Rod Dreher's Blog, page 610

February 26, 2016

Caleb Stegall Prophesied The Trumpening

No, really. Back in 2006, I commissioned Caleb to write a piece for the Dallas Morning News about prospects for American populism. Here’s a link to the piece. In it, he describes a country ripe for a new kind of populism, and offers a model. Excerpt:

There’s an irony inherent in a system like our own that identifies the individual as the fundamental unit of political, social and economic order. Because it shears the individual of the republican virtues cultivated within communities of tradition in the name of empowering him, it actually makes the individual subject to tyranny. Limitless emancipation in the name of progress is, it turns out, the final and most binding mechanism of control.

When the oldest sources of order – which are at root religious – are abandoned along with their traditions and taboos, the resulting void of meaning is by necessity filled with some ideology promising one form or another of perfect happiness in the here and now. And these systems of self-salvation creep not toward liberation, but toward total control.

Populism in its progressive form is not immune from this utopian yearning, which must always end in disaster. So our neopopulist moment ought to be approached with sober awareness that an angry mob is probably worse than a corrupt bureaucrat. The same bureaucrat who has harnessed the anger of the mob with progressive dreams is far more terrible than both.

What is called for is an anti-progressive populism; an anti-movement movement; a return to what is near, known and particular. What is called for is what I think of as regional populism. Its first political task will be to rediscover the ways citizens of the old American republic used to think and talk.

Then:

It may be too late, things too far gone, for the kind of Anti-Federalist regional populism I am describing to become politically viable in our day. If so, we will likely be tossed between the tyranny of a militantly nationalist populism and the stifling bureaucratic rule of a progressively universalizing liberalism. Neither is a welcome alternative.

Read the whole thing. He’s just described the Trump/Clinton election.

As you know, I’m in the mountains of Umbria this week, and far from the American political scene. But reading Google news and my Twitter feed, Trump’s shtick is getting awfully stale.

February 25, 2016

Rubio Beats Up Trump

The debate was in the middle of the night here in Italy, so I missed it live, but if this clip is any indication of how it turned out, Rubio beat the tar out of Trump. McKay Coppins:

While Cruz and Trump traded jabs as well, it was Rubio who landed the strongest blows of the night. During a round of questions about how to replace Obamacare, Rubio repeatedly — and aggressively — challenged the billionaire to provide detail to his health care proposal. The best Trump could muster under pressure was variations on, “We’re going to have many different plans.”

And in one of the most memorable attacks of the night, Rubio dismissed his business success as a mere byproduct of a rich father.

“If he hadn’t inherited $200 million, you know where Donald Trump would be right now? Selling watches in Manhattan,” he said.

The line drew loud applause in the debate hall and blew up Twitter, but it almost certainly got under Trump’s skin more than any other unkind word said about him Thursday night. The real test for Rubio will be whether he can accelerate his campaign’s momentum in Super Tuesday states amid a barrage of insults from The Donald in coming days.

In that clip above, Trump came across like a windbag-turned-punching-bag. Is that how it went? Tell me, you who watched the debate.

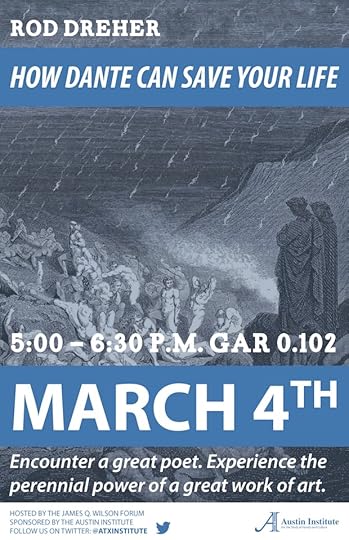

Next Week In Austin

It’s a great story. Trust me. And a good one for Lent. Go here and register to win a free copy of How Dante Can Save Your Life.

Norcia Diary

I don’t ask, “Is Italy a great country?” Everybody knows that. It produced Dante, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Chef Boy-Ar-Dee. The question before us now is this one: Is Italy the greatest country?

