Rod Dreher's Blog, page 557

July 20, 2016

Erdogan’s Coup Against Liberty

While we’re all knotted up over Trump family oratory, Recep Tayyip Erdogan is busily purging the Turkish state and civil society of all suspected opposition:

Meanwhile, the Turkish government crackdown widened on Tuesday to include the education sector and government departments.

Turkish media announced that:

15,200 teachers and other education staff had been sacked

1,577 university deans were ordered to resign

8,777 interior ministry workers were dismissed

1,500 staff in the finance ministry had been fired

257 people working in the prime minister’s office were sacked

Turkey’s media regulation body on Tuesday also revoked the licences of 24 radio and TV channels accused of links to Mr Gulen.

The news came on top of the arrests of more than 6,000 military personal and the sackings of nearly 9,000 police officers. About 3,000 judges have also been suspended.

The man is clearly using this opportunity to thoroughly and completely Islamize his country and turn it into a one-party dictatorship. He is also threatening to bring back the death penalty so he can use it against alleged traitors.

I wonder if all the democrats who took to the streets to protest the coup and support Erdogan are rethinking things.

Trump’s Deserved Moment of Triumph

This is one of the two major political parties in the most powerful nation in the world. Don’t laugh. It’s not funny.

— Ross Douthat (@DouthatNYT) July 20, 2016

I get this. I really do. It’s mostly how I feel, though the one consolation I take from this debacle is that genuine creativity may emerge out of Trump’s destruction of the old GOP. It’s a small bit of comfort, but I’ll take what I can. If Marco Rubio or any other of the GOP bunch were being nominated now, I would not be excited at all, or even interested. I prefer that to being freaked out by the prospect of a Trump presidency, but I would prefer to have someone to vote for, instead of against.

But then, I’ve wanted that for years.

Because I’m feeling contrarian, I want to give Donald Trump his due in this, his hour of triumph. He pulled off something that nobody imagined he would do. I remember watching him give a political speech for the first time — my first time watching him, I mean. He was addressing a big crowd in Mobile. I watched the thing nearly gape-mouthed. I could not believe the crudeness, the chaos, and the idiocy of the speech. This won’t go anywhere, I thought, but it’s going to be fun watching him implode.

I laughed a lot at Donald Trump back then. Who’s laughing now?

Here’s Tim Stanley, writing from Cleveland for The Telegraph. Excerpt:

A year ago, Trump was a joke. A media circus. A novelty. We assumed – I assumed – he was in it for the giggles. I thought he’d drop out like he’d down twice before. I thought his total lack of experience, his profanity and his recklessness would count against him in a primary among conservatives. But the very nature of conservatism has changed.

It was likely the rise of Sarah Palin in 2008 that made this possible – a candidate who suggested there was a choice to be made between intellectualism and common sense, and who inspired deep devotion among those who identified with her. Folks don’t identify with Trump in the same, personal way as they did with the hockey mom from Alaska. How can they? He flies everywhere in a private jet and has a model as a wife. But his issues did strike a chord. The Wall cut through.

Trump didn’t just defy the establishment. He defied what we thought for years were the outsiders: the ideological conservatives who hitherto cast themselves as the rebels. By beating Ted Cruz, Trump actually ran an insurgency against the insurgent. He demonstrated that what people wanted wasn’t something more ideologically pure – as Cruz assumed – but something that was totally different.

That is one big positive we can take from this campaign. If Trump can win when challenging the Republican position on trade and war, maybe someone in the future can win while challenging their positions on other things.

Yes, this.

Donald Trump did, in fact, beat the hell out of the GOP Establishment. But let’s also note here that the GOP Establishment beat itself. If you haven’t yet, check out conservative writer Matthew Sheffield’s evisceration of the Republican Industrial Complex. It was e-mailed to me by a Republican friend who until fairly recently was part of that world, and knows about it intimately.

This is also a good time to return to Tucker Carlson’s great Politico piece from January, talking about how the failure of the Republican Industrial Complex created the opening for Trump. Key excerpt:

American presidential elections usually amount to a series of overcorrections: Clinton begat Bush, who produced Obama, whose lax border policies fueled the rise of Trump. In the case of Trump, though, the GOP shares the blame, and not just because his fellow Republicans misdirected their ad buys or waited so long to criticize him. Trump is in part a reaction to the intellectual corruption of the Republican Party. That ought to be obvious to his critics, yet somehow it isn’t.

Consider the conservative nonprofit establishment, which seems to employ most right-of-center adults in Washington. Over the past 40 years, how much donated money have all those think tanks and foundations consumed? Billions, certainly. (Someone better at math and less prone to melancholy should probably figure out the precise number.) Has America become more conservative over that same period? Come on. Most of that cash went to self-perpetuation: Salaries, bonuses, retirement funds, medical, dental, lunches, car services, leases on high-end office space, retreats in Mexico, more fundraising. Unless you were the direct beneficiary of any of that, you’d have to consider it wasted.

Pretty embarrassing. And yet they’re not embarrassed. Many of those same overpaid, underperforming tax-exempt sinecure-holders are now demanding that Trump be stopped. Why? Because, as his critics have noted in a rising chorus of hysteria, Trump represents “an existential threat to conservatism.”

Let that sink in. Conservative voters are being scolded for supporting a candidate they consider conservative because it would be bad for conservatism? And by the way, the people doing the scolding? They’re the ones who’ve been advocating for open borders, and nation-building in countries whose populations hate us, and trade deals that eliminated jobs while enriching their donors, all while implicitly mocking the base for its worries about abortion and gay marriage and the pace of demographic change. Now they’re telling their voters to shut up and obey, and if they don’t, they’re liberal.

It turns out the GOP wasn’t simply out of touch with its voters; the party had no idea who its voters were or what they believed. For decades, party leaders and intellectuals imagined that most Republicans were broadly libertarian on economics and basically neoconservative on foreign policy. That may sound absurd now, after Trump has attacked nearly the entire Republican catechism (he savaged the Iraq War and hedge fund managers in the same debate) and been greatly rewarded for it, but that was the assumption the GOP brain trust operated under. They had no way of knowing otherwise. The only Republicans they talked to read the Wall Street Journal too.

On immigration policy, party elders were caught completely by surprise. Even canny operators like Ted Cruz didn’t appreciate the depth of voter anger on the subject. And why would they? If you live in an affluent ZIP code, it’s hard to see a downside to mass low-wage immigration. Your kids don’t go to public school. You don’t take the bus or use the emergency room for health care. No immigrant is competing for your job. (The day Hondurans start getting hired as green energy lobbyists is the day my neighbors become nativists.) Plus, you get cheap servants, and get to feel welcoming and virtuous while paying them less per hour than your kids make at a summer job on Nantucket. It’s all good.

Apart from his line about Mexican rapists early in the campaign, Trump hasn’t said anything especially shocking about immigration. Control the border, deport lawbreakers, try not to admit violent criminals — these are the ravings of a Nazi? This is the “ghost of George Wallace” that a Politico piece described last August? A lot of Republican leaders think so. No wonder their voters are rebelling.

Read the whole thing. Let it sink in that Carlson wrote this before a single vote had been cast in the GOP primaries.

This year, and this week, in Republican Party politics and in American conservatism has been about nothing but moral, intellectual, and institutional decadence. It did not happen because of Donald Trump. Donald Trump emerged because the institutions were rotten. It is an almost Shakespearean twist that Roger Ailes is being defenestrated from atop the Fox News empire even as Trump receives his crown in Cleveland.

Trump didn’t steal the Republican Party. It was his for the taking, because the people who run it and the institutions surrounding it failed.

When Trump loses in November, maybe, just maybe, some new blood and new ideas will rebuild the party.

And if he wins? We will have far bigger things to worry about than the fate of the Republican Party. We will be forced to contemplate the fate of the Republic itself.

Trump’s Deserved Moment Of Triumph

This is one of the two major political parties in the most powerful nation in the world. Don't laugh. It's not funny.

— Ross Douthat (@DouthatNYT) July 20, 2016

I get this. I really do. It’s mostly how I feel, though the one consolation I take from this debacle is that genuine creativity may emerge out of Trump’s destruction of the old GOP. It’s a small bit of comfort, but I’ll take what I can. If Marco Rubio or any other of the GOP bunch were being nominated now, I would not be excited at all, or even interested. I prefer that to being freaked out by the prospect of a Trump presidency, but I would prefer to have someone to vote for, instead of against.

But then, I’ve wanted that for years.

Because I’m feeling contrarian, I want to give Donald Trump his due in this, his hour of triumph. He pulled off something that nobody imagined he would do. I remember watching him give a political speech for the first time — my first time watching him, I mean. He was addressing a big crowd in Mobile. I watched the thing nearly gape-mouthed. I could not believe the crudeness, the chaos, and the idiocy of the speech. This won’t go anywhere, I thought, but it’s going to be fun watching him implode.

I laughed a lot at Donald Trump back then. Who’s laughing now?

Here’s Tim Stanley, writing from Cleveland for The Telegraph. Excerpt:

A year ago, Trump was a joke. A media circus. A novelty. We assumed – I assumed – he was in it for the giggles. I thought he’d drop out like he’d down twice before. I thought his total lack of experience, his profanity and his recklessness would count against him in a primary among conservatives. But the very nature of conservatism has changed.

It was likely the rise of Sarah Palin in 2008 that made this possible – a candidate who suggested there was a choice to be made between intellectualism and common sense, and who inspired deep devotion among those who identified with her. Folks don’t identify with Trump in the same, personal way as they did with the hockey mom from Alaska. How can they? He flies everywhere in a private jet and has a model as a wife. But his issues did strike a chord. The Wall cut through.

Trump didn’t just defy the establishment. He defied what we thought for years were the outsiders: the ideological conservatives who hitherto cast themselves as the rebels. By beating Ted Cruz, Trump actually ran an insurgency against the insurgent. He demonstrated that what people wanted wasn’t something more ideologically pure – as Cruz assumed – but something that was totally different.

That is one big positive we can take from this campaign. If Trump can win when challenging the Republican position on trade and war, maybe someone in the future can win while challenging their positions on other things.

Yes, this.

Donald Trump did, in fact, beat the hell out of the GOP Establishment. But let’s also note here that the GOP Establishment beat itself. If you haven’t yet, check out conservative writer Matthew Sheffield’s evisceration of the Republican Industrial Complex. It was e-mailed to me by a Republican friend who until fairly recently was part of that world, and knows about it intimately.

