Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 52

February 24, 2011

Speakage

On Friday, February 26, at 4:45 pm, I'll speak for a half hour on "Lifebox Immortality" at the Personal Archiving conference in San Francisco.

For background on my lifebox idea—and a crude implementation—see my recent post on "Digital Immortality Again."

[A skyline in San Sebastian, Spain]

Rick Kleffel made a nice podcast of a reading I did of "The Birth of Transrealism," a chapter from my forthcoming memoir, Nested Scrolls: A Writer's Life, back on January 15, 2011, in San Francisco at the SF in SF gathering. Here's his post about the podcast on his blog, "The Agony Column." You can also get to the podcast via my Feedburner podcast station, click the icon below.

A videotape of my Garum Day talk in Bilbao is now online as well.

You can find my description of this talk in my recent post, "Selling Yourself". It relates to the lifebox theme as well.

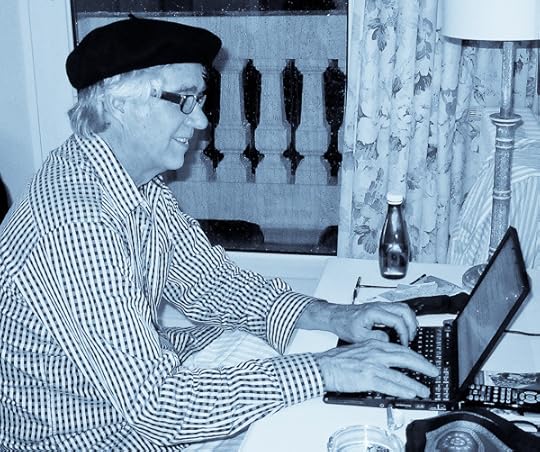

Maybe for my talk in SF tomorrow, I'll wear my new *eeek* Basque beret.

February 23, 2011

Spanish Basque Country: Bilbao

My wife Sylvia and I just spent a week in Basque country in the north of Spain, in the towns of Bilbao and San Sebastian. I was there to give a talk for "Garum Day" as mentioned in a previous post. For today's post I'll run about half of my pictures, with comments. A few of the pictures are by Sylvia, mostly the ones of me.

Our hotel, the Domine, was right across from the famous Gehry-designed Guggenheim museum in Bilbao. Jeff Koons's Puppy stands right outside the museum. Some people find this work annoying, but I think it's cool, a definite heir to the work of Warhol. "Puppy" has quite a presence in person. The locals seem to like it, and the flowers (pansies) get replaced three times a year. There's a certain camouflage-pattern quality to how the patches of flower colors are arranged—more thought went into the work than one might think.

So here I am with the museum itself, the metal skin is titanium, it's awesome. No one picture really captures the thing.

When we got to Bilbao we were jetlagged, and slept till it was dark, and then we walked around the Guggenheim at night. In the back, the buttresses seem like castle ramparts.

There's a nice old-town section of Bilbao too, of course, including a church that was at one time part of the city wall. A great rose window in the ceiling of one alcove.

This guy was playing great Spanish-style guitar in the street by the cathedral. And dig the woman hurrying by with her cell phone.

One of our big projects in Bilbao and San Sebastian was seeking out good tapas bars. They call tapas pintxos there, that's the Basque word for these little canapé-like snacks that are piled on platters in many of the bars. The "tx" is pronounced "tsch". The place in this photo is the Café-Bar Bilbao, in Plaza Nueva, a really pleasant square. They had good tapas in this place, and I loved the tiles on the walls. But, as any local will tell you the really great tapas is in San Sebastian.

A tricky thing about going out for meals in Spain is the restaurants and cafes mainly serve lunch from 2 to 4 in the afternoon and dinner from 9 to 11 at night. Seriously. Many restaurants aren't even open before 9 in the evening. It's a whole different rhythm, but with our jetlag it was a pretty good fit. The thing is, you kind of just do your sedentary evening activities (like lying around reading or cruising the web) before supper.

Bilbao has a little historical and archeological Museo Vasco (Vasco=Basque) museum with an ancient (maybe 200 BC) statue of a pig (or maybe it's a bull…the locals call it the pig-bull). I couldn't get into the pig-bulls courtyard to touch him, but he was beautiful as seen through the window with his green grass and the gentle shadow of a little tree beside him.

Another picture of the Guggenheim. The upper pieces of the building—what do you call them, battlements?—blend nicely with the clouds. One of the locals claimed it rains every day in Bilbao. But the sun comes out too.

Our hotel had angled windows that reflected the colors of the Guggenheim and of a big red arch over a bridge next to the Guggenheim.

Here's the red arch at night with people walking along the river below. Gehry ran a long exhibition hall out of the museum that runs under the bridge and holds this collection of really enormous Richard Serra sculptures, a suite called "The Matter of Time."

I'd never really liked Serra's work before this trip—in the past it struck me as overbearing and blank. But it was very inspiring to be walking around inside these giant maze-like spirals with their interesting curvatures—some were spherical in the sense of curving the same way in all directions, some were "toroidal" in the sense of curving in two different directions, like a saddle. There's amazing echoes inside the Serras as well.

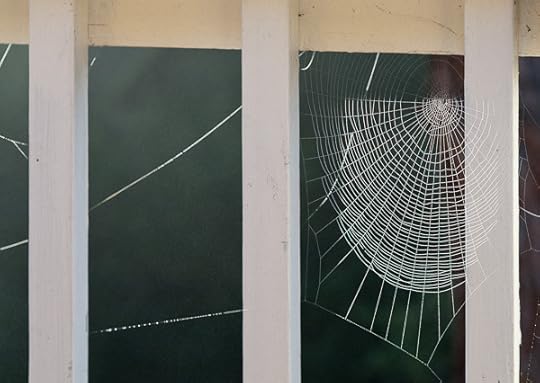

One last photo from Bilbao, and in the next post or two, I'll show pictures from San Sebastian. What's this menacing image above? It's Maman, by Louise Bourgeouis, photographed outside the Guggenheim at night. The jacked-up ISO on my Canon S90's chip turned the black sky into blue.

And this sculpture is…Mama!?! Eeek. Shades of the spider attack scene in The Incredible Shrinking Man!

February 13, 2011

My Garum Day Talk, "Selling Yourself"

(Post updated on February 23, 2011)

I was in Basque country from Feb 14 – 22, 2011, giving a talk at Garum Day on Feb 16, 2011, in Bilbao.

My talk was called (with slight irony) "Selling Yourself," and it had to do with various ways in which we try to make money by selling information, culiminating in the notion of creating software replicas of yourself—and then going on to "sell" interactions with your personality model online.

I posted a PDF of my "Selling Yourself" powerpoint slides online, and a draft of the full 'Selling Yourself" essay.

The Garum Foundation, by the way, takes their name from a type of Roman fish sauce; part of the idea is that, at their meetings, they mix together an interesting stew of ideas, another part of the idea is that a recipe for a traditional recipe is kept alive by communication and interaction.

The Garum Foundation organizer is an idealistic banker, Jose Ignacio Goirigolzarri. The conference was fun, and I had some extremely good meals.

Garum Day brought in a really big crowd, many of them were faculty or students with the Universidad de Deusto, and a number were execs for Spanish industries and banks. I took a photo of them at the end of my talk, which was more or less as outlined in the online PowerPoint and essay, although I threw in quite a bit of autobiographical material. Here's the photo of the crowd.

The audience at Garum Day, Feb 15, 2011. If you want to find yourself, click for larger version!

As of February, 23, 2011, a videotape of my talk became available online.

At the end of my talk, one person asked if I had advice for entrepreneurs in our age of the internet revolution. I didn't give a great answer at the time, but here's a three things I might have said.

(1) Chatbot or lifebox emulations of humans will be a huge online industry, see my post on "Digital Immortality Again."

(2) Any interesting online program should have a quality of unpredictability or gnarliness so as to appear lifelike and engaging. See my essay "Seek the Gnarl" or my Surrealist video, "What Is Gnarl?"

(3) Online sites are most interesting if you put a full personality into them, and have them be "transreal," that is, in some sense autobiographical, but with a layer of elaboration atop that. For some discussion of transrealism see my post "Unpredictability and Plotting a Novel." You can also listen to a podcast of my recent talk, "The Birth of Transrealism."

And, yes, my advice isn't what you'll normally hear in business school but…when has past knowledge ever been right about the future? Odd paths and new recipes are worth a try.

Another fact about Garum Day—the conference's techs and organizers were largely drawn from a cooperative group known as Las Indias, who say they were originally inspired by concepts of cyberpunk! Here's a picture of me with them.

Finally, for non-natives of Bilbao, I've placed a photo above that shows the awesome hall of Richard Serra sculptures in the Guggenheim Museum here. Serra says his suite is about time. I guess the future is at the far end…

"Selling Yourself"

I'll be in Basque country this coming week, giving a talk at Garum Day in Bilbao. My talk title is "Selling Yourself," and it has to do with various ways in which we try to make money by selling information, culiminating in the notion of creating software replicas of yourself.

I've posted a PDF of my "Selling Yourself" powerpoint slides online, and I'll post the full essay later.

The Garum Foundation, by the way, takes their name from a type of Roman fish sauce; I think the idea is that, at their meetings, we mix together an interesting stew of ideas. Should be fun, and I'm hoping for some good meals.

February 6, 2011

Early Days of Creative Programming

[ I will be speaking on some of my experiences involving software at Garum Day, an event in Bilbao, Spain, on Feburary 16, 2011. Part of my talk, and today's post, will derive from the "Computer Hacker" chapter of my memoir, Nested Scrolls: A Writer's Life, due out from PS Press in April, 2011, and Forge Books in Fall, 2011. ]

My new hacker friend John Walker was a founder and the CEO of a booming Sausalito corporation called Autodesk, and in 1988 he asked me if I'd be interested to come work for him. Autodesk had done very well with their drafting software, and they had a big surplus in the bank. Walker wanted to explore some radically new kinds of software products.

Autodesk's core business was a product called AutoCAD, an electronic drafting program used worldwide by architects and industrial designers. Walker didn't want me to work on that. Instead he was starting a small Advanced Technology Division, headed by Eric Lyons, and, for the moment, me and one or two other guys.

My first project was to produce some cellular automata software with Walker. He was an insanely talented programmer. He worked at the level of a grand master in chess, or at the level of a mathematician at the Institute for Advanced Study. Over Autodesk's one-week-long Christmas break, Walker wrote an assembly language program that eliminated any need for a special card such as the so-called cellular automaton machine I'd been carrying around.

My role in this was to create some sample CA rules for our new software to run, and to write a manual explaining it all. I got deeply into the task. Walker and I and finished our project over the course of several months. When we were done, we'd produced a slick, boxed software package called CA Lab: Rudy Rucker's Cellular Automata Laboratory, which sold for about $50 and went on the market in 1989. In those pre-Internet days, some people were actually willing to buy software of this kind on disks. I did demos of it at a number of computer trade fairs, always having to parry the same old question.

"What's it good for?"

"You stare CAs for hundreds and hundreds of hours and they eat your brain, okay?"

We sold a decent number of copies, and Walker had the idea that we could develop a whole line of software packages for hackers to enjoy. These packages were meant to be like books, but interactive, illustrating new aspects of science. Walker wanted to call the line the Autodesk Science Series.

The second package in the series was James Gleick's Chaos: The Software, designed to let users play with some of the programs mentioned in Gleick's best-selling book Chaos.

What was the chaos craze all about? Chaos is another new idea whose true origins lie in computer science. We all know about simple, deterministic processes that do something utterly predictable—like a cannonball flying along a predetermined parabola through the air. We also know about completely messy natural processes, such as the crackling static we might hear on a radio.

Chaotic processes lie midway between the extremes of predictability and randomness. On the one hand, a chaotic process doesn't settle into any kind of dull and simple pattern. On the other hand, a chaotic process isn't actually random. It's generated by some fairly simple and deterministic law of math or physics.

There's a certain overlap here with Charles Bennett's notion of logical depth . A chaotic pattern is logically deep in that it's generated by a concise rule that uses a long computation in order to produce the patterns that you see.

The hard thing to grasp about a messy-looking chaotic process is that it is in fact deterministic. If, for instance, you set about computing the successive digits of pi, you'll always end up with that same number sequence, 3.1415926… So all the digits of pi are in some sense predetermined. But yet—and this is the subtle point—the digits aren't predictable, at least not predictable by any rapidly-acting rule of thumb. Yes, someone like Bill Gosper can compute the billionth digit of pi, but he needs to run a powerful computer through quite a few cycles in order to come up with the answer. There's no quick and dirty pencil-and-a-scrap-of-paper shortcut for finding the billionth digit of pi. Pi is gnarly, pi is chaotic, pi is logically deep.

In his bestselling Chaos, Gleick talked about some mathematical systems that were known to generate chaotic patterns. Among these were the Lorenz attractor and the Mandelbrot set, and we put simulations of these into the Autodesk Chaos software, along with some other funky things.

Working on this second Autodesk program all through 1989 and 1990 was a lot harder for me than working on CA Lab had been. The big difference was that this time Walker didn't step in and write the bulk of the code. Instead I worked with another Autodesk programmer, a knowledgeable and irascible guy called Josh Gordon. Truth be told, my own programming skills were still pretty rudimentary. I was in over my head. And Josh was never shy about telling me this. But somehow we struggled to a conclusion and in 1991 we shipped this second product, too.

Later, on my own, I'd write a third science series program called Artificial Life Lab, which would be published as a disk with a book in 1993, not by Autodesk, but by the low-end Waite Group Press in the North Bay. I might mention that, annoyingly, the Waite Group refused to pay me my royalties on the Japanese edition of the book.

The three software packages that I worked on, CA Lab, Chaos, and Artificial Life Lab, are all long out of print by now, but you can download them for free from my website. Note that eventually we had to change the name of CA Lab to Cellab. A company called Computer Associates was threatening to sue us for infringing on their sacred trademarked initials CA. As if cellular automata hadn't been around much longer than them!

February 1, 2011

Alan Turing Near Las Cruces, NM

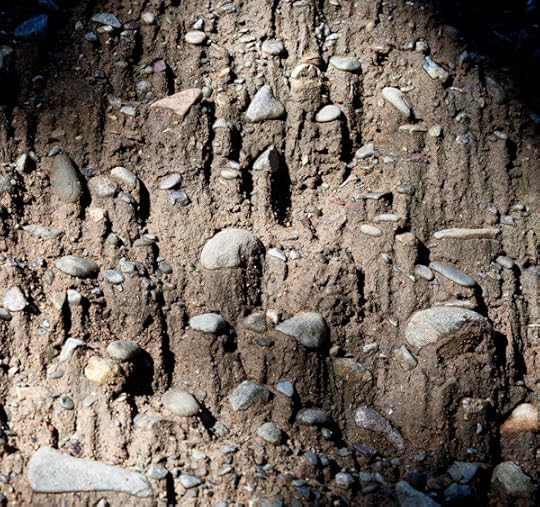

[Today, some reworked travel notes from 1999 that may make their way into my novel-in-progress The Turing Chronicles. Photos from around Los Gatos and Berkeley in the last week of January, 2011.]

Alan Turing sat on the balcony of his room near Las Cruces, New Mexico, looking at the beautiful silhouette of some low mountains across a plowed field, the range like a long jawbone with teeth in it¬—a cow or dog jawbone that one might find in the woods. A dove sat on a twisting piñon branch in the shade of the tree's main trunk, an iconic silhouette. A train not too far off was sounded its horn for the crossings in this land of trains.

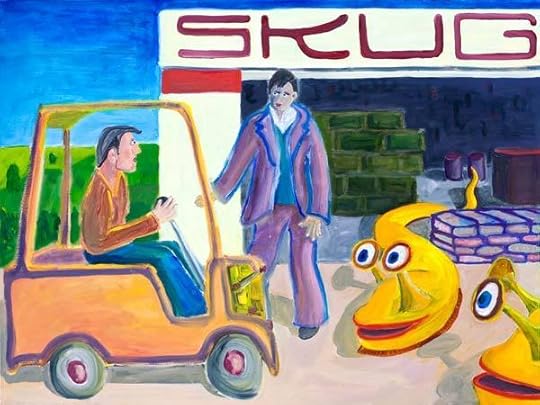

A red squirrel ram up a twisty pine tree: the squirrel fit the tree, and the two of them fit Alan's perceptions of what he should see. Everything fit. It struck him that he and the plants and animals and the skugs were all of a piece, they were all part of the same wetware world.

Before getting back on the road in the morning, Alan took a walk, admiring the clumps of prickly pear cactus, the lobbed with buds along their rims, and with yellow and red flowers sprouting amid the thorns. He liked how the cacti were so perfectly placed among the grasses and the dry red rocks. Nature's wise and lovely designs, at the fertile border between order and chaos. Little lizards lifted up their striped tails to run away.

[Detail of "Turing and the Skugs," see my paintings page for more info.]

Alan came across a hillside cemetery with a few cracked stones amid long grass and thick-trunked old cypresses, the trees not immensely tall. In the wind-blown grass, Alan accidentally stepped on something alive. It was a rather large lizard who'd been resting there, sluggish in the early sun. The weight of Alan's foot had broken off most of the lizard's tail, and it was frantically twitching on the ground. The lizard himself remained motionless. Alan had the notion the was wounded lizard was keeping himself under strict control, as opposed to his cut-off tail which had no control at all, desperately writhing.

With the federal police after him and his fellow skuggers, he needed to be like the lizard and not like the tail.

January 27, 2011

Painting of Monument Valley

Monument Valley, acrylic, 24″ x 18″, January 2011. More info at my Paintings page.

I started this en plein air at Monument Valley in September, 2010. We had some warm days this week, so I got out in my "studio" (the back yard) and finished this one. Acrylic for a change, which works better when you're carrying a painting around outdoors—it dries fast. Strong colors even if it is acrylic.

Those rock formations on the left are called the Mittens. This is an amazing place, with a strong spiritual vibe. The day after I painted this, I got up before dawn and hiked down into the valley, around the mitten on the left, and back up—which took about four hours.

If you ever get a chance, go there and stay at THE VIEW, the Navajo-run motel right there with this view.

January 25, 2011

Cronenberg's NAKED LUNCH as Transreal SF

For whatever reason, most people don't think of William Burroughs's novel Naked Lunch as science-fiction, but really it is. In particular, it's what I call Transreal SF, that is, a form of autobiography in which one's experiences are made more vivid by transmuting them into SFictional tropes, see for instance my talk, "Power Chords, Thought Experiments, Transrealism, and Monomyths."

[image error]

[Hummingbird and Orchid by Martin Johnson Heade.]

Burroughs himself often wrote admiringly about SF in his letters, and said that's what he was indeed writing. But people ignore this. Perhaps it's that so few SF works aspire to such a high literary level, or that Naked Lunch doesn't have a straight-through plot-line. But if you look at the tropes in the book, it really is SF¬—aliens, imaginary drugs, telepathy, talking objects … the gang's all here.

I'm thinking about the book both because Burroughs is a character in my novel-in-progress The Turing Chronicles, and because I watched David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch via NetFlix instant-watch last night.

What great cinematography—the framing, the colors, the segues, the simple but telling effects. The acting is great too, it's understated, which is important—it's easy to go over into gauche, hammy stuff when portraying legendary figures like the Beats. Judy Davis is a wonder as Joan Vollmer (called Joan Rohnert in the film), and as Jane Bowles, also called Joan in the film.

And what a wonderful script. Cronenberg himself has the credit for the screenplay. You can find it online, transcribed from the movie by some fanatic, at Drew's Script-o-Rama. The novel Naked Lunch doesn't have a single clear plot-line that would make a movie—indeed the lack of such a plot is a key artistic element of the book, and a key aspect of the mythos around the book.

For the purposes of the film, Cronenberg created what Wikipedia terms a "metatexual adaptation." That is, he blended elements of the novel with the by-now-legendary story of Burroughs's life—the shooting of his wife, the expatriate years in Tangier, typing the pages of Naked Lunch high in his Tangier room, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg helping him assemble the manuscript. All of this material is outlined in Burroughs's letters, and in the reminiscences of his Beat friends—the transreal oeuvre is blended together to produce the transreal film.

It's a brilliant move on Cronenberg's part to have the typewriters be alien beings. For a writer in those pre-computer days, a typewriter was an object of great mana. A partner, a friend, a tool—more reliable than any computer ever is. I remember in 1982 going on a trip with nothing in my suitcase but underwear, my pink IBM Selectric typewriter and some Clash and Ramones records. And to have these machines become talking insects or alien heads is a great concept.

Cronenberg made two marketing moves to enhance the film's general appeal.

First of all, rather than having the main character be addicted to opiates, the Bill Lee of the movie is addicted to not-quite-real substances like cockroach-extermination-powder and the powder of the "black meat," taken from very large fresh-water Brazilian centipedes. Burroughs himself used this move in the novel—rather than going on and on about heroin as he'd done in Junkie, which is a turn-off for many readers. In Naked Lunch , the characters are obsessed with these more science-fictional drugs.

The second market-friendly move by Cronenberg—which aroused the ire of some—is that he plays down his Bill Lee character's homosexuality. To some extent this fits with the Burroughs of the early 1950s. Bill was, after all, married for a time—before he shot his wife. And, judging from his letters, he was always put off by overly flamboyant flaunting of one's homosexuality. One gathers from Burroughs's work that there there was a definite transition period for him in the early 1950s, and Cronenberg sets his character in the period of the transition.

By time Burroughs was actually living in Tangier, he was well past the transition, constantly writing about boys in his letters, so in that sense the film is historically inaccurate. But we're not talking about true history in the movie Naked Lunch . We're talking about attaching the images and dialog of an author's fantastic novel to a mythologized version of the author's life. And in some ways the transitional state is a good choice to use for the film. In any case the character is, as Burroughs remarked to Cronenberg re. the film, "queer enough."

I did find the ending of the movie a downer, to have Bill repeating the same dreadful mistake that he'd made near the start. Cronenberg is taking off on a possibly ill-advised remark by Burroughs to the effect that if he hadn't shot Joan he might not have become a writer. That's not a place that most of us want to go.

For my taste, it always a little cheap and obvious to give a novel or a movie a serious feel by using a hard, downbeat climax. What's the line? "Tragedy is easy, comedy is hard."

[image error]

One of my favorite bits in the film is when the Burroughs character is talking to the Paul Bowles character, and the older man is telling Bill all these shocking intimate things about himself, and Bill says, "I'm surprised you're telling me all this," and Bowles says, "Well, I'm not saying it out loud. The conversation you're hearing is telepathic. You see, if you look closely, the words you're hearing don't match the motions of my lips."

Another great bit is when Bill is passed out on the beach with, he thinks, his broken typewriter in a gunny-sack. And Jack and Allen show up to cheer him up. And Bill mumbles, "A little trouble with my typewriter." And the boys look in the sack, and all that's in there is trash—empty pill bottles and cans and bottles. "My typewriter."

January 24, 2011

The Classic CHAOS Software Goes Multiplatform

Today I got around to using a fix that allows our old CHAOS software to run, I think, on every platform. See my CHAOS page for full details, and for the free downloads. Thanks to "Torbjørn Pettersen" and "Jac" for having advised me.

Summarizing some of that that page says, CHAOS is a shareware release of James Gleick's CHAOS:the Software. We provide both the complete executable and the source code for the 1990 Autodesk release based on the wonderful book Chaos, by James Gleick.

The software was written by Josh Gordon, Rudy Rucker and John Walker for Autodesk, Inc., with Josh Gordon doing the lion's share of the programming work. It is our hope that this shareware release will allow educators, students and dabblers to freely use our software. Great for classroom use or individual exploration.

CHAOS can presently be run, using the free DOSBox ware, under Windows, Linux, Mac OS X, and other platforms.

CHAOS has six modules.

1. MANDEL. A fast Mandelbrot set program, incorporating: quadratic and cubic Mandelbrots, various fill patterns, quadratic and cubic Julias, and the gnarly "cubic Mandelbrot catalog" set that I call the Rudy set. For more up-to-date info on these fractals, you can also look at my 2010 formula files and parameter files for the commercial Ultra Fractal software as described on mys blog post, "The Rudy Set as the ultimate Cubic Mandelbrot."

2. MAGNETS… A Pendulum and Magnets program showing chaotic physical motion.

3. ATTRACT. A Strange Attractors program showing some of the Hall of Famers as the Lorenz Attractor, the Logistic Map, the Yorke Attractor, the Henon Attractor, etc.

[image error]

4. GAME. A "Chaos Game", which is a Barnsley Fractals program showing Iterated Function System fractals such as the famous "fern".

5. FORGE. A "Fractal Forgeries" program that shows mountain ranges based on random fractals.

6. TOY. A "Toy Universes" program that shows some cellular automata.

January 21, 2011

Unpredictability and Plotting A Novel

I was happy for a few days last week about a new outline for my novel-in-progress, The Turing Chronicles , and I posted about the outline in, "Reading in SF. New Outline. Ripping Vinyl." But now that I'm down to actually implementing it, it's clear that the outline has a big hole in the middle. Not enough plot. So I'm re-doing it again, on the side, while I continue work on the new chapter.

[image error]

[A great African mask in the African collection upstairs at the DeYoung museum.]

I think I will need something like what I was calling "dreamskugs" after all, that is, some incorporeal beings who one see from the corners of one's eyes. But that isn't the right name for them, for any talk about dreamskugs blends with and muddies the biocomputational skugs that Alan Turing discovered/invented/enabled. The spirit-things need their own name. So I'll call them gazaks for now. An onomatopoeic word mimicking, say, Alan's anxious grinding of his teeth and or retching at their initial appearance. "Gaaak!"

["Turing and the Skugs". More info on my paintings site. I can't get enough of this painting! Pretty soon I might try and paint some gazaks too.]

I see the gazaks as elemental spirits, elves, discarnate ghosts, or perhaps minds as software images embodied in nature's flows. Their interaction with us might as well be what potentiated the appearance of Turing's skugs. The gazaks "saw" Turing on the verge of providing a biocomputational interface to link the two worlds, and they helped him make it happen. And then, near the end of the book, the gazaks soul-suck a lot of people off into their world, which may or may not be a pleasant place.

[image error]

I've always felt that it's okay to keep revising my plot outline as I go along. This dovetails with a lesson I've learned at a deep level over the years, to wit: "The World is Unpredictable." I in fact have a very short essay with this title in this year's edition of superagent and tummler John Brockman's "World Question Center, 2011". He got about a hundred and sixty people to answer the question, "What scientific concept would improve everybody's cognitive toolkit?" You can find the index on the site indicated, I'm at the bottom of Page Two of the answers.

[image error]

Unpredictability not only to the world at large, but to your personal life, as I describe in my 2004 blog post, "Free Will." That is, even if the world is in some scientific sense deterministic, we cannot in practice to predict what we'll be doing tomorrow. I wrote about this at some length in my tome on computation and the mind, The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul,,

[Escaped tulpa from my novel "Jim and the Flims," recently spotted in Los Gatos.]

But my point in today's post is that unpredictability is being very much an aspect of how one dynamically works with the outline of a novel in progress. Quoting from my short how-to book, "A Writer's Toolkit," as revised in 2009.

When you're writing a novel you're working at the most extreme limit of your capabilities. What you're doing is beyond logic, so far out at the limits of what you can do that there's no hope of your having a short and manageable simulation of the process by which to figure out what you're doing, it's computationally irreducible. When you get into this zone, out on the very surface of your brain, you become sensitive to the tiniest chaotic emanations of the world outside. At times it feels as if the world, feeling your sensitivity, gladly dances back. Dosie-do. Keep your eyes peeled.

[image error]

[Aardvark mask, also in the DeYoung.]

I've known this for quite a few years, but I'm always learning it at deeper levels. Here's a quote from my "A Transrealist Manifesto" of 1983:

The Transrealist artist cannot predict the finished form of his or her work. The Transrealist novel grows organically, like life itself. The author can only choose characters and setting, introduce this or that particular fantastic element, and aim for certain key scenes. Ideally, a Transrealist novel is written in obscurity, and without an outline. If the author knows precisely how his or her book will develop, then the reader will divine this. A predictable book is of no interest. Nevertheless, the book must be coherent. Granted, life does not often make sense. But people will not read a book which has no plot. And a book with no readers is not a fully effective work of art. A successful novel of any sort should drag the reader through it. How is it possible to write such a book without an outline? The analogy is to the drawing of a maze. In drawing a maze, one has a start (characters and setting) and certain goals (key scenes). A good maze forces the tracer past all the goals in a coherent way. When you draw a maze, you start out with a certain path, but leave a lot a gaps where other paths can hook back in. In writing a coherent Transrealist novel, you include a number of unexplained happenings throughout the text. Things that you don't know the reason for. Later you bend strands of the ramifying narrative back to hook into these nodes. If no node is available for a given strand-loop, you go back and write a node in (cf. erasing a piece of wall in the maze). Although reading is linear, writing is not.

[Cranes in the Amsterdam zoo.]

Finally, here's some more about the unpredictability of plot from "Seek the Gnarl," my Guest of Honor address at the International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts in 2005. A variant of this talk appeared in the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, and I also have this excerpt in the how-to book that I mentioned above, "A Writer's Toolkit.

With respect to plot structures, I see a spectrum of complexity. At the low end of complexity, we have standardized plots, at the high end, we have no plot at all, and in between we have the gnarly somewhat unpredictable plots. These can be found in two kinds of ways. I tend to use what I call the transreal approach of by fitting reality into a classic monomythic kind of plot structure and using some standard (say) science-fictional tropes. In the less flashy, but perhaps even more complex realistic mode, you try and mimic the actual world very precisely, working hard to avoid overlaying received ideas and cliches. In some ways, truth really is stranger than fiction. And so I view transreal fiction as a bit less computationally complex due to its position at the nexus of reality, fantasy, and the trellis of a classic plot structure such as the monomyth.

Complexity

Literary Style

Characteristics

Techniques

Predictable

Rote

A plot very obviously modeled to a traditional pattern.

Monomyth

Medium gnarl

Transrealism

Traditional story pattern enriched by realism. Observation acts on the fictional tropes to create unpredictable situations.

Realism + monomyth + power chords

High gnarl

Realism

A plot modeled directly on reality, with the odd and somewhat senseless twists that actually occur.

Observation, journals

Random

Surreal

Completely arbitrary events occur. (Tricky, as the subconscious isn't all that random.)

Dreams, whims, external input.

Yum! The muse wants to help you.

Rudy Rucker's Blog

- Rudy Rucker's profile

- 583 followers