Rod Dreher's Blog, page 609

March 2, 2016

View From Your Table

Norcia, Italy

This is my breakfast on Sunday morning in the refectory of the Monastery of St. Benedict, in Norcia. A bowl of milky coffee and a cookie (there was more available, but I was really sick with a sinus infection, and had no appetite). It makes me so happy to see this place again in this image.

(You might wonder why my glasses show up so often in these VFYTs I take. It’s because I’m near-sighted. I can’t see well in the distance, but up close, like when I’m taking a photo with my phone, I have to take my glasses off to see clearly. I tried bifocals, but hated them.)

San Benedetto del Tronto, Italy

Here’s lunch on Monday, at the restaurant Nautilus in the Italian city on the Adriatic coast. It was our pasta course: tagliatelle with seafood — clams, octopus, calamari, shrimp. Four of us shared this, plus a deliciously fizzy local white wine. After this, we had a big platter of lightly battered and fried seafood. I could have eaten a bucket of that octopus. Good times, good times…

What It Takes For Faith To Survive

Greetings from the sickbed. I had not realized how sick I had gotten in Italy until I returned home and was safe to crash. And crash I did. My doc has prescribed an antibiotic for this sinus infection. I’ve noticed that since my three-year bout with mono, my immune system is fragile, and even a cold often turns into something worse. So, my apologies for light posting. The real tragedy of all this, of course, is that when I’m in Austin this weekend, I will not be able to drink margaritas. Verily, we dwell in a vale of tears.

I wanted to say a little something more about faith in light of having watched Spotlight yesterday (read my impromptu essay from the airplane, which I posted yesterday; still can’t get over the fact that it’s possible now to have Internet on a transatlantic flight). I intend these words for all Christians — Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox — because I want you to benefit from the hard, hard lesson I learned. We are all going to face times of serious trial in the age upon us, and we should prepare ourselves. As a matter of fact, I think it was providential that I saw Spotlight after this grace-filled time in Italy, among inspiring Catholics. Let me explain.

As I have said before, as a Catholic, I was not prepared for the darkness of the child sex abuse scandal. Father Tom Doyle warned me early on, at the beginning, that if I proceeded down this path, I was going to come face to face with darkness that I could not even imagine. He told me this not to discourage me, but to warn me to prepare myself.

I thought I was prepared for anything. I really did — this, because I knew my faith. I knew it logically. I affirmed all its propositions, and strongly — that is, with an act of will. I thought that would protect me.

It did, for a while, but ultimately I quit believing in those ideals. No, that’s not quite right: I found myself unable to affirm those ideals. It was sheer exhaustion. This is not something that had ever happened to me with anything before, and I didn’t understand that it was possible. This is what can happen to you when your faith is too much inside your head.

The time I just spent in Italy helped me see this more clearly. For the monks, as for the lay Catholic Tipiloschi in San Benedetto del Tronto, the faith is not only propositional, but also a communal way of life. I trust that I don’t need to explain how this plays out for monks, but among the Tipiloschi, it is an extraordinary thing (see here for more details). Theirs is a lay Catholic community that is wholly committed to following Church teachings. They are thoroughly orthodox in their Catholicism, but they’re not angry about it. Do you hear me on that? They are not angry about it.

Living out their faith has a contemplative dimension, including formal group study of Scripture, the lives of the saints, and the Catechism. It also includes prayer, confession, spiritual direction, and, of course, frequent mass. They live out their faith by running a classical Christian school for the community’s children, as well as for others (they keep the tuition low so working people can afford it), and doing all kinds of charitable work in the community, especially involving their children in these things. And they meet often to feast, to garden, to sing, to play, and enjoy being with each other. The shocking thing for American eyes is how normal this all is for them. And in turn, I’m shocked that I’m shocked: this is how life in Christian community is supposed to be, but so rarely is.

I mentioned to Marco Sermarini, my host in SBT, earlier this week that if I had had in my Catholic life the monks of Norcia to give spiritual guidance and the Tipiloschi to live out the faith in daily life, things might have gone different with me and my Catholic faith. I had to make it clear that I am irrevocably committed to Orthodoxy, settled into Orthodoxy, and deeply grateful for the gift of it. But it bothers me that I didn’t enter Orthodoxy serenely, having concluded after passionless reflection that the case for Orthodox Christianity is stronger than the case for Roman Catholic Christianity — as if I were a judge deciding a case. No, I became Orthodox to save myself from drowning in anger, fear, and despair. I am very grateful to be Orthodox, and despite my love and admiration for the people I spent time with in Italy, I don’t have the slightest desire to return to Catholicism. I will walk along side my Catholic and Protestant brothers and sisters with joy and gratitude, but I’m on the right path, and am not leaving it. I hate to harp on that, but I just want to be clear here, because a lot of people, both Catholic and Orthodox, are confused about this.

To return to the point (a point that is valid for Orthodox and Protestant Christians as well as for Catholics): if there is no prayerful, contemplative dimension to your Christianity — because after all, the Christian life is about becoming fully united to Jesus Christ — then you run the risk of becoming like the tribal Catholics in Spotlight. That is, you risk becoming people who idolize the tribe (community) and its chieftains, even if it means sacrificing the ideals that the community is supposed to embody. If “being Catholic” (or Protestant, or Orthodox) requires you to turn a blind eye to the rape of children, or some other grave sin and crime, then you may as well adorn yourself with a millstone and jump off a cliff into the deep blue sea. Life in community is not enough in itself; in fact, as we see in Spotlight, it can lead you to make a false god of the community, such that you, in effect, murder the true God.

One of the reporters featured in the film says that he was raised Catholic, but quit practicing the faith. He always hoped to return to the faith one day, but now, given what he’s seen, he cannot bring himself to do it. It’s an excruciating scene, and actor Mark Ruffalo makes you feel the agony of lost hope. It must be said, though, that people who keep the faith at arm’s length like that, thinking that one day, one day, they’ll get it together and come back — they aren’t going to make it. I know a lot of Christians like that, people who are cultural Christians, with vague intentions of Getting Serious about it again. They will not last through what’s coming.

What does this have to do with the Benedict Option? I mentioned to Marco on Monday that I appreciated the sense of balance in the Rule of St. Benedict. He said he wasn’t sure what St. Benedict meant by “balance.” He said that the way he sees it, either you are with Jesus, or you aren’t. Either he is at the center of your life, and everything is organized around serving him, or, well, what’s the point? Either be radical, or don’t be at all. You can’t bracket your faith off from the rest of your life. To that I would add that in our post-Christian culture, either you will be radical in the sense Marco means, or you won’t be Christian, because it will cost too much, and be too difficult.

I think of the Tipiloschi as an ideal Benedict Option community because they appear to have achieved a good balance of active and contemplative life as lay Christians. You have to have both. And this is hard to do! But it’s necessary. As I go forward on the Ben Op book, I now have it more clear in my mind what kind of ideal I’m trying to lead people (including myself) towards. It was so, so good to see it in action, both in the monastery and among the lay people. It can be done; I know this because it is being done right now. Watching Spotlight on the flight back, and having to revisit in some sense the reason why I lost my Catholic faith, and might have lost my Christianity entirely had things continued, gave me deeper insight into the challenge we all face, and will face. Believe me, you do not want to discover your own failures as a Christian when you are put to a hard test. Now is the time to prepare yourself and your community for the difficult future ahead.