This is also a good time to return to Tucker Carlson’s great Politico piece from January, talking about how the failure of the Republican Industrial Complex created the opening for Trump. Key excerpt:

American presidential elections usually amount to a series of overcorrections: Clinton begat Bush, who produced Obama, whose lax border policies fueled the rise of Trump. In the case of Trump, though, the GOP shares the blame, and not just because his fellow Republicans misdirected their ad buys or waited so long to criticize him. Trump is in part a reaction to the intellectual corruption of the Republican Party. That ought to be obvious to his critics, yet somehow it isn’t.

Consider the conservative nonprofit establishment, which seems to employ most right-of-center adults in Washington. Over the past 40 years, how much donated money have all those think tanks and foundations consumed? Billions, certainly. (Someone better at math and less prone to melancholy should probably figure out the precise number.) Has America become more conservative over that same period? Come on. Most of that cash went to self-perpetuation: Salaries, bonuses, retirement funds, medical, dental, lunches, car services, leases on high-end office space, retreats in Mexico, more fundraising. Unless you were the direct beneficiary of any of that, you’d have to consider it wasted.

Pretty embarrassing. And yet they’re not embarrassed. Many of those same overpaid, underperforming tax-exempt sinecure-holders are now demanding that Trump be stopped. Why? Because, as his critics have noted in a rising chorus of hysteria, Trump represents “an existential threat to conservatism.”

Let that sink in. Conservative voters are being scolded for supporting a candidate they consider conservative because it would be bad for conservatism? And by the way, the people doing the scolding? They’re the ones who’ve been advocating for open borders, and nation-building in countries whose populations hate us, and trade deals that eliminated jobs while enriching their donors, all while implicitly mocking the base for its worries about abortion and gay marriage and the pace of demographic change. Now they’re telling their voters to shut up and obey, and if they don’t, they’re liberal.

It turns out the GOP wasn’t simply out of touch with its voters; the party had no idea who its voters were or what they believed. For decades, party leaders and intellectuals imagined that most Republicans were broadly libertarian on economics and basically neoconservative on foreign policy. That may sound absurd now, after Trump has attacked nearly the entire Republican catechism (he savaged the Iraq War and hedge fund managers in the same debate) and been greatly rewarded for it, but that was the assumption the GOP brain trust operated under. They had no way of knowing otherwise. The only Republicans they talked to read the Wall Street Journal too.

On immigration policy, party elders were caught completely by surprise. Even canny operators like Ted Cruz didn’t appreciate the depth of voter anger on the subject. And why would they? If you live in an affluent ZIP code, it’s hard to see a downside to mass low-wage immigration. Your kids don’t go to public school. You don’t take the bus or use the emergency room for health care. No immigrant is competing for your job. (The day Hondurans start getting hired as green energy lobbyists is the day my neighbors become nativists.) Plus, you get cheap servants, and get to feel welcoming and virtuous while paying them less per hour than your kids make at a summer job on Nantucket. It’s all good.

Apart from his line about Mexican rapists early in the campaign, Trump hasn’t said anything especially shocking about immigration. Control the border, deport lawbreakers, try not to admit violent criminals — these are the ravings of a Nazi? This is the “ghost of George Wallace” that a Politico piece described last August? A lot of Republican leaders think so. No wonder their voters are rebelling.

Read the whole thing. Let it sink in that Carlson wrote this before a single vote had been cast in the GOP primaries.

This year, and this week, in Republican Party politics and in American conservatism has been about nothing but moral, intellectual, and institutional decadence. It did not happen because of Donald Trump. Donald Trump emerged because the institutions were rotten. It is an almost Shakespearean twist that Roger Ailes is being defenestrated from atop the Fox News empire even as Trump receives his crown in Cleveland.

Trump didn’t steal the Republican Party. It was his for the taking, because the people who run it and the institutions surrounding it failed.

When Trump loses in November, maybe, just maybe, some new blood and new ideas will rebuild the party.

And if he wins? We will have far bigger things to worry about than the fate of the Republican Party. We will be forced to contemplate the fate of the Republic itself.

July 19, 2016

Trumps Trip Up Selves With Speeches

So now we know why Melania Trump’s speech was not only lame, but plagiarized in part:

Matthew Scully and John McConnell, who had worked together as speechwriters during Mr. Bush’s first term, wrote a draft of Ms. Trump’s speech in June, sending it to the campaign for review about a month ago.

The pair did not hear back from the campaign until about 10 days ago, according to one person familiar with the conversation, when they were told that the lineup of speeches and the timing of Ms. Trump’s speech had been changed, leading to the speech having to be shortened. Ms. Trump then worked with a person from within the Trump organization to make substantial revisions.

The speech-writing duo was not aware that the speech had been significantly changed until Ms. Trump delivered it on Monday night. According to one source, the only parts that remained from the original draft were the introduction and a passage that included the phrase “a national campaign like no other.”

On the one hand, who cares? She’s a supermodel. One’s oratorical expectations are not high for that sort of person. On the other hand, now that we know more about how this debacle happened, this symbolizes something problematic about the Trump operation. It hired two of the best speechwriters in the business to craft that address, then threw out their work at virtually the last minute to handle it in house. Because Trump knows better, probably. And they ended up humiliating Melania Trump with their corner-cutting and lack of integrity.

A small thing? Yeah, mostly. But if it reveals a mindset within the Trump campaign, a sense that they know better than others, this could be a real problem for a Trump presidency. Then again, it must be admitted that all the GOP campaign experts couldn’t defeat an amateur like Donald Trump this past year. Nor did having a bunch of serious experts advising George W. Bush prevent him from leading the country into a disastrous war. Nevertheless, this was a very easy error to have avoided, and the fact that Donald Trump hasn’t made a public example of someone for having caused his wife to make a fool of herself in public probably indicates that somebody else in the family made the fatal call.

UPDATE: Holy Scott McConnell’s Great Aunt Agatha, Donald Jr. just plagiarized TAC in his convention speech!:

This family is either truly crazy, or they’re trolling us like bosses.

UPDATE.2: Ah, but the plot thickens. This is Frank Buckley, author of the TAC article, and a Trump fan:

Except it wasn't stealing…

— Frank Buckley (@fbuckley) July 20, 2016

He probably wrote the speech for Trump fils. Is it plagiarism if you quote yourself? To be clear, even though Buckley’s essay appeared in TAC, I have no idea if he had anything to do with writing Trump Jr.’s speech. We’ll have to hear from him on it.

UPDATE.3: Aaaaand, that’s a wrap:

F.H. Buckley tells @businessinsider: "I was a speechwriter for this speech. So I'm afraid there's no issue here."

— Brett LoGiurato (@BrettLoGiurato) July 20, 2016

Alleged Perv Roger Ailes Out

Fox News confirmed to The Daily Beast editor-at-large Lloyd Grove on Tuesday that beleagured chairman and CEO Roger Ailes will depart the cable news network following sexual harassment claims by former anchor Gretchen Carlson. According to a document obtained by the Drudge Report, Ailes will receive at least a $40 million buyout from the network. The news comes hours after New York Magazine reporter Gabe Sherman wrote that Fox News star Megyn Kelly told investigators hired by 21st Century Fox that Ailes had sexually harassed her ten years ago.

Let’s stop and think about this: $40 million to buy this guy out? I suppose the Murdochs believe it will cut their losses in the end, but still. $40 million to make Roger Ailes go away.

There has been no trial and no admission of guilt on Ailes’s part, so we can’t say if the allegations of sexual harassment are true. If they are, though, I hope they all come out now that Ailes is not in a position to hurt anybody’s career at Fox.

Here’s a great tweetstorm from the other day about sexual harassment within Conservatism, Inc.:

I have no idea if @GretchenCarlson is telling the truth, only two people on Earth know for certain if she is. BUT. 1/

— Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

I do know there is a serious problem with sexual harassment in the conservative movement. Most women in it have war stories. 2/ — Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

When I was *first* starting out, I had a mentoring meeting w/ an older man in his office. I was naive. He was socially conservative. 3/

— Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

He spent most of meeting telling me that I would get much farther in my career if I was sexually unattached. (I was dating @SethAMandel) 4/ — Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

I never had an issue at Heritage or Commentary (or since), but that is due to the fact that my bosses were highly ethical and decent. 5/

— Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

I also chose wisely who I met with and potentially worked for after that incident. I no longer was willing to work for just anyone. 6/ — Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

The most infuriating part is how pervasive it is with social conservatives, this treating women like pieces of meat thing. 7/

— Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

We talk about honoring women, but oh the things that are said behind closed doors. Someone will write a book about it one day. 8/ — Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

Which is why it’s so important to have women mentors in this movement, and for women to be honest with one another about dangerous men. 9/

— Bethany S. Mandel (@bethanyshondark) July 13, 2016

Preach it, sister. I hope somebody does write that book. And if Ailes is guilty, I hope that Gretchen Carlson gets a good chunk of that $40 million pile.

As little as I like what feminism has become, I am enthusiastically grateful that it has brought about a world in which powerful men have to worry that they could lose everything for mistreating women this way. Clearly not enough of them do. Yet.

This Tired White People Business

I am reluctant to defend Rep. Steve King, the Iowa Republican, who stepped in it yesterday on MSNBC. But I do want to make a point about the dust-up. Here’s what happened:

If you don’t have time to watch it, the clip starts with Charles Pierce, a grey-bearded white liberal, saying that the “optimistic” view is that “this is the last time that old white people” will command the GOP. He continues:

Tell you what, in that hall today, that hall is wired. That hall is wired by loud, unhappy, dissatisfied white people. Any sign of rebellion is going to get shouted down either kindly or roughly but that’s what’s going to happen.

To which King responds:

This whole white people business does get a little tired, Charlie. I would ask you to go back through history and figure out where are these contributions that have been made by these other categories of people you are talking about. Where did any other subgroup of people contribute more to civilization?

Host Chris Hayes asks incredulously, “Than white people?”

“Than Western civilization itself,” says King. “That’s rooted in western Europe, eastern Europe and the United States of America, and every place where Christianity settled the world. That’s all of Western civilization.”

Horrors, etc.

King answered that poorly, but I’ll sympathize with him on this point: this “whole white people business” carried on by liberals like Charlie Pierce really does get tired. Let me explain.

First, the fact that the GOP, especially under Trump, is doubling down on its identity as a party only of white people is a perfectly legitimate political point to discuss. Steve King ought to have been prepared to discuss this instead of launching into a weird tangent about the comparative cultural contributions of white people to Western civilization.

(Side note: isn’t “Western civilization” — the civilization that emerged in Europe from the intellectual and cultural confluence of Athens, Rome, and Jerusalem — by definition almost wholly a matter of the contribution of Germanic, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew people we now consider to be “white”? Isn’t this a silly debate? Does anybody really believe that Europeans made a significant contribution to Chinese civilization, or African civilization, or Indian civilization, and so forth? Who cares?)

But I understand why King went there. It is deeply annoying how often liberals deploy “old white male” as a term of abuse. Let’s say that this has been a panel on the Fox News Channel covering the Democratic convention, and some right-of-center writer criticized a Black Lives Matter moment at the event as being “wired by loud, unhappy, dissatisfied black people.” How well do you think that would have gone over, even if it was true? I think Pierce’s observation was, in fact, true, but the context in which he made it is the believe that there is obviously something bad about white people being angry, or in any way being conscious of and defending what they perceive to be their interests. This is a double standard that nobody on the left applies to black people, Hispanic people, gay people, feminists, or anybody else on their side.

The discourse on the left, in fact, has become so saturated with the concept of “old white males” as hate figures that I don’t think many liberals understand that they do it, and why it is offensive. In point of fact, everyone who enjoys the fruits of Western civilization owes a lot to old white males. Everyone who enjoys benefits bequeathed to us by African culture owes a lot to old black males, and so on. It’s a stupid, anti-intellectual argument, one that’s the mirror image of the stupid, anti-intellectual argument that says only whites, or white men, have anything worth saying or contributing.

If I had been writing Steve King’s response, here’s what I would have said:

This whole white people business does get a little tired, Charlie. It gets really tiresome, hearing people like you spout off about white people, as if the color of our skin was some sort of moral fault. If you really feel that way, why aren’t you, as an old white guy, not giving up your chair here on the MSNBC set to a young black woman? I presume that’s because you believe that you have valuable things to say about politics. So quit racializing things, and stop talking like there’s something wrong with white people acting in what they perceive to be their own interests. You don’t talk about any other racial or demographic group that way. Liberals don’t go on TV to complain about ‘angry black people’ — and if a conservative did, you’d all scream bloody murder about what racists we are. Why the double standard?

Look, Charlie, it’s fair to ask why the Republican Party attracts so few racial minorities, and how we plan to deal with that as the country gets less white. But let me turn this around. Why does the Democratic Party repel so many white working class people? Why do the Democrats alienate religious conservatives? It wasn’t always this way. You have become the party of racial minorities and educated white elites. If minorities and white elites see their interests better represented by the Democrats, then I don’t blame them for being Democrats. But why don’t you worry about why so many of your fellow Americans feel excluded by the Democratic Party? Why is this not a concern to you? Maybe it’s because they know that liberals like you look down on people like them, and consider them the enemy. And you know what, Charlie? They’re right.

Scientists Make Terrible Politicians

To make a political decision, you sort through the evidence to find the facts that are most relevant to the issue—and “relevant,” please note, is a value judgement, not a simple matter of fact. Using the relevant evidence as a framework, you weigh competing values against one another—this also involves a value judgment—and then you weigh competing interests against one another, and look for a compromise on which most of the contending parties can more or less agree. If no such compromise can be found, in a democratic society, you put it to a vote and do what the majority says. That’s how politics is done; we might even call it the political method.

That’s not how science is done, though. The scientific method is a way of finding out which statements about nature are false and discarding them, under the not unreasonable assumption that you’ll be left with a set of statements about nature that are as close as possible to the truth. That process rules out compromise. If you’re Lavoisier and you’re trying to figure out how combustion works, you don’t say, hey, here’s the oxygenation theory and there’s the phlogiston theory, let’s agree that half of combustion happens one way and the other half the other; you work out an experiment that will disprove one of them, and accept its verdict. What’s inadmissible in science, though, is the heart of competent politics.

More:

In science, furthermore, interests are entirely irrelevant in theory. (In practice—well, we’ll get to that in a bit.) Decisions about values are transferred from the individual scientist to the scientific community via such practices as peer review, which make and enforce value judgments about what counts as good, relevant, and important research in each field. The point of these habits is to give scientists as much room as possible to focus purely on the evidence, so that facts can be known as facts, without interference from values or interests. It’s precisely the habits of mind that exclude values and interests from questions of fact in scientific research that make modern science one of the great intellectual achievements of human history, on a par with the invention of logic by the ancient Greeks.

One of the great intellectual crises of the ancient world, in turn, was the discovery that logic was not the solution to every human problem. A similar crisis hangs over the modern world, as claims that science can solve all human problems prove increasingly hard to defend, and the shrill insistence by figures such as Tyson that it just ain’t so should be read as evidence for the imminence of real trouble. Tyson himself has demonstrated clearly enough that a first-rate grasp of astronomy does not prevent the kind of elementary mistake that gets you an F in Political Science 101. He’s hardly alone in displaying the limits of a scientific education; Richard Dawkins is a thoroughly brilliant biologist, but whenever he opens his mouth about religion, he makes the kind of crass generalizations and jawdropping non sequiturs that college sophomores used to find embarrassingly crude.

None of this is helped by the habit, increasingly common in the scientific community, of demanding that questions having to do with values and interests should be decided, not on the evidence, but purely on the social prestige of science.

Read the whole thing. I hope you do, because Greer discusses the insistence by scientists that Greenpeace are a bunch of idiots for opposing the testing and sale of GMO rice. In fact, Greer points out, the claim that science proves GMO rice is fine conceals serious questions having to do with whether or not it is wise to allow a multinational corporation have control, via patent law, of the major food source for many of the world’s poor. This is not a question that science alone can answer, but by insisting that theirs is the only valid perspective, scientists wrongly dismiss an important dimension of the problem.

But this is the difference between science and Scientism. Scientism is the ideologically charged fallacious belief that science is the only legitimate way of knowledge. Greer leads his essay off by a typically arrogant, typically ill-informed political remark by Neil deGrasse Tyson. Along those lines, here’s science writer Thomas Burnett:

Scientism today is alive and well, as evidenced by the statements of our celebrity scientists:

“The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be.” –Carl Sagan, Cosmos

“The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.” –Stephen Weinberg, The First Three Minutes

“We can be proud as a species because, having discovered that we are alone, we owe the gods very little.” –E.O. Wilson, Consilience

While these men are certainly entitled to their personal opinions and the freedom to express them, the fact that they make such bold claims in their popular science literature blurs the line between solid, evidence-based science, and rampant philosophical speculation. Whether one agrees with the sentiments of these scientists or not, the result of these public pronouncements has served to alienate a large segment of American society. And that is a serious problem, since scientific research relies heavily upon public support for its funding, and environmental policy is shaped by lawmakers who listen to their constituents. From a purely pragmatic standpoint, it would be wise to try a different approach.

Physicist Ian Hutchinson offers an insightful metaphor for the current controversies over science:

“The health of science is in fact jeopardized by scientism, not promoted by it. At the very least, scientism provokes a defensive, immunological, aggressive response from other intellectual communities, in return for its own arrogance and intellectual bullyism. It taints science itself by association.”

I like this comment from one of Greer’s readers:

I work in computers, and there’s a huge tendency among the people I work with to, in the words of someone I can’t remember, see the law and politics as a Universal Turing Machine. That is, they believe that people and the law work just like computer programs and that if they can come up with a clever reading of the law they’ve found a bug they can exploit, even though an actual lawyer would roll their eyes and explain patiently that no, common law doesn’t work that way, intent etc. This mindset then leads into a lot of the more whacky stuff coming out from various libertarian types, who don’t seem to realize that they are making exactly the same mistaken assumptions that the communists did in the 1930s, that we can just engineer away human nature. This will have exactly the same results in the very unlikely event any of their suggestions ever actually happen in practice.

By the way, if you ever want to make a Bay-Area resident change the subject, point out that the current Bay-Area economy looks exactly like Detroit’s did circa 1955 or so.

The problem is that real life, like religion (in the view of H.L. Mencken), is a poem, not a syllogism. This is a truth that smart people often fail to grasp.

July 18, 2016

‘Hail, Cae$ar!’ Preacher Prays

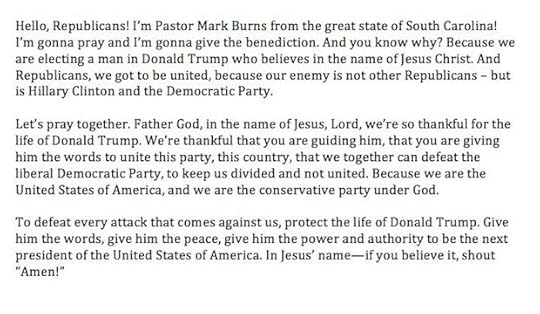

If you don’t have time to watch the short video above, this, via @sullivanamy, is the transcript of the Rev. Mark Burns’ benediction at Monday’s GOP convention:

Mark Burns proclaims the sham teaching called the “prosperity gospel”:

At a March Trump rally in Illinois, Burns leapt up to the stage, pumping up the crowd in chants of Trump’s name. “Lord, this will be the greatest Tuesday that ever existed, come Super Tuesday Three,” he prophesied in prayer, naming and claiming a Trump victory. He opened his eyes. “There is no black person, there is no white person, there is no yellow person, there is no red person, there’s only green people!” he shouted. “Green is money! Green are jobs!!”

Until Trump plucked Burns out of the tiny town of Easley, S.C., few Christians knew the black pastor’s name. But it is God, Burns says, who has economically transformed his life—before he found Jesus, he relied on food stamps, lived in section 8 housing, went to jail, and faced a charge of simple assault as part of his self-described “baby mama drama” past. Then last year, Burns decided to transition his ministry to a for-profit televangelism business, so he and his followers could achieve economic success.

“Jesus said, above all things, I pray that you prosper, I pray that you have life more abundantly,” Burns, 36, explained to TIME in an interview, quoting a verse not from the Gospels but another New Testament passage. “It was never Jesus’ intention for us to be broke.” All of this is wisdom is now contained in a candidate for President. “I think that is what Donald Trump represents,” Burns says.

At some point, you just have to stop caring, or you’ll lose your mind.

Cop Killers and Black Lives Matter

Did you see this heated exchange between Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke and CNN’s Don Lemon on the subject of cop killing and Black Lives Matter? Watch:

Meanwhile, The New York Times reports that the police have concluded that Gavin Long lured them into an ambush that resulted in three police deaths. Excerpt:

On a social media site registered under the name Gavin Long, a young African-American man who refers to himself as “Cosmo” posted videos and podcasts and shared biographical and personal information that aligned with the information that the authorities had released, so far, about the gunman.

In one YouTube video, titled “Protesting, Oppression and How to Deal with Bullies,” the man discusses the killings of African-American men at the hands of police officers, including the July 5 death in Baton Rouge of Alton B. Sterling, and he advocates a bloody response instead of the protests that the deaths sparked.

“One hundred percent of revolutions, of victims fighting their oppressors,” he said, “have been successful through fighting back, through bloodshed. Zero have been successful just over simply protesting. It doesn’t — it has never worked and it never will. You got to fight back. That’s the only way that a bully knows to quit.”

“You’ve got to stand on your rights, just like George Washington did, just like the other white rebels they celebrate and salute did,” he added. “That’s what Nat Turner did. That’s what Malcolm did. You got to stand, man. You got to sacrifice.”

Elsewhere, the Times writes:

The twin attacks — three officers dead Sunday in Baton Rouge, five killed on July 7 in Dallas, along with at least 12 injured over all — have set off a period of fear, anguish and confusion among the nation’s 900,000 state and local law enforcement officers. Even the most hardened veterans call this one of the most charged moments of policing they have experienced.

Officers from Seattle to New Orleans are pairing up in squad cars for added safety and keeping their eyes open for snipers while walking posts. It is an anxious time: Officers must handle not only vocal denunciations from peaceful protesters who criticize abusive policing, but also physical attacks by a tiny few on the periphery.

Law enforcement officials said it had been generations since the nation endured two separate episodes in which so many police officers were killed.

“We’ve seen nothing like this at all,” said Darrel W. Stephens, the executive director of the Major Cities Chiefs Association and an instructor at the Public Safety Leadership Program at Johns Hopkins University. “The average officer in America, who was tense anyway, their tension and vigilance is going to increase even more. Police officers have always been vulnerable, and they know it. But somewhere inside you, you didn’t think it would happen. But now we’re seeing it happen.”

According to 2015 police statistics, the overwhelming number of murders and other violent crimes in Baton Rouge, a violent city, happen in the wholly or predominantly black parts of town. It’s not even close. Look at this SpotCrime map of Baton Rouge, which aggregates the most recent crime data and plots the incidents on a map: almost all of these incidents in the past two weeks occurred in predominantly African-American areas. The population of East Baton Rouge Parish, which is the city, is 46 percent black [UPDATE: Inside the boundaries of the city proper, it’s 55 percent black]. Poverty in the parish is concentrated in, yes, the black part of town.

My point is this: if you are a BR police officer or EBRP sheriff’s deputy, you spend a disproportionate amount of your time policing the black community, which is disproportionately violent. By no means is this to say that police brutality is justified or is not a problem. It is to point out that police brutality occurs within the context of a badly broken society. Our society overall asks cops — white, black, Hispanic, and Asian — to go into parts of our cities where most of us would never venture, and deal on a daily basis with some of the worst people in the world: killers, drug dealers, pimps, wife-beaters, etc. Many of these cretins are armed. I’m not sure how someone contends with the worst of humanity as part of one’s job without losing one’s own humanity. I wouldn’t last a day out there on the inner-city beat, and you probably wouldn’t either.

I don’t understand why we are given an either-or. Why can’t we be in favor of reforming the police to reduce brutality and stand by the police, recognizing that the great majority of law enforcement officers are good men and women who try to do the right thing in an extremely difficult job?

As a general rule, I reject people who blame violent acts on their political opponents. More often than not, this is an attempt to silence speech they don’t like. If people have a problem with police brutality or what they see as racist treatment of black people, then by all means they have a right to speak out against it. This is true with any issue. Conservatives who rightly despise the way the campus left tries to silence dissent should be very careful not to do the same thing to those protesting against the police.

That said, with eight police dead this month at the hands of black radicals who deliberately targeted them as a political statement, Black Lives Matter is at a crossroads. This kind of rhetoric, authored by BLM’s founders and taken from its website, drives its followers to radical extremes:

We completely expect those who benefit directly and improperly from White supremacy to try and erase our existence. We fight that every day. … When we say Black Lives Matter, we are talking about the ways in which Black people are deprived of our basic human rights and dignity. It is an acknowledgement Black poverty and genocide is state violence. It is an acknowledgment that 1 million Black people are locked in cages in this country–one half of all people in prisons or jails–is an act of state violence. … And, perhaps more importantly, when Black people cry out in defense of our lives, which are uniquely, systematically, and savagely targeted by the state, we are asking you, our family, to stand with us in affirming Black lives.

That’s just one example. And this:

We are committed to disrupting the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure requirement by supporting each other as extended families and “villages” that collectively care for one another, and especially “our” children to the degree that mothers, parents and children are comfortable.

This, in a time when 72 percent of all African-American babies are born to single mothers, and that fatherlessness is a strong predictor of whether or not a male will be involved with the criminal justice system.

I don’t blame people at all for protesting against police brutality. What I do object to is the hysterical language (e.g., “genocide”) routinely and repeatedly used by the movement to characterize the situation, and to the decontextualization of the problem such that it makes it appear that police mistreatment is the most significant problem threatening the lives of black people in America.

Ofc. Montrell Jackson’s young black son will grow up without a father, and the boy’s mother without her husband, because a radicalized black man shot and killed him on Sunday, and two of his colleagues. I won’t say this is the fault of Black Lives Matter, because I genuinely believe it’s factually and morally wrong to blame them — this, even though I do not now and never have liked that organization, given its radicalism and its bullying tactics.

But I reserve the right to change my mind on that depending on what happens next.

UPDATE: A pro-Black Lives Matter note was found near a Daytona Beach police cruiser firebombed this past weekend. “F–k The Police,” it also said, charmingly.

UPDATE.2: From the law enforcement presser today in Baton Rouge:

“We’ve been questioned about our militarized tactics, This is why, because we are up against a force that is not playing by the rules.”

— Maya Lau (@mayalau) July 18, 2016

The Troll Move That Ate The GOP

Everybody’s talking about this long piece by Buzzfeed’s conservative politics writer McKay Coppins, talking about how a Trump feature he wrote a while back may have baited Donald into running for president just to show up his critics. Excerpts:

Donald Trump stood on a debate stage in downtown Detroit, surrounded by haters he was determined to dispatch: Liddle Marco to his right, Lyin’ Ted to his left, Megyn Kelly at the moderator’s table straight ahead, and — somewhere out there, in a darkened living room 1,500 miles away — me.

About 30 minutes into the debate, Kelly asked Trump to respond to a recent BuzzFeed News report about his position on immigration.

“First of all, BuzzFeed?” Trump said, waving an index finger in the air. “They were the ones that said under no circumstances will I run for president — and were they wrong.” My phone lit up with a frenzied flurry of tweets, texts, and emails, each one carrying variations of the same message: This is all your fault.

It has to do with a 2013 profile Coppins wrote of Trump, claiming that his presidential candidacy was a sham. It badly got on Trump’s nerves, and he wouldn’t stop tweeting about it and complaining about it. Trump became obsessed, publicly so. More:

As Trump completed his conquest of the Republican Party this year, I contemplated my supposed role in the imminent fall of the republic — retracing my steps; poring over old notes, interviews, and biographies; talking to dozens of people. What had most struck me during my two days with Trump was his sad struggle to extract even an ounce of respect from a political establishment that plainly viewed him as a sideshow. But what I didn’t realize at the time was that he’d felt this way for virtually his entire life — face pressed up against the window, longing for an invitation, burning with resentment, plotting his revenge.

I had landed on a long and esteemed list of haters and losers — spanning decades, stretching from Wharton to Wall Street to the Oval Office — who have ridiculed him, rejected him, dismissed him, mocked him, sneered at him, humiliated him — and, now, propelled him all the way to the Republican presidential nomination, with just one hater left standing between him and the nuclear launch codes.

What have we done?

Read the whole thing. You’ll enjoy it, I predict. The thing about it is how, through piling up telling details, Coppins shows that Trump has only ever been about showing up the people who look down on him. For example, here’s Coppins talking about how the White House Correspondents Dinner turned into a roast of Trump, who was in the audience and didn’t expect to become the butt of so many jokes:

The longer the night went on, the more conspicuous Trump’s glower became. He didn’t offer a self-deprecating chuckle, or wave warmly at the cameras, or smile with the practiced good humor of the aristocrats and A-listers who know they must never allow themselves to appear threatened by a joke at their expense. Instead, Trump just sat there, stone-faced, stunned, simmering — Carrie at the prom covered in pig’s blood.

There’s this moment from last year, just before Trump made his presidential announcement, which was still not a sure thing:

One morning in early June, Nunberg recalled, he was sitting in Trump Tower as his boss read that day’s New York Post. There was a column by conservative writer Jonah Goldberg gleefully ridiculing the Apprentice star’s 2016 prospects. “He’s a more plausible candidate than, say, Honey Boo Boo,” it read, “but that’s mostly because of constitutional age limits.” When Trump finished, he set the paper down quietly on his desk.

“Why don’t they respect me, Sam?” Trump asked.

The pathos of these moments is, frankly, stunning. You see that behind all that bullying and bluster is a radically insecure boy from Queens who can’t buy his way into the elites and who doesn’t understand why. Trump naturally appeals to and channels the resentment of people like him. This explains the political jiu-jitsu he’s been doing for the past year, and that has allowed him to defeat the GOP Establishment: the more they make fun of him, the more powerful he becomes.

The last American president who was so radically insecure and resentful was Richard Nixon, who was undone by his paranoia, and very nearly caused a constitutional crisis. Nixon was an extraordinarily gifted politician who, whatever his many faults, understood statesmanship. Trump is just a guy from TV. And he might just become the most powerful man in the world.

Coppins’s piece is one long brief for why a man who is so messed up on the inside should never, ever be given that kind of power. But you know what? He just might win. Voters this year have the chance to choose between the Nixon Of The Democrats, and Donald Milhous Trump, who has all of Nixon’s vices but none of his virtues.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers