Carl Zimmer's Blog, page 77

December 7, 2010

Talking on the radio Wednesday at noon about arsenic life

Quick note: I'll be on the public radio show Word of Mouth show just after noon eastern time tomorrow (Wednesday 12/8) to talk about NASA's cookie full of arsenic. You can listen live here.

And the skeptics keep chiming in…George Cody on arsenic life

One of the challenges of writing on deadline is that people are not waiting every moment of the day to answer your questions. My Slate piece on arsenic life was based on a dozen or so responses from an overwhelmingly skeptical group of experts. And now, an hour after my story went live, I got a reply from George Cody, a chemist at the Carnegie Institution who co-authored a major 2007 "weird life" report. Rather than let this thirteenth comment molder in my inbox, let me share it with you. It's a bit technical but illuminating. I've condensed it for clarity (my clips marked by ellipses)–

One of the challenges of writing on deadline is that people are not waiting every moment of the day to answer your questions. My Slate piece on arsenic life was based on a dozen or so responses from an overwhelmingly skeptical group of experts. And now, an hour after my story went live, I got a reply from George Cody, a chemist at the Carnegie Institution who co-authored a major 2007 "weird life" report. Rather than let this thirteenth comment molder in my inbox, let me share it with you. It's a bit technical but illuminating. I've condensed it for clarity (my clips marked by ellipses)–

I have been aware of the hypothesis of the possibility of substitution of arsenate for phosphate for some time…The issue that always comes up is the facility of hydrolysis of arseno ester bonds….The correct experiment to do would be mass spectrometry which would unambiguously determine whether an arsenate backbone was present or not in the DNA. I cannot accept this claim until such an experiment (easily done) is performed. ..

I recall a summer intern in my laboratory accidently culturing up a bacterial biofilm from a solution of concentrated fumarate, urea, and ammonium hydroxide in ultra-pure water (not surprisingly ammonia oxidizing bacteria); we were surprised but evidently the microorganisms were able to obtain the necessary nutrients, e.g. phosphate, from somewhere to grow to a point be being readily observed. Microorganisms can do quite a bit with a little. I recall a report in Nature by Benjamin Van Mooy (WHOI) where it was shown that certain marine organisms could use sulfate in their lipids when the availability of phosphate is very low. Actually, if arsenate had substituted for phosphate anywhere, I would have looked at the lipids first, again using mass-spectrometry.

Philosophically, if it turned out that an organism could use arsenate in place of phosphate, this would not in my opinion rewrite the rules of life as we know it; aside from the hydrolysis issue, arsenate is chemically very similar to phosphate. A careful chemist could likely synthesize DNA oligomers with an arsenate backbone. As I understand it this is precisely why arsenate is a poison. Ultimately, the idea of a shadow biosphere is interesting, but it would have to be demonstrated to be truly distinct from extant biochemistry, e.g. truly novel metabolic pathways, different bases for coding, different amino-acids or better still enzymes that were not based on amino-acids at all.

As the old adage goes "Extraordinary claims require…"

Likely what I have said mirrors what you have heard from others.

Indeed, it has.

Arsenic life: My take on the backlash at Slate

Slate asked me to take a look at the scientific reactions emerging to last week's big news about arsenic-based life. I got in touch with a dozen experts, and let's just say, the results weren't pretty. Check it out.

Slate asked me to take a look at the scientific reactions emerging to last week's big news about arsenic-based life. I got in touch with a dozen experts, and let's just say, the results weren't pretty. Check it out.

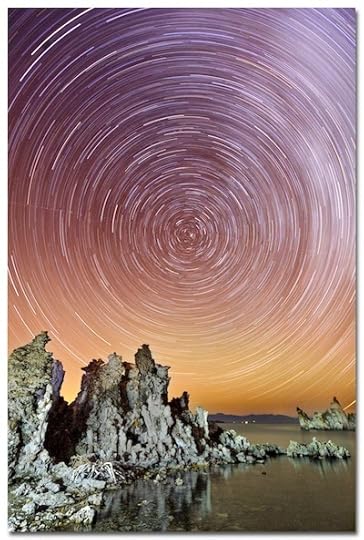

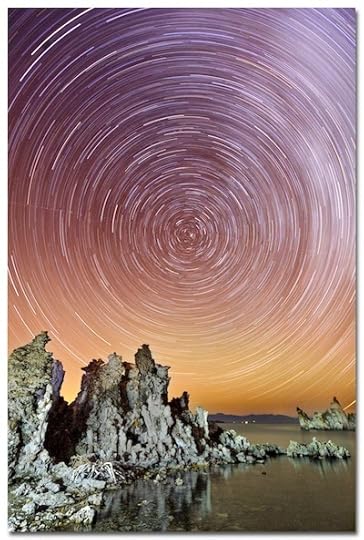

[Image of Mono Lake by .Bala via Flickr, under Creative Commons License]

December 2, 2010

Of Arsenic and Aliens

Rumors have been swirling this week about a press conference NASA is starting right now. Some people have speculated that they're going to announce evidence for life on another planet.

Rumors have been swirling this week about a press conference NASA is starting right now. Some people have speculated that they're going to announce evidence for life on another planet.

Well, not quite. Scientists have found a form of life that they claim bends the rules for life as we know it. But they didn't need to go to another planet to find it. They just had to go to California.

The search for alien life has long been plagued by a philosophical question: what is life? Why is this so vexing? Well, let's say that you're hunting for change under your couch so that your four-year-old son can buy an ice cream cone from a truck that's pulled up outside your house. Your son offers to help.

"What is change?" he asks.

"It's…" You trail off, realizing that you're about to get into a full-blown discussion of economics with a sugar-crazed four-year-old. So, instead, you open up your hand and show him a penny, a nickel, a dime. "It's things like this."

"Oh–okay!" your son says. He digs away happily. The two of you find lots of interesting things–paper clips, doll shoes, some sort of cracker–which you set aside in a little pile. But you've only found seventeen cents in change when the ice cream truck pulls away. Tears ensue.

As you're tossing the pile of debris into the trash, you notice that there's a dollar bill in the mix.

"Did you find this?" you ask.

"Yes," your son sobs.

"Well, why didn't you tell me?"

"It's not change. Change is metal. That's paper."

Scientists have proposed hundreds of definitions for life, none of which has emerged as the winner. (For more on this quest, see "The Meaning of Life," a cover story I wrote for SEED.) NASA, which would like to find life elsewhere in the universe, has taken a very practical approach to the question, simply asking what sort of definition of life should would be the best guide for their search. Traditionally, they've put a priority on life as we know it. All life on Earth uses DNA or RNA to encode genes; all life on Earth uses the same basic genetic code to translate genes into proteins; all life uses water as a solvent. One reason that NASA has put so much emphasis on looking for life on Mars is that it's plausible that life as we know it might have existed on Mars back when the planet was warm and watery. And besides, how are we supposed to look for a form of life we've never seen before?

But in 2007 a National Academies of Science panel urged that we take a broader view of life, so that we wouldn't miss the dollar bill in the couch. Other kinds of life were at least imaginable–such as organisms that used different backbones for their genes, or perhaps might swim through liquid methane like fish swim in water. (Here's my write-up in the Times.) Some of the panelists–most notably, Steven Benner of the Foundation for Appllied Molecular Evolution–even endorsed a more radical notion. As I described in this feature for Discover, Benner and others speculate that maybe alien life is here on Earth.

A lot of evidence, for example, suggests that the first forms of life used RNA as both genes and enzymes. Later, double-stranded DNA evolved and DNA-based life wiped out RNA life. But perhaps RNA life still clings to existence in places where DNA-based life can't drive them extinct. Benner suggests tiny pores in rocks that would be too big for bacteria.

No one has found RNA life yet, nor have they found any all-natural alien on Earth. But as I point out in Microcosm, there are definitely aliens among us.

They're called E. coli.

Or, rather, they are laboratory stocks of E. coli that scientists have transformed so that they use new genetic codes or even use new nucleotides, the "letters" of DNA. No life that we know of has ever lived this way.

NASA's press conference concerns another nearly-alien kind of life on our own planet. NASA has sponsored many expeditions to the toughest places on Earth for life to survive, from glaciers to deserts to acid-drenched mines. One of these expeditions was to Mono Lake, a practically toxic body of water. It's very salty, very alkaline, and is steeped in arsenic. The "weird life" report singled out arsenic-based life as one topic worth investigating, so Felisa Wolfe-Simon of the NASA Astrobiology Institute and her colleagues isolated a strain of bacteria and brought it back to the lab to study its growth.

As I mentioned earlier, life as we know it uses DNA for its genes (except for some viruses that use RNA). DNA has a backbone made of two alternating units: sugar and phosphate. Phosphate is one phosphorus atom and four oxygen atoms. It just so happens that arsenic–despite being a poison–has a lot of chemical properties similar to phosophorus. In fact, one arsenic atom and four oxygen atoms combine to form a molecule called aresenate that behaves a lot like phosophate.

Wolfe-Simon and her colleagues reared the bacteria in their lab, initially feeding them a typical diet of essential nutrients, including phosphate. But then they gradually reduced the phosphate in their diet and replaced it with arsenate. Before long, as they report today in Science, the bacteria were growing nicely on an all-arsenate diet, without a speck of phosophate. The scientists then probed the DNA of the bacteria and concluded that they were sticking the arsenate into the DNA in place of phosphate. Phosphate is also vital for other molecules, such as proteins, and the scientists found arsenate in them as well. In other words–arsenic-based life.

Or…maybe not. In Science, reporter Elizabeth Pennisi writes that some scientists are skeptical, seeing other explanations for the results. One possibile alternative is that the bacteria are actually stuffing away the arsenic in shielded bubbles in huge amounts.

I got in touch with Benner, who also proved to be a skeptic. "I do not see any simple explanation for the reported results that is broadly consistent with other information well known to chemistry," he says. He pointed out that phosphate compounds are incredibly durable in water, but arsenate compounds fall apart quickly. It was possible that arsenate was being stabilized by yet another molecule, but that was just speculation. Benner didn't dismiss the experiment out of hand, though, saying that it would be straightforward to do more tests on the alleged arsenic-DNA molecules to see if that's what they really are. "The result will have sweeping consequences," he said.

If Wolfe-Simon can satisfy the critics, this will be research to watch. The Mono Lake bacteria probably don't actually exist in an arsenic-based form in nature, since they grow much faster on phosophorus. They're aliens, but aliens in the same way unnatural E. coli are, thanks to our intervention. But Wolf-Salmon's results suggest that life based on arsenic is at least possible. It might even exist naturally in places on Earth where arsenic levels are very high and phosphorus is very scarce.

Such a discovery would indeed be huge news–although not as huge as a similar discovery on another planet. For now, we will have to content ourselves with arsenic-laced dreams.

(PS: You should be able to watch the press conference live starting at 2pm Thursday 12/2 here.)

Reference: Wolfe-Simon et al, "A Bacterium That Can Grow by Using Arsenic Instead of Phosphorus" Science, 10.1126/science.1197258

[Image of Mono Lake by .Bala via Flickr, under Creative Commons License]

[Update: Fixed Wolfe-Simon's name. Now I am left with images of wolf salmon roaming in packs.]

[Update: Fellow Discover bloggers Ed Yong and Phil Plait are on the case, too.]

November 29, 2010

The clouds are alive! My new podcast on aerobiology

On my latest podcast, I explore the invisible ocean of life through which we swim every day: the air. I talk to Jessica Green of the University of Oregon about life in the clouds, in our houses, and everywhere in between. Gee-whiz science at its finest. Check it out.

On my latest podcast, I explore the invisible ocean of life through which we swim every day: the air. I talk to Jessica Green of the University of Oregon about life in the clouds, in our houses, and everywhere in between. Gee-whiz science at its finest. Check it out.

November 22, 2010

The empire of viruses: my story in tomorrow's New York Times

Recently I paid a visit to a place where the world's most mysterious viruses go to find a name. The result was my profile of Ian Lipkin of Columbia University for tomorrow's New York Times. I first started thinking about this story when I heard Lipkin give a lecture about his work identifying unknown viruses this spring. And when I read this review of Lipkin's, entitled simply, "Microbe Hunting," I knew it was time to get cracking.

Recently I paid a visit to a place where the world's most mysterious viruses go to find a name. The result was my profile of Ian Lipkin of Columbia University for tomorrow's New York Times. I first started thinking about this story when I heard Lipkin give a lecture about his work identifying unknown viruses this spring. And when I read this review of Lipkin's, entitled simply, "Microbe Hunting," I knew it was time to get cracking.

One thing I didn't have room for is the fact that Lipkin has gone all Hollywood. By which I mean that he's helping Steven Soderbergh on a new movie on a virus outbreak called Contagion, starring Mate Damon Kate Winslet and other big stars. Lipkin seems pretty stoked about the movie, which is slated for 2011, so I'll definitely be keeping an eye out for it.

November 20, 2010

The traffic jam in your head (now with Slashdot goodness)

[image error]My new brain column for Discover is online, and it's about one of the weirder failings of our mind: the way our thoughts can get stuck in a traffic jam. When we are required to do two things in quick succession–like answer a cell phone and hit the brakes–our brains freeze up for an instant. Researchers have known about this so-called psychological refractory period for decades, but they're still trying to figure out how, and why, it happens. As I explain in my column, this inner weakness may actually reveal an inner strength. Check it out. (And thanks to Slashdot for the tsunami of link love.)

November 18, 2010

Your inner viruses: the trickle becomes the flood

Scientists have known for decades that the genomes of animals can sometimes harbor DNA from the viruses that have infected them. When I first learned of this fact some years ago, it blew my mind. The notion that any animal could be a little bit viral blurred nature's boundaries.

Scientists have known for decades that the genomes of animals can sometimes harbor DNA from the viruses that have infected them. When I first learned of this fact some years ago, it blew my mind. The notion that any animal could be a little bit viral blurred nature's boundaries.

The viruses that scientists discovered in host genomes were of a particular sort, known as endogenous retroviruses. Retroviruses, which HIV and a number of viruses that can trigger cancer, have to insert their genetic material into their host's genome in order to reproduce. The cell reads their genetic instructions along with its own, and then builds new viruses. It made a certain intuitive sense that retroviruses might sometimes get trapped in their host genomes, to be passed down from one generation to the next.

The first endogenous retroviruses scientists identified were still relatively functional. Under certain circumstances, their genes could still give rise to new viruses that could break out of their host cell. But gradually, scientists identified more and more fossil viruses, which had mutated so much that they could no longer reproduce. As I wrote in the New York Times in 2006, scientists have even figured out how to resurrect these fossil viruses from the human genome.

That would have been weird enough. But nature is generous with its weirdness. As I wrote in the Times earlier this year, scientists have started finding viral stretches of DNA in our genomes that are not retroviruses. In that article, I focused on the discovery of genes from bornaviruses, which just park themselves next to our DNA, rather than inserting their genes into our own.

New kinds of endogenous viruses keep turning up as scientists looked closer. Today in the journal PLOS Genetics, Aris Katzourakis of the University of Oxford and Robert Gifford of New York University offer a particularly startling survey of the viral world within. Rather than searching for one particular kind of virus, they hunted for a wide range of them. Their collection reflected all the different ways that viruses can replicate inside mammal cells. They then hunted for the sequences of these viruses in the genomes of 44 mammal species, plus a handful of birds and invertebrates. The scientists struck viral gold. Every major group of viruses turned up in the host genomes.

In most cases, the viruses infected their own host. But the scientists also found mammal viruses integrated into the genomes of ticks and mosquitoes–perhaps as a result of their feeding on virus-infected mammal blood. In many cases, viruses slipped into their host genomes a long, long time ago. The scientists discovered segments of bornavirus present not just in humans, but in monkeys from the Old World and New World. We share a common ancestor with monkeys that lived some 54 million years ago. What's more, one of these bornavirus segments is very similar in many of its hosts today. That uniformity suggests that it has taken on a useful function in our own bodies. Scientists have already found evidence that endogenous viruses can help build placentas and fight off other viruses; now bornaviruses can be added to the list.

This is one of those exploding fields that is a joy to follow. I'm glad that this new paper came out before I had to turn in my proofs for my next book, called A Planet of Viruses, which will be coming out in May. But I'm sure that the catalog of inner viruses will be growing a lot longer in years to come.

[Update: Ed Yong is also infected with curiosity.]

November 16, 2010

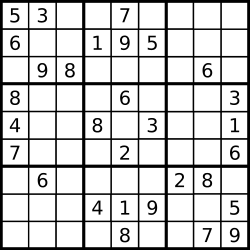

Is there nothing E. coli cannot do? The Sudoku edition

Every now and then I take a moment at the Loom to marvel anew at the sophistication of a certain microbe. Today, I direct your attention to a report in New Scientist on E. coli that has been engineered to solve Sudoku puzzles. Frank Swain, the author, makes a good point: if E. coli is allowed to spread out the task among millions of individual microbes, it can tackle bigger problems. Let's just hope that all the E. coli in our guts don't figure this out on their own…

Every now and then I take a moment at the Loom to marvel anew at the sophistication of a certain microbe. Today, I direct your attention to a report in New Scientist on E. coli that has been engineered to solve Sudoku puzzles. Frank Swain, the author, makes a good point: if E. coli is allowed to spread out the task among millions of individual microbes, it can tackle bigger problems. Let's just hope that all the E. coli in our guts don't figure this out on their own…

November 15, 2010

Evolution and the citizen: Your thoughts?

I'm preparing for my first trip to New Orleans. The occasion is the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America. Steven Austad, a University of Texas biologist, asked me to come give a talk in a session he's organized next Monday. Austad studies the evolution of aging in the hopes of finding ways of slowing the aging process. (I wrote about him in 2007 in the sadly defunct Best Life magazine–read the article here or here.) In the face of an anti-evolution education bill passed by the Louisiana legislature, Austad decided to use his trip to the state next week to organize a session on the important of a good evolution education.

My task is to discuss "how understanding evolution allows Americans citizens to formulate more informed decisions about societally important matters." I like this assignment, because it's an interesting twist on the standard question about the value of evolutionary biology. Typical answers to that question include the cosmic–how it helps us see our place in the history of the universe–and the practical–how it can help in our search for better health and happiness. (See here, for example.)

The question I'm addressing is a bit different. How does a good understanding of evolution better prepare us to make decisions as citizens?

I've got a few ideas of my own, but this seems like a good question to throw open for discussion. If I crib any of your suggestions for my talk, I will thank you profusely when I deliver it. You'll be able to check for yourself next week, when I'll post a recording with slides.

So…thoughts?

Update: The stars align! A couple hours after I posted this request, Ed Yong posted his excellent write-up of evolutionary trees in the courtrooms.