Carl Zimmer's Blog, page 81

October 5, 2010

Announcements, Announcements, cont'd: Me and Misha Considering His Genome

Misha Angrist has written an excellent book that you might just want to buy for its title alone: Here Is A Human Being. In this case, the being is Misha. He was one of the first people to have his genome sequenced, and he's chronicled the experience in this book.

Misha Angrist has written an excellent book that you might just want to buy for its title alone: Here Is A Human Being. In this case, the being is Misha. He was one of the first people to have his genome sequenced, and he's chronicled the experience in this book.

Here's the endorsement I sent to Misha's publisher back in the spring:

Our genomes pose a paradox. They are at once profoundly intimate and remotely abstract. Misha Angrist blasts the paradox apart with Here Is A Human Being. He bravely explores what it really means for him to be able to gaze at his own genome, not by simply considering the nature of his particular gene variants, but also probing the many ways that genomics is going to influence society as a whole. A fascinating, unique book.

The book is coming out at the start of November. To celebrate the occasion, Misha and I will "be in conversation," as they say, at Labyrinth Books in New Haven on Saturday, November 6, at 6 pm. Come join us!

October 3, 2010

Time for a Da Vinci Upgrade [The Microbiome Image of the Day]

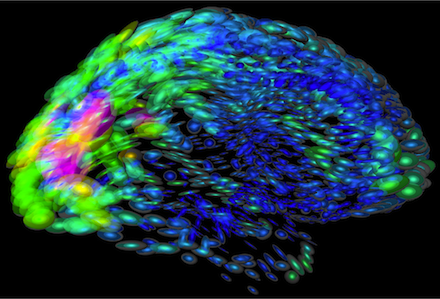

I've been invited to give a few talks in the wake of my article in the New York Times on the microbiome, and so I'm prowling for beautiful images that drive home the fact that we are microbial rain forests, rather than sterile mammals. Below is my favorite image of the day.

I've been invited to give a few talks in the wake of my article in the New York Times on the microbiome, and so I'm prowling for beautiful images that drive home the fact that we are microbial rain forests, rather than sterile mammals. Below is my favorite image of the day.

It's from a survey of microbes across people's bodies, published last year in Science. The inner circle shows the major lineages of bacteria found in all the subjects in each part of the body, while the ring shows the ones found in some people but not others.

This picture was stuffed away in the supplementary materials for the paper, so I missed it the first time around. I'm glad I found it–it's a new Vitruvian man for our microbiomic age.

September 30, 2010

The Vaccine Tree (Plus An Extended Deadline For The Science Ink Book) [Science Tattoo]

Shi-Hsia Hwa writes,

Shi-Hsia Hwa writes,

I'm a virologist in a biotech company in Singapore. Here's my story: I've been interested in infectious diseases since I was a kid, because my father almost died of TB when he was an infant. I must have been the only kid who looked forward to mass vaccination days in school. For a field trip to the Philippines after my bachelor's and my first job shortly thereafter, I had to be immunized against a lot of other things that the average person doesn't.

The choice of motif was inspired by a verse from the Biblical book of Revelation (a k a Apocalypse): "On each side of the river stood the tree of life, bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month. And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations." The "tree of life" motif in Western folk art is a tree bearing various different fruits on its branches.

I was stupid and didn't check the stencil after the tattooist smudged one part, which is why there are two "PV"s; one should have been "HAV" for Hepatitis A. Like everybody else in this part of the world, I've had the BCG but will not add a "TB" fruit until a truly effective tuberculosis vaccine is invented.

As I announced last month, I'm turning the Science Tattoo Emporium into a book called Science Ink. The ultimate purpose of the book, like the Emporium, will be to illustrate the passion that science can inspire. To that end, I also plan to donate a portion of the proceeds from the book to DonorsChoose, a great organization that funds science projects in the classroom.

In just a few weeks, I've been inundated with lots of book-ready images–not just bigger versions of the ones I've put on the blog, but many new ones as well. I originally set a deadline of October 1 (tomorrow), so that I and my designers could put the book together in time for its fall 2011 publication date. A day before the deadline, we've got many more images than we set as our target number, which is gratifying. But we keep getting last-minute emails from people like Shi-Hsia Hwa with more ink to offer. Who are we to turn our noses to this stuff?

So here's the deal: I'm extending the deadline to October 15. Contact me for submission details. And if anyone has had any trouble uploading their tattoo pictures, get in touch.

Click here to go to the full Science Tattoo Emporium.

September 29, 2010

Monkeys in the mirror and the nature of science

Charles Darwin wondered if animals were aware of themselves. Allowed to visit a rare orangutan in the London Zoo, he brought a mirror and observed the ape apparently make faces at its own reflection. It's hard to say for sure that the orangutan really was aware that its reflection was its own. Over a century later, a scientist named George Gallup turned Darwin's idea into a more rigorous test. He would secretly put a mark on an animal's forehead and see if it noticed the difference the next time it passed a mirror.

Human adults pass this test, but young children don't, suggesting that our self-recognition takes time to develop. Some chimpanzees (our closest relatives) seem to pass this mirror test, but others fail it. Orangutans also show mixed results. Beyond the primates, studies have indicated that magpies, dolphins, and elephants pass the mirror test. In a new paper in PLOS One, Luis Populin of the University of Wisconsin publish what may be the first compelling evidence that monkeys pass the mirror test too.

It's a surprising result because people have tried to find evidence of self-recognition in monkeys before. Most scientists failed. The Harvard primatologist Marc Hauser claimed in 1995 that the cotton-top tamarin could pass the mirror test, but that paper was one of several that Harvard now claims were tainted by Hauser's misconduct. Populin and his colleagues came across their first clues of self-recognition by accident. They had implanted electrodes in the skulls of rhesus monkeys for a different study. They keep mirrors in the monkey cages just to stimulate the animals, and they noticed that the monkeys started spending a lot of time looking at themselves in the mirrors after surgery.

To see if the monkeys were really aware that their appearance had changed, the scientists put different mirrors into the cages. Some were big and some were small. Some were made of ordinary glass, while others were painted glass. The monkeys looked much more often into the real mirrors than the blackened ones. The scientists then introduced an even bigger mirror into the cages, which allowed the monkeys to see their whole bodies. The mirror hung from the top of the cage so they could turn it around. The video above shows a monkey without an implant inspecting one of these big mirrors. It doesn't use any of the gestures it might if it met another monkey. Instead, it seems to be inspecting its body. Every nook and cranny, in fact.

I asked two experts on self-recognition, Lori Marino and Frans de Waal, both of Emory University, what they thought of the paper.

Marino was enthusiastic:

I've been reading this article over and over again all morning and have looked at the videos. Here is my reaction: I think that this is potentially a very important study. The videos are absolutely convincing. At first I thought it was the saliency of the implanted head device that made a difference but the videos show that monkeys without the device also use the mirror and, even more importantly, the monkeys are using the mirror to explore OTHER parts of their bodies, i.e. genitals. That can't be explained away in some sort of 'stimulus saliency' explanation, as far as I can tell. There are two areas that I wish I had more information about. First, exactly what was their prior mirror exposure? Is there anything they can report about how long that was and if there were any interactions with the monkeys during that prior time that could have made a difference in terms of the outcome of this study? Second, they report that the monkeys "failed the mark test" but there is no information given about the methods used in the mark test. It would be important to know how that was conducted.

With all that said, this is – by far – the most compelling evidence for MSR in monkeys to date. I have been trying to find an alternative explanation for the results – and haven't come up with one yet. I'll continue to return to it to see if any come to mind. I think that these findings show that self-awareness is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon as Gallup has asserted. I don't find this conclusion particularly surprising because it has been extremely difficult for anyone to come up with an explanation for the supposed "discontinuity" between great apes and monkeys. I think the reason for this is that there is none.

De Waal was more circumspect:

It is hard to say what is going on as the cap may be seen as a "supermark," as the authors call it, but it is of course a mark that is not only seen but also felt. As a result, the monkeys have two sources of feedback at the same time, the image in the mirror and the sensation of something new on their head. This is different from the classical mark test, which has only one source of information (visual). It seems clear that the convergence of these two sources of perception is helpful to achieve self-inspection, and this is an interesting finding, but the authors still need to explain why rhesus monkeys apparently cannot do the same with just the visual information.

The hallmark of the mark test is its spontaneity, purely on the basis of visual input, so in this sense this is different. Rhesus monkeys have been tested many times and never pass the test. I think you need to talk to Dr. Gordon Gallup and see what he thinks. It is unclear to me what to conclude, but this study is quite different from e.g. the magpie study, which applied a purely visual test.

The idea that mirror self recognition is a black & white distinction (you either have it or you don't) was first challenged in another monkey study that we conducted, in which we showed that capuchin monkeys do not seem to see a stranger in the mirror: they seem to distinguish the monkey in the mirror from another monkey, strange or familiar. As a result, we proposed a gradual scale of self awareness. The piece of intriguing information presented here may support this view, but I am sure many scientists would want more tests and more controls.

[Update: New Scientist reports that Gallup shares De Waal's reservations.]

This back-and-forth is not just interesting in itself, both for what it says about monkeys and what it says about ourselves. It also says something about science. If you read some of the more extreme comments about the Hauser affair, you'll find some people trying to indict the entire line of research into how human and animal minds evolved. This new paper, and its reception, shows just how absurd that radical rejection is. Science is bigger than individual scientists, and the mirror test will survive.

Announcements, Announcements, cont'd.: An Evening of Creation

[image error]Three weeks from today I'll be in New York to host a special screening of the movie Creation, a fictionalized account of Darwin's life starring Paul Bettany and Jennifer Connelly. It's a collaboration between the Science and Arts program at CUNY and the Imagine Science Film Festival (for which I'm serving as judge). After the movie, I'll moderate a talk with the director, John Amiel, and biologists Cliff Tabin and Sean Carroll (of deep homology fame). It should be an excellent evening.

Here are the details:

Wednesday, Oct 20, 7:00 PM

Elebash Recital Hall, at the CUNY Graduate Center on 5th Avenue at 35th St. (Map)

No reservations. First come, first seated.

September 28, 2010

Announcements, Announcements! First up: Michael Specter coming to Yale

I've got several announcements to post over the next few days. Many eggs are beginning to hatch.

I've got several announcements to post over the next few days. Many eggs are beginning to hatch.

First up: New Yorker staff writer Michael Specter will be coming to New Haven to give a public talk on Monday, and then talk to my writing class Tuesday morning. Specter is the author of many important articles about science and medicine, some of which became the basis for his recent book, Denialism: How Irrational Thinking Hinders Scientific Progress, Harms the Planet, and Threatens Our Lives. You can find more about him on his web site and hear him talk briefly about denialism during his recent TED lecture.

Michael will be speaking on Monday, October 4 at 4 pm at Morse College at Yale (302 York St.). It's a Master's Tea, which means we'll be gathering in a living-room-like setting, with real tea for those who want it. I organized a tea at Morse in the spring for Rebecca Skloot for her self-made book tour. Here's an article about it, complete with a photo of the comfortable furniture.

(Thanks go to the Poynter Fellowship for making Specter's trip possible!)

September 24, 2010

Gamers > Computers: My new podcast on crowdsourced biology

On my latest podcast, I talk to David Baker of the University of Washington about a remarkable new way of studying biology: turn a problem (protein-folding) into a game, and get 57,000 people to play. Check it out.

On my latest podcast, I talk to David Baker of the University of Washington about a remarkable new way of studying biology: turn a problem (protein-folding) into a game, and get 57,000 people to play. Check it out.

September 22, 2010

Big Picture: animals!

To know the Boston Globe's Big Picture is to love it. And this week they've organized some excellent pictures of animals in the news. Falling bears, gargantuan salmon, and more. Get thee to a photoessay!

Failing to appreciate doors, and other mysteries of brain space

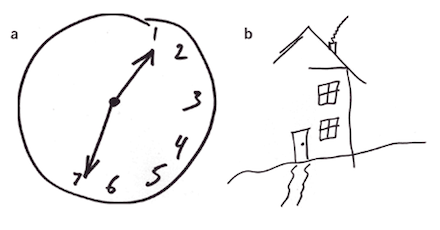

Yesterday I blogged about my new article in the Times about a new theory of consciousness. Today my latest column about the brain is posted at Discover's web site. I take a look this month at space. One of the most fascinating ways the brain can go awry is known as spatial neglect, in which people simply ignore part of the world around them. (These drawings were made by people suffering from one form of spatial neglect.)

In my column, I look at recent research that uses these...

September 20, 2010

What Is It Like To Be A Bat? What Is It Like To Be You?

In today's New York Times, I profile the neuroscientist Giulio Tononi, who has been obsessed since childhood with building a theory of consciousness–a theory that could let him measure the level of consciousness with a number, just as doctors measure temperature and blood pressure with numbers.

In today's New York Times, I profile the neuroscientist Giulio Tononi, who has been obsessed since childhood with building a theory of consciousness–a theory that could let him measure the level of consciousness with a number, just as doctors measure temperature and blood pressure with numbers.

There's one fascinating aspect of Tononi's work that I simply didn't have room for in a newspaper article (even with my editor's long-suffering generosity with the column inches). During each moment of ...