I ask because late yesterday afternoon, I was at Caffe Tancredi, a tiny bar off the piazza here in Norcia, having a Birra Nursia, when the young woman standing next to me struck up a conversation in English.

“You must come to my pig farm,” she said. Peeg farm. This bore investigation.

Her name was Valentina, and she was having coffee at the bar with her Mamma. “She doesn’t speak English,” said Valentina. “She speaks ham. Ha ha!”

Mamma gave me the thumbs up. I liked these people at once.

Valentina’s English wasn’t great, and my Italian, like Mamma’s inglese, is non-existent. But she and Mamma managed to communicate that their pigs had one a global competition for best prosciutto, or something like it, and that The Guardian had come all the way from London to write a story about them.

“You come to us,” Valentina said. “Here’s the number. My father will pick you up.”

It was very nice, but I’m a busy man, here writing a book about monks. But after I finished my beer, I went for a walk around this village, saying my prayer rope, and it occurred to me that Norcia is known all over Italy for the quality of its cured meats. If I had been in Burgundy, and had been invited by a family to visit its vineyard, would I say no? Of course not.

What do you know, but an hour later, walking around the piazza with my prayer rope in hand, I ran into Mamma and Pappa. His name was Giuseppe, and he apologized for speaking no English. I returned the apology for my lack of Italian. We shook hands warmly, and Mamma said over and over again that I must come to the peeg farm. I promised her I would. They kindly stood for a selfie. Great people!

I had dinner at a restaurant called Il Cenacole, which serves pork — everybody here serves pork, and lots of it — from its own herd. The server told me that they’re part of a movement to bring back a heritage breed that is a hybrid with cinghiale, the wild boar native to this area. I had pork, but I started with a pasta with black truffles, which are also native to this area. It was delicious, though the server, Michaela, told me that this was a bad year for truffles in these mountains. It wasn’t cold enough, she said. She brought out the last of the winter’s black truffles, small dark fungal lumps the color of chocolate, and presented them to me like holy relics.

I went home full of peeg, pasta, and truffles, and settled down to work. But again, I fell quickly asleep, and slept for, get this, ten hours. This is very unusual for me, but I realized this morning when I woke up way past the time to call the peeg farm that Norcia is having the effect of unwinding me. I had not realized how tightly wound and stressed I have been until arriving here, and entering into the stillness of life in this mountain village. My wi-fi access is unreliable, so I can’t check the latest news every few minutes. It is frustrating, but also a blessing.

After getting dressed late this morning, I lumbered across the piazza to Caffe Tancredi for my morning cappuccino. The barista was busy making his special chocolate cappuccino creation for some women at the other end of the bar. I’m not a fan of chocolate, but he was so proud of it I had to taste his specialty. And it was, of course, out of this world. He was smartly dressed, with a bow tie — this, in a bar the size of a big closet. The pride this man took in his work was evident. I finished my coffee, then walked back across the piazza to church.

The cowled monks were in the middle of the day’s mass. I stood in the rear of the church, praying my prayer rope as they chanted the traditional Latin liturgy for a small congregation. Do you want to hear the kind of thing I was hearing this morning? The monks have a recent chart-topping album of their chants. If you haven’t yet seen it, take a look at the 60 Minutes report on the monks, this monastery, and their chants. These men are real. This is a thing not from over a thousand years ago, but from today. This day. I mean, it is from over a thousand years ago, but it’s right here, right now, too.

There was such a purity to the Gregorian chanting; it made me think of ivory pouring down like fresh milk. That is, there was something eternal and transcendent about it — these sounds could have been transmitted whole from the early medieval period — but also viscerally present. It was such a strange and wonderful feeling, a moment utterly out of time. The celebrant raised the Host high, facing the altar (they say the traditional mass here), and the feeling of eternity was, paradoxically, both modest and overwhelming. I deeply wished that Catholics could experience this, and see what is possible within their tradition, how beautiful it is, and how elevating.