Obviously I don’t know each of your readers personally, but I’d say it’s a pretty good guess that many of you are like I was in the year 2000, when Father Doyle warned me about the malign power of the darkness I was just starting to explore. I thought I could withstand anything. I was prideful in my faith, and I was smashed by that trial. Whatever your faith tradition, my warning to you is: don’t take anything for granted. You don’t know what’s coming. You think you know, but you don’t. You think you can imagine from where the attack might come, but you are almost certainly deceiving yourself. Learn from my mistakes.

March 1, 2016

Homeward Bound

The Marche, in Italy (Photo by Rod Dreher)

Many years ago, when I was in college, or maybe had just graduated, I was reading the latest issue of Vanity Fair on a flight to Europe, and read Bill Buckley’s answers to the Proust Questionnaire, a fun feature the magazine used to run (does it still? I haven’t read VF since Dominick Dunne died). Bill was asked, “What is your favorite journey?” And he answered: “Home.”

I remember thinking at the time — seriously, I do — will I ever get to the point in my life when I could give that answer? It seemed impossible. I could have thought of ten different journeys that would have been my favorite back then, even to places I had only visited in books.

But now, in 2016, at the age of 49, I stand with Bill Buckley. My favorite journey is home. I type this aboard a transatlantic flight that is now skirting Baffin Bay, and can hardly wait to see my wife and kids later tonight.

I have just enjoyed one of the most meaningful and spiritually rewarding journeys of my life, among Italian Catholics in Norcia and San Benedetto del Tronto. I will remember this last week always; this inspiration comes at a much-needed time for me. Yet the idea of going back to my everyday life, with Julie and the kids, delights me even more. How did that happen?

Beats me. It’s just gratitude, mostly. I think. It humbles me to think of what a gift I have been given in my family, and in the ordinary. The monks in Norcia were telling me how in the Rule, St. Benedict instructs them to treat their everyday utensils as if they were vessels of the altar. There’s great wisdom in that. My ordinary life back in Starhill, with its ordinary rhythms, is where God is. In San Benedetto del Tronto, those Catholics aren’t living in charming Italian hill towns, but in ordinary housing. But they live with a sense of gratitude to God that consecrates it all. My God, you should be so lucky as to ride around town with that mad genius Marco Sermarini! He will make you feel in your bones that life is a gift to be cherished, celebrated, and defended. You should have heard him talking about the tiny grove of olive trees he and his family cultivate on the side of a steep hill. It’s nothing, really, but it’s everything. To see the world like he and his compadres do — well, it’s to realize that home is our own garden of Eden. You just have to see it in the right way.

How strange and wonderful to go halfway around the world and spend a week among strangers, and to want nothing more than to come home to my little country town, and be with my own ones. Best journey ever!

Trump The ‘Fraud’

Though we’ve never actually met, I consider Michael Brendan Dougherty a friend and fellow traveler. I think he has written a very important column about the Trump phenomenon, one that’s especially so because he’s a paleocon who doesn’t have much use for the Republican Party. Excerpt:

The conservative movement’s resistance to Donald Trump has been almost completely ineffectual. And at times, they let Trump’s incoherence become the basis for making their own criticisms of him incoherent. Consider how normal people might react to hearing Trump accused of being at once a liberal Democrat like Obama and a European fascist. But in the last few days, perhaps too late, that movement and their champion, Marco Rubio, have finally hit upon the truth about Trump: He’s a fraud.

That line of attack has the virtue of truth, and people tempted to throw in with Trump should consider it. Many people in or around the conservative movement — people I know — are so disgusted with the political and intellectual atrophy of the Republican Party and the conservative movement that they are anxious to blow the whole thing up via Donald Trump’s candidacy. They believe Trump’s verbal crudity is a small price to pay to break up the civilized crudities that pass as normal conservative politics, like the desire to launch more wars of choice in the Middle East, or the American economic and immigration policies that enrich elite clients and leave the average Trump supporter worse off. I wouldn’t begin trying to argue that such people should support Marco Rubio or Hillary Clinton. Just don’t actually support Donald Trump; he will make a fool of you.

At this point, I think we have to presume that Trump will get the GOP nomination. How in the hell are the Republicans going to have a convention when the entire party’s institutional apparatus hates his guts?

If he is the nominee, I am by no means confident that Hillary Clinton will beat him. What happens if Trump becomes president, and can’t fulfill his far-reaching promises? What do those who voted for him do? What happens to our politics? It will be fascinating, and more than a little unnerving, to observe how a President Trump, feared and loathed by so many, including in his own party, would govern.

It is impossible to escape the conclusion that we are headed into a period of great instability in American politics, no matter how this primary season and the fall election turn out. If Hillary beats Trump this fall, the mood in the country will be so foul that she will have trouble governing too, I think. And what kind of opposition will the Congressional Republicans, shell-shocked by such a resounding repudiation by a majority of their own voters, be able to muster?

Strange days indeed. Also, please read Andrew Bacevich’s take on Trumpism, published on TAC today. TAC readers will know that Bacevich is no GOP shill, and has been a principled critic of US war policy from a realist point of view. Excerpt:

If Trump secures the Republican nomination, now an increasingly imaginable prospect, the party is likely to implode. Whatever rump organization survives will have forfeited any remaining claim to represent principled conservatism.

None of this will matter to Trump, however. He is no conservative and Trumpism requires no party. Even if some new institutional alternative to conventional liberalism eventually emerges, the two-party system that has long defined the landscape of American politics will be gone for good.

Should Trump or a Trump mini-me ultimately succeed in capturing the presidency, a possibility that can no longer be dismissed out of hand, the effects will be even more profound. In all but name, the United States will cease to be a constitutional republic. Once President Trump inevitably declares that he alone expresses the popular will, Americans will find that they have traded the rule of law for a version of caudillismo. Trump’s Washington could come to resemble Buenos Aires in the days of Juan Perón, with Melania a suitably glamorous stand-in for Evita, and plebiscites suitably glamorous stand-ins for elections.

That a considerable number of Americans appear to welcome this prospect may seem inexplicable. Yet reason enough exists for their disenchantment. American democracy has been decaying for decades. The people know that they are no longer truly sovereign. They know that the apparatus of power, both public and private, does not promote the common good, itself a concept that has become obsolete. They have had their fill of irresponsibility, lack of accountability, incompetence, and the bad times that increasingly seem to go with them.

Trump is Nemesis to the Establishment’s hubris. Democrats who chortle at the (deserved) misfortune of the Republican Party are whistling past the graveyard.

Spotlight On Truth

(I wrote what follows while over the Atlantic aboard a United Airlines flight. I just discovered that this Dreamliner has Internet access. Greetings from somewhere over the Labrador Sea.)

On the flight back to the US, I noticed that United is showing Spotlight, the Best Picture winner, as part of its in-flight viewing. I was very pleased to see this; I’ve wanted to see the movie since I heard about it, but films like that rarely come to my part of the world. I thought I would have to see it on iTunes or Amazon Prime. Soon after the plane took off from Frankfurt, I settled back to watch the movie.

A little more than two hours later, I was in tears. That shocked me, to be honest. It has been 14 years since those days, and I had forgotten a lot of that material, and buried some pretty painful memories of what it felt like to deal with the material when the Boston Globe started breaking its stories about the massive child sex abuse crisis in the Catholic archdiocese, and a cover-up that involved not only Cardinal Bernard Law, but quite a number of people in the establishment of that very Catholic city – including, the movie makes clear, some decision-makers at the Globe who were given reason to believe there was a story there as far back as the 1990s, but who didn’t want to see what was right in front of their faces.

It is hard to find someone more cynical than I am about the media business, but I tell you, watching this movie made me so proud of the Globe reporters and editors on the Spotlight team, but also of my profession. I knew most of the narrative portrayed in the film, but I did not fully grasp until seeing this movie how difficult it must have been to tell this story in Boston. There’s a scene near the middle of the film in which one of the Catholic good ol’ boys (do they have Yankee good ol’ boys) is talking to Walter “Robby” Robinson, the editor in charge of the Spotlight team, trying to dissuade him from doing the investigation. Robinson, a lapsed Catholic, is himself is one of the good ol’ boys, and his old friend appeals to tribal solidarity. The new Globe editor, Marty Baron, whose idea it was to pursue the story, is not from Boston, says the guy, and he’s a Jew. What does he know about us?

I smiled at that. The very first story I ever wrote about the abuse scandal was back in 2000 or 2001, when I was a columnist for the New York Post. I can’t remember how the story even came to me, but it involved the adolescent son of working-class immigrants in the Bronx, and three priests at his local parish. The kid’s father was back in Latin America, and his mother was having trouble with him acting out. Being a Catholic, she sent him to the local church, hoping that the fathers there could talk some sense into the boy. They ended up passing him around among them as a sex toy.

When the kid’s father arrived in the US and found out what was going on, he went straight to the Archdiocese of New York. He met with an official there, who offered him a settlement check in exchange for signing a contract that made the Archdiocese’s lawyers his family’s legal representative in this case – in other words, to bury the thing.

That kid’s father might have been a working man from Latin America who didn’t speak a word of English, but he understood what was happening. He went out and hired a Jewish lawyer, and sued the church on behalf of his son. Smart man. Often, it takes an outsider.

The most affecting scenes in the film are the ones involving adult victims telling their stories to reporters. It probably startled many viewers to see how emotionally shaky these victims are. But it’s often true. I think of an abuse survivor I used to know in New York, a man who was by then in his late 50s or early 60s, and who was a mess. He was a recovering alcoholic, and had been extremely promiscuous with other men – many of them priests – until he got sober. He had been raped as a kid by a priest. When as a boy he told his Irish Catholic working class mother that he had been sodomized by this priest, she slapped him hard and told him never to speak that way about God’s priests. The forced sodomy at the hands of this molester priest continued unabated. The kid was all alone in the world. The priest, who is no longer alive, rose high in the Catholic hierarchy, and his name is remembered today with honor.

Watching Spotlight, I thought about that Catholic kid who was a ruin of a man, and I wondered whatever became of him. I found him difficult to be around sometimes, because he was so jittery, just like the character based on Phil Saviano in Spotlight. That New York man became a good source for me; having been sexually involved for much of his life with priests, he had deep knowledge of where the Archdiocese buried its clerical bodies, so to speak. Had I met him before I started covering the abuse story, and learned how extremely damaging child rape (especially at the hands of a priest) can be, I would have been exactly like the Globe editors in the movie who dismissed Saviano years earlier, assuming that he was a nut.

I winced at a scene later in the film when one of the Catholic good ol’ boys tells Robby that the Globe shouldn’t run the story because people need the Church “now more than ever” (this is shortly after 9/11), and besides, Cardinal Law “is not perfect,” but he’s a good man, and we can’t let a few bad apples, blah blah blah. I had Catholic establishment people – more than one – telling me, an observant and quite conservative Catholic at the time – the same thing. Except the phrase that they tended to use was, “I know the bishops haven’t exactly covered themselves with glory, but …”. It’s stunning to think of it now, in 2016, after all we know, but there were quite a few good Catholics back then who rationalized ignoring the horror in just that way.

For me, the most emotionally wrenching scene comes when Globe reporter Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) reads the formerly sealed records in which Margaret Gallant, a woman in whose family seven – seven! – boys were molested by Father John Geoghan, wrote to Cardinal Law Cardinal Law’s predecessor, Cardinal Medeiros, begging him to help. [NFR: A reader rightly corrects me; other documents show that Law was very well aware of Geoghan’s history, including this letter to his predecessor. — RD] (Rezendes reads more than just that document, but the film makes it stand for them all, because it was the most shocking of the lot.) How well I remember reading the Margaret Gallant letter when the Globe published it. I was sitting at my desk at National Review, and I felt like I was physically coming apart. How any human being, much less a cardinal archbishop, can read something like that and not move heaven and earth to do justice – this I could not understand. Bernard Law is a morally depraved man. Pope John Paul II is now a saint of the Catholic Church, and though I am no longer Catholic (therefore not required to recognize his canonization), I believe he really is a saint. Nevertheless, it was Pope John Paul II who reassigned Bernard Law to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, one of the most honored churches in the Roman Catholic world. The depraved indifference to the suffering of victims pervaded the Catholic institution.

I had only one child at the time, and he was only three years old. I would read stories, or court documents that had been released (Judge Constance Sweeney in Boston, an Irish Catholic jurist who put them all into the public record, is one of the heroes of this story), and I could not help thinking, if this had been my son, the bishops would have gone out of their way to crush me and my family, just like they did to so many Catholic families. The thought tormented me. After I started writing about it for NR, people would call me out of the blue and start telling their stories. Victims, or family members of victims. Many of these accounts I had no way of confirming. Most of them were somewhat confirmable, but absent the source producing documents or being willing to go on the record, my hands were tied. Some of my sources were priests who would inevitably say these stories need to get reported, that the stables needed cleaning, and asking me, a faithful Catholic, to be the one to tell it.

In nearly every single case, I was powerless to do anything, because I could not convince these sources to talk. In one case, the source was a woman who worked for her local diocese. Her husband had left her, and she was raising kids alone. She needed her job, and wouldn’t go on the record. Even though I had independently confirmed some of the details she gave me, I couldn’t write it without her. There was too much at risk to her livelihood, she said. This woman was out in the Midwest, and I worked for a little opinion magazine that had no travel budget for things like this. The sense of powerlessness I felt in those days, having to carry that knowledge, and being unable to do anything about it, nearly drove me crazy.

I’m actually kind of serious. I was consumed by anger at the Church. Every now and then I’ll run across something online that I wrote on NR’s blog back then, and I’ll be embarrassed by how strident my prose was. I was a Catholic who was in a lot of pain, and though I didn’t know it at the time, I was having my faith pulled out of me like a torturer armed with pliers wrenching the nails out of the fingers of his prisoner.

Finally, in the summer of 2002, my wife prevailed on me to see a Catholic therapist over my anger. That’s how I ended up in the hands of Phil Mango, a quack who, when I published something criticizing John Paul’s inaction on the scandal, screamed – literally, screamed – at me in a therapy session that I was a “new Luther,” and telling me that my wife was going to leave me if I continued criticizing the Church in public. I should have slapped the guy, but I was shell-shocked, and took it. I even paid him his fee. Later, when I got home and told my wife what had happened, she called Mango and read him the riot act. I wrote demanding my money back for that session, and ending our relationship. He sent the money back. I should have reported him to the state authorities for malpractice. Those were crazy times. He was tight with the Legionaries of Christ and their Regnum Christi group. It came out later that the revered head of the Legion, the Rev. Marcial Maciel, was a serial molester who had a secret mistress and children.

Sorry, I digress. Anyway, the most emotionally wrenching scene for me was the one where Rezendes is breaking down on the back porch of a newspaper colleague’s apartment. He’s finally seen the depths of the church’s depravity in Boston, and, as he puts it, “something cracked.” He says he was raised Catholic, and had drifted from the Church, but always thought he would return. Now, knowing what he knows, that path is closed, and it’s tearing him alive.

Something cracked. For me, that something cracked in 2005, after a filthy liar of a priest of considerable charm got close to my family before a friend and I accidentally uncovered the truth about him. I wrote a story in the Dallas Morning News about it, because my family was attending that parish at the time. I got an angry letter from a guy in the parish with whom I was friendly, telling me that he’s on the parish council, and all those on the council knew the truth about Father Clay, but decided not to disclose it to the rest of the parish. This guy was defending their secrecy. It was for the good of the church. They accepted into their parish a priest who was accused of molestation and suspended by his bishop up in the Northeast, and chose not to tell their fellow parishioners – or, as it happens, the Bishop of Fort Worth (it was a complicated story). Yet I was the evil one for outing him. The betrayer of the tribe.

That was it. There was no more tribe for me to betray. I lost my Catholic faith. Gone. Something cracked.

I formally left Catholicism for Orthodoxy a decade ago, and before long fell right back into the same kind of mess, fighting battles within the Church among bishops and insiders, a war I was no longer equipped emotionally or spiritually to wage. I don’t do that anymore, not because there aren’t important issues at stake, but because I can’t handle it, to be honest. I tell people that once you’ve stared into that Palantir, it does something to you, and you’re not the same anymore. I cheer for those within Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Protestantism, or any faith who are willing and able to take on the institutional powers that seek to destroy the weak to protect themselves, but I’m useless on that front today.

How strange it was to see Spotlight on the way home from one of the most spiritually moving and meaningful journeys of my life – one spent surrounded by faithful Catholics, in very Catholic settings (a monastery, in Italy). I think one reason I love the Norcia monks so much is that they embody what is best about the Catholic Church. Since visiting Norcia for the first time in 2014, I’ve told Catholic friends who are angry and afraid over what’s going on in their Church to go to Norcia and be calmed, and even healed. Now, I would add, “Go to San Benedetto del Tronto and talk to the Tipiloschi.” I would give this advice to any Christian, no matter what their church or tradition, who is tempted to despair over the brokenness in the Body of Christ. Don’t misunderstand: I am firmly committed to Orthodoxy, though it pains me somewhat to feel separated at the ecclesial level from the Norcia monks and the Tipiloschi. But I can live with that, because God sees our hearts, and my faith tells me we are somehow in the same mystical communion, though not visible. One healing thing I have learned from practicing Orthodoxy – something that I wish I had known in my bones as a Catholic – is that it is possible to live a deeply Christian life of prayer, communion, confession, fasting, Scripture reading, and all the rest, without dwelling on what the ecclesial institution does or does not do. In fact, for some of us, it might be the only way to live a deeply Christian life.

In fact, I think it might be providential that I saw Spotlight at the conclusion of this pilgrimage. It doesn’t weaken my faith, or cause me to doubt anything I saw or heard over the past week. Truth is, reliving all that – “all that” – in a two-hour film made me understand how important it is to live our religious lives with integrity and responsibility. That means praying, reading Scripture, and deeply grounding oneself in the faith. If you think being a Christian is simply about knowing things – as in, getting the doctrinal questions correct — you are setting yourself up for a very great fall. Trust me on this one: it’s what happened to me. You can only run from factual truths like what the Spotlight team uncovered for so long, and if you haven’t formed your heart all along according to spiritual, even metaphysical, truths, your faith may not stand.

Spotlight reminds me how much I took for granted as a Catholic back then, before the time of testing. I trusted the institution – I didn’t just trust it, I idolized it – and I trusted my own judgment. I thought I knew where the lines of good and evil ran within the Church, and between the Church and the World. And I thought the main thing about being a Catholic Christian was assenting to the teachings, receiving the sacraments, and following the rules. Those things are all important, but the main thing is conversion of the heart. The heart is deceitful above all things, as the saying goes, and the unconverted heart is a mirrored labyrinth in which it is fatally easy to lose oneself. Spotlight shows one of its strengths at the very end, when Robby, played by Michael Keaton, discovers the truth about himself: that at one time he too chose to look away from the truth, preferring the safety and comfort of illusion.

The scene that made me break down was the very last one, on the day that the Globe broke the first of over 600 stories, setting off a chain reaction of global import. The phones at the paper rang off the hook, with ordinary people calling the reporters to say it happened to me too. It took the tireless courage of victims’ advocates like Phil Saviano, the bravery of victims willing to go public, priests like Fr. Tom Doyle, lay Catholics who spoke out, and journalists willing to buck a powerful establishment to tell the truth, for the truth to set those poor souls free – and in fact, for the truth to set all Catholics, and even all Christians, free from the lie that evil like this doesn’t happen with us.

It is better to be a martyr to the truth than to live by lies. The life you save may be your own – or your child’s. And so might the Church you save.

All of us Christians in the West have entered into a difficult time, a darkening time, a time of trial. Nothing could be more important now than to ground ourselves in the unsentimental truth about the human condition. We can’t afford the false pieties that led so many people to support a corrupt system that traduced the Gospel and caused so much agony. All of us are capable of deceiving ourselves to protect our idols. I have never talked about the abuse scandal with Father Cassian, prior of the Norcia monastery, nor would I ever put him on the spot about that topic. But the words he said to me at the conclusion of our first meeting in 2014 come to mind now, as I’m finishing this reflection. We had been talking generally about the signs of the times, and the trials that all of us Christians are going to undergo. Though he is profoundly a man of the Church, Father Cassian is also a man who does not give one the impression of having a mind occluded by illusion. He is a man of gravity and depth, and one gathers that his is a hard-won serenity. With that in mind back in 2014, I asked him where he found his hope.

“In the Lord,” he said, firmly. “And only in the Lord. Nothing else lasts. He is the only one who will not disappoint.”

Wisdom! Let us attend!

The Old Donkey in the Empire’s Ruins

I’m sitting in the Rome airport, about to start the long journey back home. When I land in Baton Rouge 18 hours from now, we will know how the Super Tuesday vote went. I expect it to be a big night for Donald Trump. I also expect nothing good on the political front from now on. It would be nice to be surprised, but I don’t think I will be surprised.

I was thinking last night, on the long bus ride to the airport, about Niccola, the homeless man from Bari who stayed in my guest apartment at the monastery in Norcia. He spoke almost no English, but managed to convey to me his deep frustration that the Italian government is helping Middle Eastern refugees find housing, but doing nothing for him. German Chancellor Angela Merkel yesterday doubled down on her open borders policy, which is flooding Europe with migrants. That poor man, Niccola, is powerless to stop it, even in his own country. If there were a Trump here, and he could vote, I bet Niccola would vote for Trump. I saw the new Rand study showing the factor most determinative of a Trump voter is the degree to which he or she feels powerless. Trump appeals to globalism’s losers. There are a lot of losers in globalism.

Enough about Trump. I have something inspirational to talk about. See that man above? That’s Marco Sermarini, with his great friend G.K. Chesterton. If you ask me, he’s a lot more important to the future of American Christianity than any politician for whom you will vote today. I spent the last couple of days with him and his tribe in San Benedetto del Tronto, a small city on Italy’s Adriatic coast. I wanted to go meet them all on this trip because in 2014, when I first met Father Cassian Folsom, the prior of the Benedictine monks of Norcia, he told me that any Christians who want to make it through what’s coming with their faith intact had better do what the San Benedetto del Tronto folks are doing.

Now, I understand exactly what Father Cassian meant. He’s right. These Italians have it all figured out.

I’m going to save most of this for my book, but I wanted to tell you a little bit about it now, because I think a lot of us could use some hope.

Marco is a leader of a group of faithful orthodox Catholics, about 30 families, who live in and around the city. They have been together as a group since the early 1990s, when they formed a fraternity called the Tipiloschi, following the example of Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati, an Italian Catholic social activist of the early 20th century. The men came together for prayer and for doing good works in their city. Eventually they married, and the Tipiloschi became a big family affair.

They are not affiliated with any particular parish, though they have developed a very close relationship with the monastery in Norcia, a 90-minute drive over the mountains. In 2008, they started an independent school, the Scuola Libera G.K. Chesterton (“libera” means free, and in this case it means the school takes no money from the government). The school’s motto is a quote from Chesterton: “A dead thing goes with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.”

That’s how they roll. They are fiercely, joyously countercultural Catholic traditionalists. I visited the school, had pizza with parents, and the thing you notice most of all is how happy these people are, and how … normal. They are open about how serving Jesus Christ is the guiding principle of everything they do. And they do a lot. There’s the school, which they open to people outside their community, and keep tuition low so working people can afford it. As distributists, they run several cooperatives, including one called Hobbit (they’re big Tolkien fans), that organizes gardening, plumbing, and other kinds of manual labor; part of its function is to give jobs to prisoners trying to transition back into society. They run a sports club, and pooled their resources to buy an abandoned piece of property on top of a hill overlooking the Adriatic. The group and their families have been working to restore it as a retreat. They meet there for sports, for picnics, for mass, for catechism lessons, and for gardening. They have a small farm there to teach their kids (and any other kids who want to come around) how to raise fruits and vegetables.

Here is the garden. This was once a massive briar patch. They cleared it and cultivated it. Now it’s a living thing:

They’re still working on the property. I met someone from the Hobbit cooperative who unfolded plans for the orchard trail:

Notice this detail of a tiny hut they’re building:

The Tipoloschi teach in their school, giving of their own expertise in different subjects. Marco’s wife Federica is the principal. She’s a former public school teacher who believed there had to be a better way for kids to learn. The Tipiloschi families help each other out with homeschooling too (the Chesterton school is a half-day affair, followed by homeschooling in the afternoons. Yesterday I saw Federica and Marco’s teenage son Pier Giorgio doing Latin homework at the kitchen table with a couple of school friends. Then they packed up and were headed to a nearby home for severely disabled children to do a gymnastics program with them.

The Tipiloschi revere the Norcia monks, and seek to live out a Benedictine spirituality in their own lives. Marco, a lawyer and head of the Italian Chesterton Society, is a force of nature. Really and truly. He is ferociously localist, and understands that the beautiful, rewarding Christian life they have built in San Benedetto is only possible in community, and because everyone gave up the idea of going off to the big city to chase after worldly success. Some things are more important, they decided. The great goods they have with their families in the Tipiloschi are only possible because of the stability to which they’ve committed themselves.

“Going away from here to chase ‘success’ is for people who want to be slaves,” Marco says. “Here, we are free.”

Here is stability for you: Marco in his tiny olive grove running down the side of a hill west of town:

He cultivates these trees with his children, and makes the family’s olive oil from them. He worked these trees as a boy with his father, Gino, who worked them with his father. Gino, now 90, hid in the base of this olive tree as a five-year-old boy. Marco’s kids hide there now:

Again, all of the efforts of the Tipiloschi are open to anyone who cares to participate. At the hilltop property (Santa Lucia they call it, after a nearby church), I saw Marco embrace a tough-looking teenager, and tease him affectionately. Clearly they have a father-son relationship. I asked Marco about him, and he said the boy was in real trouble with drugs (or perhaps the law in some other way), but the Tipiloschi brought him into their circle, prayed with him, taught him to work, to cultivate, and restored him (actually, Marco would say that God restored him through their active love for the boy). There are more than a few kids like that in their circles.

Americans hearing about the Ben Op have this idea that it’s all about running away from the world, hunkering down, and being miserable. If that’s what you think, go to San Benedetto del Tronto. Those people love their lives, they love their lives in community, they love Jesus Christ, they love being truly, deeply Catholic, and they’re just so grateful for everything.

I could tell you far, far more about these people, and will do in my Benedict Option book. Their spirituality is profound. They can read the signs of the times. They worry about the break-up of the family, and the widespread loss of faith. But they are not running for the hills. They are cultivating the hills (ultimately they hope to move the Chesterton school to the Santa Lucia property), and the bonds of their own community. They go to the monastery for spiritual direction, and to help out, and the monks sometimes come to them. They meet all the time for meals, prayer, and study of the faith and the lives of the saints (“We have to have heroes,” says Marco. “We have to teach our children and ourselves that the life in Christ is something real, something incarnate.”) They go on holiday together.

“We take over hotels,” says Federica, laughing. “There are around 130 of us. The oldest is 89, the youngest is a few months old.”

Driving through the hills yesterday, I asked Marco if he ever despaired of this world.

“Oh sure,” he said. “Some nights I lie awake at night worrying about the way the world is going. I pray to God and ask Him for help.”

I tell you this so you know that Marco is not oblivious at all to the travails of the post-Christian world. But, he told me, we must follow the example of St. Benedict, and figure out ways to serve Christ in the ruins of our civilization, and go forward with hope. The times call for Christians to be radical, said Marco, and that is something we have to accept. This is one of those times in history, he said, where we have to “save the seed” for the future, and we must be aware of the signs of the times. As we determine how to respond to the challenges of being Christian in this post-Christian civilization, we don’t need courage, he said, as much as we need imagination.

“Don’t worry if you haven’t got it all figured out now,” he said. “Don’t worry if you aren’t a thoroughbred horse. If there aren’t any thoroughbreds, well, use a donkey. I’m an old donkey doing the best he can with what he has. But remember, Jesus Christ came into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey.”

Just so. I cannot wait to tell you all more about the Norcia monks, and about the Tipiloschi and the beautiful community they have built. There is hope. I have seen it over this past week, and have lived part of it. It’s the Benedict Option, and it’s really real.

I’m about to get on the plane. Will check in later. If you want to hear more stories about what I saw this past week in Norcia and in San Benedetto del Tronto, come out to Hill House, the Christian study center at the University of Texas in Austin, on Friday. And that night, come hear me talk about Dante at UT:

February 29, 2016

Lands’ End Does Right Thing

A reader forwards me this e-mail that came to her after she wrote to Lands End over the Gloria Steinem flap:

Dear [Name]

Thank you for your email and sharing your honest feedback with us.

We apologize for any offense and concern caused with our recent featured interview with Gloria Steinem. It was never our intention to raise a divisive political or religious issue.

We greatly respect and appreciate the passion people have for our brand. Lands’ End is committed to providing our loyal customers and their families with stylish, affordable, well-made clothing.

We sincerely apologize for any offense.

Sincerely,

Kelly Ritchie

SVP, Employee & Customer Services

Lands’ End

As far as I’m concerned, that should be the end of it. The company screwed up, it apologized, and we customers should forgive. I suspect Lands’ End has learned its lesson. Good on the customers for complaining, and good on Lands’ End for responding as it did.

Interesting to consider, though, how this would have played out if the company had featured not a pro-abortion feminist, but an LGBT activist, and received complaints because of it.

February 28, 2016

The Terror of Trump Tuesday

So the GOP candidate likely to sweep most Super Tuesday states today on TV repeatedly declined to disavow the endorsement of former top Klucker David Duke. Good luck, Republicans, with that guy in the general election.

I was talking with a Catholic friend today about the near-collapse of the Catholic Church after Vatican II. He said, reasonably enough, that it the Church and Catholic society had been healthy, it would not have fallen apart, and certainly not so quickly. I think something similar is the case for the GOP. For me, the aha moment was when Trump trashed the Iraq War on the South Carolina debate stage. Yeah, he was unfair in some of the accusations he made, but the most astonishing thing about it was that 13 years have gone by, and still, it’s taboo for GOP presidential candidates to criticize that disastrous war.

That is not a party with a brain. Read David Frum’s Storified tweetstorm about how the GOP brought Trump onto themselves.

I had planned to blog something today catching up to some Trumpsplaining posts I’d read over the weekend. Trump’s big mouth makes it all too easy to not take the Trump phenomenon seriously. It really is unthinkable that a major presidential candidate would waffle on the KKK — the KKK! — but I think it would be a mistake to think that that’s all we need to consider about him. The sort of radicalism that Trump symbolizes doesn’t just emerge overnight. I thought Peggy Noonan’s column about this stuff was insightful. Excerpt:

If you are an unprotected American—one with limited resources and negligible access to power—you have absorbed some lessons from the past 20 years’ experience of illegal immigration. You know the Democrats won’t protect you and the Republicans won’t help you. Both parties refused to control the border. The Republicans were afraid of being called illiberal, racist, of losing a demographic for a generation. The Democrats wanted to keep the issue alive to use it as a wedge against the Republicans and to establish themselves as owners of the Hispanic vote.

Many Americans suffered from illegal immigration—its impact on labor markets, financial costs, crime, the sense that the rule of law was collapsing. But the protected did fine—more workers at lower wages. No effect of illegal immigration was likely to hurt them personally.

It was good for the protected. But the unprotected watched and saw. They realized the protected were not looking out for them, and they inferred that they were not looking out for the country, either.

The unprotected came to think they owed the establishment—another word for the protected—nothing, no particular loyalty, no old allegiance.

Mr. Trump came from that.

I offer to you this excerpt from a reader’s e-mail as more explanation. The reader says he will not vote Trump, but he gets where Trump’s coming from. I slightly edited this to protect his privacy:

Do you read Jim Geraghty’s [National Review writer] morning newsletter? It’s often valuable but some of his commentary lately has gotten very problematic. In writing about these voters, he says today:

“you only have a high school education, your economic prospects are going to be limited, no matter who is president. We can argue about whether employers overvalue college degrees, but it’s hardly been a secret that employers in the highest-paying fields aren’t interested in job applicants with only a high-school degree, or high-school dropouts.

Today, lot of Americans are telling anyone who will listen, “I got screwed.” You risk an apoplectic frenzy if you dare respond . . . “Are you sure? Are you absolutely certain that your disappointing life circumstances aren’t a result of the decisions you’ve made? At all?” If a man looks at his life, and concludes his prospects for a better future are slim, how much of that is society or the economy’s fault, and how much of it is his fault? It’s a lot easier to blame Wall Street or the richest 1 percent or the elites than to acknowledge our own mistakes and bad decisions.

Maybe I’m a cynic, but I keep running across “victims” who don’t seem like actual victims. Was the housing bubble really just an endless series of Wall Street fat-cats and “predatory lenders” going after well-meaning, hard-working Americans who just dreamed of owning a home? It had nothing to do with people buying houses they couldn’t afford and assuming they could sell them quickly?

Back on January 26 of last year, the Washington Post wrote a lengthy profile piece presumably meant to be a heartbreaking portrait of victims of the housing bubble in Prince George’s County. The article showcased Comfort and Kofi Boateng, legal immigrants from Ghana, who “struggle under nearly $1 million in debt that they will never be able to repay . . .”

Wait for it…

“on the 3,292-square-foot, six-bedroom, red-brick Colonial they bought for $617,055 in 2005. The Boatengs have not made a mortgage payment in 2,322 days — more than six years — according to their most recent mortgage statement.”

These folks have lived in a six-bedroom house and haven’t paid a dime for six years, and we’re supposed to believe they’re the victims here?

The Postcontinued, “Their plight illustrates how some of the people swallowed up by the easy credit era of the previous decade have yet to reemerge years later.” Wait, living in a house for six years for free is a plight?

You probably remember this poster boy for Occupy Wall Street: “Frustrated by huge class sizes, sparse resources and a disorganized bureaucracy, [Joe Therrien] set off to the University of Connecticut to get an MFA in his passion–puppetry. Three years and $35,000 in student loans later, he emerged with degree in hand . . .” (Don’t worry; these days Therrian is using his puppetry skills in a show, The Seditious Conspiracy Theater Presents: A Monument to the Political Prisoner Oscar Lopez Rivera.)

Look, before you take on five or six figures in debt, maybe you should take a little time to think about how much money you’ll be able to earn when you’re finished. That’s not “the system” being unfair to you; that’s supply and demand.

Promoting personal responsibility is hard enough without political leaders who keep rushing to the cameras to tell Americans that nothing is ever their fault; it’s always the work of these nefarious sinister, powerful forces.

Is there any sign that Americans have learned the right lessons from the Obama years? Doesn’t it seem like we’re hungrier than ever for new scapegoats?”

The reader adds:

To which I say, come the f**k on.

Now on the one hand a lot of Trump voters aren’t going to read or care what Jim Geraghty has to say but this is getting to be a bit much. Of course there are Occupy Wall Street/SJW types out there who want the government to subsidize their puppet plays, and of course there are plenty of people who leveraged gobs of debt in their personal lives who have yet to recover from an economic crash in 2008. But from my own experience there are a lot of people like me. Indulge me for a minute:

Graduated high school in 1999 and went to school at [state university]. Finished in four years with a double major in history and political science. No idea what to do with a job (and no good advising in undergrad) so I worked at a law firm while decided between law school and grad school. Went to grad school and got M.A. in History while prepping for a PhD elsewhere. Got married while working on the M.A. PhD programs turned out to be a bust (the quality programs had acceptance rates of something like 5%) so I opted to go into teaching high school. Right now I’m working in insurance because I wanted to make a career change three years ago. It’s not worked out for me and my family so I’m probably going back into education and I’ll try to do some volunteer work that perhaps I can turn into a full-time job in the years to come. But here’s the rub – there was a time, not that long ago, when a guy could graduate from a major public university in his region with a B.A. in humanities and could get a job doing just about anything. It was understood that if you could read and write in a cogent fashion you could probably learn to be a decent banker or advertising man, and of course education and law were always options. But now if you don’t have a marketing degree, good luck getting a job in advertising or marketing unless you want to be the kid getting coffee.

When Geraghty says “we can argue over whether employers overvalue college degrees,” he’s wrong – there is no argument. Employers do overvalue college degrees. It’s not just some goober at Wellesley that majors in Indonesian LGBT puppetry – if you’ve got a humanities or social sciences degree (Economics excluded), you better have a law degree (worth less and less all the time) or hope you’ve got a good personal network that can help you land a job with someone willing to overlook the fact that your degree isn’t specific to a career field.

Geraghty – and presumably other conservatives – can call this excuse-making all they want, but when your entire educational experience in high school and undergraduate points in one direction and then the job market changes underneath your feet – whose fault is that? I could be in better financial shape if I had used a credit card less often or whatever, but my career prospects and earning potential wouldn’t be any different. I don’t think I’m alone – I’d guess a lot of Bernie voters have similar backgrounds to mine. The system – their education and their employers (real and potential) did in fact let them down.

Now I won’t vote for Trump – I’m supporting Rubio in the primary and would shift to Cruz if I had to but I find myself agreeing with Michael Brendan Dougherty on this (Douthat and Frum have done well, too). For what it’s worth, Kevin Williamson isn’t entirely wrong, either, but I think MBD is more right than Kevin. (I taught at an all-white school that was a weird mix of rural and suburban so I know about working class moochers, as I’d wager you’ve also seen in rural Louisiana).

But this is a classic example of how some conservative opinion makers are completely out of touch with reality. It’s similar to another conservative tendency, one that has feed Trumpism – when for years all liberals were derided as latte-swilling, Volvo drivers. I knew at twenty-one that was b.s. but all it did was polarize talk radio listeners. More damning has been the tendency to call anyone GOP legislator who didn’t do the immediate bidding of the talk radio crowd a squish who was more concerned about getting an invite to someone’s Georgetown cocktail party or chomping foie gras at Bistro du’Coin in DuPont Circle – now the anti-elitist crowd has come round to support Trump. So when Rush (who I used to love) says he’s not responsible for this, he does in fact bear some measure of responsibility for this nonsense.

Lastly – on Trump’s Iraq comments. I think he – and you, alas – are wrong for two reasons. One, Trump is blaming W for the WTC falling. That’s a completely unreasonable criticism. [NFR: I agree. — RD] Second, it is perfectly reasonable to say as Rand Paul said, that invading Iraq was a serious error. I can live with that; but Trump is accusing GWB and his advisers of intentionally misleading the American people from the get-go, and yes, that’s moving into some conspiracy territory more in line with Code Pink or ANSWR. That’s too far, even if one wants to make the case that Iraq was a mistake (an argument I would rent, but not buy).

Unless there’s a major turnaround for Rubio or Cruz on Tuesday, that’s going to be the day that the Republican Party as we have known it dies. As I’ve said before, it will have been a suicide. Again, David Frum explains it in a few short tweets. Me, I cannot think of a more symbolic moment in this regard than the Republican presidential candidates, except for Trump, being unable to say the Iraq War was a mistake.

Norcia Diary.3

I apologize for being incommunicado these past few days. The wifi situation was dodgy the whole time in Norcia, and my last three days there, it was impossible. It’s just as well, I guess. I came down with a ferocious cold, and spent a disappointing (to me) amount of time between interviews sleeping and, when the Sudafed wasn’t really working, considering the upside of decapitation. Unfortunately my head was full of what pigs slop in, so I didn’t get to go to peeg farm.

I was taken extremely good care of by Brother Ignatius, the guestmaster at the monastery. He’s from Indonesia — Java, to be exact. He brought me cookies on my last night in town. What a great guy:

The other day I interviewed Brother Francis, from Dallas, in the monastery brewery. Brother Francis is the brewmeister. I tried to get this image out of my phone, without luck, until today. We talked about our mutual friend, Father Paul Weinberger. And I drank a goodly portion of his dark beer, which is astonishingly delicious. There’s nothing quite like drinking beer at table with the monks who brewed it. Here’s the King of Birra Nursia:

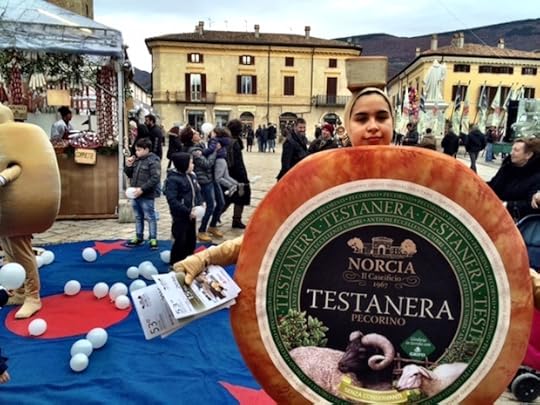

This past weekend, the town held its winter gastronomic festival. Here’s what you buy in Norcia: cheese, cured meats, and truffles. Vendors came from around Italy to sell cheese, cured meats, and truffles from booths sprawled all over town. I got it together enough to go out and buy cheese to take home to Mrs. Dreher, who loves it more than just about anything else. I bought a ton of the stuff, seems like — various pecorinos (sheep’s milk cheese), and a couple of goat cheeses, as well as a wedge of parmigiano. Here was my favorite cheesemonger. He said he was once a philosopher, but decided he would be better off moving with his wife and kids to the mountains, and making cheese. Wise man!:

There was, of course, meat everywhere, but I bought none because it’s against the law to bring it back to the US. Still, check out this meat log; damn thing was nearly two feet in diameter:

On the piazza, Big Cheese was dancing around:

I completed the last of my monastic interviews this morning, and really felt like I was robbing a bank or something. It is so inspiring to talk with men who have given their entire lives to prayer, and to learn from them. As I’ve said, I’m even more excited about this Benedict Option book than I was when I came. Talking to these monks is like staring into a well that is deep but so clear you can see to the bottom. I have an ever more certain idea of how the book is going to go than when I arrived, and for that, glory to God.

I said my daily prayer rule while the monks celebrated the old Catholic mass in the basilica, all of it in Gregorian chant, and utterly sublime. After lunch in the refectory, I left with Marco Sermarini and his friend Daniele. Marco is a founder of the Scuola libera G.K. Chesterton, a classical Catholic school in the seaside Adriatic city of San Benedetto del Tronto. Marco is hosting me tonight, and I’m interviewing him, his wife, and several of their friends for the book. As Daniele drove the winding narrow road out of the mountains and down to the sea, Marco told me the story of his group of Catholic friends, who came together in 1993 around their love of the faith and the Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati. I don’t want to give the story away here — the Chesterton School is only one of the things they’ve done — but I can say that these folks are the living embodiment of the Benedict Option. They have built strong bonds with the Norcia monks. Indeed, you may recall that Father Cassian, the prior of the Norcia monastery, once told me that Christian families and communities that don’t come together as these people have are not going to make it through the times to come. I thought I would come to San Benedetto del Tronto to see what Father Cassian was talking about.

It’s funny how you know your tribe as soon as you meet them. Early in our car ride across the Apennines, Marco said that the motto of the Chesterton school is this great line of Chesterton’s: “A dead thing goes with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.”

And I thought: oh yeah, my people. Here they are. Marco Sermarini is not sitting around waiting for the world to end. He and his crew are doing what Flannery O’Connor advised: “Push back against the age as hard as it pushes against you.” And, being Italian, they are so much fun!

We’re all going to dinner shortly, and plan to talk about Pope Benedict XVI and creative minorities. I wanted to get this blog post up before that, though, so you all didn’t think that I had been eaten by peegs.

February 26, 2016

Norcia Diary: The Early Church

I am deliberately not writing too many details about my experiences with the Benedictine monks in Norcia, because I want to save this material for the Benedict Option book, which will be out next spring (I’ll be able to announce the publisher once their publicity team gives me the go-ahead.) I do want to say, though, that even though I knew this would be a good trip, I did not imagine how deep and rich this material would be (from the interviews, I mean), nor how much of it there would be. Walking back from my most recent interview, with Brother Evagrius, a 30-year-old from Indiana, the thought occurred to me that this entire experience has been like talking to men from the early Church, except that they talk like we do. If I had heard the same words coming from the mouth of a wizened Greek, Italian, or Russian elder, it would have been no less true, but somehow it wouldn’t have been quite as accessible.

In talking to these men — most of whom are fairly young — this ancient Christian tradition comes vividly alive, and graspable. Father Cassian, the prior of the monastery, steeps the novices in patristics — that is, the writings of the Early Church Fathers — when they come, and the Fathers are almost living presences here in the community. Every single one of those men that I’ve interviewed so far come across as serene but not otherworldly. They have such a profound peace about them, but they are also just … guys. It all flows so naturally, though they would tell you that this is the fruit of dying to oneself every single day, of emptying themselves out so they can be filled with the Holy Spirit. Point is, any idea of a monk as a sort of ghostly, withdrawn figure is immediately dispelled by their humble presence. Their faces glow. You can’t fake that. And when you start talking to them, you begin to understand how profound their commitment to Christ is, and how saturated in the Bible they are, and in the ascetic life. I’ve been talking to each one for an hour, for the book interview, except for Father Cassian, who gave me two hours of his time. I leave these sessions hungry for more.

A reader tweeted to ask me if this experience makes me more or less confident that Reformed Christians will buy into the Ben Op project. I would say more, definitely. It has been very good for me to have a copy of Reformed theologian James K.A. Smith’s forthcoming book on the spiritual power of habit with me. It’s a terrific book — clear, punchy, practical — about how habits train our hearts. I would even say that it’s a must-have text for the Benedict Option. The book has informed some of my questions for the monks, who talk about how all Christians should order their lives habitually to serve God — and about how we can’t just drift through life, or we will miss the mark. That, I think, is where many Evangelical leaders will connect with the book.

Orthodox readers may be surprised to discover how, well, Orthodox this monastery is. There are icons everywhere, and though they are thoroughly and unapologetically Catholic, they focus on how the first millennium of Christianity is our common heritage. The Fathers, as I said, are essential to life in this monastic community. This morning, in my final interview with Father Cassian, he was talking about having hope. He brought up the example of Elder Joseph the Hesychast, the Athonite elder whose fidelity revivified the Holy Mountain after a long period of decline. I was amazed that a Benedictine prior, in the mountains of Umbria, held the example of a modern Athonite elder so dear.

“We have lots of friends on the Holy Mountain,” he said. That is great to see.

I wrote to a Catholic friend just now, telling him that he had to get over here to Norcia as soon as he could. He’s been struggling with some heavy things for a while, and could use some peace and healing. This is a place of healing. I told him that when you are around these monks, you feel as if you have, for a moment in time, been able to glimpse the sun from Plato’s cave. It’s not that they’re perfect (and it would probably embarrass them to death to hear me say that), but that they exemplify — exemplify — what it means to live a life fully committed to Christ, to treat others as if they too were Christ, and to regard God as everywhere present and filling all things.

It’s real, people. It’s really real. These guys aren’t messing around. Br. Evagrius said that it’s essential for Christians today to prepare for martyrdom — not, he emphasized, that he is prophesying anything like that in fact, but rather so that we will live so detached from the world, like the early Church did, that we would be prepared to give our lives joyfully for Christ. As he said these words, his face was beaming, in the same way most young men his age would talk about their favorite college football team going to the national championship.

He said, “When you truly order your life to Christ, it orders everything else in your life. It has to.”

He said a lot more. They all have, and I look forward to telling you all about it in the pages of the book. The spiritual power in this simple place in the mountains, where the monks live simple lives of prayer, work, ascetism, and charity, is a thing of awe. Whether you’re Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox, the kind of thing these monks are doing here — bringing these practices into our lives — is where the renewal is going to come from, sooner or later, in God’s time. Those monks were made for a time such as this.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers