately blacked out. For me it wasn't like like an acid trip, it was a jump cut. Bam, everything black, then you're awake. And at some point, Jill hit the jump-cut, too, although she doesn't talk about it very much. It's sort of negative and disturbing thing. And people don't really want to think about that. They want to push that aside and think about the insight and the high. Let them.

I'm all for living in my right brain and being in touch with the cosmos at large. I was just now outside in our garden watching the fat bumblebees on our salvia flowers. Right-brain joy.

But I'm living in the fairly sure and certain knowledge that at some moment in my future, it's all going to stop. Bam. And I more or less have to be okay with that. If I worry about it, the fear poisons my life. If I accept it, I can enjoy what I have left. More flowers, food, family, and writing. It's good while it lasts. For that matter, it's a miracle and a blessing that we get any life at all.

June 3, 2011

JIM AND THE FLIMS in Capitola/Santa Cruz Saturday Night.

Jim and the Flims, my fantastic novel of Santa Cruz and the afterworld has appeared from Night Shade Books. See my JIM AND THE FLIMS page for more info.

I'll be giving a reading from Jim and the Flims at the Capitola Book Café on June 4, at 6:30 pm, sharing the podium with Kim Stanley Robinson, who'll read from Galileo's Dream, with Rick Kleffel moderating a discussion.

Rudy Rucker's Blog

- Rudy Rucker's profile

- 583 followers