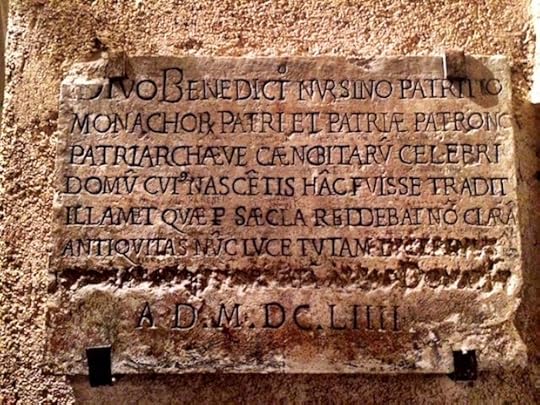

After the mass, the crypt below the church opened, and I went down to pray. The crypt includes the original church built here, which had first been the Roman administrative building when Norcia was Nursia, a Roman town. The father of Sts. Benedict and Scholastica, twins born here in 480, was the Roman official, and lived with his family in this building. In this space, Romans of Nursia gathered to hear the decisions of Benedict’s father. Benedict and Scholastica would have been born in this edifice.

I interviewed a young American monk yesterday, and he said that after being here a couple of years, when he goes back home, everything about America feels so transient and insubstantial. I didn’t take him as being critical, but simply observing how living in such an old place refocuses one. As I walked around under the vaulted ceiling of the crypt, I tried to imagine the Romans who trod these same stones — including the boy Benedict. To the left of the main altar is a side altar in an apse, dedicated to Benedict and Scholastica (see the photo above). It traditionally marks the site of their birth. There is a new icon of the twins on the altar, and above, the remains of a 14th-century fresco commemorating their birth.

I prostrated myself, then took a seat on the bench and continued my daily prayer rule. There in the crypt, the silence is as total as it is possible to achieve in Norcia. What sounds reach there are faint and faraway, as long as pilgrims in squeaky sneakers stay upstairs. At first, the quiet is unnerving. Why is that? It’s because one is uncomfortable being alone with one’s thoughts. Hadn’t one of the monks told me the day before, in an interview, that the great silence of the monastery makes it hard to hide from one’s true self?

If you asked me to pray for your intentions here, I did so this morning in the crypt, and lit a candle for you and yours. A reader wrote last night to say that her dear cousin had died. She is a Protestant, but asked me to remember her cousin in prayer here. I did so, and put that intention in written form, so the monks will be praying for her too. I dunno, it felt like the communion of saints down there in the crypt, with me, an Orthodox Christian, praying for a Protestant Christian, in this ancient church inhabited by Roman Catholics. All our differences seemed far away down there underground with St. Benedict and his sister.

Today is the Feast of St. Matthias for Catholics, and I was encouraged to come to lunch. Given the feast, the monks were going to serve the festal beer they produce, the dark version of Birra Nursia. I walked in and took my usual seat at the long table, and service began. It was pasta, salad, fish, and fruit with whipped cream. The beer was extraordinarily good, genuinely some of the best I’ve had in ages. Did you know you can buy it in the US now? Go to the website for ordering information.

Listening to Brother Ignatius read aloud from the platform during lunch, I rejoiced inside over the warm welcome I have received here. They really do honor St. Benedict’s Rule, which commands the brothers to receive guests as Christ. I thought about my friend the Reformed theologian James K.A. Smith, whose great new book I’m reading in an advance reader’s copy now, and how deeply and profoundly at home he would feel here among these Catholic brothers in Christ. We have a lot to regret about these post-Christian times, but one blessing of them is that we Christians from rival traditions can let go of our historical divisions, and enjoy the fellowship of each other’s company. I was born Protestant, became a Catholic, left the Catholic church a broken man, and entered into Orthodoxy. I am grateful for Orthodoxy, and God willing, will remain Orthodox all my life. But these men, these monks, are my brothers in Christ, and I will learn from them what I can about serving Him.

It’s hard to think about going down the mountain, back into the frenzy of the world. My hope with the Benedict Option book is to bring some of the peace and tranquility and timelessness of the monastery in St. Benedict’s village to readers all over my country. We cannot all be here in the monastery, but we can hope to have the monastery within our hearts and homes. I am convinced that what is happening here, now, this day, in Norcia, within these monastery walls, is more important for our future than anything happening in the US presidential race. My task is to help you readers see this too.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

Hey Rod, when I read today your comment “It’s hard to think about going down the mountain, back into the frenzy of the world,” I thought: Wait, haven’t I read something like that quite recently? And then it hit me — I man describing what happened after he made a retreat at a monastery in Kentucky:

Back in the world, I felt like a man who had come down from the rare atmosphere of a very high mountain. When I got to Louisville, I had already been up for four hours or so, and my day was getting on towards its noon, so to speak, but I found that everybody else was just getting up and having breakfast and going to work. And how strange it was to see people walking around as if they had something important to do, running after busses, reading the newspapers, lighting cigarettes.

How futile all their haste and anxiety seemed.

My heart sank within me. I thought: “What am I getting into? Is this the sort of a thing I myself have been living in all these years?”

At a street corner, I happened to look up and caught sight of an electric sign, on top of a two-storey building. It read: “Clown Cigarettes.”

I turned and fled from the alien and lunatic street, and found my way into the nearby cathedral, and knelt, and prayed, and did the Stations of the Cross.

Afraid of the spiritual pressure in that monastery? Was that what I had said the other day? How I longed to be back there now: everything here, in the world outside, was insipid and slightly insane. There was only one place I knew of where there was any true order.

— Thomas Merton, The Seven Storey Mountain (p. 364).

Wow.

Yes.

February 24, 2016

La. Republican Rends Partisan Garment

“The state budget, what a mess,” Normand said. “Bobby Jindal was a better cult leader than Jim Jones. We drank the elixir for eight years. We remained in a conscious state. We walked to the edge of the cliff and we jumped off and he watched us.

“And guess what? Unlike Jim Jones, he did not swallow the poison. What a shame.”

Normand accused Jindal of “trying to rewrite history” since leaving office, attempting to deflect responsibility for budget gaps estimated at $943 million between now and the June 30 end of the fiscal year. The state is also estimated to face a $2 billion shortfall in the 2016-17 budget year.

“He’s trying to get everybody to believe that he did a phenomenal job. We have to just say no,” Normand said. “I’m a Republican. But I’m not a hypocrite. … We did this to ourselves, myself included, because I endorsed that idiot. And now we’re going to try to play partisan politics as it relates to this.”

He said GOP ideology has been a catastrophe for the state. More:

“We’re facing enough challenges today,” Normand said. “We do not need to face the stupidity of our leadership as it relates to how we’re going to balance this budget, and talking about silly issues, because we’re worried about what Grover Norquist thinks. To hell with Grover Norquist. I don’t care about Grover Norquist. Give me a break.”

Whole thing here. Ruh-roh. First Donald Trump starts blaspheming against Republican orthodoxy, now this. Interesting to consider whether or not the Grand Inquisitors (Limbaugh, Levin, et alia) have any power left to smite rebellious Republicans.

Big Business Is Not Our Friend

A reader writes:

Hope you are enjoying Italy and the beer!

Meanwhile here in the good old USA, I just received a clothing catalog from Lands End. OK – good so far, nice clothes, modest, feminine – wait – what the ! A three page spread in their latest catalog on Gloria Steinem “Legend”.

Has this country come unhinged? I can’t even shop for clothes without being exposed to agitprop? Worse – the catalog is planning on donating proceeds from its sale to Gloria. “For every buyer who orders an ERA Coalition logo monogram on one of its items, Land’s End will donate $3 to the coalition’s Fund for Women’s Equality, Inc., according to the website. The campaign – “in honor of Gloria’s work” – is running now through Jan. 31, 2017, the website states.”

Now, I’m just a mom looking for a bathing suit that will cover my middle aged lumps but for frig’s sake. Now I can’t order them from Lands End. So – yes, a little pain and suffering having to switch to LL Bean or Eddie Bauer. Not a big deal – but as I have been thinking about it – damn it, I am withdrawing consent to be governed by corporate America. We already avoid eating processed foods, buy most stuff locally, but even more so – I am not buying clothing unless its from a place that doesn’t have some kind of activist agenda. We have to buy furniture soon – guess what? Will be buying used or locally made by someone that is not going to use my money to work against our values.

Good grief. I’m so frustrated by this – it just seems so crazy. Can you imagine ever getting a Sears catalog in the mail in the 70s with a spread lauding an partisan activist?

What makes me nervous about this is that a) either they are clueless, b) they don’t give a crap about losing middle aged women like myself or c) they’ve run the numbers and I am a dying breed, i.e. the millennial demographic they are trying to attract (per their new CEO, who refuses to live in Wisconsin, by the way – flyover country – Federica Marchionni) *loves* Gloria Steinem. That is a truly frightening thought – and given that business is so data driven – there might be some merit to it.

Also – how many Lands End employees had to stuff their pro life views to keep their jobs when this lady took the helm? I feel badly for them…

Stupid Lands End. As I type this, I am wearing a sweater from Lands End. My family spends a lot with them. I will take my custom elsewhere in the future. What is the point of praising Gloria Steinem, for heaven’s sake? Are Federica Marchionni and the people who surround her so out of touch that they think most Americans admire the aging pro-abortion activist? We see here another instance of Big Business taking sides in the culture war, in a big way.

Guess what, ye Reaganauts, and those who still believe that the 1980s model of conservatism is relative to today: Big Business Is Not Our Friend.

Again and again I say unto you, my brethren and sistren: this kind of thing is aiding and abetting the Trumpening. A lot of people are sick and tired of it, and have no way to express their frustration politically. Trump is the pushback.

UPDATE: The dedication to Gloria Steinem’s 2015 memoir reads as follows:

This book is dedicated to Dr. John Sharpe of London who, in 1957, a decade before physicians in England could legally perform an abortion for any reason other than the health of the woman, took the considerable risk of referring for an abortion a 22-year-old American on her way to India. Knowing only that she had broken an engagement at home to seek an unknown fate, he said, you must promise me two things. First, you will not tell anyone my name. Second, you will do what you want to do with your life. Dear Dr. Sharpe, I believe you, who knew the law was unjust, would not mind if I say this so long after your death. I’ve done the best I could with my life. This book is for you.

Lands End has reportedly scrubbed all references to Steinem from its website. I am told there’s no small degree of panic there. They really did not see this coming. They have NO IDEA AT ALL of the country they live in, and what people who pay their salaries hold sacred.

The Culture Of Trumpening

It is a gift that I don’t have to pay as much attention to American politics this week as I have been doing. In case you haven’t been reading my other posts, I am visiting a monastery in the mountains of Umbria this week, doing some reporting for my Benedict Option book. The only real American political story now is Trump, and I wanted to draw your attention to a couple of pieces that help explain his appeal in terms of culture war.

The first is by Reason magazine’s Robby Soave, who is most assuredly not a Trump fan. He focuses here on how the Trumpening may be in part a reaction to political correctness. Consider:

Surely, there’s no place less likely to become the site of an impromptu Trump rally than a college campus. And yet, at a recent Rutgers University event, throngs of students erupted into cheers of “Trump! Trump! Trump!”

Would many of them cast a vote for Trump in a GOP primary? Probably not. For these students, Trump is not the leader of a political movement, but rather, a countercultural icon. To chant his name is to strike a blow against the ruling class on campus—the czars of political correctness—who are every bit as imperious and loathsome to them as the D.C.-GOP establishment is to the working class folks who see Trump as their champion.

That might not be much comfort for the numerous people on the right and left—myself and most of my colleagues included—who consider Trump a narcissistic, fearmongering authoritarian peddling a destructive, fascistic policy agenda. But what if his supporters aren’t actually applauding his agenda: what if they’re merely applauding the audaciousness of his performance?

“Trump’s becoming an icon of irreverent resistance to political correctness,” Milo Yiannopoulos, an editor at Breitbart, told me. “It’s why people like him.”

Even some people on campus.

He quotes provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos saying that nobody votes for Trump because they agree with his policy prescriptions. I think that’s mostly true. Rather, it’s about making a cultural statement. The fact that Trump doesn’t care about p.c. pieties is the source of much of his strength. Soave talks about the ridiculous campus culture that has emerged, including a recent story about how Brown University students have talked themselves into psychological meltdowns because of their activism. Trump voters — this is me talking, not Soave — know that their guy would go in there and give those privileged Ivy League whiners a swift kick in the butt.

Here’s Soave:

Given all that, it’s no wonder non-leftists think media corporations are against them. Media members are against them, too. And so are colleges.

Cheering on the likes of Trump and Yiannopoulos might just be one way for them to cope with that perceived reality. Trump’s naysayers claim—with good reason—that his candidacy is a disaster for the Republican Party: his election to the presidency would destroy the country. But that’s a selling point for his supporters—not because they love destruction, but because they’re suffering under the status quo, too. At least with Trump, they can enjoy the show and collect some small measure of vengeance against their PC overlords.

Read the whole thing. It is by no means unreasonable to conclude that the Trumpening is the only means possible to push back against the cultural insanity the overclass (in media, in academia, in big business, in government) is impressing on an unwilling people. Media people and academics think Black Lives Matter, with its emotionally hysterical identity politics and illiberalism, is a great thing. The Trump people are in many ways doing exactly the same thing, and are denounced for it. They don’t care. They’re sick of the double standard.

Along those same lines, Ben Domenech — also no fan of Trump’s — explains why to the very great shock and disgust of many Evangelical leaders, Evangelical Christians are breaking for Trump. Excerpt:

That’s why Trump has been able to peel away so many evangelicals as his supporters, despite being an unchurched secularist with three wives who couldn’t tell a communion plate from an offering basket. It is because of the increasingly large portion of evangelicals who believe the culture wars are over, and they lost.

If you’re a conservative who thinks the culture wars are over (they’re never really over, of course), then you are a lot more open to the idea of a unprincipled blowhard who promises he’s got your back on political correctness. From the perspective of the southern evangelicals I’ve spoken to in South Carolina, they don’t have any qualms about admitting that Trump is not a good Christian. They have no illusions about his unbelief. The difference is that while they believe Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio would be one more round of good soldiers for their cause [Emphasis mine — RD], they think Donald Trump would be a tank.

Evangelicals tried for years to fight for the culture—to win the argument for their traditional views regarding marriage, family, and the value of human life. Now they want to fight on different ground: political correctness. And since Trump is the king of that—an ally who isn’t Jesus-y but says he’s with the Jesus people—he can tear off a third of that evangelical electorate without moderating any of his secularism.

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but I think Domenech is onto something real. Trump is not a religious man, and as a New Yorker friend tells me, therefore cannot be counted on to understand religious people and the need for religious liberty. That may well be true — in fact, I suspect it is true. But if Domenech is right, Evangelicals (and Catholic conservatives) may have concluded that by now, the deck is stacked against them, and the only thing standing between them and liberal authoritarianism that is going to demolish their (our) institutions is a combative SOB who doesn’t care what Enlightened Opinion thinks of him. They may be wrong, but it is by no means an unreasonable conclusion. In fact, it could be an eminently pragmatic one. The institutional Republican Party will do whatever its donors tell it to do on religious liberty and gay rights. The Indiana RFRA fight proved that. Trump takes no money from those donors. It’s not hard to put two and two together.

Again — and hear me, because a lot of people who read this do not — I am not suggesting that one ought to vote for (or against) Donald Trump. I am only trying to do what so many people on the left and the right seem to be incapable of doing: understanding why he makes sense to folks.

In Norcia, At Last

After sung vespers, and just before going in to dinner last night at the Benedictine monastery in Norcia, a young man stopped me in the space outside the refectory, extended his hand, and said, “Rod, it’s Justin.”

I didn’t remember him from last time.

“You put me on your blog,” he said. Suddenly I remembered: it was in this post that I included a video pitch from Justin Leedy, who was trying to raise $45,000 to pay off his student debt so he could come to Norcia and pursue a vocation. And there he was, right in front of me.

“Did it work?” I asked tentatively.

“It worked!” he said. “I’m here.”

I crossed myself and said a quick prayer of thanksgiving. Readers of this blog who contributed to Justin’s campaign, thank you. There is a young man preparing to enter the monastery here in Norcia because of your generosity.

Father Cassian, the prior, welcomed me in the traditional Benedictine manner, by pouring water over my hands into a basin, and then we went in to dinner. Taking my place at a long table, I turned to the tall, bearded layman on my right to shake hands and greet him, but he smiled and shook his head. No talking! Right. After initial prayers, Brother Ignatius, the guestmaster, ascended the stairs to a platform overlooking the refectory, and began to read from the day’s selection, the memoirs of Father Louis Bouyer.

Some monks served us course after course, silently but efficiently. We had a simple pasta, then vegetables, then fish, followed by a bit of yogurt and fruit. The last time I was here, the iconographic frescoes were coming along nicely. Here’s an image from that time, in the autumn of 2014:

Since then, much more has been added. The iconographic style is essentially Byzantine, but with a bit more humanity and warmth in the faces — a distinctly Western touch, as is appropriate. There is, I’ve noticed since arriving, a distinct appreciation here for Orthodox spirituality, however. An icon of the Dormition hangs over the bed in my monastery-provided room, and an icon of the Last Supper presides over the dining table in the apartment, as in Orthodox homes. They sell Orthodox prayer ropes and icons in the monastery gift shop, and I suppose it goes without saying that the monks here could not possibly be more welcoming to me, an Orthodox Christian.

After dinner, the monks stood to chant more prayers, then filed silently out to their evening. I went back to my apartment adjacent to the monastery, and passed a beautiful site: a “norcineria,” which is to say a shop that sells cured pork and boar in a hundred different ways. That’s what Norcia is known for, and never was I happier that we Orthodox still are not in Lent. I took a photo of it, but am having a lot of trouble transferring photos from my iPhone to my computer over wifi, so I can’t show it to you. I hope I can get this worked out this week. I apologize for having to head this post with an old image I’ve used several times before, from my last trip here, but I cannot yet get the new images to my computer.

It was only about 7pm, and I had intended to get work done, but the serenity of the atmosphere here in Norcia, as well as the calming rhythm of vespers, then dinner, worked on me hypnotically. I could barely keep my eyes open, and fell asleep before I could post anything to the blog. Turns out I needed the extra sleep to get my internal clock adjusted. I woke up this morning before daylight, praying as I rose out of sleep, and surrounded by a sense of peace so strong it almost felt luminous. Luminous. I’ve used that word a lot to describe this place, especially the countenances of the monks here. There is no better one, or if there is, I have yet to find it. I dressed, then went across the piazza to a tiny cafe, where I had cappuccino and a pistachio cornetto, and after paying, crossed the piazza again and entered the church. I had hoped to make my first visit to the crypt church, and pray before the altar that was once part of the childhood home of St. Benedict. But it was not yet open. I saw the tall man from dinner in a pew, kneeling in prayer.

I went back into the square and began circumnavigating the statue of St. Benedict, prayer rope in hand. It turns out that one revolution around the perimeter equals 25 Jesus Prayers. After the second turn, I saw the tall man leaving the church. We recognized each other, and I broke my pattern to walk over to say hello, and to apologize for disturbing his peace the night before at dinner. He looked to be in his early 30s, strong but extraordinarily beautiful. He had about him the same sense of peace as the monks.

“Fabrizio,” he said, extending his hand.

“Do you live here, or are you a pilgrim?”

“No, I work in the church.”

“Wait, you’re the iconographer!”

“Yes.”

Of course. My own godfather in Orthodoxy, the iconographer Vladimir Grigorenko, told me ages ago that a true iconographer must be a man of prayer. Fabrizio is such a man. If I had not seen him alone in the church praying, and also eating reverently and prayerfully in the refectory that he is decorating (that’s his work above), I still would have seen it in his face.

The world is very far away from this village in the Umbrian mountains. Late this morning, I begin my interviews with the monks, for the Benedict Option book. It is good — it is very good — to be here. The world needs what these men have. If I can communicate even a portion of it to readers, I will have been successful.

I mentioned to the guestmaster, Brother Ignatius, that I hoped to share their Christian wisdom with the world beyond Norcia, which so hungers for it. He sighed gently, and said, “We came to the monastery to escape the world, but the world keeps coming.”

He smiled. He knows that their prayer and their labor here in the monastery is for the sake of God, and in turn, of the world that God so loves. They have to live separately to a certain extent so they can kindle and intensify the God-given light within, but as their master St. Benedict instructed them, they welcome all others as Christ himself. And they teach all who incline their ears to listen. A Catholic professor wrote to the the other day, saying that these days in the post-Christian West, we have no need of arguments, but rather examples and stories. This is true. You cannot argue with the light in the faces of these men, and the deep peace in their eyes. And they are all so young!

February 22, 2016

View From Your Table

Rome, Italy

That’s Giuseppe Scalas, one of this blog’s favorite commenters, across the table from me. We had dinner tonight at Nonna Betta, a kosher restaurant in the old Jewish quarter. Though both of us are Christian, Giuseppe said the Jewish community has been a constant presence in Rome for over 2,000 years, and offers the most authentic Roman cuisine available today. The food was quite good. I’m eating pasta with artichokes, and Giuseppe is having rigatoni stuffed with sheep stomach. It’s actually not bad at all, though unusual. We had great food and even greater conversation. Walked around the Roman Forum and talked about the Church, the world, the Benedict Option, and our families. I have been unbelievably blessed by the people I’ve gotten to know through this blog.

On to Norcia tomorrow!

P.S. We also drank a toast to the memory of Antonin Scalia. “Uncle Nino,” Giuseppe called him. The great one was remembered tonight near the banks of the Tiber by two Christian men who revere him and who love to eat and drink.

What Jindal Did To Louisiana

The State of Louisiana is in an unprecedented fiscal crisis. Unprecedented, as in, it’s never been this bad before. Clancy DuBos, a New Orleans journalist, brings even worse news:

A common refrain among some lawmakers in Baton Rouge these days is that we should “look forward” and stop blaming former Gov. Bobby Jindal for Louisiana’s unprecedented fiscal crisis. If those lawmakers were to read the latest annual report by the Legislative Auditor, they’d change their tune.

According to the auditor, the Jindal Administration failed to timely file the vast majority of statutorily required reports on more than $1 billion a year in tax incentive giveaways for fiscal years 2013 and 2014.

“We found that three of the six agencies that administer tax incentives submitted reports as of March 23, 2015. As a result, the Legislature only received information on five of the 79 tax incentives administered by these agencies,” the auditor’s report states on page 17.

“In addition, of the 79 tax incentive reports agencies were required to submit to the Legislature by March 1, 2014, 70 (89%) either were not submitted or did not comply with all of the reporting requirements. According to the Department of Revenue’s Tax Exemption Budgets, the revenue loss from tax incentives claimed in fiscal years 2013 and 2014 for which agencies provided no information or did not comply with reporting requirements totaled approximately $1.1 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively.”

You read that correctly: $1.1 billion for fiscal year 2013 and $1.3 billion for fiscal year 2014.

There’s our budget deficit right there, folks.

More:

Jindal didn’t create this mess alone, however. Democrat as well as Republican legislators aided and abetted his malfeasance.

To be clear, those “tax incentives” are actually expenditures. If lawmakers opt to eliminate any of them, it won’t be a tax increase, it will be a reduction in spending. In that respect, we can all agree that Louisiana indeed has “a spending problem.” We’re spending way too much on corporate giveaways.

The auditor’s report summarizes 36 audits conducted in 2015 and identifies some $1.8 billion in questionable expenditures — the vast majority of them corporate tax incentives. That should outrage every Louisiana taxpayer.

Read the whole thing. The Louisiana-is-good-for-business story of the past eight years appears to have been largely built on the state paying corporations to do business here.

That “look forward, don’t blame” strategy is exactly what the national GOP wants us all to do regarding the Bush years, because it’s what they’ve been doing.

(Readers, please remember that I’m traveling today, and will not be able to approve comments in a timely way. I wrote this post on Sunday and scheduled it to run today.)

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers