Rudy Rucker's Blog, page 46

December 11, 2011

More NESTED SCROLLS. Los Gatos TEDx Talk.

Oddly enough, I happened to give two TEDx talks in the last couple of months. In my most recent post, I embedded a link for the talk on "Beyond Machines: The Year 3000," which I gave in Brussels in November. Today I'm embedding a link for the TEDx talk, "Transreal in Los Gatos," which I gave in October.

The "Transreal in Los Gatos" talk is a more autobiographical than the Brussels talk, and discusses some of the stories and events that are in my autobiography, Nested Scrolls.

Further promo for Nested Scrolls. The SF website io9 ran an excerpt called "The Death of Philip K. Dick and the Birth of Cyberpunk."of Nested Scrolls.

Cory Doctorow gave the book a mention in Boing Boing.

The Tor Books newsletter ran my description of the book under the title, "A Look Back at my Weird, Cool Life"

And SF writer John Scalzi's blog Whatever ran my account of the book as "The Big Idea: Rudy Rucker."

December 4, 2011

NESTED SCROLLS. Brussels TEDx Talk.

So I decided that I'd better write my autobiography before it was too late. What with death and senility closing in!

I didn't want my autobio to be overly long or dry. I wanted it to read something like a novel. Unlike an encyclopedia entry, a novel isn't a list of dates and events. A novel is all about characterization and description and conversation, about action and vignettes. I wanted to structure my autobiography, Nested Scrolls , like that.

The U.S. edition of Nested Scrolls comes out from Tor Books this week. You can order the hardcover or ebook Tor edition from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or direct from Tor. The Tor site has links for independent booksellers and further ebook formats.

Note that a more expensive collector's edition is available from PS Press in England.

There's a fashion these days for making video trailers for books. The following isn't precisely about Nested Scrolls, but it will do. It's a recent TEDx talk that I gave in Brussels covering a lot of the ideas that I touch on in my autobio.

And here's a nice blurb from Regina Schroeder at Booklist :

This is a wild memoir, certainly as satisfying a read as any of Rucker's novels… He knew from an early age that he wanted to be a beatnik writer, and in many ways, he has succeeded—in others, of course, he has surpassed his inspiration. It is, being the story of a life, not an easy road: there is trouble with his parents and with his wild-man lifestyle, and with work and sheer existence. By the end of the volume, though, the reader has a sense that it's been an interesting and well-lived life, and it makes for a fascinating story, even the time he spends as a math teacher. This reads like Rucker's novels, packed with adventures, filled with humor, and often quite surreal.

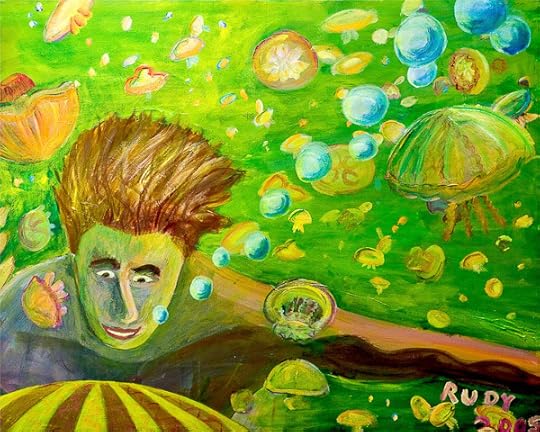

Here's a photo of me in Jellyfish Lake in the South Pacific. Think of this as an image of me swimming around inside my mind—surrounded by ideas.

Another blurb, from Rick Kleffel, in his online site, The Agony Column :

What distinguishes Nested Scrolls is Rucker's voice, which has this sort of steely, understated clarity. He writes in an almost flat, declarative style, which makes his rather amazing life all the more entertaining. He moves with equal ease through the halls of academia, science and science fiction. He effortlessly pushes the envelopes of math, technology, writing and art. He's told us many stories chock full of verve and imagination, but his own story may be the most powerful he has to tell. … Perhaps, just perhaps, Nested Scrolls will change what people think, not just of Rucker but books.

This is a picture of me in the early 1980s, using my beloved IBM Selectric to write my novel Wetware, the cyberpunk classic that would win me my second Philp K. Dick award. At that time I was a freelance writer, i.e. unemployed. My family and I were living in Lynchburg, Virginia, of all places. I was the lone cyberpunk in evangelist Jerry Falwell's home town.

I put a ton of other old photos online for Nested Scrolls.

The picture above shows me with a cone shell in 2004. I'm imagining that it's sending alien thoughts into my head. For a more accurate description of how I wrote my autobio, see the free Notes for Nested Scrolls, a booklength PDF file of my writing notes, about 600 Meg.

And the plot for my autobiography? Well, okay, a real life doesn't have a plot that's as clear as a novel's. But, as a writer, I can think about my life's structure, about the story arc. And I'd like to know what it was all about. In writing my autobiography, I came up with a few ideas.

You might say that I searched for ultimate reality, and I found contentment in creativity. I tried to scale the heights of science, and I found my calling in mathematics and in science fiction. You don't have to break the bank of the Absolute. Learning your craft can be enough.

As a youth, I was a loner. But then I found love and became a family man. I've spent a lot of time with my wife and our three children over the years. And now we have grandchildren. New saplings coming up as the old trees tumble down.

I've had a number of careers. Initially I was a math professor—math always came easy for me. Nothing to memorize! Then I took up writing, really that's my core career. But, even with thirty-odd books out, writing doesn't pay very much.

To make ends meet, I spent the last twenty years working as a computer science professor in Silicon Valley. Riding the wave. It was a blast. And eventually I even got good at teaching, mutating from a rebel to a somewhat helpful professor.

My autobiography's title has to do with the notion of stories unfolding within stories—and the title also relates to a certain kind of computer graphic I did research on, cellular automata. An example appears above.

My book in a nutshell? Whatever I did, I never stopped seeing the world in my own special way, and I never stopped looking for new ways to share my thoughts.

Nested Scrolls

So I decided that I'd better write my autobiography before it was too late. What with death and senility closing in!

I didn't want my autobio to be overly long or dry. I wanted it to read something like a novel. Unlike an encyclopedia entry, a novel isn't a list of dates and events. A novel is all about characterization and description and conversation, about action and vignettes. I wanted to structure my autobiography, Nested Scrolls , like that.

The U.S. edition of Nested Scrolls comes out from Tor Books this week. You can order the hardcover or ebook Tor edition from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or direct from Tor. The Tor site has links for independent booksellers and further ebook formats.

Note that a more expensive collector's edition is available from PS Press in England.

There's a fashion these days for making video trailers for books. The following isn't precisely about Nested Scrolls, but it will do. It's a recent TEDx talk that I gave in Brussels covering a lot of the ideas that I touch on in my autobio.

And here's a nice blurb from Regina Schroeder at Booklist :

This is a wild memoir, certainly as satisfying a read as any of Rucker's novels… He knew from an early age that he wanted to be a beatnik writer, and in many ways, he has succeeded—in others, of course, he has surpassed his inspiration. It is, being the story of a life, not an easy road: there is trouble with his parents and with his wild-man lifestyle, and with work and sheer existence. By the end of the volume, though, the reader has a sense that it's been an interesting and well-lived life, and it makes for a fascinating story, even the time he spends as a math teacher. This reads like Rucker's novels, packed with adventures, filled with humor, and often quite surreal.

Here's a photo of me in Jellyfish Lake in the South Pacific. Think of this as an image of me swimming around inside my mind—surrounded by ideas.

Another blurb, from Rick Kleffel, in his online site, The Agony Column :

What distinguishes Nested Scrolls is Rucker's voice, which has this sort of steely, understated clarity. He writes in an almost flat, declarative style, which makes his rather amazing life all the more entertaining. He moves with equal ease through the halls of academia, science and science fiction. He effortlessly pushes the envelopes of math, technology, writing and art. He's told us many stories chock full of verve and imagination, but his own story may be the most powerful he has to tell. … Perhaps, just perhaps, Nested Scrolls will change what people think, not just of Rucker but books.

This is a picture of me in the early 1980s, using my beloved IBM Selectric to write my novel Wetware, the cyberpunk classic that would win me my second Philp K. Dick award. At that time I was a freelance writer, i.e. unemployed. My family and I were living in Lynchburg, Virginia, of all places. I was the lone cyberpunk in evangelist Jerry Falwell's home town.

I put a ton of other old photos online for Nested Scrolls.

The picture above shows me with a cone shell in 2004. I'm imagining that it's sending alien thoughts into my head. For a more accurate description of how I wrote my autobio, see the free Notes for Nested Scrolls, a booklength PDF file of my writing notes, about 600 Meg.

And the plot for my autobiography? Well, okay, a real life doesn't have a plot that's as clear as a novel's. But, as a writer, I can think about my life's structure, about the story arc. And I'd like to know what it was all about. In writing my autobiography, I came up with a few ideas.

You might say that I searched for ultimate reality, and I found contentment in creativity. I tried to scale the heights of science, and I found my calling in mathematics and in science fiction. You don't have to break the bank of the Absolute. Learning your craft can be enough.

As a youth, I was a loner. But then I found love and became a family man. I've spent a lot of time with my wife and our three children over the years. And now we have grandchildren. New saplings coming up as the old trees tumble down.

I've had a number of careers. Initially I was a math professor—math always came easy for me. Nothing to memorize! Then I took up writing, really that's my core career. But, even with thirty-odd books out, writing doesn't pay very much.

To make ends meet, I spent the last twenty years working as a computer science professor in Silicon Valley. Riding the wave. It was a blast. And eventually I even got good at teaching, mutating from a rebel to a somewhat helpful professor.

My autobiography's title has to do with the notion of stories unfolding within stories—and the title also relates to a certain kind of computer graphic I did research on, cellular automata. An example appears above.

My book in a nutshell? Whatever I did, I never stopped seeing the world in my own special way, and I never stopped looking for new ways to share my thoughts.

November 14, 2011

TEDx. Beyond Machines: The Year 3000.

I'm going to be in Brussels next week to give a talk at TEDx Brussels, on November 22, 2011, at the Bozar building in Brussels. Today's post consists of the slides and the outline of the fifteen-minute talk I plan to deliver.

By the way, if you live in Brussels and Berlin and want to get together while I'm over there this month, send me an email.

[image error]

In my talk I'll speculate about the year 3000. A thousand years from now.

I first came to Brussels here in 2000 to do some research for my novel about Peter Bruegel's life, As Above So Below: A Novel of Peter Bruegel. And in 2002, I was here as a guest of the Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Science and the Arts.

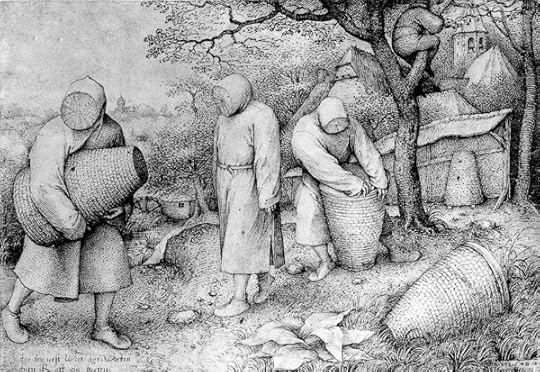

The picture shown above is called The Beekeepers. It's disturbing and surreal. Bruegel drew this image in 1568, shortly after the patriots, the Count of Egmont and the Count of Hoorne were beheaded at behest of the Spanish Inquisition. My sense is that those straw hives represent the baskets into which Count Egmont's and Count Hoorne's heads dropped after being lopped off by the executioner's sword in the Grand Place.

The image has some relevance to my talk, as a human head, is after all, a rather compact and intense information storage device, and I'll be discussing the notion of a "lifebox" model of a human personality.

I got a Ph. D. in mathematics, and I've published popular science books about infinity and about the fourth dimension. I spent about twenty years as a computer science professor at San Jose State. And over the last ten years I've become something of a painter—and you'll see some of my pictures here. But the the main thing I do is to to write science fiction novels. By now I've published twenty of them.

In 1982, I published my early cyberpunk novel, Software. The book introduced a theme I've been thinking about for my whole career. Is it possible to copy a person's personality and essence into another medium? In Software, my notion was that some helpful robots were copying people's brains by slicing them up—extracting the human software. And the software was being put onto robot bodies. That woman on the cover is an android, you understand. Software and three follow-up novels are available now as the Ware Tetralogy.

I do see this as being something that will happen in the next thousand years. In the very near term, we already have a simple way for mimicking the process, something that I call lifebox software. The idea behind a lifebox is get a large and rich data base with a person's writings, videos of them, interviews, and so on. That's the back end. The front end of a lifebox is an interactive search engine. This will be a huge commercial business soon. I've even made a preliminary attempt at a Rudy's lifebox.

Back in the mid 1980s, I became fascinated with a new style of parallel programs called cellular automata or CAs. I learned about them from Stephen Wolfram. I was interested in his remarks that some cellular automata are universal computers.

I wrote this early CA in assembly language, and the display is made of ASCII characters. I call this particular CA Maxine Headroom after the then-popular animatronic TV character Max Headroom. You can get this program as part of the free Cellab software online.

Although I was getting my novels published I wasn't earning enough money to support myself, my wife and our three children. I decided to get into computer science. Even though my Ph. D. was in mathematical logic, in 1986 I was able to get a job as a computer science professor at San Jose State University in California.

In principle any universal computer can emulate a human mind. And many natural systems behave like cellular automata. So I began wondering if there might be some way to have natural objects become programmable in an easy way.

Above is an image of me clowning with a South Pacific cone shell. The cone shells are beloved by fans of cellular automata, as it's widely believed that the shells' patterns are generated by a biological process very similar to a cellular automaton. Here I'm imagining that the cone shell will somehow connect to my brain.

In the years to come, I got ever more involved involved with CAs. The way they work is that, in a CA, you can think of the onscreen pixel as being a little computer, with all of them updating in parallel. One trick that I liked to use continuous values for the states of these pixels or cells, see my free software CAPOW, available online.

Perhaps my favorite CAs are the ones that spontaneously take on the appearance of ever-turning nested scrolls. These guys are called Belousov-Zhabotinsky scrolls, They're are common in physics—as patterns of turbulent wakes. And they're ubiquitous in biology—you find Zhabotinsky scrolls in mushroom caps, shells, beans and fetuses. Some have argued that everything in the world is a CA.

I spent hundreds and hundreds of hours staring at CAs. I was always looking for the gnarly ones, that is the CAs whose pattern is nicely positioned between order and randomness. I like using the more California word "gnarly" instead of "complex" or "chaotic."

Working as a programmer, I learned the frustration of working with the brittle computing machines. If you omit a semi-colon in a novel, the novel doesn't disappear—as can happen with a program.

Thinking as a science-fiction writer, I liked to imagine having a completely smooth interface between myself and the outer world—which I've painted as a torus here. I was still thinking in terms of a cable into my spine at this point. You can see all of my paintings online.

Where will end up in a century or two will be a device that sits on the back of your neck and communicates with other people via their devices. I call these things uvvies in my science fiction novels.

An uvvy link is very close to telepathy. I think we'll get true telepathy when, instead of sending information to someone else, you simply send them a link to the location where that information is stored in your own brain. And they can access it there without copying it. Relative to you, other people are part of your data cloud.

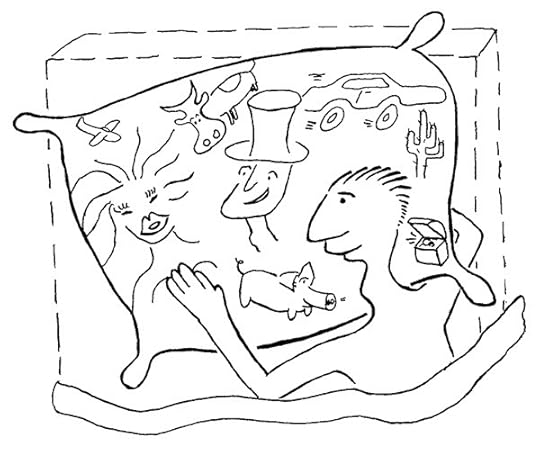

This picture shows a pathological regress you might encounter with telepathy. Like pointing a video camera at its output screen. An infinite regress. But there's nothing really wrong with that kind of experience. It might even be fun. This drawing and the ones to follow are taking from my novel, Saucer Wisdom.

At this point I was getting more and more interested in biocomputation. I think an uvvy might well be a biotech device—probably you want anything that interfaces that closely with your body to be alive.

A much easier biocomputation app we're likely to see is a substance similar to the skin of a cuttlefish. Call it squidskin for short. We'll be using squidskin as an inexpensive all-purpose display. This guy has a squidskin pillow so he can look at nice things in bed.

I like to use the word wetware when talking about hacking genomics. I'm taking wetware to mean the genomic information that generates a living organism. An acorn is the wetware for an oak tree, an egg is the wetware for a chicken, a person's wetware is their DNA.

I don't see nanotech as a separate discipline. It's really about learning to work with the biotech already present in nature. To become a wetware engineer.

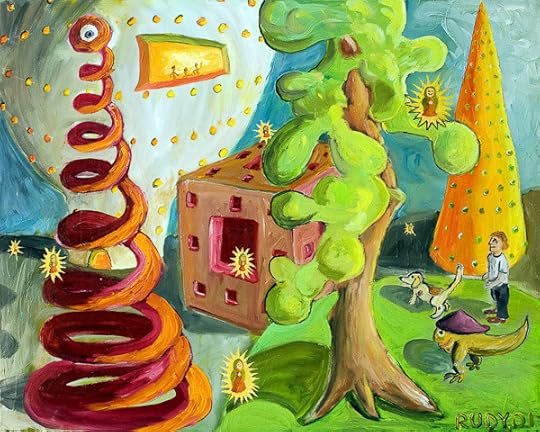

Looking towards the year 3000, I expect that we will have gotten very good at wetware engineering. This painting show a future city in which all of the buildings—except for that tree in front—have been grown.

Note also the Bosch-style little man in the lower corner. And the floating little figures might be taking the place of surveillance cameras. For some reason each of them shaped like the Virgin Mary. This painting was made for my novel Frek and the Elixir, which is set in the year 3003.

Naturally we'd like to grow our own houses. I think of a seed about the size of a pizza, and you shove it in the ground. I like the idea of a family living inside a kind of oak tree with squidskin on the inner walls.

I see the tree as being powered off photosynthesis. It has toilets in the walls that feed into the tree's metabolism. It extracts metal from the ground and grows an electrical circuit, in case we're still using electricity. The internal plumbing system extracts water from a tap-root that grows down to the water table.

The people have symbiotic wings they can strap on. I know there's an energy problem in human flight—we'll assume the wings are powered with, let us say, dark matter.

We can expect wetware engineered plants to grow any kinds of objects that we need. Here you see a plant like a corn stalk, except it extracts iron from the soil and forms a knife at its tip. A stub of the stalk makes a nice handle.

In the early 2000s, I became interested in the notion of moving beyond biocomputation as well If we take seriously the notion of quantum computation, anything at all can be a computer.

The notion that I'm leading up to is hylozoism. This is a real word, you can find it in Wikipedia. I got so enamored of this word that I even wrote a novel called Hylozoic, in which everything is alive—even the rocks.

A stone is, after all, like a jiggling mass of a septillion atoms, connected by spring-like bonds. There's a lot happening inside a rock. Why shouldn't it be as intelligent as I am?

In a hylozoic society of the year 3000, we don't use manufactured tools anymore.

Instead we directly program the material objects around us. Every object is filled with quantum wave functions. Every object is programmable. Every object is alive. You only have to tell it what to do.

And how do you talk to the objects? Via our uvvies—that is, via something like telepathy.

Here's a matching pair of images—just for fun.

This painting shows a weird scene in our biocomputational future. Think of it as a year 3000 disco.

And here's a pattern of cellular automata that underlies the year 3000 disco. This is what our world is like a smooth field of quantum computation. That's all that's there. And we only interpret the patterns as being things like green potatoes and dancing ducks?

And after the year 3000? Perhaps we leave our bodies and turn into light. Or maybe into subdimensional jellyfish, as I discuss in my novel Mathematicians in Love.

I'll see you there!

November 4, 2011

Point Reyes+Quantum Tantra+Magic Trip=SF

Today's seemingly unrelated pictures stem from a three-day hiking trip that my wife and I did with some friends in the Point Reyes National Seashore earlier this week. Mainly we hit the Tomales Point trail and the Estero Trail. We stayed at a pleasant, inexpensive inn called the Tomales Point Resort.

I also posted some pictures of the Tomales Point trail back in 2008, in the context of a ruminative but not really despairing philosophical entry called "The Problem of Death."

Today's topic, however, has to do with a new angle on intelligence augmentation.

What are some ways in which people might become noticeably smarter? I'm not interested in brute-force approaches like shoving in more memory tissues or internalizing direct links to world wide web. The cool, SFictional thing would be if there were some in-retrospect-rather-obvious mental trick that we haven't yet exploited.

In this context I'm also thinking of my friend Nathaniel Hellerstein's notion that there could be some as yet undiscovered physical tool as simple as the wheel, screw, or lever. I think he used to call his thing the flippit.

Mind amplification tricks do exist. Think of how our effective intelligence improved with the advent of speech and of writing. In the mathematical realm, our ability to calculate got exponentially better when we started using positional notation. And the computer and the internet give us another big boost: rapid computation, stable external memory (like my notion of a lifebox), and the universal library of web search. It would be cool if there some non-technical mental trick that would make us much brighter.

One of the dreams of AI is that there may yet be some conceptual trick that we can use to make our machines really smart. The only path towards AI at present is to beat the problems to death with neural nets working on data-bases. Progress involves making the computers faster, the neural nets more complex, and the data bases larger. But what if there were some clear and simple insight, some big aha?

And—the kicker—the aha would work for human brains as well as for machines. We'd get IA (intelligence amplification) as well as AI (artificial intelligence).

Inkling of the aha: My thoughts aren't at all like a page of symbols—they're blotches and rhythms and associations. Is there any communicable way to truly describe one's real mental life?

And this is where I can use the mind-as-quantum-system notion of Nick Herbert's quantum tantra! So we get a lot smarter by using a form of mental quantum computation.

Seemingly irrelevant topic: The other day night we saw the Ken Kesey and Merry Pranksters movie, Magic Trip. The material was quite familiar to me from Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and from Kesey's Garage Sale anthology.

Unsettling to see some snippets of Neal Cassady doing motor-mouth speed rapping. "We're 4D minds in 3D bodies in a 2D world."

The whole cultural change thing being depicted is exciting—the flow from early Sixties with the Beats, to Tim Leary's high-minded proselytizing, to the Pranksters' street psychedelia, and thence to the mass fad for acid, including the birth of light shows and the Grateful Dead. I like the notion of the Dead noodling along to the trippers at the 1964-1965 acid tests.

I liked the scenes where Kesey meets Kerouac and then meets Leary, and the meetings don't click. The street surrealists meet the resentful alkie sentimentalist and the mandarin. Later in the film, apropos of his reduced role as a writer, Kesey says—with touches of sadness, shyness, embarrassment, and acceptance: "Maybe I fried my marbles."

And now—here's the point—I'm thinking that I could transmute the historical birth of the psychedelic movement into a theme for my next SF novel. It could all happen again—something I've always longed for. The so-called Sixties were way too short.

But this time we do it not via a drug, but via quantum tantra in Nick Herbert's sense, that is, via a new technique of mind-alteration that's not exactly meditation, but rather something more literally physics-based. At least initially, I'll take the physics route rather than any, like, Sufi or Zen mystic route.

Like Nick says, it would be so cool to see some laboratory physics break-through for QT (quantum tantra). This makes it interesting, dramatic, SFictional, and Silicon Valley. It's the angle that Nick's always hoped for. But then, later on in the novel, some visionary can see that the laboratory equipment isn't necessary, and that one really can enter a QT state on one's own—and now it can be some kind of mystic meditator that gets to this point, I'm thinking of a Japanese woman speaking odd English.

The QT movement hits with force of the psychedelic revolution—the excitement, the liberation, the public ignorance, the denunciations politicians, and the ensuing international fad.

It's worth recalling that in that historical period of the advent of acid, the atomic bomb was on people's minds, also the recent assassination of JFK. A heavy time. And—at least according to Magic Trip—the CIA were the ones who first started disseminating acid to the American public—under the guise of scientific tests.

So I might have a kicker where quantum tantra is a government invention of some kind. We might suppose that our leaders see QT as a kind weapon. They plan to send QT-heads into enemy cities, prepared to rip holes in space like psychedelic suicide-bombers. And naturally this goes wildly wrong…

Point Reyes+Quantum Tantra+MAGIC TRIP=SF

Today's seemingly unrelated pictures stem from a three-day hiking trip that my wife and I did with some friends in the Point Reyes National Seashore earlier this week. Mainly we hit the Tomales Point trail and the Estero Trail. We stayed at a pleasant, inexpensive inn called the Tomales Point Resort.

I also posted some pictures of the Tomales Point trail back in 2008, in the context of a ruminative but not really despairing philosophical entry called "The Problem of Death."

Today's topic, however, has to do with a new angle on intelligence augmentation.

What are some ways in which people might become noticeably smarter? I'm not interested in brute-force approaches like shoving in more memory tissues or internalizing direct links to world wide web. The cool, SFictional thing would be if there were some in-retrospect-rather-obvious mental trick that we haven't yet exploited.

In this context I'm also thinking of my friend Nathaniel Hellerstein's notion that there could be some as yet undiscovered physical tool as simple as the wheel, screw, or lever. I think he used to call his thing the flippit.

Mind amplification tricks do exist. Think of how our effective intelligence improved with the advent of speech and of writing. In the mathematical realm, our ability to calculate got exponentially better when we started using positional notation. And the computer and the internet give us another big boost: rapid computation, stable external memory (like my notion of a lifebox), and the universal library of web search. It would be cool if there some non-technical mental trick that would make us much brighter.

One of the dreams of AI is that there may yet be some conceptual trick that we can use to make our machines really smart. The only path towards AI at present is to beat the problems to death with neural nets working on data-bases. Progress involves making the computers faster, the neural nets more complex, and the data bases larger. But what if there were some clear and simple insight, some big aha?

And—the kicker—the aha would work for human brains as well as for machines. We'd get IA (intelligence amplification) as well as AI (artificial intelligence).

Inkling of the aha: My thoughts aren't at all like a page of symbols—they're blotches and rhythms and associations. Is there any communicable way to truly describe one's real mental life?

And this is where I can use the mind-as-quantum-system notion of Nick Herbert's quantum tantra! So we get a lot smarter by using a form of mental quantum computation.

Seemingly irrelevant topic: The other day night we saw the Ken Kesey and Merry Pranksters movie, Magic Trip. The material was quite familiar to me from Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and from Kesey's Garage Sale anthology.

Unsettling to see some snippets of Neal Cassady doing motor-mouth speed rapping. "We're 4D minds in 3D bodies in a 2D world."

The whole cultural change thing being depicted is exciting—the flow from early Sixties with the Beats, to Tim Leary's high-minded proselytizing, to the Pranksters' street psychedelia, and thence to the mass fad for acid, including the birth of light shows and the Grateful Dead. I like the notion of the Dead noodling along to the trippers at the 1964-1965 acid tests.

I liked the scenes where Kesey meets Kerouac and then meets Leary, and the meetings don't click. The street surrealists meet the resentful alkie sentimentalist and the mandarin. Later in the film, apropos of his reduced role as a writer, Kesey says—with touches of sadness, shyness, embarrassment, and acceptance: "Maybe I fried my marbles."

And now—here's the point—I'm thinking that I could transmute the historical birth of the psychedelic movement into a theme for my next SF novel. It could all happen again—something I've always longed for. The so-called Sixties were way too short.

But this time we do it not via a drug, but via quantum tantra in Nick Herbert's sense, that is, via a new technique of mind-alteration that's not exactly meditation, but rather something more literally physics-based. At least initially, I'll take the physics route rather than any, like, Sufi or Zen mystic route.

Like Nick says, it would be so cool to see some laboratory physics break-through for QT (quantum tantra). This makes it interesting, dramatic, SFictional, and Silicon Valley. It's the angle that Nick's always hoped for. But then, later on in the novel, some visionary can see that the laboratory equipment isn't necessary, and that one really can enter a QT state on one's own—and now it can be some kind of mystic meditator that gets to this point, I'm thinking of a Japanese woman speaking odd English.

The QT movement hits with force of the psychedelic revolution—the excitement, the liberation, the public ignorance, the denunciations politicians, and the ensuing international fad.

It's worth recalling that in that historical period of the advent of acid, the atomic bomb was on people's minds, also the recent assassination of JFK. A heavy time. And—at least according to Magic Trip—the CIA were the ones who first started disseminating acid to the American public—under the guise of scientific tests.

So I might have a kicker where quantum tantra is a government invention of some kind. We might suppose that our leaders see QT as a kind weapon. They plan to send QT-heads into enemy cities, prepared to rip holes in space like psychedelic suicide-bombers. And naturally this goes wildly wrong…

October 25, 2011

Talk at TEDx Los Gatos. Joan Brown show in San Jose.

On Wednesday, October 26, I'm giving a short talk for TEDx Los Gatos. At this point all the seats for the event are taken, but eventually videos will be available and I'll post a link to them here. The idea behind TEDx events is that they are set up to resemble the official TED talks, but any local group in the world can mount a TEDx, assuming they stick to certain guidelines.

[image error]

Here's a preview PDF file of my slides and text for my talk, "Transreal In Los Gatos." It's a large file, so when you click the link, it'll take up to a minute before you see the images onscreen. Note also that I'm still revising the text, and in the end it'll come out different during live performance.

[image error]

Sylvia and I were in downtown San Jose this weekend, nice to get a taste of city without driving all the way to SF.

[image error]

Downtown San Jose does tend to be a little deserted.

But they have a great patisserie called Bijan near the art museum.

[image error]

The San Jose Art Museum is an interesting building, expanded out from an old stone Post Office.

And they're having a show of paintings by Joan Brown (1938-1990). She hasn't had a big show around here since 1998, when there was a somewhat larger two-site show in Oakland and Berkeley. About the best book on Joan Brown was based on that show.

The SJ show is definitely worth a visit. I like the transreal, narrative quality of Brown's later paintings, and how they go right down into the subconscious.

October 17, 2011

Nick Herbert's Quantum Tantra

I visited Nick Herbert last month and we talked about his notion of quantum tantra once again. (Photos are here in an unrelated post.) Nick said that everything is alive and that, even you can't attain telepathy with objects, you can develop relationships with them. He says that you'll decide which object to relate to on the basis of affinity—just as you do when selecting friends. Nick suggest that the first things you'd want to be in touch with would be the organs of your body.

It was 2002 when Nick first started talking about quantum tantra to me, and I read the details in his brilliant essay, "Holistic Physics: An Introduction to Quantum Tantra." I used his ideas a bit in Frek and the Elixir and mentioned it in my non-fiction book, The Lifebox, the Seashell and the Soul. I've blogged about quantum tantra a few times before: here are the past blog links.

Nick points out that the brain is, like any physical object, a quantum system. And he feels that quantum mechanics accounts for our consciousness. Quantum systems can evolve in two modes:

(Chunky) In a series of discrete Newtonian-style wave-collapses brought on by repeated observations.

(Smooth) In a continuous, overlapping-universes style of evolution of state according to Schrödinger's Wave Equation.

Our communicable, standard mental content is all chunky, and this is the kind of thing we try and mimic when we write programs for artificial intelligence.

The abrupt transition from mixed state to pure state can be seen as the act of adopting a specific opinion or plan. Each type of question or measurement of mental state enforces a choice among the question's own implicit set of possible answers. Even beginning to consider a question initiates a delimiting process.

It's unpleasant when someone substitutes interrogation for the natural flow of conversation—and throws you through a series of chunky collapses. And it's still more unpleasant when the grilling is for some mercenary cause. You have every reason to discard or ignore the surveys with which institutions pester you.

Nick remarks that the smooth mode is closer to how our inner mental experience feels. That is, upon introspection, my consciousness feels analog, like a of wave on pond.

The continuous evolution of mixed states corresponds to the transcendent sensation of being merged with the world, or, putting it more simply, to the everyday activity of being alert without consciously thinking much of anything. In this mode you aren't deliberately watching or evaluating your thoughts.

The soul might perhaps be given a scientific meaning as one's immediate perception of one's coherent uncollapsed wave function, particularly as it is entangled with the uncollapsed universal wave function of the cosmos.

Nick says that it will require a new physics and a new psychology to specify the details of the correspondence between mental phenomena and quantum states.

You should be able to couple your smooth mental state to the state of another person (or even to the state of another object), and thus attain a unique relationship that Nick terms rapprochement.

A caveat here is that, for quantum theoretic reasons, the link between the two systems isn't of a kind that can leave memory traces, otherwise the link is functioning as an observation that collapses the quantum states of the systems, reducing the consciousness to the chunky mode. Nick speaks of a non-collapsing connection as an oblivious link.

Nick chuckles over the fact that cannabis reduces one's short-term memory to the point where, indeed, a stoned conversation could, at least figuratively, be thought of as an oblivious link.

If you don't remember anything about your rapprochement with someone or something, can it be said to have affected you at all? Oh yes. Your wave state will indeed have changed from the interaction, and when you later go and "observe" your mental state (e.g. by asking yourself questions about what you believe), you will obtain a different probability spectrum of outputs than you would have before the rapprochement.

Nick is a hylozoist—that is, he believes, as I do, that objects are alive and conscious. He proposes that both smooth and chunky consciousness can be found in every physical system. Thinking at a higher level, he remarks that synchronicity might be evidence that we're all parts of some higher being. The higher mind's ideas filter down into remote oblivious links.

If you want more, here's an entry on Nick's Quantum Tantra blog with a link to a video of him holding forth in Boulder Creek. (And it's not a coincidence that the word "tantra" is related to sex!)

October 14, 2011

Reading "The 57th Franz Kafka" Friday Night

Tonight, Friday, I'll be reading my weird old SF story, "The 57th Franz Kafka," under the auspices of the SF in SF group, who have arranged a Kafkaesque reading for the annual San Francisco Litquake festival. Doors (and drinks) at 6 pm, Readings start at 7 pm. Terry Bisson and Carter Scholz will be reading as well as me.

[image error]

And here's an R. Crumb-illustrated plug for our reading in the Huffington Post.

My story will be reprinted soon in Kafkaesque: Stories inspired by Franz Kafka, edited by John Kessel & James Patrick Kelly. Here's part of the story note that I wrote for this new anthology.

I wrote "The 57th Franz Kafka near the start of my literary career, in the spring of 1980. My wife and I were in Heidelberg for two years—I had a grant to do research on infinity at the Mathematics Institute of the university. During this period I read and reread the Penguin Modern Classics edition of The Diaries of Franz Kafka several times, drinking in Kafka's vibes and chuckling over the crazy letters he'd write to his relatives and to the family of his lady friend.

One aspect of Kafka's writing that's perhaps not as well-known as it could be is that Kafka himself considered his stories to be funny. His friend Max Brod reports that Kafka once fell out of his chair from laughing so hard while reading aloud from one of his works, perhaps from Die Verwandlung, that is, The Metamorphosis. Our puritanical and self-aggrandizing American culture tends to make out Kafka's work to be solemn and portentous. But it's funny in somewhat the same way as Donald Duck comics…

And here, just as a teaser, are the first two paragraphs of my dark tale:

Pain again, deep in the left side of my face. At some point in the night I gave up pretending to sleep and sat by the window, staring down at the blind land-street and the deaf river.

The impossibility of connected thought. Several times I thought I heard the new body moving in the long basin.

See ya there!

October 10, 2011

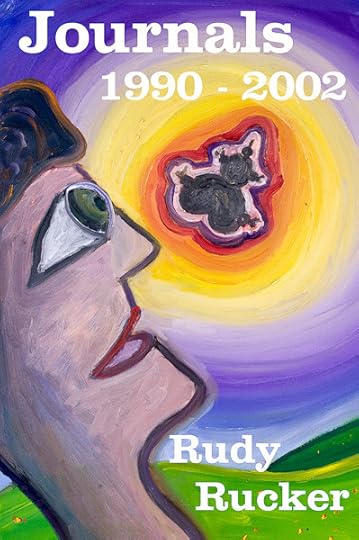

Journals: Alienation & Enlightenment.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I'm combining and polishing my collected journals for the twenty-one year period 1990 to 2011. I might publish them in some form next year, perhaps only as print-on-demand and as e-book. It'll be two volumes, one 1990-2002, the other 2002-2011. Here's a cool passage that I happened to be editing today. Today's illos are recent ones, from Los Gatos, Santa Cruz, and Ardenwood Farm.

It's early April, 2002, and I'm in Torino, Italy, to give some kind of talk. I'm now sitting on my bed in the City Hotel in Torino. The sound of opera singing from across the hall is very loud, I guess it's on their radio? Or maybe it's some live person or persons rehearsing opera? Bellowing. Cute, in a way. Just the thing to remind me I'm in Italy.

I go outside and do my my initial Mars Rover number, trundling around the streets. It's cold and raining. The streets are so Italian. It's so wonderful, so amazing that this parallel un-iverse is now and ever ongoing, and that all I have to do is to get in a plane and take a lengthy but not really all that difficult eighteen hour journey to access this plane of existence.

[image error]

I see a nice café on a side street full of women in pairs and threes and fours, sitting at tables drinking coffee and eating pastries, all of them talking to each other, all of them using their hands to talk, and the quick visual effect of looking in through the tinted glass was of a tide pool of anemones with their tendrils waving.

Now it's 2 am and I'm having this jet-lag insomnia Camper Van Beethoven Eyes of Fatima interlude.

"Take the hands off the clock—you're gonna be here for a whiiiiile."

(Camper Van plays this with warpy, snit-snit, down-the-wormhole bad-acid guitar licks in the background, you understand.)

I open the door to the night balcony and it's raining outside. I've been looking forward to this moment. There's nothing like jet-lag when you're traveling alone and you can turn the light on and fire up the lap-top, my drug of choice these days.

So now I'll work on my current novel. Or maybe on a journal entry.

What if I didn't have my books to define myself by? It would be tough—to just live in the light of day and not to have my daily scene lit by the footlights of the literary stage. It would mean going back to life at degree zero, like my life was when I was a young Nobody from Nowhere.

Yet even back then I had my portable footlight with me, its generator pooting along. What fuel was the footlight generator running on back then? Irony, viewing things at a remove. Drinking or getting high used to help with that. My concomitant physical malaise acted as objective correlatives for an artist's neurasthenic alienation.

An artist feels emotionally different from his or her fellows. But, just to deconstruct that old trope—from listening to people talk about themselves over the years, I've found that most people feel different from others. Even the seemingly bland dummies are alienated, it's just that the bland dummies don't have the talent for making a geschrei about it. A raucous tumult.

And, second deconstruction, it is occasionally possible to be, or at least to feign to be, a Whitmanesque yea-saying artist who fully embraces the daily things, like Jack K. going, "Wow, what great apple pie! With ice-cream on it! Yes!"

I had a little moment of that joy-with-the-given at the San Francisco airport, simply enjoying the architecture, the awesome height of the vaulted hall, the light glancing off the shiny stone floors and rendering everything in shades of greenish gray, and us travelers scattered about like the stylized figures in a maquette.

And I got another hit of that while changing planes in Amsterdam, simply looking out at the friggin' light poles around the airfield, enjoying how they were grouped. And here and now, for that matter, I take a simple, non-alienated joy in being awake alone at night in Italy, with the sound of rain outside, at the leading edge of spring, me here with my fingers and my words and my hard-drive, sketching, sketching, sketching.

"What a sweet thing is perspective," as Paolo Ucello used to say.

Ding dong goes the elevator, bringing my opera-singing neighbors back to their room. 3 am. I'm gonna be here for awhile.

Rudy Rucker's Blog

- Rudy Rucker's profile

- 583 followers